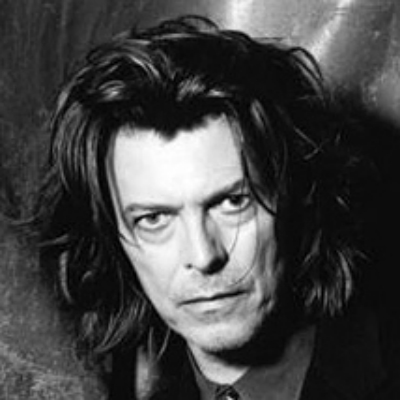

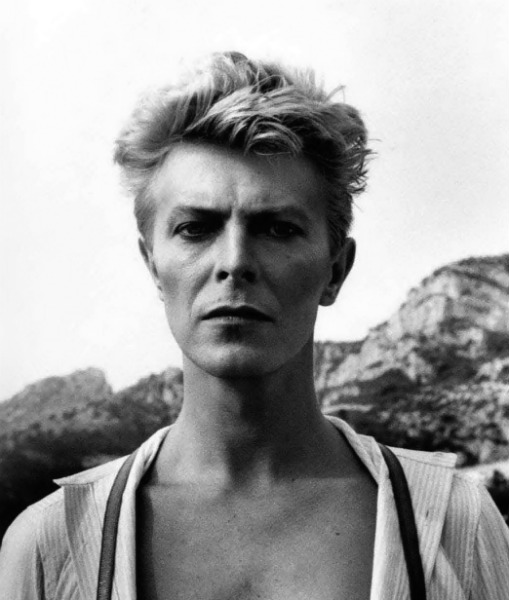

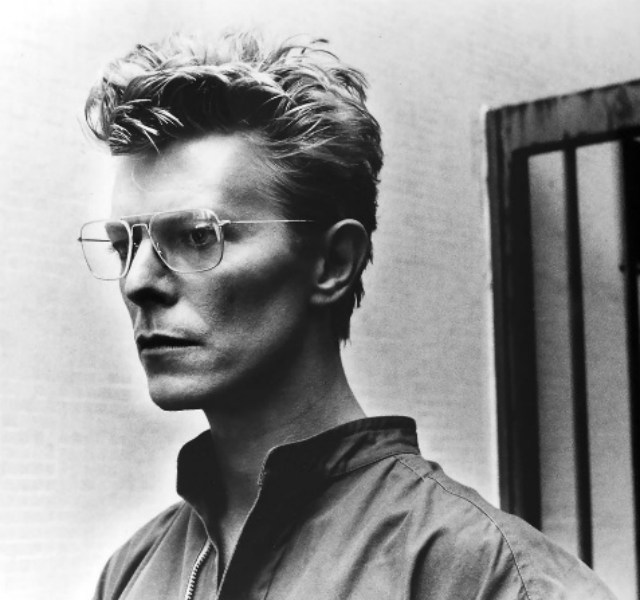

David Bowie (detail) | Photo: Clive Arrowsmith, 1990

Art & Individuality

To undertake a voyage of discovery in pursuit of a vision, to risk one’s skin in the quest for renewal and then, in the end, to deliver a work that sings—only the artist’s individuality triumphing over the collective’s mediocrity can achieve this. In this series I will honour works of art that, through their singularity, testify to the triumph of individuality.

You can listen to the tracks in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

DAVID BOWIE: BLACKSTAR, OR THE ETHICS OF THE ARTIST

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

Sylvia Plath, ‘Lady Lazarus’

David Bowie was never tormented by demons of the kind that plagued Sylvia Plath. On the contrary, the spirits that presided over his destiny belonged to the higher orders of angels (‘I was always the lucky one’, as he put it in an interview with Melody Maker, 29 October 1977). And yet, in his mouth, Sylvia’s lines from ‘Lady Lazarus’ would slip ‘trippingly on the tongue’. Indeed, just as the evidence of organizational culture is how people behave when no-one is watching, so the way we live our death is evidence of the way we have lived our life: It is a sign of our ethics, of the stance we have adopted in the face of what life throws at us.

Ethics, for me, is above all a question of how we position ourselves in relation to risk. Do we prefer the in-crowd to outsiders? Do we seek safety in numbers or are we ready to risk isolation? Do we adopt others’ standards or do we assume our own? On one side, the comfort of conformism at the price of individuality; on the other, individuality at the risk of radical isolation. An over-simplification? Of course. Yet I, for one, in my engagements with others (artists and ordinary people), find it easy to determine their ethics by this touchstone. Now, lest the reader misconstrue my remarks, let me state unequivocally that my notion of ethics in art has nothing to do with the ‘content’ or ‘effects’ of an artwork, but rather with the ‘ethos’ of the artist and his or her relation to their work.

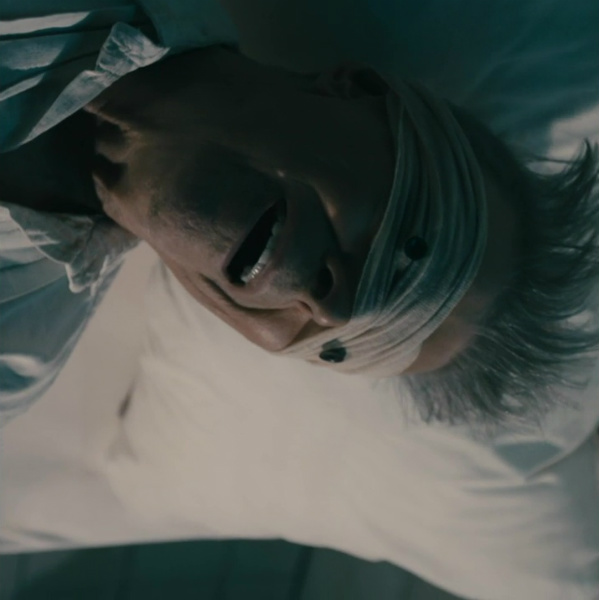

David Bowie | Screenshot from ‘Blackstar’ video

Of all the great rock stars (a role he could never, of course, be reduced to), David Bowie was the one who had the clearest, most consistent and most fully-realized conception of himself as an artist. (Jim Morrison was another for whom ‘rock star’ was strictly secondary to ‘artist’; same goes, but in a register other than ‘rock star’, for Marianne Faithfull and Patti Smith).

Marianne Faithull | Hedi Slimane, 2014

David Bowie | Irving Penn, 1999

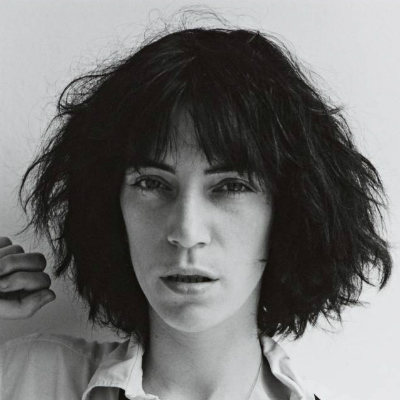

Patti Smith | Robert Mapplethorpe, 1975

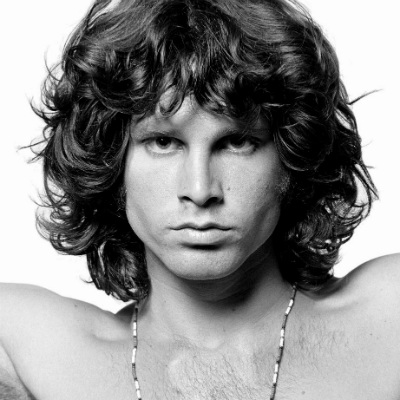

Jim Morrison | Joel Brodsky, 1967

Here are ten ways Bowie articulated this in the 1970s (I could easily cite dozens more for each subsequent decade in which he spoke publicly):

1. I think I’ve always known when to stop doing something. I’ve never been of the opinion that’s it’s necessarily a wise thing to keep on a successful streak if you’re just duplicating all the time. (Melody Maker interview, 14 September 1974)

2. I still haven’t become overground. I’m just the largest-selling of the underground. (Melody Maker interview, 28 February 1976)

3. My role as an artist in rock is rather different to most. I encapsulate things very quickly. And generally my policy has been that as soon as a system or process works, it’s out of date. I move on to another area. Another piece of time. (Melody Maker interview, 29 October 1977)

4. I can’t tolerate people who want to form, or be part of, movements. It should always come back to individuals. (Melody Maker interview, 29 October 1977)

5. I hardly ever listen to anything that’s currently in vogue or popular. (ZigZag interview, January 1978)

6. I was entering an area of middle-of-the-road popularity which I didn’t like, with that disco-soul phase, and it was all getting too successful in the wrong way. I want and need creative, artistic success. I don’t want, need or strive for numbers. I want quality, not a rock and roll career. (Melody Maker interview, 18 February 1978)

7. I’ve got to have the element that surprises me else I’m not on the panic level button, which I’ve got to have to make it live. If it becomes too sheltered and precious, it shows like hell and looks self-satisfied. (Melody Maker interview, 18 February 1978)

8. It’s hard to remain artistically illegitimate; it’s so easy to become legitimate and Establishment. That became a cause: ‘How can I avoid the next?’. I’d hate to become part of the accepted cultural set-up. You know, ‘That’s it, nicely in place’. That’s not what an artist wants to do. (Melody Maker interview, 18 February 1978)

9. The only way to remain a vibrant part of what is happening is to keep working anew all the time. For me it always will be change. I can’t envisage any period of creative stability and resting on any laurels. (Melody Maker interview, 18 February 1978)

10. I have absolutely no interest whatsoever in politics. Never have had, and probably never will. May I live and die an artist! (Melody Maker interview, 18 February 1978)

Till the end, David Bowie was an individual, sovereign in upholding the ethics of art. Today, when the least manifestation of craft is labelled a work of art, when hyperconsumerism relentlessly pushes customized pills of mass conformism, Blackstar reminds us that art is exigent, that its magic spark is necessarily a function of disjunction (unplugging oneself from the Matrix, if you will).

David Bowie | ‘Lazarus’ video, screenshot 1

David Bowie | ‘Lazarus’ video, screenshot 2

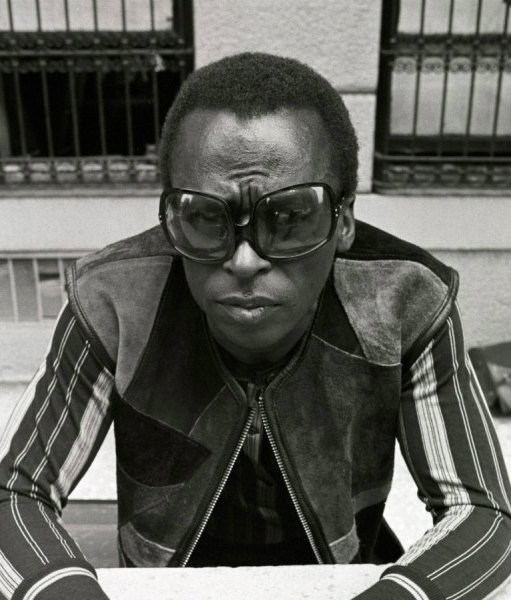

Like Miles Davis, Bowie was a great conceptualist, one whose individuality impelled him to strike out in new directions. Again like Miles, he was a great collaborator, with a knack for drawing out the best from his partners in order to realize his vision. To get a sense of how this worked in the making of Blackstar, one only has to read the commentary on the songs in Nicholas Pegg’s new edition of his book, The Complete David Bowie, where the musicians offer us a wealth of observations on their experience of working with Bowie.

David Bowie | Helmut Newton, 1983

Miles Davis

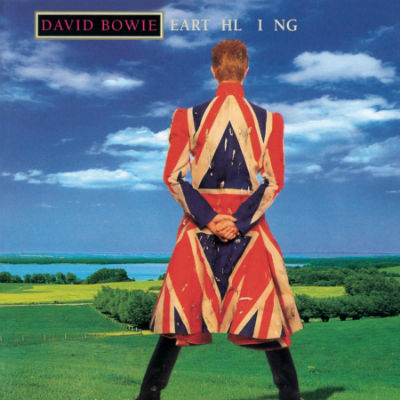

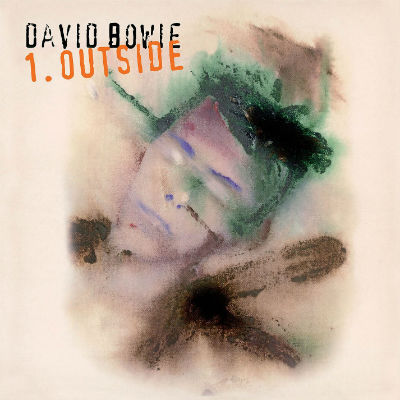

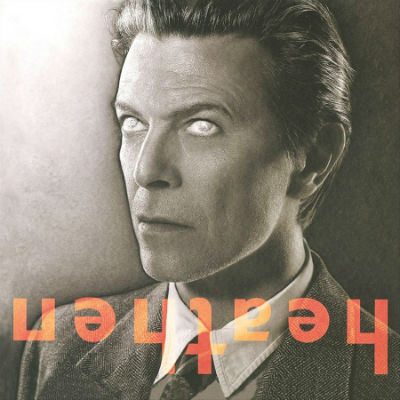

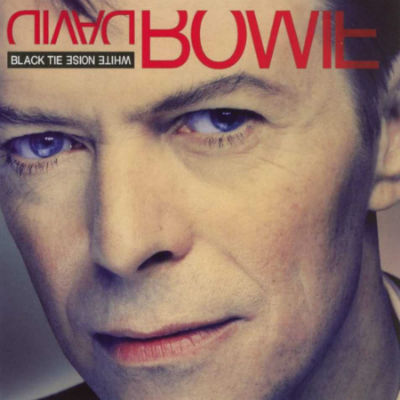

Like all those who suffer fame, much of Bowie’s greatest work is unfamiliar to many in whom his name nevertheless resonates. Heathen, Black Tie White Noise, Earthling, 1. Outside—in offering us a demonstration of the artist’s ethics, album after album offers us a chapter of his adventures in life-lived-creatively. Trusting only in his artistry, faithful to no Muse but his own, in each album (with rare exceptions) Bowie stretches out a tightrope and walks it. The outcome, almost always, is stimulating and vital. Blackstar, then, is but the crowning achievement of an entire oeuvre characterized by an ethics of risk.

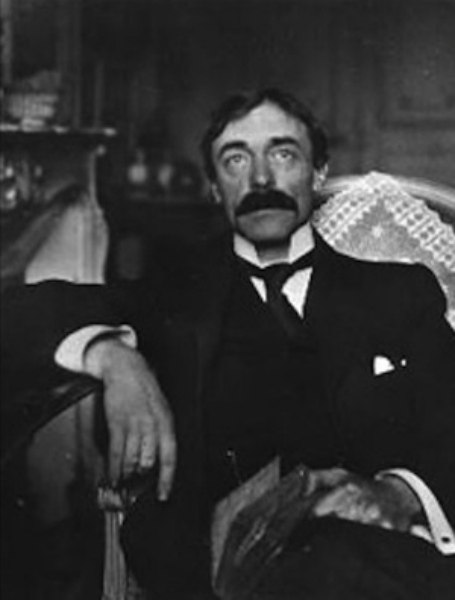

‘My philosophy — It’s in two chapters. These chapters do not follow each other. First one, then the other; or then one and first the other. For in truth they are, and can only be, simultaneous. One is called: Experiences. The other is called: Exercises. I myself am my method.’

Paul Valéry, Cahiers 1 (Paris: Gallimard, ‘Bibliothèque de la Pléiade’, 1973, p. 333 and p. 125 [my translation]).

David Bowie | Clive Arrowsmith, 1990

Paul Valéry

Bowie would have had no hesitation in accepting French poet Paul Valéry’s ‘philosophy’ as a description of his own artistic ethos. Consider the following extracts from his interviews:

1. Aladdin Sane was a result of my paranoia with America at the time. I ran into a very strange type of paranoid person when I was doing Aladdin. Very mixed up people, and I got very upset. It resulted in Aladdin. I knew I didn’t have very much more to say about rock and roll. I mean Ziggy really said as much as I meant to say all along. Aladdin was really Ziggy in America. Again, it was just looking around, seeing what’s in my head. (Melody Maker interview, 14 September 1974)

2. It’s the idea of seeing what you can do with the human persona, how far you can extend the ego out of the body. It’s all very Mcluhanish, isn’t it? I’m trying to make myself the message. (Melody Maker interview, 28 February 1976)

3. Young Americans… I was in a terrible state. I was absolutely infuriated that I was still in rock and roll. (Melody Maker interview, 29 October 1977)

4. [Listening to my albums] I can just about see the year I wrote an album and I can say, ‘Yes, that describes that environment and that year very well’. Which is very good, sort of what I set out to do. (Melody Maker interview, 29 October 1977)

5. Station to Station was like a plea to come back to Europe for me. It was like one of those self-chat things that one has with oneself from time to time. (Melody Maker interview, 29 October 1977)

Jumping from these seventies albums to Blackstar (2016), his final one, we clearly see that Bowie’s artistic ethos is consistent across the decades: In the seventies albums as in Blackstar, he himself is his own ‘method’ (Valéry) or ‘message’ (McLuhan), the life (‘experiences’) and the work (‘exercises’) are intimately entwined. In Blackstar, he enacts, on his own terms, a scenario of his death, just as in all his other albums he enacts, on his own terms, scenarios of his life. This is the honour of the artist, the work conceived as a perpetual becoming; this is the ethics of the artist, the person ever-deepening in individuality (and, be it said in passing, in compassion). ‘May I live and die an artist!’: In life as in death, David Bowie was, above all, an artist.

ALBERT CAMUS ON ART AND ETHICS

Albert Camus

David Bowie, 1982 | Photo: Helmut Newton

Romanticism demonstrates, in fact, that rebellion is part and parcel of dandyism: one of its objectives is appearances. In its conventional forms, dandyism admits a nostalgia for ethics. It is only honour degraded as a point of honour. But at the same time it inaugurates an aesthetic which is still valid in our world, an aesthetic of solitary creators, who are obstinate rivals of a God they condemn. From romanticism onward, the artist’s task will not only be to create a world, or to exalt beauty for its own sake, but also to define an attitude. Thus the artist becomes a model and offers himself as an example: art is his ethic.

Albert Camus, The Rebel: An Essay on Man in Revolt, tr. Anthony Bower (New York: Vintage International, 1991, p. 53)

David Bowie photo credits: Steve Shapiro, 1975; Mick Rock, 1972

‘BLACKSTAR’ – DAVID BOWIE – LYRICS

BLACKSTAR

In the villa of Ormen, in the villa of Ormen

Stands a solitary candle, ah-ah, ah-ah

In the centre of it all, in the centre of it all

Your eyes

On the day of execution, on the day of execution

Only women kneel and smile, ah-ah, ah-ah

At the centre of it all, at the centre of it all

Your eyes, your eyes

Ah-ah-ah… Ah-ah-ah

In the villa of Ormen, in the villa of Ormen

Stands a solitary candle, ah-ah, ah-ah

At the centre of it all, at the centre of it all

Your eyes, your eyes

Ah-ah-ah… Ah-ah-ah

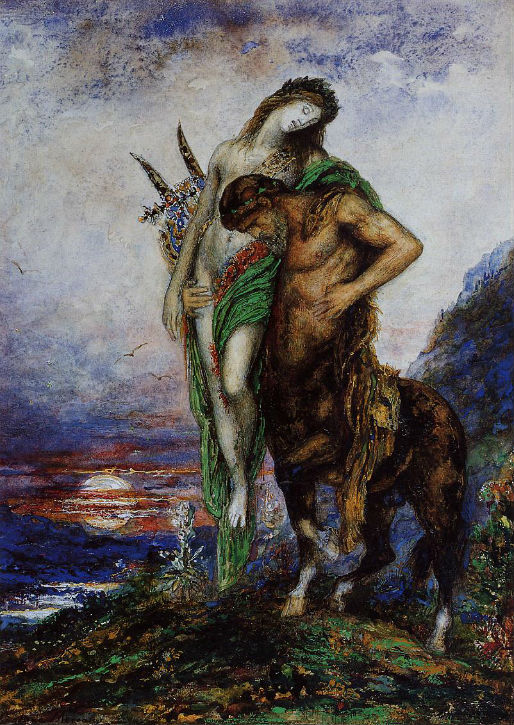

Gustave Moreau, A Dead Poet being Carried by a Centaur, 1890

Gustave Moreau, Fate and the Angel of Death, 1890

Something happened on the day he died

Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside

Somebody else took his place and bravely cried

I’m a black star, I’m a black star

How many times does an angel fall?

How many people lie instead of talking tall?

He trod on sacred ground,

He cried loud into the crowd

I’m a black star, I’m a black star, I’m not a gangster

I can’t answer why—I’m a black star

Just go with me—I’m not a film star

I’m-a take you home—I’m a black star

Take your passport and shoes—I’m not a popstar

And your sedatives, boo—I’m a black star

You’re a flash in the pan—I’m not a Marvel star

I’m the Great I Am—I’m a black star

I’m a black star, way up on money I’ve got game

I see right, so wide, so open-hearted pain

I want eagles in my daydreams, diamonds in my eyes

I’m a black star, I’m a black star

Something happened on the day he died

Spirit rose a metre then stepped aside

Somebody else took his place and bravely cried

I’m a black star, I’m a star’s star, I’m a black star

I can’t answer why—I’m not a gangster

But I can tell you how—I’m not a film star

We were born upside-down—I’m a star’s star

Born the wrong way round—I’m not a white star

I’m a black star, I’m not a gangster

I’m a black star, I’m a black star

I’m not a porn star, I’m not a wandering star

I’m a black star, I’m a black star

In the villa of Ormen

Stands a solitary candle

Ah-ah, ah-ah

At the centre of it all, your eyes

On the day of execution

Only women kneel and smile

Ah-ah, ah-ah

At the centre of it all

Your eyes, your eyes

Ah-ah-ah

Gustave Moreau, The Poet and the Saint, 1868

‘TIS A PITY SHE WAS A WHORE

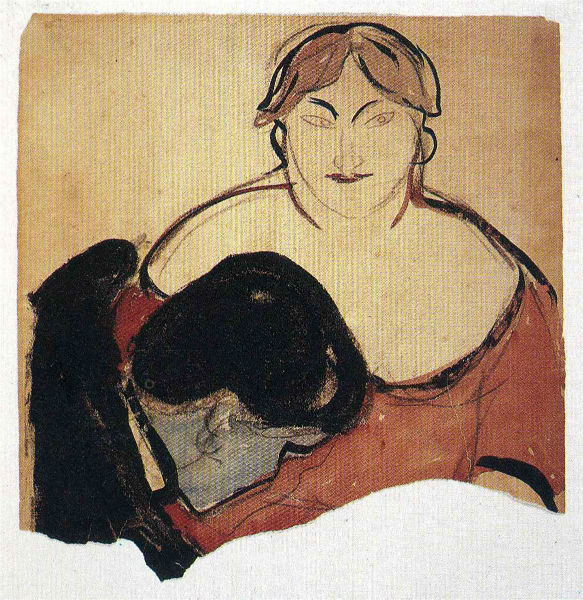

Edvard Munch, Young Man and Prostitute, 1893

Man, she punched me like a dude

Hold your mad hands, I cried

‘Tis a pity she was a whore

‘Tis my curse, I suppose

That was patrol, that was patrol

This is the war

Black struck the kiss, she kept my cock

Smote the mistress, drifting on

‘Tis a pity she was a whore

She stole my purse with rattling speed

That was patrol, this is the war

‘Tis a pity she was a whore

Man, she punched me like a dude

Hold your mad hands, I cried

‘Tis a pity she was a whore

‘Tis my fate, I suppose

For that was patrol, that was patrol

‘Tis a pity she was a whore

LAZARUS

Look up here, I’m in heaven

I’ve got scars that can’t be seen

I’ve got drama, can’t be stolen

Everybody knows me now

Look up here, man, I’m in danger

I’ve got nothing left to lose

I’m so high, it makes my brain whirl

Dropped my cell phone down below

Ain’t that just like me?

By the time I got to New York

I was living like a king

There I used up all my money

I was looking for your ass

This way or no way

You know I’ll be free

Just like that bluebird

Now ain’t that just like me?

Oh, I’ll be free

Just like that bluebird

Oh, I’ll be free

Ain’t that just like me?

Odilon Redon, Poet’s Dream

SUE, OR IN A SEASON OF CRIME

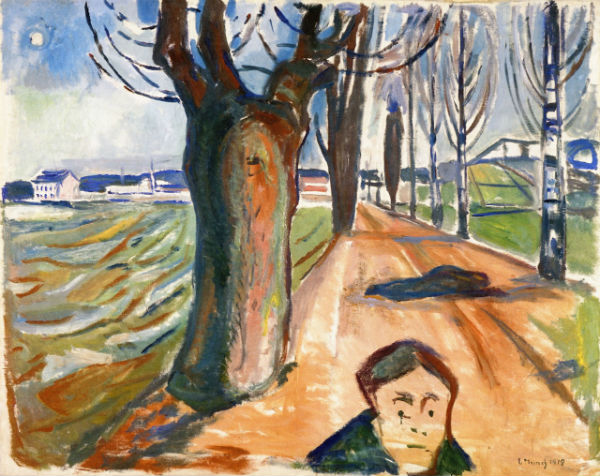

Edvard Munch, Murder on the Road, 1919

Man, she punched me like a dude

Hold your mad hands, I cried

‘Tis a pity she was a whore

‘Tis my curse, I suppose

That was patrol, that was patrol

This is the war

Black struck the kiss, she kept my cock

Smote the mistress, drifting on

‘Tis a pity she was a whore

She stole my purse with rattling speed

That was patrol, this is the war

‘Tis a pity she was a whore

Man, she punched me like a dude

Hold your mad hands, I cried

‘Tis a pity she was a whore

‘Tis my fate, I suppose

For that was patrol, that was patrol

‘Tis a pity she was a whore

GIRL LOVES ME

Cheena so sound, so titi up this malcheck, say

Party up moodge, nanti vellocet round on Tuesday

Real bad dizzy snatch making all the omeys mad — Thursday

Popo blind to the polly in the hole by Friday

Where the fuck did Monday go?

I’m cold to this pig-and-pug show

I’m sittin’ in the chestnut tree

Who the fuck’s gonna mess with me?

Girl loves me—Hey cheena

Girl loves me

Girl loves me—Hey cheena

Girl loves me

Where the fuck did Monday go?

I’m cold to this pig-and-pug show

Where the fuck did Monday go?

You viddy at the cheena

Choodesny with the red rot

Libbilubbing litso-fitso

Devotchka watch her garbles

Spatchko at the rozz-shop

Split a ded from his deng deng

Viddy viddy at the cheena

Girl loves me—Hey cheena

Girl loves me

Girl loves me—Hey cheena

Girl loves me

Girl loves me—Hey cheena

Girl loves me

Where the fuck did Monday go?

Marianne von Werefkin, Girl in Russian Costume, 1888

DOLLAR DAYS

Nils Dardel, The Dying Dandy, 1918

Cash girls suffer me, I’ve got no enemies I’m walking down

It’s nothing to me, it’s nothing to see

If I’ll never see the English evergreens I’m running to

It’s nothing to me, it’s nothing to see

I’m dying to

Push their backs against the grain

And fool them all again and again

I’m trying to

We bitches tear our magazines

Those oligarchs with foaming mouths phone now and then

Don’t believe for just one second I’m forgetting you

I’m trying to, I’m dying to

Dollar days, survival sex

Honour stretching tails to necks I’m falling down

It’s nothing to me, it’s nothing to see

If I’ll never see the English evergreens I’m running to

It’s nothing to me, it’s nothing to see

I’m dying to

Push their backs against the grain

And fool them all again and again

I’m trying to

It’s all gone wrong but on and on

The bitter nerve-ends never end I’m falling down

Don’t believe for just one second I’m forgetting you

I’m trying to, I’m dying to

I CAN’T GIVE EVERYTHING AWAY

I know something’s very wrong

The pulse returns the prodigal sons

The black house hearts, the flowered news

With skull designs upon my shoes

I can’t give everything, I can’t give everything

Away

I can’t give everything away

Seeing more and feeling less

Saying no but meaning yes

This is all I ever meant

That’s the message that I sent

I can’t give everything, I can’t give everything

Away

I can’t give everything away

I know something’s very wrong

The pulse returns the prodigal sons

The black house hearts, the flowered news

With skull designs upon my shoes

I can’t give everything, I can’t give everything

Away

I can’t give everything away

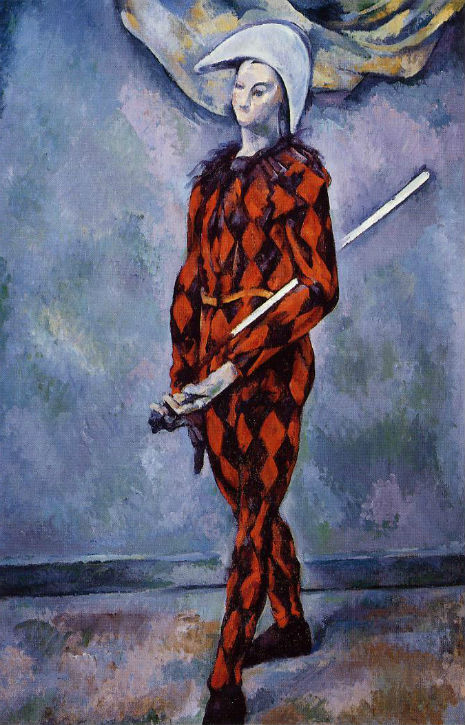

Paul Cézanne, Harlequin, 1890

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2019 | All rights reserved

Comments

2 thoughts on “David Bowie: Blackstar, or the Ethics of the Artist”

A window into the heart and soul of the man and the artist. Hopefully we’ll get another decade of insights.

David Bowie revealed in his own words. Thoughtfully curated by the author, who shines an interesting light on the artist through the lens of ethics. A must read for Bowie fans ready to take the deeper dive.