Ippolita Avalli

‘Simena’

‘Simena’, a work of short fiction by Ippolita Avalli, is made up of a letter and pages from a diary. Below I give the letter in full. More than an epitext and less than a frame-story, it only hints at what’s to come in the diary pages. I leave you, dear visitor, to get your hands on a copy of In the Forbidden City, the anthology in which ‘Simena’ appears, to read the story in full (it’s about 4,600 words in length). Of the story, I will say but this: If Histoire d’O remains the urtext of contemporary erotic writing by women, the palimpsest peering through its interstices, the ‘version’ of it found in ‘Simena’ is far superior to any I’ve read since Pauline Réage’s classic. It pulls off the feat of employing distancing devices yet never diluting the sheer power of its propos.

Tracey Emin, Lonely Chair (drawing II), 2012

‘SIMENA’: THE LETTER THAT OPENS THE STORY

Ippolita Avalli

Rome, October 14, 1996

Dearest Valerio,

Today I received a long missive from Alessia. Pages from a diary—dated August 12—that she wrote on Simena, apparently a few days prior to the awful deed. The letter only arrived today because the zip code was incorrect. The postmark from Istanbul is from a month ago. This means that it wandered from post office to post office before finally finding its way to me. I don’t understand how Alessia could have forgotten my zip code. She knew it by heart. She was obsessive about memorizing numbers. The only way I can explain it to myself is by thinking that she must have done it on purpose, so that the letter would arrive much later. You see, Valerio, it is clear, however difficult to accept: Alessia had designed the entire thing in its most minute details. She was the one who provoked our separation on the island. The argument was a pretext so that she would be left alone. I don’t feel guilty for not having searched for her. There was no way I could have imagined what she had in mind. I didn’t even know that she kept a diary. In the few days that we were together I never saw her writing. I didn’t find paper in her suitcase, nor did she have any on her that dreadful night in the ruins of the agora. Yes, it is terrible to admit that Alessia planned everything, because the question naturally arises: did she know that she was risking her life, or did she simply want to lose it? These pages are her artistic last will and testament. I’ve heard it said that literature is a pale metaphor of life. Alessia proves the contrary to be true. Was not what happened on Simena perhaps the corporeal dimension of her writing? She wrote first what she then lived. She must have given someone on the island the packet to send to me, afterward. She knew I would show it to you. If she wanted us to be her witnesses it was so that her quest for truth would not be lost, would not pass into silence. However questionable, it was genuine.

Tracey Emin, You Kept Watching Me, 2018

If you have the courage to give this diary to the authorities, they will probably grant Alessia’s jailors the benefit of extenuating circumstances. They will believe Ahmet Güluk, who maintained that he was provoked and driven against his will to do what he did with or without accomplices. You will have to endure the scandal. But it is also true that this is the only way to render justice to your wife. You must never forget that Alessia knew exactly what she was doing.

But Valerio my dear, who was Alessia? I ask you because you’ve held her in your arms. You should know her. To know. Did she lie to us? Or was it simply that in your arms she also felt that she was not whole? Or that something of herself constantly escaped her, something that obstinately and innocently went In search because it could not resist doing so? What did she find over there—she was so insistent that we go to Turkey!—that extinguished the light and thickened the darkness?

Tracey Emin, For One Year I Wrote to You Every Day, 2018

In these pages Alessia is no longer that introverted and dreaming girl who avoided conflict and suffered at every minor disappointment. The words that she uses, how she uses them, have more than once roused the little animal residing between my legs (as she herself calls it). Reading, I seem to be able to feel her excited breath on my neck, to see her hands hurry under her skirt, and this has made me eager to satisfy myself with my own hands. Does this seem crazy to you? Immoral? I’m inclined to believe that Alessia wrote specifically to excite herself. She knew that for these purposes the word is a good deal more eloquent and poignant than images. She created a red thread of connection between herself and her assassins well before the one between us. I don’t believe that her death was a tragic accident, as her aggressors claim. Rather, I think that at that point Alessia knew enough about herself to be able to set off the earthquake that would eradicate every shred of certainty in those boys, luring them down into the chasm into which she herself wished to plunge.

Tracey Emin, I Made You Happen, 2018

If the death of Alessia was agonizingly painful for you, it will be even more so now. Knowing her to be ignorant of herself, you could have continued to think of her with tenderness. Will you be able to sustain your love for her after having read? Will you ever find the strength to approach another woman without feeling like swooning with terror? I could have spared you, I know, but—forgive me—I cannot remain the sole guardian over her abyss, nor do I have sufficient strength to contain by myself the fear that lends the possibility of coming so near to life, to its source.

I know not what else to tell you, Valerio. Take care of yourself.

Luisa

Tracey Emin, Devoured by You, 2014

Women Writing Erotic Fiction

THE EROTIC SIGN

Maria Rosa Cutrufelli on Eros, Writing and the Feminine

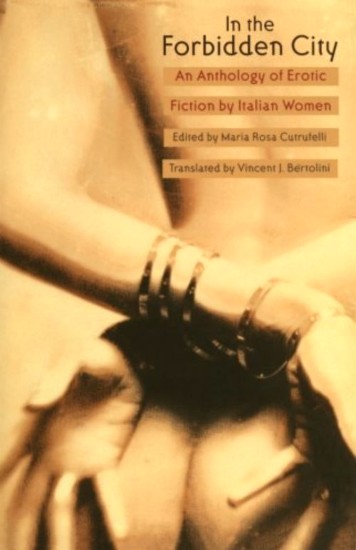

Posted by kind permission of Maria Rosa Cutrufelli

This is the complete text of the Introduction by Maria Rosa Cutrufelli to In the Forbidden City: An Anthology of Erotic Fiction by Italian Women, ed. Maria Rosa Cutrufelli, tr. Vincent J. Bertolini (University of Chicago Press, 2000) pp. 3-7

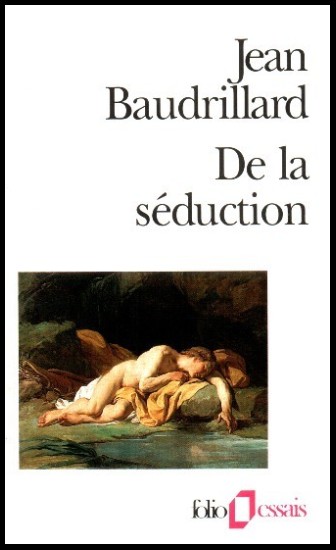

Femininity is a ‘principle of uncertainty,’ writes Jean Baudrillard (De la séduction, 1979). ‘It causes the sexual poles to waver. It is not the pole opposed to masculinity, but what abolishes the differential opposition, and thus sexuality itself.’

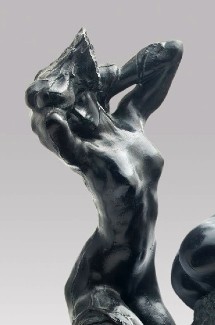

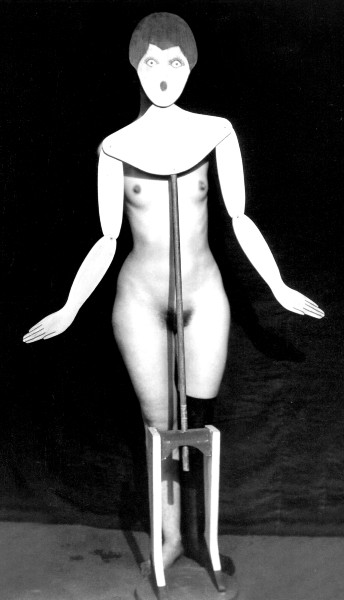

Man Ray, untitled, 1920

Baudrillard’s analysis is clear, straightforward, and consequential. ‘Freud was right,’ he writes, ‘there is but one sexuality, one libido—and it is masculine. Sexuality has a strong, discriminative structure centered on the phallus, castration, the Name-of-the-Father, and repression. There is none other. There is no use dreaming of some nonphallic, unlocked, unmarked sexuality. There is no use seeking, from within this structure, to have the feminine pass through to the other side, or to cross terms. Either the structure remains the same, with the female being entirely absorbed by the male, or else it collapses, and there is no longer either female or male—the degree zero of the structure.’ And this means the ‘neutralization’ of sex in the infinite potentialities of desire.

Fontainebleau School, Gabrielle d’Estrées and Her Sister, the Duchess of Villars, c.1594

Women are mistaken, maintains Baudrillard, to refuse the true power of the feminine, which is the power of seduction. Men exert the power of sex through political logic and within the economic order. But ‘seduction represents mastery over the symbolic universe, while power represents only mastery of the real universe.’

If, therefore, ‘anatomy is destiny,’ and this equation is ‘phallic by definition,’ then women are doubly mistaken when, in rejecting the prisonhouse of anatomy, they haul the body into court. If the word of the body is the word woman, then the circle closes on itself, since once again we are in the realm of the anatomical word, once again imprisoned.

Baudrillard’s position is, in all its clarity, very schematic. His argument is based on a simple binary logic: the body, in his view, is either a metaphor or a fate.

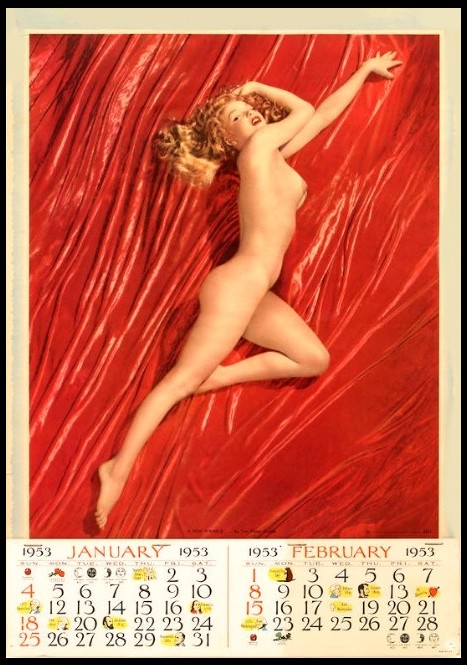

Pin-Up Calendar, Marilyn Monroe, 1953

Other theories of subjectivity, born simultaneously with modern feminist political praxis, follow more complex structures, putting the body, sexuality, and language into strict relation with one another. Such theories, not accidentally, all finally converge on a common interest: writing, and in particular, on women’s writing.

But what thread ties word and desire, sexuality and narrative, body and language in tight knots of interdependence? For the philosopher Rosi Braidotti, as for the semiotician Patrizia Violi, the body must not be understood as merely a biological or a sociological category, but rather as a point of overlap between ‘the physical, the symbolic, and the sociological.’ The body is, in short, ‘a surface of signification, situated at the intersection of the alleged facticity of anatomy with the symbolic dimension of language.’

Falconetti, The Passion of Joan of Arc, 1928

To simplify: the self is always marked by gender (I-she, I-he); it is, so to speak, an incarnated structure that ‘finds a voice,’ becomes a subject, and, paradoxically, ‘becomes a corpus, is engendered’ not in anatomy but in language. It is, therefore, language—and, consequently, representation—that is the site of the constitution of the subject.

JEAN BAUDRILLARD, PATRIZIA VIOLI, ROSI BRAIDOTTI

Baudrillard, De la séduction

Violi, Meaning and Experience

Braidotti, Nomadic Subjects

At the same time, as Teresa de Lauretis writes (in ‘Subjectivity, Feminist Politics, and the Intractability of Desire’, 1996), it is certainly the case that ‘sexuality is the site upon which the subject elaborates its image of itself, its own corporeal awareness and knowledge, its modes of relating and acting in the world.’ But sexuality is also the place of contradictions and ambivalences, of resistance and risk. Sexuality makes things problematic, precisely because it is the nodal point at which ‘instances of the corporeal, the psychic, and the social intertwine to constitute subjectivity and the limits of the self.’

Guido Reni, Salome – Head of John the Baptist, c.1641

Though at this point infinite avenues of inquiry open up, it is nevertheless clear why the question of language exerts such a charm upon feminist scholars. It is equally clear why sexuality presents itself as such a difficult and central theoretical node. It is through the enigmatic alchemy of body-sexuality-language that the dream of female freedom, of being and becoming a subject, of representing oneself as a subject, takes shape. The dream gains a dimension of reality when, at last, the word is translated into writing.

Johannes Vermeer, A Lady Writing, c.1665

The true and proper passion of many women for the practices of writing has its origin here, in this process of construction and representation of oneself as a subject. But in this process sexuality plays an ambiguous role. Erotic desire and activity (which constitute the plot, the meshwork stretched upon the loom of sexuality) can be implosive, fragmenting, incoherent. Narrative, the literary account, often emphasizes the ostensibly triumphant subject’s sensation of being eclipsed as it penetrates into the darker and more secret mazes, the more unexplored recesses of desire. But with what consequences?

‘Eros is at work in all writing,’ writes the Canadian theorist Nicole Brossard. And one immediately asks, what might this mean for women? To which body is Eros being here referred? Which body, which desire, which subject is passing through the writing?

Joos van Cleve, Lucretia, c.1520

This is a question one must inevitably pose in the long voyage of exploration toward sexuality. And one of the most arduous journeys is certainly the one that leads us into the ‘forbidden city’ of erotic literature, which the writer Marisa Rusconi calls ‘virtually a scorched earth, without pre-existing roots or sprouts.’ Female erotic writing is an enterprise that, in order to achieve its fullest realization, requires many diverse voices and narrations, given the many different experiences each one of us carries with us and brings to bear along the way.

Guido Cagnacci, The Suicide of Cleopatra, c.1661

Which body, which desire, which subject—which sexuality? A question that has already received many answers, as many as there are stories authored by women, which with ever more frequency, using different (often radically different) means and forms, enter the gates of the ‘forbidden city,’ of the kingdom of Eros.

Many women authors have tried to construct maps, to delimit borders. In these literary cartographies of sexuality and of erotic desire, experimentation is, for many such writers, the primary navigational tool. Austrian women writers perhaps most of all, Liesl Ujvary, Waltraud Anna Mitgutsch, Elfriede Jelinek, and others, have closely linked linguistic innovation—the subversion of traditional structures, even the rupture of grammatical conventions—to the theme of the erotic. Some have used a broken language, a distorted literary sign, to explore female eroticism.

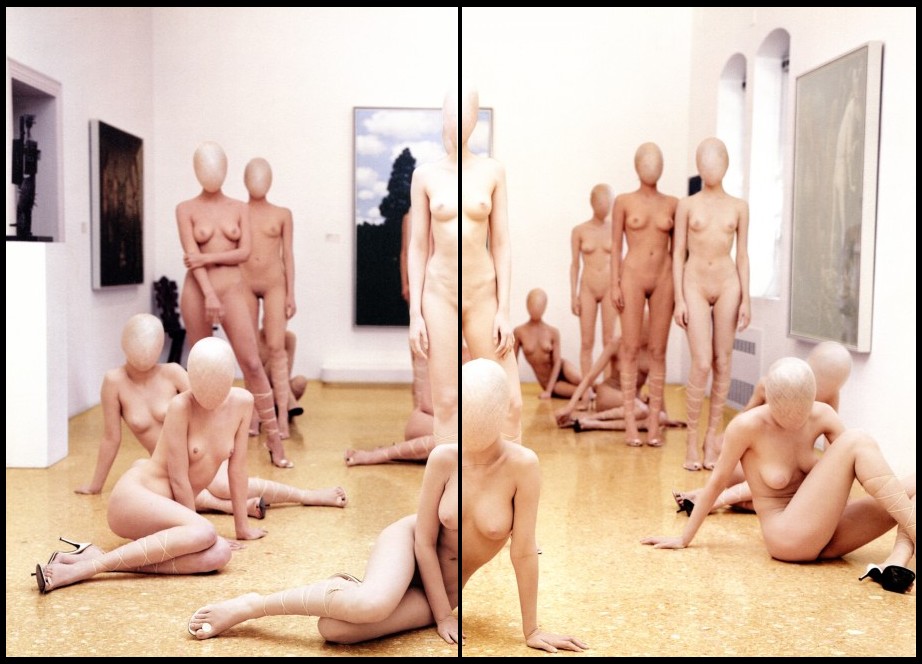

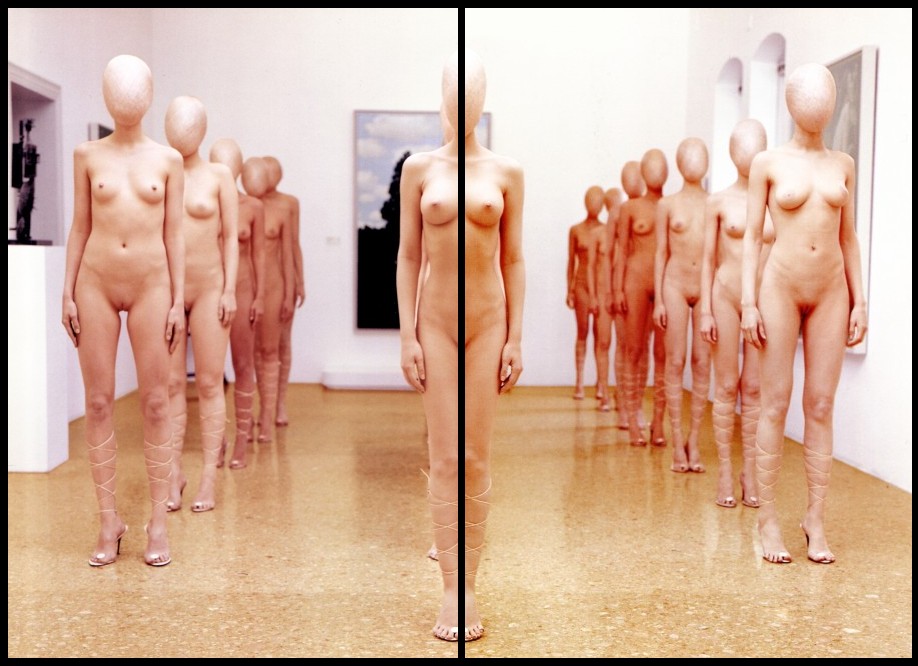

Vanessa Beecroft, vb47.341.dr, 2001

Others have instead sought new expressive means to unmask the ‘male gaze’ upon the body of women. Elfriede Jelinek, in particular, proceeds by negation, using in her novels an imitative language drawn from magazines ‘for men’ and from advertising. Her aim? ‘To reconquer the representation of the obscene and of nudity,’ a representational project ‘usurped by men to such an extent that no room remains for women to take up similar issues, and thus they are destined to fail if they try.’

Vanessa Beecroft, vb47.355.dr, 2001

Her own effort ultimately fails as well, as she herself admits, though it might be called ‘a constructive failure.’ To proceed exclusively by negation cannot be effective: this strategy leaves the male gaze single and unitary, and male desire can still rule uncontested over the territory of Eros. Jelinek’s novels are ‘political,’ novels of denunciation. And yet, paradoxically, they were largely rejected by critics who accused them of being pornographic. Obscenity, pornography, eroticism—the boundaries between these concepts are labile, subjective. They shift according to changing epochs, tastes, customs.

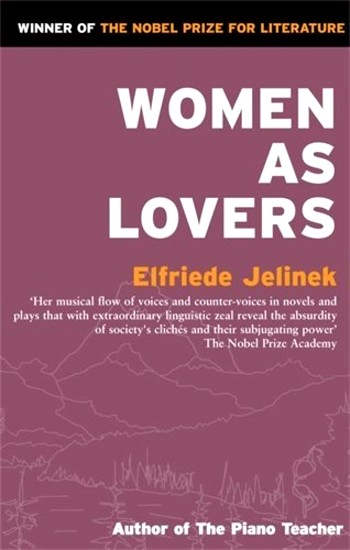

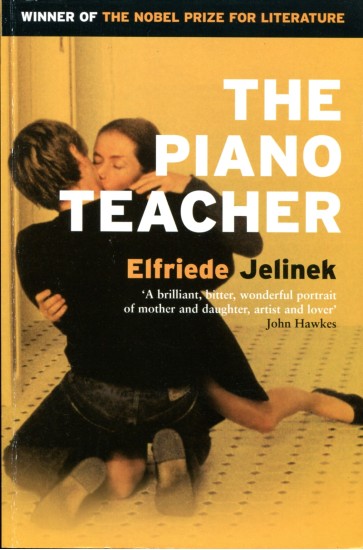

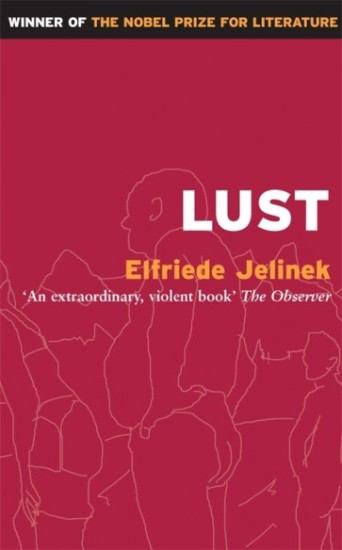

ELFRIEDE JELINEK: THREE NOVELS

Women as Lovers

The Piano Teacher

Lust

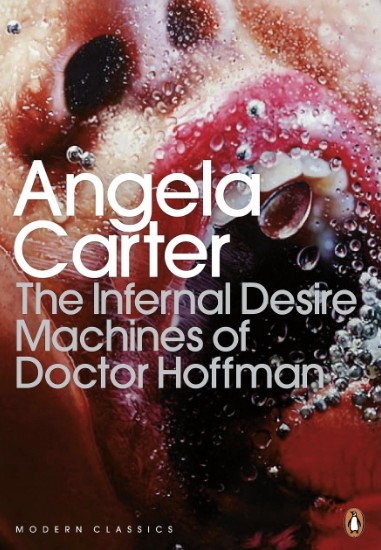

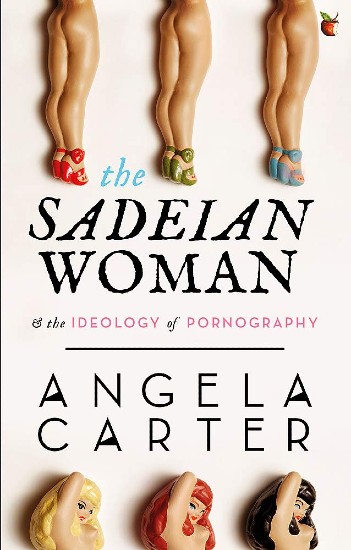

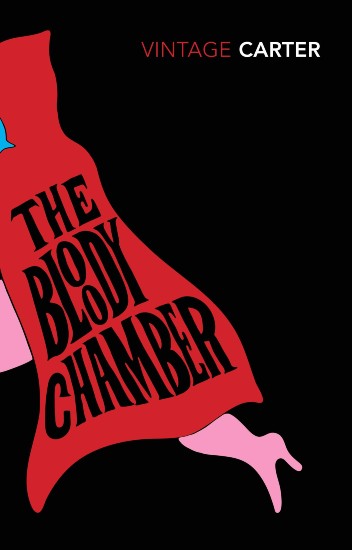

Angela Carter, who in her novels writes about the ‘mistresses of the whip,’ of female slaves and sadistic pleasures, shrewdly observes, ‘I believe that people find many different things erotic, and I find it difficult to generalize. Perhaps one characteristic of erotic literature, if I had to try to define it as a genre, is that of not taking sex for granted.’ Eroticism, generally speaking, ‘problematizes sex,’ while in pornography ‘sex is everywhere, in every form, is a consumer product that loses its value.’

ANGELA CARTER: ‘NOT TAKING SEX FOR GRANTED’

Angela Carter, Infernal Desire…

Angela Carter, Sadeian Woman

Angela Carter, Bloody Chamber

Erotic literature, on the other hand, is precisely the exploration of the boundaries between the obscene and the erotic, between pornography and erotic art, between the great temptation and the great challenge. This play of stereotypes within the genre—what is masculine, what is feminine, what belongs to men, what to women—is conducted along a very fine edge and is always dangerously balanced between convention and transgression. But in life as in literature, all of our cards have now been shown, and the game is changed. Mere transformation is now all too obvious, in the relations between the sexes as in the relations between each individual and herself.

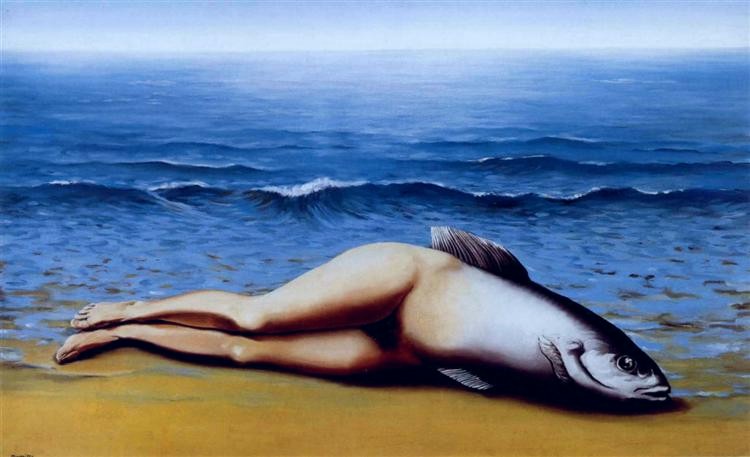

René Magritte, The Collective Invention, 1935

If we analyze the literary production of the last decades, we immediately see that excess and cruelty, violence, sadism and masochism are not exclusively (no longer?) marks of the male sexual imaginary. But for many female writers the question remains, does this yet again indicate some kind of mirroring, some mimesis of the masculine?

Minoan Snake Goddess, c.1600 BC

Angela Carter replies, ‘Female sexuality has been seen alternately as non-existent or uncontainable, to be negated through the imposition of the value of virginity, or to be controlled through the practice of monogamy and through other forms of restriction. There has been a grand stereotyping of female sexuality. Women in Western (and not solely Western) culture are represented as beings determined by sex, alternately obsessed by or alienated from their needs.’ Stereotypes, clichés whose durability is based precisely on the undemonstrability of that which they assert. Women, it is said, more strictly equate sex with love, are more concerned with the emotional component of sex, have more pronounced difficulty separating feeling from the sexual relation. According to Carter, all this is an invention, or rather, a ‘cultural convention.’ For others, however, in this undoubted ‘historical invention’ lies the germ of ‘difference,’ of a possible alternative route, not yet well delineated, ungraspable, and nevertheless present.

THE EXPERIENCE OF SEX: THREE WOMEN WRITE

At this point, it is worth taking a step backward. There exists a cultural, philosophical, and literary tradition that has the ‘erotic eye’ coincide with the ‘sadistic eye’—a masculine tradition par excellence.

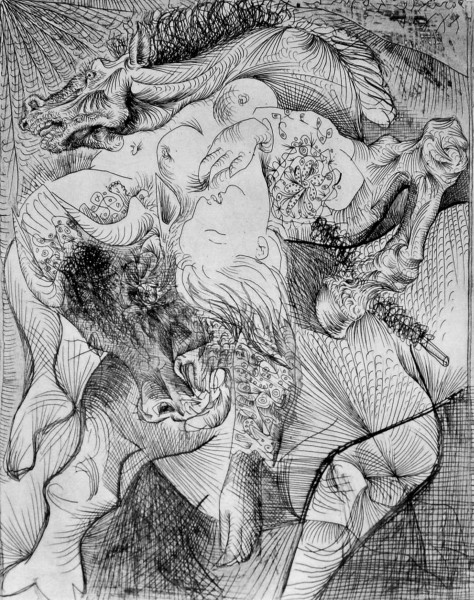

Picasso, Bull, Horse, Woman, 1934

Eroticism is a form of knowledge that writers and philosophers have from time to time tied to an idea of loss and of suffering, a feeling of dissipation, and a ‘strong’ concept of power from which there is no escape. The erotic experience, wedded in this way to mystical experience, destroys reality at the very moment in which it discovers it. In his introduction to Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye, Alberto Moravia writes, ‘The sexual relation, like Attila, leaves no grass on the ground over which it passes. It creates desert around itself and calls that desert ‘reality.’ Since it projects man outside of the world, the erotic experience is a devaluation and rejection of the world itself. And no return is ever possible, as Moravia writes: ‘The bridges are burned; the real world is lost forever.’

Georges Bataille, Story of the Eye

This grandiosely tragic vision of the power of sex is by no means unfamiliar to women. But there is a difference, the difference that for women, return is always possible. The cancellation of the world is never total, never definitive. Destructiveness is not an obsession. Alina Reyes, who achieved success in France with her first published work, an erotic tale, has explained with great simplicity: ‘Male eroticism is too enslaved to its ghosts, its stereotypical and repetitive fantasies, voyeuristic imaginings; at bottom, to abstractions. Women, instead, are more tied to the concrete experience of the flesh, to matter.’

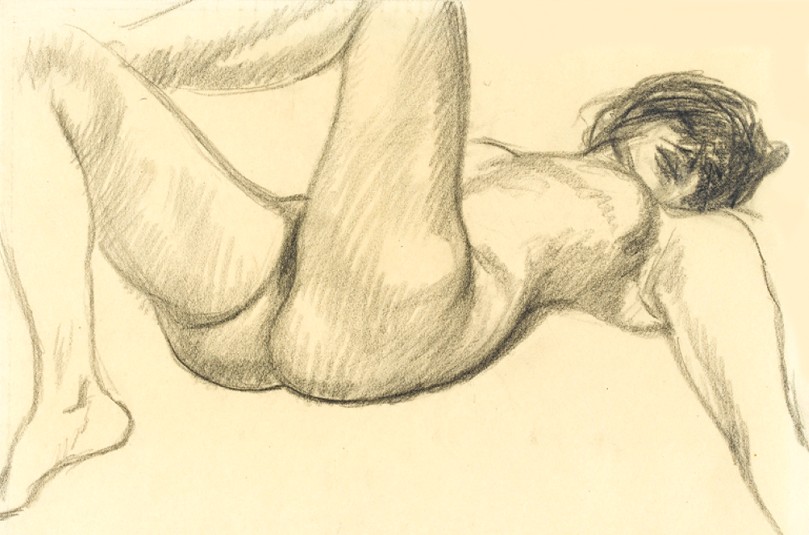

Steinlen Théophile Alexandre, Reclining Nude, before 1923

Matter, flesh, the body, and the word that, in representing the body, in narrating desire, constructs a new subject, a subject of words who does not render her body a neutral potentiality, an undifferentiated sexual force. It is for this reason, perhaps, that female-authored erotic stories tend to be regarded as either simple ‘repositories of perversions’ or pure ‘philosophies of sex.’ Such stories, quite to the contrary, move with grace or with power, with drama or with irony, through a kind of writing that draws not ‘one’ sexuality (a fixed model, outside of time and history), but the various ways of living sex. Thus, contrary to what Baudrillard maintains, the infinite possibilities of desire can incarnate themselves in an ‘I,’ can find body and voice in a ‘subject.’

Johan Tobias Sergel (1740-1814), Venus and Anchises

In Italy, it is rare for women writers to dare to enter within the walls of the ‘forbidden city.’ We do not have, in contrast to other countries, our own actual tradition of female-authored erotic literature. Representations of eros and stories of sex, today as yesterday, remain on the margins of Italian women’s writing. But the impression one gets is that, just under the surface, the swelling river of erotic narration is flowing, and at times bursts powerfully through. I am thinking of Francesca Sanvitale’s cruel and tormented Reality Is a Gift: Stories as well as a previous novel that created scandal, A Girl Called Jules by Milena Milani. The authors in this anthology—the first of its kind in Italy—belong to different generations; they are quite diverse in their use of tone and narrative style, and diverse, too, in terms of the way that each understands eroticism. They represent individual women’s voices that narrate and explore distant worlds, often quite alien to each other: the ancient temptations of sadomasochism, the close tie between amorous emotions and the emotions of sex, the elusive games of seduction. Sex, the raw sexual impulse, remaining at times in the background of these stories, is periodically invoked, and then returned to its simple function as a narrative expedient. Different in intention—therefore, different in tone. But, having accepted the task of writing a story that was erotic ‘by design,’ all of the writers appearing in this anthology proved to have something in common: a relish for the challenge, a passion for delving. Because, in the final analysis, In the Forbidden City is none other than this: a plumbing of the depths, an immersion—cautious or daring, enervating or vigorous—in the current, still subterranean, of ‘our’ erotic narrative.

Maria Rosa Cutrufelli, In the Forbidden City

IPPOLITA AVALLI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 14

̶ So, what are you up to these days? you ask Riva.

̶ Translation. I’ve just finished an anthology of erotic fiction. By women, of course.

̶ Of course. French to Italian, or the other way around?

̶ The other way around. Italian to French.

̶ And how long have you been working as a translator?

̶ You don’t remember?

̶ No.

̶ I’d already started when I was going out with Inès.

̶ Is that so?

̶ Yes. Now I can afford to translate only what I like.

̶ You must be very good.

̶ I’ve worked hard…

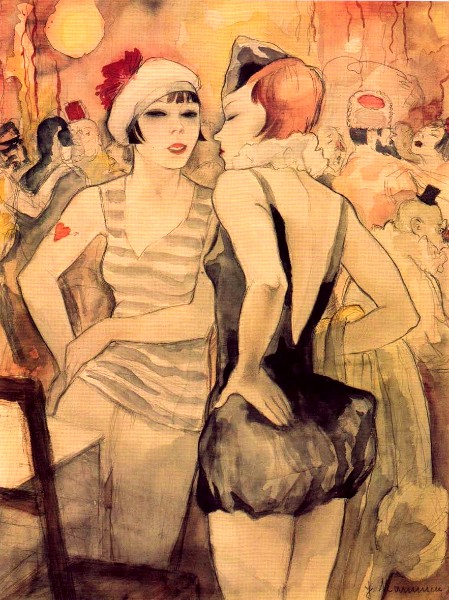

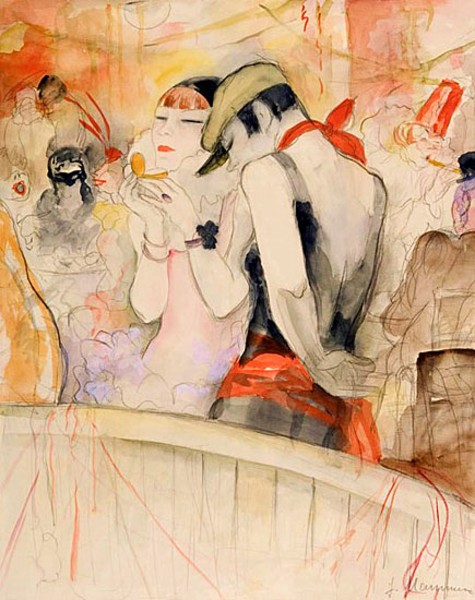

Jeanne Mammen, Carnival II, 1931

So this is Riva, the woman who, before she met Inès, had never had an erotically satisfying relationship. Neither with a man nor a woman. Struggled against her homosexuality. On experiencing its power, she was shocked and desperate, appalled at her own response. Felt condemned, as if she’d just signed her own death sentence. This Inès told you in the Lounge of Neon Lies.

Jeanne Mammen, Carnival I, 1931

̶ You know, Marietta, there’s a story in the anthology that makes me think of you.

Never experimental, never casual, never promiscuous: That, we would learn, was how Riva was in all her affairs: Serious. Always serious.

̶ Yeah, really?

̶ Yes. It’s by Ippolita Avalli. It’s called ‘Simena’.

̶ I’ve read it. Ten times. That’s how much I love it.

̶ But my translation’s not out yet!

̶ Have you forgotten I’m perfectly at home in Italian? But if it would please you, I’ll read your French translation.

̶ No, no, if you’ve already read the original…

Jeanne Mammen, She Represents, 1928