JIM MORRISON, POET

Richard Jonathan

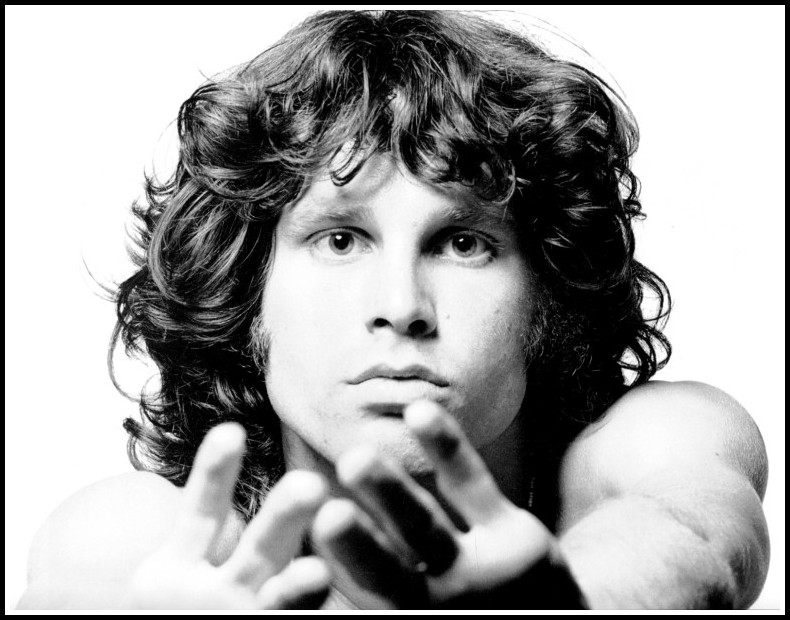

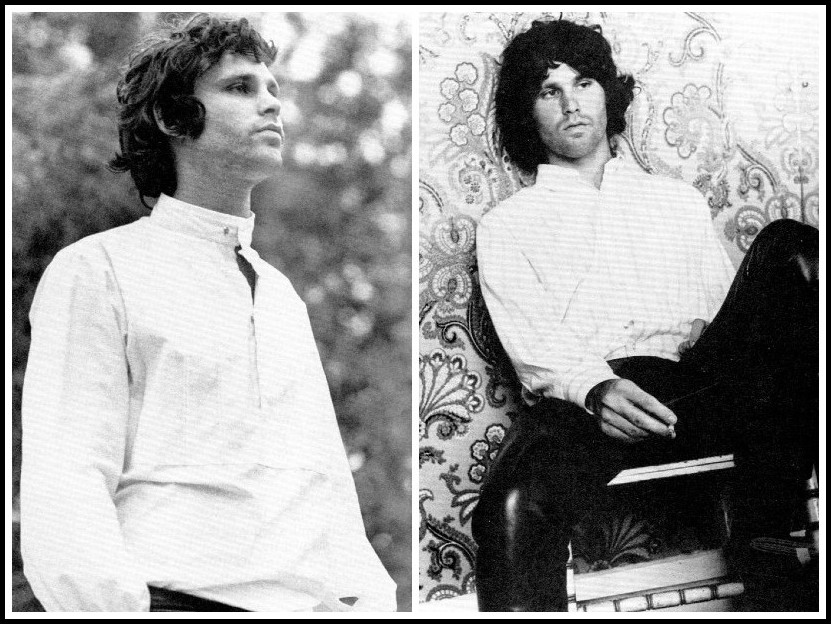

Jim Morrison | Photo: Joel Brodsky

I – JIM MORRISON: AN ACCIDENTAL ROCK STAR

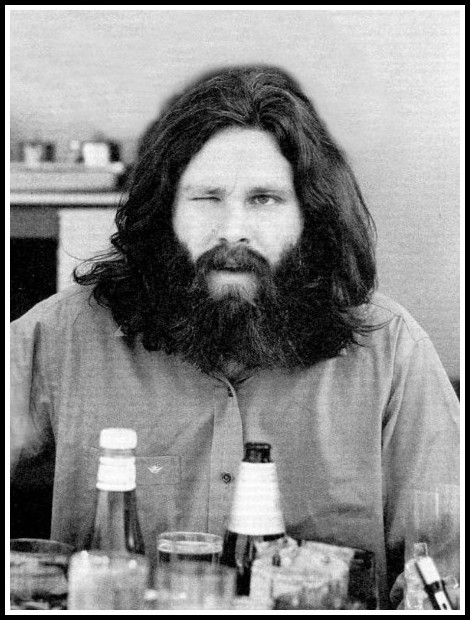

Jim Morrison was an accidental rock star, a man who walked backwards into the music business: His eye was always on the printed word (interview, eighth question from the end). The maelstrom of the sixties, before it swallowed him up, offered him a wave of turbulent confusion that he surfed with style and talent until alcohol—see the autobiographical poems further down in this post—turned him into an ‘asshole’. Before his return to the womb in that Paris bathtub, he left a body of work that, thanks to the genius of the Doors, is as vital and stimulating as it was half a century ago. Now, as the age becomes increasingly imbecilic—for so many, the marriage of invasive technology and hyperconsumerism has sealed off the soul with a wall of permanent amusement—I have no doubt that Morrison’s lyrics and the Doors music (that ‘rose of mysterious union’) will continue to cast their luminous darkness, their joyful seriousness, there wherever the vigilance of angels safeguards silence.

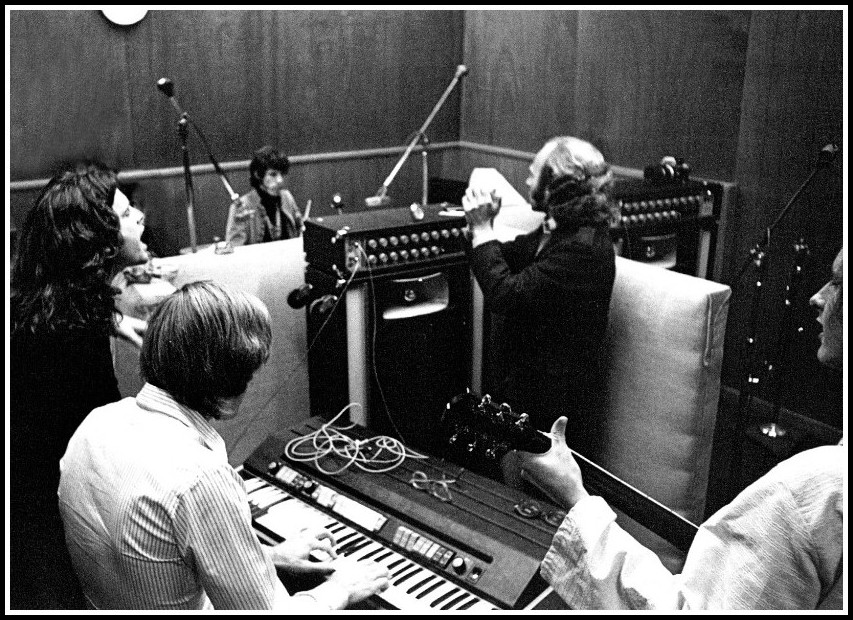

The Doors with producer Paul Rothchild | Photo: Paul Ferrara

II – THE HERO’S JOURNEY

Upon graduating from high school, Jim asked his parents not for the traditional car, but for the collected works of Nietzsche (interview). From the time he could talk, he had a feeling for the heightened language we call poetry. He was a voracious reader, kept notebooks with words and quotations from his readings. By his late teens, thanks no doubt to Rimbaud and Nietzsche—Nietzsche for the marriage of philosophy and poetry, Rimbaud for the example of the seer—esoteric knowledge was flowing in his veins. How did he acquire it? After all, as Adam Phillips says in The Beast in the Nursery, ‘only hunger turns food into a meal, it is appetite that makes things edible’. So what made Jim hungry when the vast majority were satisfied, what was the crack that let in the light? Jim gives the answer in ‘Dawn’s Highway’ and ‘Newborn Awakening’ on An American Prayer: ‘Indians scattered on dawn’s highway bleeding, ghosts crowd the young child’s fragile eggshell mind’. He was marked, then, like all who are not ‘at home’ in the world, by a foundational trauma. (What confuses many is the fact that he was so at home—like a fish in water, like a drunk in wine—in the topless bars of Venice, in the decenteredness of L.A.) This trauma—this vision of dead Indians bleeding exceeding discursive knowledge and so unassimilable—was the necessary condition for his acquisition of esoteric knowledge.

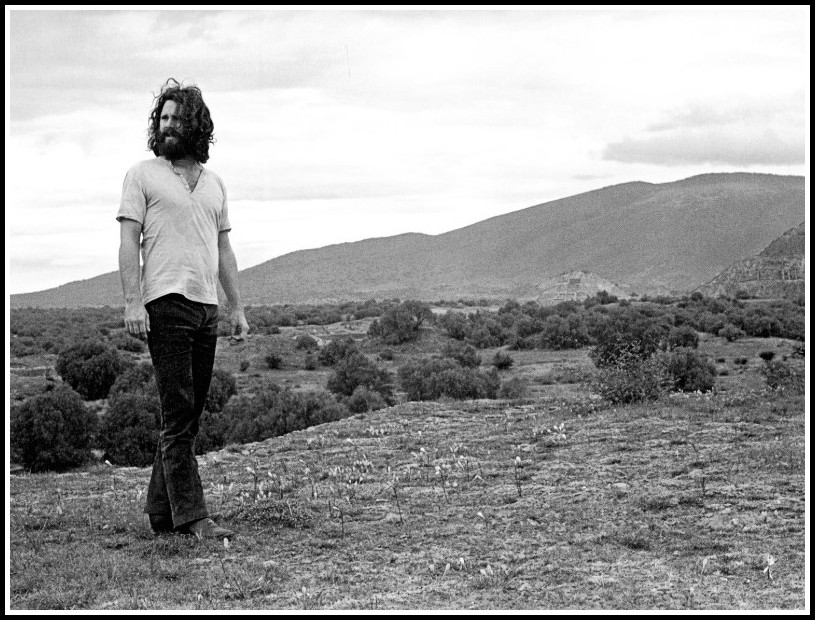

Jim Morrison | Photo: Michael Montfort

All Jim’s poetry, then, is informed by the knowledge available only to the initiated, the knowledge ‘the ghosts of the dead Indians that leapt into [his] soul’ impelled him to acquire. But where exactly did that knowledge come from? From whatever conductor of the numinous Jim came across: the via negativa that opens the doors of perception or the mansions of the mind that open up to the wayfarer’s gaze, the awe and mystery of the black side of the holy or the living-in-depth that journeying along the axis mundi entails. And in what does that knowledge consist? In a nutshell: The insight that truth is hidden, the visible world illusion, and only a quest to attain the transcendent can procure wisdom. As every Doors fan knows, the images of this in Jim’s poetry are numerous: ‘break on through to the other side’, ‘take a journey to the bright midnight’, ‘I want to hear the scream of the butterfly’.

Jim Morrison | Photo: Jerry Hopkins

III – HEIGHTENED LANGUAGE

‘All intensified knowledge sooner or later turns metaphorical, and literature is the inescapable guide to higher journeys of consciousness’*. Paradoxes, unusual verbal juxtapositions, are but one means the poet has at his/her disposal to ‘break on through to the other side’. Again, these abound in Jim’s poetry. A few examples: ‘Insanity’s horse adorns the sky / Can’t seem to find the right lie’, ‘Carnival dogs consume the lines / Can’t see your face in my mind’; ‘The music was new, black polished chrome / And came over the summer like liquid night’; ‘We need golden copulations / The fathers are cackling in trees of the forest’; ‘The streets are fields that never die’; ‘My eyes have seen you / Let them photograph your soul / Memorize your alleys / On an endless roll’; ‘Shadows of the evening / Crawl across the years’. As he pursues the initiate’s journey, then, Jim’s poetry paints us ‘inscapes’ of his consciousness.

* Northrope Frye, Words with Power: Being a Second Study of the Bible and Literature [Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990] p.28

Jim Morrison | Photo: Ray Manzarek

GIORGIO AGAMBEN & JORGE LUIS BORGES: THE LANGUAGE OF POETRY

Giorgio Agamben: ‘Poetry lives only in the tension and difference between sound and sense’. (Paul Valéry: ‘The poem: a prolonged hesitation between sound and sense’.)

Giorgio Agamben, The End of the Poem: Studies in Poetics, tr. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford University Press, 1999) p. 109 | Paul Valéry, Tel Quel, Gallimard Folio Classiques, 1996) in the section entitled ‘Rhumbs’

Giorgio Agamben: ‘In our culture, knowledge is divided between inspired-ecstatic and rational-conscious poles. Insofar as philosophy and poetry have passively accepted this division, philosophy has failed to elaborate a proper language, as if there could be a royal road to truth that would avoid the problem of its representation, and poetry has developed neither a method nor self-consciousness. What is thus overlooked is the fact that every authentic poetic project is directed toward knowledge, just as every authentic act of philosophy is always directed toward joy.’

Giorgio Agamben, Stanzas: Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, tr. R.L. Martinez (University of Minnesota Press, 1993) p. xvii

Jorge Luis Borges: ‘Words began not by being abstract, but rather by being concrete. Let us consider a word such as “dreary”: the word “dreary” meant “bloodstained”. Similarly, the word “glad” meant “polished”, and the word “threat” meant “a threatening crowd”. Those words that now are abstract once had a strong meaning. Therefore, when speaking of poetry we may say that poetry is not trying to take a set of logical coins and work them into magic. Rather, it is bringing language back to its original source.’

Jorge Luis Borges, This Craft of Verse: The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, 1967-1968 (Harvard University Press, 2000) pp. 79-80

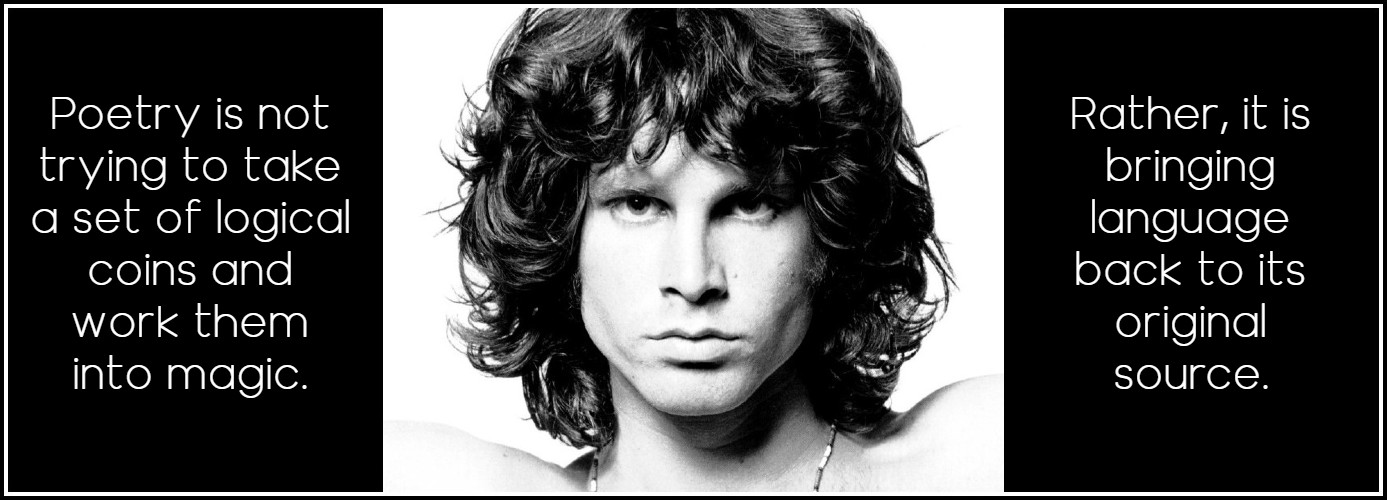

Jim Morrison | Photo: Joel Brodsky | Text: Jorge Luis Borges

IV – TRANCE

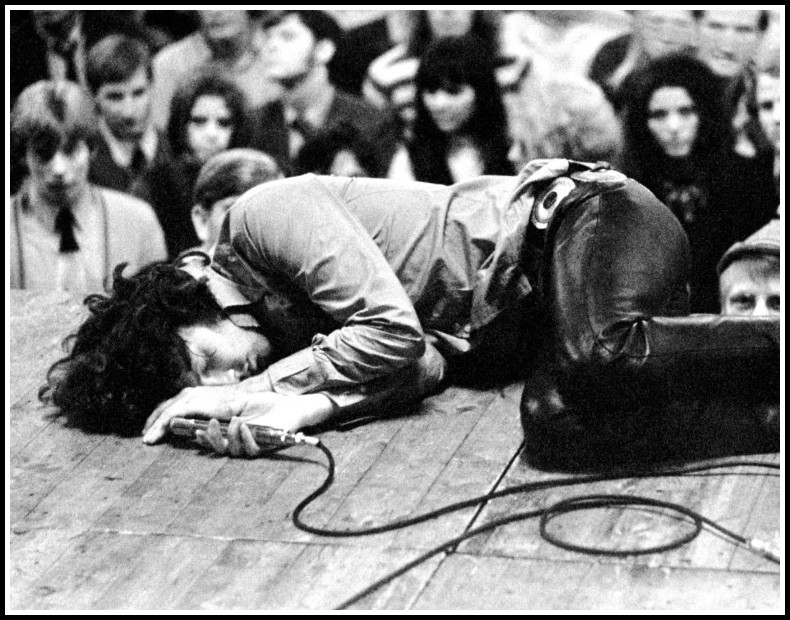

Trance is another means Jim uses to attain the transcendent: ‘To speak to the heart / And give the great gift / Words Power Trance’. Jim has often said that in lieu of finished songs, in lieu of closure, he prefers the openness of improvisation: ‘I like singing the blues – these free, long blues trips where there’s no specific beginning or end. It just gets into a groove, and I can just keep making up things … I like that kind of song rather than just a song … just seeing where it takes us (interview). In other interviews, Jim also spoke often of performance-as-ritual. Most of the time, however, his drunkenness and the juvenility of the audience impeded his attempts at trance. Nevertheless, his performance ideal was to use words/music to generate music/words and this in turn to generate trance, and then in a spiral up the axis mundi, trance to generate more words and music, and so on until transcendence is attained. Much of his poetry, then, employs language in the service of this ideal.

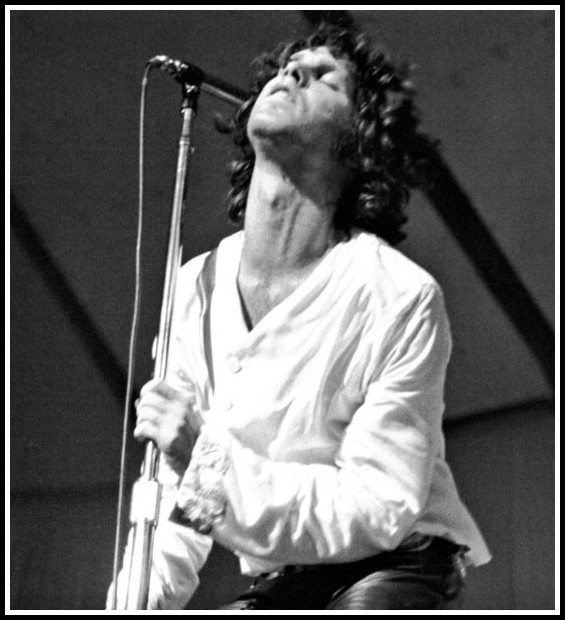

Jim Morrison | Photo: Ethan Russell

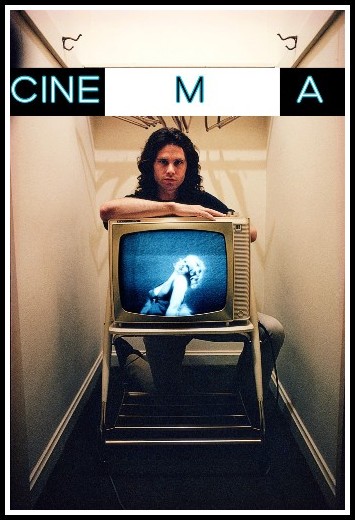

V – CINEMA, LANGUAGE, POETRY

JIM MORRISON: SIX MUSINGS ON CINEMA

From Jim Morrison, The Lords and the New Creatures (Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 1987) pp. 64-69, 86-87. First published in 1969 & 1970.

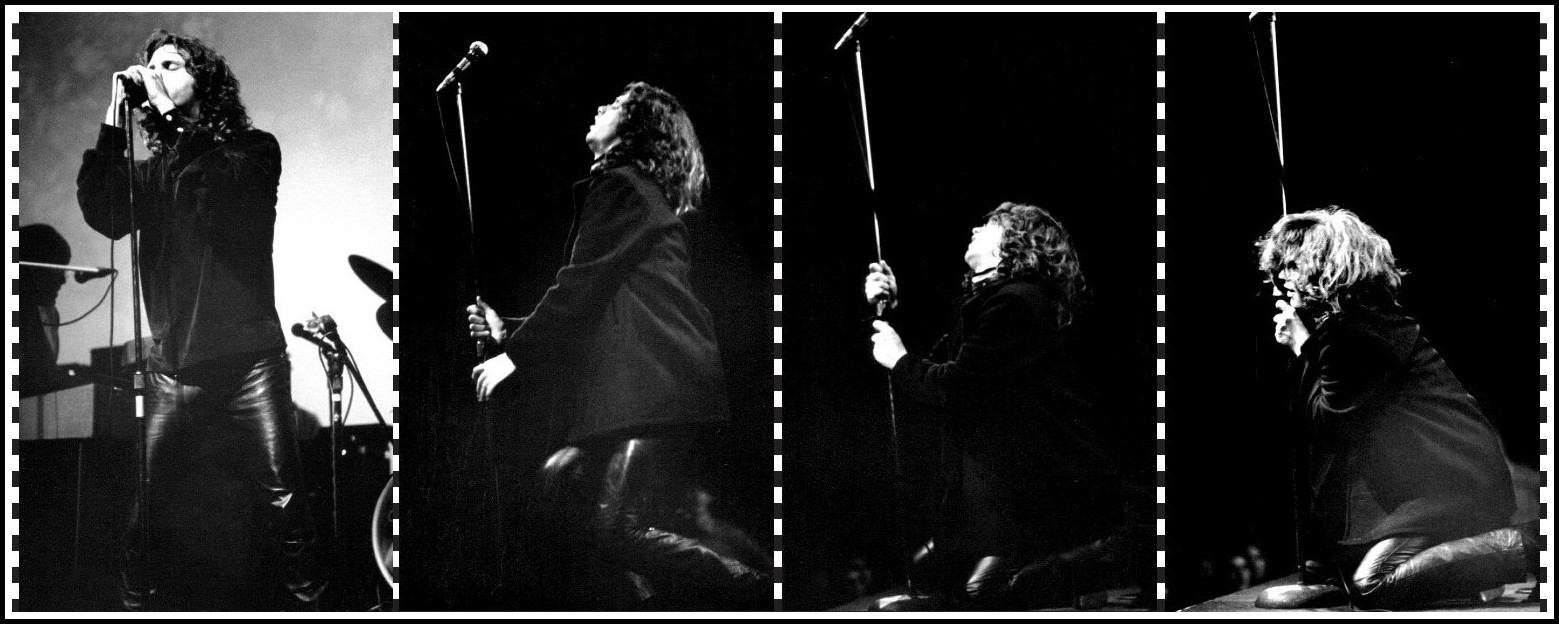

Jim Morrison | Photos: Ken Regan

I

Cinema has evolved in two paths.

One is spectacle. Like the Phantasmagoria, its

goal is the creation of a total substitute

sensory world.

The other is peep show, which claims for its

realm both the erotic and the untampered observance

of real life, and imitates the keyhole or

voyeur’s window without need of color, noise,

grandeur.

Jim Morrison | Photo: Art Kane

II

Cinema discovers its fondest affinities, not

with painting, literature, or theater, but with

the popular diversions—comics, chess, French

and Tarot decks, magazines, and tattooing.

Jim Morrison | Photo: Art Kane

III

Cinema is the contemporary manifestation

of an evolving history of shadows, a delight in

pictures that move, a belief in magic. Its

lineage is entwined from the earliest beginning

with Priests and sorcery, a summoning of phantoms.

With, at first, only slight aid of the mirror and

fire, men called up dark and secret visits from

regions in the buried mind. In these seances,

shades are spirits which ward off evil.

Jim Morrison | Photo: Art Kane

IV

The spectator is a dying animal.

Invoke, palliate, drive away the Dead. Nightly.

Jim Morrison | Photo: Art Kane

V

Strange, fertile correspondences the alchemists

sensed in unlikely orders of being. Between

men and planets, plants and gestures, words and

weather. These disturbing connections: an infant’s cry

and the stroke of silk; the whorl

of an ear and an appearance of dogs in the yard;

a woman’s head lowered in sleep and the morning

dance of cannibals; these are conjunctions which

transcend the sterile signal of any ‘willed’ montage.

These juxtapositions of objects, sounds,

actions, colors, weapons, wounds, and odors shine

in an unheard-of way, impossible ways.

Film is nothing when not an illumination of

this chain of being which makes a needle poised

in flesh call up explosions in a foreign capital.

Jim Morrison | Photo: Art Kane

VI

Cinema returns us to anima, religion of matter,

which gives each thing its special divinity and

sees gods in all things and beings.

Cinema, heir of alchemy, last of an erotic science.

Jim Morrison | Photo: Art Kane

Jim’s poetry has a strong cinematic dimension. Andrzej Zulawski (a Polish filmmaker whose first film, The Third Part of the Night, was released in the year of Jim’s death), was a filmmaker whose films, especially Chamanka (She-Shaman) and Possession, are perfect expressions of Jim’s ethics and aesthetics (for the true artist, the two are always intimately entwined). Zulawski’s films enact the trance Jim sought as a means to transcendence, they embody Jim’s conception of cinema: ‘Film is the closest approximation in art that we have to the actual flow of consciousness, in both dream life and the actual perception of the world’ (interview). The most consistent cinematic equivalents of Jim’s poetry, then, are the films of Zulawski. Indeed, ‘The End’ and ‘When the Music’s Over’ can be seen as aesthetic precursors of Chamanka and Possession.

Andrzej Zulawski, Possession, 1981

VI – THE MYTHICAL DIMENSION

In Jim’s poetry a mythical dimension often attaches to words, giving them—like phosphorus exposed to oxygen—a particular glow. The butterfly in ‘the scream of the butterfly’ suffices unto itself, but attached to the insect—for listeners with attuned antennae—is its mythical dimension as ‘the soul freed from its covering of flesh’. In ‘The End’ the snake is clearly mythical: great god of darkness; symbol of both soul and libido; storehouse of potential underlying the palpable world. Night, as we have already seen, is an emblem of ‘the other side’; the word recurs in many songs. In ‘Moonlight Drive’, the moon is awash in mythical associations, giving access to the ‘strait gate’ which opens upon release and light, a short cut to the luminous centre of being and oneness. And what about in ‘Wild Child’? Who is that ‘ancient lunatic [who] reigns in the trees of the night’? A witch, a black moon, a decrepit madman?

Photos: Aarn Giri | Cai Carney | James Wainscoat

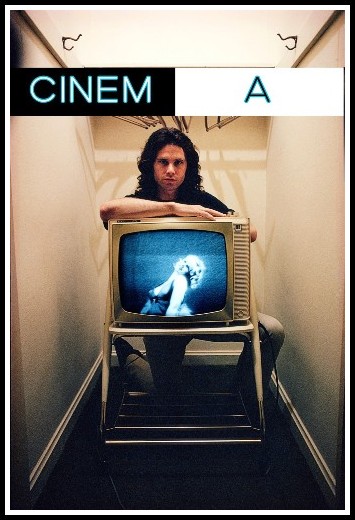

VII – THE PROPHETIC DIMENSION

A prophetic dimension is present in several of Jim’s poems (‘When the Music’s Over’, ‘Ship of Fools’, ‘Not to Touch the Earth’), but it is in ‘The End’ where we perceive this dimension most clearly. The prophetic in literature, write Northrope Frye, ‘indicates the quality of the poet’s authority’. He cites the example of Amos in the Old Testament, who ‘has the refusal to compromise with polite conventions, a reputation for being a fool and a madman, and an ability to derive the substance of what he says from unusual mental states, often allied to trance’. Frye points out that in modern times, ‘the writers we instinctively call prophetic—Blake, Dostoevsky, Rimbaud—show similar features. Such writers shock and disturb; they may be full of contradictions and ambiguities, yet they retain a curiously haunting authority’.

* Northrope Frye, Words with Power: Being a Second Study of the Bible and Literature [Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990] p.53

Dennis Creffield, William Blake, c. 1985 | Matheus Chiaratti, Rimbaud & Verlaine Forever, 2018 | Jan Lenica, Dostoevsky’s The Possessed, 1970

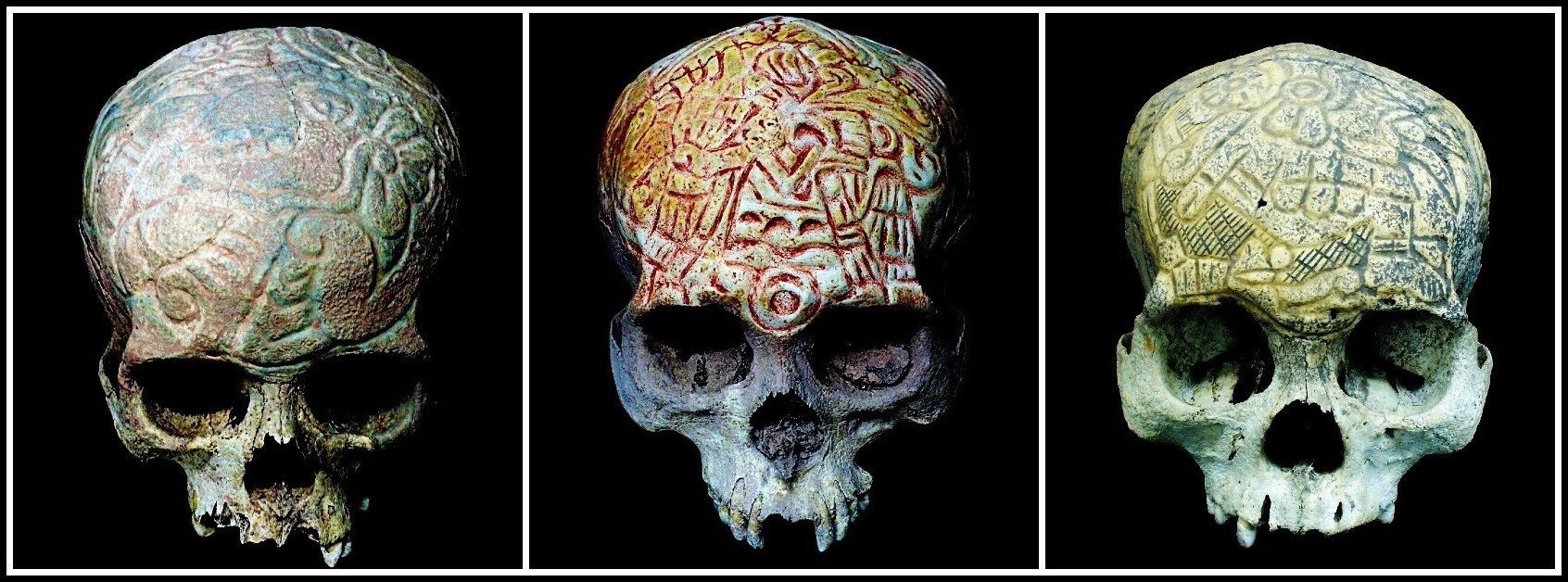

What gives ‘The End’ its ‘haunting authority’? What—besides the brilliance of the music—makes it so powerful? It is, I would argue, the fact that it reaches deep down into a mythical, primitive psychology and then evokes cinematically what the poet found there. In a 1968 interview with the Los Angeles Free Press, Jim said: ‘I used to have this magic formula to break into the subconscious. I would lay there and say over and over “Fuck the mother, kill the father. Fuck the mother, kill the father”. You can really get into your head just repeating that slogan over and over. Just saying it can be the thing’. Now, ‘the connection with the psychologically primitive characterizes the prophetic writer’, says Frye (p. 54). Jim would agree, and would be quick to make it clear that, to the extent that he is working in a mythological dimension, the ‘prophetic’ is not about foretelling the future, but rather about highlighting the fact that history is a series of repetitions. Thus, just as in film where every image on the screen is in the present tense, not matter where it is situated in the narrative sequence, so in ‘The End’ the ‘stranger’s hand in a desperate land’, the ‘Roman wilderness of pain’, the ‘snake’ and the ‘blue bus’, the killer who ‘walked on down the hall’, are all immediately present to us, even as they resonate through past and future centuries. This is a particular quality of Jim’s poetic genius, and this is what I characterize as the prophetic dimension in his poetry.

Cráneos Zapotecas | Museo Casa del Mendrugo, Puebla, México

VIII – GHOSTS

If ‘The End’ is, as I believe, the finest poetic achievement in all of rock (matched only, perhaps, by ‘A Day in the Life’), we owe it to the ghosts who entered Jim’s soul when he was four years old. It is thanks to those dead Indians that Jim became the artist he became, and it is their recurring death that gives his poetry its prophetic dimension. An extravagant thesis, I admit, but wasn’t Jim one for extravagance?

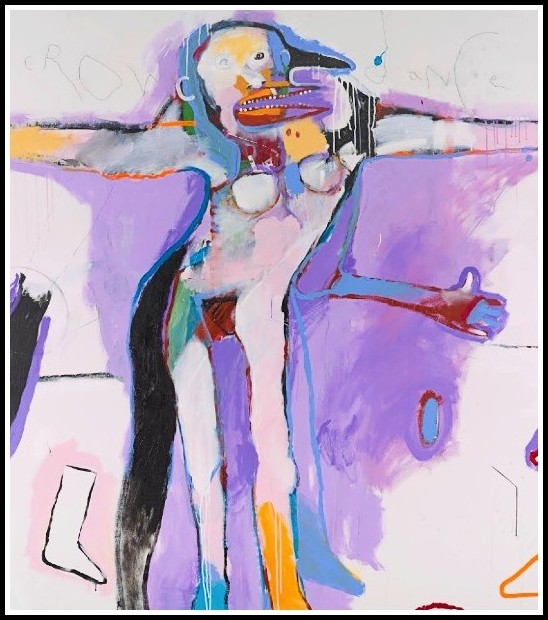

Rick Bartow (1946-2016), Wiyot Indian (detail)

JIM MORRISON: I’LL ALWAYS BE A WORD MAN

‘Listen, real poetry doesn’t say anything, it just ticks off the possibilities. Opens all doors. You can walk through any one that suits you. And that’s why poetry appeals to me so much—because it’s so eternal. As long as there are people, they can remember words and combinations of words. Nothing else can survive a holocaust but poetry and songs. No one can remember an entire novel. No one can describe a film, a piece of sculpture, a painting, but so long as there are human beings, songs and poetry can continue. If my poetry aims to achieve anything, it’s to deliver people from the limited ways in which they see and feel.’

Jim Morrison, Wilderness Vol. I (Vintage Books, 1989) p. 2

Words dissemble

Words be quick

Words resemble walking sticks

Plant them they will grow

Watch them waver so

I’ll always be a word man

Better then a bird man

From ‘Curses, Invocations’, An American Prayer

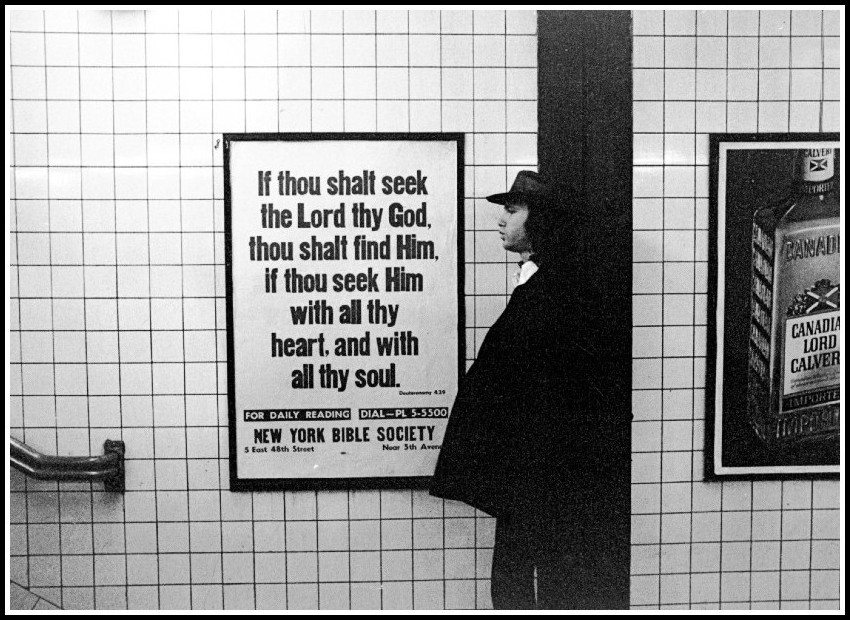

Jim Morrison between Whisky and the Word in the NYC Subway | Photo: Paul Ferrara

JIM MORRISON: THREE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL POEMS

Jim Morrison, Wilderness I (Vintage Books, 1989) p. 202, 207-08

I

I am a Scot, or so

I’m told. Really

the heir of Mystery

Christians

Snake in the Glen

The child of a

Military family…

I rebelled against church

after phases of

fervor

I curried favor in school

& attack’d the teachers

I was given a

desk in the corner

I was a fool

&

the smartest kid

in class

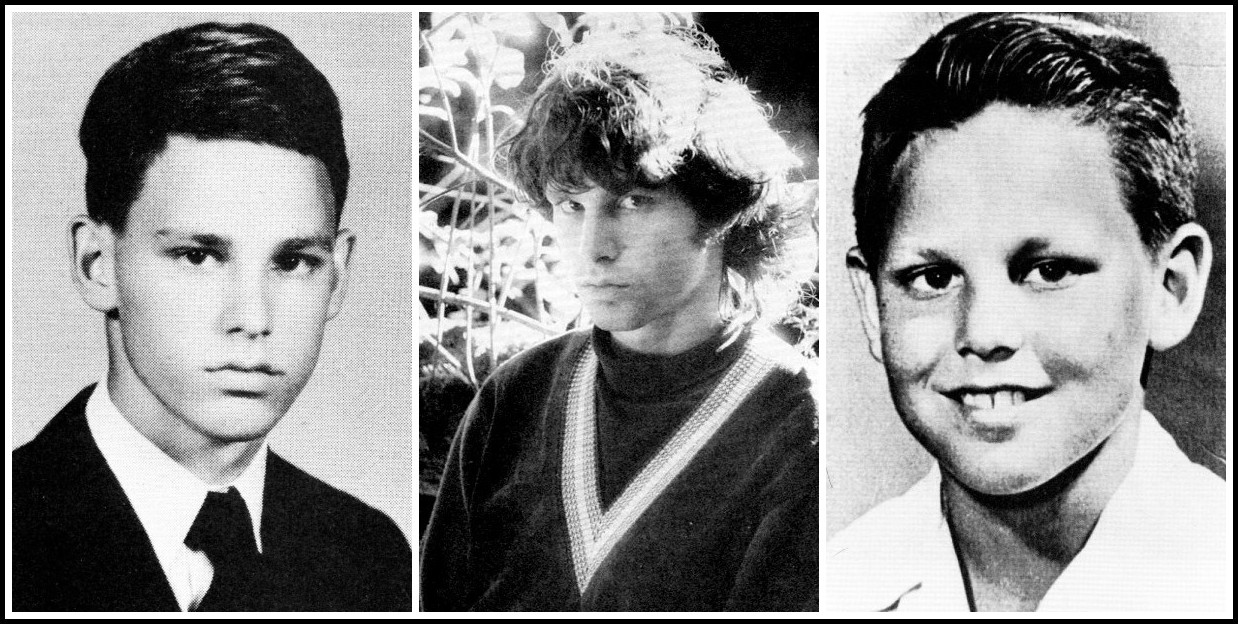

Jim Morrison | Photos: George Washington High School, Virginia | Robert Klein | Junior High School

II

A natural leader, a poet,

a Shaman, w/the

soul of a clown.

What am I doing

in the Bull Ring

Arena

Every public figure

running for Leader

Spectators at the Tomb

—riot watchers

Fear of Eyes

Assassination

Being drunk is a good disguise.

I drink so I

Can talk to assholes.

This includes me.

Jim Morrison | Photo: Andrew Kent

III

The horror of business

The Problem of Money

guilt

do I deserve it?

The Meeting

Rid of Managers & agents

After 4 years I’m left w/a

mind like a fuzzy hammer

regret for wasted nights

& wasted years

I pissed it all away

American Music

Jim Morrison | Photos: Ed Caraeff | Araldo di Crollalanza

JIM MORRISON & ARTHUR RIMBAUD: LETTER TO WALLACE FOWLIE

Wallace Fowlie, Rimbaud and Jim Morrison: The Rebel as Poet (Duke University Press, 1994) p. 15

Dear Wallace Fowlie,

Just wanted to say thanks for doing the Rimbaud translation. I needed it because I don’t read French that easily. I am a rock singer and your book travels around with me.

Jim Morrison

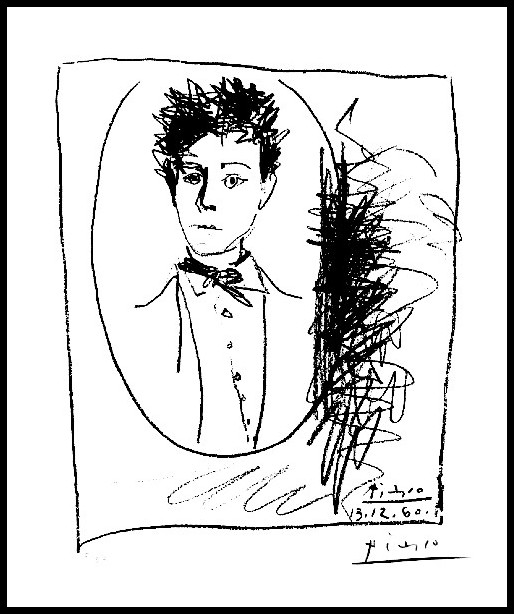

P.S. The Picasso drawing of Rimbaud on the cover is great!

Picasso, Rimbaud, 1960

JIM MORRISON & ARTHUR RIMBAUD: ‘EVENING PRAYER’

‘Evening Prayer’ is one of Rimbaud’s strongest poems, and one Morrison especially liked.

Wallace Fowlie, Rimbaud and Jim Morrison: The Rebel As Poet (Duke University Press, 1994) p. 16

ORAISON DU SOIR

Arthur Rimbaud

Je vis assis, tel qu’un ange aux mains d’un barbier,

Empoignant une chope à fortes cannelures,

L’hypogastre et le col cambrés, une Gambier

Aux dents, sous l’air gonflé d’impalpables voilures.

Tels que les excréments chauds d’un vieux colombier,

Mille Rêves en moi font de douces brûlures:

Puis par instants mon cœur triste est comme un aubier

Qu’ensanglante l’or jeune et sombre des coulures.

Puis, quand j’ai ravalé mes rêves avec soin,

Je me tourne, ayant bu trente ou quarante chopes,

Et me recueille, pour lâcher l’âcre besoin:

Doux comme le Seigneur du cèdre et des hysopes,

Je pisse vers les cieux bruns très haut et très loin,

Avec l’assentiment des grands héliotropes.

EVENING PRAYER

Artur Rimbaud | Wyatt Mason

I live my life sitting, like an angel in a barber’s chair,

A big fluted beer mug in my hand, neck and hypogastrus

Arched, a cheap Gambier pipe between my teeth,

And the air above me swollen with sails of smoke.

Like steaming droppings in an old dovecote

A thousand Dreams within me gently burn:

And at times my sad heart is like sapwood

Bleeding dark yellow gold where a branch is torn.

Then, when I’ve methodically drowned my dreams

With thirty or forty beers, I pull myself together

And release my bitter need:

Sweet as the Lord of Hyssop and Cedar,

I piss into the brown sky, far and wide,

Heliotropes blessing me below.

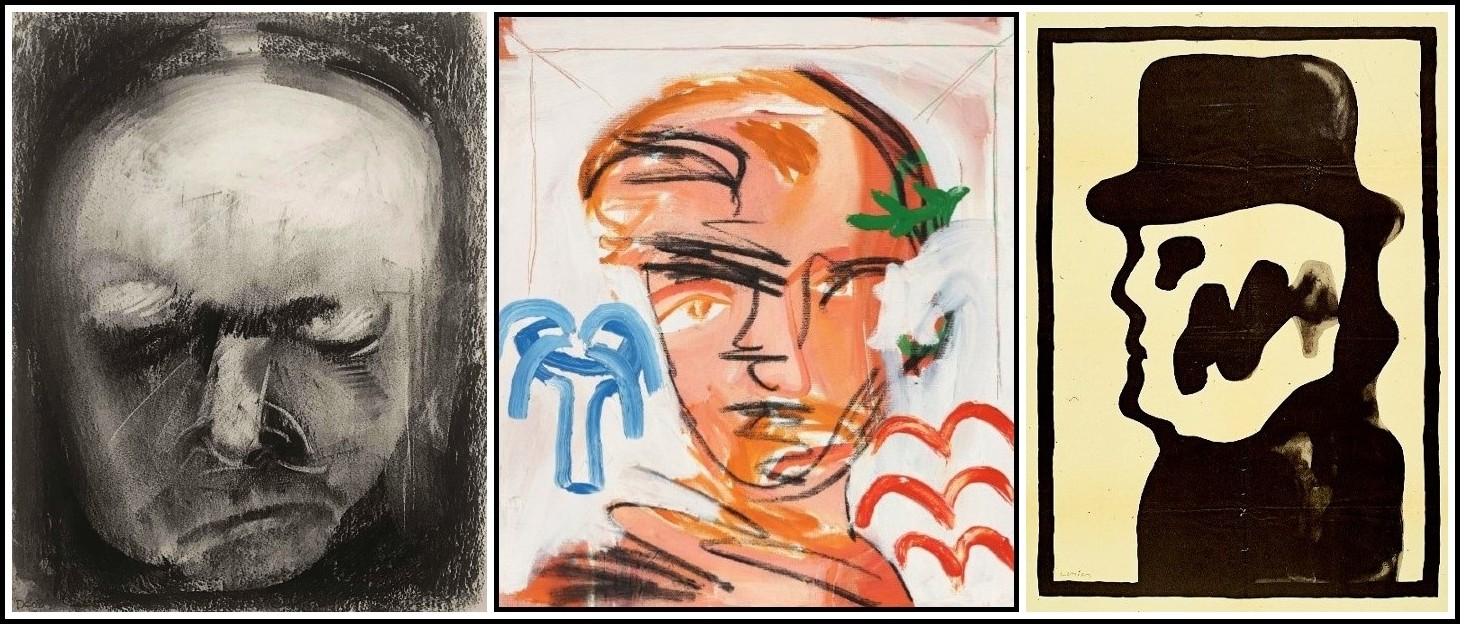

Sidney Nolan, Young Rimbaud, 1982 | Yale Joel, Jim Morrison, 1968

JIM MORRISON & WILLIAM BLAKE

AUGURIES OF INNOCENCE

William Blake

Every night and every morn

Some to misery are born

Every morn and every night

Some are born to sweet delight

Some are born to sweet delight

Some are born to endless night

We are led to believe a lie

When we see not through the eye

Which was born in a night to perish in a night

When the soul slept in beams of light

God appears and God is light

To those poor souls who dwell in night

But does a human form display

To those who dwell in realms of day

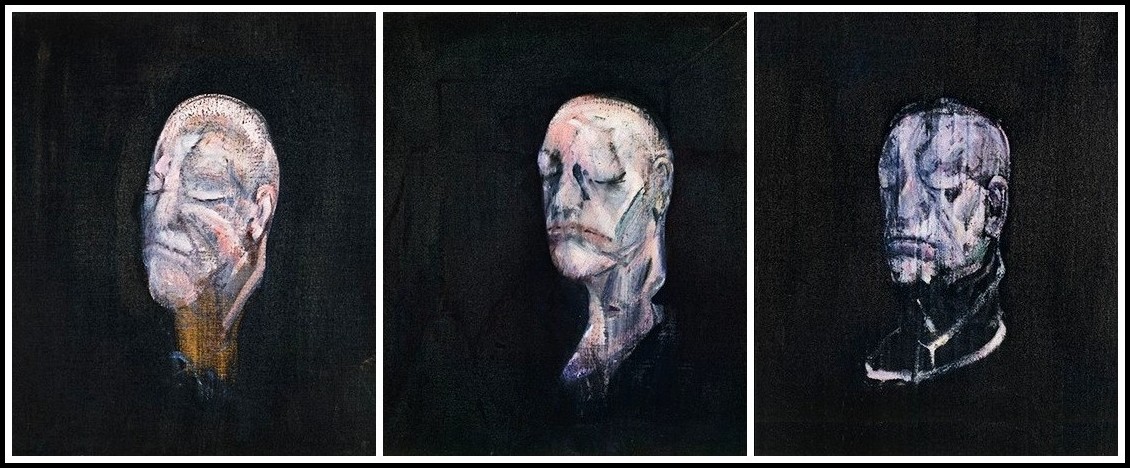

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait I, II, III (after the Life Mask of William Blake), 1955

END OF THE NIGHT

Jim Morrison | The Doors

Take the highway to the end of the night

End of the night, end of the night

Take a journey to the bright midnight

End of the night, end of the night

Realms of bliss, realms of light

Some are born to sweet delight

Some are born to sweet delight

Some are born to the endless night

End of the night, end of the night

Realms of bliss, realms of light

Some are born to sweet delight

Some are born to sweet delight

Some are born to the endless night

End of the night, end of the night

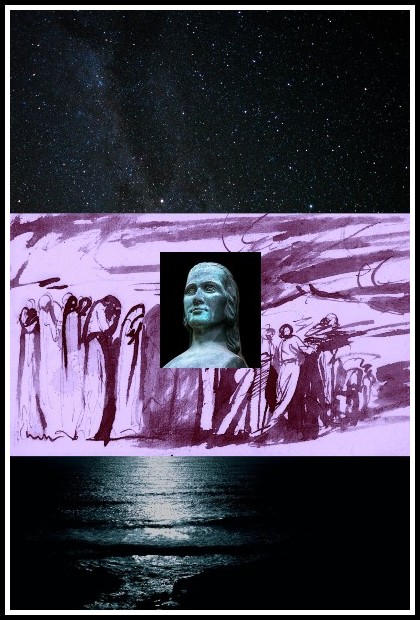

Photos: Jim Morrison by Joel Brodsky | Lukas Robertson | Raphael Nogueira

MARTIN HEIDEGGER: WHAT ARE POETS FOR?

‘… and what are poets for in a destitute time?’ asks Hölderlin’s elegy ‘Bread and Wine.’ We hardly understand the question today. How, then, shall we grasp the answer that Hölderlin gives? The word ‘time’ here means the era to which we ourselves still belong. For Hölderlin’s historical experience, the appearance and sacrificial death of Christ mark the beginning of the end of the day of the gods. Night is falling. Ever since the ‘united three’—Herakles, Dionysus, and Christ—have left the world, the evening of the world’s age has been declining toward its night. The world’s night is spreading its darkness. If a poet is a ‘poet in a destitute time’ then only his poetry answers the question to what end he is a poet, whither his song is bound, where the poet belongs in the destiny of the world’s night. That destiny decides what remains fateful within this poetry.

Martin Heidegger, ‘What Are Poets For?’ in Poetry, Language, Thought, tr. Albert Hofstadter (NY: Harper Colophon, 1975) p. 91 (first two paragraphs) and p. 142 (last paragraph)

BREAD AND WINE

Hölderlin | Michael Hamburger

But frenzy,

Wandering, helps, like sleep;

Night and distress make us strong

Till in that cradle of steel heroes enough have been fostered,

Hearts in strength can match heavenly strength as before.

Thundering then they come.

But meanwhile too often I think it’s

Better to sleep than to be friendless as we are, alone,

Always waiting, and what to do or to say in the meantime

I don’t know, and what are poets for in a destitute time?

But they are, you say, like those holy ones,

Priests of the wine-god who in holy night

Roamed from one place to the next.

Friedrich Hölderlin, Selected Poems and Fragments, tr. Michael Hamburger (Penguin Books, 1994) p. 157. Translation modified, second stanza, fifth line: ‘and who wants poets at all in lean years?’ changed to ‘and what are poets for in a destitute time?’.

Hölderlin | The Damned | L. Robertson | R. Nogueira

GREIL MARCUS ON ‘THE END’

Abbreviated from Greil Marcus, The Doors (NY: Public Affairs, 2011) pp. 25-29

Early on, Robby Krieger developed a way of saying, in a very few, quiet, spaced notes on his guitar, that something was about to happen. He could make you draw your breath. It happened first with ‘The End’. In the studio the song unwinds over nearly twelve minutes; those first notes tell you to suspend any expectations of how long this is going to last. A tambourine shivers off to the side of the sound. In ‘Take It as It Comes’, the song before ‘The End’, the band was both light on its feet and relentless, and what was coming felt dark, hard, irresistible—a test, not anything you could expect. ‘The End’ was the test. Two minutes in, Krieger plays an atonal figure against a steady count, Ray Manzarek shifts quietly behind him, a green river in the cave of the song, and—a minute, a minute and a half has passed, but there’s no sense of time passing—John Densmore hits his drums off the beat, louder each time, fracturing the sound, the sound so big you can see an avalanche of drums burying everyone else. This is a repeating moment; events like this occur across the span of ‘The End.’ All through the piece, there will be incidents when the performance feels as if it’s about to tear itself to pieces. It’s a question of rhythm. The furious, impossibly sustained assault that will steer the song to its end, a syncopation that swirls on its own momentum, each musician called upon not just to match the pace of the others but to draw his own pictures inside the maelstrom.

Tommaso Fattovitch, Gulch, 2021 (detail)

There were exciting pauses in ‘Take It as It Comes,’ when the band pulled back from itself, letting the song loose, letting it tell them where to take it next. Instruments dropped out, but a pulse always held. And throughout ‘The End’, until that final surge, everything seems tentative, uncertain, unclear; that’s the source of the song’s power, its all-encompassing embrace of darkness, gloom, and dread, and it’s this insistence on the uncertain, on working without a ground, that makes the performance. Morrison’s words have the feel of phrases made up on the spot to fit or break the rhythms taking shape around him: the languid, sleepy ‘The west is the best’ followed by the staccato jump in the way the last five words of ‘Get here—and we’ll do the rest’ pull the first two words after them like a weight pulling a house off a cliff. There is the drifting chase after a blue bus, a chase that is a matter of someone walking slowly, deliberately, no matter how fast the bus is going, knowing that sooner or later he’ll catch it and climb on.

Tommaso Fattovitch, Gulch, 2021 (detail)

Morrison’s voice in the slides in the music that seem to matter most—at the beginning and the end, where ‘my only friend’ is brought into the song and then banished, so the singer can contemplate the perfection of his own isolation, his own renunciations, his own beauty—is full, creamy, a deep well. You could drop a coin into the pool of this voice and never hear the splash. As the voice opens over words or syllables—’friend,’ ‘only,’ ‘die’—the words change shape, gliding out into the empty spaces in the sound. The way Morrison sings the plain flatness of ‘my only friend’ instantly takes ‘the end’ down to a plane of ordinary life, lets the listener into the song, and sets the words free to find their traveling companions. No element in the music seems to anticipate any other, to call any other forth; the performance is a dance around a fire, with the pace determined by the flickers, which can’t be anticipated, that are never the same—not until the set piece in the center, when the singer says he wants to kill his father and fuck his mother. The singer goes quietly into his sister’s room, then into his brother’s room, he could leave them both dead, he could just be making sure they’re asleep, but when he gets to his father and his mother, you realize you’ve heard this story before.

Tommaso Fattovitch, Gulch, 2021 (detail)

Minutes later, with the music gathering itself for its final charge, the real drama takes place. Krieger, Manzarek, and Densmore are pushing for a centrifugal momentum that will create its own Big Bang, until each piece flies away from the other; Morrison, his one-legged, spread-eagled stage dance now playing out on his tongue, is the controlling rhythmic force. ‘Fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck,’ he snaps, snarls, talking into a mirror, testing the word for its feel in his mouth, finding the same brittle, syncopated click with which Krieger opened the theme, the word ‘fuck’ buried but viscerally changing shape each time he spits it out. Everything slows down again, and the song returns to the beckoning, the foreshadowing, of its first moments. Wherever it was you started from, you have traveled somewhere else, and no time at all has passed.

Tommaso Fattovitch, Gulch, 2021 (detail)

THE END

Jim Morrison | The Doors

This is the end, beautiful friend

This is the end, my only friend the end

Of our elaborate plans the end

Of everything that stands the end

No safety or surprise the end

I’ll never look into your eyes again

Can you picture what will be

So limitless and free

Desperately in need of some stranger’s hand

In a desperate land

Lost in a Roman wilderness of pain

And all the children are insane

All the children are insane

Waiting for the summer rain

There’s danger on the edge of town

Ride the king’s highway, baby

Weird scenes inside the gold mine

Ride the highway west, baby

Tommaso Fattovitch, Passed Me By, 2021 (detail)

Ride the snake, ride the snake

To the lake, the ancient lake, baby

The snake is long, seven miles

Ride the snake, he’s old

And his skin is cold

The West is the best, the West is the best

Get here and we’ll do the rest

The blue bus is calling us

The blue bus is calling us

Driver, where you taking us?

The killer awoke before dawn

He put his boots on

He took a face from the ancient gallery

And he walked on down the hall

He went into the room where his sister lived

And then he paid a visit to his brother

And then he, he walked on down the hall

And he came to a door

And he looked inside

Father?

Yes, son?

I want to kill you

Mother, I want to…

Tommaso Fattovitch, Passed Me By, 2021 (detail)

Come on, baby, take a chance with us

Come on, baby, take a chance with us

Come on, baby, take a chance with us

And meet me at the back of the blue bus

Blue bus, blue bus, come on, yeah

This is the end, beautiful friend

This is the end, my only friend, the end

It hurts to set you free

But you’ll never follow me

The end of laughter and soft lies

The end of nights we tried to die

This is the end

Tommaso Fattovitch, Passed Me By, 2021 (detail)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments

2 thoughts on “Jim Morrison, Poet”

This is a marvelous site, thank you!

Your readers might be interested to know where Jim got the words, “not to touch the earth, not to see the sun”; they will find it in Frazer’s The Golden Bough, Macmillan Papermac p.54, ch. 9, and the words refer to human deities being carried always so as not to touch the earth, and not being able to be outside, not to see the sun. Now as for Waiting for the Sun, Jim picked that up from the Popul Vuh, the sacred book of the Quiche Maya, English version by Delia Goetz and Sylvanus G. Morley, University of Oklahoma Press. Whereas T.S. Eliot put the Wasteland out with all the literary references at the back to impress the uninitiated, Morrison, in modesty, left it to the reader’s intelligence to figure his work out, at whatever level gave them meaning. He was indeed a voracious and eclectic reader. This information would enlighten some of the academic theses being written about his work which to date only scratch the surface.