Background: Paul Klee, Highway and Byways, 1929 (detail)

MILES DAVIS QUINTET, 1965-68

Ron Carter, 2009

Photo: La Bella Strings

Tony Williams, 1965

Photo: Francis Wolff

Miles Davis, 1967

Photo: Lee Friedlander

Herbie Hancock, 1967

Photo: Francis Wolff

Wayne Shorter, 1996

Photo: Eric Draper

Paul Klee

Highway and Byways, 1929

If the genius of jazz lies in spontaneous collective interplay, what becomes of the notion of ‘art and individuality’? Wayne Shorter (tenor saxophone), Herbie Hancock (piano), Tony Williams (drums) and Ron carter (bass) were, it can be argued (see, for example, Robert Walser), more technically proficient on their instrument than Miles was on his (trumpet). Yet these four outstanding musicians all submitted their compositions to Miles and deferred to his individual vision as, collectively, they ‘re-composed’ them. Why? Simply because Miles, in his individuality, encouraged them all to think and play ‘outside-the-box’, not in a jamboree of ‘free jazz’ (which elicited nothing but scorn from Miles), but in pursuit of Miles’ musical conceptions.

Claude Monet, Agapanathus, 1914

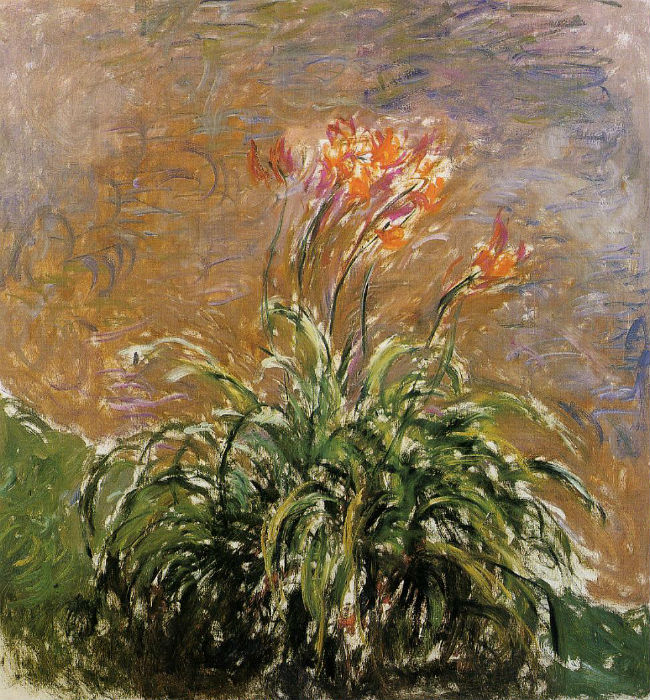

Miles and Monet: As the improvisations float on the chords, the brushstrokes conjure elusive colours.

If a leader is one who ‘gets things done through other people’, this implies, firstly, that he has earned their trust, and secondly, that they have ‘bought into’ his vision. Miles, like all artists who appear to ‘impose’ their individuality, had utter self-conviction: He never doubted his ability to discriminate, to choose according to only the touchstone of his taste. Artists with less strongly affirmed individuality stick with the safety of convention; they often cultivate ‘technique’ in an attempt to stand out. In this quintet, Miles was the lesser instrumentalist but the greater conceptualist, and the other musicians were the first to recognize the beauty of the music that would emerge by deferring to Miles’ vision.

Claude Monet, Hamerocallis, 1914

Each time I listen to the quintet’s albums, I am struck by their freshness, timelessness and sense of excitement, and I marvel at how such collectively-created music bears the stamp of one man’s individuality. How to describe it, that individuality? Words that immediately come to mind are pride and dignity, then fierce poetry, a taste for the oblique, and something the French call ‘pudeur’, meaning that however much is given, however brilliant the gift, there remain endless reserves of interiority. And then there are the paradoxes: dynamic stillness, lush restraint, play and experimentation with seriousness and purpose. Dark, elegant, daring; defiant, pure, uncompromising. All these words can be boiled down to one: Miles.

Claude Monet, Irises, 1914

For those who come to jazz from rock culture, think of John Lennon’s limited instrumental prowess, then remember he wrote ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ and ‘A Day in the Life’. Or think of David Bowie, whose disdain for repetition, whose restless creativity, opened up new directions in rock music. Or think of Pink Floyd, who conceived of each album not as a collection of songs but as an organic whole. And if it’s from classical music that you come to jazz, think of the spare eloquence of Anton Webern, the subtleties and refinement of Debussy, or the sensuousness and verve of Richard Strauss. And if you come to jazz from opera, well who else but Wagner? But enough of such seduction—just listen to the music, and let Miles’ second great quintet reveal to you the details of the sunset, the sound of one hand clapping, and the unheard cry among the angelic orders.

KEITH WATERS on the STUDIO RECORDINGS of the MILES DAVIS QUINTET, 1965-68

Posted by kind permission of Keith Waters, Professor of Music at the College of Music, University of Colorado at Boulder

Source: Keith Waters, The Studio Recordings of the Miles Davis Quintet, 1965-68 (OUP USA, 2011)

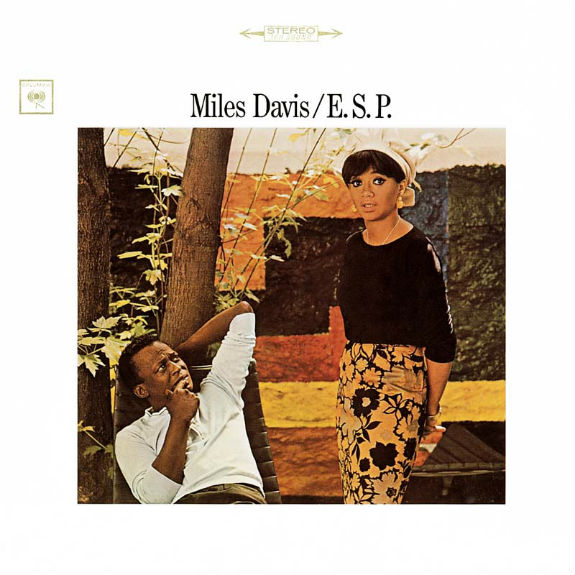

E.S.P. (Recorded 20–22 January 1965)

The melody to ‘E.S.P.’ is notable for its foregrounding of the perfect fourth interval. It becomes the central focus of the composition’s melody, as it was with Shorter’s ‘Witch Hunt’ (Speak No Evil, 1964), which similarly arpeggiates perfect fourths. This brings to the melodic dimension what was becoming a distinct feature of harmonic accompaniment in the 1960s, most notably pianist McCoy Tyner’s fourth-based comping with the John Coltrane Quartet. Later Shorter compositions recorded by Davis’s second quintet, such as ‘Orbits’ and ‘Nefertiti’, project the interval in more subtle ways. Its bald use in ‘E.S.P.’ functions, it would seem, as a token of mid-1960s modernism.

Various quintet members described working processes in the studio. Their descriptions highlighted Davis’s role in suggesting changes to compositions brought in by the sidemen. Hancock noted: ‘If anybody brings a composition in to Miles, he breaks it down to a skeletal form in such a way that each person in the group can start putting the pieces back together. You still have the essence of the original composition, but you create a new composition on that essence.’ Davis himself discussed this in an interview: ‘Well, Herbie, Wayne or Tony will write something, then I’ll take it and spread it out or space it, or add some more chords, or change a couple of phrases, or write a bass line to it, or change the tempo of it, and that’s the way we record. If it’s in 4/4 time, I might change it to 3/4, 6/8 or 5/4.’ Hancock described how Davis applied this process to Ron Carter’s composition ‘Eighty-One’: ‘Miles took the first two bars of melody notes and squished them all together, and he took out other areas to leave a big space that only the rhythm section would play. To me, it sounded like getting to the essence of the composition.’

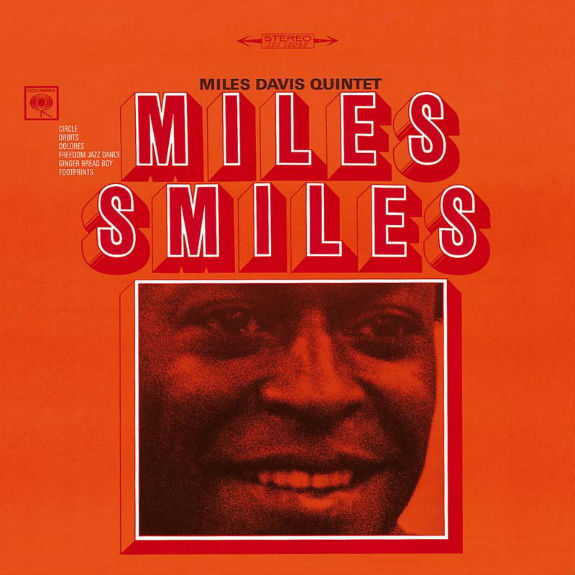

Miles Smiles (Recorded October 24–October 25, 1966)

In comparison with E.S.P., the recorded sound of Miles Smiles was decidedly richer, with Davis placed significantly higher in the mix. And for the entire quintet, the music moved significantly beyond that of E.S.P. The quintet further developed its celebrated sense of airy openness and space. This is the first Davis studio recording on which Hancock stops comping behind entire solos, and his own solos on those compositions (‘Orbits’, ‘Dolores’, ‘Ginger Bread Boy’) avoid left-hand accompanimental chords. The album offers further challenges to chorus structure, particularly through the use of ‘time, no changes’ on compositions such as ‘Orbits’. ‘Circle’ makes seamless use of an additive form by inserting additional 4-bar sections during the solos. Many of the solos concentrate on motivic improvisation arising from melodic paraphrase. On ‘Ginger Bread Boy’ and ‘Footprints’, the group rethinks conventional attitudes toward the 12-bar blues. With ‘Ginger Bread Boy’ the group transforms Jimmy Heath’s 12-bar blues into a 16-bar form. ‘Footprints’ refits a 12-bar minor blues with an unconventional harmonic turnaround, subjecting it to metric modulation that shifts the 6/4 meter into 4/4. For many musicians and critics, Miles Smiles remains the group’s quintessential studio recording, one that best represents the effortless negotiation between the traditional and the experimental.

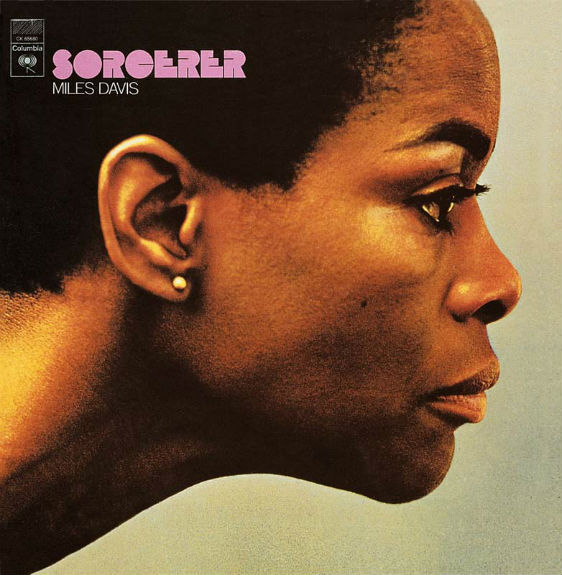

Sorcerer (Recorded May 16–24, 1967)

Herbie Hancock wrote the title track, ‘The Sorcerer’, and dedicated it to Davis, noting ‘Miles is a sorcerer. His whole attitude, the way he is, is kind of mysterious. His music sounds like witchcraft. There are times I don’t know where his music comes from. It doesn’t sound like he’s doing it. It sounds like it’s coming from somewhere else’. Wayne Shorter concurred by saying, ‘It was as if Miles wasn’t even playing a trumpet. His instrument was more like a spoken dialogue or like he was a painter using a brush or a sculptor using a hammer and chisel’. On the one hand, the album title and its title track show the quintet members perpetuating the mystique surrounding Davis’s persona. On the other hand, Hancock’s and Shorter’s comments show the players bewitched by the ways in which Davis transcended his instrument. Certainly Sorcerer reveals Davis’s sound and motivic sense fully crystallized, allowing a vast palette of expressive timbres and improvised motives played with such unerring confidence that—even when they do not reflect the underlying harmony—their execution heightens their sense of inevitability.

In contrast to the earlier Miles Smiles, Sorcerer remains more detached from the hard bop tradition by largely abandoning the walking bass swing feels heard on the earlier recording. ‘Vonetta’ indicates further developments in Shorter’s harmonic vocabulary in the context of a circular tune. On ‘Masqualero’ the quintet molded the slow-moving harmonic progression, highlighted by the phrygian orientation, into a deeply dramatic performance. Davis’s and Hancock’s solos on ‘Prince of Darkness’ show the improvisers firmly committed to motivic improvisation, while still offering significant challenges to the underlying regularity of the 16-bar single section form. ‘Pee Wee’, an unusual 21-bar form, supported a melodic structure and harmonic structure frequently operating independently of one another. And the two takes to ‘Limbo’ show remarkably different approaches to the same composition: the alternate take removed a number of harmonies and maintained the underlying triple meter; the released track involved a more intricate harmonic progression, and shifted to 4/4 as the solos began.

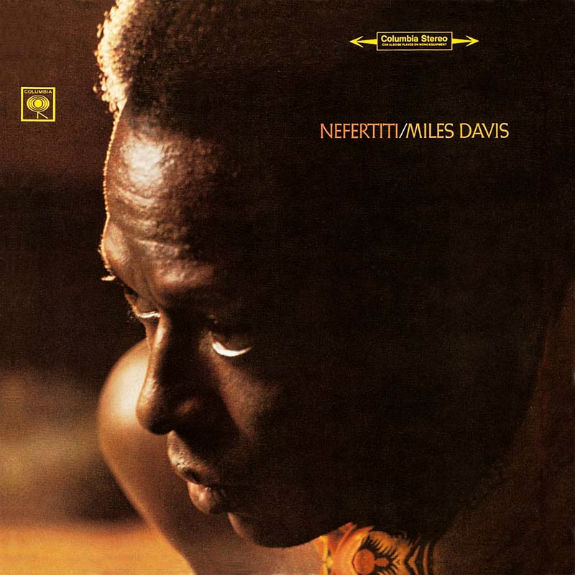

Nefertiti (Recorded June 7, 22-23 and July 19, 1967)

Did the title track to Nefertiti mark a watershed moment for the second quintet? The group took the decisive and unusual step of performing ‘Nefertiti’ without improvisations by trumpet, saxophone and piano. Instead, the recording consists of repeated statements of the melody, with shifting accompaniment provided by the rhythm section, effectively reversing the standard roles for horns and rhythm section. For many reasons—the absence of standard horn/piano improvisations, the floating melody consisting of three related phrases, the harmonic progression, the mercurial rhythm section accompaniment—Shorter’s composition ‘Nefertiti’ represented for many an important point of departure. For pianist Josef Zawinul, ‘Nefertiti’ was emblematic of the ‘new thinking’. Michelle Mercer writes ‘‘Nefertiti’ was the harbinger of a new period for Miles, one in which improvised solos became secondary to mood and fragmented riffs.’

Yet it may be more accurate to consider the quintet’s decision to record ‘Nefertiti’ only with repeated statements of melody as evolving out of a continuing practice, one that thrust compositional melody further into the foreground. On earlier recordings the quintet began returning to the composition’s melody between and within the improvisations (‘Freedom Jazz Dance’, ‘Vonetta’, ‘The Sorcerer’ and ‘Prince of Darkness’). This posed an alternative to standard chorus structure, which typically relies on the compositional melody stated merely at the beginning and the end of the performance. However, with ‘Nefertiti’, the quintet takes the decisive step by making statements of the melody the central event of the composition, replacing standard improvisation by horns and piano.

Elsewhere Nefertiti features unusual techniques. ‘Fall’ also blurred conventional distinctions between melody and improvisation: it begins with the trumpet improvisation and ends with the bass improvisation, and only fragments of the melody are heard during those two improvisations. The improvisations in ‘Riot’ move down by half step with each new solo. Yet the quintet also returns to some improvisational and accompanimental strategies heard earlier on Miles Smiles but largely absent from Sorcerer. The group applies the technique of ‘time, no changes’ in the context of 4/4 walking bass on ‘Madness’ and ‘Hand Jive.’

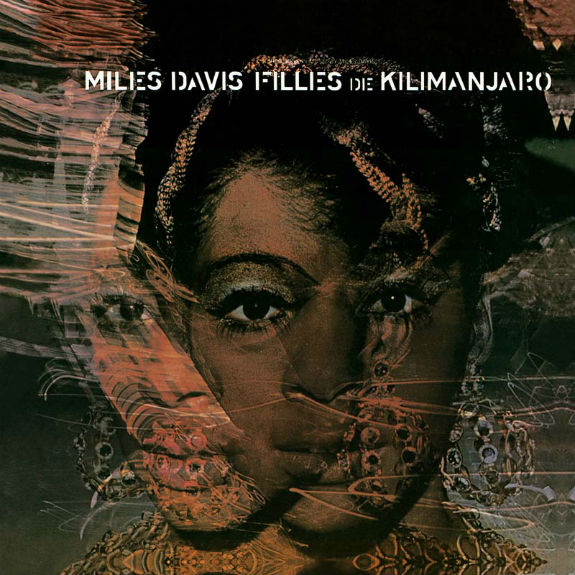

Miles in the Sky (Recorded January 16 and May 15–17, 1968) and Filles de Kilimanjaro (Recorded June 19–21 and September 24, 1968)

Miles in the Sky and Filles de Kilimanjaro differed qualitatively from the earlier recordings, and marked an important turning point for the group. Some of the differences were patent. For example, the move to electric piano and electric bass, the use of single extended tonal centers for improvisation, and the importation of rock-based straight-eighth rhythms all adumbrated an imminent shift to jazz-rock fusion. But there were subtler but no less drastic changes on these final quintet recordings. One change involved retooling and rethinking conventional attitudes toward chorus structure and jazz composition. And this took place as Davis became the primary composer, writing or co-writing six of the ten compositions on these last two albums.

It is both tempting and necessary to acknowledge Miles in the Sky and Filles de Kilimanjaro as significant predecessors for Davis’s later fusion work, with the use of rock rhythms, pedal point improvisation, and a harmonic language somewhat sparer than earlier quintet recordings. The fusion of jazz with R&B, gospel, and rock was already firmly in place by the early 1960s, appearing in funky jazz works such as Lee Morgan’s ‘Sidewinder’ and Herbie Hancock’s ‘Watermelon Man.’ But a view of these two Davis recordings solely as transitional, emerging between the twilight of postbop jazz and the dawn of fusion—or, alternatively, in light of the jazz avant-garde—does not address substantively their achievement and novelty. Likely it was these recordings that Hancock described when he said, ‘We were always trying to create something new. It became more and more difficult. Like trying to make conversation never using any words you used before’.

Certainly much more involved compositional structures appear on these recordings. ‘Stuff’ begins as a 40-bar form, whose later head statements expand and contract the internal sections, and whose melodic fragments return altered with each reappearance. ‘Tout de Suite’ is an elaborate 70-bar form. ‘Filles de Kilimanjaro’ is a series of seven melodic ideas, several of which are fragmentary, many of which appear in different metric identities with each restatement. These compositions re-evaluate the relationship of compositional melody to improvisations: multiple head statements postpone the improvisation until three or four minutes into the recording—with ‘Stuff,’ improvisations are withheld until after nearly six minutes of head statements. For both ‘Stuff’ and ‘Filles de Kilimanjaro’, the alterations made to successive melodic statements create a sense of shifting perspective upon recurring melodic objects.

Davis’s ‘Country Son’ exhibited yet another challenge to conventional notions of jazz composition by removing melody from the composition, which consisted of three contrasting sections, without any overt melody head statements. The group determined the length of two of those three sections spontaneously during performance. And the head to ‘Paraphernalia’ used melodic statements with intervening sections of freely determined length played by the rhythm section. These two compositions maintain an elastic harmonic framework liberated from a consistent underlying hypermeter. With the self-imposed challenge of flexible harmonic rhythm, the quintet relies on spontaneous musical cues to advance the harmonic progressions.

For anyone who shares my view that the studio albums recorded by Miles Davis in his ‘second great quintet’ rank among the finest achievements in all of music, this book is a delight from cover to cover. Keith Waters brings his musicological expertise and extensive jazz culture to make the ineffable comprehensible, while preserving its mystery. His analyses, in other words, serve a greater appreciation of the music. Be aware, however, that the book only reveals the fullness of its riches to those well-versed in music theory.

Click on the image to go to the OUP page on the book.

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2017 | All rights reserved

Comments

2 thoughts on “Miles Davis Quintet, 1965-68”

What a fine survey! I believe this is among the very best jazz ever played on earth. I have owned the complete boxed set Live at the Plugged Nickel for more than 20 years and it continues to reveal new things every night, every set.

I’ll return to this article a few times. Lots to enjoy, mull over and appreciate.