Last Tango in Paris

Bernardo Bertolucci, 1972

BERNARDO BERTOLUCCI ON ‘LAST TANGO IN PARIS’

Interview by Gideon Bachmann, 1973

From Bernardo Bertolucci: Interviews edited by F.S. Gerard, T.J. Kline & B. Sklarew (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2000; pp. 92-99)

Originally, I wanted to make a film about a couple, about a relationship between two people. As I began to work and felt the film taking shape, I realized I was making a film about solitude. I believe that this is its most profound content: solitude.

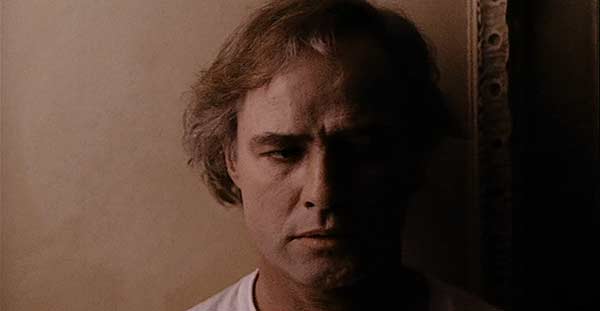

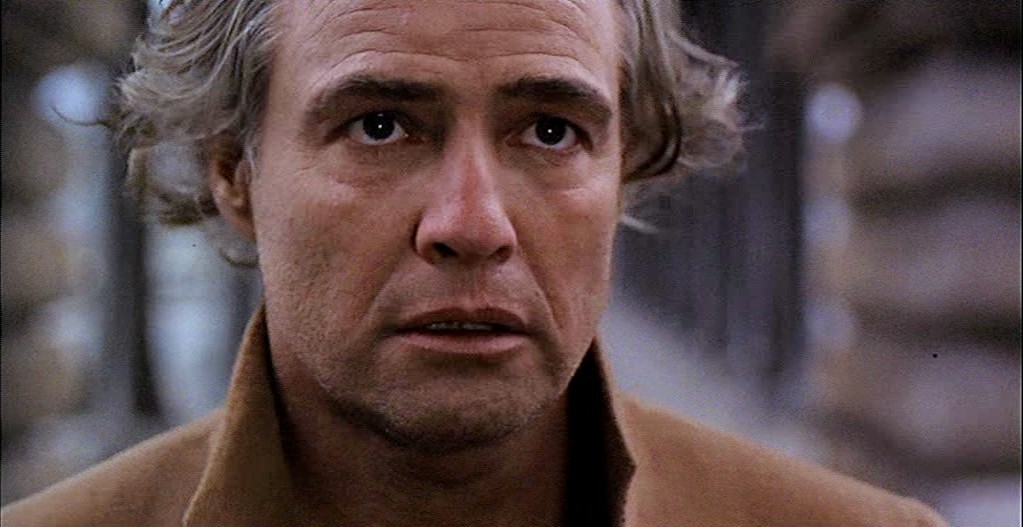

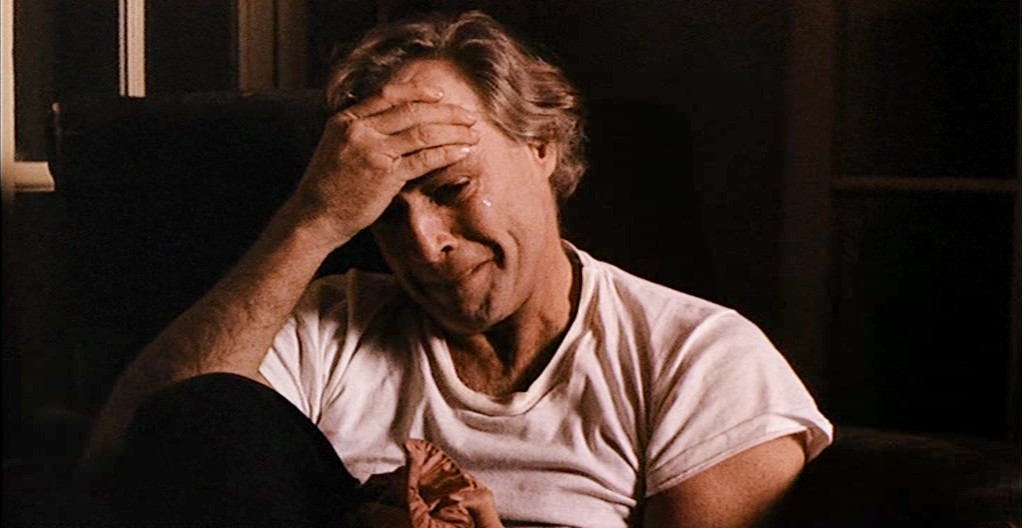

Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

The encounter of Paul and Jeanne ends up being an encounter of forces pulling in different directions; the kind of encounter of forces which exists at the base of all political clashes. Brando, initially rather mysterious, manages to upset the girl’s bourgeois lifestyle, at least at the beginning, by force of his mystery and obvious search for authenticity. His way of making love to her is practically didactic. Didactic in the sense that he seeks the roots of human behavior in that moment, the moment after his wife’s suicide, when he has reached a peak and a dead end at the same time. He believes that he must seek absolute authenticity in a relationship, and this, I feel, gives the encounter its political sense.

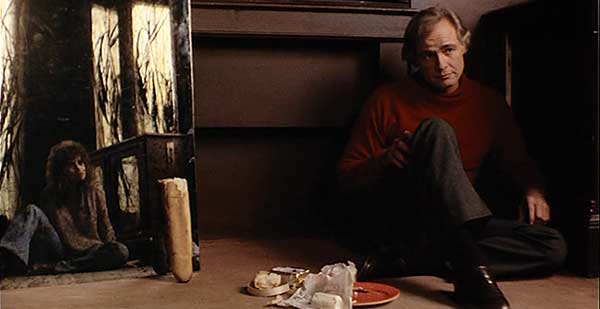

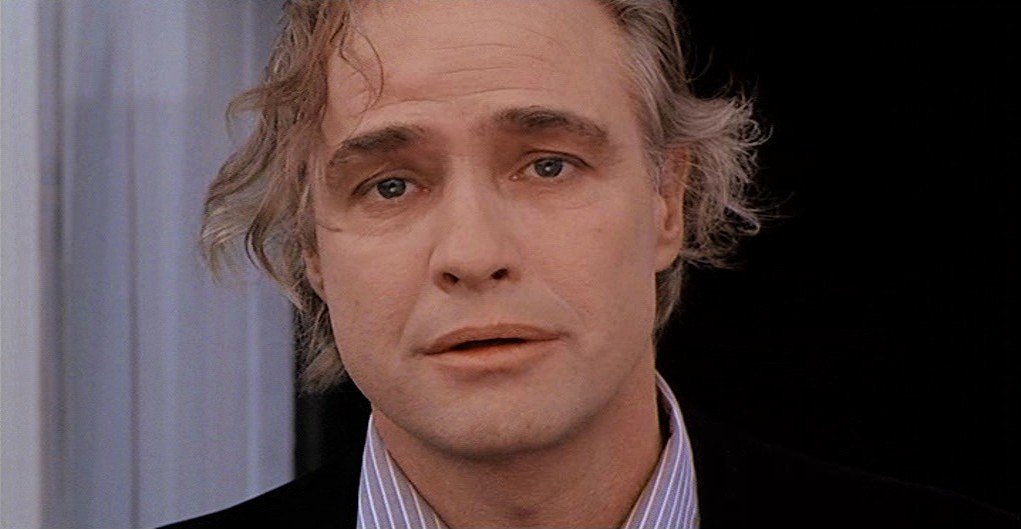

Maria Schneider & Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

I still feel I am looking for the very specific light that is typical and expressive of every feeling and of every epoch, and I still seek the very specific way of representing how time passes—that particular, psychological passage of time that gives a film its style. Perhaps it is a matter of percorso, of how a man moves through time, in the historical and in the practical, daily sense. That, in fact, is what holds Tango together, as I see it now: Brando’s retreat from being a man of 45 back to being an adolescent and finally dying like a foetus.

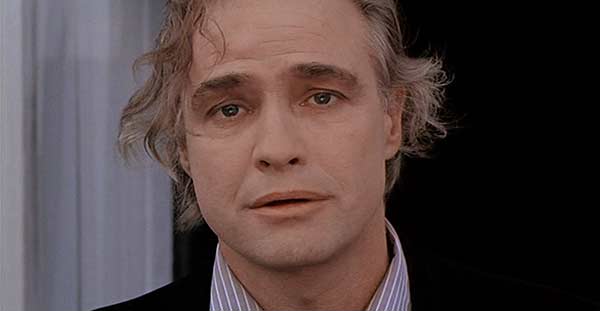

Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

At the beginning of the film he is super-virile, desperate but determined in his despair. Look at how he fucks the girl the first time. But slowly he almost loses his virility. At a certain point he makes the girl sodomize him: going backwards, he has arrived at the anal stage. Let’s say, the sadistic‑anal stage. Then he goes back even further and arrives in the womb of Paris, dying with Mother Paris all around him, her rooftops, TV‑aerials, her grey, grabbing anonymity.

Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

There are many ways of getting over that kind of pain, perversion and sex are obvious ones. Sex is very close to death in feeling.

Maria Schneider & Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

I didn’t make an erotic film, only a film about eroticism. In any case, you cannot separate ‘erotic’ behavior from the rest of human action. It is almost always like this, that things are ‘erotic’ only before relationships develop; the strongest erotic moments in a relationship are always at the beginning, since relationships are born from animal instincts. But every sexual relationship is condemned. It is condemned to lose its purity, its animal nature; sex becomes an instrument for saying other things. In the film, Paul and Jeanne try to maintain this purity by avoiding psychological and romantic entanglement, by not telling each other who they are, etc., but it proves impossible, since dependencies of various types develop.

Maria Schneider & Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

Every relationship is condemned to change. Perhaps it can improve, but generally it deteriorates. It cannot remain just itself. Thus there is always a sense of loss. It is this sense of loss that makes me use the word ‘condemned’. I am myself being a romantic when I say that first emotions cannot be repeated. But I do not believe that relationships can develop on a romantic level, because… well, because there isn’t really a reason why they should: history, reality, are anything but romantic. And a relationship must feed on reality in order to continue.

Maria Schneider & Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

LAST TANGO IN PARIS

Never (Propose to) Marry a Girl with a Dead Father

Richard Jonathan

Marlon Brando & Maria Schneider, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

An American in Paris. Forty-five. His wife has just committed suicide. He meets a girl in an empty apartment. They fuck. No words, no names.

Maria Schneider & Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

They meet again in the apartment. They fuck again. No names. Words, but nothing personal. Sanctuary. Authenticity. Purity.

Maria Schneider & Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

But the energy of sex that rocks the spine trips the wire of memory. Paul: ‘My father was a drunk. Whore-fucker, bar-fighter… My mother was very poetic, also a drunk, and my memories about when I was a kid are of her being arrested nude.’

Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

And thus the parents enter the room, and Paul begins his regression, trying to become the invulnerable child it’s impossible to be in reality.

Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

On some level Jeanne understands and goes along. She declares her love, she’s found her shining knight: ‘I find this man. He’s you! You are that man!’.

Maria Schneider & Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

But Paul’s not yet done with the trying to undo the knot of love/hate that ties him to his past, and commands Jeanne to put two fingers there where he can obliterate ambivalence. She obeys.

Marlon Brando & Maria Schneider, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

Then he disappears, leaving her devastated.

Maria Schneider, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

Some time later he returns, and lays bare his love: ‘I ran through Africa and Asia and Indonesia. And now I’ve found you. And I love you’. And that’s when she kills him.

Marlon Brando & Maria Schneider, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

Why? Why does she kill him precisely when he tells her that he loves her? Just how complex does feminine desire get? ‘The Colonel had green eyes and shiny boots. I worshipped him. He was so handsome in his uniform’. So said Jeanne of her long-dead father. And, as anyone who’s read Helen Hayward’s study of heroines in the nineteenth-century novel knows, one should ‘never marry a girl with a dead father’. Paul, forty-five in the film to Jeanne’s nineteen, dons the Colonel’s cap and salutes Jeanne just before he declares his love. In killing Paul, Jeanne kills her father. Why? Because Paul-father’s love had removed all limits, making pleasure/pain infinite, and therefore unbearable.

For the psychoanalytic theory supporting this thesis, see, if you read French, Silvia Lippi, ‘La passion du renoncement’, La clinique lacanienne, 2005/2 no 9.

Marlon Brando & Maria Schneider, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

Last Tango in Paris is a film about love as pharmakon: at once cure and poison, the promise of a new beginning and the impossibility of a fresh start.

Marlon Brando & Maria Schneider, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

‘You won’t be free of that feeling of being alone until you look death right in the face’, Paul told Jeanne. He looked death right in the face. From his isolation he reached out in love. And he found that love is colder than death.

‘Love is Colder than Death’: the title of Fassbinder’s first film.

Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

EROS: SEX AND FANTASY

Jessica Benjamin

From ‘Sympathy for the Devil: Notes on Sexuality and Aggression, with Special Reference to Pornography’, in Jessica Benjamin, Like Subjects, Love Objects: Essays on Recognition and Sexual Difference (Yale University Press, 1995), 205-207

What distinguishes the erotic—in interaction or representation—is the existence of an intersubjective space that both allows identification with the other and recognizes the non‑identity between the person, the feeling, and the ‘thing’ (action) representing it. We cannot say that sadomasochistic fantasy is inimical to or outside the erotic, for where do we find sexuality that is free of the fantasy of power and surrender? Would sexuality exist without such fantasy? There is no erotic interaction without the sense of self and other exerting power, affecting each other, and such affecting is immediately elaborated in the unconscious in the more violent terms of infantile sexuality. But what makes sexuality erotic is the survival of the other throughout the exercise of power, which in turn makes the expression of power part of symbolic play.

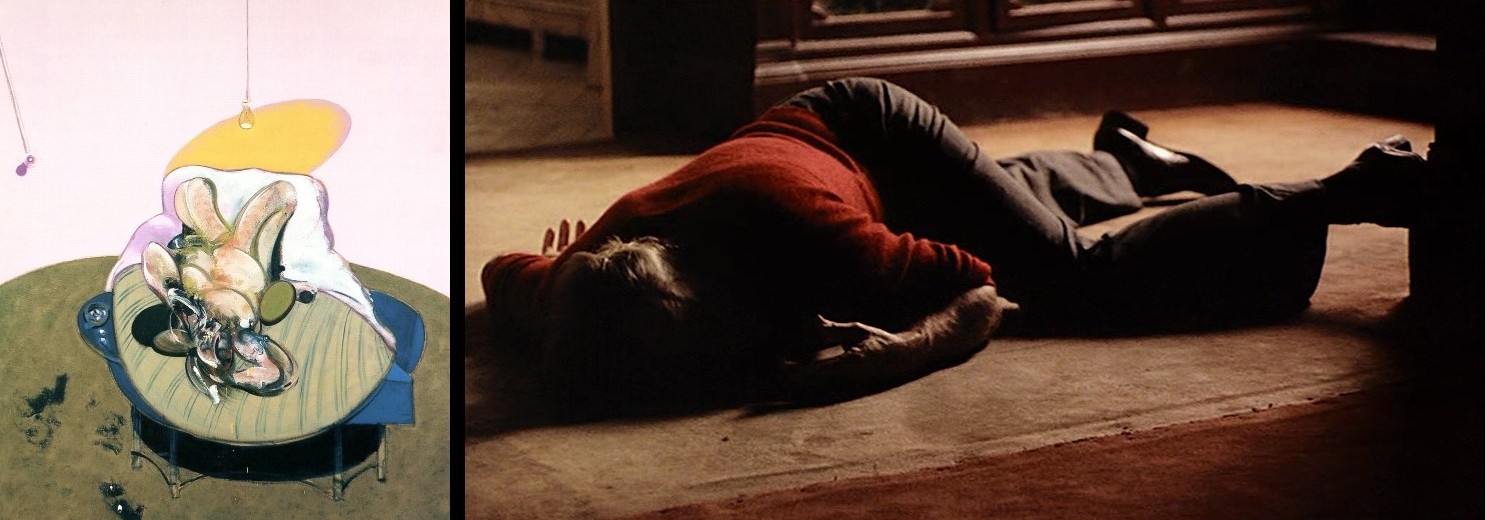

Marlon Brando & Maria Schneider, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

Eros can play with, rather than be extinguished by, the destruction performed by fantasy: when the experience of union (fantasized, perhaps, as devouring or being consumed) can be contained symbolically and does not destroy the self; when sharing and attunement are not destroyed (‘ruined’ or ‘spoiled’) by the other’s outsideness and difference; when separate minds can share similar feelings. Eros unites us and in this sense overcomes the sense of otherness that afflicts the self in relation to the world and its own body. But this transcendence is possible only when one simultaneously recognizes the separateness of some outside body in all its particular sensuality, with all its particular difference.

Marlon Brando & Maria Schneider, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

Perhaps the origins of the erotic can be located before or beyond fantasy in the simple corporeal sensuality and attunement central to the pre-symbolic world of the infant. But the pre-symbolic life necessarily gives way to the symbolic world in which we are able to identify with actions and figures far beyond the concrete by making links between distant and distinct entities, to connect far‑reaching effects. This expansion of the world’s impact on the mind is safe and enriching only when the external is sufficiently differentiated from the internal, when there is a usable outside other: non‑retaliatory but able to be affected, even hurt.

Marlon Brando & Maria Schneider, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

LAST TANGO IN PARIS

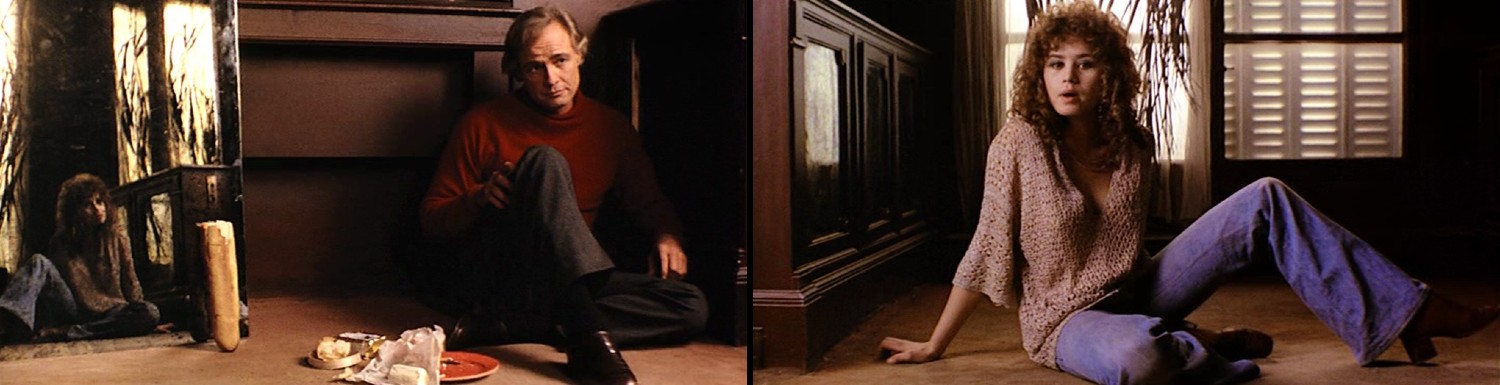

Bernardo Bertolucci on Francis Bacon

From Bernardo Bertolucci, Mon obsession magnifique (Paris: Seuil, 2014) p. 53. This extract translated by Richard Jonathan. The original in Italian was published in Corriere della Serra, 1 May 2007.

When preparing Last Tango in Paris, in the spring of 1972, what I remember most are the frequent visits to the Francis Bacon exhibition at the Grand Palais. I first went with the director of photography, then with the decorator, then the costume designer, and finally, with Marlon Brando. I wanted my closest collaborators to bathe in this carnal despair, this atrocious howl, and to be fascinated and shaken up by it as I was.

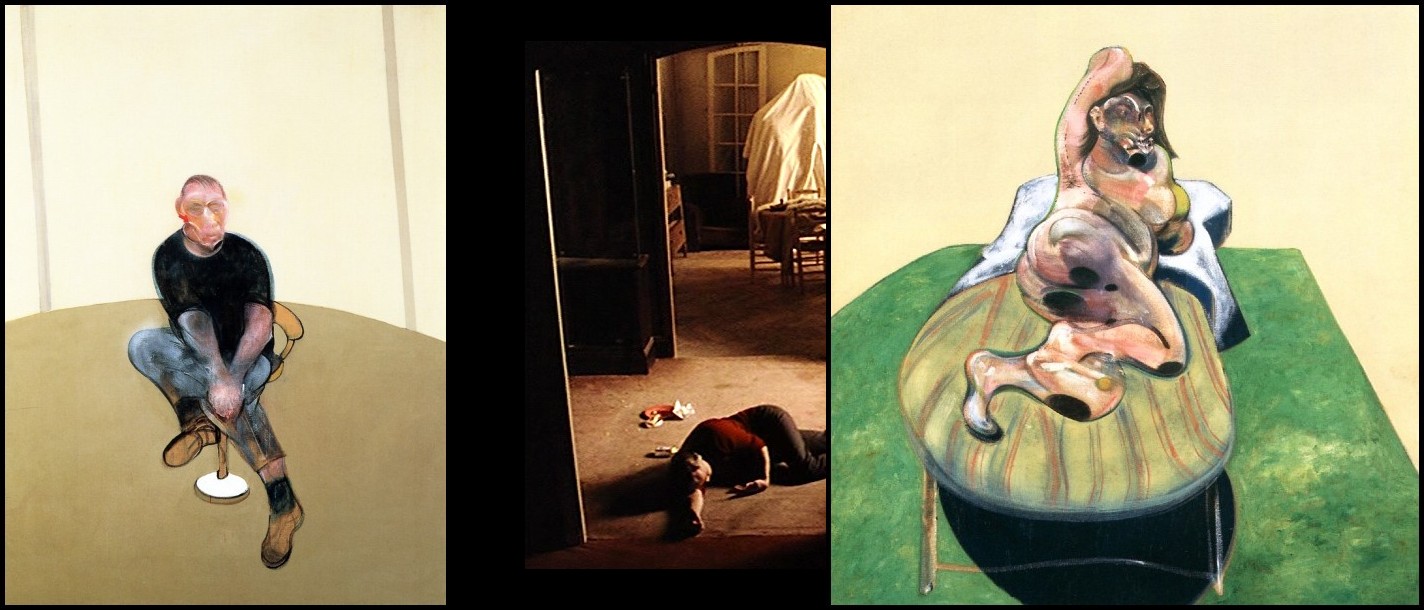

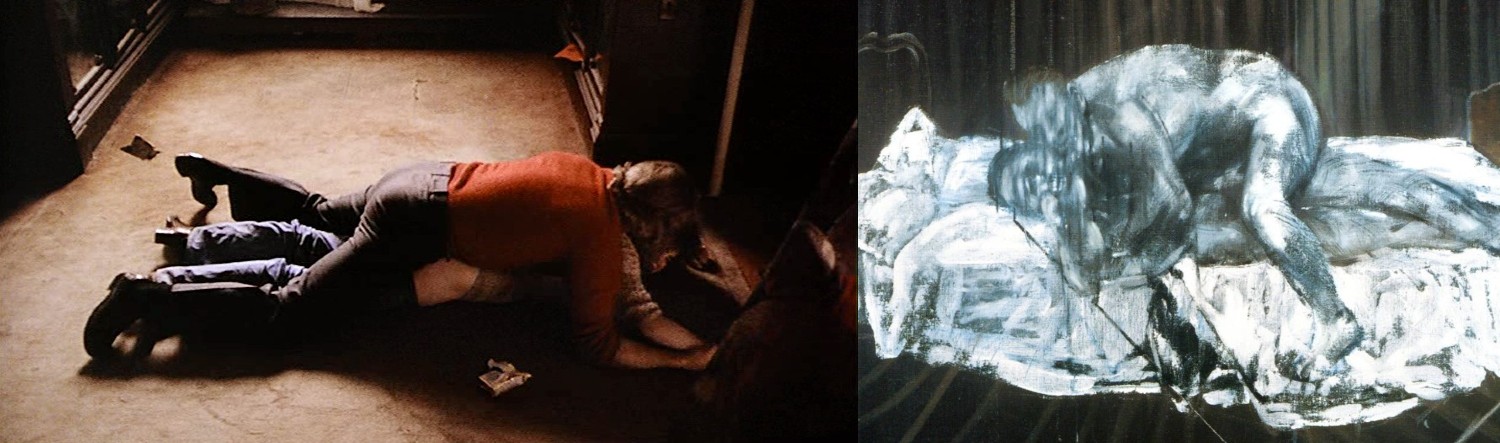

Francis Bacon, Lying Figure, 1969 | Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

I remember at the exhibition there was a certain distance between the paintings, like planets in the void, and we would navigate in this dangerous space, this infinite-Bacon space. When we finished the editing, I realized that the secret heart of the film was formed by those visits to the Grand Palais.

Francis Bacon, Study for Self-Portrait, Triptych (right panel), 1985-86 | Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci | Francis Bacon, Lying Figure, 1969

What the film retains of the influence Bacon had on all of us is, it seems to me, an alarming sense of danger.

Bernardo Bertolucci, Last Tango in Paris, 1972 | Francis Bacon, Two Figures, 1953

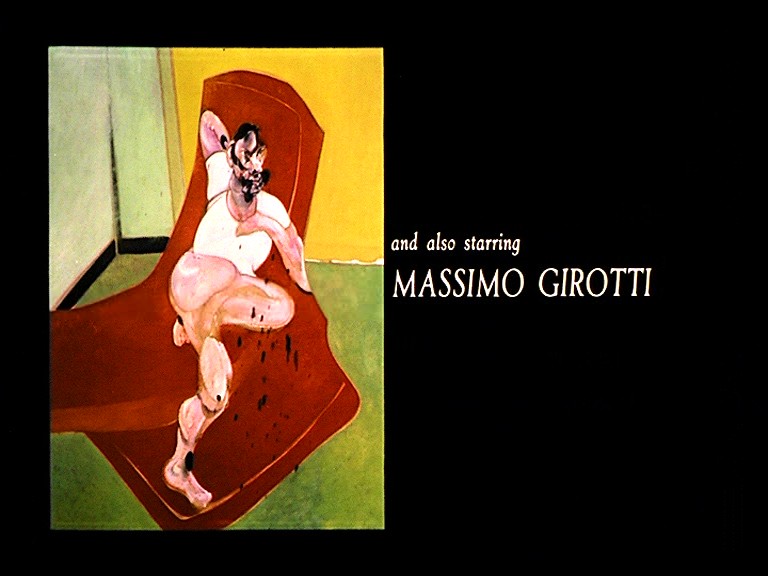

That is why the credits of Last Tango in Paris are placed alongside two Francis Bacon figures, a man…

Francis Bacon, Double Portrait of Lucien Freud and Frank Auerbach (left panel), 1964

… and a woman.

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait (Isabel Rawsthorne), 1964

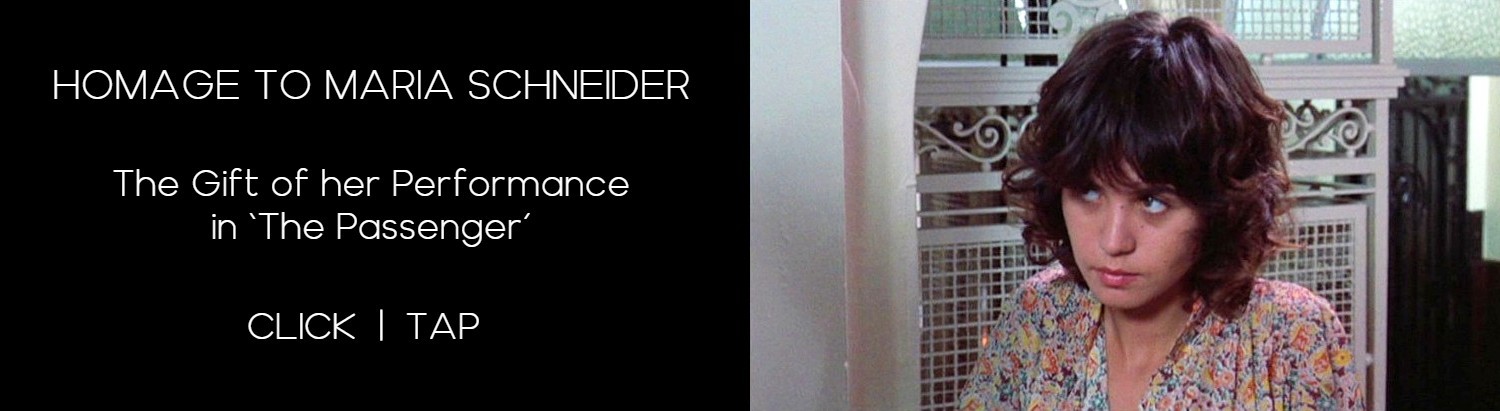

LAST TANGO IN PARIS

Bernardo Bertolucci on Gato Barbieri, Composer & Performer, ‘Last Tango’ Soundtrack

From Bernardo Bertolucci, Mon obsession magnifique (Paris: Seuil, 2014) pp. 228-228. This extract translated by Richard Jonathan. The original in Italian was published in Musica Jazz, No 4, 2007.

LAST TANGO IN PARIS SOUNDTRACK: GATO BARBIERI, COMPOSER; OLIVER NELSON, ARRANGER

You can listen to the tracks in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

Gato Barbieri and I had been friends for a long time. I was at his first Italian concert, in Parma, in 1963. No-one had heard of him then. We were blown away by the sound of his sax, by that ‘dark’ sound. It wasn’t yet the very personal voice that would later make him popular—he was still a very ‘Coltranian’ tenor—but he played with a truly incredible warmth and passion. I asked him to play a piece from the soundtrack of Before the Revolution, a piece composed by Gino Paoli and Ennio Morricone, and that was the beginning of a long friendship. Before and after the sixties, we shared everything, really everything. Gianni Amica, my co-screenwriter on Before the Revolution, got him a residency at the Pesaro jazz festival. The quartet, with Don Cherry, Aldo Romano and Jean-François Jenny-Clark, was fantastic!

Maria Schneider & Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

In 1972, I decided to take Marlon Brando to a Gato concert. Not only did he really dig Gato, but he also literally fell in love with Nana Vasconcelos, the percussionist of the group… With Gato, I insisted on the Argentine soul, the Latin roots. For me, the Gato of Last Tango in Paris was probably a more authentic musician than the Gato who worked with Herb Alpert.

Maria Schneider & Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

The first time he played me the themes for the soundtrack, we started wondering who we could get as arranger. For both of us, Astor Piazzolla was the first name that came to mind. So I called him, all enthusiastic, and he was pretty rude with me, saying he’s a composer, not an arranger, and that the least I could have done would have been to ask him to compose the music for the film. That got us down, Gato and I, even if later we understood that there are not many people on earth—especially among artists—who know how to keep their ego in check.

Maria Schneider & Marlon Brando, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

Then, one fine day, three or four years later, Astor Piazzolla rings at my doorbell in Rome. I invite him up, and he tells me he’s come to apologize, because if he had known what the film would be like, he would have been very happy to do the arrangements of the music. So he apologizes, and says that he adores Last Tango in Paris and regrets his attitude at the time. Then he gives me a 45 rpm and says: ‘Here’s a little present for you. It’s called, ‘The Tango Before Last’… Of course, it was Oliver Nelson who we finally chose to arrange the music. He was a professional arranger, and had already done film music.

Marlon Brando & Maria Schneider, Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci

LAST TANGO IN PARIS: A CAROUSEL OF STILLS, IN SEQUENCE