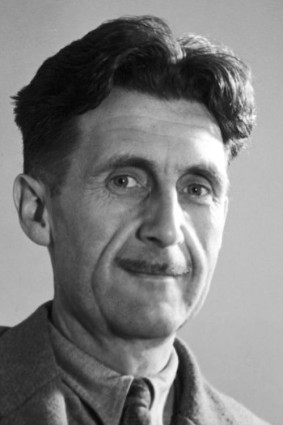

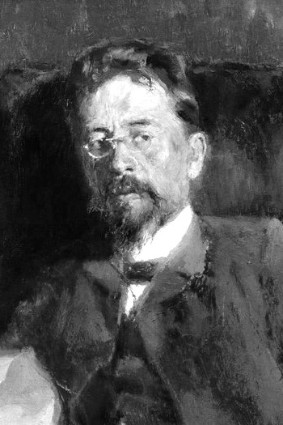

FRANZ KAFKA

John Zilcosky on Kafka’s ‘Letters to Milena’

THE TRAFFIC OF WRITING: TECHNOLOGIES OF INTERCOURSE IN THE ‘LETTERS TO MILENA’

Posted by kind permission of John Zilcosky, Professor of German & Comparative Literature, University of Toronto

Abridged from John Zilcosky, Kafka’s Travels: Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) pp. 153-73

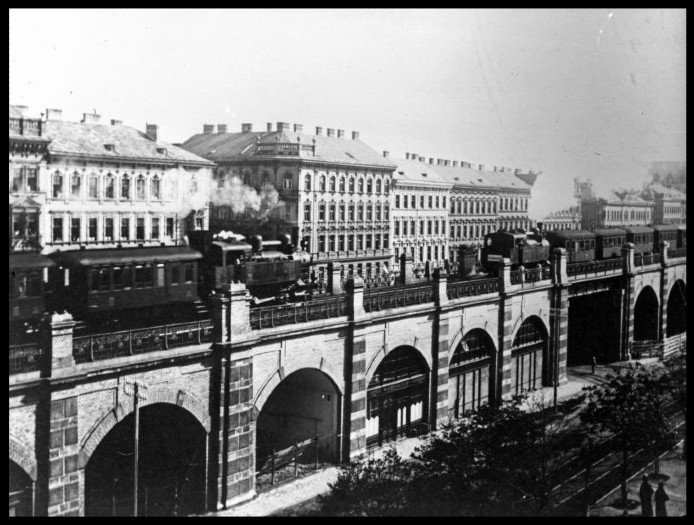

I. ‘NATURAL’ INTERCOURSE: SEX AND TRAINS

By the time Franz Kafka began writing letters to Milena, the new bureaucracies of rail ministry and postal service were firmly in place. Before the mid-nineteenth century, neither Germany nor Austria had a rail ministry, and their postal services were housed together within the Verkehrsministerium (transport ministry). In other words, before the 1850s, traveling bodies and traveling letters were administratively united. The eventual bureaucratic separation of body from information brought with it, by the turn of the century, another, physical separation: bodies and messages no longer necessarily traveled in the same vehicles. With the invention of pneumatic mail, the telegraph, the telephone, and the wireless, information often no longer used traditional vehicles at all. People stopped speaking of ‘traveling by the night mail,’ and began to imagine that trains and, later, automobiles were the exclusive province of human bodies.

Steam train, 1927

Such technological and bureaucratic changes led to new ways of thinking about the body’s relation—or non-relation—to transported information. According to Kafka, the world was divided technologically into two groups: the technologies encouraging human presence (train, automobile, aeroplane, etc.) and the technologies encouraging absence (postal system, telegraph, wireless, etc.). The technologies of presence, Kafka suggests, promote ‘natürlichen’—that is, physical— ‘Verkehr’ (traffic, intercourse [social and sexual], circulation) between humans, while the technologies of absence sponsor a disembodied ‘Verkehr mit Gespenstern’ (intercourse with ghosts). On the one hand Kafka desires the ‘natural’ intercourse sponsored by trains; on the other hand, he passionately wants to continue writing letters. For most of the correspondence, Kafka chooses the latter. He is ‘made of literature,’ he once wrote to Felice and thus would rather read his lovers’ letters than touch their bodies. This oft-cited opposition between presence and absence structured Kafka’s epistolary relations with Felice and, at the beginning, with Milena.

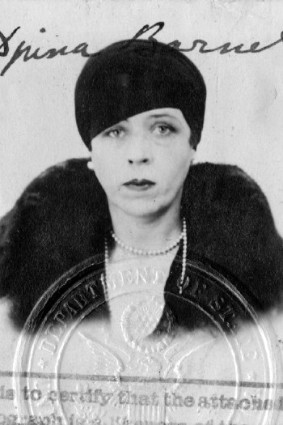

Milena Jesenská, 1917

Kafka wrote ‘Frau Milena’ at least 126 letters between April and December 1920, and throughout these letters, he postpones an ever-promised journey to visit her. This journey, which would achieve physical presence and thus temporarily halt the correspondence, is, significantly, a train journey. As contemporary psychoanalysts speculated, trains had already pervaded the collective fin de siècle unconscious as a symbol of sexuality. Freud claims in 1905 in Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality that this symbolism begins shortly before male puberty, when boys develop ‘an extraordinarily intense interest in things connected with railways’; they subsequently use the rail system as ‘the nucleus of a symbolism that is peculiarly sexual.’ Similarly, Karl Abraham reports in 1922 that the sexual neuroses of many of his patients are ‘related to the danger of finding themselves in a kind of unstoppable motion that they can no longer control.’ These patients feared locomotion in any vehicle they could not bring to a halt themselves at any time—most notably, Abraham remarks, in railway trains.

Train leaving station, 1927

For Freud and Abraham, the railway’s gender was symbolized by the station and the locomotive, respectively. In his famous Bruchstück einer Hysterie-Analyse from 1905 (the ‘Dora’ case), Freud interpreted the station (Bahnhof) as a dream-symbol for the ‘female genitals’; that is, as a site of Verkehr. Playing on a possible unconscious connection between the feminized Bahnhof and Verkehr, Freud coyly remarks: ‘A ‘Bahnhof’ is used for purposes of ‘Verkehr’. Following Freud’s remarks on the feminized station, Abraham argues that the locomotive, correspondingly, is a phallic dream-symbol—thrusting forward (‘Vordringen’) with ‘inexorable violence.’ Freud even goes so far as to suggest that the railway’s sexual symbolism results directly from the mechanics of turn-of-the-century train travel. The turbulence produced by this early, rather crude system of rails, wheels, and springs, he writes in his Three Essays, causes involuntary ‘sexual excitation’ in the traveler’s body.

Train in station, 1927

Although Kafka never explicitly connected train travel to sexuality, this widespread cultural fantasy—at once nurtured and diagnosed by psychoanalysis—affected his relations with Milena and connects his early fiction to the rubric of Verkehr. Kafka’s interest in the symbolic alliance of modern traffic and sexuality appears in ‘The Passenger’, ‘Description of a Struggle’, The Man Who Disappeared, The Metamorphosis, and, most obviously, ‘The Judgment,’ which ends with the word ‘Verkehr’ and the image of motor-bus passing over the drowning protagonist. Kafka had ‘thoughts about Freud’ throughout the story and even, according to Brod, imagined a ‘violent ejaculation’ while writing the last line.

Motor-bus, 1928

Kafka’s fascination with traffic and intercourse in the Letters to Milena predates his punning notion that the vehicles of modern Verkehr promote human Verkehr. In an early letter in which he, for the second time, rejects Milena’s invitation to visit her, Kafka nominally connects the rail system to his two prospective sexual partners: Milena and his fiancée at the time, Julie Wohryzek. Kafka tells Milena that he might change his mind and visit her instead of Julie, as originally planned; in the course of describing his indecision, he leaves out the names ‘Milena’ and ‘Julie’ and replaces them with the names of their respective railway stations. Julie, here, is recognizable only through the word ‘Karlsbad’ and the ‘short route via Munich,’ while Milena appears only through the ‘secret code’ denoting ‘Vienna’ and ‘Linz’:

A telegram arrived ‘Meet at Karlsbad eighth request written communication.’ Occasionally I look at the telegram and can scarcely read it—as if it contained a secret code, one which effaces the message and reads: ‘Travel via Vienna!’ I won’t do it, even just on the face of it it’s senseless not to take the short route via Munich, but one twice as long through Linz and then even further via Vienna.

Railway schedules—the ‘short route via Munich’ and the one ‘twice as long through Linz’—stand in for the names of the beloved. The rail route—’Travel via Vienna!’—becomes Kafka’s ejaculatory expression of desire.

Julie Wohryzek

In this and other early letters, the rail system develops a sexual undercurrent not unlike the one already embedded in the word Eisenbahnverkehr (‘rail traffic’). Five days following this letter, Kafka warns Milena that a rumored rail strike would cut him off from all ‘Eisenbahnverkehr,’ and thus also from all physical intercourse with her. Although the strike does not occur, Kafka voluntarily abstains from train traffic: he repeatedly postpones his departure over the course of nearly a month, thereby choosing letter writing over physical presence. He returns to writing, and proceeds to discuss with Milena possible train routes and rendezvous. By including rail schedules in his letters, Kafka contains what appears to be a dangerous, sexualized Verkehrsnetz (transport network) within a ghostly network of codes—and thereby eroticizes the delay of gratification through modernity’s chief figure of deferral, writing. If the rail system threatens to transport his body, Kafka will retaliate: he will transpose this network into an order of signs, an endless traffic of letters. We might imagine Kafka sitting at his desk, vigorously fending off Eisenbahnverkehr by copying timetables into his missives. Indeed, from another such desk in Prague, months later, Kafka tells Milena that he is studying the timetable she sent him ‘like a map’. This ‘study’-able timetable, like Kafka’s letters to Milena themselves, represents how trains can become texts.Travel, Kafka hopes, might fully be transposed into signs.

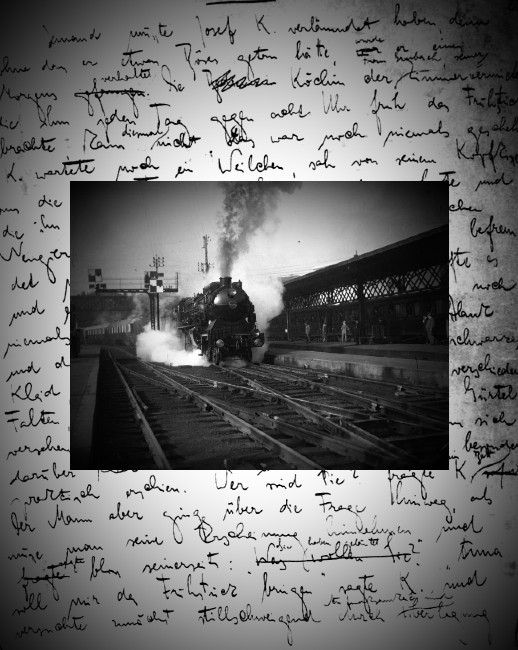

Steam train | First page, original manuscript, The Trial

II. Dream: ‘Eisenbahnverkehr’ (Rail Transport) versus Letter Writing

On 14 June 1920, following his month-long deferral of departure, Kafka relates to Milena two dreams (one a waking dream, the other real), in which he travels to Vienna. These dreams stage Kafka’s conflicting, technologized desires for both absence and presence. Here, as in his discussion of timetables, Kafka pits modern, sexualized Eisenbahnverkehr against the postal service. Kafka’s real dream thus begins with a journey to Vienna. He writes that his body overtook his ‘own letters, which were still on their way to you’. In comparing the relative travel time of body and letter, Kafka here invokes the newly established technocratic difference between human transport and information transmission. Anachronistically, he claims that transport technologies still outpace information technologies: bodies will arrive before letters. For this reason, Kafka, the enthusiastic letter writer, claims to experience ‘particular pain’.

Steam train, 1927

For this first section of the dream, as well as for the entire waking dream, sexualized Eisenbahnverkehr holds sway over letter writing. Kafka’s dream-body repeatedly appears at some pleasurable site of transit: a railway hotel, railway station, a thoroughfare. In his waking dream, similarly, Kafka finds himself in a hotel near the stations, situated among Milena’s house and the arriving and departing trains: ‘Opposite your house is my hotel, to the left is the Westbahnhof where I arrive, to the left of that the Franz Josefs Bahnhof from which I depart’. The great city of Vienna is reduced to one railway hotel, Milena’s house, and, in the terms of contemporary psychoanalysis, two sexually charged train stations. The aroused dream-subject, traveling to meet his beloved, arrives (comes) into the center of this Eisenbahnverkehr. In the real dream, the city condenses more distinctively into a sexualized metropolis: ‘wet, dark, an inconceivable amount of traffic’.

Germaine Krull, Haus Vaterland, Berlin, 1924

In the middle of this dream, Kafka finds himself at another libidinal site of transit: a twilit thoroughfare. This thoroughfare, like the illogically speedy express train before it, allows the dreamer to traffic physically with Milena: ‘I had one foot in the roadway,’ Kafka writes, ‘I was holding your hand’. But here, unlike in the previous scene, new, rival communication technologies appear to challenge ‘natural Verkehr.’ At the precise moment at which Kafka and Milena hold hands, they are interrupted, ironically, by their own ‘conversation,’ which takes on a life of its own: ‘it’ simply ‘began’ and then continued, without Kafka or Milena being able to control it.

Germaine Krull, Romanisches Café, Berlin, 1929

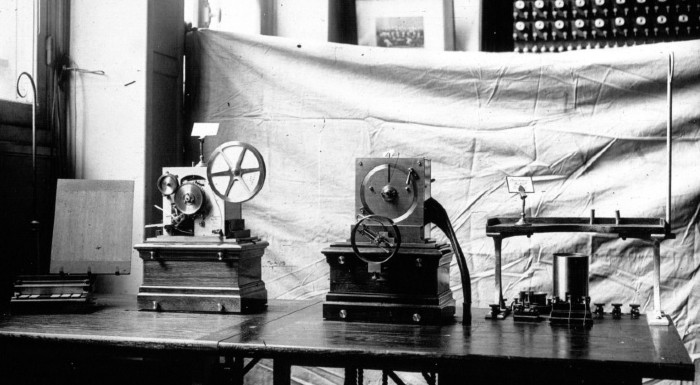

This autonomous conversation recalls the lovers’ own epistolary conversation, which, according to Kafka, developed independently of and often in opposition to its own authors. Indeed, the dream conversation’s insanely fast tempo, punctuated syntax, and rhythmic clacking (‘klapp klapp’) suggest a telegram—a machine Kafka often used to communicate with Milena. This medium, inestimably faster than the technologies of human presence, intrudes on the lovers’ physical intercourse. The content of the telegrammatic klapp klapp, Kafka claims, is agony, the same word he later uses to describe the content of all of his correspondence with Milena. This agonizing clatter could be dream-shorthand for modern media traffic—suggesting that this form of traffic, the lightning-fast telegram, is superior to travel technologies and, moreover, anathema to physical intercourse. The lovers are frustrated by the virtually uninterrupted klapp klapp of their own dialogue, which eventually transforms their relationship from hand-holding into uncomfortable ‘negotiations’. What began as a seemingly harmless telegrammatic cacophony ends in melancholic separation. The dream thus realizes a nightmare that has secretly haunted the entire correspondence: modern media technologies sabotage the lovers’ chances for satisfying physical intercourse (and eventually reveal how such physicality is always already mediated).

Telegraph machines, 1923

But Kafka’s dream, we must remember, began by documenting his desire for precisely such a sabotage: he experiences pain when his train-transported body overtakes his letters. Kafka’s dream is thus as ambivalent as is its dreamer. It displays Kafka’s desire to experience mediated and unmediated physical intercourse at once. Without the former, he is in pain; without the latter, he experiences agony. When the dream is over, however, we again see which side Kafka takes when forced to make a choice. He does not embark on the already long-postponed journey but rather sits down to write Milena another letter, a letter about his ‘horrid’ dream. Kafka thus enlists agonizing media technologies to tell the story of agonizing media technologies. His only pleasures come from return mail. Two hours after the dream, he proudly reports, he received ‘consolation’: letters and flowers from Milena.

Telegraphic transmission apparatus between train carriages, 1914

III. A Victory for Natural Intercourse, Then More Letter Pleasure

Kafka’s journey to Vienna on 29 June 1920 marks, as the letter-addict both desired and feared, the first gap in his correspondence. The ‘natural’ intercourse of trains temporarily shuts down the klapp klapp of communication technologies, and Kafka enjoys, for four days, physical—and perhaps sexual—intercourse with Milena. In the letters following his return, Kafka fondly remembers Milena in relation to the sexualized rail system, specifically, as part of the feminized Bahnhof. Kafka twice claims that he can only remember Milena’s face as it was at the station. He remembers her sad station-face, and later, when describing the problems he has with customs officials while crossing the border back to Czechoslovakia (Kafka’s Austrian visa has expired), he claims that ‘Milena’ spiritually assisted him with the station officials. She becomes his travel angel; as he puts it further, she is the ‘angel of Jews’.

Steam-powered trams, Vienna, 1910

With Milena in the role of travel angel, Kafka takes on the job of letter magician. In his first letter upon returning to Prague, he describes missing Milena’s physical presence: ‘suddenly you were no longer there; or, better, you were there, although this kind of being-there was very different from what we knew during the 4 days’ (Kafka’s emphasis). Milena’s new kind of being there is a familiar one: she is ‘there’ but only as writing on a page, as an epistolary projection; Kafka claims that he must once again become ‘accustomed’ to this kind of presence. He thus rehabituates himself to letter writing, in the form of the mournful magician. He writes Milena three letters on the day of his return and, in one, imagines conjuring her missing body simply by mailing a letter: ‘I’m sending you the letter, as if by doing so I could transport you next to me, especially close’.

Germaine Krull, Rails, 1927

The partnership between travel angel and letter magician, cooperative at the start, grows increasingly contentious. After a couple of weeks of writing optimistically about another meeting, Kafka begins to regard with suspicion his travel angel’s facility in transporting his body. He negatively revises his memory of their meeting and resists her entreaties once again: ‘I won’t come,’ he writes resolutely and, later, ‘I cannot come’. This renewed refusal coincides exactly with his reintensified efforts to conjure Milena’s body via letters.

Germaine Krull, Rails II, 1927

On 30 July 1920, Kafka announces his refusal to visit for the first time; on this same day, he also initially speaks at length about the material qualities of what he later calls Milena’s ‘beautiful’ telegram. Like the vampiric ghosts whom Kafka later accuses of having greedily drunk up his and Milena’s ‘written kisses,’ Kafka claims to imbibe—or suck up—Milena’s telegram while reading it. Kafka later fingers this telegram ‘constantly’ and gains a ‘special’ feeling from having it in his pocket. This beautiful telegram—like Milena’s beautiful handwriting before it—fetishistically replaces the absent lover’s body. Months earlier, when Milena complained to Kafka that his face was becoming nothing more to her than ‘stationery that has been written on’, Kafka defends the pleasures of epistolary absence: ‘I am so much better off than you!’ he writes, ‘the true Milena is here, and believe me, being with her is wonderful’. Fetishistic pleasure thus ameliorates the pain caused by letterary distance. Kafka refuses to visit Milena but is magically able to transfer her essence to him. Through epistolary necromancy, then, the lover is present and absent at once.

Germaine Krull, Metal (plate 22), 1928

Kafka thus separates himself, as letter-writing conjuror, from Milena, the sexualized ‘angel’ of the rails. In these same post-Vienna weeks, Kafka not surprisingly hones his mastery of communication technologies—switching adroitly from letters, to pneumatic mail, to telegrams. He blatantly reveals, in a late July letter, his preference for postal over physical intercourse. In response to Ernst Pollak’s (Milena’s husband) plans to move the couple as far away as Paris or Chicago, Kafka only cares about whether or not he will still be able to write to her once she’s there—wondering aloud if she will go to a ‘place with good mail service?’.

Germaine Krull, Roller Coaster and Ship, n.d.

IV. Another Promise of Natural ‘Verkehr’;

A Postal Utopia; and the End of the Correspondence

By his own accounts desperate, Kafka resorts to a promise of ‘natural intercourse’ in order to guarantee that the material essential to life—letters, stamps, telegrams—will continue to arrive. He promises to meet Milena either in Vienna or the Austrian/Czech border town of Gmünd. The theme of these early-August letters correspondingly turns abruptly from stamps to trains. From August 1-3, Kafka mentions train schedules five times—sometimes in exacting detail, as in what he here terms plan number ‘II’: ‘I likewise leave here at 4:12, but am already (already! already!) in Gmünd by 7:28 P.M. Even if I leave with the morning express on Sunday, it’s not until 10:46’. He doesn’t really want to be near her, but wants her on the line. So he talks around her. Later in the same letter, Kafka mentions his earlier stamp exchange with Milena again, but this old theme is beginning to feel like a fairy tale that has lost its powers to enchant. Kafka knows that he must replace his stamp stories with some new talk of trains: ‘Yes, you’re doing excellently with the stamps. I’ll even send you some Legionnaire stamps, imagine. I don’t feel like telling any fairy tales today; my head is like a railroad station, with trains departing, arriving, customs control’.

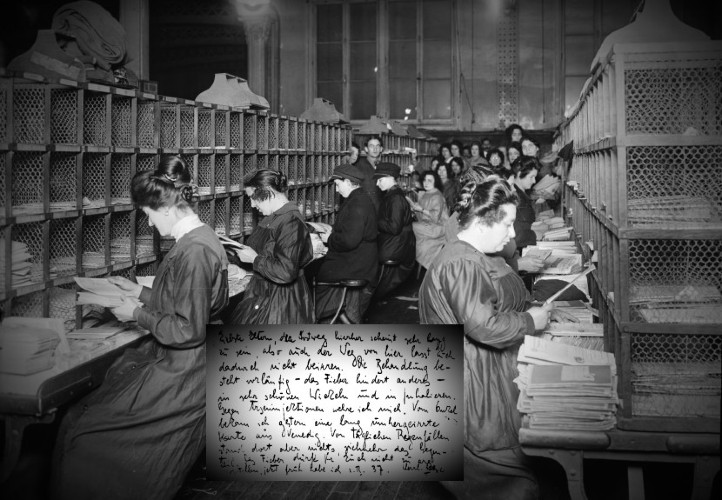

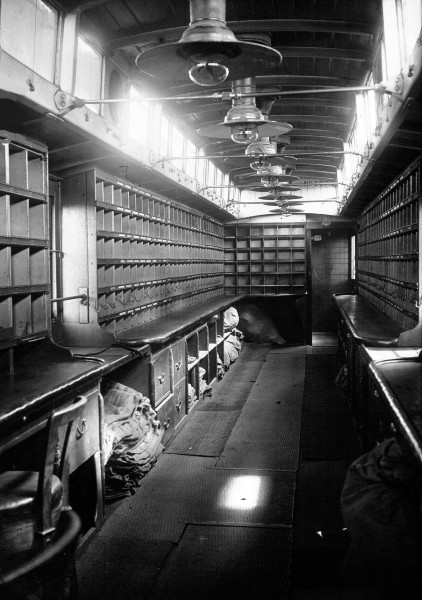

Mail train, 1928

Kafka allows this flood of train traffic to overfill his suddenly technologized ‘head’ and, what is more, to dilute his desire to tell stories (about stamps). But this cannot weaken his unswerving appetite for composing and receiving letters. In fact, the re-introduction of the theme of ‘natural intercourse’ leads again dialectically to more letter traffic. In the four days following this offer to travel, Kafka writes seven letters and at least three telegrams, and Milena responds. The opposing discourses of trains and telegrams encourage one another again—and again to the final benefit of letter traffic. Kafka reveals his understanding of this dynamic on August 3. Amid more discussions of trains and schedules, he asks Milena to make even more trips to the post office: ‘answer me by telegram whether you, too, can come. So keep going to the post office in the evening as well’.

Sorting Room, Post Office, 1923 | Inset: Postcard sent by Kafka to his parents, 1924

Kafka meets Milena in Gmünd—like the Mund (mouth), a site of natural intercourse—on August 14-15. In the months that follow, Kafka mentions farewell (‘Abschied’) for the first time and, finally, that winter, severs the correspondence and begs Milena to do the same. What brings Kafka to end this correspondence, even though he once claimed that receiving letters endowed him with ‘everything’? Critics, including the editors of the latest German edition of Letters to Milena, have tended to explain this termination according to two contradictory relationship economies: Kafka realized that he could not give Milena the level of sexual intimacy she needed; or, conversely, Kafka wanted the kind of intimate relationship a married woman could never give him. What these opposed readings overlook is the relation of content to form; that is, the connection between Kafka’s desire to stop writing letters and the structural exigencies of epistolary exchange. The writer of love-letters desires to be absent and present at once, and modern technologies encourage but do not satisfy these contradictory yearnings. Rather, trains and telegrams set such longings more acutely against one another.

Mail train (interior), 1921

Kafka had a recurring fantasy that would allow him to mend this techno-psychological rift: he would send his own body to his lover. This vision is first articulated by one of Kafka’s earliest protagonists, who dreams, in Wedding Preparations in the Country, of sending his own ‘clothed body’ to his fiancée while himself staying at home. This fantasy of what Wolf Kittler calls a ‘postal utopia’—of becoming mail, of becoming a stamp—grows stronger and more literal in the weeks leading up to Kafka’s journey to Gmünd, when he first imagines packaging his own body in the mail. Kafka had been sending needed books and other items to Milena (now living in inflationary, post-war Austria), and he claims that he will literally ‘crawl into every item your list contains just in order to travel inside it to Vienna, and please give me as many opportunities to travel as possible’. The image here is of Kafka magically shrinking and multiplying himself, then crawling into books and other items, and, finally, mailing these many selves. This vision combines technological fantasy with bureaucratic subversion. It allows Kafka (multiplied) to traffic physically with Milena while, at the same time, maintaining his single, epistolary self. A normal-sized, unshrunk master Kafka, one must assume, serves as writer, packager, and sender.

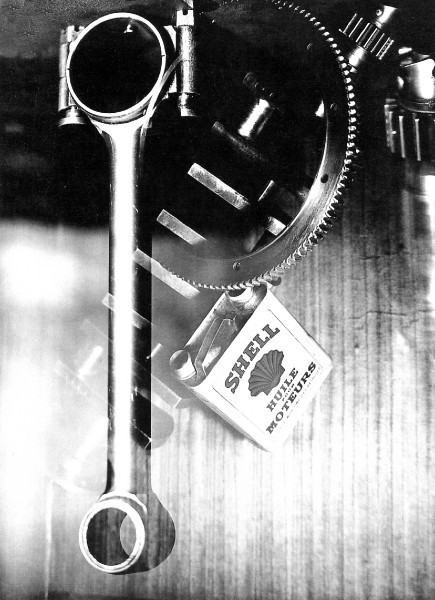

Germaine Krull, Metal (plate 47), 1928

Kafka’s techno-postal fantasy is, of course, never realized. He visits Milena in Gmünd, traveling by train, not parcel post. By Kafka’s account, the meeting is unsatisfactory. He returns to Prague and is once again deeply split between body and letters. Unlike the cheerful fantasy of crawling into a postal package, the reality of traveling on a train now causes Kafka great fear. He writes to Milena that he is ‘afraid of traveling,’ afraid of coughing uninterruptedly as he had for over an hour the night before. As the now-tubercular Kafka continues, he ‘wouldn’t dream of taking a sleeping car’. Traveling, here, again exposes Kafka’s body to the world. Instead of revealing the body’s sexuality, travel now emphasizes its illness. Now the infected body (not the sexualized one) is on display, but the sudden and unwilling exposure of this body to others—and vice-versa—remains Kafka’s central distress. Eisenbahnverkehr (rail traffic) he fears, will lead to more non-linguistic physical intercourse, even to death, and again bring about—irrevocably, this time—the end of Schriftverkehr (the traffic of writing).

Germaine Krull, Shell Oil, n.d.

In the final months of the correspondence, Kafka grows increasingly aware of this split between traveling (physical) and writing (ghostly) selves, and of this fissure’s deleterious effects on him. He is once again in the throes of indecision in his last 1920 letter to Milena—unsure again whether or not to visit her. He sums up his recurring epistolary-existential dilemma—to travel or not to travel—in the form of a letter about a letter and a journey. He writes: ‘Two people were struggling within me; one who wants to travel and one who is afraid of traveling—both just parts of me, both probably scoundrels’. Kafka’s ‘worst times’ are thus brought on, again, by the impossibility of combining traveling and writing selves. The writer-in-love cannot replicate and mail himself to his lover but must, rather, subsist as either the epistolary lover afraid to travel or the traveling lover unable to write. Incapable of being both at once, Kafka chooses to become neither: he stops writing to Milena for over fifteen months.

Germaine Krull, Eiffel Tower, 1928

V. The Final Letters

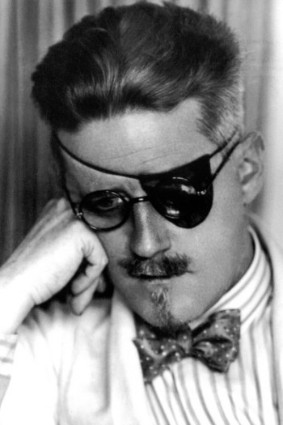

When Kafka finally writes again (late March 1922), he is distant and formal, referring to Milena as ‘Sie’. He is no longer struggling from within the techno-psychological dialectic of letterary love; rather, he theorizes about it from a temporal and emotional distance. He now sees the technologies that supported his ‘agonizing’ long-distance love affair with Milena as pernicious, even inhuman. As was the case in his breakthrough story, ‘The Judgment,’ writing and physical love are here explicitly opposed. The postal system, the telegraph, and the wireless, Kafka claims, alienate bodies from themselves and from each other—thereby permitting lovers only ‘ghostly’ intercourse:

Writing letters is actually an intercourse with ghosts. How did people ever get the idea they could communicate with one another by letter! One can think about someone far away and one can hold on to someone nearby; everything else is beyond human power. Written kisses don’t arrive at their destination; the ghosts drink them up along the way. It is this ample nourishment which enables them to multiply so enormously. Humanity senses this and struggles against it.

Germaine Krull, Eiffel Tower, 1928

‘Humanity’s’ struggle takes the form of innovations in the technologies of transport:

In order to eliminate as much as possible the ghostly element between people and to attain a natural intercourse, a tranquility of souls, humankind has invented trains, cars, aeroplanes—but nothing helps anymore: These are evidently inventions devised at the moment of crashing. The opposing side is so much calmer and stronger; after the postal system, the ghosts invented the telegraph, the telephone, the radiotelegraph.

Germaine Krull, Metal (plate 9), c.1925-28

Toward the end of this late letter, Kafka expresses, one final time, his desire to sidestep the dialectic of trains and telegrams by mailing himself. He closes these negative remarks on travel- and communication technologies with the tempting notion that human presence could be magically posted. Kafka suggests that one of his or Milena’s letters could arrive miraculously in the form of a pleasing, longed-for ‘handclasp’. Letter transforms here into hand, message into body. This seductive image allows Kafka again to achieve the super-human, the virtual. He stays home and writes, while his body, as in Wedding Preparations, travels to his lover. This fantasy is so powerful, so attractive, Kafka continues, that it is the ‘most dangerous of all,’ and thus must be guarded against ‘more carefully than the others’.

Franz Kafka, a drawing from his diary

Kafka indeed chooses to guard himself, by abstaining from epistolary love. He writes to ‘Frau Milena’ only seven more times until his death in 1924 (four letters, three postcards) and maintains the formal distance of ‘Sie’ all but once. In his final postcard (from December 25, 1923), Kafka acknowledges that his writing seems to have lost its previously thrilling and dangerous capacity for conveying bodies. This ability has deteriorated, Kafka claims, as has his own body. Writing can no longer transport a self. It can barely even convey the most insignificant of messages into the world of threatening and enticing human Verkehr, the world of ‘Frau Milena’: ‘if I write down ‘cordial regards,’ then are these greetings really strong enough to enter the wild, noisy, gray, urban Lerchenfelderstrasse [Milena’s home street], where it would be impossible for me and mine to even breathe?’. This ‘love’ letter, not surprisingly, is Franz Kafka’s last.

Franz Kafka, a drawing from his diary

VI. Coda: Epistolarity and a Fictional Marriage

When Kafka wrote this final postcard to Milena, he was living in Steglitz in Berlin with Dora Diamant, a young Jewish woman from Galicia. Kafka had thus finally completed the longed-for journey from Prague to Berlin as well as toward the satisfactory ‘home’ with a woman. He and Dora had planned another admittedly impossible journey, to Palestine, where they imagined opening a restaurant—with her the cook and him the waiter. But Kafka and Dora (like Kafka and Felice a decade earlier) never made it to the Promised Land. Kafka’s condition worsened, bringing the couple first to Prague, then to one sanatorium, and then to another, final one in Austria. Three of Kafka’s lifelong journeys, therefore, moved toward a close in 1923: out of Prague, toward a conjugal relationship with a woman, and toward death.

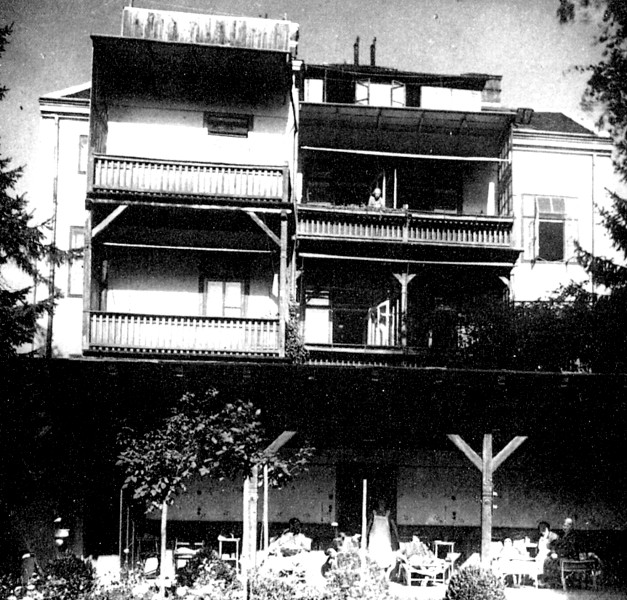

Sanitarium near Vienna where Kafka spent the last six weeks of his life

Kafka’s and Dora’s effective marriage was accompanied by a fictional one that, as did Kafka’s endlessly delayed bondings with Felice and Milena, takes place in letters. It performs the precise tensions between travel and writing, between sexual Verkehr and epistolary distance—albeit this time with a happy ending. According to Dora, Kafka met a little girl crying one morning in a park because she had lost her doll. Kafka comforted her, ‘Your doll is just traveling, I know, she sent me a letter.’ The child was suspicious: ‘Do you have it with you?’ ‘No, I forgot it at home, but I’ll bring it to you tomorrow.’ Kafka returned home and composed a letter, with the same seriousness he devoted to his writings—be they postcards, letters, or stories. He went back the following day and read the letter to the girl: the doll explained that she had grown tired of living in the same family, and needed a change of air and locale. Although she still thought very fondly of the little girl, she needed to be away from her for a time.

Germaine Krull, Girl with Dolls, n.d.

She promised to write every day, reporting about her adventures in foreign lands. So Kafka wrote each day, as he had earlier to Milena. And, as he had twelve years before in Amerika, he described countries and people that he knew only in fantasy. The doll told of her far-off adventures, of her new school, of the interesting people she met. The child soon forgot about her missing plaything, losing herself in the humorous detail of Kafka’s fiction. Continually reassuring the child that she loved her, the doll nonetheless hinted at complications in her life, at her various duties and interests. This game went on for at least three weeks. Kafka suffered terrible anxieties when he thought about ending it. The ending, he knew, must restore order to the girl’s life—order that had disappeared the moment she lost her doll. He ultimately decided that the doll would get married. Describing the young man, the engagement celebration, the wedding preparations, and finally all the particulars of the newlyweds’ home, the doll told the little girl in the end: ‘As you see yourself, in the future we will have to do without seeing each other again.’

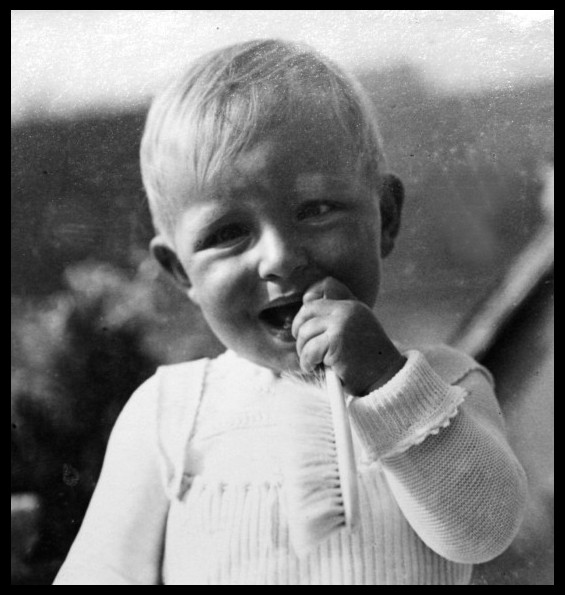

Germaine Krull, Child with Hairbrush, n.d.

In this epistolary fiction, which survived only in Dora’s memory, Kafka achieved what he never could with Milena. Although no trains are mentioned, Kafka reiterates the tension between presence and absence—between conjugal intimacy and letter writing—that produced much of his struggle with Milena. The forces of Verkehr—of travel and social intercourse—encourage the doll to become sexual and, in the end, marry. And, here, unlike in Kafka’s life, the world of letters does not stand in opposition: rather, the letters are what allow the doll to successfully and considerately grow up and away from her family. Only in Kafka’s fiction, then, can letters fulfill their promise of intimacy. The doll can marry because the letters acceptably generate distance from the girl, who represents, here, the retarding force of the family or, more generally, the ever-present debilitating ‘third’ in Kafkan love affairs. It is as if Georg Bendemann had, before the beginning of Kafka’s 1912 breakthrough story, informed his ‘friend’ of his coming marriage, stopped writing, and left home with his fiancée. It is as if Kafka, in the dream of unfulfilled travel, had left his family already in 1912 and traveled to Palestine with Felice—creating a new exotic Heimat with his lover, beyond the imperial reach of the father, where he could finally stop both traveling and writing.

A Wedding, 1920

Perhaps Kafka reached this Promised Land beyond letter writing with Dora, even though the two of them never made it to Palestine, as they had hoped. Like the doll in his story, Kafka finally used letter writing to break away from Milena (and from the little girl in the story) and eventually stopped writing love letters in order to move to Berlin (for Kafka, an ersatz Palestine, where he could live with Dora). What is more, Kafka wrote very few letters to Dora (none have survived), and Dora—unlike Max Brod—agreed to Kafka’s earnest request to burn some of the writings that he imagined were torturing him. Dora’s story is the story of the defeat of epistolarity, of the use of letter writing as a means to end letter writing: letters only allow for acceptable separation and are then discarded in favor of conjugal intimacy. But ultimately not even Dora could save Kafka from the eternal noise of the vampiric communications media. Despite Dora the ghosts were already winning, Kafka knew: they had already invented the telegraph, the telephone, and the wireless, and they would continue to thrive long after Kafka stopped writing letters and even long after he was dead.

Le smartphone, ou le dépeupleur : The lost ones (after Beckett)

JOHN ZILCOSKY: THREE BOOKS

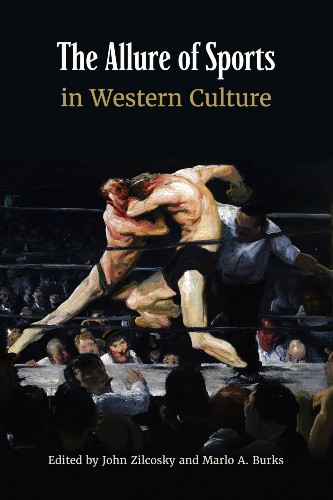

JOHN ZILCOSKY & MARLO BURKS, EDITORS: ‘THE ALLURE OF SPORTS’

‘In The Man Who Disappeared, Franz Kafka’s protagonist, Karl Rossmann, suffered a chokehold from a girl who knew jiu-jitsu. On Kafka and jiu-jitsu, see chapter 7.’

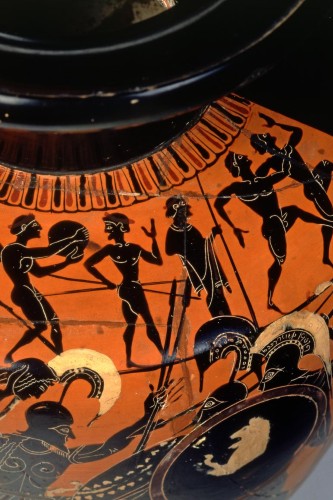

Hydria, Pentathlon (detail)

Attica, c.505BC

The Allure of Sports

Bellows, Stag at Sharkey’s, 1909

Footballeurs (detail)

Nicolas de Staël, 1952

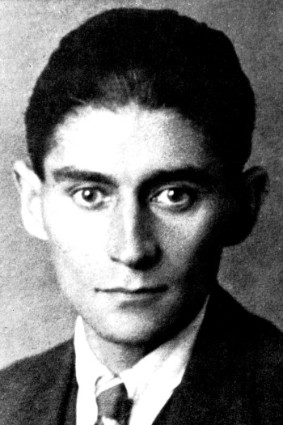

FRANZ KAFKA IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 2

After the sushi we play word association; when ‘law’ comes up I say ‘Kafka’. Konrád pulls out a pen and sketches a perfect replica of Three Runners. And thus we discover a common love for Franz.

Franz Kafka, Three Runners, 1912-13

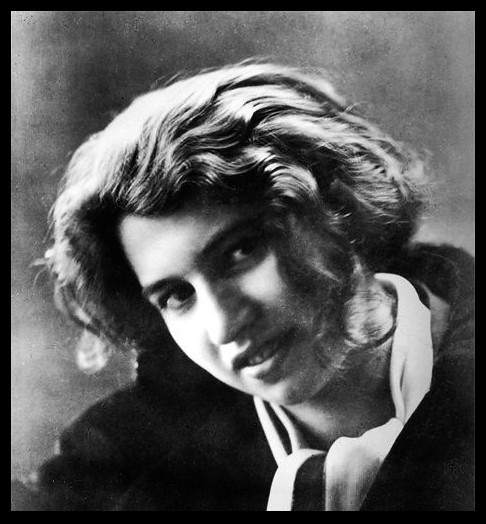

Everybody knows the story of Kafka and Milena, but nobody that of Franz and Dora Diamant: I tell it. The telling done, what moved them was not the air that cut like razor blades over Franz’s vocal cords nor the alcohol injections into his laryngeal nerves; neither was it the sister of mercy who made it her mission to ease his way to death. No, what moved them was how Kafka’s total absence of solemnity in his relationship with Dora contrasted with his tortured love for Felice and Milena. But what moved you and I was our notion of fragility, how it came about that the writer and insurance officer from Prague met the girl scaling fish in a Baltic kitchen; how that girl, having survived the Nazi fire and the Soviet frying pan, specified in her will that she be buried next to the man whose eyes saw everything.

Dora Diamant

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 13

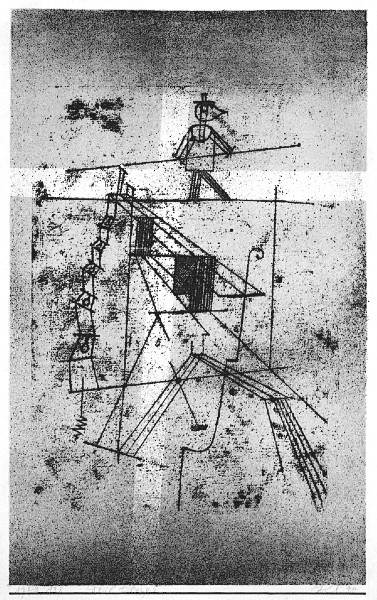

You and Mara scored a triumph with your Munich recording [of Kurtág’s Kafka-Fragmente], a triumph only outdone by your subsequent recitals. Is there enough variation now for you to make a comparison between your interpretations? Given the brevity of the pieces and the detail of the score, can one even speak of interpretation? The answer comes when I recall that every high-wire walker apprehends their fall in their own way, that every acrobat walks a tightrope differently. I think of my bedsit on Palmerston, the dark wood panelling, the damask wallpaper; I think of my lonely bed and late nights reading Franz: In becoming animal I became an artist.

Paul Klee, Tightrope Walker, 1923

Listen! The voice takes on an oboe-like drone while a tuning-peg glissando gives the violin a flute-like shimmer: In this music as in Kafka, there’s no place for complacency. I think of my bay window and the foreclosure of my future; I think of Franz’s answer to Felice when she asked him about his prospects: ‘Needless to say I have no plans, no prospects; I cannot step into the future’. Listen! The violin’s left-hand pizzicati; the voice, resonant and staccato. With Felice, Franz was insufferable in his suffering. How could he ever have imagined he could be happy as her husband? And yet he was always lucid: ‘On the pretext of wanting to free you of me, I force myself upon you’.

Felice Bauer

The better match was Milena: Franz just couldn’t overcome his fear.

Milena Jesenská

Listen! The paring away of the inessential, the sculptural purity of concentrated sound: Fragment after fragment confirms the depth of the music, the depth of the darkness the spotlight lays bare. Kafka at Goethe’s house, flirting for days with the keeper’s daughter: Is there a link between his success with Greta and his failure with Milena? Might not his ease with girls be the other side of the coin of his difficulty with women? Could it be that girls, simply by accepting him as he was, gave him a sense of unconditional love that sexuality precluded women from giving? However great his lucidity about the world, it was not as great as his yearning for intimacy, a lasting intimacy with just one woman who—as he wrote to Milena—would enfold him. I think of you, I think of how you enfold me, and I feel the world falling away beneath my feet at the thought that you’re leaving.

Kafka (29) with Greta Kirchner (15), Goethe House (Weimar), June 1912

Listen! Now fleeting as from afar, now full and familiar, the singer sings of two violinists making music in a tram speeding through the streets; now slow and sentimental, now fiery and free, the violinist plays, first on one violin, then on another: Capturing the charm of Kafka’s ‘Scene on a Streetcar’, the musicians remind us that all his life, Franz was moved by the most simple things. And I, Marietta, what moves me? I am moved by the child struggling to hold back his tears, not by the child who cries; I am moved by the dog on his last legs, his dignity when he steals away to die; I am moved by the wallflower who dances alone, not by the one who fades away. When you’re gone, I will try to be worthy of the child, the dog and the wallflower.

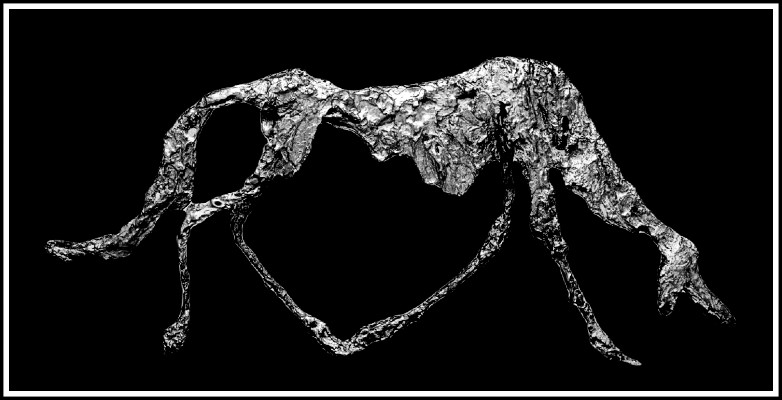

Alberto Giacometti, Dog, 1951

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG