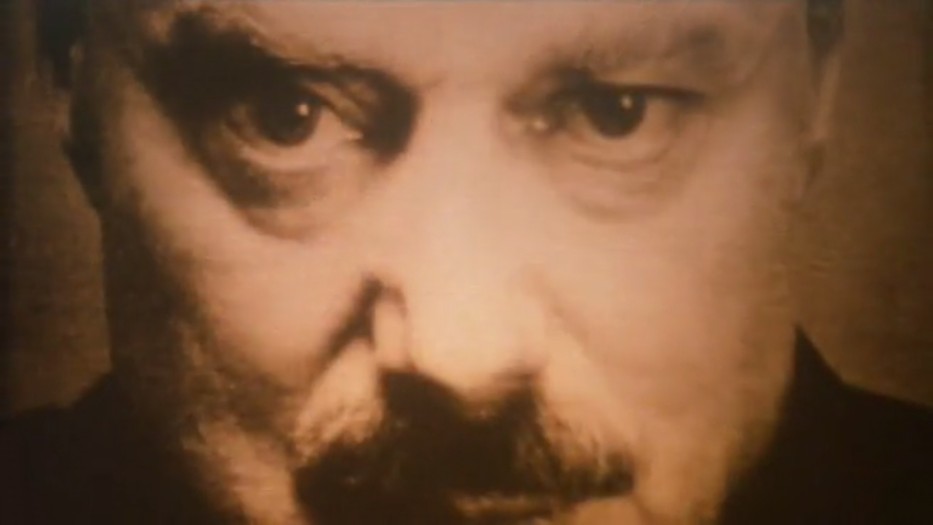

GEORGE ORWELL

NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR

SEXUAL FREEDOM AND POLITICAL FREEDOM: ON ORWELL’S ‘NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR’

BY CASS SUNSTEIN

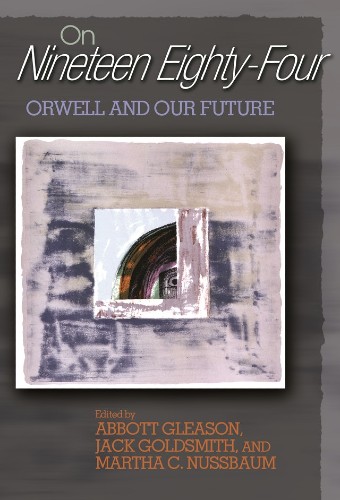

This is the full text of Cass Sunstein’s chapter, ‘Sexual Freedom and Political Freedom’ in A. Gleason et al., editors, On Nineteen Eighty-Four: Orwell and our Future (Princeton University Press, 2005) pp. 233-241.

POSTED BY KIND PERMISSION OF CASS SUNSTEIN

Cass Robert Sunstein is currently the Robert Walmsley University Professor at Harvard. He is the founder and director of the Program on Behavioral Economics and Public Policy at Harvard Law School. In 2018, he received the Holberg Prize from the government of Norway, sometimes described as the equivalent of the Nobel Prize for law and the humanities.

All images from 1984, dir. Michael Radford (Virgin Films, 1984)

Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

One of the most vivid passages in Nineteen Eighty-Four appears in the middle of the novel, where Winston experiences what is meant to be a moment of revelation. The passage can be found immediately after Winston tells Julia about ‘his married life’: as it happens Julia knew ‘the essential parts of it already.’ Thus she describes ‘to him, almost as though she had seen or felt it, the stiffening of Katharine’s body as soon as he touched her.’ This was ‘the frigid little ceremony that Katharine had forced him to go through on the same night every week.’ Winston notes that she ‘hated it,’ but ‘nothing would make her stop doing it.’ What Katharine called it, Winston says, Julia will ‘never guess’; but of course Julia ‘promptly’ guesses: ‘Our duty to the Party.’

Big Brother, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

Then Julia begins to ‘enlarge upon the subject’: It was not merely that the sex instinct created a world of its own which was outside the Party’s control and which therefore had to be destroyed if possible. What was more important was that sexual privation induced hysteria, which was desirable because it could be transformed into war fever and leader worship. The way she put it was: ‘When you make love you’re using up energy; and afterwards you feel happy and don’t give a damn for anything. They can’t bear you to feel like that. They want you to be bursting with energy all the time. All this marching up and down and cheering and waving flags is simply sex gone sour. If you’re happy inside yourself, why should you get excited about Big Brother and the Three-Year Plans and the Two Minutes Hate and all the rest of their bloody rot?’ This was very true, he thought. There was a direct, intimate connection between chastity and political orthodoxy.

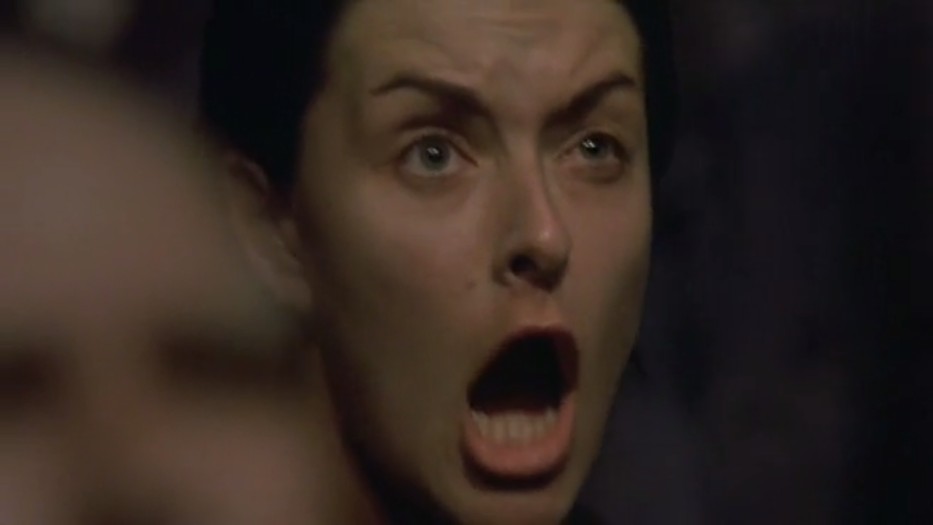

Two Minutes Hate, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

This passage lies at the core of Orwell’s stated account of sexuality, politics, and totalitarianism. We might discern from the passage a distinctive thesis: Totalitarian governments thrive on the repression of sexual drives; they repress sexuality in order to make room for mass ‘marching’ and public ‘cheering,’ that is, ‘sex gone sour.’ Nor is it hard to think of governments, and political movements, that appear to provide at least indirect support for Orwell’s claim. Consider, for example, highly eroticized political movements in America and elsewhere that thrive, at least in part, on the effort to combat sexual promiscuity, and that eroticize that very effort (sometimes by talking about sex so much).

Ingsoc party rally, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

My claim here, however, is that Orwell’s claim is wrong—that there is no ‘direct, intimate connection between chastity and political orthodoxy.’ The links between ‘sexual privation’ and ‘orthodoxy’ are much less direct and intimate, and sometimes the two are antagonists, not allies. Orwell’s treatment of the issue is diminished by the fact that Julia, most of all on this count, emerges as less a person than an adolescent male fantasy, a point that may also shed light on the weakness of the link that Orwell draws between sexual freedom and totalitarianism. Orwell has at most identified a mechanism, not a lawlike generalization.

Julia, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

The point has contemporary implications. Many people seem to share Orwell’s belief that political totalitarian and sexual repression march hand in hand, both logically and empirically. On this view, it is no accident that authoritarian nations—Afghanistan under the Taliban, for example, or communist China—are concerned both to crush dissent and to suppress sexual liberty. In free and less free countries, those who insist on the protection of sexual liberty (in such domains as prostitution and pornography) often claim to be political dissidents, or close cousins of political dissidents, and urge that they deserve the same degree of respect accorded to those who attempt to topple a politically repressive regime. Nothing that I say here will challenge efforts to reduce government interference with sexual liberty, nor will I explore the question of what, concretely, sexual liberty should be understood to be. But I will offer reasons to challenge current manifestations of the tendency to find a link between sexual repression and political repression. I do believe that there is a close association between political repression and the repression of women, but Orwell is, unfortunately, quiet on that score.

Winston’s arrest, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

To deal with the relationship between sexual privation and political orthodoxy, it will be useful to begin more generally with Orwell’s treatment of sex and love. This treatment superficially supports but actually outruns his own thesis about the purpose and effect of sexual frustration. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, sex is portrayed in several different ways. First, there is the dutiful, dead, frigid, antierotic, pro-Party sex of Winston’s marriage, contrasted with the much freer relationship between Winston and Julia. But an alternative account of sex is offered early in the novel, during the Two Minutes Hate. Here Winston has ‘vivid, beautiful hallucinations,’ involving ‘the dark-haired girl behind him.’ According to those hallucinations: ‘He would flog her to death with a rubber truncheon. He would tie her naked to a stake and shoot her full of arrows like Saint Sebastian. He would ravish her and cut her throat at the moment of climax. He hated her because she was young and pretty and sexless, because he wanted to go to bed with her and would never do so, because round her sweet supple waist, which seemed to ask you to encircle it with your arm, there was only the odious scarlet sash, aggressive symbol of chastity’. (Chancing upon her some seventy pages later, he notices ‘that by running he could probably catch up with her. He could keep on her track till they were in some quiet place, and then smash her skull in with a cobblestone’.) This is the ‘girl’ who turns out to be Julia. In their first real discussion, he tells her: ‘I wanted to rape you and then murder you afterwards. Two weeks ago I thought seriously of smashing your head in with a cobblestone’.

Julia and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

Of Orwell’s three portrayals of sex, the most conventional involves the relationship between Winston and Julia. Their initial physical encounter is notably unerotic: ‘At the beginning he had no feeling except sheer incredulity. The youthful body was strained against his own, the mass of dark hair was against his face, and yes! Actually she had turned her face up and he was kissing the wide red mouth. He had pulled her down on to the ground, she was utterly unresisting, he could do what he liked with her. But the truth was that he had no physical sensation except that of mere contact. All he felt was incredulity and pride. He was glad that this was happening, but he had no physical desire’. Later, after sexual intercourse: ‘Their embrace had been a battle, the climax a victory. It was a blow struck against the Party. It was a political act’. (Compare Julia’s activity, feigned to be sure, for the Junior Anti-Sex League.)

Julia and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

While there are a number of portrayals of sex in Nineteen Eighty-Four, there are only two love stories, involving two couples: Julia and Winston is one, and Winston and O’Brien the other; the most erotically charged, even intense scenes involve the latter. In a way the whole book is structured around a love triangle, in which O’Brien extinguishes the erotic connection between Julia and Winston, marking the triumph of the Party against a ‘blow’ that had threatened it, and re-establishing both chastity and political orthodoxy. (There is an obvious Oedipal dimension to the triangle, insofar as O’Brien is a kind of punitive father, splitting Winston from his beloved.)

O’Brien and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

The existence of a love triangle is signaled early on, where Orwell writes, of O’Brien, that Winston ‘felt deeply drawn to him, and not solely because he was intrigued by the contrast between O’Brien’s urbane manner and his prize-fighter’s physique. He had the appearance of being a person that you could talk to, if somehow you could cheat the telescreen and get him alone’. Winston has had a dream, or it might be real, in which O’Brien whispers to him: ‘We shall meet in the place where there is no darkness.’ And this becomes the foundation for the long concluding section, which is portrayed as a series of sexually sadistic acts committed by O’Brien against Winston. In fact it is a sustained scene of rape and castration. (This is why Nineteen Eighty-Four, as opposed to, say, Brave New World, belongs as much to the genre of horror as to that of science fiction.)

O’Brien and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

Early on in the torture, when O’Brien momentarily takes away the pain, Orwell writes that as Winston ‘looked up gratefully at O’Brien,’ ‘his heart seemed to turn over. He had never loved him so deeply as at this moment. Perhaps one did not want to be loved so much as to be understood. O’Brien had tortured him to the edge of lunacy, and in a little while, it was certain, he would send him to his death. It made no difference. In some sense that went deeper than friendship, they were intimates’. When the more severe torture begins, O’Brien announces, lest there should be any question about what kind of scene this is, ‘You will be hollow. We shall squeeze you empty, and then we shall fill you with ourselves’. As this torture starts, ‘O’Brien laid a hand reassuringly, almost kindly, on his. ‘This time it will not hurt,’ he said. ‘Keep your eyes fixed on mine.’ ‘The equipment produces in him ‘a large patch of emptiness, as though a piece had been taken out of his brain’.

O’Brien and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

That is the rape scene; the castration scene follows. O’Brien forces Winston to take off his clothes, and while Winston is naked, O’Brien ‘seized one of Winston’s remaining front teeth between his powerful thumb and forefinger. A twinge of pain shot through Winston’s jaw. O’Brien had wrenched the loose tooth out by the roots. He tossed it across the cell.’ Then he commands: ‘Now put your clothes on again’. It is almost anticlimactic when, in the famous ‘rats’ scene, O’Brien leads Winston to betray Julia.

O’Brien and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

The arc of the novel appears to fit well with Orwell’s thesis. The erotic connection between Julia and Winston produces a threat to the Party. O’Brien has to sever the link in order to transfer Winston’s erotic attention to Big Brother (thus Winston, in the final paragraphs, is portrayed as bride, grateful rape victim, repentant son, suckling infant: ‘He was back in the Ministry of Love, his soul white as snow.The long-hoped-for bullet was entering his brain. O stubborn, self-willed exile from the loving breast! He loved Big Brother’). There are pieces that do not quite fit; the relationship between Julia and Winston fuels, at least on Winston’s part, political activity rather than not giving ‘a damn for anything’, and in the end Winston is perhaps less a sexually frustrated marcher (though he does cheer: ‘he was with the crowds outside, cheering himself deaf’) than something hollowed-out and dead. But the basic picture seems to cohere.

O’Brien and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

Julia claims—and though this is not entirely clear, she seems to be speaking in Orwell’s voice—that if people are sexually active, they ‘feel happy and don’t give a damn for anything.’ Political orthodoxy is a consequence of sexual frustration, which governments can channel into marching and flag-waving and the Two Minutes Hate. Sexual satisfaction removes the taste for these forms of political participation; people will no longer ‘get excited’ once they are happy ‘inside’ themselves. (Compare: ‘Almost as swiftly as he had imagined it, she had torn her clothes off, and when she flung them aside it was with that same magnificent gesture by which a whole civilization seemed to be annihilated. Her body gleamed white in the sun’.) In short, political fevers are a product of sexual frustration, and this is one of the things that a totalitarian government knows best. (Compare Winston’s approval of the fact that Julia had been with scores of men; his desire for her to have been with ‘hundreds—thousands’; his claim ‘I hate purity. I hate goodness. I don’t want any virtue to exist anywhere’; his pleasure at her reaction to his question about her attitude toward the sex act itself, ‘I adore it’: ‘Not merely the love of one person, but the animal instinct, the simple undifferentiated desire: that was the force that would tear the Party to pieces. He pressed her down upon the grass’.)

Julia and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

It is not easy to know how to test Orwell’s thesis, which appears to be an empirical claim. But there are obvious problems. Many people who are sexually inactive, voluntarily or as a result of coercion, do not support the prevailing political orthodoxy. Why should we think that ‘hysteria,’ if that is what is induced by sexual deprivation, leads to approval of the political status quo? It is at least as plausible to think that sexual activity would lead to political rebelliousness as to believe that it is correlated with conformity. Some dissident groups take steps to repress sexual activity, sometimes with the thought that the repression will strengthen ties to the cause and hence further endanger the state. Or—to me more plausibly—it may be that the sort of people who are sexually active are often likely to be political rebels. In any case is it really true that sexual satisfaction makes people—in Julia’s words—not ‘give a damn for anything’? This seems implausible. Perhaps some people who are immersed in an extremely passionate relationship do not like to think about anything else; but that is a different point.

Julia and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

Notice in this connection that before O’Brien’s true nature is revealed, Winston and Julia, now sexual partners, do not abstain from politics but on the contrary enlist in what they think is a conspiracy against the Party. The conspiracy is one in which sacrifice for the cause—with one exception—is unlimited, in fact not so different, with that exception, from what the Party wants from its citizens:

‘You are prepared to give your lives?’

‘Yes.’

‘You are prepared to commit murder?’

‘Yes.’

‘To commit acts of sabotage which may cause the death of hundreds of innocent people?’

‘Yes.’

‘To betray your country to foreign powers?’

‘Yes.’

‘You are prepared to commit suicide, if and when we order you to do so?’

‘Yes.’

‘You are prepared, the two of you, to separate and never see one another again?’

‘No!’ broke in Julia.

The single exception embodied in Julia’s ‘No!’ shows that political loyalty can be undermined by an erotic relationship. But this is a quite different point from Orwell’s thesis.

Julia and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

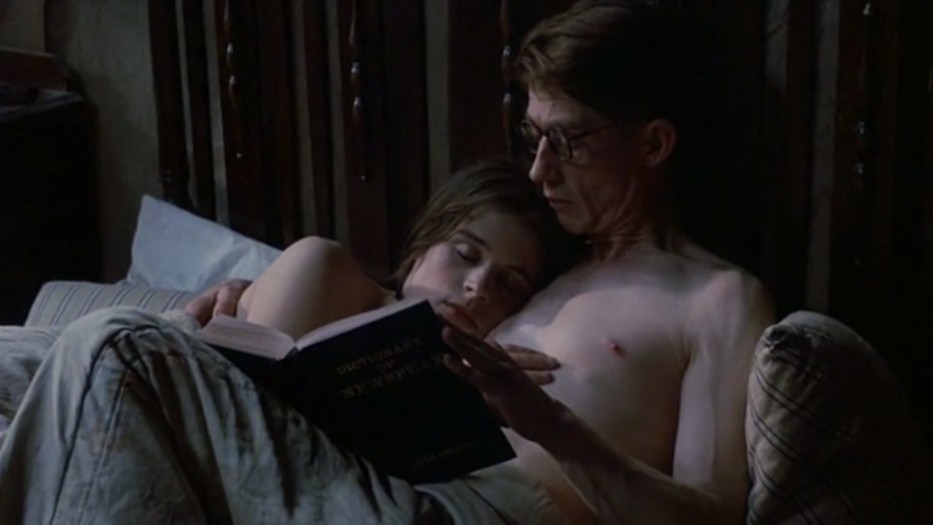

We might compare in this regard the very different presentation of the relation between sexual freedom and political freedom in Huxley’s Brave New World. There sexual promiscuity is a kind of opiate of the masses, consistently encouraged partly in order to discourage political rebellion. Both novels portray the death of the individual soul, but with major differences: Where Nineteen Eighty-Four is a nightmare vision of Communism or Fascism, Brave New World is a nightmare vision of triumphant capitalism. We might even identify a Huxley hypothesis, one that appears to compete directly with Orwell’s: Sexual activity diverts people from engaging in political causes, and it ought therefore to be encouraged by a government that seeks a quiescent population. On this view, sexual promiscuity is depoliticizing, soul-destroying, a twin to soma, antagonistic to rebellion. Some political movements have in fact accepted this view, and it is easy to see how it might be true. We can imagine the possibilities described in the accompanying matrix.

Sexual Repression versus Sexual Freedom

On this view, Huxley’s hypothesis is the antonym to Orwell’s. But along one dimension, it is only apparently competing. The key point is that Huxley, like Orwell, identifies sexual activity with political passivity. In Orwell, the state seeks marching, even a form of fanaticism; in Huxley, the state seeks a kind of pleased, vacant indifference. Sexual repression is, in Nineteen Eighty-Four, a necessary way of ‘bottling down some powerful instinct and using it as a driving force’; in Brave New World, the society is infantilized and pacified through catering to that same instinct. Thus it is that in Orwell’s world, a form of sex that is not a ‘frigid little ceremony’ is a threat to the political order, whereas in Huxley’s, the threat comes from a refusal of sex, or of soma, which will be and will produce rebellion. Compare Winston to Julia, who appears to have little interest in politics, and who says, ‘I’m not interested in the next generation, dear.’ When Winston says, ‘You’re only a rebel from the waist downwards,’ she does not object but instead finds the statement ‘brilliantly witty’.

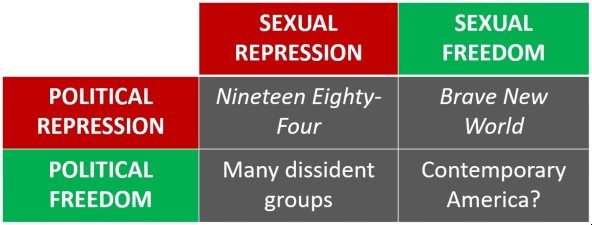

Julia, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

But there are other possibilities, very different from Orwell’s and Huxley’s shared view. It may be that sexual love can actually fuel political activity, by expanding the imagination and promoting empathic engagement with the lives of others. Probably we need to distinguish here, as Orwell does not, among different kinds of sexuality. It is not as if there is a choice only between ‘the Party’s sexual puritanism’ and ‘sexual privation’ (Orwell’s phrases) on the one hand and ‘making love’ on the other. Promiscuous relationships are not all the same; nor are enduring, passionate relationships. Promiscuous relationships may have different effects from enduring, passionate relationships. The connection between any one of these and political activity depends on many independent variables.

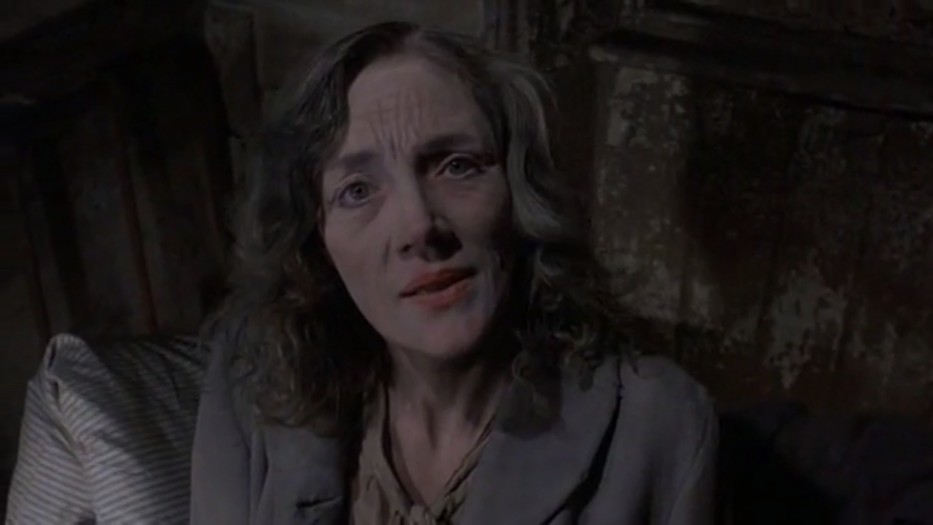

The prostitute, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

All this may not be quite fair to Orwell. He also seems to have another point in mind. It has to do with how sexuality is connected with individuality and self-expression, with the rejection of conformity, with what he seems to see as the truest and most distinctive self, anarchic and not governable. It is this that presents the deepest danger to the Party. Orwell is not speaking here of love or of intimate relations with individual persons: ‘Not merely the love of one person, but the animal instinct, the simple undifferentiated desire: that was the force that would tear the Party to pieces’. Here, too, there is an interesting relationship with Huxley, who portrays promiscuity as soulless, as an erasure of individuality, as a form of conformity. Both Huxley and Orwell may have a particular conception of authentic sexuality in view, and they may not be so different. The contrast is that Orwell portrays ‘the animal instinct, the simple undifferentiated desire’ as active and a threat to political orthodoxy, something that, once unleashed, will lead to rebellion. O’Brien appears to agree. Winston’s torture and castration produce a kind of docility, even serenity, that paves the way for, or that is, acceptance of Big Brother and death.

Julia and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

Orwell’s conception of sexuality as an ‘animal instinct,’ and as an expression of something ungovernable and personal, may be right; certainly there is truth in it. But sexuality can itself be a product of social practices; it should not be naturalized, and opposed, as ‘true self,’ to cultural constraint. We do not know the extent to which sexual drives are themselves a product of private and public authority. Orwell tends to naturalize the ‘sex instinct’ (as the very term suggests). This is an under-explored point in the novel itself, where sexual drives seem to be something beyond the reach of politics or the Party, except through after-the-fact techniques of the kind used by O’Brien. Perhaps this is not Orwell’s full position; Winston’s early fantasies of sexual violence might be taken as a product of the particular social circumstances of Party domination. But this point is not much elaborated, nor is it brought into contact with Julia’s claims about the nature and consequence of sexual activity.

The prostitute, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

Does a free society allow prostitution and pornography? Does a free society attempt to eliminate ‘sexual repression,’ understood as state interference with people’s sexual choices? Much will depend on how we understand the idea of sexual liberty. Perhaps that form of liberty does not require mere freedom from governmental restraints. If preferences and values have social origins (at least in part), then the desire to go to a prostitute, or to be a prostitute, may reflect a lack of freedom. Notwithstanding this point, many contemporary critics do connect sexual freedom and political freedom. They seem to think that those who challenge sexual repression, or sexual orthodoxy, are in some sense striking a blow for political liberty as well.

The prostitute, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

If the discussion here is correct, the claimed link is illusory. Sexual freedom, at least in Orwell’s sense, need not be connected with political freedom, and those who seek the one need have no interest in the other. There is no link logically or empirically. In some ways Orwell’s conception of their relationship is a cousin of the conception of many dissident movements in the 1960s. Those movements combined an intense interest in sexual experimentation with an intense interest in political rebellion; they were a self-conscious challenge to conformity in various guises. But it is no coincidence that modern feminism outgrew those movements, in part because sexual liberty was understood, much of the time, as a matter of giving men greater sexual access to women. While I cannot support the claim here, I think that Orwell’s conception of sexual freedom belongs in the same family, and indeed that sexual equality is a large neglected topic in a book that otherwise has so much to say about both freedom and sex.

Julia eyeing Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

Orwell suggests that totalitarian governments favor ‘sexual puritanism,’ which induces ‘hysteria,’ something that such governments mobilize in their own favor. This is the image of patriotic frenzy as ‘sex gone sour.’ On this view, sexual freedom embodies freedom and individualism, and it is the deepest enemy of a totalitarian state. A state that allows sexual freedom will be unable to repress its citizens. This is why O’Brien must achieve victory over Julia.

Julia, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

But it is possible to imagine other, equally plausible views. ‘Sexual privation’ might indeed induce hysteria, but of the sort that leads to rebellion and thus serves as an obstacle to a successful totalitarian government. I have suggested that in the face of existing social norms, many people who are sexually active are also likely to be political rebels, because of something in their character (itself perhaps a product of early childhood or genetic predispositions). And sexual freedom, even promiscuity, might be encouraged by totalitarian governments, in order to divert the citizenry and to induce apathy. (This is Huxley’s thesis.) Or we might reject the idea that the only two options are ‘privation’ and ‘freedom’ (as understood by both Orwell and Huxley). The real question might be what sorts of intimate relationships people are allowed to make with one another.

Julia and Winston, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

In the end I believe that Orwell’s thesis is a crude, vaguely Freudian cliché, implausible as an abstraction and in some ways undermined by the novel itself. It is true that some totalitarian states have attempted the approach he describes, and perhaps they have had some modest success. But Orwell was wrong to think that there is a ‘direct, intimate connection between chastity and political orthodoxy.’ The mechanisms that link sexual freedom and political freedom are extremely diverse. There are no law-like generalizations here.

The Ministry of Truth, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell / Radford

ORWELL’S ‘1984’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 14

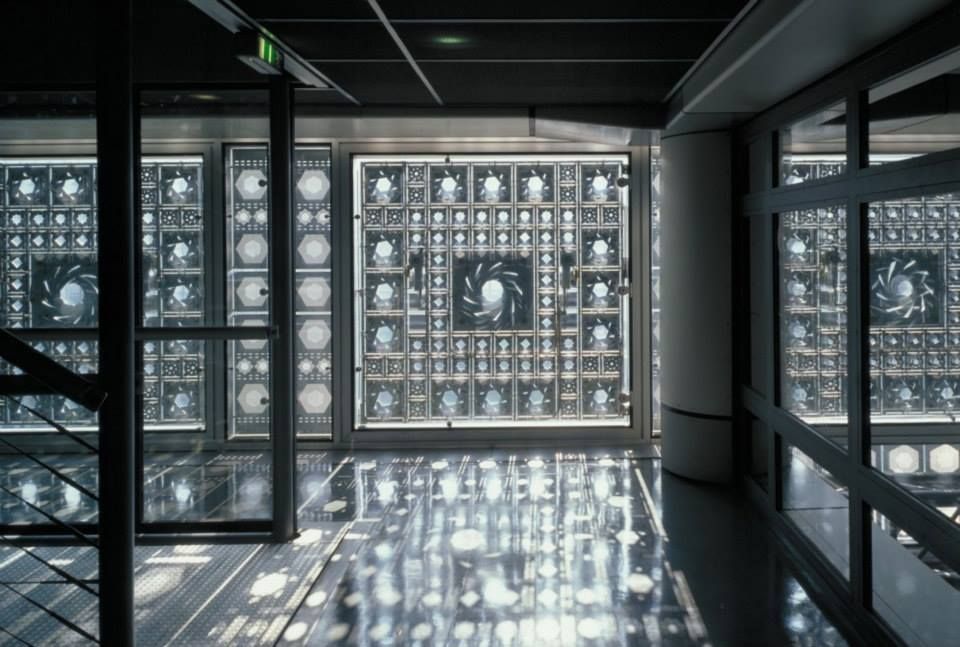

Underfoot, overhead, left, right, behind, ahead: Omnipresent, metal and glass conspire to remove all our bearings; unmoored, we ascend in spidery space. In a riot of shadow and light the guts of the construction invade our vision; reaching for your hand I catch your gaze: In the depths of your eyes as our hands entwine, I see Winston and Julia about to commit sexcrime.

Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris | © IMA / Fabrice Cateloy

Glass walls, polished floors; glowing columns, gleaming doors: Refracting, reflecting, surfaces shimmer with patterns of filtered light. And then it appears, a giant screen of geometric forms, a riot of proliferating motifs: Intensely-patterned panes unfold their symmetry. Look! Mirror-plates in meticulous rhythm, flashes of prudence and vanity; clockwork in crystal panels, wheels of time and fortuity.

̶ Come!

You take my hand, and through filigreed light lead me.

Institut du Monde Arabe, south façade, interior

On the rooftop, in the corridor between the empty restaurant and the Seine façade of the building, cubic modules of wicker furniture stack up in disorderly columns. Bearing witness to winter, Arabic urns of barren earth punctuate the passage. We slip in between two stacks of chairs and wend our way to the railing. Spinning around, you say:

̶ Take off your coat.

In the dark groves of your eyes sulphur butterflies swarm; ready to do what must be done, I shake my jacket from my shoulders and toss it onto a railing post. You slip off yours and sling it over mine. Turning your back to the garde-fou, you pull me towards you.

̶ Fuck me.

Bringing your hand to my crotch, you rub.

̶ Fuck me, Sprague!

The fire in your eyes shames the uncertain sun; the risk is calculated, let it be done: Bending you over the railing, I slip my hand between your legs. Your lush ripeness hardens me as I heave rhythmically.

̶ Go down and kiss it.

A sharp tug on your belt releases the pin; I fall to my knees, open your jeans and pull them down. Warm, wet and feral, at once lulling and unsettling, your sex beckons. I pull down your panties.

IMA terrace

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A novel by Richard Jonathan

GEORGE ORWELL: TWO PHOTOS & A BOOK ON ‘1984’

VIDEO: ‘SEXCRIME (1984)’ – EURYTHMICS (Live, 1987)

Sexcrime (1984) – Eurythmics (Live, 1987)

LYRICS: ‘SEXCRIME (1984)’ – EURYTHMICS

Can I take this for granted

With your eyes over me?

In this place, this wintery home

I know there’s always someone in

Sexcrime, sexcrime…

Nineteen eighty-four…

And so I face the wall

Turn my back against it all

How I wish I’d been unborn

Wish I were unliving here

Sexcrime, sexcrime…

Nineteen eighty-four…

I’ll pull the bricks down

One by one

Sexcrime, sexcrime…

Leave a big hole in the wall

Just where you are looking in

Sexcrime, sexcrime…

VIDEO: ‘1984’ – DAVID BOWIE (Live, 1974)

‘1984’ –David Bowie (Live, 1974)

LYRICS: ‘1984’ – DAVID BOWIE

Someday they won’t let you, now you must agree

The times they are a-telling, and the changing isn’t free

You’ve read it in the papers, and the tracks are on TV

Beware the savage jaw of 1984

They’ll split your pretty cranium, and fill it full of air

And tell that you’re eighty, but brother, you won’t care

You’ll be shooting up on anything, tomorrow’s never there

Beware the savage jaw of 1984

Come see, come see, remember me?

We played out an all-night movie role

You said it would last, but I guess we enrolled

In 1984 (who could ask for more?)

1984 (who could ask for more?)

(More…)

I’m looking for a vehicle, I’m looking for a ride

I’m looking for a party, I’m looking for a side

I’m looking for a reason that I knew in ‘65

Beware the savage jaw of 1984

Come see, come see, remember me?

We played out an all-night movie role

You said it would last, but I guess we enrolled

In 1984 (who could ask for more?)

1984 (who could ask for more?)

(More…)

1984…