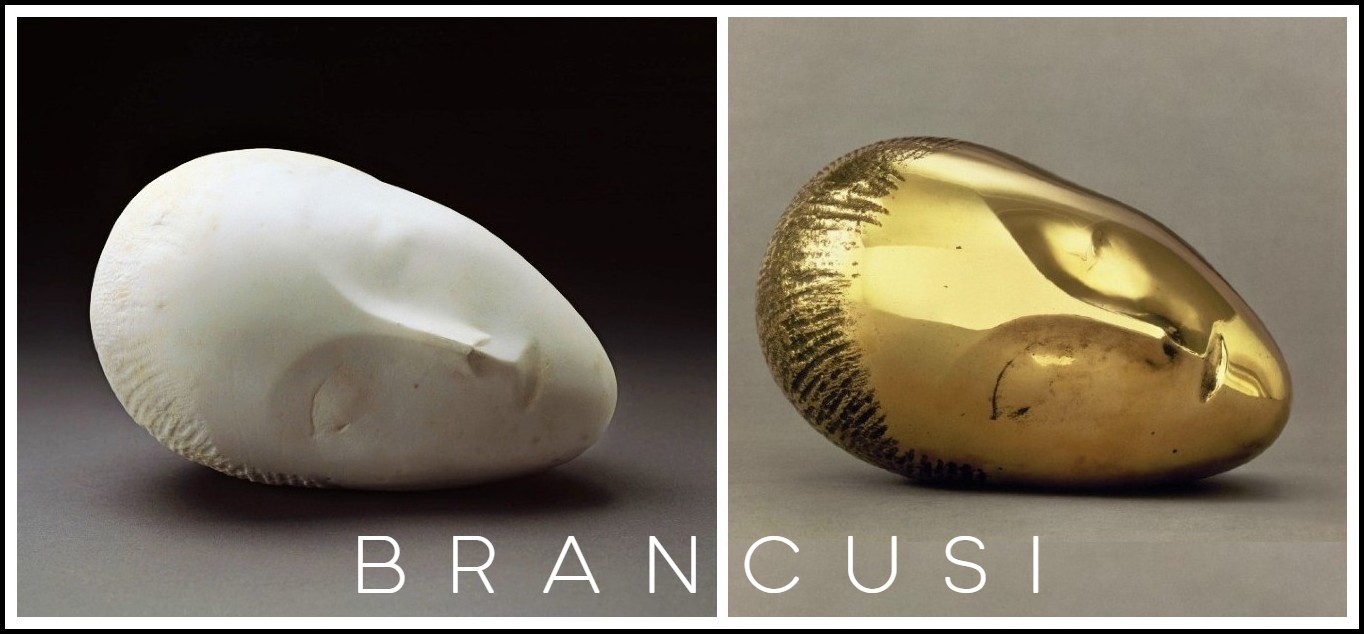

Henry Moore: On Sculpture | Holes

I. HENRY MOORE ON SCULPTURE | II. HENRY MOORE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’ | III. THE HOLES OF HENRY MOORE

I. HENRY MOORE ON SCULPTURE

From Henry Moore & John Hedgecoe, Henry Moore: My Ideas, Inspiration and Life as an Artist (London: Ebury Press, 1986)

John Hedgecoe – Henry Moore

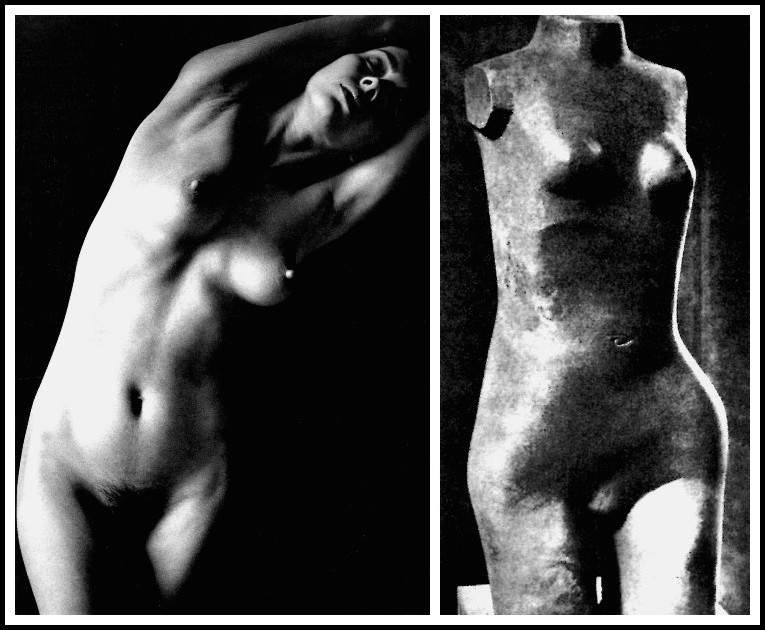

The human form has always been my main concern. It’s what we know most about —the softness and slackness of flesh, the hardness of bone, all the energy that is pent up in our own bodies. The early Greeks understood that and it came from their deep understanding and close observation of the human figure, so when they carved their sculpture it was with vision, understanding and sensitivity. That is why the best Greek sculpture is so good. They knew what was beneath the surface, so were able to release the life force which gave an added strength and vitality to their work. There is a deeper truth to be found in the knowledge of sculpture than in just the appearance of a sculpture.

John Hedgecoe – Henry Moore

For me a work must first have a vitality of its own. I do not mean a reflection of the vitality of life—movement, physical action of a dancer or spontaneous action. A work of sculpture can have in it a pent-up energy, an alert tension between its parts, an intense life of its own, independent of the object it may represent. When a work has this powerful vitality, we do not connect the word beauty with it. In my work I do not aim at beauty in the later Greek or Renaissance sense. Between beauty of expression and power of expression there is a difference of function. The first aims at pleasing the senses; the second has a spiritual vitality which for me is more moving; it goes deeper than the sense.

John Hedgecoe – Henry Moore

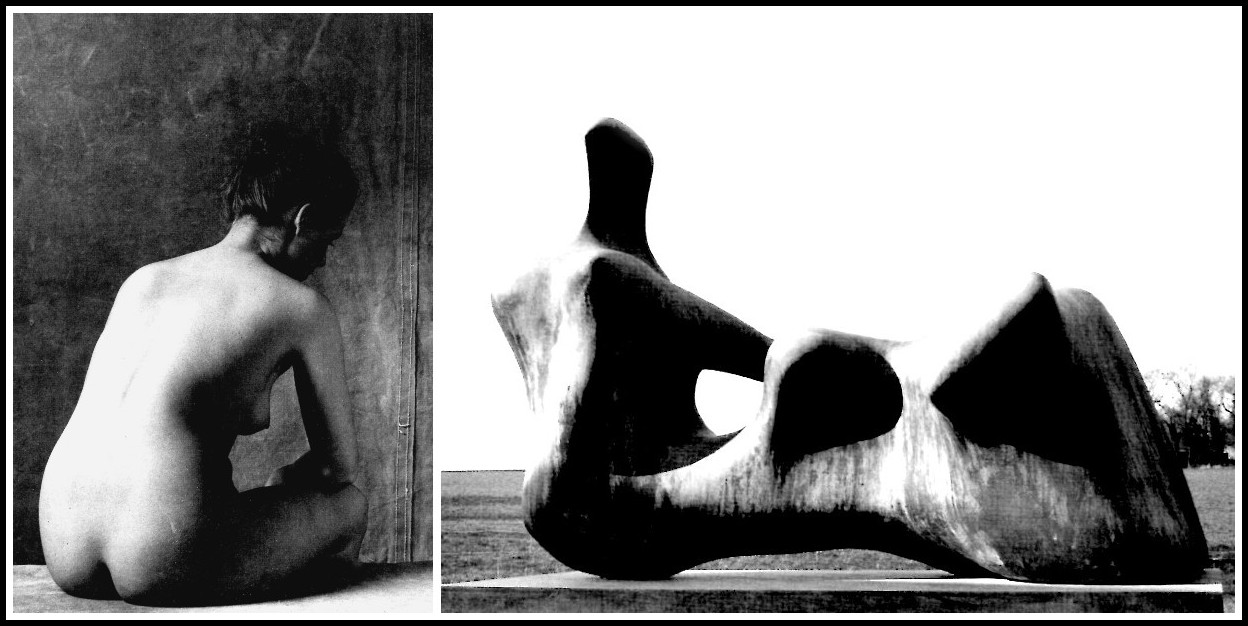

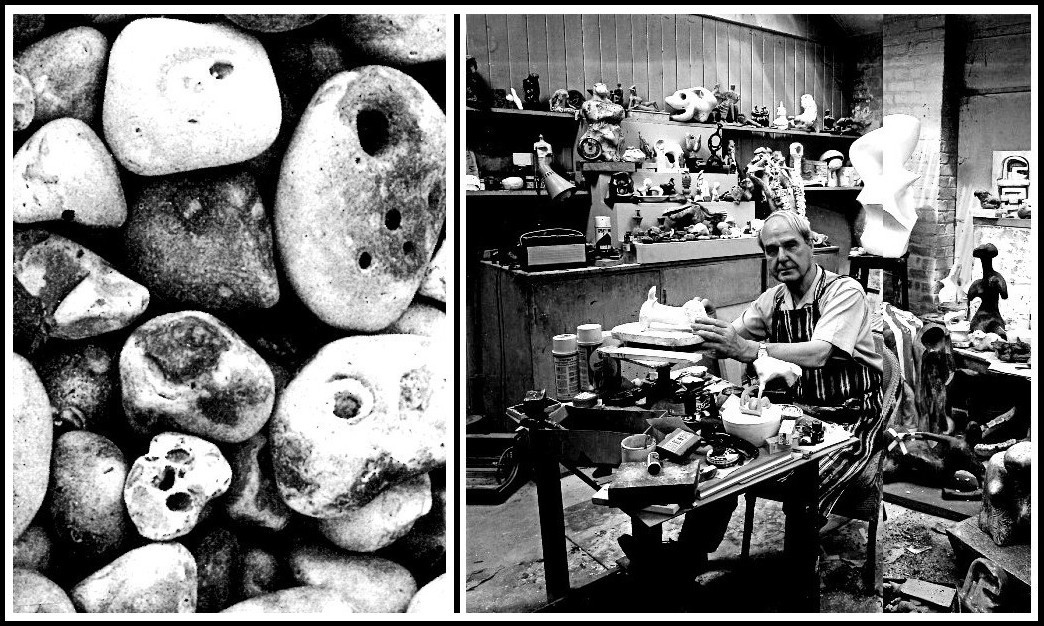

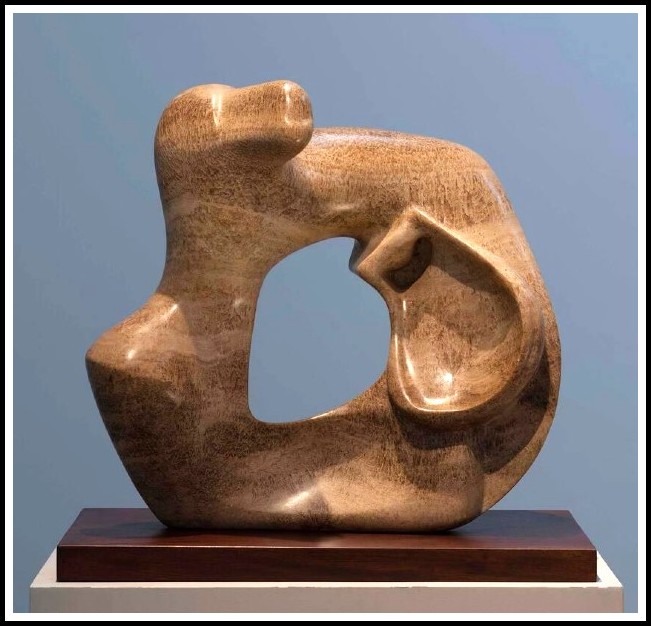

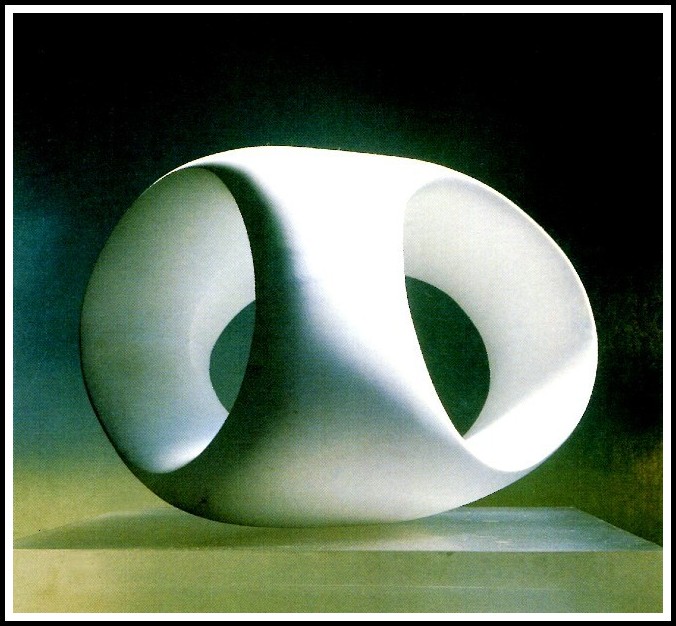

I liked carving stone sculpture because it was restrained, restricted and had to synthesize form and shape. But, after a time, I began to realize that it was preventing me from including the full three-dimensional world with air around it, so I began to make holes in sculpture to make the back have a connection with the front. A hole can have as much meaning as a solid mass—there is a mystery in a hole in a cliff or hillside, in its depth and shape. My idea was that I was trying to make the sculpture as fully realized as nature, not just two reliefs. For me, this was a revelation, a great mental effort. It was having the idea to do it that was very difficult, not the physical effort.

John Hedgecoe – Henry Moore

In my collection of found objects in my studio—stones, pebbles, bones, pieces of wood—for me they are all interesting shapes though some may find them exaggerated or distorted. But you must have some interest. You don’t want a perfect ball or a perfect square because then there’s no surprise. Anyway, I’m not sure what perfection is. A perfect circle drawn with a pair of compasses isn’t really perfect when looked at closely —the pencil wears out after it gets half way round and the line would get thicker. What I have tried to do is to evaluate and appreciate form for its own sake, for its own character. You can pick up an object, a pebble say, and give it a ‘meaning’ —of course, a pebble itself doesn’t have any meaning. One doesn’t quite know how ideas have been generated or where they come from. Sometimes one is influenced by a particular pebble or other natural form, but it’s equally possible to sit down with a blank sheet of paper and a pencil and a scribble will turn into something which is worth developing. It depends on how much background you have to draw on. The older you are, the more observant you are of the world, of nature, and forms; and the more easily can you invent. But it has to come from somewhere in the beginning, from reality, nature. Space, distance, landscape, plants, pebbles, rocks, bones, all excite me and give me ideas.

John Hedgecoe – Henry Moore

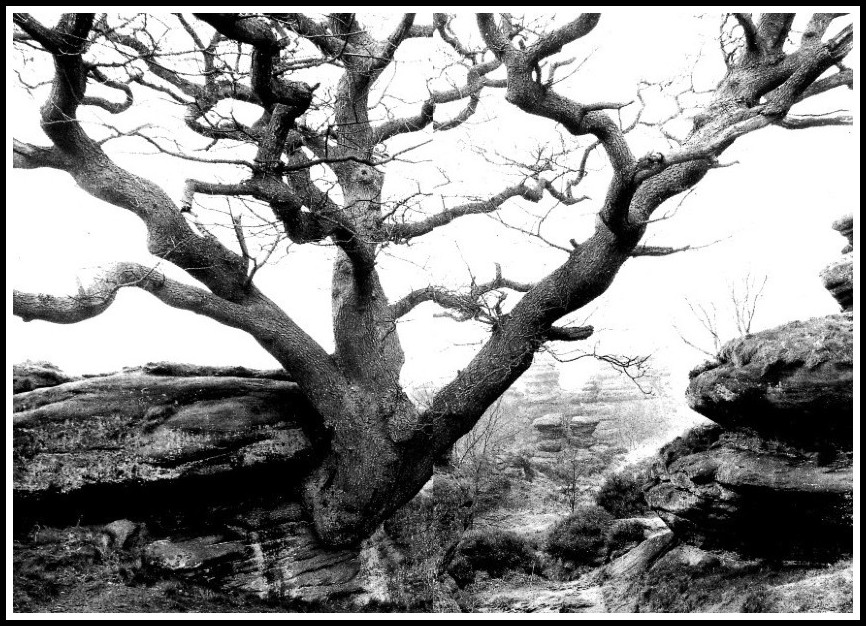

Nature produces the most amazing varieties of shapes, patterns and rhythms. What we see with our eyes has been added to by the use of the camera, the telescope and the microscope. This observation enlarges the sculptor’s vision. But merely to copy nature is no better than copying anything else. It is what use the artist makes of his observations by giving expression to his personal vision and from his study of the laws of balance, rhythm, construction, growth, the attraction and repulsion of gravity—it is how he applies all of this to his work that is important.

John Hedgecoe

Sometimes nature, in overcoming environmental factors, produces growth of an unusual kind. This asymmetrical response of trees and plants where there is insufficient space or sunlight has always interested me. If a tree needs more light, the branches will change direction; if a branch is cut off, it will be sealed and contained. I am trying to add to people’s understanding of life and nature, to help them to open their eyes and to be sensitive. Nature is inexhaustible. Not to look at and use Nature in one’s work is unnatural to me. It’s been enough inspiration for two million years—how could it ever be exhausted?

John Hedgecoe

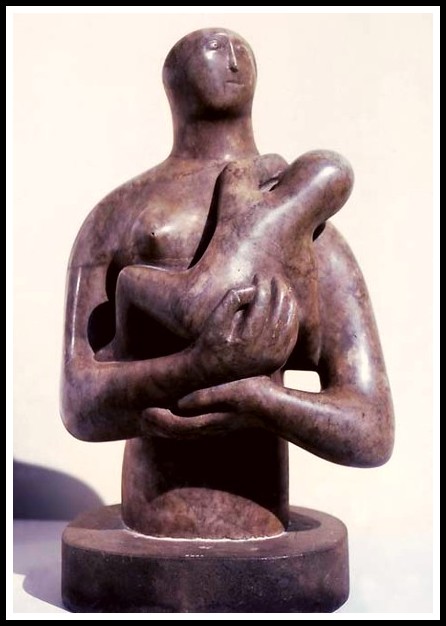

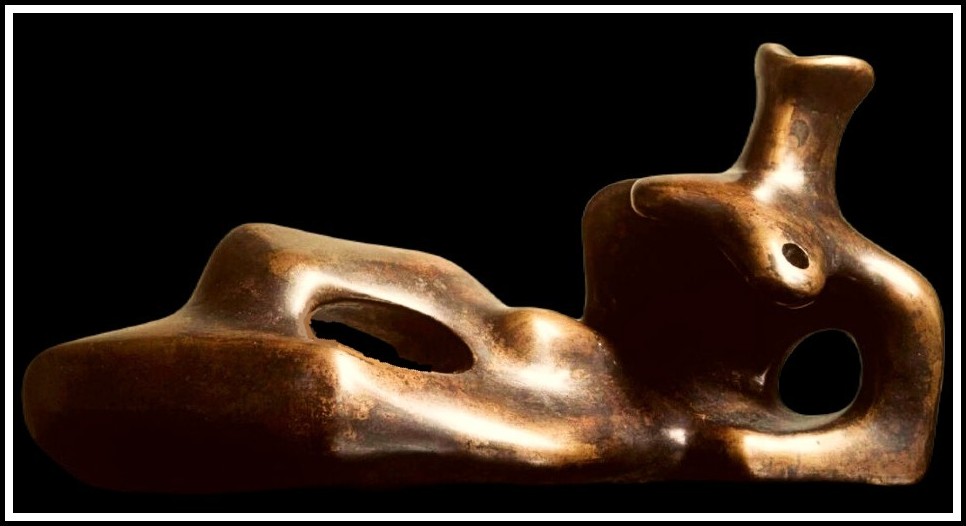

When I came to do my Madonna and Child, I spent a lot of time and thought on it. It was different in a way from the Mother and Child work I’d done before though, of course, there were many similarities, too. You have to have a big form protecting a little form. From very early on I had had an obsession with the Mother and Child theme—it has been a universal theme from the beginning of time and some of the earliest sculptures we’ve found from the Neolithic Age are of a mother and child. I discovered, when drawing, I could turn every little scribble, blot or smudge into a Mother and Child. (Later on I did the same with the Reclining Figure theme!) But, with the Madonna and Child, there was the religious element too, it was to strengthen religious beliefs. Nor did I want to create something which the average person would find dreadful or wrong. I tried to fit in with the accepted faith. It was a real worry, and gave me many problems. One lay in trying to make the child an intellectual-looking child, that you could believe might be more than just an ordinary baby. The Madonna’s face has a certain aloof mystery.

Henry Moore, Madonna & Child, 1943-44

Every sculpture should have its different problems. They may not be technical ones, they may well be human problems—trying to understand some part of human nature that previously you didn’t. All good art demands an effort from the observer. You shouldn’t think that a piece of art explains itself entirely without putting a mind to it at all. In fact, all art should have some more mystery meaning to it than is apparent to a quick observer. In my sculpture, explanations often come afterwards. I do not make a sculpture to a programme or because I have a particular idea I am trying to express. While working, I change parts because I do not like them not because of a kind of literary logic, but because I am not satisfied with form. Afterwards, I can explain or find reasons for it but that is rationalization after the event and the explanations were not at all in my mind at the time—not consciously anyway.

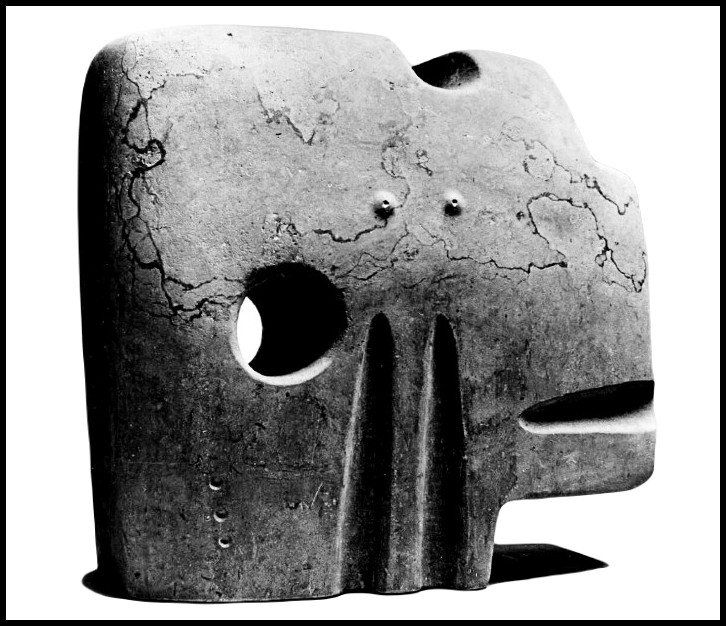

Henry Moore, Square Form, 1936

Generally, my sculptures have begun with a small maquette taken from a preliminary drawing. Drawing is a way of developing ideas more quickly than making something in three dimensions. You can draw a standing figure in two minutes, whereas to make it, it would take you at least an hour or two. Even a small carving would take a week. When my sculpture was mainly carving I would get rid of ideas, as it were, by drawing them to prevent them from blocking each other up. So, if a drawing interests me, I make it into a small maquette so that I can view it from every angle with ease simply by turning it in my hands. From this maquette, I would then decide whether to do a larger version which would entail some further alterations, because although a sculpture might work in a small size, as you enlarge it, it is necessary to change it again in order to get the scale, the proportion right. It’s a practical consideration. You don’t think about it, you just make it look more right. I might then carve it in wood or in stone, or make a working model by building an armature and then have it cast in bronze.

At one time whenever I made drawings for sculpture I tried to give them as much the illusion of real sculptures as I could—that is, I drew by the method of illusion, of light falling on a solid object. But I now find that carrying a drawing so far that it becomes a substitute for sculpture either weakens the desire to do the sculpture, or is likely to make the sculpture only a dead realization of the drawing. I now leave a wider latitude in the interpretation of the drawings I make for sculpture, and draw often in line and flat tones without the light and shade illusion of three dimensions; but this does not mean that the vision behind the drawing is only two-dimensional.1

1 – This paragraph is from a different source: Henry Moore quoted in Herbert Read, Henry Moore (London: Thames & Hudson, 1965) p. 138

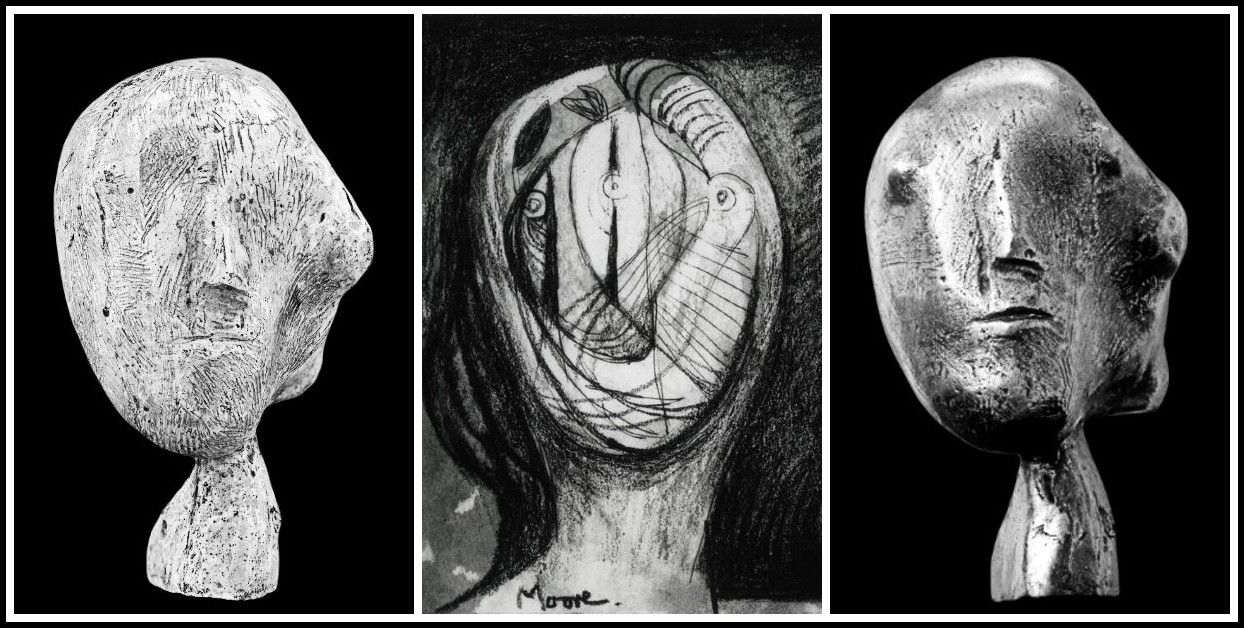

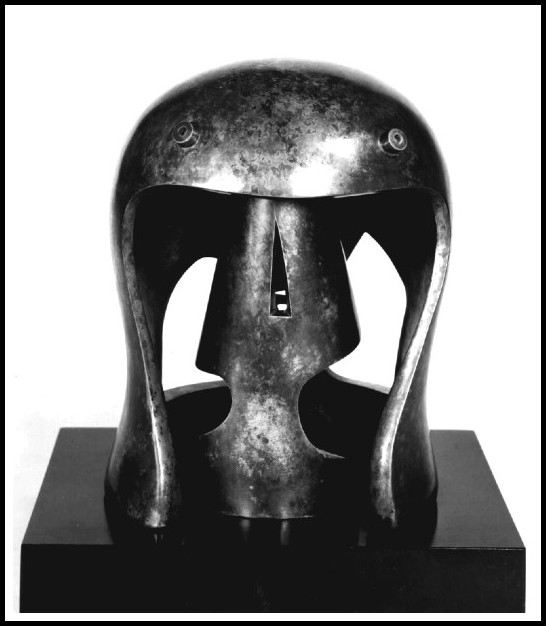

Henry Moore, Head, 1981 (plaster | drawing | bronze)

When working in plaster for bronze I need to visualize it as a bronze, because on white plaster the light and shade acts quite differently, throwing back a reflected light on itself and making the forms softer, less powerful, even weightless. At first I used to have a tremendous shock going from the white plaster model to the finished bronze sculpture. But after forty years of working in plaster for bronze I can now visualize what is going to happen. The main difference is that bronze takes on a density and weight altogether unlike white plaster. Plaster has a ghost-like unreality in contrast to the solid strength of the bronze. If I am not absolutely sure of what is going to happen when the white plaster model is cast into bronze, I paint it to make it look like bronze. After a sculpture is cast it’s too late, of course, to make any big alterations. I use a foundry in London for the medium- and life-size sculptures, but I now go to Noack in Berlin for the really big ones. I like a bronze to come back from the foundry clean and bright like a new penny. From then on it is possible, by the use of various chemicals, to give it a patina which helps its sculptural form. Bronze is a material which can be changed to any colour as well as being able to be highly polished. Clean air will turn it green, as seen on country church roofs. Nearer the sea the salt makes it greener still. In cities the smoke and carbon dioxide tend to make it black.

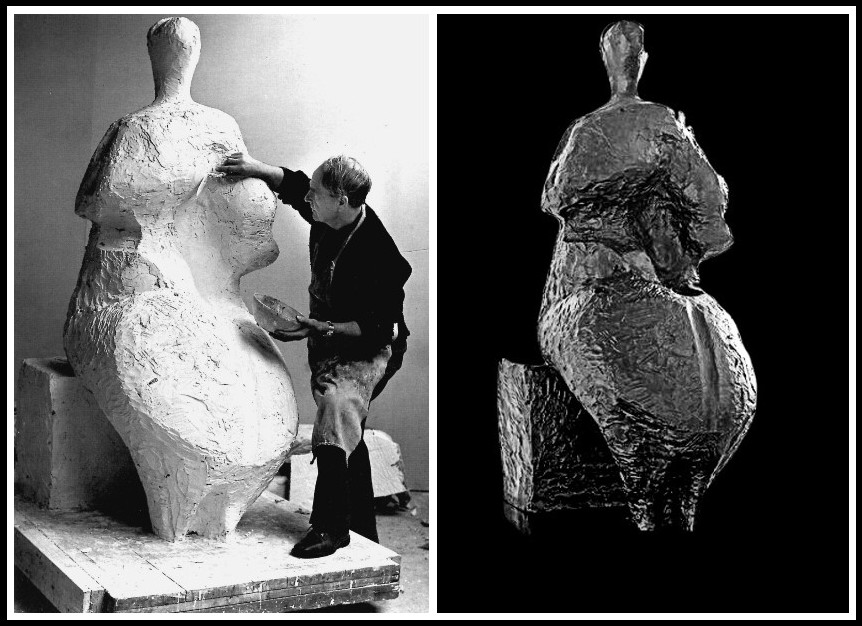

Henry Moore, Seated Woman, 1958-59 (plaster | bronze)

In a figurative sculpture, the head is, for me, the vital unit. It gives scale to the rest of the sculpture and, apart from its features, its poise on the neck has tremendous significance. Michelangelo’s faces are probably the least dominating part of his sculpture, for he was not a portraitist. In my opinion, individual features are not of the utmost importance in sculpture, whilst their proportion and placing in the head can have enormous meaning.

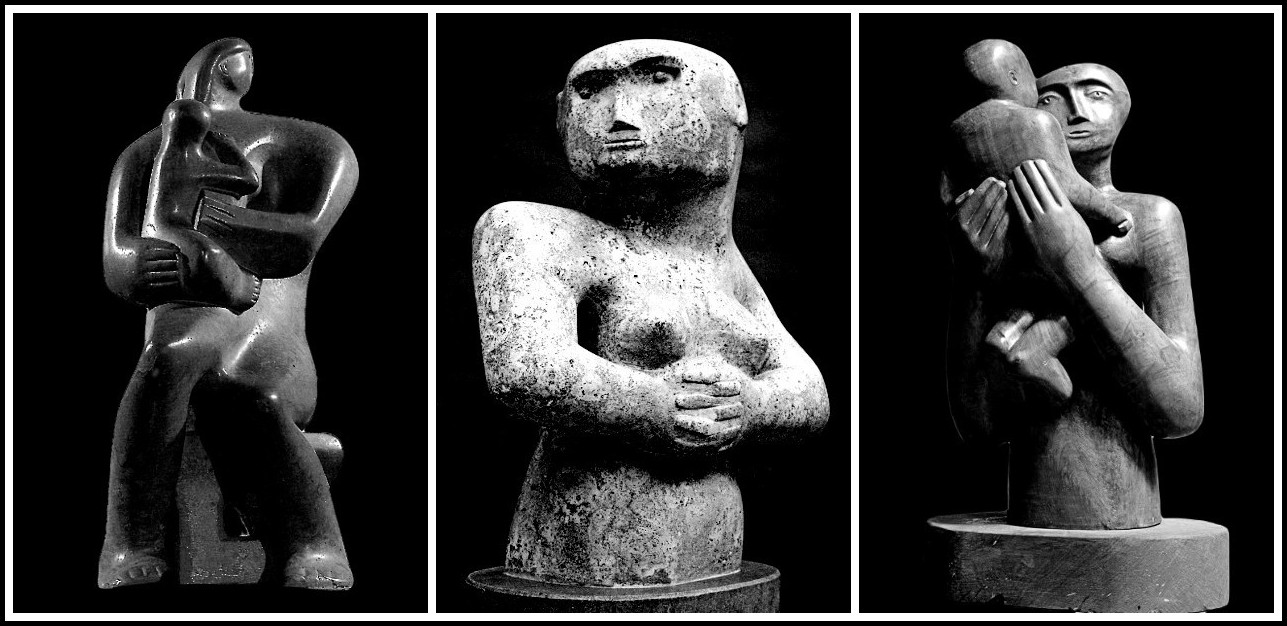

HENRY MOORE: Mother & Child, 1932 | Figure with Clasped Hands, 1929 | Mother & Child, 1931

Just because throughout my sculpture I’ve been interested in the same subjects—mother and child, reclining figures, seated figures—doesn’t mean I was obsessed with these themes. It just means I haven’t exhausted them and, if I were to live another hundred years, I would still find satisfaction in these subjects. I could never get tired of them, I can always discover new thoughts and ideas based on the human figure, it is inexhaustible.

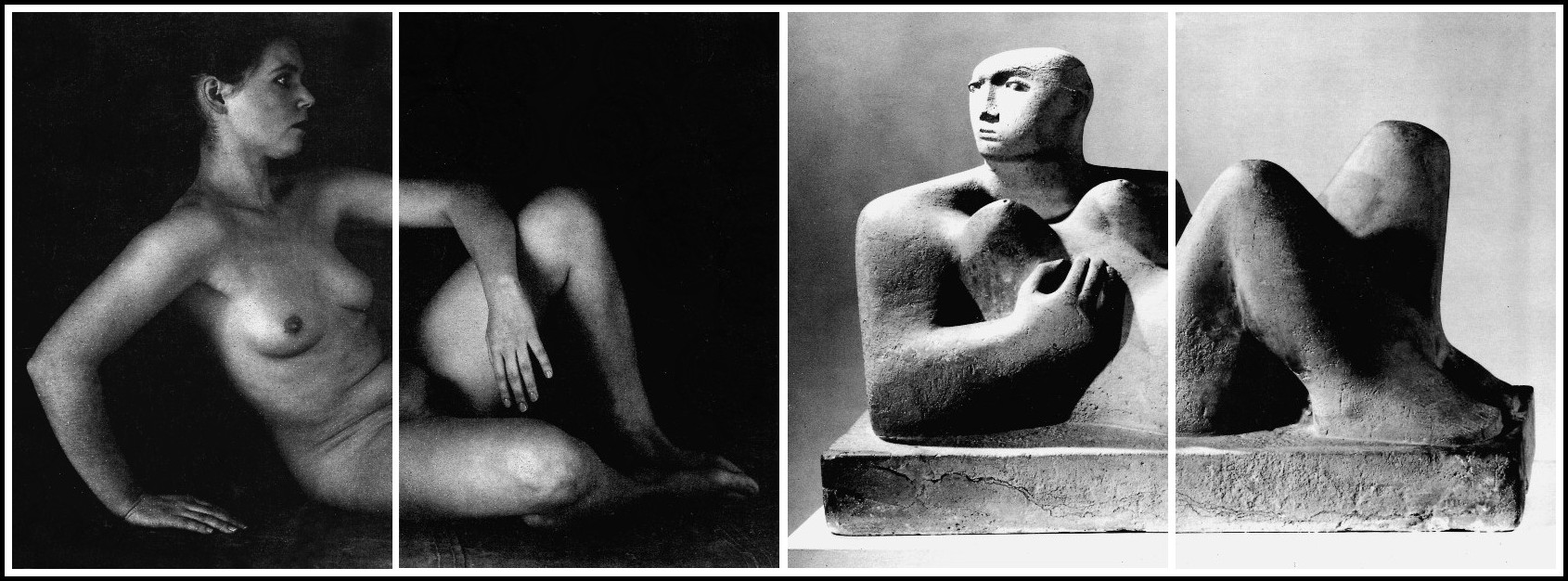

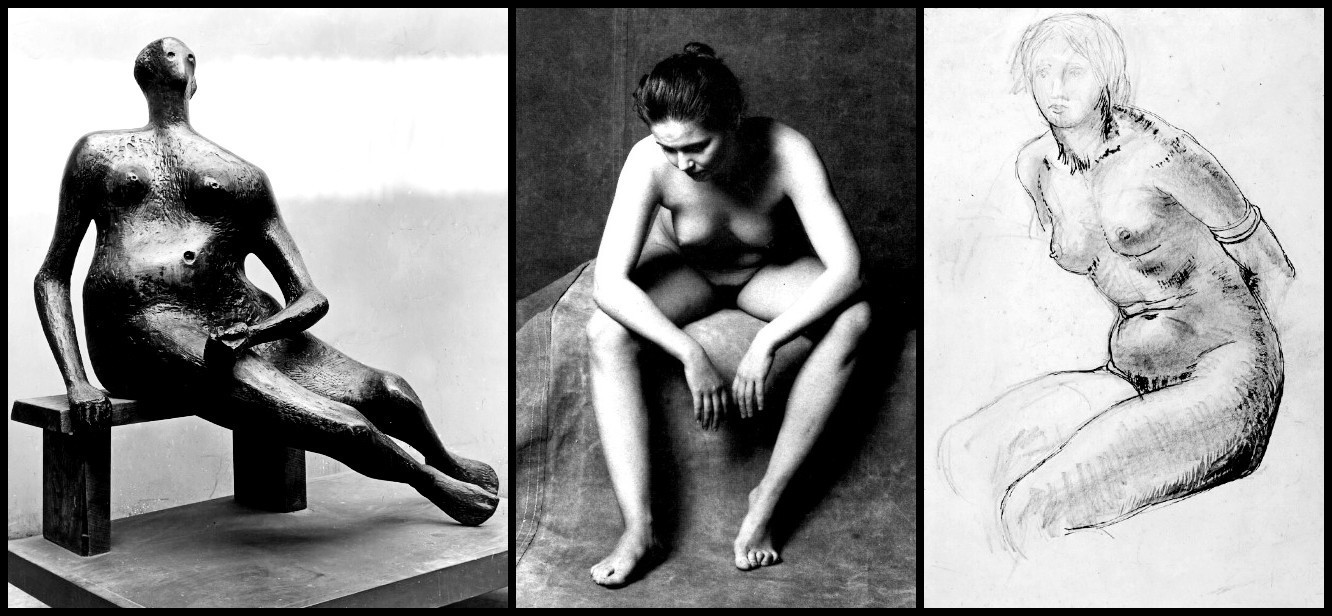

Henry Moore, Seated Woman, 1957 | John Hedgecoe, Female Nude | Henry Moore, Seated Woman, 1921

The whole of my development as a sculptor is an attempt to understand and realize more completely what form and shape are about, and to react to form in life, in the human figure, and in past sculpture. This is something that can’t be learnt in a day, for sculpture is a never-ending discovery. When Michelangelo said that sculpture could express everything, he did not mean that sculpture could replace the functions of all the other arts, or that sculpture could play a banjo! He meant that it can express so much that you don’t need to worry about what it can’t do. In that sense it was enough for him. It is enough for twenty lifetimes.

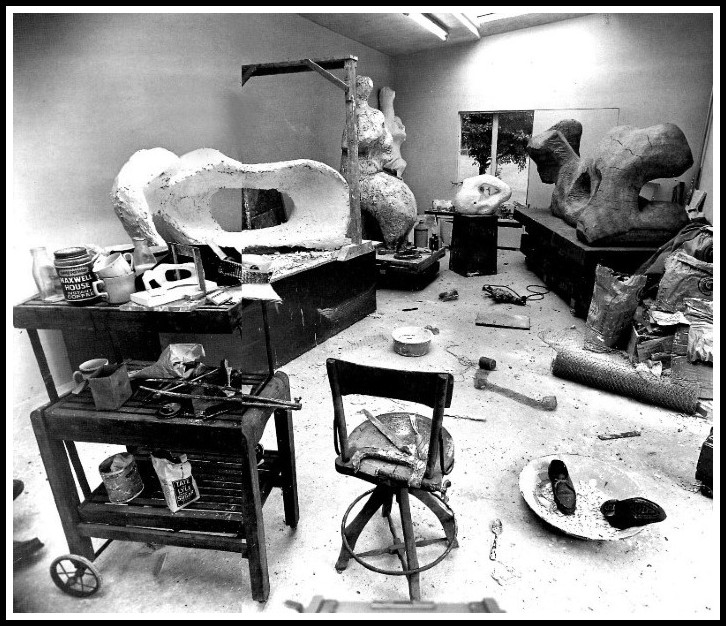

John Hedgecoe, Studio, Henry Moore

I cannot draw while I’m looking. I just let my eyes take in what is in front of them. I store it all up in my memory; this has always been so. I then will draw for several days, not copying, but creating from my imagination, perhaps relating to many experiences in the one drawing. I will then attempt to bring a three-dimensional solidity, showing the shape of an object by means of light and shade. I might use sketches, notes I made at the time, or even photographs, but most of it comes from my remembered experience of what I have seen and felt. An artist’s raw material is what he has seen and done so I still have to refresh my eyes every day. It is not enough to sit in my comfortable chair surrounded by outstanding examples of fine art. I have to go out every day for a drive, to see nature, the countryside, the trees, the sky, to be renewed and refreshed. The drawings I make reflect my love of nature. Even now, at the age of 87, it is necessary to go out for a drive each afternoon because it refreshes my vision. An artist lives through his eyes, as a musician lives through his ears. One can’t go on living on the same material. One’s memory is one thing, and very valuable it is too, but it has to be refreshed. I enjoy my afternoon drives enormously, I see different things, even if I go the same route, because the light is always different.

John Hedgecoe | Henry Moore

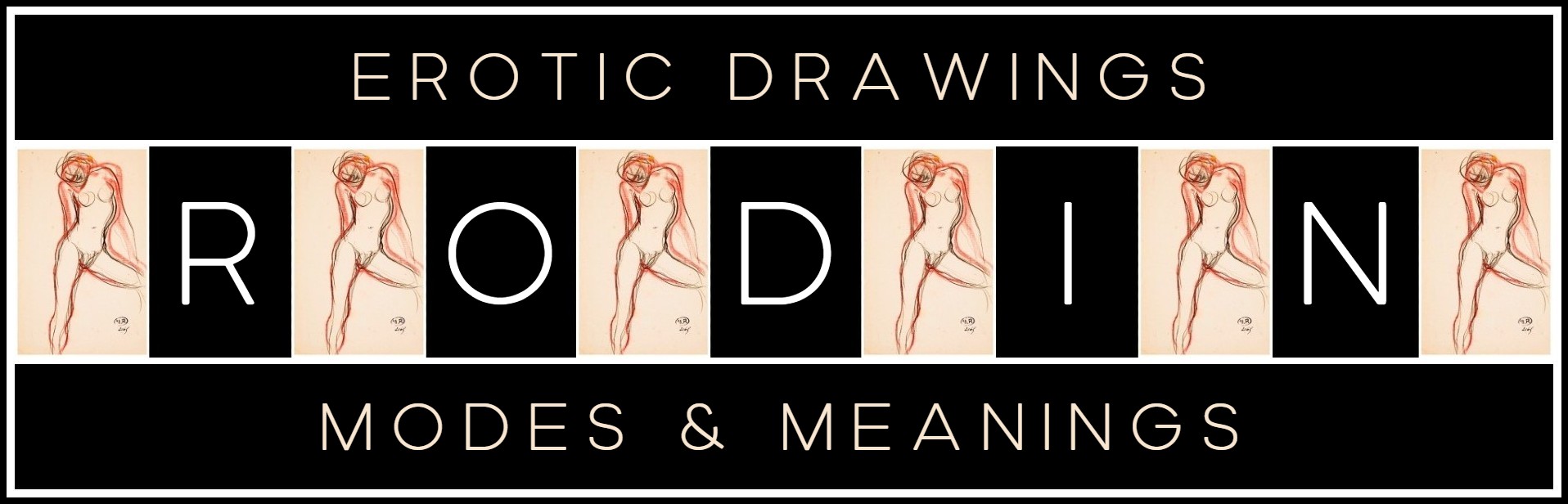

II. HENRY MOORE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel, ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 3

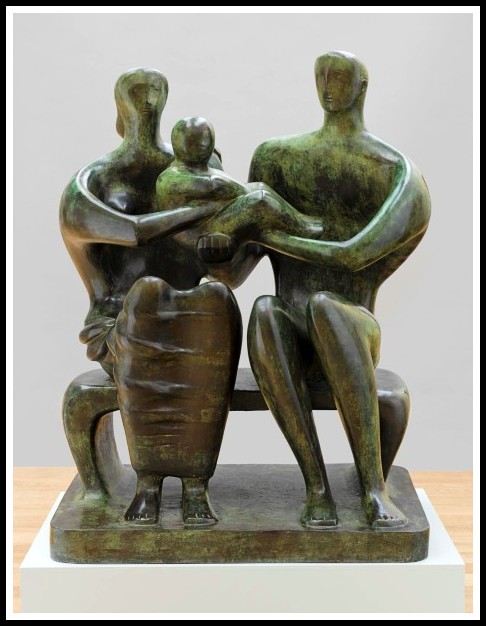

And then your mother led you to the Henry Moores: Reclining Mother and Child (1961), Family Group (1949), and another Mother and Child (1931).

̶ ‘Henry Moore was obsessed with the theme of mother and child’, you read aloud.

Nika is embarrassed, saddened, she wants to walk away: She stands firm and holds her ground because you are strong enough to stay.

̶ Why? you ask your mother.

̶ Because, from a compositional point of view, it’s a very rich subject.

Henry Moore, Family Group, 1949

̶ Did he have a lot of children?

̶ Just one. A daughter, Mary.

̶ Like us! says Nika, aiming her complicit eyes at you.

̶ Yes, like us!

Nika throws her arms around you; your laughter harmonizes with hers.

Henry Moore, Mother and Child, 1931

While Catherine speaks of the relationship between small and large forms, of position and balance, domination and tension, all you feel is emotion. As you circle the sculptures, something in you is stirred—despite your pride in your independence—by the tenderness in these depictions.

̶ Which one do you like best? Nika asks.

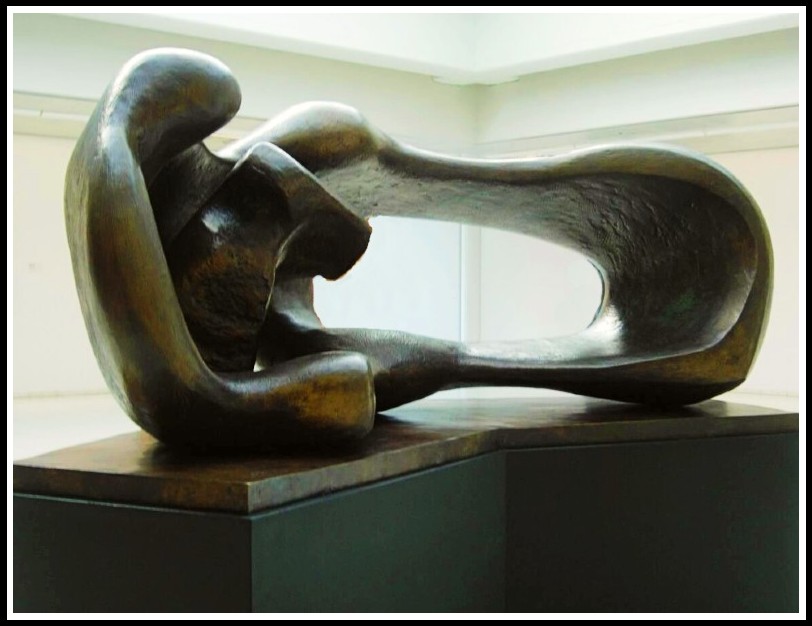

̶ This one, you say, pointing to the Reclining Mother and Child.

̶ Why? your mother asks.

̶ Because of the big hole in it.

That evening, after supper, Zoran taught you some card tricks. You mastered them, but it only made you miss your father more. You said goodnight early to everybody, and as soon as you were in bed you fell into a sleep in which you soared in space like Brancusi’s birds and walked through the streets of New York, hand-in-hand with Nika and Henry Moore.

Henry Moore, Reclining Mother and Child, 1961

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

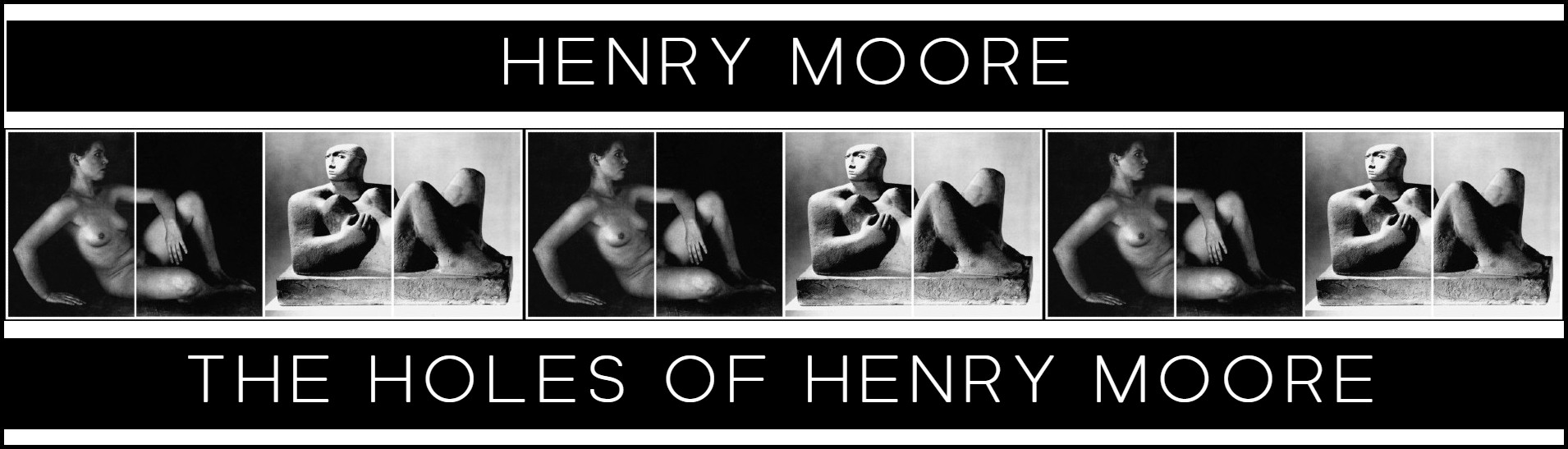

III. THE HOLES OF HENRY MOORE: ON THE FUNCTION OF SPACE IN SCULPTURE

Rudolf Arnheim

The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 7, No. 1 (September 1948)

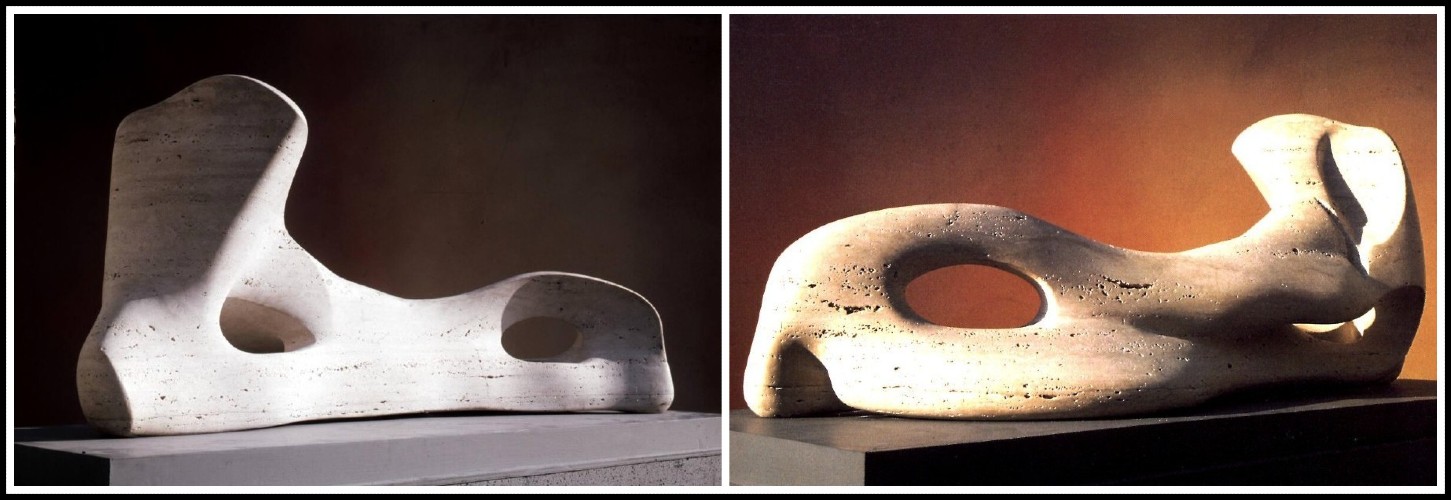

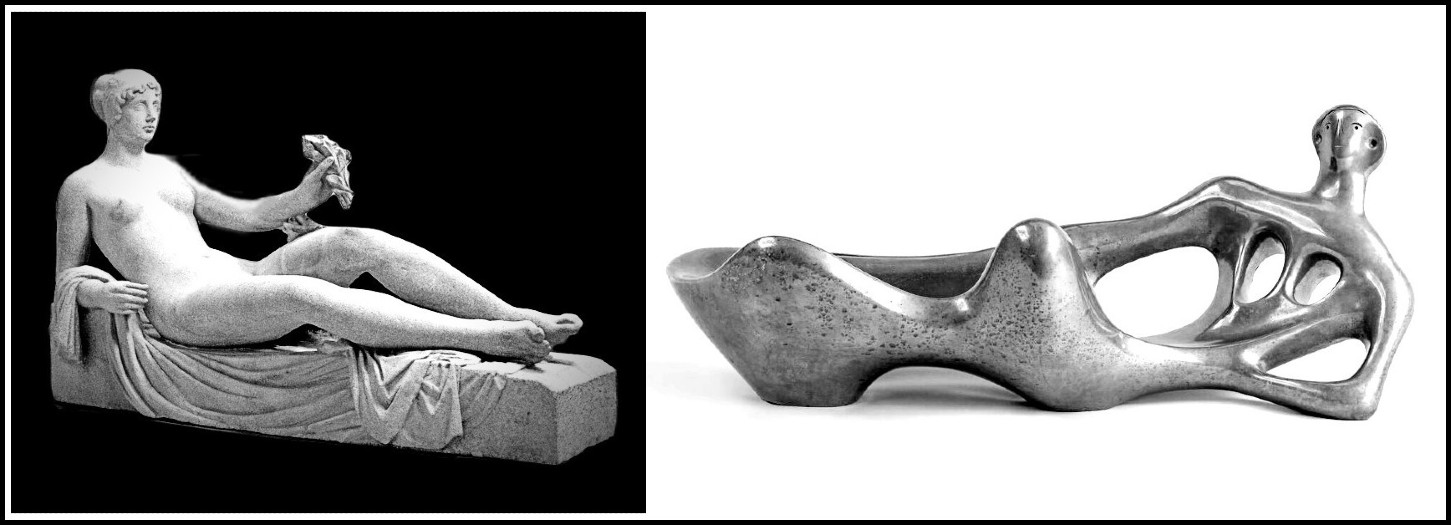

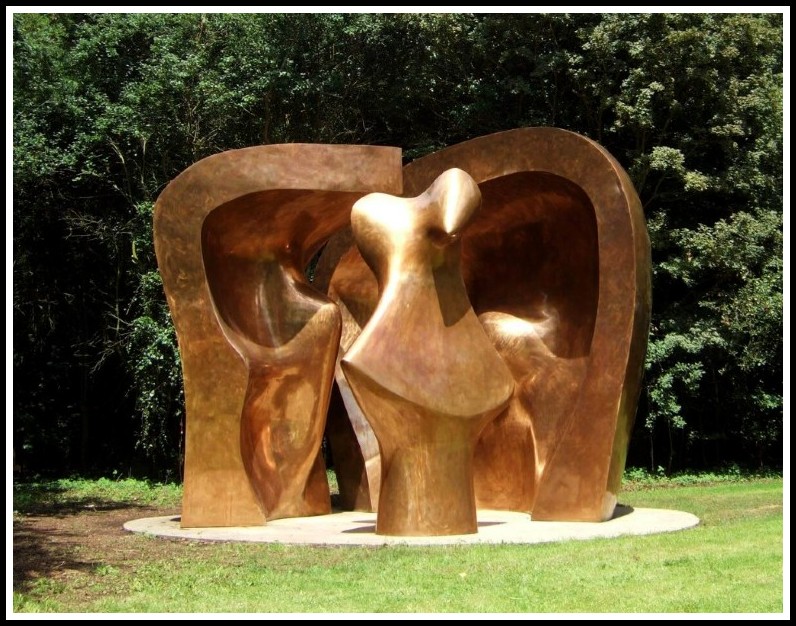

In the works of Henry Moore’s recent style, the trunk of the figure is often pierced and subdivided in such a way that instead of a compact volume one sees a configuration of slimmer units. For instance, the chest may be given as a large hole, which is roofed by the shoulders and flanked by the upper arms. What is the artistic purpose of this peculiar procedure? The human figure has always presented the sculptor with a compositional problem. The body consists of a heavy trunk and the much slighter appendices of the arms, the legs, and the head. Since the artist’s task is not to copy what he sees but to create a whole pattern of unified form, he must find a way of imposing unity on so heterogeneous an object. How can he organize the trunk and the limbs in one integrated composition?

Henry Moore, Reclining Figure: Bone, 1975

A valuable monograph could be written on the various ways in which different styles of sculpture have coped with the problem. Some fused trunk and limbs into one volume. Others reduced the trunk to stick-like slimness, thus assimilating it to the limbs. Again, limbs could be made short and plump to match the trunk. Intermediate volumes also can be introduced to bridge over the difference between the bulky and the slim. When the artists came to handle the human body more freely they sometimes eliminated the problem by cutting off the limbs and the head. Henry Moore’s solution is of a similarly radical nature. By transforming the heaviest volume, the trunk, into a configuration of narrower shapes, a common denominator has been found for the whole figure. The beam-like or ribbon-shaped units which represent arms and legs differ little from those which are found in the area of the trunk; and the holes that pierce the body resemble those between the legs or between the arms and the torso. In some of the reclining figures, a surprising symmetry is produced by the correspondence between the frame of the pierced chest and a similar frame formed by the two legs. Ingeniously balanced, the figure reposes on its horizontal base.

Henry Moore, Reclining Figure, 1959-64

Uniformity of the parts is one method among others to accomplish unity. Without ever getting repetitious, Moore stresses uniformity, not only in the roughly equal size and proportion of the units, but also in their shape. More and more has he come to eliminate the distinctive formation and detail of faces, hands, feet in favor of some over-all shape characteristics. Wherever we look we notice strongly dynamic form: the tranquillity of the cylinder, cube, or sphere is avoided in favor of conic or pyramidal shapes, which grow smaller or bigger, and egg-shapes, which drive in a definite direction. Moore enhances uniformity and vigorous mobility also by avoiding clear delimitation of parts. Even though precisely articulated, the units flow into each other. Even the dead-ends of the hands and feet are eliminated. They merge with each other or stream back into the body of the figure, thus permitting the circulation of energy to continue unchecked.

Henry Moore, Reclining Figure: Holes, 1976-78

This stress of the interdependence of things, their mutual influence, the indivisible unity of the whole is likely to reflect the artist’s conception of the world. But the structural pattern which conveys this meaning is possible only at a high level of formal development. True, no work of art lacks an intimate interdependence of parts, but it is well known that at early levels of conception, for instance in the drawings of young children, the complex patterns of a human figure or an animal are built of geometrically simple units, which are kept apart through explicit outlines. Gradually, these subdivisions disappear and the whole is conceived as one complex unit. Only at a late state of this process of growth, which has a parallel in the developmental laws of human thinking, can the complexity of dynamic interchange be grasped through scientific or artistic patterns. One can express this also by saying that stylistic structures like the one created by Henry Moore approach the representation of the irrational. This is a romantic tendency, which shies away from the defined and congealed. Moore’s romanticism cherishes the mysterious intangibility of what grows, changes, and interacts. Herbert Read has aptly analyzed his romantic attempt to derive an image of man from the organic and inorganic formations of nature.

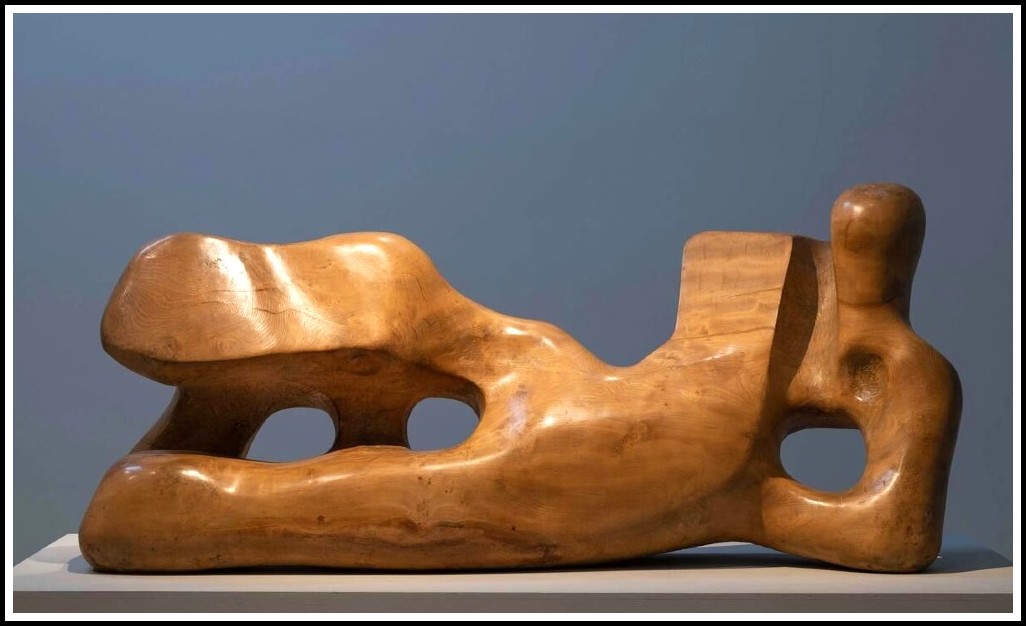

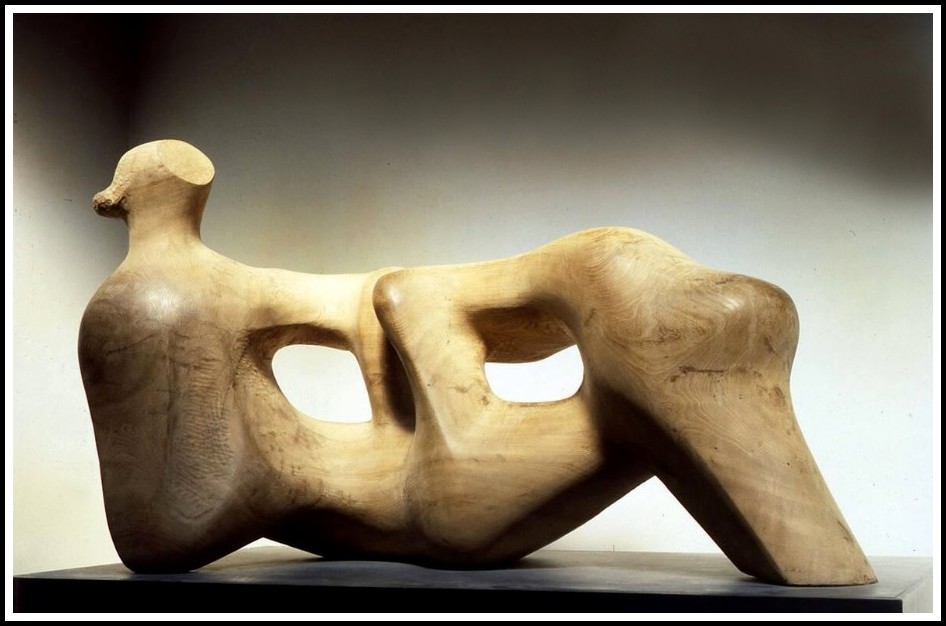

Henry Moore, Mother and Child, 1978

The equalization of the parts, obtained by the breaking-up of the trunk, tends to minimize the biological difference between the limbs as executors of voluntary action and the trunk, which is more directly connected with the vegetative, instinctive functions. A uniform overall-principle of life seems to govern the whole figure in all its parts. This playing down of the late cerebral developments of homo sapiens in favor of more universal forces of nature is again a romantic trait of Henry Moore’s art. One notes in this connection that the horizontal position, which he uses so frequently, devaluates the importance of the head and stresses the abdomen as the compositional center. The heads are small. That is, the role of the brain carrier is reduced. These faceless heads do no thinking or feeling of their own; at most, they occasionally turn around to gaze with the simple steadiness of grazing cattle. Similarly, the tentacles of the hands and feet are planed down, fused, tied together. One has only to think of the alert faces and telling gestures of the terracotta figures which rest on Etruscan coffins in almost the same position to realize the difference. The grace and intelligence of Moore’s work is all in the form pattern which characterizes the whole figure with no distinction of any specific part.

Henry Moore, Reclining Figure, 1939

Another glance at the holes leads us to notice that they are not merely dead and empty intervals between the material parts of the figure but peculiarly substantial, as though they were filled with denser air. Among the factors that make for this effect, one stands out in particular. The surfaces which delimit the openings are frequently not convex but are concave, forming hollow containers of space. Striking examples are the spherical holes which pierce the chests of some of the female figures to indicate the breasts; or the circular holes in ring-shaped heads; or the dells formed by bent arms. Wherever such concavities dent or perforate the sculptural body, a puddle of air seems to fill them almost tangibly.

Henry Moore, Working Model for UNESCO Reclining Figure, 1957

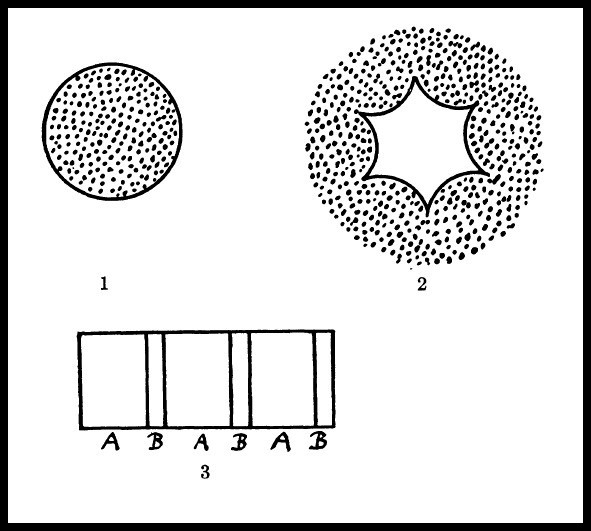

In observing this phenomenon the psychologist cannot help thinking of the studies on ‘figure and ground’ started by Edgar Rubin1. A pattern like the one in Fig. 1 is seen by most observers as a circular disk (‘figure’) in front of a through-going background (‘ground’). It is harder to see a white foreground (‘figure’) pierced by a circular hole, through which part of a dotted background (‘ground’) appears. Psychological research has discovered some of the conditions on which the figure-and-ground effect depends:

1. The enclosed surface tends to be figure, the enclosing, ground.

2. Inner articulation, such as the dotted texture of the circle, makes for ‘figure’. An empty circle would show the effect less clearly.

3. Convexity makes for figure, concavity for ground.

In Fig. 2, the second and third factors are reversed. This time, the internal pattern, in spite of being enclosed, tends to be seen as a hole because it has less texture and a pronouncedly concave contour.

1 – Updated reference: Jörgen L. Pind, Edgar Rubin and Psychology in Denmark: Figure and Ground (London: Springer Nature, 2015)

Figures 1 – 3

In any drawing or painting, figure-ground relationships help create the pictorial space. This is true not only where human bodies, houses, etc. are shown in front of a background, but wherever objects or parts of objects overlap. Generally, a number of figure-ground factors are used simultaneously and for the most part antagonistically. That is, a tree may be made to appear in front of a wall, as figure on ground, while at the same time other factors will check the effect by stressing the figure-character of the wall. The reason for this is that the painter has always to cope with the double task of creating space and ‘keeping the plane.’ Even where a human figure is shown in front of a homogeneous background, as in the portraits of Holbein or the Quattrocentisti, the unity of the picture-plane can be preserved, for instance, by the amount of space and the color and brightness given to the background.

Holbein the Elder, Portrait of a Woman, 1519 | Ghirlandaio, Portrait of a Young Woman, 1490

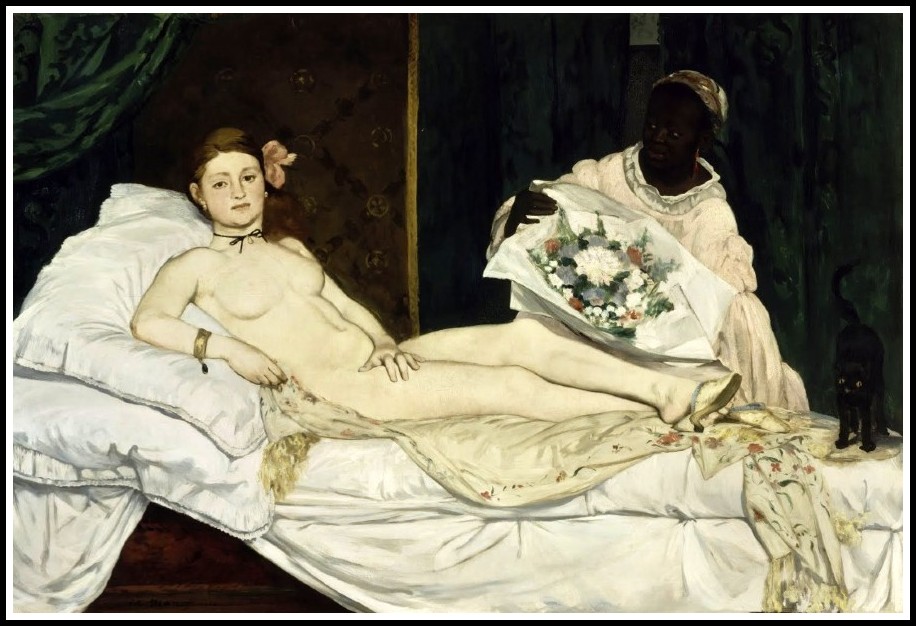

Thus far, psychologists have studied the phenomenon of figure and ground only in plane patterns, but their results can be applied to the third dimension. True, there are important differences. Whereas in a two-dimensional drawing the contour which divides two areas can be observed, the common boundary surface remains hidden when two opaque volumes meet in three dimensional space. You can see the line which separates Olympia’s body from the divan on which it rests, but not the surface which the body and the divan share three-dimensionally. An exception occurs when one of the two volumes is transparent, as in the case of air enveloping an object. In this case, however, the transparent volume is non-existent for our eyes to such an extent that one hesitates to speak of a figure-ground relationship at all. It seems more proper to say that a piece of sculpture is surrounded by empty space than that it is seen on a positive ‘ground.’

Manet, Olympia, 1863

Within the frame of a painting every spot is positively present, first as a material part of the paint-covered canvas and secondly as a substantial element of the pictorial construction. In a completed painting, the units of the composition vary as to their apparent density and also as to their spatial position within the figure-ground hierarchy, hut none of them may give us the impression of an empty gap, a hole torn in the pictorial tissue. This is different in sculpture, where we are used to find all spatial relationships limited to the figure itself. These relations often reach across a void and the length of the leap counts compositionally but they generally do not include these intervals the way they would in a painting. It seems necessary to state this principle of sculpture so positively even though it does not hold completely. The deviation from it which can be observed in Henry Moore’s work has historical antecedents. For our purpose it suffices to point out the changed attitude to space in the most extreme but at the same time artistically valid example that is available so far.

Henry Moore, Two-Piece Reclining Figure: Holes, 1975

Mainly through the use of concave forms, many a figure of Henry Moore’s captures portions of space and makes them a part of itself. Much less solid than the wood, stone, or metal with which they unite, these air-bodies nevertheless condense into a transparent substance, which mediates between the tangible material of the statue and the surrounding empty space. Psychologically speaking, these statues do not reserve all the ‘figure’-factors for themselves. They do have all the ‘inner articulation’ and are enclosed by the surrounding volume of air. But on the other hand they do not consist entirely of bulging convexities, which would invade space aggressively, but reserve an important role to dells and caves and pocket-shaped holes. Whenever convexity is handed over to space, partial ‘figure’-character is assumed by the enclosed air-bodies, which consequently appear semi-substantial. Family Group (1945) shows a man and a woman sitting next to each other and holding an infant. In most traditional works of sculpture the space enclosed by the seated body is essentially delimited by bulging convexities of the chest, the belly, the thighs. Thus it remains an empty interval. In Moore’s family group, hollow abdomens make the two seated figures into one large lap or pocket. In this shadowed cavity, space appears tangible, stagnant, warmed by body heat. In its center, the suspended infant lies safely as though contained in a womb softly padded with half-solid air.

Henry Moore, Family Group, 1945

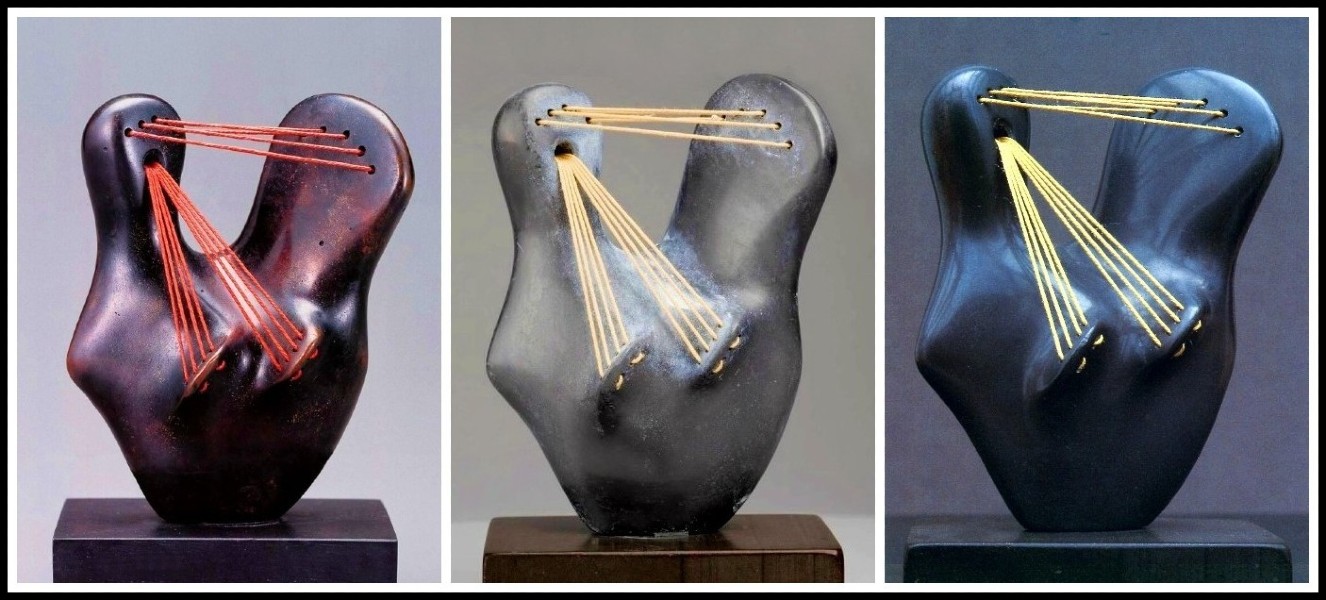

Since the holes are often shaped according to the same principle, it will he seen that they pierce the body of the statue in a material but not necessarily in a perceptual and artistic sense. In many cases they do not interrupt the substance of the figure but merely seem to rarify it into a state of transparency. This new function of space offers compositional opportunities. Sometimes, Moore establishes a contrapuntal correspondence between, say, a protruding head and a hollow of similar spherical shape. These instances prove that almost equal rights are conceded to hollows and solids. Incidentally, this interpretation also seems to throw light on another disturbing feature of Moore’s style, namely his use of strings and wires. The strings form surfaces which bound transparent bodies consisting of empty space. They too add volumes of rarified substance to the more solid principal material of the statue. At the same time, the directions of the strings interpret the shape of the volumes they enclose very much like the lines of the grain which Moore uses so deliberately in his wooden and stone figures. Curiously enough he thus applies the theoretical recipe of another English artist, William Hogarth, who in his ‘Analysis of Beauty’ recommended the interpretation of volumes through similar systems of lines.

Henry Moore, Mother and Child, 1938

The essentially negative role which the surrounding air-space has played in sculpture so far is not due simply to its invisibility, but also to the predominance of convex volumes in the figures themselves. Henri Focillon, in his stimulating book, Vie des Formes, has distinguished two ways of using space in sculpture, namely l’espace-limite and l’espace-milieu.

Espace-limite: space more or less weighs upon form and rigorously confines its expansion, at the same time that form presses against space as the palm of the hand does upon a table or against a sheet of glass.

Espace-milieu: space yields freely to the expansion of volumes, which it does not already contain: these move out into space, and there spread forth even as do the forms of life.

It seems to me that in the interpretation of l’espace-limite, too active a part is granted to the surrounding space. An archaic Greek figure, for instance, does not give me the impression that an inner urge to expand is checked from the outside. The discipline of such a style is all ‘internal.’ It is dictated by the law of development which limits formal complexity at the early stages. There is little capacity or desire to expand beyond the basic block. The function of the surrounding space is almost exclusively negative. The same holds true for l’espace-milieu. From the center of the figure bulging volumes push forward into empty space.

Espace-limite/Espace-milieu: An interpretation

Once this principle is stated, a more detailed analysis will trace here at the same time admixtures of a third procedure, which one might term l’espace-partner. In later Greek, medieval, and particularly baroque sculpture the use of concavities indicates the possibility of making space an active partner of the figure. In Bernini’s horseback-riding Louis XIV the sweeping locks and folds collect the air in hollow pockets. But even here the concavities are subordinated to the convexity of the whole to such an extent that they contribute no more than a minor enrichment. Among the great sculptors, Henry Moore is the first in whose work the surrounding space is not simply pushed out of the way by the aggressive protrusions of the wood, stone, or metal, but in turn thrusts into the figure from the outside, carving depressions into the yielding matter and adding to its substance. The proper balance and integration of the two antagonistic tendencies is a delicate task for the sculptor, in that the totality of the internal and external pushes must create one consistent unified surface. There are instances in Henry Moore’s work where space, as if with a ramming thumb, interrupts the rhythm of the figure with a foreign imprint.

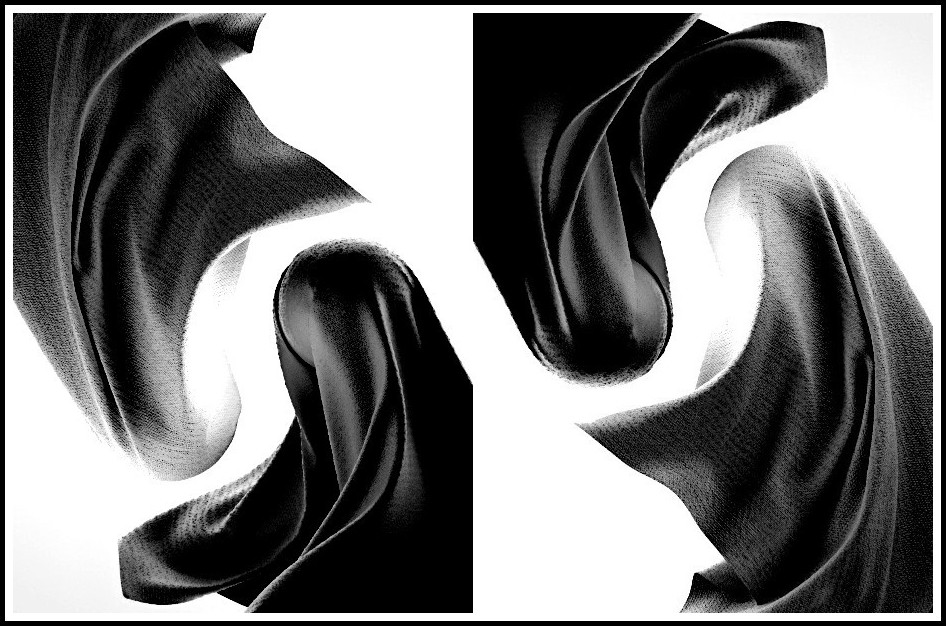

Henry Moore, Composition, 1931

The foregoing examples will have shown that the figure-ground relationship is not simply a static distribution of spatial values but a highly dynamic interplay of forces. This is even true for two dimensional patterns. The ‘figure’ is distinguished not only by appearing in front of the ground and by its greater density but also by a tendency to expand, to spread over the territory of the ground. In Henry Moore’s sculpture the two-way relationship in which both the statue and the surrounding space assume figure as well as ground functions makes for a dramatic interchange of forces between the two partners. The sculptural body ceases to be a self-contained, neatly circumscribed universe. Its boundary has become permeable. It has been inserted into a larger context. The masculine activity of its pushing convexities no longer operates in the void but is countered by positive thrusts from the outside, which force the additional role of feminine passivity on the sculpture. In other words, the tendency to avoid isolation and delimitation, to unite parts in an exchange of forces rules not only within the figure but is applied also to the relation of figure and environment. This is a daring extension of the sculptural universe, made possible perhaps by an era in which flying has taught us through vivid kinesthetic experience that air is a material substance like earth or wood or stone, a medium which not only carries heavy bodies but pushes them hard and can be bumped into like a rock.

In Maillol’s Monument to Cézanne (1912), the restfulness of the position is contrasted with active convex volumes.

Moore, in his Reclining Figure (1945), expresses passivity by concave form.

How valid is this sculptural style artistically? How far can it lead and where? Undoubtedly it involves problems. Since we are all accustomed to thinking that definite boundaries are needed to determine the structure of a work of art, we notice with apprehension that the inclusion of space removes clearly defined delimitation. Those puddles of condensed air which fill holes and depressions have definite contours only where they border upon the body of the figure. For the rest, they seem to dissolve into empty space, thus leaving the work peculiarly open. True, the cubist painters, such as Feininger, have dispensed substantial air in crystalline form, but they had the picture-frame to keep all volumes within the bounds of a rectangle. Henry Moore’s figures are frequently enveloped by a field of energetic matter, which weakens in power and density with increasing distance from the figure and finally evaporates. Incidentally, a similar infinity, in the opposite direction, is provided by deep hollows, whose internal end is hidden in the dark. The artistic implications of this style will need to be explored further.

Henry Moore, Three-Way Ring, 1966

Where will the principle of concavity lead? Its complete realization is known to us only from architectural interiors. But is there any aesthetic law to prevent the sculptor from creating hollow interiors, works one would have to walk into in order to see? I hesitate to call up the experience of climbing the staircase inside the Statue of Liberty. Even so, the principle deserves a trial. The two settings which have attracted Henry Moore as a draftsman are the hollow tube shelters and the interior of coal mines. His ‘Helmet’ would offer to a mouse-sized visitor the most radical experience so far available of the use of surrounding concavity in sculpture.

Henry Moore, Helmet Head No 1, 1950

What prospects are opened by Moore’s attempt to decompose large volumes into configurations of slimmer units freely separated by interstices? Undoubtedly, such a style offers to the spectator a more complete survey of spatial relations. No more than three side-faces of a solid cube can ever be seen from one viewpoint. Looking at an open box, we visualize all six of its planes, some from the inside, some from the outside. The skeleton of a cube built of twelve sticks offers even more complete orientation. This principle applies also to the more complex bodies of sculpture. On the other hand, decomposition of volumes carries a greater risk of disintegration. I notice a lack of unity in some of Moore’s smaller metal compositions. The reclining figures of the deck-chair type are not easily pulled together by the glance. This, however, is merely a matter of artistic accomplishment. There is no reason why even Moore’s radical attempt to compose a figure of several entirely separate pieces could not be successful. Perceptual unity does not require physical continuity. Extended beyond the single figure, this principle leads to group compositions, which are indeed a major interest of Moore’s.

Henry Moore, Three-Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No 2: Polished, 1962

It can readily be seen that this sculptor, by his positive use of intervening space, might be more successful in the combination of separate units than Western sculpture has been traditionally. This may also lead to an extension of subject matter. So far, sculpture has fed almost exclusively on the compact bodies of humans and animals. Some playful experiments in modern sculpture, for instance those by Calder, make me wonder whether some day a group of twisted tree-trunks, which would delimit and internally organize a volume of essentially empty space, could not become a legitimate subject. Finally, a more dramatic interrelationship of sculpture and architecture could be envisaged, in which the building would be more than an enclosing box, the statue more than an enrichment of walls. Architectural and sculptural forms could unite in the kind of dynamic interplay which we observe in Henry Moore’s arrangements of separate non-objective shapes. Further than this the speculation cannot go, since the theorist of art must not trespass upon the land of the prophet. His is a science which allows little prediction. While it seems possible to foresee some of the main directions in which social, scientific, and technical development will move, the road of the arts cannot be traced beyond the next corner.

Henry Moore, Large Figure in a Shelter, 1985-86