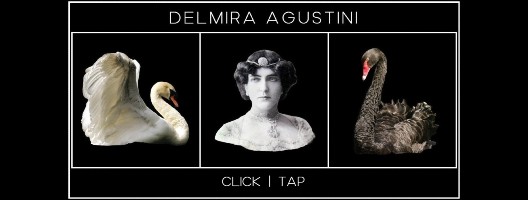

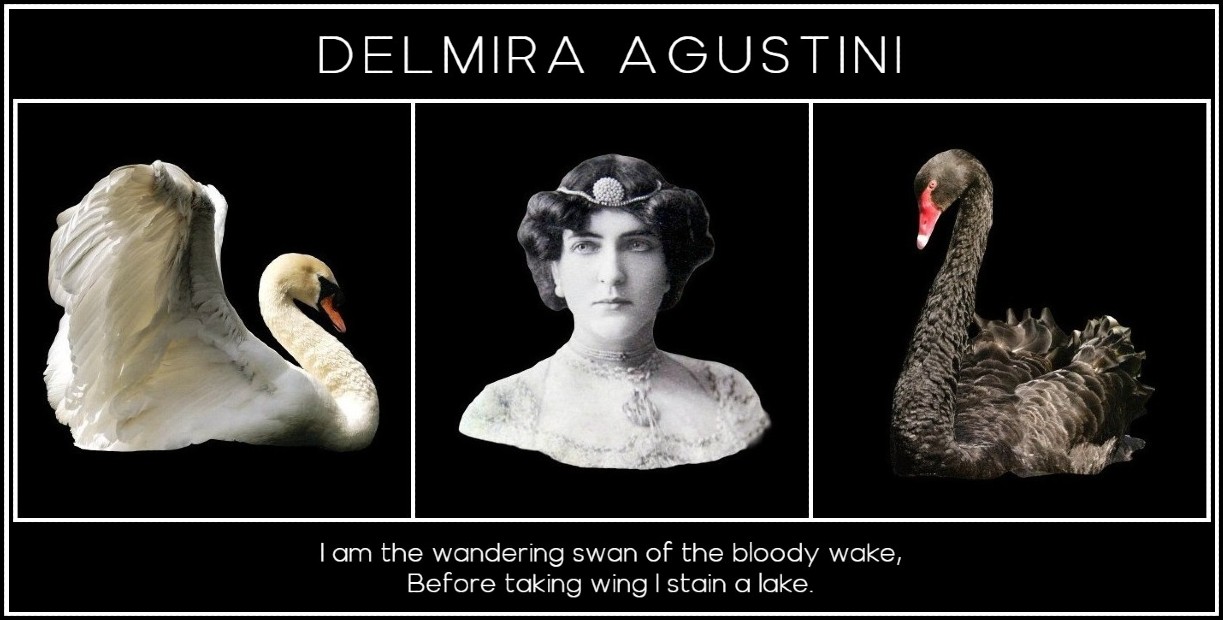

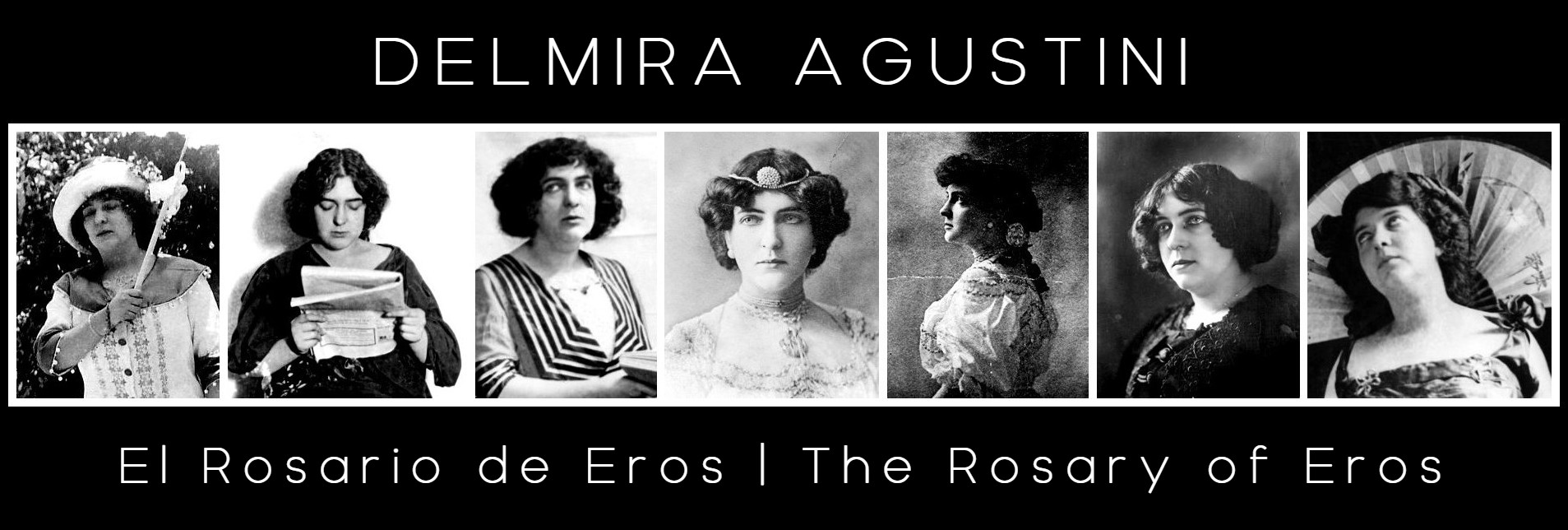

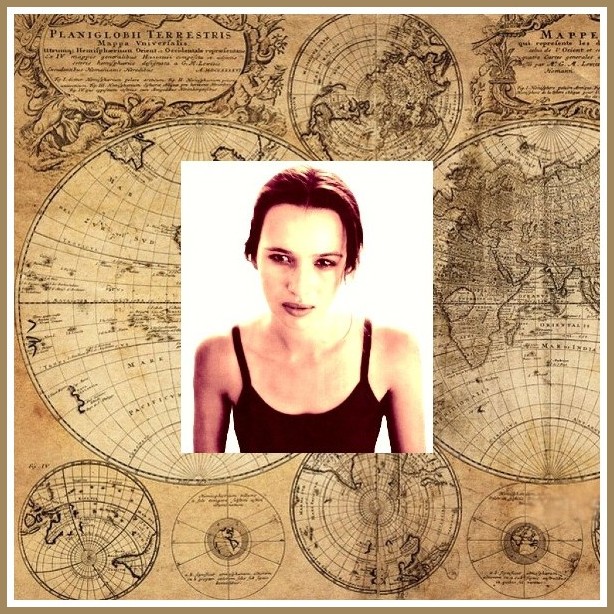

Delmira Agustini

Tarjetas postales (Post cards) | Delmira Agustini Archive | Images courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de Uruguay | Composition by RJ

PART I

TWO READINGS OF THE SWAN: RUBÉN DARÍO & DELMIRA AGUSTINI

Sylvia Molloy

Translated from the Spanish by Richard Jonathan

This essay, now a classic, was first published in La sartén por el mango, Santo Domingo: Corripio, 1985, pp. 57-70. I have translated it here in its entirety (and given titles to the 3 sections).

A pdf of the original is available from Revista de la Universidad de México. At the end of the essay you will find a biographical note on Sylvia Molloy.

Jean-Jacques Feuchère, Leda and the Swan, 1845

I – DELMIRA AGUSTINI: CHARACTER & CONTEXT

Reading Delmira Agustini leads to the confirmation, always renewed, of her fundamental excess, of her fundamental rarity. Here I open a parenthesis: has Uruguay been sufficiently thought of as a privileged land of rare and truly original precursors? Think, beyond Lautréamont whose nationality can be disputed, of Herrera y Reissig, of Felisberto Hernández, and of Onetti, names to which must be added, for the rupture it marks, that of Delmira Agustini.

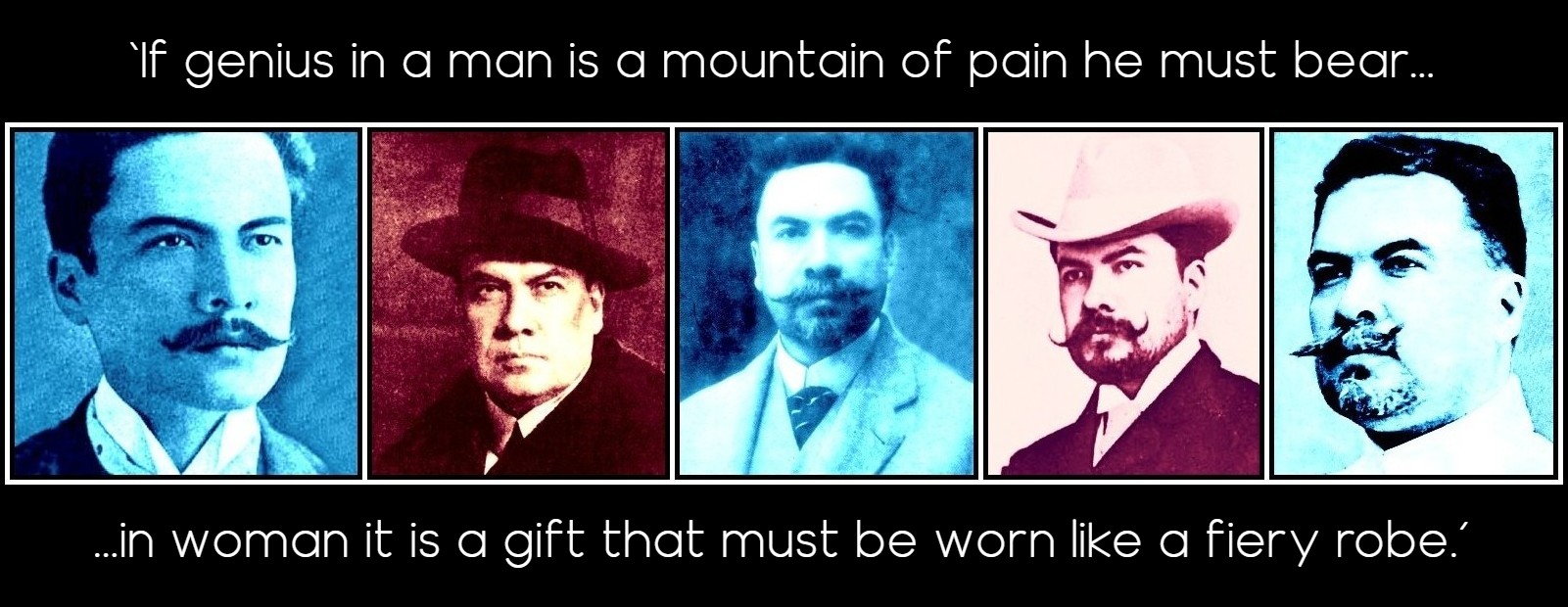

Juan Carlos Onetti | Lautréamont | Delmira Agustini | Julio Herrera Y Reissig | Felisberto Hernández

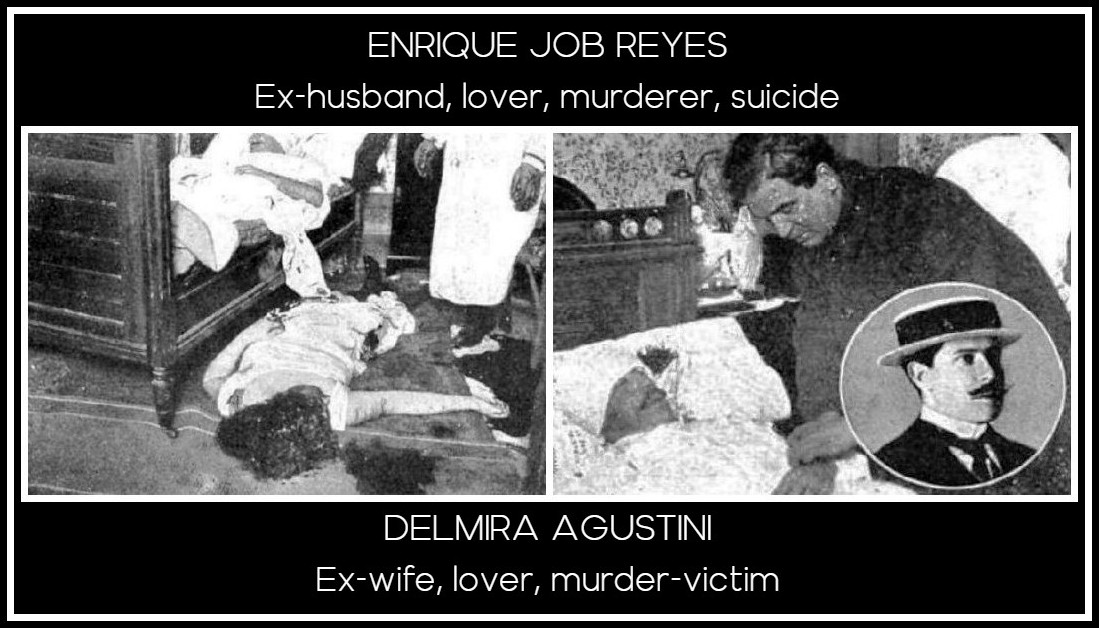

To show in what sense Delmira Agustini was a misfit, I will begin by briefly situating her in the period in which she lived. Born in 1886, at the age of sixteen she began to publish poetry in little magazines and to write a society column (under the splendidly cheesy pseudonym of Joujou) for a Montevideo periodical, La Alborada. In 1907 she released her first book of poems, El libro blanco (Frágil) [The White Book (Fragile)]. In 1910 her second collection, Cantos de la mañana (Morning Songs), was published, and finally in 1913 she released the third and last book published in her lifetime, Los cálices vacíos (The Empty Chalices), featuring a foreword by Rubén Darío. In it she announced an upcoming volume, Los astros del abismo (The Stars of the Abyss), which would be published posthumously under the title El rosario de Eros (The Rosary of Eros) in 1924. She died in 1914 at the age of twenty-eight.

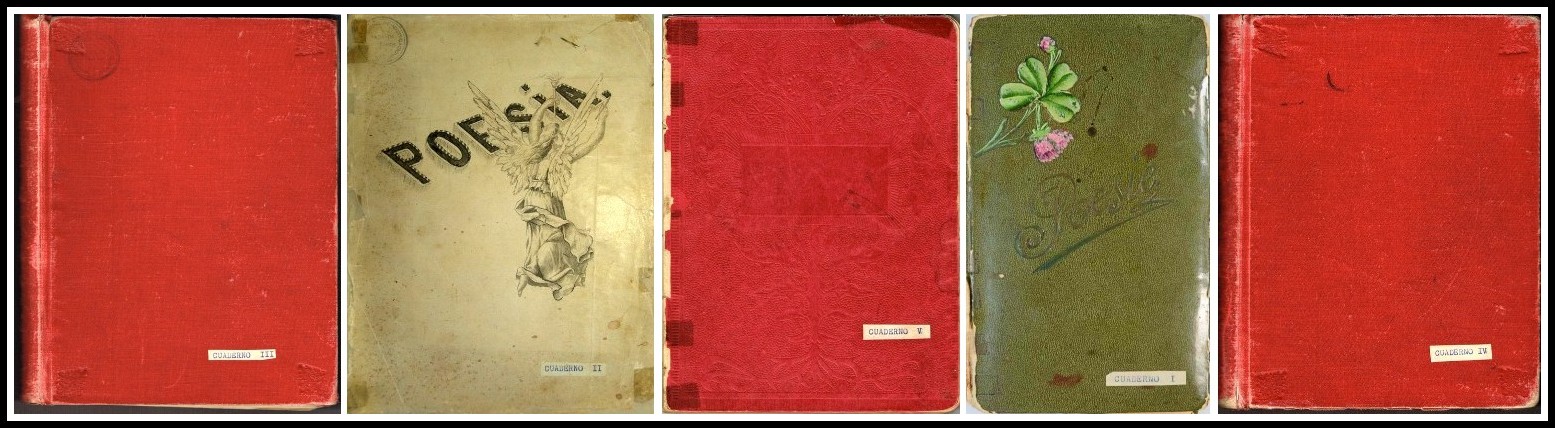

Delmira Agustini: Cuadernos (Notebooks) | Images courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de Uruguay | Composition by RJ

Emir Rodríguez Monegal has examined the systematic childishness to which Agustini was subjected ever since her first publications. In 1902, when he published her first poem, Samuel Blixen referred to her as a ‘twelve-year-old girl’ when in fact she was sixteen. The following year, in La Alborada, she was described as follows:

One fine morning she showed up at our editorial office, bringing us a work that she deposited with her little doll’s hands on the jumbled papers on our desk. She read it to us later in a delicate intonation, soft and crystalline. It was as if she feared breaking the gossamer of her song as she unwound it from her spinning wheel of brittle paper—delicate like her rosy body, frail like the lace of her verses.

From the same period we have this recollection from Raúl Montero Bustamante:

She smiled shyly while her father expounded on the child prodigy who was beginning to interest the men of letters of the time. She had nothing to add to the conversation, and after leaving the collection on the desk she left in silence.

Delmira Agustini: Tarjetas Pintadas (Painted Cards) | Images courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de Uruguay | Composition by RJ

Finally, Darío, in his foreword to Los calices vacíos (a foreword that is an all-too-typical invitation to misread the female poet) salutes Agustini—a twenty-seven-year-old woman at the time—as ‘this beautiful child’. Trotting out the threadbare cliché of the femme-enfant, this infantilization is remarkable in that it is adopted not only by those ‘men of letters’ Montero Bustamante mentioned—the paternalistic modernismo establishment—but also by Agustini herself, in the self-image she forges.

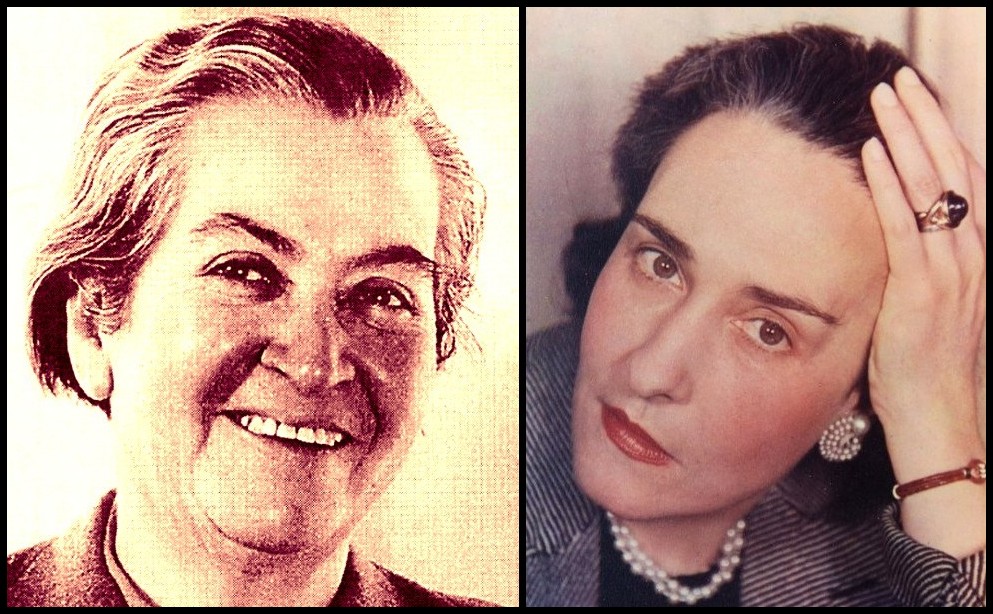

Ford Maddox Ford, Millie Smith, 1846

The care that certain writers devote to constructing their image, the energy they spend in fabricating and outfitting their persona, is a subject that merits serious attention. The matter is interesting not only for what it reveals about the writer—eternal Narcissus obsessed with his reflection—and the audience his image is aimed at, but also for what it reveals about the market forces at play in the writer-reader relation. The image is made up of both the writer and his persona. It consists in what the writer is, what he seeks to be, what it is in his interest to be and what he sacrifices for it. It can serve as both a revealing mirror and an opaque shield. These considerations, valid for every writer, deserve special attention when the writer is a woman. Indeed, the female writer’s professional image, being more fluid than that of her male counterparts, is less stereotyped. By not knowing what place she occupies—or thinks she occupies—in the world, she knows even less what place she occupies in literature. In addition to Agustini, by the way, two other writers whose image-building would repay further study are Gabriela Mistral, with her image of unconventional sexuality alongside matronly teacher and adoptive mother, and Victoria Ocampo, who, by devoting herself to disseminating the work of other writers, writers already recognized, shielded her own insecurities.

Gabriela Mistral | Victoria Ocampo (Photo: Gisèle Freund)

Delmira Agustini’s deliberate childishness—or better, ‘girlishness’, since she was called ‘La Nena’ (‘The Girl’) and used the appellation as her signature—is subject to diverse interpretations. While most of them are speculative, it is a fact that she was overprotected by her parents and that Mother’s prodigious presence weighed heavily on her. The photos we have of her bedroom, showing a doll enthroned in its center, are a sign of that self-willed infantilization, caricatural in character, that we find in certain Silvina Ocampo stories. The same childishness is found in her love letters to her boyfriend, Enrique Job Reyes, whom she sometimes called ‘Daddy’ or ‘my old man’. Occasionally, as in the following example, her baby talk gives the message a monstrous dimension:

My life! I want, I want… I want a little head of my Ricky [Enrique] that fits nicely in here [drawing of a heart]. I have been a very good girl. I say very, very good night, my dear old man. I’m always thinking of Ricky and I want the little, very little, head of my Ricky. See you! Have a nice afternoon, my dear old man. Your Nena

Think of this letter in relation to what surprised and attracted Unamuno when he read Agustini’s Cantos de la mañana: ‘That strange obsession that you have to hold in your hands, sometimes the dead head of the beloved, sometimes that of God’. Here infantilization, turning the head of the beloved into a toy, increases the strangeness of the obsession.

Uncanny dolls

The figure of ‘La Nena’, in its obvious deliberateness, is clearly a mask for Agustini. That, indeed, is how Rodríguez Monegal sees it: ‘‘La Nena’ was the mask the Pythoness wore in the world; it provided a solution to the family conflict she was caught up in, a conflict driven by a neurotic, domineering and possessive mother’. Arturo Sergio Visea, in his preface to Agustini’s correspondence, shares this interpretation. He understands her baby talk to be a code that, in the face of Mother’s prying eyes, veils the true nature of the relationship between Delmira and Enrique. However, beyond these purely private circumstances (which justify the ‘Nena’ mask), Agustini, in her public persona too, adopted this disguise. Why? Because it offered protection in a difficult situation and provided a solution, however provisional, to her dilemma. Let us now examine a particular instance when Delmira Agustini asserted her persona and used her mask: her relation with Rubén Darío.

Tarjetitas para publicidad de cigarrillos (cigarette advertising cards) | Delmira Agustini Archive | Images courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de Uruguay | Composition by RJ

A reader and admirer of Darío, Agustini met the poet in 1912 when he was travelling through South America as director of the journal Mundial. As a result of this meeting, there was a brief exchange of letters between the two poets during Darío’s stay in Buenos Aires and Montevideo. The letters are interesting for what they reveal of each writer’s attitude toward the other. There is a letter from Agustini to Darío, eloquent in its lucidity, where, while asking for his advice, she describes herself. Here are two excerpts from it:

I don’t know if you’ve ever come face to face with madness and fought with it in the harrowing solitude of a secretive spirit. There isn’t, there cannot be, a feeling more horrible. And the longing, the immense longing, to ask for help to face everything—to face the very Self, above all—from another spirit martyred in the same martyrdom.

The first time my madness overwhelmed me was before you. Why? No one should have struck me in my shyness as more imposing. How can I make you believe it, you who only know the courage of my unconscious? Perhaps because I recognize you as being of more divine essence than anyone I’ve met up to now, and therefore more indulgent. Sometimes I reproach myself for my boldness, and sometimes—why deny it?—I reproach myself for the disaster of my pride. To myself I seem be a beautiful statue with broken feet.

The letter concludes with two announcements: ‘In October I plan to put my neurosis in a sanatorium’ and ‘I have resolved to throw myself, in November or December, into the frightful abyss of marriage’. It ends with a request for a response, ‘a single paternal word’.

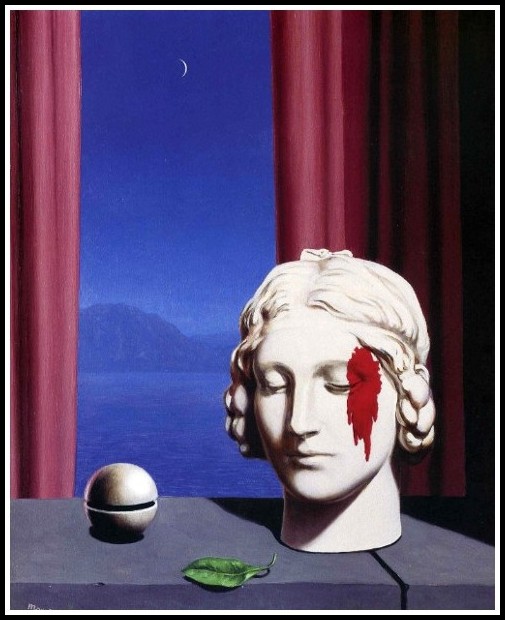

René Magritte, Memory, 1948

It is a tormented letter, excessive if you will, but one by an adult who recognizes a kindred spirit and asks for help. Darío’s response is remarkably depersonalized and curious in the distinction it makes between men and women. He writes:

Stay calm. Stay calm. Remember the principle of Marcus Aurelius: ‘Before all else, remain serene’. Believe above all in one thing: Destiny. The will itself is but subject to Destiny. Live, above all live, and fulfill your duty to joy, good joy. If genius in a man is a mountain of pain he must bear, in woman it is a gift that must be worn like a fiery robe.

Facile commentators on this correspondence agree that Darío’s letter had its effect on Agustini, who responded ‘in a more serene and resigned tone’. Clara Silva adds that Agustini’s second letter, ‘more reserved in tone, is also more literary’. Resigned maybe, literary certainly, but Agustini’s response is above all a disguise. She does what Manuel Ugarte, on another occasion, reproached her for: writing in such a way ‘that the ink serves as a mask’. Indeed, she presents herself as essentially fragile and ‘feminine’, speaking ‘with the heart’, while flirting with the man and poet she flatters with her feigned surrender.

Rubén Darío

Consider these two excerpts that reinforce the stereotype. Note the contrast in tone when speaking of her marriage between the first excerpt and the previous letter.

Since I’m planning on getting married very soon, I told my boyfriend I intend to continue my correspondence with you, the most brilliant and profound spiritual guide. Yesterday he casually asked me if I had written to you or received any news from you. In my embarrassment, I rattled on and on and came to imagine the impossible. Today I wonder, why? I think it’s because today I am another, or at least want to be another. I will be malleable, but be gentle. Sculpt me smiling.

Note, in the second excerpt (below), how Agustini continues to flatter Darío, telling him he is the only one in the world who gives her the ‘exquisite sensation of heightened artistic feeling’.

And you, Master, always give it to me, in every stanza, in every verse—sometimes even in a single word. And so intense, so dizzyingly, like that glorious day when, between a doll and a sweet, I sobbed reading your ‘Symphony in Gray’.

‘Between a doll and a sweet’: she is fully assuming (although not in baby talk) the girlishness that Ibsen highlighted in his plays. (Manuel Ugarte echoes Agustini’s girlish pose when, in one of his letters to her, he asks: ‘Do I deserve a sweet, a letter from you?’.)

John Everett Millais, Apple Blossoms (Spring), 1858 (detail)

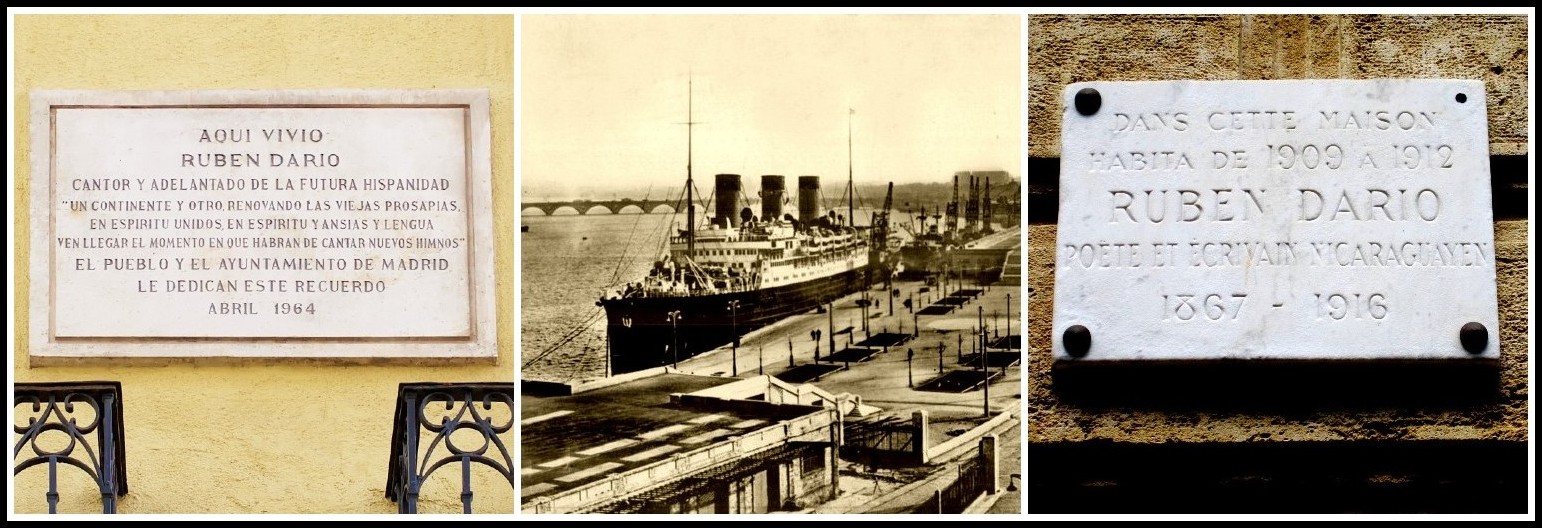

Perhaps it is an exaggeration to see this second letter from Agustini exclusively as a response to Darío’s shallow and indirect reply to her plea in which he put her—like other women who write—‘in her place’. Nevertheless, that the letter shows an awareness of the role she is playing—that both are playing—seems clear to me. Compare Agustini’s deliberate self-abasement and the concomitant exaltation of the Master with the laconic note devoid of embellishment in which she recorded ‘for posterity’ her last encounter with Darío as he was about to set sail for Europe:

Today Sunday 6 October at 10:20 a.m. I saw, aboard the Dutch steamer ‘Zeelandia’, docked at Dock A, Mr. Rubén Darío. He was wearing a light-colored suit and a ship officer’s cap. He held his hands behind his back and continuously licked and sucked his lips. He looked at the city for a few minutes and then turned toward the camera. At 10:32 the first whistle sounded. At 10:36 on Solís Street, passing Piedras, I met Professor Rodó who was heading towards the harbor.

Rubén Darío: Madrid & Paris | Photo of Madrid plaque: Antonello Dellanotte (detail)

II – DELMIRA AGUSTINI: ‘THE SWAN’ & ‘NOCTURNE’

I turn now to examine the poems and what they reveal: a different kind of encounter between Darío and Agustini, taking place in a domain where the roles are changed, where Agustini, no longer ‘La Nena’ but a writer, responds in a very different manner to her poetic precursor. I want to show how each poet offers their own distinctive interpretation of the legend of Leda and the swan, and by extension, of the swan itself as an iconic motif. In particular, I want to show how Agustini, in composing ‘The Swan’ and ‘Nocturne’ (The Empty Chalices, 1913), necessarily takes into account—and ‘corrects’—Darío’s precursor poem.

Adolf Erbsolp, Leda and the Swan, 1909

EL CISNE

Delmira Agustini

Pupila azul de mi parque

Es el sensitivo espejo

De un lago claro, muy claro!

Tan claro que a veces creo

Que en su cristalina pagina

Se imprime mi pensamiento.

Flor del aire, flor del agua,

Alma del lago es un cisne

Con dos pupilas humanas,

Grave y gentil como un principe;

Alas lirio, remos rosa

Pico en fuego, cuello triste

Y orgulloso, y la blancura

Y la suavidad de un cisne

El ave candida y grave

Tiene un maléfico encanto;

—Clavel vestido de lirio,

Trasciende a llama y milagro!

Sus alas blancas me turban

Como dos calidos brazos;

Ningunos labios ardieron

Como su pico en mis manos;

Ninguna testa ha caido

Tan languida en mi regazo;

Ninguna carne tan viva,

He padecido o gozado:

Viborean en sus venas

Filtros dos veces humanos!

THE SWAN

Delmira Agustini | Richard Jonathan

Blue eye of my park:

The sensitive mirror

Of a clear, very clear lake;

So clear that at times I believe

That on its transparent surface

My thoughts are printed as on a page.

Flower of the air, flower of the water,

A swan is the soul of the lake:

A swan with human eyes,

Princely, grave and kind

—Lily wings, legs of rose,

Fiery beak, neck sorrowful

And proud—and the whiteness

And the softness of a swan.

The solemn, spotless bird

Has a wicked charm;

—Carnation disguised as lily,

Beyond flame and miracle.

Holding me in a warm embrace,

His white wings unsettle me;

No lips have ever burned

Like his beak in my hands;

No head has ever fallen

As languidly into my lap;

No flesh so vital

Have I so relished in pleasure and in pain:

The bang of blood in his veins

Transports twice-human philters.

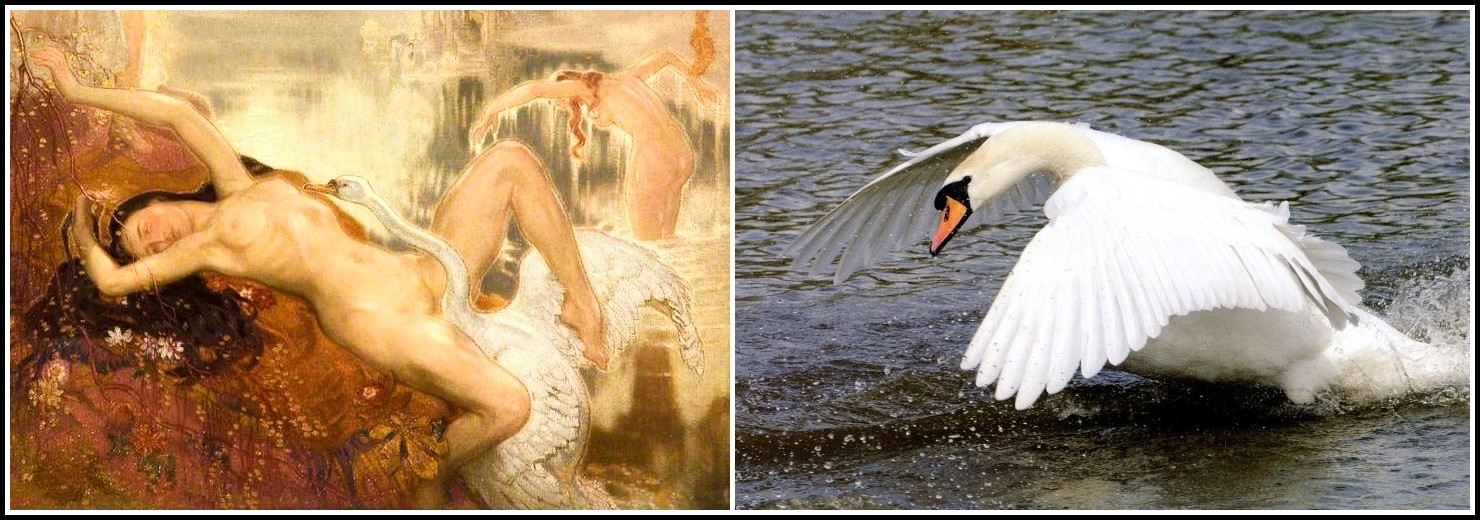

Rubens, Leda and the Swan, 1599 | Swan photo: Malcolm Schuyl

Del rubi de la lujuria

Su testa esta coronada;

Y va arrastrando el deseo

En una cauda rosada

Agua le doy en mis manos

Y él parece beber fuego;

Y yo parezco ofrecerle

Todo el vaso de mi cuerpo

Y vive tanto en mis sueños,

Y ahonda tanto en mi carne,

Que a veces pienso si el cisne

Con sus dos alas fugaces,

Sus raros ojos humanos

Y el rojo pico quemante,

Es solo un cisne en mi lago

O es en mi vida un amante

Al margen del lago claro

Yo le interrogo en silencio

Y el silencio es una rosa

Sobre su pico de fuego

Pero en su carne me habla

Y yo en mi carne le entiendo.

—A veces ¡toda! soy alma;

Y a veces ¡toda! soy cuerpo, —

Hunde el pico en mi regazo

Y se queda como muerto

Y en la cristalina pagina,

En el sensitivo espejo

Del lago que algunas veces

Refleja mi pensamiento,

El cisne asusta de rojo,

Y yo de blanca doy miedo!

With the ruby of luxury

His head is crowned;

In a train of incarnadine

He drags desire.

I give him water from my hands

And it’s fire he seems to drink;

The whole vessel of my body

I seem to lay before him.

He is so alive in my dreams,

He burrows so deeply into my flesh,

That at times I wonder whether the swan

With his evanescent wings,

His exquisite human eyes

And his burning red beak

Is less a swan in my lake

Than a lover in my life.

At the edge of the clear lake

I question him in silence,

And the silence is a rose

On his beak of fire.

But in his flesh he speaks to me

And I in my flesh understand him.

— Sometimes I am all soul,

And sometimes I am all body —

He buries his beak in my lap

And remains still as if dead.

And on the transparent page,

In the sensitive mirror

Of the lake that sometimes

Reflects my thoughts,

The swan frightens with its redness,

And I, with my whiteness, am frightening.

Swan photo: Malcolm Schuyl l Franz Russ the Younger (1844-1906), Leda and the Swan

Agustini’s reading of the swan is as sacrilegious as González Martínez’s famous sonnet, published three years earlier. Perhaps even more subversive: in González Martínez, the poem, clearly didactic, discards one icon to replace it with another. The swan that ‘does not feel / The soul of things, nor hear the landscape’s voice’ is replaced by the owl, interpreter of the mystery. In contrast, Agustini’s two poems do not discard, do not replace, but insist on semantizing the icon—and even the emblematic encounter of Leda and the swan—in another way. They break with Darío’s practice of proceeding by accretion, of not discarding—Darío neutralizes signs only to recharge them with meaning, in fulfillment of imaginative demands. Not in vain do these two Agustini poems belong to The Empty Chalices, a title that already announces, in contrast to the ‘full’ chalices of Darío (see, for example, The Amphorae of Epicurus), the divergent, inquisitorial purpose of the poems it overarches.

TUÉRCELE EL CUELLO AL CISNE

González Martínez

Tuércele el cuello al cisne de engañoso plumaje

que da su nota blanca al azul de la fuente;

él pasea su gracia no más, pero no siente

el alma de las cosas ni la voz del paisaje.

Huye de toda forma y de todo lenguaje

que no vayan acordes con el ritmo latente

de la vida profunda… y adora intensamente

la vida, y que la vida comprenda tu homenaje.

Mira al sapiente búho cómo tiende las alas

desde el Olimpo, deja el regazo de Palas

y posa en aquel árbol el vuelo taciturno…

Él no tiene la gracia del cisne, mas su inquieta

pupila, que se clava en la sombra, interpreta

el misterioso libro del silencio nocturno.

WRING THE NECK OF THE SWAN

González Martínez | Richard Jonathan

Wring the neck of the swan of deceptive plumage

That lends a touch of white to the fountain’s blue;

It glides its grace, no more, but does not feel

The soul of things, nor hear the landscape’s voice.

Flee from all form and all language

That does not match the underlying rhythm

Of the inner life; adore life intensely,

And may life understand your homage.

Look at the wise owl take wing

From Olympus, leave the lap of Pallas

And, alighting in a tree, end its silent flight.

It lacks the swan’s grace, but its restless

Pupil, in darkness content, elucidates

The silent night’s book of mysteries.

Owl photo: Dmitrii Zhodzishskii | Swan photo: Malcolm Schuyl

The emblematic character of the swan is established early in Darío’s work: in ‘Blasón’, to be precise, from the 1896 collection, Prosas profanas y otros poemas. A heraldic image, the swan is a symbol that, depending on the poem, works in different ways. A flexible symbol, Darío, with his usual tendency to add on rather than take away, loads it with all manner of meaning. To give a few examples, the swan (in Darío it is always the swan: he uses it as an archetype) is:

– culture (‘Blazon’)

– the new poetry (‘The Swan’)

– the enigma of artistic creation (‘I Seek a Form…’)

– eroticism (‘Leda’)

– Hispanicism (‘Swans I)

[‘Leda’ can be found three rows down; the four other poems mentioned here are presented at the bottom of this page.]

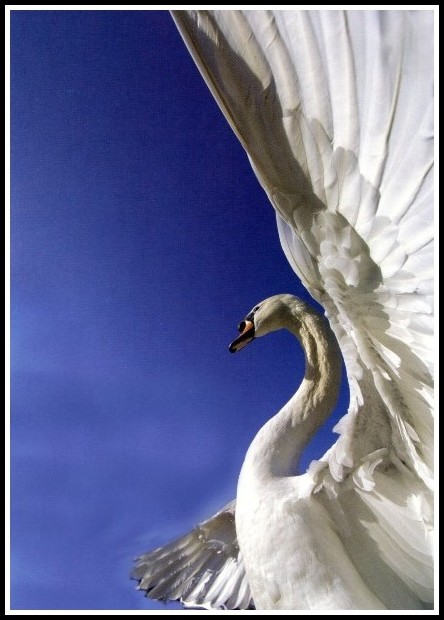

Photo: Malcolm Schuyl

By making her swan male, Agustini reduces the symbolic field: what is an emblem in Darío is shorn of culture and ‘discredited’ in Agustini. Her poem proceeds in inverse manner to that of Darío’s ‘Swans III’, ‘Swans IV’ and ‘Leda’ (all from Songs of Life and Hope), poems I shall consider as ‘pre-texts’ to Agustini’s poem. In Darío, the encounter between Leda and the swan is presented as a spectacle, a scene from a ritual, with its full charge of the sacred. The poem shows: both speaker and reader are ‘before the heavenly, supreme act’, as observers, worshippers and vicarious participants. This participation, expressed directly in ‘Leda’ with its scene of voyeurism—‘the screen of teeming foliage parts and the wild / green eyes of Pan stare out, wide with surprise’—is more indirect in ‘Swans IV’: ‘Melancholy of having loved / with the fountain of the grove nearby, / the luminous neck outstretched / between Leda’s white thighs!’, and is expressed directly again in ‘Swans III’, a poem in the first-person founded on identification: ‘For one moment, oh Swan, I will join my longings / with those of your two wings that once clasped Leda,’. In Darío, then, a scene already constructed, already framed and distanced by myth, is presented frankly or surreptitiously to our gaze—to be celebrated and to serve, perhaps, as a mirror for self-recognition.

LEDA

Rubén Darío

El cisne en la sombra parece de nieve;

su pico es de ámbar, del alba al trasluz;

el suave crepúsculo que pasa tan breve

las cándidas alas sonrosa de luz.

Y luego, en las ondas del lago azulado,

después que la aurora perdió su arrebol,

las alas tendidas y el cuello enarcado,

el cisne es de plata, bañado de sol.

Tal es, cuando esponja las plumas de seda,

olímpico pájaro herido de amor,

y viola en las linfas sonoras a Leda,

buscando su pico los labios en flor.

Suspira la bella desnuda y vencida,

y en tanto que al aire sus quejas se van,

del fondo verdoso de fronda tupida

chispean turbados los ojos de Pan.

LEDA

Rubén Darío | Lysander Kemp

The swan in shadow seems to be of snow;

his beak is translucent amber in the daybreak;

gently that first and fleeting glow of crimson

tinges his gleaming wings with rosy light.

And then, on the azure waters of the lake,

when dawn has lost its colors, then the swan,

his wings outspread, his neck a noble arc,

is turned to burnished silver by the sun.

The bird from Olympus, wounded by love, swells out

his silken plumage, and clasping her in his wings

he ravages Leda there in the singing water,

his beak seeking the flower of her lips.

She struggles, naked and lovely, and is vanquished,

and while her cries turn sighs and die away,

the screen of teeming foliage parts and the wild

green eyes of Pan stare out, wide with surprise.

Cornelis Bos, Leda and the Swan (after Michelangelo), 1555 | Swan photo: The Blowup

The dynamics of Agustini’s poem are very different. It is not an aspect of a well-known scene, it is not a dimension of the myth (not once does the name ‘Leda’ appear); instead, it is a first-person voice that actively generates a personal sphere, a purely artificial landscape (a common process in modernist poetry) that is the metonymic background of the self. ‘My park’, writes Agustini, ‘my lake’. Here is the first stanza, which opens with a metaphor undeniably reminiscent of Darío:

Pupila azul de mi parque

Es el sensitivo espejo

De un lago claro, muy claro!

Tan claro que a veces creo

Que en su cristalina pagina

Se imprime mi pensamiento.

Blue eye of my park:

The sensitive mirror

Of a clear, very clear lake;

So clear that at times I believe

That on its transparent surface

My thoughts are printed as on a page.

Photo: Satria Hutama

In this domain where the imaginary reigns, this insubstantial, almost chimerical realm—mirror, clear, crystalline—a swan begins to emerge. Although in the first stanza the poem presents the external characteristics of the prototypical Darian swan—prince, lily, rose, candid bird—right from the next stanza it is clear that the erotic impulse is driving the poem, gradually diverting the swan from its model. Thus Agustini’s swan is endowed with ‘two human eyes’, with ‘wicked charm’ and a ‘fiery beak’ (in contrast to the beak of ‘translucent amber’ of Darío’s swan) and his embrace is clearly sexual: ‘Holding me in a warm embrace / His white wings unsettle me.’ Note how these verses center the perspective of the poem. Here the disturbance of the encounter is not, as in Darío, in the observer outside the scene (spying eyes, Pan, the speaker, the reader) but in the ‘I’ itself, at once author of and actor in the scene. The woman (‘fevered Leda’ Monegal calls her) and not the swan, not the epicene reader, generates the growing erotic passion: she desires and communicates her desire. To simplify, Agustini utters—excessively, with ‘fierce femininity’ (Alfonsina Storni)—what Darío leaves aside. She gives voice to a feminine eroticism that in Darío is lost or ‘wasted’.

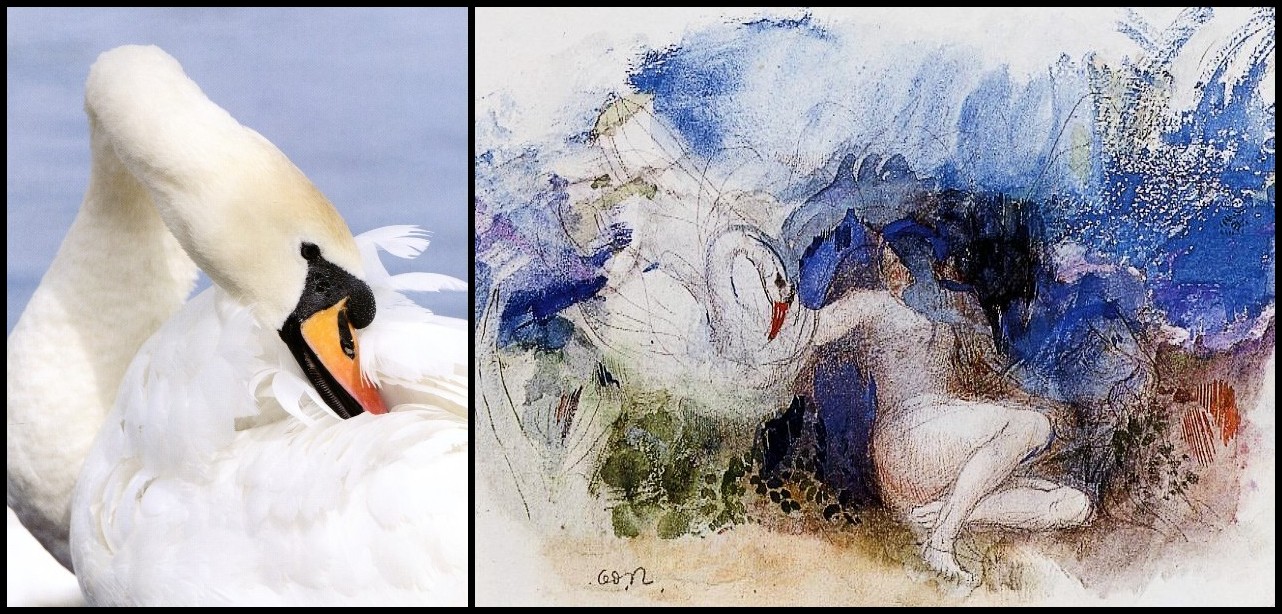

Swan photo: Malcolm Schuyl | Giambettino Cignaroli, Leda and the Swan, 1766

We read in the last stanza of Darío’s ‘Leda’: ‘She struggles, naked and lovely, and is vanquished, / and while her cries turn sighs and die away…’. Unlike in Darío, in Agustini eroticism needs to be spoken, to be inscribed—not as the sighs, lost in the wind, of one defeated, but as triumphant and frightening pleasure.

William Shackleton, Leda and the Swan, 1928 (detail) | Swan photo: Malcolm Schuyl

In Agustini, the eroticized ‘I’ infects the poem with desire: there is an eroticism of disequilibrium, of the labile, of movement, while in Darío the eroticism is of the fixed, of what attempts to be fixed. In this regard, see, for example, the powerful sexual image that, after the geographical vertigo of the preceding stanzas, serenely closes ‘Divagación.

RUBÉN DARÍO: DIVAGACIÓN | DIGRESSION – THE LAST STANZA

Sé mi reina de Saba, mi tesoro;

descansa en mis palacios solitarios.

Duerme. Yo encenderé los incensarios.

Y junto a mi unicornio cuerno de oro,

tendrán rosas y miel tus dromedarios.

Be my queen of Sheba, my treasure;

Rest in my lonely palaces.

Sleep. I will light the censers.

And next to my golden-horn unicorn,

Your dromedaries will have roses and honey.

‘And next to my golden-horn unicorn, your dromedaries will have roses and honey.’

Alfonsina Storni astutely pointed out that Agustini possessed ‘to an exalted degree the feminine qualities of passion, imagination and a horror of immobility’. In connection with this dynamic of desire that inspirits the swan in Agustini as it does not in Darío, it is worth noting how, starting with the embrace already mentioned, tokens of ardor, evident in the occurrences of ‘fire’ and instances of ‘red’, proliferate in the poem: ‘No lips have ever burned’, ‘The bang of blood in his veins / Transports twice-human philters’, ‘his burning red beak’, ‘his fiery beak’, ‘frightens with its redness’, ‘ruby’, ‘fire’, ‘red’. Compare this mounting fever, this headlong rush of red, with the draining of color that Darío employs as a distancing device in ‘Leda’, making the moment of rape, paradoxically, the least bloody:

Y luego, en las ondas del lago azulado,

después que la aurora perdió su arrebol,

las alas tendidas y el cuello enarcado,

el cisne es de plata, bañado de sol.

And then, on the azure waters of the lake,

when dawn has lost its colors, then the swan,

his wings outspread, his neck a noble arc,

is turned to burnished silver by the sun.

Swan photo: Malcolm Schuyl | Charles-Joseph Natoire, Leda and the Swan, 1735

Darío’s eroticism is undemanding whereas Agustini’s is urgent and fearsome: ‘The swan frightens with its redness, / And I, with my whiteness, am frightening’. By a kind of erotic vampirism—‘I give him water from my hands / And it’s fire he seems to drink; / The whole vessel of my body / I seem to lay before him’—the desiring self, at the expense of ‘the whole vessel of my body’, has been emptied of substance. The usual erotic image—the male filling up the glorified female body—that we find not only in Darío’s references to Leda (‘your sweet womb’, ‘Leda’s sky-blue egg’) but throughout his poetry, is subverted in Agustini: It is the ‘I’, the woman, who has filled the white swan—the translucent ‘flower of the air, flower of the water’—giving it substance (blood, fire) and at the same time, wasting away.

Swan photo: Malcolm Schuyl | Odilon Redon (1840-1916), Leda and the Swan

Note that this transfer of substance, an indication of fullness in Darío (a ‘good expenditure’, so to speak) indicates something very different in Agustini, where the self is spent by giving itself (‘I’, ’whiteness’ [bloodless]), draining the desiring object of its desire: ‘He buries his beak in my lap / And remains still as if dead’. This curious erotic collaboration, freely assumed—‘But in his flesh he speaks to me / And I in my flesh understand him’—decisively distances us from Leda and the swan as seen by Darío. Indeed, it leaves us clearly on the other side of harmony (‘white urns of harmony’, ‘Swans IV’), on the other side of happiness (‘Love will be happy’, ‘Swans III’), on the other side of ‘celestial melancholy’ (‘Swans IV’), in full and terrible excess where pleasure is confused with—where pleasure is—pain.

Swan photo: Malcolm Schuyl | Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre (1714–1789), Leda and the Swan

LOS CISNES III

Rubén Darío

Por un momento, oh Cisne, juntaré mis anhelos

a los de tus dos alas que abrazaron a Leda,

y a mi maduro ensueño, aún vestido de seda,

dirás, por los Dioscuros, la gloria de los cielos.

Es el otoño. Ruedan de la flauta consuelos.

Por un instante, oh Cisne, en la obscura alameda

sorberé entre dos labios lo que el Pudor me veda,

y dejaré mordidos Escrúpulos y Celos.

Cisne, tendré tus alas blancas por un instante,

y el corazón de rosa que hay en tu dulce pecho

palpitará en el mío con su sangre constante.

Amor será dichoso, pues estará vibrante

el júbilo que pone al gran Pan en acecho

mientras su ritmo esconde la fuente de diamante.

THE SWANS III

Rubén Darío | Lysander Kemp

For one moment, oh Swan, I will join my longings

with those of your two wings that once clasped Leda,

and you, in silk, will tell my maturing dreams,

through Castor and Pollux, of all the heavens’ glory.

It is autumn now. The flute pours out its counsels.

For one instant, oh Swan, in the darkening grove,

I will drink with my two lips what modesty

forbids, disdaining scruples and suspicions.

Swan, for an instant your white wings will be mine,

and the roselike heart within your glorious breast

will beat within my own with your strong blood.

Love will be happy, because of the vibrant joy

that Pan will feel as he spies from his green ambush,

and the diamantine fount will hide a rhythm.

François Boucher, Leda and the Swan, 1740 | Swan photo: Malcolm Schuyl

LOS CISNES IV

Rubén Darío

Antes de todo, gloria a ti, Leda!

Tu dulce vientre cubrió de seda

el Dios. Miel y oro sobre la brisa!

µ Sonaban alternativamente

flauta y cristales, Pan y la fuente.

Tierra era canto, Cielo sonrisa!

Ante el celeste, supremo acto,

dioses y bestias hicieron pacto.

Se dio a la alondra la luz del día,

se dio a los búhos sabiduría

y melodía al ruiseñor.

A los leones fue la victoria,

para las águilas toda la gloria

y a las palomas todo el amor.

Pero vosotros sois los divinos

príncipes. Vagos como las naves,

inmaculados como los linos,

maravillosos como las aves!

En vuestros picos tenéis las prendas

que manifiestan corales puros.

Con vuestros pechos abrís las sendas

que arriba indican los Dioscuros.

Las dignidades de vuestros actos,

eternizadas en lo infinito,

hacen que sean ritmos exactos,

voces de ensueños, luces de mito.

De orgullo olímpico sois el resumen,

oh, blancas urnas de la armonía!

Ebúrneas joyas que anima un numen

con su celeste melancolía.

Melancolía de haber amado

junto a la fuente de la arboleda,

el luminoso cuello estirado

entre los blancos muslos de Leda!

THE SWANS IV

Rubén Darío | W. Derusha & A. Acereda

First of all, glory to you, Leda!

Your sweet womb was covered in silk

by the God. Honey and gold on the breeze!

Alternately

flute and crystals sounded, Pan and the fountain.

Earth was a song, Heaven a smile!

In the presence of the heavenly, supreme act,

gods and beasts made a pact.

The lark was given the daylight,

the owls were given insight,

and the nightingale, melodies.

To the lions went victory,

for the eagles all the glory,

and to the doves all the love.

But you all are the divine

princes. Drifting like ships,

immaculate as flax,

wondrous as birds.

In your bills you have the qualities

which pure corals manifest.

With your breasts you open the pathways

which the Dioscuri indicate up above.

The dignity of your acts,

everlasting in infinity,

make these be exact rhythms:

voices of reverie, lights of myth.

You are the condensation of Olympic pride,

O white urns of harmony!

Eburnean jewels which a numen animates

with its celestial melancholy.

Melancholy of having loved

with the fountain of the grove nearby,

the luminous neck outstretched

between Leda’s white thighs!

Swan photo: Drazen Neske | François Boucher, Leda and the Swan, 1742

Pleasure is pain: In Agustini’s posthumous collection, The Rosary of Eros, in ‘Your Love, Slave’ and ‘Mouth to Mouth’, the instrument of desire reappears under the sign of pleasure-pain. ‘A raven’s beak with the fragrance of roses’, we find in the first, and in the second: ‘Red beak of the vulture of desire / Your blood and soul inside my mouth, / From your long and resounding pecking / A sore sprouted like a rock flower’.

Vulture photo: Andrey Tikhonovskiy

III – ‘NOCTURNE’: DELMIRA AGUSTINI’S SECRET FAREWELL

There is a second poem by Delmira Agustini that involves the swan. It can be read, I believe, as a definitive and secret farewell. Significantly, it is titled ‘Nocturne’.

NOCTURNO

Delmira Agustini

Engarzado en la noche el lago de tu alma,

Diríase una tela de cristal y de calma

Tramada por las grandes arañas del desvelo.

Nata de agua lustral en vaso de alabastros;

Espejo de pureza que abrillantas los astros

Y reflejas la sima de la Vida en un cielo

Yo soy el cisne errante de los sangrientos rastros,

Voy manchando los lagos y remontando el vuelo.

NOCTURNE

Delmira Agustini | Richard Jonathan

Set in the night, the lake of your soul

Is, one would say, a gauze of crystal and calm

Woven by a thousand spiders of sleeplessness.

A skim of lustral water in an alabaster vessel,

A mirror of purity that brightens the stars:

In the sky you reflect the abyss of Life.

I am the wandering swan of the bloody wake,

Before taking wing I stain a lake.

The ‘inner realm’ (Darío, Profane Hymns and Other Poems) is reduced here to its simplest expression: a lake, a swan, a ‘you’ and an ‘I’. The calm lake, ritualized and arrested in time, has a tranquility rare in Agustini—set, crystal, lustral water, alabaster vessel, mirror—as if magnified in the transparent night. The quietude of this symbolic lake—‘lake of your soul’—is finally troubled by a discordant ‘I’ that is the swan. The swan (and not a swan) is a destroyer of harmony, a violator of purity, a defiler: it stains, it blurs, it rearranges, and then it takes flight. In Agustini there is a total identification with the swan, the swan changed in symbolic sign, whereas in Darío the swan is never finally the emblem of the ‘I’.

Delmira Agustini | Swan photos: Malcolm Schuyl

One question remains. To whom is ‘Nocturne’ addressed, who is the ‘you’ invoked? The answer may be found, I believe, if we link this poem to ‘I Seek a Form’, the sonnet that closes Darío’s Profane Hymns and Other Poems.

YO PERSIGO UNA FORMA

Rubén Darío

Yo persigo una forma que no encuentra mi estilo,

botón de pensamiento que busca ser la rosa;

se anuncia con un beso que en mis labios se posa

al abrazo imposible de la Venus de Milo.

Adornan verdes palmas el blanco peristilo;

los astros me han predicho la visión de la Diosa;

y en mi alma reposa la luz como reposa

el ave de la luna sobre un lago tranquilo.

Y no hallo sino la palabra que huye,

la iniciación melódica que de la flauta fluye

y la barca del sueño que en el espacio boga;

y bajo la ventana de mi Bella-Durmiente,

el sollozo continuo del chorro de la fuente

y el cuello del gran cisne blanco que me interroga.

I SEEK A FORM

Rubén Darío | Lysander Kemp

I seek a form that my style cannot discover,

a bud of thought that wants to be a rose;

it is heralded by a kiss that is placed on my lips

in the impossible embrace of the Venus de Milo.

The white peristyle is decorated with green palms;

the stars have predicted that I will see the goddess;

and the light reposes within my soul like the bird

of the moon reposing on a tranquil lake.

And I only find the word that runs away,

the melodious introduction that flows from the flute,

the ship of dreams that rows through all space,

and, under the window of my sleeping beauty,

the endless sigh from the waters of the fountain,

and the neck of the great white swan, that questions me.

I maintain that Darío’s poem underlies Agustini’s. I suggest one read ‘Nocturne’ as a violent and iconoclastic response to a master whose poetry Agustini has separated herself from. And finally (to continue with the speculations that are the shameful pleasure of the critic) I would like to see, in the relation between the two poems, the cipher of the true dialogue that took place between Agustini and Darío: beyond the exchange between the Master and ‘La Nena’, a dialogue between poems.

Venus de Milo: Louvre | Rose: Chirag Saini | Swan: Robert Woeger

SYLVIA MOLLOY: BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

Courtesy of Asymptote Journal

Sylvia Molloy (b. 1938, Buenos Aires) is a novelist, essayist, and leading literary critic of Latin American literature. She is Albert Schweitzer Professor of Humanities Emerita at New York University, where she taught Latin American and comparative literatures and established the Creative Writing in Spanish Program. Her critical work includes La Diffusion de la littérature hispano-américaine en France au XXe siècle; Las letras de Borges; At Face Value: Autobiographical Writing in Spanish America; Hispanisms and Homosexualities; Poéticas de la distancia, and Poses de fin de siglo. She is also the author of two novels, En breve cárcel and El común olvido, and several books of short prose pieces: Varia imaginación, Desarticulaciones, Citas de lectura, and Vivir entre lenguas. She has been a fellow of the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Social Science Research Council, and the Civitella Ranieri Foundation.

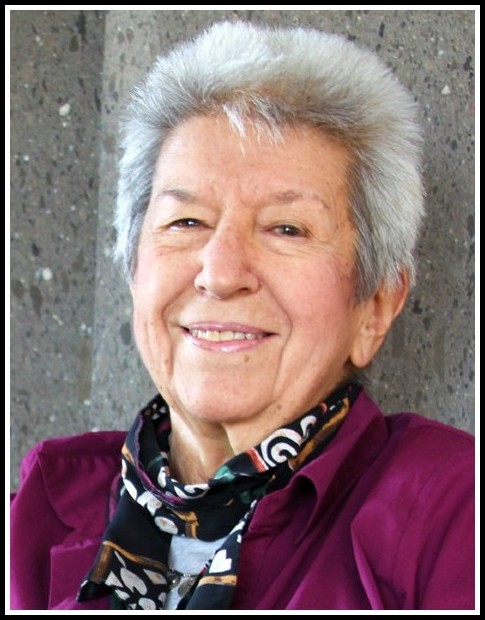

Sylvia Molloy | Photo: Javier Narváez

PART II

DELMIRA AGUSTINI: EL ROSARIO DE EROS | THE ROSARY OF EROS

A New Translation by Richard Jonathan

Delmira Agustini – The Rosary of Eros | Translated by Richard Jonathan

I. CUENTAS DE MÁRMOL

CUENTAS DE MÁRMOL

Delmira Agustini

Yo, la estatua de mármol con cabeza de fuego,

Apagando mis sienes en frío y blanco ruego…

Engarzad en un gesto de palmera o de astro

Vuestro cuerpo, esa hipnótica alhaja de alabastro

Tallada a besos puros y bruñida en la edad;

Sereno, tal habiendo la luna por coraza;

Blanco, más que si fuerais la espuma de la Raza,

Y desde el tabernáculo de vuestra castidad,

Nevad a mí los lises hondos de vuestra alma;

Mi sombra besará vuestro manto de calma,

Que creciendo, creciendo me envolverá con Vos;

Luego será mi carne en la vuestra perdida…

Luego será mi alma en la vuestra diluida…

Luego será la gloria… y seremos un dios!

—Amor de blanco y frío,

Amor de estatuas, lirios, astros, dioses…

¡Tú me los des, Dios mío!

BEADS OF MARBLE

Delmira Agustini | Richard Jonathan

I, the marble statue with a head of fire

Dousing my temples in cold and white, pray.

In a silhouette of palm tree or star

Set your body, that hypnotic alabaster jewel

Carved by pure kisses and polished by time.

The moon your breastplate, you are serene,

Whiter than if you were the spume of the Race.

Now from the tabernacle of your chastity

Let fall like snow the deep lilies of your soul.

My shadow will kiss your veil of calm

Which, looming ever larger, will enfold me in you.

Then my flesh will be lost in yours.

Then my soul will be diffused in yours.

Then glory will abound and a god we will be!

—Love of white and cold,

Love of statues, lilies, stars and gods—

Oh God, give it to me!

Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Cristo Crucificado, 1700 | Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, La Dolorosa, 1665

II. CUENTAS DE SOMBRA

CUENTAS DE SOMBRA

Delmira Agustini

Los lechos negros logran la más fuerte

Rosa de amor; arraigan en la muerte.

Grandes lechos tendidos de tristeza,

Tallados a puñal y doselados

De insomnio; las abiertas

Cortinas dicen cabelleras muertas;

Buenas como cabezas

Hermanas son las hondas almohadas:

Plintos del Sueño y del Misterio gradas.

Si así en un lecho como flor de muerte,

Damos llorando, como un fruto fuerte

Maduro de pasión, en carnes y almas,

Serán especies desoladas, bellas,

Que besen el perfil de las estrellas

Pisando los cabellos de las palmas!

—Gloria al amor sombrío,

Como la Muerte pudre y ennoblece

¡Tú me lo des, Dios mío!

BEADS OF DARKNESS

Delmira Agustini | Richard Jonathan

Black beds nourish best

The rose of love: it takes root in death.

Huge beds blanketed in sadness,

Carved by a dagger and canopied

By insomnia. Drawn curtains

Betray dead hair.

Deep twin pillows

Are good sisterly heads:

Plinths of Dream and Mystery, steps.

And so, if in our flower-of-death bed

We bring forth, crying, a heady fruit

Bearing the blush of passion, in spirit and flesh,

It will be of a beautiful, desolate kind

Which, treading on the tresses of the palm trees,

Kisses the silhouette of the stars.

Hail dark love!

Like Death it rots and ennobles.

Oh God, give it to me!

María Izquierdo, Viernes de Dolores, 1945 (detail) | Paul Gauguin, The Yellow Christ, 1889 (detail)

III. CUENTAS DE FUEGO

CUENTAS DE FUEGO

Delmira Agustini

Cerrar la puerta cómplice con rumor de caricia,

Deshojar hacia el mal el lirio de una veste…

—La seda es un pecado, el desnudo es celeste;

Y es un cuerpo mullido un diván de delicia.

— Abrir brazos… así todo ser es alado,

O una cálida lira dulcemente rendida

De canto y de silencio… más tarde, en el helado

Más allá de un espejo como un lago inclinado,

Ver la olímpica bestia que elabora la vida…

Amor rojo, amor mío;

Sangre de mundos y rubor de cielos…

¡Tú me lo des, Dios mío!

BEADS OF FIRE

Delmira Agustini | Richard Jonathan

To close the complicit door with the rustle of a caress,

To strip down to evil the lily of a dress

—Silk is a sin, nakedness divine,

And to luxuriate in a soft body is heaven.

Open arms: all creatures are winged,

Or the silence and song drawn from

A mellow lyre. Later, in the frozen

Beyond of a tilted mirror-lake,

See the Olympian beast who elaborates life

Red love, love of mine,

Blood of worlds and blush of skies

—Oh God, give it to me!

El Greco, Christ Crucified, 1611 (detail) | Ecuador, The Seven Sorrows of Mary, 1830 (detail)

IV. CUENTAS DE LUZ

CUENTAS DE LUZ

Delmira Agustini

Lejos como en la muerte

Siento arder una vida vuelta siempre hacia mí,

Fuego lento hecho de ojos insomnes, más que fuerte

Si de su allá insondable dora todo mi aquí.

Sobre tierras y mares su horizonte es mi ceño,

Como un cisne sonámbulo duerme sobre mi sueño

Y es su paso velado de distancia y reproche

El seguimiento dulce de los perros sin dueño

Que han roído ya el hambre, la tristeza y la noche

Y arrastran su cadena de misterio y ensueño.

Amor de luz, un río

Que es el camino de cristal del Bien.

¡Tú me lo des, Dios mío!

BEADS OF LIGHT

Delmira Agustini | Richard Jonathan

From afar as if in death

I feel the burning of a life always turned toward me;

A quiet fire of watchful eyes, all the more piercing

If from its impenetrable elsewhere it gilds my presence.

Upon lands and seas its horizon is my frown;

Somnambulant swan, it sleeps upon my dream.

Its veiled movement of distance and reproach

Is the gentle chase of dogs whose masters have died;

They have already gnawed on hunger, sadness and night,

And now, trailing their chain of mystery and dream, they stray.

Love of light, a river:

The glittering path of Good.

Oh God, give it to me!

Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Cristo Crucificado, 1600 | Nero di Bicci, The Ascension of the Virgin, 1465 (detail)

V. CUENTAS FALSAS

CUENTAS FALSAS

Delmira Agustini

Los cuervos negros sufren hambre de carne rosa;

En engañosa luna mi escultura reflejo,

Ellos rompen sus picos, martillando el espejo,

Y al alejarme irónica, intocada y gloriosa,

Los cuervos negros vuelan hartos de carne rosa.

Amor de burla y frío

Mármol que el tedio barnizó de fuego

O lirio que el rubor vistió de rosa,

Siempre lo dé, Dios mío…

O rosario fecundo,

Collar vivo que encierra

La garganta del mundo.

Cadena de la tierra

Constelación caída.

O rosario imantado de serpientes,

Glisa hasta el fin entre mis dedos sabios,

Que en tu sonrisa de cincuenta dientes

Con un gran beso se prendió mi vida:

Una rosa de labios.

FALSE BEADS

Delmira Agustini | Richard Jonathan

The crows are crying for rosy flesh;

The misleading moon is a mirror for my sculpture.

The crows, hammering the mirror, break their beaks,

And as I walk away they, sated on rosy flesh,

Fly off in a volley of black—sardonic, aloof, dazzling

Love of derision and cold

Marble that tedium has glazed with fire,

O lily in your blush of pink—

Give it to me always, dear God!

O fruitful rosary:

Vital necklace encircling

The throat of the world.

Chain of the earth,

Fallen constellation.

O rosary magnetized by serpents,

Slither until the end between my knowing fingers,

That in your smile of fifty teeth

My life is set ablaze with a big kiss:

A rose of lips

Luis de Morales, Virgin Dolorosa, 1565 | Juan Carreno de Miranda, Christ Crucified, 1665 (detail)

DELMIRA AGUSTINI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 7: Ximena

Marietta, I’m sitting at a table in an all-night bar, soothed by the mint-green walls and cool Atlantic breeze. In a corner, two prostitutes are playing chess. The one with a sparkle in her eyes is losing to the one with a sultry languour. Opposite me sits Ximena. We’re drinking a dark, brooding Oloroso. More than the nudity of her shoulders, I like her centre-parted hair that leaves her forehead bare; more than the ripeness of her lips, I like her full-throated laughter. She’s studying Maritime Archeology and the History of Seafaring at the University of Cádiz. Wants to work in cultural heritage management. She’s from Montevideo. Her grand-parents fled Italy in 1943, just before the Nazis raided the Jewish ghetto in Rome after the Italian capitulation. It was inevitable we’d meet: Not only did she recognize me, she’d just bought, at an all-night bookshop, a bilingual edition of Holograms of Happenstance (a collection of my haiku, with watercolours by Liselotte). I’d come here because sleep wouldn’t come; it wasn’t long before my mind became a magic lantern, turning up memories of you. I’d just finished writing up the third one when Ximena approached me.

Ariadna Gil : Ximena

After I’d signed Holograms—To Ximena, from a man who still dreams of ocean voyages under the stars, of Pedro de Sintra, Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco de Gama—she told me of her life in Montevideo (sitting on her patio reading Baudelaire, the scent of wisteria no match for the perfume of Les Fleurs du mal). I then asked her to read me something from the second book she’d bought, El rosario de Eros by Delmira Agustini. I remember only an image of a marble statue with a head of fire, and I remember the poet’s story: Divorced one month after her wedding, she declared, ‘Marriage is a vulgarity’. Then, shifting from wife to lover, she began seeing her husband in a bordello. Before killing himself, the bastard shot her dead. In the onyx of Ximena’s eyes the murder still smouldered, their watery black took on a fiery glow.

Delmira Agustini & Enrique Job Reyes – Police photos taken at the scene of the crime, 6 July 1914

Ximena then asked what I’d been writing; I passed her my notebook. She read the first entry:

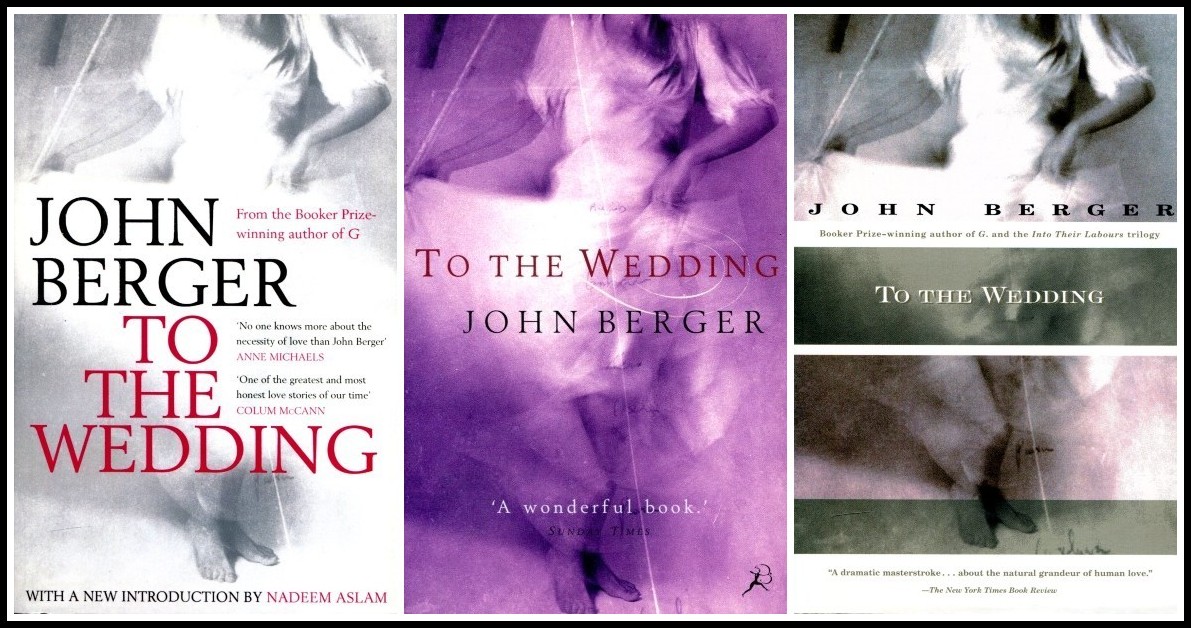

Sitting sideways in your reading chair, your legs slung over the armrest, you hold the phone to your cheek and explain to Pascale how to make that lasagna dish you served at dinner on Sunday. Stretched out on the sofa, I lay To the Wedding down and watch you, moved. Moved by this fleeting moment, moved by the innocence of your beauty in the light of the etched-glass lamp.

John Berger, To the Wedding

Outside the living room, the streetlights conspire with the twilight to persuade me I’m dreaming. After all these years, Marietta, they’ve finally succeeded: Suspended in that moment now, I am a floating feather—one puff and you’d blow me away.

̶ I see, Sprague, that for you marriage is not a vulgarity.

̶ No, Ximena, it’s not.

̶ May I read another one?

̶ Yes.

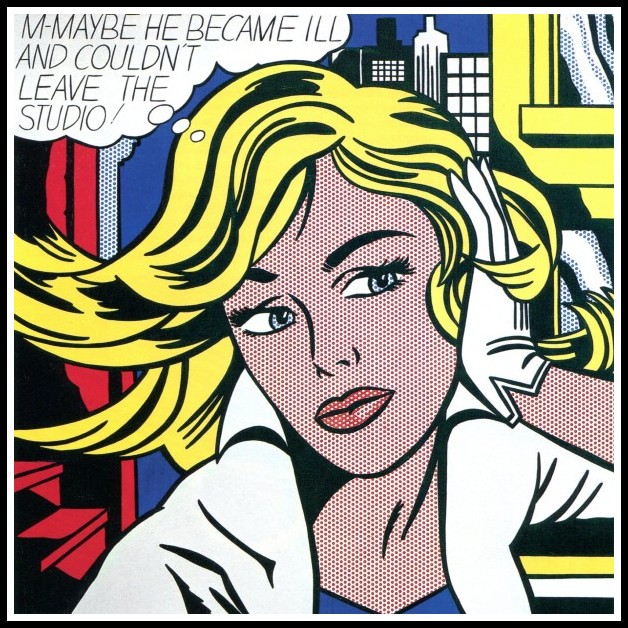

Roy Lichtenstein, M-Maybe, 1965

She then read the second entry:

‘Puma’ in glitter sparkling on your chest, your breasts flattened by a sports bra, you stand at the bar separating dining room from kitchen and drink from a bottle of Heineken. A thin film of sweat brings a glow to your skin and sticks a strand of hair to your cheek. Once again I am overcome by your virile femininity, once again my bowl brims over with your beauty. The sunlight conspires with the blinds to persuade me I’m just a pilgrim who’s walked a mile too many. Was it just an hallucination, then, when I stepped up behind you and kissed the hollow behind your ear? Sunlight and blind proclaim their victory as I hover in that moment: A flick of your finger would suffice, Marietta, to knock me down now.

̶ Are you still together?

̶ No.

̶ May I read one more?

̶ Okay.

Roy Lichtenstein, Oh Jeff, 1964

She then read the third entry:

Under the skylight, as snow whirls outside, you stand in your bodysuit and stay-ups, ironing your shirt. A beep announces an email. You sip your coffee as you read it: Again the headhunter—he just won’t stay away. In half an hour your taxi will be here. You finish ironing the shirt then slip it on; you step into your skirt and zip it closed. Your headband holding back your hair, before the mirror you put on your make-up. And then, giving your hair a final brushing, you decide to pin it up after all. Along the perimeter of the mirror, as you gather your hair in your hands, the tube of continuous light conspires with the amber of your eyes to persuade me I’m still a sleeper. When you twirled your hair and stuck in the stick, was that pang in my heart just my imagination? I succumb to the amber of your eyes, I surrender to the continuous light: A bat of your eyelids now, Marietta, would obliterate me.

̶ Such lightness! Did things get heavy, in the end?

̶ No. ‘What is good is light; everything divine runs on delicate feet.’ Marietta is divine.

Roy Lichtenstein, Yellow and Green Brushstrokes, 1966

Outside the café we walked some way together; then, there where her centre-parted hair leaves her forehead bare, I kissed Ximena goodbye.

Into sandstone walls as I walk the streets, daybreak mixes gold dust and magenta. At the market, a woman fetches buckets of roses from a van, men unload a fish truck. The day summons me to renew my senses, the day commands me to refresh my soul. I will go for a café solo and ensaimada, I will return to my hotel for a shower and a shave. Then I’ll walk past the fortress, I’ll walk past the beach, I’ll walk along the shore to where the wild grass grows. There, before structuring my compulsion to recall, I’ll lie down and give free rein to my reverie. If I become regretful, remind me you are not a bird that flew; if I get sentimental, give me another turn of the screw: Marietta, hear me now, that I may honour you!

Roy Lichtenstein, Modern Art II, 1996

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

DELMIRA AGUSTINI: CODA

Graciela Aletta de Sylvas

From Graciela Aletta de Sylvas, ‘El erotismo de Delmira Agustini’ (Biblioteca virtual Miguel de Cervantes). Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Writing was the game that Agustini played with death. In the face of sidelining and silencing, in a world of intellectual men, the epistolary genre and the arduous craft of literature were the defences that safeguarded her voice.

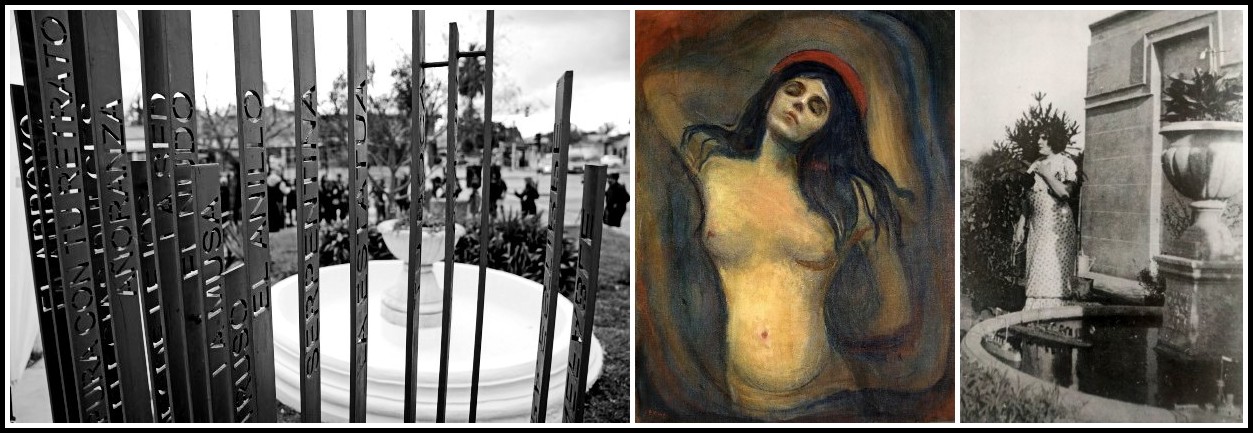

Delmira Agustini Memorial Fountain | Edvard Munch, Madonna, 1895 | Delmira Agustini, Summer Residence, Sayago

RUBÉN DARÍO

FOUR OTHER POEMS REFERENCED IN ‘TWO READINGS OF THE SWAN’

I. BLASÓN

BLASÓN

Rubén Darío

El olímpico cisne de nieve

con el ágata rosa del pico

lustra el ala eucarística y breve

que abre al sol como un casto abanico.

De la forma de un brazo de lira

y del asa de un ánfora griega

es su cándido cuello, que inspira

como prora ideal que navega.

Es el cisne, de estirpe sagrada,

cuyo beso, por campos de seda,

ascendió hasta la cima rosada

de las dulces colinas de Leda.

Blanco rey de la fuente Castalia,

su victoria ilumina el Danubio;

Vinci fue su varón en Italia;

Lohengrín es su príncipe rubio.

BLAZON

Rubén Darío | Lysander Kemp

The snow-white Olympic swan,

with beak of rose-red agate,

preens his eucharistic wing,

which he opens to the sun like a fan.

His shining neck is curved

like the arm of a lyre,

like the handle of a Greek amphora,

like the prow of a ship.

He is the swan of divine origin

whose kiss mounted through fields

of silk to the rosy peaks

of Leda’s sweet hills.

White king of Castalia’s fount,

his triumph illumines the Danube;

Da Vinci was his baron in Italy;

Lohengrin is his blond prince.

Leonardo da Vinci, Studies for ‘Leda and the Swan’, 1505 | Lohengrin, Deutsche Oper Berlin, 2012

Su blancura es hermana del lino,

del botón de los blancos rosales

y del albo toisón diamantino

de los tiernos corderos pascuales.

Rimador de ideal florilegio,

es de armiño su lírico manto,

y es el mágico pájaro regio

que al morir rima el alma en un canto.

El alado aristócrata muestra

lises albos en campo de azur,

y ha sentido en sus plumas la diestra

de la amable y gentil Pompadour.

Boga y boga en el lago sonoro

donde el sueño a los tristes espera,

donde aguarda una góndola de oro

a la novia de Luis de Baviera.

Dad, condesa, a los cisnes cariño;

dioses son de un país halagüeño,

y hechos son de perfume, de armiño,

de luz alba, de seda y de sueño.

His whiteness is akin to linen,

to the buds of white roses,

to the diamantine white

of the fleece of an Easter lamb.

He is the poet of perfect verses,

and his lyric cloak is of ermine;

he is the magic, the regal bird

who, dying, rhymes the soul in his song.

This wingèd aristocrat displays

white lilies on a blue field;

and Pompadour, gracious and lovely,

has stroked his feathers.

He rows and rows on the lake

where dreams wait for the unhappy,

where a golden gondola waits

for the sweetheart of Louis of Bavaria.

Countess, give the swans your love,

for they are gods of an alluring land

and are made of perfume and ermine,

of white light, of silk, and of dreams.

Ludwig II of Bavaria (Click/Tap: Ludwig II of Bavaria’s Queer Swans) | Madame de Pompadour

II. LOS CISNES I

LOS CISNES I

Rubén Darío

¿Qué signo haces, oh Cisne, con tu encorvado cuello

al paso de los tristes y errantes soñadores?

¿Por qué tan silencioso de ser blanco y ser bello,

tiránico a las aguas e impasible a las flores?

Yo te saludo ahora como en versos latinos

te saludara antaño Publio Ovidio Nasón.

Los mismos ruiseñores cantan los mismos trinos,

y en diferentes lenguas es la misma canción.

A vosotros mi lengua no debe ser extraña.

A Garcilaso visteis, acaso, alguna vez

Soy un hijo de América, soy un nieto de España

Quevedo pudo hablaros en verso en Aranjuez

SWANS I

Rubén Darío | W. Derusha & A. Acereda

What sign do you give, O Swan, with your curving neck

when the sad and wandering dreamers pass?

Why so silent from being white and being beautiful,

tyrannical to the waters and impassive to the flowers?

I greet you now as in Latin verses

Publius Ovid Naso greeted you long ago.

The same nightingales sing the same trills,

and in different languages it’s the same song.

To you my language should not be foreign.

Perhaps you saw Garcilaso, once

I’m a son of America, I’m a grandson of Spain

Quevedo spoke to you in verse in Aranjuez

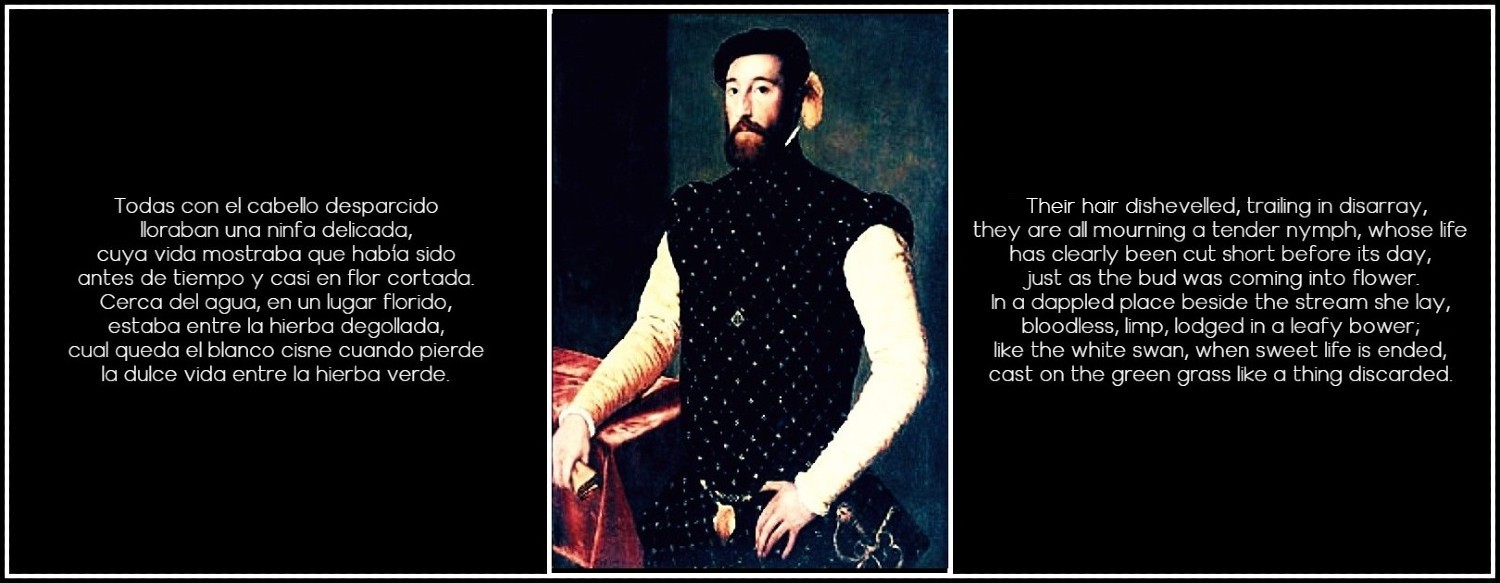

Garcilaso de la Vega, from Eclogue III, translated by John Dent-Young

Cisnes, los abanicos de vuestras alas frescas

den a las frentes pálidas sus caricias más puras

y alejen vuestras blancas figuras pintorescas

de nuestras mentes tristes las ideas obscuras.

Brumas septentrionales nos llenan de tristezas,

se mueren nuestras rosas, se agostan nuestras palmas,

casi no hay ilusiones para nuestras cabezas,

y somos los mendigos de nuestras pobres almas.

Nos predican la guerra con águilas feroces,

gerifaltes de antaño revienen a los puños,

mas no brillan las glorias de las antiguas hoces,

ni hay Rodrigos ni Jaimes, ni hay Alfonsos ni Nuños.

Faltos del alimento que dan las grandes cosas,

¿qué haremos los poetas sino buscar tus lagos?

A falta de laureles son muy dulces las rosas,

y a falta de victorias busquemos los halagos.

Swans, may the fans of your cool wings

give their purest caresses to pale brows

and may your white picturesque figures

drive dark ideas from our sad minds.

Septentrional mists fill us with sorrows,

our roses die off, our palm trees dwindle away,

there is scarcely a dream for our heads,

and we are beggars for our own poor souls.

They preach war to us with ferocious eagles,

gyrfalcons of bygone days return to the fists,

yet the glories of the old sickles do not shine,

there are no Rodrigos nor Jaimes, no Alfonsos nor Nuños.

At a loss for the vital spirit which great things give,

what will we poets do, but seek out your lakes?

For lack of laurels, roses are very sweet,

and for lack of victories, let’s seek out adulation

Francisco Jover y Casanova, Un guerrero del siglo XVI, 1884 | Felipe Ariosto, Alfonso IV, 1634 | Juan de Juanes, Caballero santiaguista, 1560

La América Española como la España entera

fija está en el Oriente de su fatal destino;

yo interrogo a la Esfinge que el porvenir espera

con la interrogación de tu cuello divino.

¿Seremos entregados a los bárbaros fieros?

¿Tantos millones de hombres hablaremos inglés?

¿Ya no hay nobles hidalgos ni bravos caballeros?

¿Callaremos ahora para llorar después?

He lanzado mi grito, Cisnes, entre vosotros,

que habéis sido los fieles en la desilusión,

mientras siento una fuga de americanos potros

y el estertor postrero de un caduco león

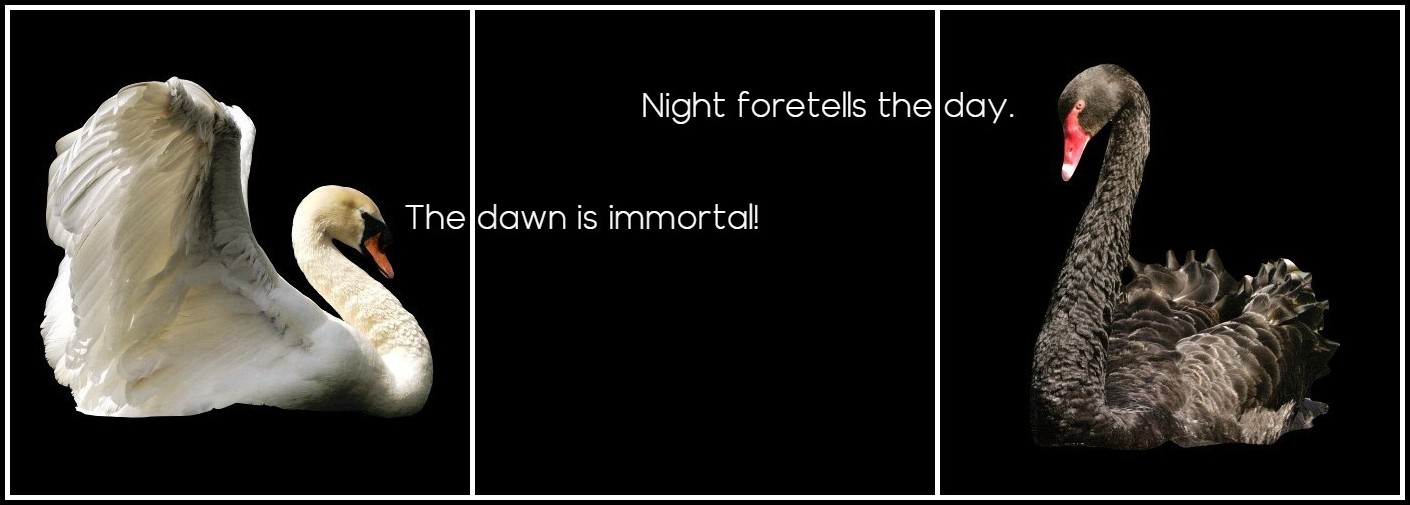

Y un Cisne negro dijo: ‘La noche anuncia el día’.

Y uno blanco: ‘¡La aurora es inmortal, la aurora

es inmortal!’ ¡Oh tierras de sol y de armonía,

aun guarda la Esperanza la caja de Pandora!

Spanish America, like Spain as a whole,

stands fixed in the East of its fatal destiny;

I question the Sphinx that awaits the future

with the question mark of your divine neck.

Will we be handed over to the wild barbarians?

So many millions of men, will we speak English?

Are there no worthy nobles nor manly knights anymore?

Will we be silent now only to weep later?

I have raised my cry, Swans, among you

who have been true believers despite disappointment,

while I hear a stampede of American colts

and the death rattle of a senile lion

And a black swan said: ‘Night foretells the day.’

And a white one: ‘The dawn is immortal! The dawn

is immortal!’ O lands of sun and of harmony,

Pandora’s box still contains Hope!

Rubén Darío, ‘Swans I’, tr. Will Derusha & Alberto Acereda | Swan photos: Malcolm Schuyl

III. LOS CISNES II

EN LA MUERTE DE RAFAEL NÚÑEZ

Rubén Darío

Que sais-je?

El pensador llegó a la barca negra;

y le vieron hundirse

en las brumas del lago del Misterio

los ojos de los Cisnes.

Su manto de poeta

reconocieron, los ilustres lises

y el laurel y la espina entremezclados

sobre la frente triste.

A lo lejos alzábanse los muros

de la ciudad teológica, en que vive

la sempiterna Paz. La negra barca

llegó a la ansiada costa, y el sublime

espíritu gozó la suma gracia;

y ¡oh Montaigne! Núñez vio la cruz erguirse,

y halló al pie de la sacra Vencedora

el helado cadáver de la Esfinge.

ON THE DEATH OF RAFAEL NÚÑEZ

Rubén Darío | W. Derusha & A. Acereda

Que sais-je?

The thinker arrived at the black ship;

and when he sank

into the mists of the lake of Mystery

the eyes of the Swans saw it.

His poet’s mantle

was recognized by the illustrious lilies

and the intermingled laurel and thorn

upon his sad brow.

Far away the walls

of the theological city arose, in which lives

sempiternal Peace. The black ship

came to the longed-for coast, and the sublime

spirit enjoyed the highest grace;

and—O Montaigne!—Núñez saw the cross erected,

and found at the foot of that sacred Vanquisher

the icy cadaver of the Sphinx.

French School, A Portrait of Montaigne, 16th c. (detail) | Museo Rafael Núñez, Rafael Núñez miniature, Cartagena (Colombia) (detail)

IV. EL CISNE

EL CISNE

Rubén Darío

Fue una hora divina para el género humano.

El Cisne antes cantaba sólo para morir.

Cuando se oyó el acento del Cisne wagneriano

fue en medio de una aurora, fue para revivir.

Sobre las tempestades del humano oceano

se oye el canto del Cisne; no se cesa de oír,

dominando el martillo del viejo Thor germano

o las trompas que cantan la espada de Argantir.

¡Oh Cisne! ¡Oh sacro pájaro! Si antes la blanca Helena

del huevo azul de Leda brotó de gracia llena,

siendo de la Hermosura la princesa inmortal,

bajo tus alas la nueva Poesía

concibe en una gloria de luz y de harmonía

la Helena eterna y pura que encarna el ideal.

THE SWAN

Rubén Darío | Lysander Kemp

It was a divine hour for the human race.

Before, the Swan sang only at its death.

But when the Wagnerian Swan began to sing,

there was a new dawning, and a new life.

The song of the Swan is heard above the storms

of the human sea; its aria never ceases;

it dominates the hammering of old Thor,

and the trumpets hailing the sword of Argentir.

Oh Swan! Oh sacred bird! If once white Helen,

immortal princess of Beauty’s realms, emerged

all grace from Leda’s sky-blue egg, so now,

beneath the white of your wings, the new Poetry,

here in a splendor of music and light, conceives

the pure, eternal Helen who is the Ideal.

Hendrick Goltzius, Helen of Troy, 1615 | Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Helen of Troy, 1863 | Gustave Moreau, Helen on the Trojan Ramparts, 1885 | Swan photo: Malcolm Schuyl

THREE BOOKS

Click or tap on the image to go to a description of the book

DERUSHA & ACEREDA, TRANSLATORS

Rubén Darío: Songs-Life-Hope

MALCOLM SCHUYL

The Swan: A Natural History

LYSANDER KEMP, TRANSLATOR

Selected Poems of Rubén Darío

Leda and the Swan: D.H. Lawrence, Rainer Maria Rilke, William Butler Yeats, Robert Graves