Giacomo Leopardi

Canto XXVI – Il pensiero dominante | Canto XXVII – Amore e morte | Canto XXVIII – A se stesso

CANTO XXVI – IL PENSIERO DOMINANTE

XXVI – IL PENSIERO DOMINANTE

Giacomo Leopardi

Dolcissimo, possente

Dominator di mia profonda mente;

Terribile, ma caro

Dono del ciel; consorte

5 Ai lúgubri miei giorni,

Pensier che innanzi a me sì spesso torni.

Di tua natura arcana

Chi non favella? il suo poter fra noi

Chi non sentì? Pur sempre

10 Che in dir gli effetti suoi

Le umane lingue il sentir propio sprona,

Par novo ad ascoltar ciò ch’ei ragiona.

Come solinga è fatta

La mente mia d’allora

15 Che tu quivi prendesti a far dimora!

Ratto d’intorno intorno al par del lampo

Gli altri pensieri miei

Tutti si dileguàr. Siccome torre

In solitario campo,

20 Tu stai solo, gigante, in mezzo a lei.

XXVI – THE DOMINANT IDEA

Giacomo Leopardi | Jonathan Galassi

Sweetest, potent

lord of my deep mind,

terrible but precious

gift of heaven, companion of

my grieving days,

idea that recurs to me so often.

Who doesn’t speak

of your mysterious nature?

Who hasn’t felt its power among us?

Yet, whenever their emotion

moves men to explain your influence,

what they have to say seems new to hear.

How unitary

has my mind become

since you took up residence.

As swift as lightning

every other thought of mine

vanished everywhere around.

Like a tower in an empty field,

you stand alone, gigantic, in my thinking.

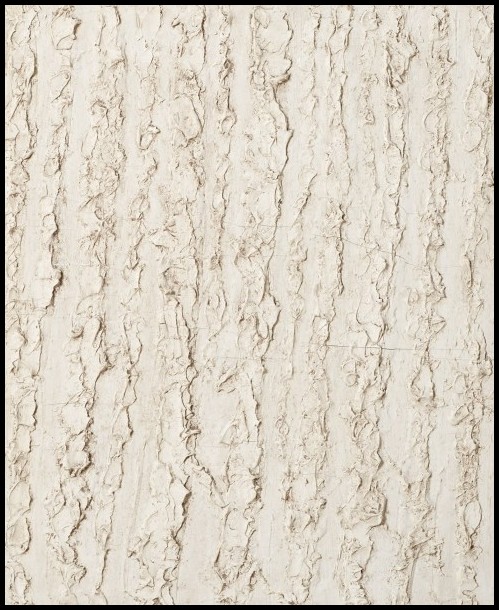

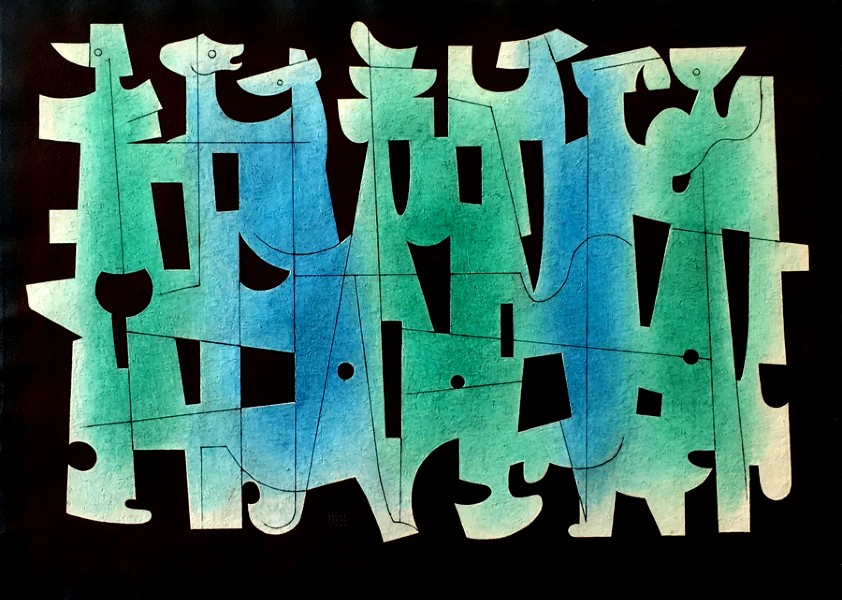

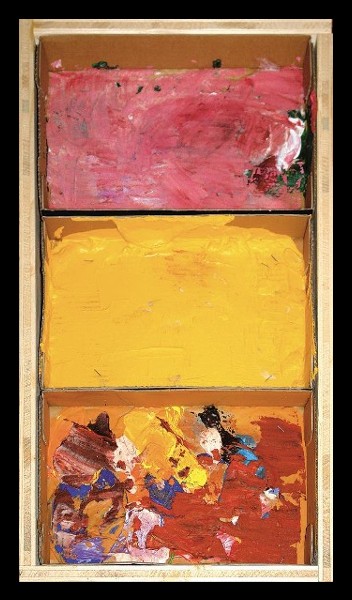

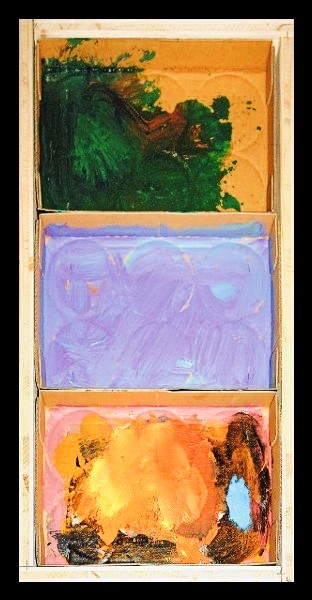

Enea Ferrari, Untitled, 1934 (detail)

Che divenute son, fuor di te solo,

Tutte l’opre terrene,

Tutta intera la vita al guardo mio!

Che intollerabil noia

25 Gli ozi, i commerci usati,

E di vano piacer la vana spene,

Allato a quella gioia,

Gioia celeste che da te mi viene!

Come da’ nudi sassi

30 Dello scabro Apennino

A un campo verde che lontan sorrida

Volge gli occhi bramoso il pellegrino;

Tal io dal secco ed aspro

Mondano conversar vogliosamente,

35 Quasi in lieto giardino, a te ritorno

E ristora i miei sensi il tuo soggiorno.

Quasi incredibil parmi

Che la vita infelice e il mondo sciocco

Già per gran tempo assai

40 Senza te sopportai;

Quasi intender non posso

Come d’altri desiri,

Fuor ch’a te somiglianti, altri sospiri.

What are they in my eyes now

next to you,

all earthly works, the whole of life!

What intolerable boredom

are idleness and small talk

and the empty hope for empty pleasure,

next to the joy, the heavenly joy

that comes to me from you!

As from the barren boulders

of the craggy Apennine

the pilgrim turns his eager eyes

toward a green field smiling in the distance,

so I from arid, acrid,

worldly chatter willingly

return to you as to a joyous garden,

and my stay with you restores my senses.

It seems almost incredible to me

that I endured unhappy life

and the idiotic world

so long without you.

I can barely understand

how another man can sigh

desiring something else that isn’t like you.

Enea Ferrari, Untitled, 1934 (detail)

Giammai d’allor che in pria

45 Questa vita che sia per prova intesi,

Timor di morte non mi strinse il petto.

Oggi mi pare un gioco

Quella che il mondo inetto,

Talor lodando, ognora abborre e trema

50 Necessitade estrema;

E se periglio appar, con un sorriso

Le sue minacce a contemplar m’affiso.

Sempre i codardi, e l’alme

Ingenerose, abbiette

55 Ebbi in dispregio. Or punge ogni atto indegno

Subito i sensi miei;

Move l’alma ogni esempio

Dell’umana viltà subito a sdegno.

Di questa età superba,

60 Che di vote speranze si nutrica,

Vaga di ciance, e di virtù nemica;

Stolta, che l’util chiede,

E inutile la vita

Quindi più sempre divenir non vede;

65 Maggior mi sento. A scherno

Ho gli umani giudizi; e il vario volgo

A’ bei pensieri infesto,

E degno tuo disprezzator, calpesto.

Before this I had no experience

that told me what this world is like,

fear of dying didn’t grip my heart.

Today extreme necessity,

which the inept world abhors and dreads,

though they sometimes praise it,

seems ridiculous.

And if danger comes, I steel myself

to contemplate its menace with a smile.

I’ve always had contempt

for cowards and ungenerous, mean spirits.

Now each unworthy act offends me instantly;

every type of human baseness

swiftly moves my spirit to disdain.

I disdain this prideful age,

which feeds itself on empty hopes,

in love with slogans, enemy of virtue,

this foolish age, which wants what’s useful

and so doesn’t see that life

is becoming constantly more useless.

I feel superior, and have contempt

for human judgment; and the motley crowd,

the enemies of beautiful ideas

who by nature denigrate you,

I trample on.

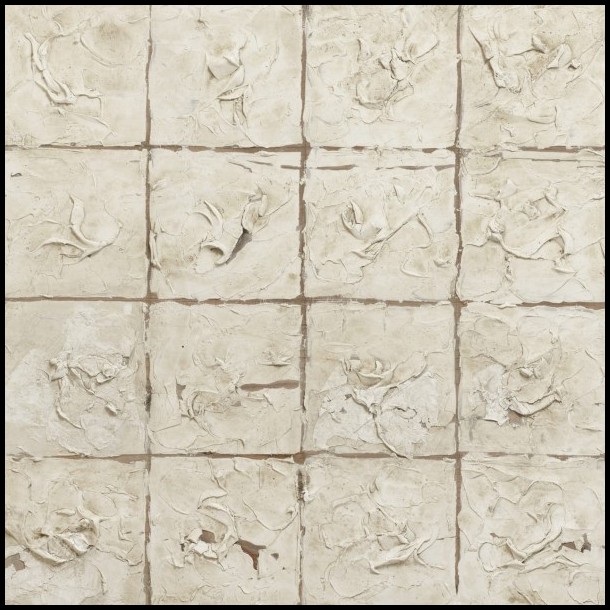

Enea Ferrari, Untitled, 1934

A quello onde tu movi,

70 Quale affetto non cede?

Anzi qual altro affetto

Se non quell’uno intra i mortali ha sede?

Avarizia, superbia, odio, disdegno,

Studio d’onor, di regno,

75 Che sono altro che voglie

Al paragon di lui? Solo un affetto

Vive tra noi: quest’uno,

Prepotente signore,

Dieder l’eterne leggi all’uman core.

80 Pregio non ha, non ha ragion la vita

Se non per lui, per lui ch’all’uomo è tutto;

Sola discolpa al fato,

Che noi mortali in terra

Pose a tanto patir senz’altro frutto;

85 Solo per cui talvolta,

Non alla gente stolta, al cor non vile

La vita della morte è più gentile.

Per còr le gioie tue, dolce pensiero,

Provar gli umani affanni,

90 E sostener molt’anni

Questa vita mortal, fu non indegno;

Ed ancor tornerei,

Così qual son de’ nostri mali esperto,

Verso un tal segno a incominciare il corso:

95 Che tra le sabbie e tra il vipereo morso,

Giammai finor sì stanco

Per lo mortal deserto

Non venni a te, che queste nostre pene

Vincer non mi paresse un tanto bene.

What love doesn’t give up pride of place

to the one from which you move?

Indeed, what other love holds sway

among mortal men but this?

Greed, pride, hatred, and disdain,

desire for honor and the crown—

what are these but vulgar hankerings

compared to it? One love alone

lives among us: the eternal laws

gave this one to the human heart,

as its all-commanding lord.

Life has no worth, no reason

except this, which is everything to man.

In itself, it exculpates

fate, which put us mortals here on earth

to suffer so much for no other reason.

Only because of this sometimes,

not for the foolish but the valiant heart,

can life be more beautiful than death.

To harvest your joys, sweet idea,

it was worth knowing human suffering,

worth enduring

this mortal life for all these years.

And I’d come back again,

I who am so expert in our pain,

to take the road again to such a goal.

For never till now did I journey to you

across the mortal desert,

among its sands and stinging vipers,

so worn out that vanquishing

these pains of ours did not seem a great good.

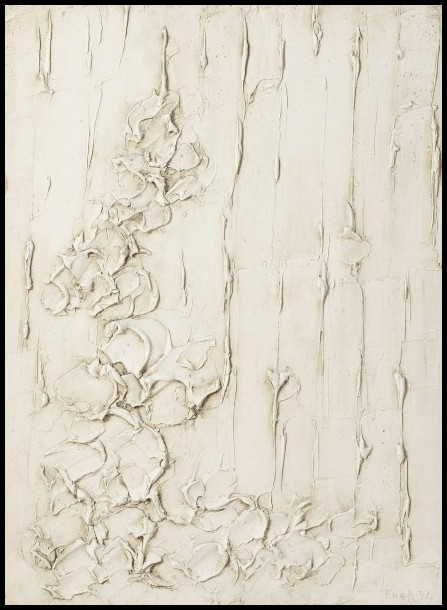

Enea Ferrari, Untitled, 1934

100 Che mondo mai, che nova

Immensità, che paradiso è quello

Là dove spesso il tuo stupendo incanto

Parmi innalzar! dov’io,

Sott’altra luce che l’usata errando,

105 Il mio terreno stato

E tutto quanto il ver pongo in obblio!

Tali son, credo, i sogni

Degl’immortali. Ahi finalmente un sogno

In molta parte onde s’abbella il vero

110 Sei tu, dolce pensiero;

Sogno e palese error. Ma di natura,

Infra i leggiadri errori,

Divina sei; perchè sì viva e forte,

Che incontro al ver tenacemente dura,

115 E spesso al ver s’adegua

Nè si dilegua pria, che in grembo a morte.

E tu per certo, o mio pensier, tu solo

Vitale ai giorni miei,

Cagion diletta d’infiniti affanni,

120 Meco sarai per morte a un tempo spento:

Ch’a vivi segni dentro l’alma io sento

Che in perpetuo signor dato mi sei.

Altri gentili inganni

Soleami il vero aspetto

125 Più sempre infievolir. Quanto più torno

A riveder colei

Della qual teco ragionando io vivo,

Cresce quel gran diletto,

Cresce quel gran delirio, ond’io respiro.

130 Angelica beltade!

Parmi ogni più bel volto, ovunque io miro,

Quasi una finta imago

Il tuo volto imitar. Tu sola fonte

D’ogni altra leggiadria,

135 Sola vera beltà parmi che sia.

What a world, what new immensity,

what a paradise it is

your overwhelming magic

often seems to raise me to! Where, wandering

in another light than the usual,

I forget my earthly nature

and everything that’s real!

Such are the immortals’ dreams, I think.

In the end, alas, in many ways,

you are a dream through which reality

becomes lovelier, sweet idea,

dream and patent error. But by nature,

among the pleasing errors you’re divine;

because you’re so alive and strong

that you hold up against the truth;

and often you do seem to be the truth,

and won’t fade till we’re in the lap of death.

But surely, O idea of mine,

you alone essential to my days,

beloved cause of endless suffering,

you’ll be undone by death along with me:

for from strong signals in my soul I feel

you’re given to me as my lord forever.

Other sweet illusions

would always weaken

the way that truth appeared to me.

But the more that I return

to see her whom I spend my life

telling you about, the more the great joy grows,

the more that great delirium grows

by which I breathe. Angelic beauty!

Every lovely face, wherever I look,

seems like an image made

in imitation of your face.

You, only source of every other grace,

you seem to me to be the one true beauty.

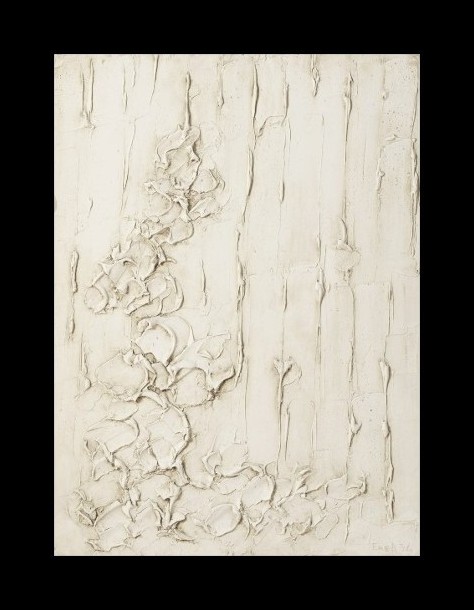

Enea Ferrari, Untitled, 1945

Da che ti vidi pria,

Di qual mia seria cura ultimo obbietto

Non fosti tu? quanto del giorno è scorso,

Ch’io di te non pensassi? ai sogni miei

140 La tua sovrana imago

Quante volte mancò? Bella qual sogno,

Angelica sembianza,

Nella terrena stanza,

Nell’alte vie dell’universo intero,

145 Che chiedo io mai, che spero

Altro che gli occhi tuoi veder più vago?

Altro più dolce aver che il tuo pensiero?

Since I first saw you,

what has the greatest object of my interest

been, but you? How much of the day

went by without my thinking of you?

How often was your sovereign image

missing from my dreams? Lovely as a dream,

angelic semblance,

in our earthly home or on the highways

of the entire universe,

what more can I ask, what can I hope for,

but to see your eyes more radiant,

what is sweeter than the thought of you?

Enea Ferrari, Untitled, 1945

ROBERTA CAUCHI-SANTORO ON ‘IL PENSIERO DOMINANTE’

Posted by kind permission of Roberta Cauchi-Santoro, Assistant Professor, Italian & French Studies, St Jerome’s University

From Roberta Cauchi-Santoro, Beyond the Suffering of Being: Desire in Giacomo Leopardi and Samuel Beckett (Firenze University Press, 2017)

In ‘Il Pensiero dominante’ the dominant but sweet fixation holds the poetic ‘I’ hostage (lines 1-2). This fixation could be compared to an unfulfilled desire for the Other which, however, has the power to elevate the spirit (lines 137-38). This Leopardian Other is as elusive and fictitious as the Lacanian one and its Stilnovistic ascendancy renders eloquent and adept what is crucial to Lacan: the fictitiousness of woman at the heart of courtly love poetry (lines 19-20). In this poem the palpable desire for life permeates the verses not in spite of but rather because of the desire for the Other (lines 80-1). The endlessness and irrepressible nature of this desire is also the poetic voice’s wish to find reconciliation with life and thus with itself. This desire is seen as the only justification (line 82) for human life defined as ‘to suffer so much for no other reason’ (line 84). The poetic voice’s quest for detachment from the cruel and base outside world is not merely a quest for self-sufficiency. Rather it is associated with the desire for the Other that also highlights the irreducible gap between the desire for recognition and the recognition of desire (lines 86-7). The painful desire for the Other is an illusion (line 111). This desire is, however, also a form of resistance (line 114).

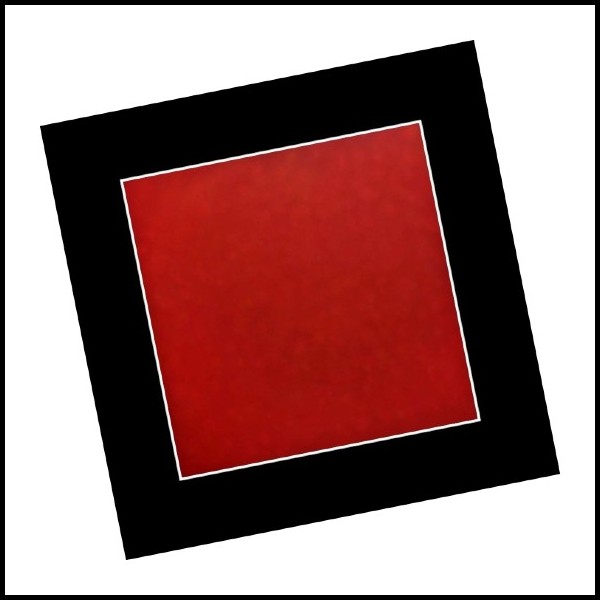

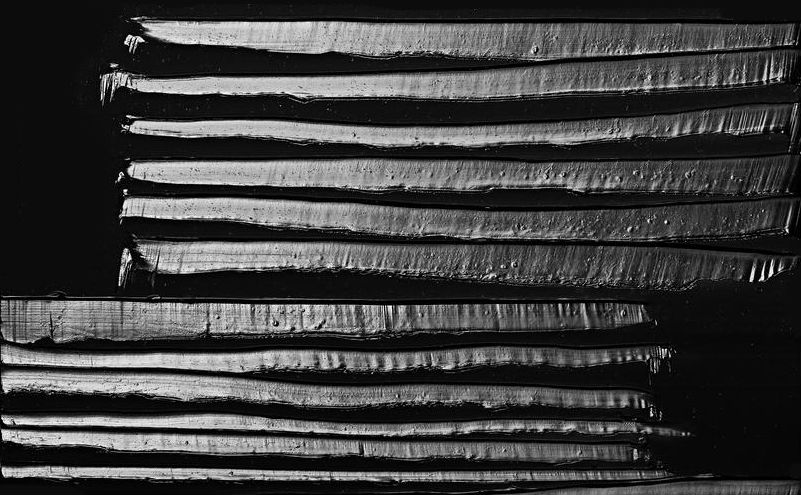

Pino Pinelli, Pittura, 1986

PAMELA WILLIAMS ON ‘IL PENSIERO DOMINANTE’

Pamela Williams, Department of Modern Languages, University of Hull (Retired)

From Pamela Williams, An Introduction to Leopardi’s Canti (Leicester: Troubadour Publishing, 2004)

The remarkable thing about Leopardi’s conception of love when it is inspired by a real woman is that it has the power to survive the knowledge that it is an illusion. In ‘Il pensiero dominante’, a real woman, generally identified as Fanny Targioni Tozzetti, has inspired a dream – the word ‘love’ itself is not mentioned – that has completely taken hold of the poet’s mind and yet he knows it is a dream. The poem is an emphatic statement of love’s power and exclusiveness: it alone can transform life into a paradise on earth; it is the only thing which gives meaning to life and makes life preferable to death; it is so powerful it can survive the knowledge that it is a dream.

Pino Pinelli, Pittura, 1986

In ‘Il pensiero dominante’ the poet is certain that the illusion of love will remain with him for the rest of his life, because every time he compares the illusion with the reality, that is with the real woman who has fired his imaginative dream, she inspires an even greater vision of happiness in his mind. At the end of the poem, the poet turns to address the angelic beauty of the reality; ‘angelic’ beauty, because with the beautiful illusion of love the world is transformed into a paradise on earth. In this poem more than any other in the Canti, the poet comes closest to experiencing the blessed state he describes right at the end of ‘Storia del genere umano’ when Love the divinity comes down from heaven to reside for a short while in the gentlest and tenderest hearts. Thus in ‘Il pensiero dominante’ the poet, knowing that love is not a reality, calls the thought of love divine among illusions.

Pino Pinelli, Pittura, 1986 + Pittura R, 1974

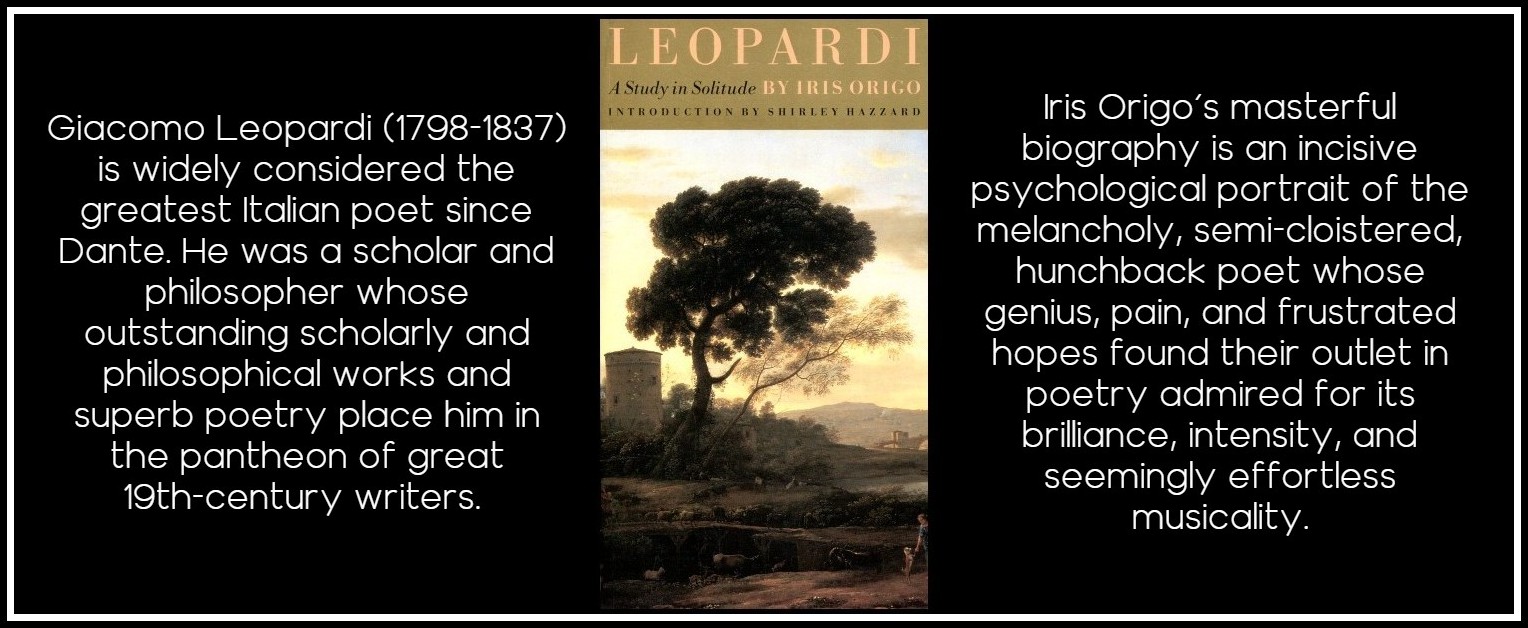

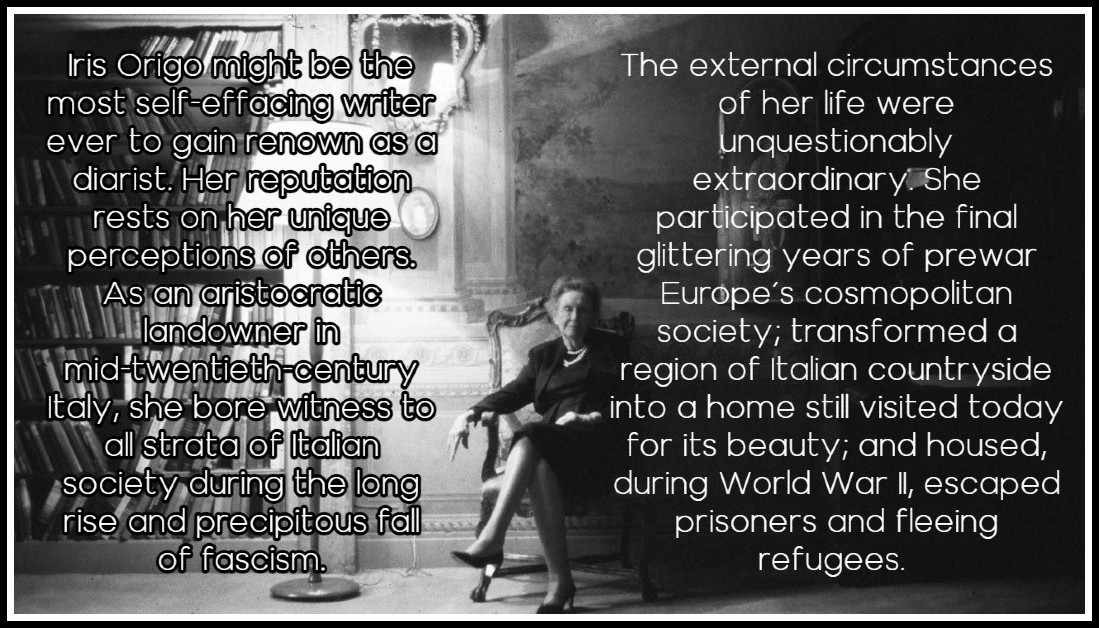

IRIS ORIGO ON ‘IL PENSIERO DOMINANTE’

Iris Origo is the author of ‘Leopardi: A Study in Solitude’

From Iris Origo, Leopardi: A Study in Solitude (NY: Books & Co./Helen Marx Books, 1999 [Hamish Hamilton 1953])

With every lost opportunity, every fancied snub, Leopardi’s first adolescent attitude to love hardened and became crystallized. What he feared was not merely a rebuff; perhaps his real dread was rather of success—and of finding, then, the deeper dissatisfaction he had always foreseen, the ‘unaccountable void that nothing can fill’. Geltrude Lazzari, Teresa Malvezzi, and now Fanny Targioni, what were they for him but shadows on a wall — paper silhouettes of his ‘heavenly original’, la donna che non si trova. Nowhere is this attitude more clearly revealed than in the poem which Leopardi wrote at the height of his love for Fanny Targioni, Il pensiero dominante. This poem is not addressed to his lady, but to his abstract idea of love—his obsessive ‘dominating thought’.

Pino Pinelli, Pittura R, 1974

He wrote, he thirsted during the dusty emptiness of social intercourse, as a wayfarer on a stony mountain seeks a green meadow. Only in his obsession could he feel himself like the gods; only then could he experience the sense of supreme power, of superhuman exaltation, that comes even to unrequited lovers; only then, fully realize the triviality of all the rest of life. Its dangers—even death, the ‘supreme necessity’—lost their power to alarm; all human opinions, ambitions, pride, became of small account. For more than a year Leopardi thus lived upon two planes: sometimes sitting, in his new blue suit, in the penumbra of Fanny Targioni’s drawing-room—a silent, incongruous figure among the somewhat flashy young men, the florid ladies, who assured the success of her evening parties; sometimes a god-like lover, dwelling alone in the pays des chimères.

Pino Pinelli, Pittura R, 1974

CANTO XXVII – AMORE E MORTE

XXVII – AMORE E MORTE

Giacomo Leopardi

Muor giovane colui ch’al cielo è caro.

Menandro

Fratelli, a un tempo stesso, Amore e Morte

Ingenerò la sorte.

Cose quaggiù sì belle

Altre il mondo non ha, non han le stelle.

Nasce dall’uno il bene,

5 Nasce il piacer maggiore

Che per lo mar dell’essere si trova;

L’altra ogni gran dolore,

Ogni gran male annulla.

10 Bellissima fanciulla,

Dolce a veder, non quale

La si dipinge la codarda gente,

Gode il fanciullo Amore

Accompagnar sovente;

15 E sorvolano insiem la via mortale,

Primi conforti d’ogni saggio core.

Nè cor fu mai più saggio

Che percosso d’amor, nè mai più forte

Sprezzò l’infausta vita,

20 Nè per altro signore

Come per questo a perigliar fu pronto

Ch’ove tu porgi aita,

Amor, nasce il coraggio,

O si ridesta; e sapiente in opre,

25 Non in pensiero invan, siccome suole,

Divien l’umana prole.

XXVII – LOVE AND DEATH

Giacomo Leopardi | Jonathan Galassi

He whom the gods love dies young.

Menander

Fate gave birth at one and the same time

to two siblings, Love and Death.

No other thing as fair

exists down here, or in the stars above.

Good is born of one,

the greatest pleasure

to be found upon the sea of being.

The other puts an end to all great sorrow,

each worst wrong.

Often Love, the little boy, is pleased

to be the playmate of the beauteous girl

who is delightful to behold,

not the way the craven crowd portrays her.

And they fly together

above the mortal highway,

the first comforts of all knowing hearts.

Nor was heart ever wiser

than when struck with love;

never did it disdain unlucky life

more powerfully, nor was prepared to suffer

danger for any other lord:

for when you lend your hand, Love,

courage is born

or born again, and human beings

turn wise in action,

not in empty thought, as is their wont.

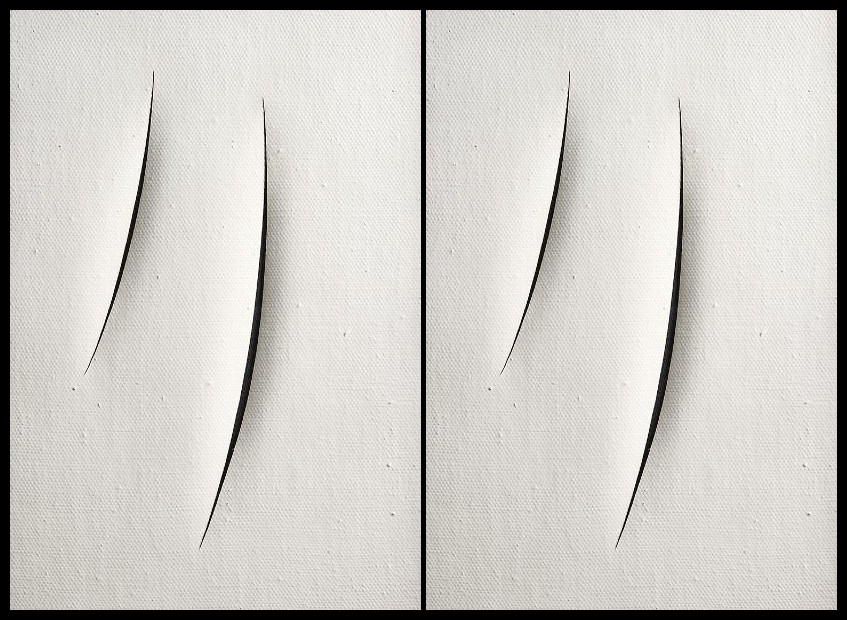

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, 1961-62

Quando novellamente

Nasce nel cor profondo

Un amoroso affetto,

30 Languido e stanco insiem con esso in petto

Un desiderio di morir si sente:

Come, non so: ma tale

D’amor vero e possente è il primo effetto.

Forse gli occhi spaura

35 Allor questo deserto: a se la terra

Forse il mortale inabitabil fatta

Vede omai senza quella

Nova, sola, infinita

Felicità che il suo pensier figura:

40 Ma per cagion di lei grave procella

Presentendo in suo cor, brama quiete,

Brama raccorsi in porto

Dinanzi al fier disio,

Che già, rugghiando, intorno intorno oscura.

45 Poi, quando tutto avvolge

La formidabil possa,

E fulmina nel cor l’invitta cura,

Quante volte implorata

Con desiderio intenso,

50 Morte, sei tu dall’affannoso amante!

Quante la sera, e quante

Abbandonando all’alba il corpo stanco,

Se beato chiamò s’indi giammai

Non rilevasse il fianco,

55 Nè tornasse a veder l’amara luce!

When a loving feeling

is newborn deep within the heart,

a languid and exhausted

wish to die arrives

at the same time,

I don’t know why; but this

is the first effect of true and potent love.

Perhaps this desert terrifies the eyes then,

or the mortal

finds earth is unlivable

without this new, unique, unending

happiness his mind conceives.

But sensing an ungovernable storm

brewing in his heart because of it,

he yearns for calm,

he yearns to come to port

before his wild desire,

already roaring, turning the world dark.

Then when the terrifying power

envelops everything,

and undefeated fear

strikes lightning in the heart,

Death, how often are you called upon

with keen desire by the suffering lover!

How often in the evening,

how often nodding off at dawn exhausted,

would he say he was blessed

if he never had to move his bones again

or return to see the bitter light!

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, 1961

E spesso al suon della funebre squilla,

Al canto che conduce

La gente morta al sempiterno obblio,

Con più sospiri ardenti

60 Dall’imo petto invidiò colui

Che tra gli spenti ad abitar sen giva.

Fin la negletta plebe,

L’uom della villa, ignaro

D’ogni virtù che da saper deriva,

65 Fin la donzella timidetta e schiva,

Che già di morte al nome

Sentì rizzar le chiome,

Osa alla tomba, alle funeree bende

Fermar lo sguardo di costanza pieno,

70 Osa ferro e veleno

Meditar lungamente,

E nell’indotta mente

La gentilezza del morir comprende.

Tanto alla morte inclina

75 D’amor la disciplina. Anco sovente,

A tal venuto il gran travaglio interno

Che sostener nol può forza mortale,

O cede il corpo frale

Ai terribili moti, e in questa forma

80 Pel fraterno poter Morte prevale;

O così sprona Amor là nel profondo,

Che da se stessi il villanello ignaro,

La tenera donzella

Con la man violenta

85 Pongon le membra giovanili in terra.

Ride ai lor casi il mondo,

A cui pace e vecchiezza il ciel consenta.

And often at the sound of funeral bells,

the singing that accompanies the dead

to their perpetual oblivion,

with many ardent sighs,

deep in his heart he envied him

who was going to stay with the dead.

Even simple people,

peasants, ignorant

of all the virtues that derive from knowledge,

even the timid, bashful girl

who feels her hair stand on end

at the very name of death,

dares to stare unflinchingly

at the tomb and widow’s weeds,

dares to meditate at length

on iron and poison,

and in her uneducated mind

knows death’s nobility.

So the law of love

inclines toward death.

And often the war within them is so great

that humans lack the power to resist it.

Either the frail body

surrenders to its awful turbulence,

and Death prevails through her sibling’s power,

or else Love wounds so deeply

that on their own the ignorant

farmer or the tender girl

bring their own young bodies

down by violence.

The world, which heaven guarantees

peace and old age, derides their fate.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, 1961-62

Ai fervidi, ai felici,

Agli animosi ingegni

90 L’uno o l’altro di voi conceda il fato,

Dolci signori, amici

All’umana famiglia,

Al cui poter nessun poter somiglia

Nell’immenso universo, e non l’avanza,

95 Se non quella del fato, altra possanza.

E tu, cui già dal cominciar degli anni

Sempre onorata invoco,

Bella Morte, pietosa

Tu sola al mondo dei terreni affanni,

100 Se celebrata mai

Fosti da me, s’al tuo divino stato

L’onte del volgo ingrato

Ricompensar tentai,

Non tardar più, t’inchina

105 A disusati preghi,

Chiudi alla luce omai

Questi occhi tristi, o dell’età reina.

May destiny grant

to fervent, glad, courageous minds

one or the other of you,

gentle lords,

the human family’s friends,

whose power no power

in the enormous universe can match,

and whom no might surpasses, except fate’s.

And you, whom from my earliest years

I’ve always honored,

lovely Death, you only in the world

pitying of earthly suffering,

if ever you were praised by me,

if ever I attempted

to answer the disdain

of the ungrateful crowd,

delay no longer,

answer these uncommon prayers,

shut these sad eyes now on the light,

O queen of time.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, 1960

Me certo troverai, qual si sia l’ora

Che tu le penne al mio pregar dispieghi,

110 Erta la fronte, armato,

E renitente al fato,

La man che flagellando si colora

Nel mio sangue innocente

Non ricolmar di lode,

115 Non benedir, com’usa

Per antica viltà l’umana gente;

Ogni vana speranza onde consola

Se coi fanciulli il mondo,

Ogni conforto stolto

120 Gittar da me; null’altro in alcun tempo

Sperar, se non te sola;

Solo aspettar sereno

Quel dì ch’io pieghi addormentato il volto

Nel tuo virgineo seno.

Surely you’ll find me, at whatever hour

you spread your wings in answer to my prayers,

head held high,

armed, and resisting fate.

Don’t weigh down with praise

the hand that, whipping me,

is colored with my blameless blood;

don’t glorify it as man does,

out of age-old cowardice.

Toss away from me

every vain desire with which the world

childishly consoles itself,

all foolish comfort. Let me not hope for anything

at any time but you alone;

may I simply wait serenely for

the day I’ll lay my sleeping face

on your virgin breast.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, 1960-63

ROBERTA CAUCHI-SANTORO ON ‘AMORE E MORTE’

Posted by kind permission of Roberta Cauchi-Santoro, Assistant Professor, Italian & French Studies, St Jerome’s University

From Roberta Cauchi-Santoro, Beyond the Suffering of Being: Desire in Giacomo Leopardi and Samuel Beckett (Firenze University Press, 2017)

In ‘Amore e morte,’ the poetic voice presents the desire for love at a juncture with desire for death, both considered in this poem as the most desirable aspects of human life (lines 1-4). The rich fervour of life can also be seen through the desire for death, just as in ‘Dialogo d’Ercole e di Atlante’ the rich fervour of life on earth is accentuated by being reduced to mechanical actions. The paradoxical striving for two mutually exclusive goals recalls once more Lacan’s statement: ‘Man’s very desire is constituted […] under the sign of mediation: it is the desire to have one’s desire recognized. Its object is a desire, that of other people, in the sense that man has no object that is constituted for his desire without some mediation’ (Écrits 148). Desire for life, the Leopardian ‘a loving feeling’ (line 29), and desire for death, the ‘fierce desire’ (line 43), are two sides of the same coin as Freud later argues in Beyond the Pleasure Principle and as Lacan subsequently elaborates in his distinction between demand and desire. The desire for death in this poem almost prefigures the Lacanian moi’s desire for fusion manifesting itself in an underlying death wish that remains unfulfilled. Desire for death in ‘Amore e morte’ not only reflects the futile quest that is the nature of human desire but it is also elevated to become an act of magnanimity: ‘death’s gentleness’ (line 73).

Carlos Mérida, Egeo Rey, 1979

PAMELA WILLIAMS ON ‘AMORE E MORTE’

Pamela Williams, Department of Modern Languages, University of Hull (Retired)

From Pamela Williams, An Introduction to Leopardi’s Canti (Leicester: Troubadour Publishing, 2004)

Amore e morte is an appropriate poem to follow Il pensiero dominante because Leopardi considers a desire for death the first effect of true and powerful love, and in love (according to his extraordinary conception of love), he himself desires only to die. In terms of Leopardi’s perception of human life, love and death are the most beautiful things the world has to offer. In Leopardi’s terms lovers become wise because love makes them see life for what it really is. People who experience true and powerful love desire death because they feel they cannot live in a world without the vision of happiness which their love has inspired. It seems that the sheer intensity of what they know to be insatiable longing makes them desire death and gives them the courage to die. In the poem, with the vision of happiness love inspires, the courage to kill oneself is reborn. The poet is convinced that people who experience true and powerful love understand the sweetness of death; even the man who did not know the truth before and therefore did not despise life, even the shy young girl who was afraid to die. At the end of stanza 2 the poet taunts the world who laughs at those who kill themselves for love’s sake. In the context of Amore e morte, ‘peace’ and ‘old age’ are actually the worst things that can be wished on anyone because they are the opposite of ‘love’ and ‘death’ respectively. He is not out of love at the end of the poem; his weary desire to fall asleep in the bosom of death is the direct consequence of the vision of happiness love inspires.

Carlos Mérida, Tierra Humeda, 1966

IRIS ORIGO ON ‘AMORE E MORTE’

Iris Origo is the author of ‘Leopardi: A Study in Solitude’

From Iris Origo, Leopardi: A Study in Solitude (NY: Books & Co./Helen Marx Books, 1999 [Hamish Hamilton 1953])

Love and Death appear as the twin protagonists of a Leopardian myth, in which Love stands for the creative principle of life, Death for the powers of destruction; but at the end of the poem the figure of Death—ardently invoked by the poet—has suffered a shadowy identification with the beloved woman herself; and thus, in seeking death, the lover also finds fulfillment.

Carlos Mérida, La Rosa de los Vientos, 1965

CANTO XXVIII – A SE STESSO

XXVIII – A SE STESSO

Giacomo Leopardi

Or poserai per sempre,

Stanco mio cor. Perì l’inganno estremo,

Ch’eterno io mi credei. Perì. Ben sento,

In noi di cari inganni,

5 Non che la speme, il desiderio è spento.

Posa per sempre. Assai

Palpitasti. Non val cosa nessuna

I moti tuoi, né di sospiri è degna

La terra. Amaro e noia

10 La vita, altro mai nulla; e fango è il mondo.

T’acqueta omai. Dispera

L’ultima volta. Al gener nostro il fato

Non donò che il morire. Omai disprezza

Te, la natura, il brutto

15 Poter che, ascoso, a comun danno impera,

E l’infinita vanità del tutto.

XXVIII – TO HIMSELF

Giacomo Leopardi | Jonathan Galassi

Now you’ll rest forever,

worn-out heart. The ultimate illusion

that I thought was eternal died. It died.

I see not just the hope

but the desire for loved illusions

is done for us. Be still forever.

You have beaten long enough.

Nothing deserves your throbbing, nor is earth

worth sighing over. Life is merely

bitterness and boredom, and the world is filth.

Now be calm. Despair for the last time.

Death is the one thing

fate gave our kind.

Disdain yourself now, nature, the brute

hidden power that rules to common harm,

and the boundless vanity of all.

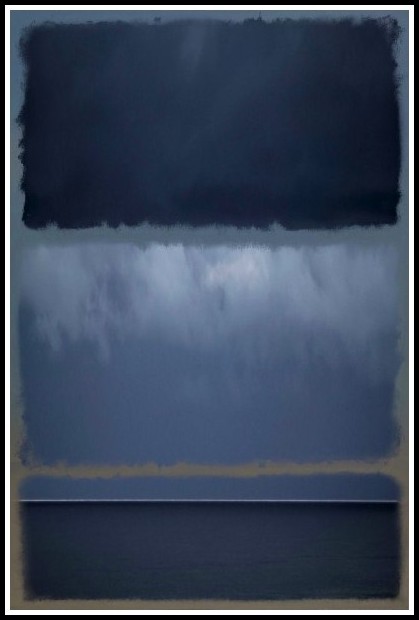

Richard Ehrlich, Homage to Rothko 14, 2016

ROBERTA CAUCHI-SANTORO ON ‘A SE STESSO’

Posted by kind permission of Roberta Cauchi-Santoro, Assistant Professor, Italian & French Studies, St Jerome’s University

From Roberta Cauchi-Santoro, Beyond the Suffering of Being: Desire in Giacomo Leopardi and Samuel Beckett (Firenze University Press, 2017)

In ‘A se stesso’, the cleaved ‘I’ is even more pronounced, and in that split the poetic voice is, in a more accentuated manner than in the above-mentioned poems, in conflict. As Perella points out, nothing in the Canti is as starkly desolate as the epitaphic ‘A se stesso,’ in which Leopardi, announcing the death of hope and desire, commands his heart to stop beating. In this poem the poetic ‘I’ is an Other to itself, and in this sense is Lacanian through and through. In this conflict, which echoes the Hegelian master-slave dialectic, lies the poetic ‘I’’s subjection and attempt to resume control over the Other. The poetic ‘I’, however, both desires and recoils from this Other, who in this case is the repository of sentiment, a source of acute pain and suffering (lines 2-3). The poetic ‘I’’s utterances, which oscillate between ‘io’ (‘I’) and ‘noi’ (‘we’), attempt to eliminate the Other as it laments a desire that is no longer. The presence of words here, as in Freud’s fort/da game, is inextricably bound up with an absence (lines 7-8). Words are uttered forcefully but seem powerless in the face of an infinitely malevolent universe. In ‘A se stesso’ the effort of the poetic voice to come to terms with its own utterances, and consequently its own suffering, can be equated, from a Lacanian perspective, to an apparently futile desire for the Other.

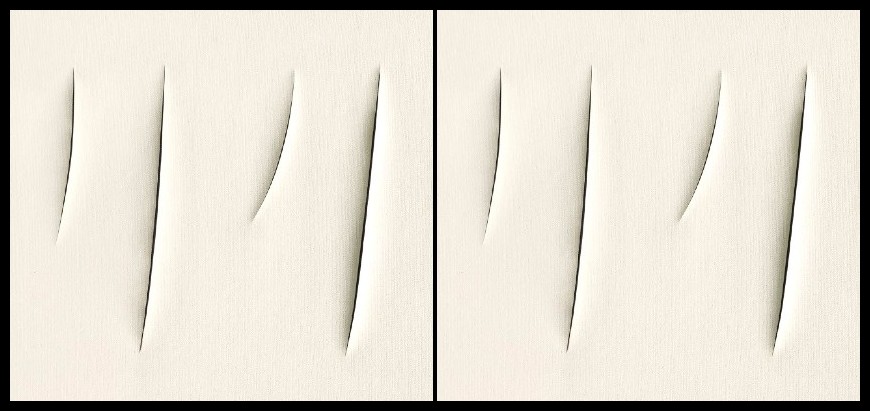

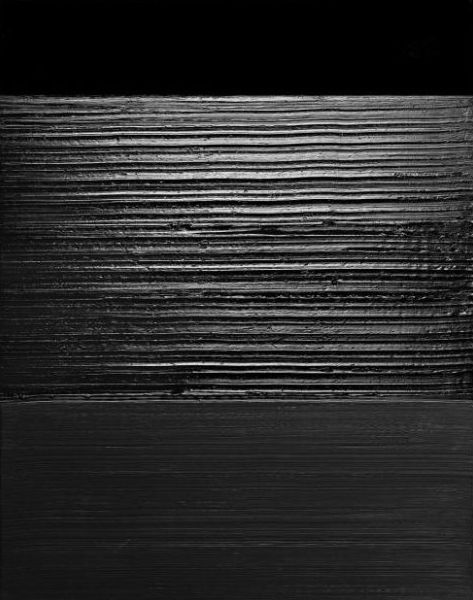

Pierre Soulages, 2013

From the outset the poetic ‘I’ immediately attempts to assume control over the Other in an urge to acquiesce suffering (lines 1-2, 6-7). But the soothing, hushed tones blend in with the harshness of a poetic voice that has turned dour and cynical in an effort to totally eliminate the Other as revealed through its repetition of absolute words: ‘per sempre’ [‘forever’; line 1], ‘estremo’ [‘ultimate’; line 2], ‘per sempre’ [‘forever’; line 6], ‘mai’ [‘never’; line 10], ‘l’ultimo’ [‘last’; line 12], and ‘l’infinita’ [‘boundless’; line 16]. The mercilessness of the poetic ‘I’’s predicament is clear enough (lines 9-10). Thus, on the one hand, the poetic ‘I’ unremittingly fails to detach itself from life (lines 13-16); on the other hand, the mind is bound to move in a repetitious cycle that keeps revisiting ‘l’inganno estremo’ [‘the ultimate illusion’]; (line 2). Once more, this two-way movement corresponds to Lacan’s expression that not to want to desire and to desire are the same thing. Desire is insatiable; desire is an act of seeking without finding that both underlines and undermines it. The ‘inganno estremo’ will never cease haunting.

Pierre Soulages, 2012

ROBERTA CAUCHI-SANTORO: TWO BOOKS

CLICK OR TAP THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

ROBERTA CAUCHI-SANTORO

Beyond the Suffering of Being

R. CAUCHI-SANTORO & C. BARCHIESI

Ferrante Unframed

PAMELA WILLIAMS ON ‘A SE STESSO’

Pamela Williams, Department of Modern Languages, University of Hull (Retired)

From Pamela Williams, An Introduction to Leopardi’s Canti (Leicester: Troubadour Publishing, 2004)

In ‘A se stesso’, the illusion has disappeared for ever. Given the value of illusions in Leopardi’s perception of human life, given that love is the last illusion to survive, we cannot wonder that its loss occasions the despair so powerfully conveyed in this short poem. Leopardi had used a past definite of ‘perire’ before to convey irrevocability in the Canti but never with so great effect as in lines 1-3. The starkness of ‘A se stesso’ has tremendous impact. In sixteen lines there are twelve sentences with only two subordinate clauses, lines 3 and 15, and two coordinates, lines 8 and 10. The imperatives addressed to his heart, the sound repetitions, the oxytones, the nouns denoting quality, all hammer out the finality of the poet’s loss. The pain that he had feared had come—and when it passed away, it took with it what was most vital in him. After the destruction of this last ‘illusion’, Leopardi lived on for four more years, but he wrote no more love-poems, and he brought to an end the great day-book in which, for seven years, he had jotted down all his thoughts. Some vital spring was broken—‘not hope alone, but all desire had fled’. Once again Leopardi lays before us ‘the hidden and mysterious cruelty of human destiny’, but this time he employs no argument, points no moral: we hear something simpler and more moving: a human cry of pain.

Pierre Soulages, 2013

IRIS ORIGO ON ‘A SE STESSO’

Iris Origo is the author of ‘Leopardi: A Study in Solitude’

From Iris Origo, Leopardi: A Study in Solitude (NY: Books & Co./Helen Marx Books, 1999 [Hamish Hamilton 1953])

‘A se stesso’ refers to the final break with Fanny Targioni Tozzetti—loneliness, humiliation, sense of betrayal, self-mistrust—the profound weariness that engulfed him.

Pierre Soulages, 2013

GIACOMO LEOPARDI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Seven Chapter 2

Jagged stalks, dusted with snow, recede to a row of bare trees marking the horizon: On both sides of the highway, stubble fields stretch out.

̶ Do you know Leopardi, Sprague?

̶ Yes. Do you?

̶ No.

̶ He’s the brother I never had. I feel very close to him.

̶ Really? Tell me about him.

Cornelius Kolig, Palettenkasten, 2003

And thus I came to speak of my beloved Giacomo, of his early understanding that life is nothing but a process of losing: ‘The only people who truly live until their death are those who remain children all their lives.’ I spoke of his pitiless mother, haunted by a sense of sin, incapable of touching her children. I spoke of the boy bent over his books, freezing in his father’s library. Homer and Virgil, Dante and Tasso, Seneca and Cicero: These were Giacomo’s intimates. I spoke of his overwhelming longing for the tenderness of a woman, a tenderness he would never know. ‘Intelligent enough to appreciate his genius, vulnerable enough to be kind’: He never met such a woman. His scoliosis, the hump on his back, was but the visible sign, I asserted, that he’d been marked out for sorrow. And thus he was hurt into poetry. As you warmed to my portrait, I spoke of Leopardi’s ethics of lucidity, his refusal of abstraction, his recognition of the individual as an absolute. His poetry, I explained, in restoring presence to things, creates a silence in which memory can speak. Suffering, mourning and solitude—yes, but in a graceful moon on a quiet night there is the promise of a woman and a shared life: Leopardi is the poet of tenderness.

̶ The brother you never had, hey?

Your eyes shine and I see mine in them: I want to wrap my arms around you, I want to press your body to mine. Or just fall down at your feet.

Cornelius Kolig, Palettenkasten, 2003

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

IRIS ORIGO: LEOPARDI, A STUDY IN SOLITUDE

IRIS ORIGO, ‘LEOPARDI: A STUDY IN SOLITUDE’

A. Ferrazzi, ‘Giacomo Leopardi’, 1820

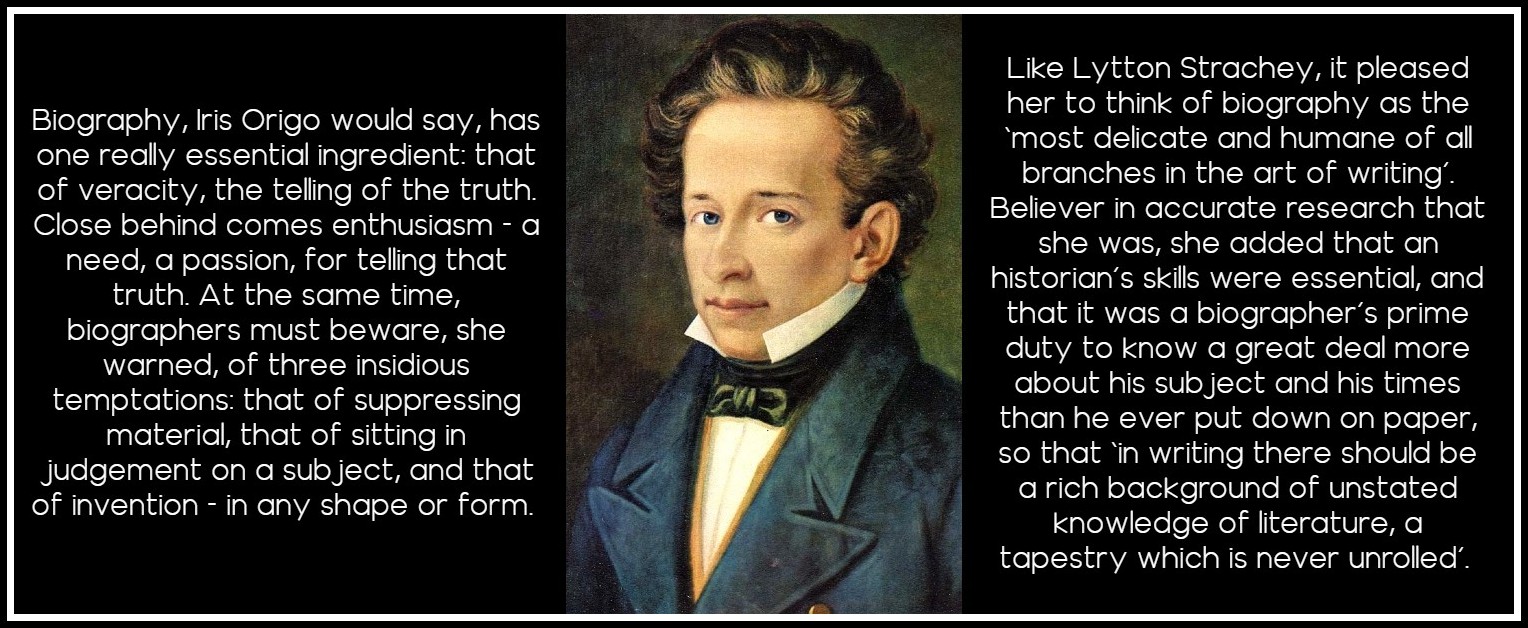

CAROLINE MOOREHEAD, ‘IRIS ORIGO: MARCHESA OF VAL D’ORCIA’ (LONDON: ALLISON & BUSBY, 2000)

Domenico Morelli, ‘Giacomo Leopardi’, 1845

CAROLINE MOOREHEAD, ‘IRIS ORIGO: MARCHESA OF VAL D’ORCIA’ (LONDON: ALLISON & BUSBY, 2000)

LAUREN KANE, ‘FEMINIZE YOUR CANON: IRIS ORIGO’ (‘THE PARIS REVIEW’, 24 OCT 2019)

RIMBAUD I (Le Dormeur du val | Chanson de la plus haute tour | Veillées I)