Twelfth Night

SHAKESPEARE – ‘TWELFTH NIGHT’: DESTABILIZING GENDER AND SEXUALITY

Carol Thomas Neely

All images from Trevor Nunn’s film of Twelfth Night, 1996.

From Carol Thomas Neely, Distracted Subjects: Madness and Gender in Shakespeare and Early Modern Culture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004) pp. 115-121. Text edited for the sake of concision.

The subtitle of Twelfth Night—‘What You Will’—and its three symbolically named, willful characters—Viola, Olivia and Malvolio (their names all partial anagrams of ‘volition’)—designate the play a site of unruly desires. Erotic and gender irregularity are remarkably untrammeled in Twelfth Night. Cesario’s role and the shifting triangular identifications of lovers tease apart gender and eroticism so that status, not gender, becomes the primary modality that incites and circulates unruly desires. Erotic desire is a function of age, status (economic and social), and body type more than of gendered objects. Because Viola/Cesario, the cross-dressed character at the center of the triangles, remains in disguise throughout virtually the entire play, her ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’ are simultaneous and inseparable, not polarized.

Imogen Stubbs as Viola/Cesario

Viola/Cesario

This character’s gender and erotic identifications, roles, and styles are nuanced but sustained. Viola/Cesario identifies as a woman in love in brief soliloquies, but plays the role of a boy in company; her ‘masculine’ gender style oscillates between wistfully boyish (with Orsino) and cheekily adolescent (with most others)—between passive resignation and assertive wit. These qualities are as apparent out of disguise as in it. Her/ his erotic identification is female, her/his erotic (and bi-gendered) role is service, and his/her erotic style is to express desires covertly and elicit them from others through specularity. Hence she/he can elicit by mirroring (in cross-gendered fashion) different modalities of desire from differently gendered lovers/love objects whom he/she similarly serves self-interestedly. The servant’s supposedly subordinate position mobilizes erotic power.

Cesario/Viola uses her own ‘contemned’ desires to specularize those of others as she travels back and forth between the two households. She engenders Olivia’s desires (for him/her) by anticipating their urgency in the promise to act and speak—to ‘Make me a willow cabin at your gate… Write loyal cantons of contemnèd love… Hallo your name to the reverberate hills’. Here Cesario ventriloquizes Orsino’s romantic desires for Olivia in a note that enables Viola to voice her own more demanding ones for Orsino. These reverberations spur Olivia’s desires as she responds immediately, ‘You might do much. What is your parentage?’. Later, Viola/Cesario mirrors and elicits the desires that underlie Orsino’s fetishistic love for Olivia by speaking her own for him, relayed through those of an imaginary sister who dies of erotic melancholy: ‘She pined in thought; and, with a green and yellow melancholy, she sat like Patience on a monument, smiling at grief’. This self-projection of standard erotic melancholy represents Orsino’s and her own frustration whereas the willow cabin builder represents Olivia’s and her initiative-taking. The effects of these two scenes are to release desires that are not definitively homosexual or heterosexual. Its relays are complex, its circulation endless, its field practically boundless.

Olivia/Ceasario with Helena Bonham Carter as Olivia

Olivia

Most characteristically, Cesario forcefully enacts Viola’s desire for erotic service. On first hearing of the Duke’s love for Olivia, her response is to ‘serve’ one or the other, and she becomes page to Orsino. Later, in act 3, Cesario is ‘votre serviteur’ to Andrew, vows ‘most humble service’ to Olivia, and is said to be ‘servant’ to the Count Orsino: ‘Your servant’s servant is your servant,’ quips Cesario/Viola. ‘Service’ here connotes a status, a bi-gendered role, and an erotic style, one that perhaps is an incentive to disguising and that the disguise facilitates. The reverberations of desire that Viola exudes and elicits undo polarized gender roles, represent permeable subjectivities, and loosen boundaries between homoerotic and heteroerotic desires.

Gendered object choice seems to play only a small part in Orsino’s and Olivia’s attachments as well. Their wealth, aristocratic status, and power as heads of households give both a similar habit of command and love for servants, although their erotic styles are differently expressed. Olivia likes to ‘command’ and is drawn to youthful subordinates of either gender, but not to the perhaps older and more socially powerful Malvolio and Orsino. Sir Toby tells Maria that Olivia won’t marry the Count because she has sworn not to ‘match above her degree, neither in estate, years, nor wit’. She admits Cesario/Viola to her only on learning that he is ‘Not yet old enough for a man nor young enough for a boy’. She is attracted to his poor, but gentlemanly state (‘Above my fortunes, yet my state is well’) and to attributes that are not gender specific: ‘Thy tongue, thy face, thy limbs, actions, and spirit’. She ‘catches the plague’ conventionally when she feels ‘this youth’s perfections with an invisible and subtle stealth to creep in at mine eyes’. Since Sebastian has the same adolescent attributes, the same face and limbs, more pliability, and less money, he is an equally apt object of Olivia’s desires.

Olivia and Viola/Cesario with Toby Stephens as Orsino

Steven Mackintosh as Sebastian, with Olivia

Sebastian, like Olivia, seems more turned on by age and economic markers than by gendered attributes. What he wants is to be kept, and he is perhaps willing to sleep with anyone who will do so. Like his twin, Viola, he finds protective possessiveness in older men and in rich women especially attractive. So he easily slides from dependence on Antonio’s power and purse to dependence on Olivia, who has more rank and money and is equally dominating. She runs her household and Sebastian with a firm hand. ‘Would thou’dst be ruled by me!’ Olivia demands. ‘Madam, I will,’ replies Sebastian, combining volition with subordination. ‘O, say so, and so be,’ she replies, completing a traditional spousal that reverses prescribed gender hierarchies.

Orsino, even more than Olivia, likes giving orders to servants. In Viola/Cesario, Orsino is attracted to the same adolescent and subordinate qualities as Olivia is; indeed it is his awareness of the potential appeal of Cesario’s ‘youth’ to Olivia that triggers his own eroticized perception: ‘Diana’s lip is not more smooth and rubious; thy small pipe is as the maiden’s organ, shrill and sound, and all is semblative a woman’s part’. As my italics suggest, Orsino is attracted to Cesario because he is appealingly like a woman but not a woman—that is, not like imperious Olivia. Although the tender ‘part’ Cesario plays for and with Orsino is less witty than the one he plays for and with Olivia, it is equally obstinate and not necessarily more ‘feminine.’ He responds to his master’s and his mistress’s needs differently, just as he reverberates differently to each the shapes of their own desires. Her/his layered erotic and gendered style enables Olivia to desire a woman and Orsino to desire a man.

Orsino and Viola/Cesario

Olivia and Orsino

Orsino’s love for Olivia, in contrast to his intimate exchanges with Cesario, partakes of the fetishism and narcissism, the love for an idealized, unobtainable object that only men typically exhibit. His opening speeches document his absurd fixation on his own fantasies and his lack of interest in any contact with the disdainful Olivia. They also delineate all the symptoms of lovesickness that he fantasizes Olivia catching. Love fills his ‘liver, brain, and heart’, as it may hers. His ‘fancy’ is ‘full of shapes’; his ‘desires’ ‘pursue’ him; and the solitude and music, traditionally recommended as cures, only exacerbate them. Proud of his grandiose love, he argues that men’s capacity for love is greater than women’s—because women’s hearts are too small and their palates only, not their livers, are infected. He also claims they ‘lack retention’—both the genital capacity for love and the ability to remain constant—thus responding to an old debate about genital pleasure with a new argument for male psychosomatic capacity. But Viola, who earlier claimed that women’s ‘waxen hearts’ and ‘frailty’ make them more susceptible to love than men, articulates and acts out in the play, as does Olivia, the culture’s growing belief that women’s lovesickness is greater than men’s.

It is Antonio, however, who is the play’s most passionate, expressive, and constant lover; his beloved object, Sebastian, is unconventional only in his gender. Their intimacy is well established, and Antonio’s passion is equally romantic and erotic. His gender and erotic roles are complex. He is a sea captain and a pirate, a romantic hero who will brave anything for love, declaring his ‘devotion’ and ‘sanctity of love’ to his beloved’s ‘image’. But he also expresses his body’s demands: ‘My desire, more sharp than filèd steel, did spur me forth’. He is older and richer than Sebastian, yet he also begs to be his beloved’s ‘servant’—an erotic stance consonant with his lower status role. His scenes provoke relief through their directness and poignancy, a sharp contrast to the romantic fancy and triangular suggestiveness of adjacent parallel love scenes between others. Like Olivia, who is his replacement and whose erotic roles are comparable, he is represented sympathetically. He is baffled by confusing the identical twins but is not humiliated by either the characters or the play itself.

Nicholas Farrell as Antonio, with Sebastian

Antonio and Sebastian

At the play’s ending, his relationship with Sebastian (whatever its precise nature) must now be shared; but it is not decisively ended by the youth’s marriage, and Antonio is not excluded from the ending. After his first encounter with Olivia, Sebastian immediately seeks out Antonio: ‘His counsel now might do me golden service’. His exclamation, when they are reunited after his marriage, is passionate: ‘Antonio, oh my dear Antonio, how have the hours racked and tortured me since I have lost thee!’. Although Sebastian’s reunion with Antonio is displaced by his longer one with Viola, he exchanges no more words with Olivia after this—and has exchanged none as passionate as these. The ending leaves open the possibility that marriage and a homoerotic attachment can coexist in early modern culture.

The ‘specific anxiety about reproduction’ that some critics ‘hypothesize as a structuring principle’ for these comedies is virtually unacknowledged in them. Indeed in Twelfth Night it is absent altogether. There is no older generation, no emphasis on lineage, indeed no represented family or political order at all. Unlike the conclusions of a majority of Shakespeare’s comedies, including Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Merchant of Venice and As You Like It, Twelfth Night contains no concluding anticipation of reproduction or of the accompanying fear of cuckoldry. These are missing even from Feste’s final disillusioned song, which narrates a man’s progression through life—although his protagonist does ‘wive’. The lack of projection of a social order or of a reproductive or political future allows the circuits of desire to remain open at the ending. Twelfth Night’s irregular matches are further made acceptable—structurally, thematically, and ideologically—by the humiliation of Malvolio for desires that, like those of the others, are incited by status difference and social ambitions.

Orsino and Viola/Cesario

Orsino, Sebastian and Olivia

The marriages that the play anticipates or completes do not re-establish conventional erotic pairings or gender hierarchies or promise children. Instead the fluidity of desire and gender is reemphasized at the conclusion by the large residue of bi-gendered and bisexual subjectivity which remains. As we have seen, Sebastian remains loved by Antonio and Olivia and Viola and loves all three. Although Cesario is revealed as Viola, the twins share ‘one face, one voice, one habit’. Their many similarities of looks, desires and roles make their nominally different genders of scant importance. Orsino’s affections easily enlarge to embrace Viola along with Cesario. He effortlessly moves Viola into the place formerly held by Olivia as ‘Orsino’s mistress and his fancy’s queen’. At the same time he offers his ‘boy’ and ‘lamb’ his hand for service already tendered and continues to call him Cesario; s/he continues to ‘over swear’ the ‘sayings’ Cesario formerly swore. S/he remains in male dress and the retrieval of her ‘other (female) habits’ is deferred, as is her movement into a normative gender role. Like the Duke, Olivia is ‘betrothed both to a maid and man’. She likewise embraces her surrogate love object with equanimity since he has all the qualities she desired in Cesario and continues to be subordinate to her.

Olivia, still entirely in control, interrupts the unfolding ending to free Malvolio and assess blame. While waiting for his appearance, she occupies herself by arranging a double wedding:

My lord, so please you, these things further thought on,

To think me as well a sister as a wife,

One day shall crown th’alliance on’t, so please you,

Here at my house and at my proper cost.

Her offer to pay for Orsino’s marriage forces his hand—literally—for her words generate his explicit offer of marriage to Cesario and the giving of his hand: ‘Here is my hand; you shall from this time be your master’s mistress’. But Olivia concludes the line—‘A sister; you are she’—translating her affection for Viola/Cesario into a new configuration. Hence the play that begins in the household of Orsino ends at Olivia’s; she displaces the Duke as the primary authority figure in Illyria. Neither marriage is represented as conventionally gendered or even exclusively heterosexual, and bonds and pleasures other than marital ones explicitly persist and are acknowledged in the final scene.

Viola/Cesarion and Sebastian

Stanley Wells, Shakespeare, Sex, and Love

Carol Thomas Neely, Distracted Subjects

Jeffrey Masten, Queer Philologies

‘TWELFTH NIGHT’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 13

Maya lights a cigarette.

̶ Viola. Twelfth Night. That’s my favourite role. The one I learned the most from.

Blurring the green and grey in her eyes, the smoke blurs the bounds of her sexuality. She gives me a cocky look, as if she’s Viola again. The blouse that drapes her bustier, however, is no disguise for her curves. Look! Her cigarette crackles and glows as she takes a drag: Now she is eminently the actress, in the masquerade.

̶ It’s a very liberating role. And a lot of fun!

What’s with Raphaël, head down, making a grid of his carrot matchsticks?

̶ A woman disguised as a man—it frees you to act out all you are.

With a stylish tap she flicks her ash into the ashtray.

̶ Androgyny’s a state of mind. It goes beyond sexual orientation.

Her smoke’s getting in my eyes: Why does feminine masquerade move me so?

̶ Gender can be a prison. Take Olivia and Orsino. She with her foolish mourning, dropping out of sexual circulation. He with his silly conception of how a man should love a woman. It’s Viola, the androgyne, who liberates them.

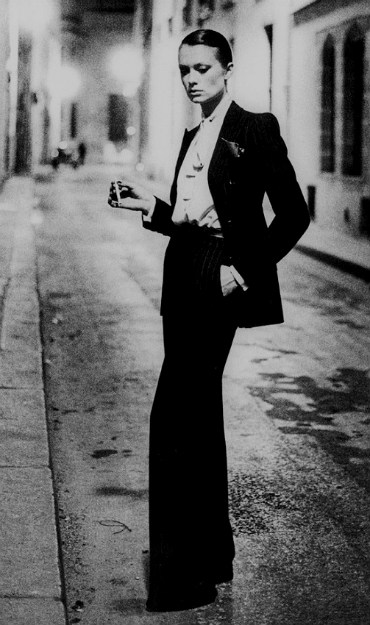

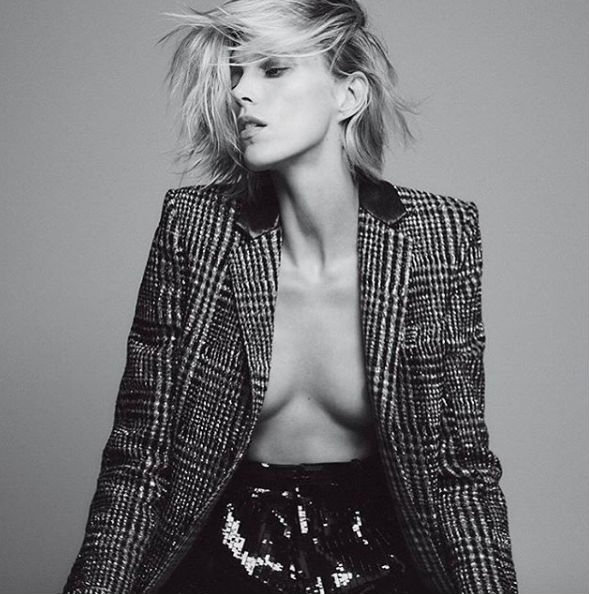

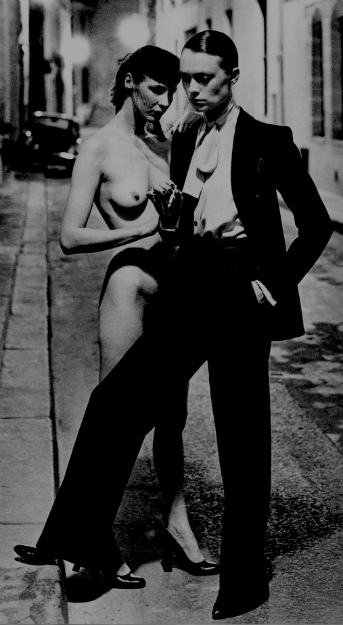

YSL’s Smoking | Photo: Helmut Newton

Designer & photographer: Hedi Slimane

Her hand as graceful as the glass, Maya sips her drink. Resting the glass on the table, with subtle daring she strokes it.

̶ Ever since I played Viola, I’m more able to play with these things.

Indeed. Raphaël, having eaten all his carrot matchsticks, is now unwrapping his prosciutto-bundled green beans and arranging them in a lattice on his plate.

̶ What things? he asks.

̶ Gender. Sex roles. Sex.

̶ And what’s the point?

̶ Fun!

She flicks back her hair: The way it falls into place fills me with a sudden tenderness.

̶ But isn’t androgyny just a fancy word for unisex?

̶ No, Raphaël. It’s the opposite. Androgyny—how shall I put? Androgyny embraces difference. Unisex refuses it.

̶ I don’t get it.

Twirling a ring of orange rind around her index finger, Maya looks at me knowingly and says:

̶ Can you explain, Sprague?

̶ I’ll try.

A little slow to disenthral myself from her cunning fingers (now subtly sliding the orange rind along her distal phalanx), I finally say:

̶ Androgyny’s the bent teaspoon, half in air, half in water. It’s unstable and dynamic, there’s tension. It’s an invitation to play.

Now it’s along the proximal phalanx that she’s fingering the orange peel.

̶ Unisex is the straight teaspoon in an empty glass, static and stable. No tension, no play.

̶ I’m not convinced. Refraction doesn’t explain why unisex and androgyny should be opposite.

Training her ambiguous eyes upon you, Maya asks:

̶ Marietta, can you explain?

̶ I’ll try.

Anja Rubik in YSL, Anthony Vaccarello | Photo: Chris Colls

You sip your Martini, then address yourself to Raphaël.

̶ Have you ever lighted a fashion show?

̶ I have. Yves Saint-Laurent.

̶ Perfect. Now would you agree that the masculinization of women’s clothes, like in Yves Saint-Laurent, intensifies a woman’s femininity?

̶ Intensifies her femininity? Yes. Makes her more sexy—but that’s a paradox!

̶ Exactly. That’s androgyny. It’s paradoxical.

̶ Okay.

̶ Now a man dressed in feminized clothes—is he more masculine?

̶ No. Definitely not.

̶ There you have it. The feminization of men’s clothes does not intensify a man’s masculinity. On the contrary, it diminishes it. There’s no paradox. That’s unisex.

̶ So androgyny is paradoxical and unisex is not?

̶ You’ve got it!

He finishes his drink.

̶ Very clever, your demonstration!

Maya, beaming, blows a series of smoke rings. You pick up the strip of orange rind she’s let fall from her finger and give it to me. Turning to Maya, you say:

̶̶ Now tell me, Maya, did you ever guess, before you played Viola, that disguise could be so fruitful?

̶ I had an idea it would.

She takes a drag on her cigarette.

̶̶ But it went beyond my wildest dreams!

Milky cloud, swirling; evanescent smoke, curling: Who am I?

̶̶ Your dreams weren’t very wild then, were they?

I toss the orange peel back to her.

̶̶ No, I guess they weren’t.

As one, the three of us finish our drinks.

YSL’s Smoking | Photo: Helmut Newton