Don’t Come Knocking

Wim Wenders, 2005

See also TAXI TO PORTUGAL (FAMILY MATTERS)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 10: Bettina

Filigreed silhouettes stir against the calm of the grey-blue sea; wisps of pink float in the transparent sky, a wash of orange and yellow marks the horizon: Dawn over St Brelade’s Bay. Breathing softly in her sleep, Bettina lies sprawled on the bed. Parisian, she’s at Ulm, preparing the agrégation in English literature. Seeking a change of scene, she’d come to Jersey on a whim. I met her in a cinema in St Helier; Don’t Come Knocking, we discovered, had struck a chord in both of us.

Gabriel Mann as Earl

Sarah Polly as Sky

In the hubbub of a pub we created a bubble of privacy, an intimacy made intense by the timbre of her French. Wenders’ tale of Earl and his angel sister, siblings ignorant of each other brought together by the return of a lost father, had us discussing filiation and belonging, home and identity. When the bar closed we didn’t want to part. Outside, under a streetlight, we broke into laughter and embraced: Turned out we were staying at the same hotel.

NEIL CAMPBELL ON ‘DON’T COME KNOCKING’

Neil Campbell is professor of American studies and senior research fellow at the University of Derby, England. The following text consists in condensed extracts from his book, Post-Westerns: Cinema, Region, West (University of Nebraska Press, 2013).

Don’t Come Knocking revolves around Howard Spence’s ‘homecoming,’ or his attempts to reach some resolution in his life through a process of returning. On the one hand, Wenders presents us with the classical Hollywood structure of resolution through the hero’s personal journey tied to the continuity of the film’s action, but then he deliberately reflects upon the inability and problems in achieving the expected ‘happy end, without there being materialized in these images either happiness or the end’ (Jacques Rancière, Film Fables). Thus, the arc of Wenders’s plot in Don’t Come Knocking suggests a transformative epic Western moving its broken hero to some kind of redemption, and yet at every turn he offers up images and scenes in which this is undercut and interfered with, denying the audience any comforting Hollywood final scene. As so often in Wenders’s work, the aesthetic beauty of the film, with its rich colors, expansive landscapes, and intertextual references to art and film, are used as unsettling devices through which we witness the tawdry, broken, and duplicitous world of Howard Spence. Wenders has written that in the West, ‘people here have become the people they’re pretending to be,’ and this is the precise starting point for Howard’s flight (Wim Wenders, On Film).

Sam Shepherd, Don’t Come Knocking, Wim Wenders

Sam Shepherd, Don’t Come Knocking, Wim Wenders

Howard, it transpires, is like an incongruous ghost (a ‘phantom of the West’) haunting the western landscape of Nevada and Montana in search of the various absences of his life (mother, lovers, children). He is the archetypal masculine figure of so many Westerns who abandons the settled and the rooted in favor of the routed, wandering life until, in Howard’s case, his desire is to find a home, a reconstituted family romance. Of course, the mythic tradition of the free-spirited westerner often masks the irresponsibility of abandonment and familial neglect. The ghostly Howard has to be ‘exorcised’ in the course of the film as scene by scene his journey circles back to confront aspects of his shallow life and he must face up to the consequences of his actions. Thus the ‘action hero’ returns to the consequences of his actions in a way unprecedented in Westerns. As one watches, though, it is as if Wenders is also enacting a ritualistic unburdening of his own attachment to the genre itself, both trying to understand its enormity and to find ways to re-evaluate its importance for a new generation.

Paris, Texas begins in Devil’s Graveyard, Texas, a ‘fissured, empty, almost lunar’ desert landscape, out of which wanders a derelict, ghostly, and broken figure named Travis (Harry Dean Stanton). Just as Howard Spence enters the film like ‘the phantom of the West’ and commences a haphazard quest for family and history, Travis’s journey follows a similar course, reconstructing his past from this mythic opening, evocative of a John Ford film, contrasting the heroic tradition of action cinema with the more disjointed, haunted figure of Travis (traversing the mythic), a dislocated man and lost father, without a voice, uprooted, directionless, and outside time. Almost the first words uttered about Travis in the film are ‘Back in the land of the living,’ as if to underscore his ghostliness. In the conventions of Western films, such a landscape of rugged terrain, eagles, and endless vistas would be the site of masculine, decisive action linked inextricably to the hero, but for Wenders, it announces a space where such assumptions are questioned in the complex modern West of family division, suburban sprawl, and corporate global networks. So Howard Spence, our would-be cowboy hero, is not romantically running from the outlaws or the local sheriff, but ironically, given the post-Western nature of the movie, running from Sutter (Tim Roth), a ‘completion bond detective’ hired by the film company to return their investment to the set.

Sam Shepherd, Don’t Come Knocking, Wim Wenders

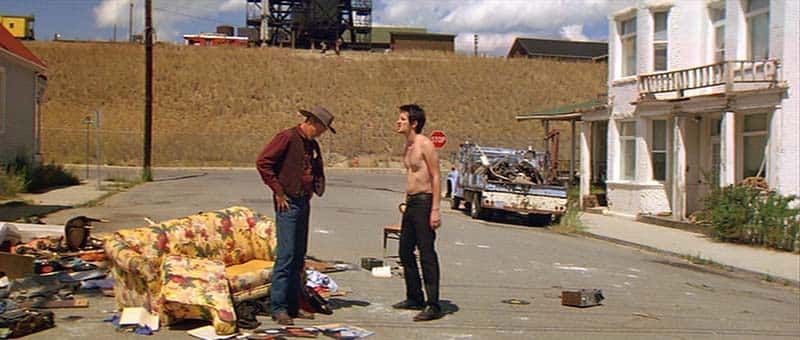

Sam Shepherd and Gabriel Mann, Don’t Come Knocking, Wim Wenders

Similarly Travis’s brother, Walt, works in the advertising industry, building huge billboards that cover over the urban landscape, obscuring its sky. He is an image-maker in a film about images and how they are degraded or exploited as part of an ever-expanding simulacrum. Paris, Texas announces Wenders’s desire to invoke the Western differently. On the one hand, the film recalls the ‘horizon’ and the once mythic themes of settlement, community, family, and heroic individualism he admired in Mann and Ford and which gave him a national story absent in Germany in 1945; on the other hand, it recognizes a postmodern world of fragmentation and loss, family dysfunction, disconnection, and cultural anomie. In these interstices Wenders maps the deterritorialized landscape of the post-Western.

Howard’s memories and fragments return in the course of the film to provoke a reassessment of his life and values. ‘For me,’ Wenders wrote, ‘the American West is the place where things fall apart,’ where one confronts the ‘once mythic,’ the place ‘where the future was supposed to be pioneer country’. In the modern West, Wenders claims, all that pioneer hope and expectation has been reduced, until ‘it’s become a wasteland, where the American dream of the West is expressed in a few forgotten words’ found on the ruined signage of ghost towns or lost highways (Wim Wenders, Written in the West). In Don’t Come Knocking this wasteland is apparent in the casinos of Elko, a ‘hellish world,’ where Howard is drawn into its gaudy, neon-lit promise only to find himself further fragmented and lost. Wenders shoots him at oblique angles and reflected in mirrors and glass to underpin his sense of dislocation and alienation. Becoming increasingly desperate in these scenes, he says, ‘I don’t know what to do with myself anymore.’ He vents his aggression on a boxing machine, which is shot so that he looks as if he is fighting himself, which of course, in one sense, he is. The sequence ends with his being arrested and, like a scolded schoolboy, returned to his mother’s house.

Sam Shepherd, Don’t Come Knocking, Wim Wenders

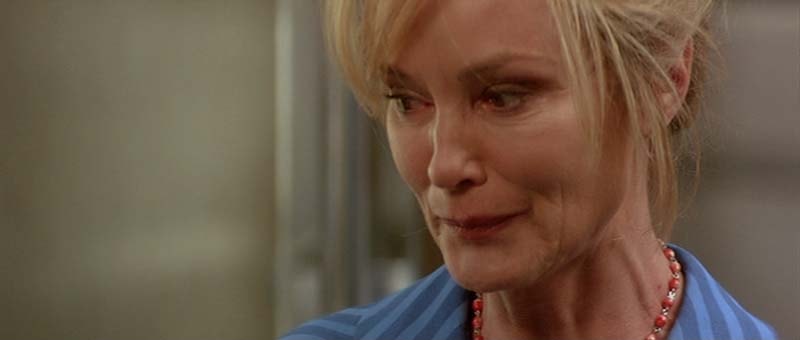

Jessica Lange, Don’t Come Knocking, Wim Wenders

Unsurprisingly, in the two modern Westerns Wenders has made, Paris, Texas and Don’t Come Knocking, there is a definite sense of ruin and loss, of the future interrupted because of a past that hinders and restricts it, of people haunted by the mythic ‘supposed to be’ West and by the consequences of that upon their lives. Thus Travis has been violent and controlling, abandoning and dividing his family, and Howard, as Doreen (Jessica Lange), his ex-lover, points out, is a ‘coward,’ a serial philanderer hanging on to some dream of youth and masculinity who has, as a result, no sense of family loyalty, responsibility, or care. According to Wenders, Howard is ‘the masculine figure par excellence,’ whose assumed status is broken up and interrogated by the presence of determined women. ‘So,’ Wenders says, ‘this is a men’s film carried on women’s shoulders’ (Jason Wood & Ian Haydn Smith, eds., Wim Wenders).

Travis and Howard exist on the ‘brittle surface’ of Wenders’s films, unraveling an exploration of memory, loss, and belonging. Indeed Sam Shepard, who wrote the script for both films, says that Don’t Come Knocking is ‘about estrangement more than anything. It’s about this strange, American sadness that I find, the aloneness they feel. We don’t know each other in America, we don’t even know who we are, we just don’t. I’m haunted by that American character, and that strange, strange lack of identity’ (James Calemine, ‘The Electric Cowboy Stars in Wim Wenders’ Latest Film,’ Swampland.com). Naturally, Shepard endorses the haunting and ghostly quality of Wenders’s vision, that sense of a ‘contagious residue’ from the Western past. How often in Don’t Come Knocking, for example, do we see Howard reflected in windows or mirrors, often doubled or distorted or wandering alone in the spectral streets of Butte like another ghost of cowboys past?

Sam Shepherd and Sarah Polly, Don’t Come Knocking, Wim Wenders

Sarah Polly and Gabriel Mann, Don’t Come Knocking, Wim Wenders

The great beauty of the film, with the fading grandeur of Butte caught in the intense light of morning against an azure blue sky, serves only to heighten the viewer’s disappointment with Howard Spence’s carelessness and irresponsibility. His sense of wasted possibility mirrors the world in which he performs and derives his identity: the American West itself, with its dreams of endless expansion and unhindered progress. Throughout the scene in the street, a low camera angle shoots upward to an American flag flying on an abandoned mining derrick, as if to remind the audience that this is a film about the United States, about its failed vision and the possibility of recovery.