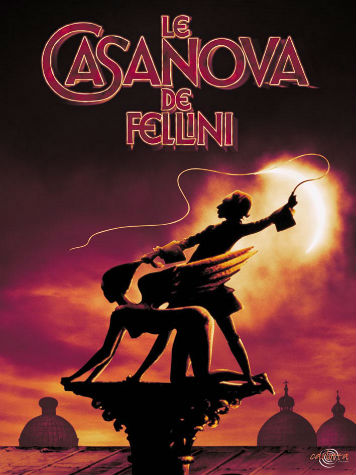

Fellini’s Casanova

Federico Fellini, 1976

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Seven Chapter 4

Fellini’s Casanova: The 205 purrs as we discuss the film you’d seen in the Palazzo dello Strazzino with Matteo and Mara.

The idiot boy

In a witch’s box

On the island of Murano;

Speaking to no-one,

Never spoken to,

Blood from the nose pouring:

Casanova

Donald Sutherland as Casanova

Margareth Clementi as Sister Maddalena

Withholding nothing,

Hoarding nothing,

Giving without calculation;

The scandal of pleasure,

The impudence of daring,

The refusal of shame and guilt:

Casanova

Stealer of fire,

Protector of darkness,

The generosity of the poor;

Lover of women,

Abhorrer of suffering,

The honesty of the outlaw:

Casanova

You laugh when I tell you that between the two of us, it is you who are more fully the Venetian.

We both know that having a roof

Is no assurance of shelter;

We’re both convinced the biggest fool

Is the one who believes he can’t be foolish.

Not for us the familiar mirror,

But the uncanny looking glass;

Not for us the fixity of closure,

But the flux of openness.

Too demanding not to desire the truth,

Too modest to reduce the world to it:

We both know that humility—

Not intelligence—

Is the opposite of stupidity.

So why do I say you are more fully the Venetian? Because the insolence of pleasure becomes you more than it does I.

̶ He’s the brother I never had, Sprague.

̶ He is!

̶ I love his réplique to Voltaire: ‘When you’ve done away with superstition, what will you replace it with?’

̶ Yes, that insight is extraordinary. It’s a shame Fellini failed to understand him.

̶ Nevertheless, the film is still ravishing.

̶ Yes, but if he had understood Casanova, his film would have been—

̶ A different film! You have to accept it for what it is.

̶ Yes, of course. But still. Fellini’s hysterical vengeance against I don’t know what phantasm has nothing to do with the real Casanova.

̶ I agree. But don’t forget that Fellini began as a cartoonist. He’s drawn to caricature.

̶ Right.

̶ And think of the music! Without that clown triste dimension, that ridiculousness, you’d never have that ravishing score.

̶ True. And what a loss that would be!

Listen, my love, to marilenghe, listen to the words in the Friulian tongue:

Pin penin, valentin, pan e vin;

Pin penin, valentin, fureghin.

Le xe le voje i caprissi de chéa,

Che jeri la jera, la jera putéa;

Le xe le voje i caprissi de chéa,

Che jeri la jera, la jera putéa.

Now listen to the music: Wistful, ethereal, otherworldly, through a filigree of plucked guitar the glass harmonica bears the plaintive melody. Punctuated by electric bass, the sonorities are nocturnal. And now the glockenspiel comes to articulate the second motif—’These are the wishes, the whims of the girl, who yesterday was a child, a child at play’—before the acoustic guitar, against a wash of strings, plays the first motif again. How can a nursery song be so heart-wrenching? Is it because, in its very essence, it is an evocation of transience? Listen! In bewitching permutations, in ingenious alternations, the instruments transpose the figure and ground of Casanova as grown-up and child. Marietta, did you ever imagine, as you stared into the aqueous blue of Casanova’s eyes—that pallor abrim with moonlight and spermatozoa—that loving you would turn my green eyes blue and bestow upon my tongue, too, the syntax that turns memory into music?

̶ Miss Charpillon est plus putain que sa mère! Miss Charpillon est plus putain que sa mère! Miss Charpillon est plus putain que sa mère!

Conjuring Casanova’s parrot of revenge, you mockingly convey the spurned lover’s venom. Retrieving your voice, you cut off my laughter.

̶ A brilliant gesture, but much too light to balance the humiliation.

̶ Yes.

̶ Especially when you think he was minutes away from killing himself.

And thus we recalled the facts of the saddest episode in Casanova’s career, when a sweet-faced slut dared him to resist her: She would make him fall in love, she would reduce him to a dog at her feet. She did. Stripped of his dignity, his pockets filled with stones, he crossed Westminster Bridge to drown himself in the Thames.

̶ Could you ever do that to a man, Marietta?

̶ I’ve known men who’ve wanted nothing more than to be a dog at my feet. I’ve never been interested.

̶ Why not?

̶ I don’t like power.

̶ Don’t tell me you’ve never been tempted! Power demands you test it, see how far you can go.

̶ True. But once you’ve made a man cry just because you can, you move on.

Crystalline, the snow glistens.

These are the wishes

The whims of a girl

Who yesterday was a child

A child at play

Unbroken, the plain unfolds its flatness to infinity: The enigma of femininity feeds the vertigo of desire, infinitely.

SEXUALITY AND THE IMAGE OF WOMEN: PETER BONDANELLA ON ‘FELLINI’S CASANOVA’

From Peter Bondanella, The Cinema of Federico Fellini (Princeton University Press, 1992; pp. 307-318)

Fellini’s Casanova, Donald Sutherland

With Casanova, Fellini presents a highly personal interpretation of Italy’s archetypal Latin lover. The contrast between the optimistic and open-ended conclusion reflecting Giulietta’s victory over the malevolent spirits within her (Juliet of the Spirits, 1965), on the one hand, and the far darker, pessimistic, and even morbid analysis of male sexuality in the person of Giacomo Girolamo Casanova (1725-1798), on the other, could not be drawn more sharply. Fellini’s initial attitude toward his protagonist was completely negative. He described Casanova (Donald Sutherland) as a man who has traveled throughout the entire world, ‘but it is as if he never got out of bed. He is really an Italian, the Italian: the indefiniteness, the indifference, the commonplaces, the conventional ways, the facade, the attitude. And, therefore, it is clear why he has become a myth, because he is really nothingness, universality without meaning, a complete lack of individuality, the indeterminate. The film is aimed at being precisely this kind of portrait of nothingness’.

Fellini’s Casanova, Margareth Clementi and Donald Sutherland

Fellini further declared that his total lack of sympathy for the literary persona of the celebrated Venetian adventurer also suggested the ‘only possible point of view’ for his film: ‘A film on nothingness, a mortuary-like film, rendered without emotion. Non-life with its empty forms which are composed and decomposed, the charm of an aquarium, an absent-mindedness of sea-like profundity, where everything is completely hidden and unknown because there is no human penetration or intimacy’.

Yet Fellini’s repeatedly expressed antipathy for the historical figure of Casanova, an extraordinary attitude for an artist engaged in spending millions of hard-to-raise dollars on a film dedicated to that figure, must surely constitute a textbook case of psychological resistance. Whenever Fellini has created extraordinary but despicable male protagonists in his works, such as Zampanó in La strada, his initial aversion to such characters seems to arise from the fact that the director reveals so much of himself in their negative qualities.

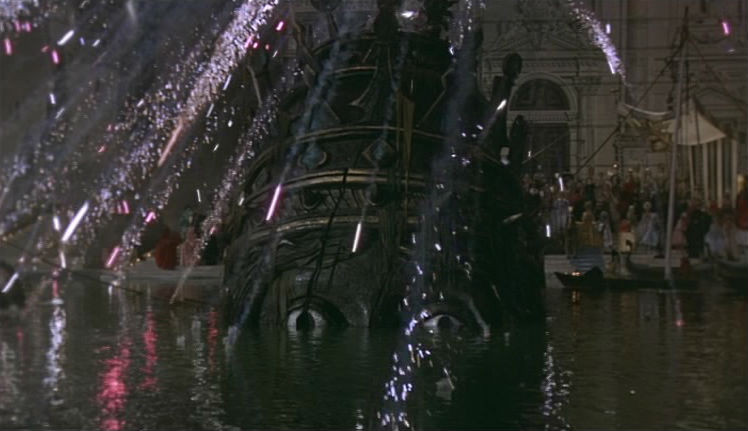

Fellini’s Casanova, Grand Canal, Venice, 1

Casanova must be interpreted from the perspective of the opening sequence, a fanciful creation of a Venetian carnival scene on the lot of Cinecittà. Fellini’s set designer, Danilo Donati, created a Venice of the imagination in which the Rialto Bridge stands near the bell tower on Saint Mark’s Square, an obvious falsification of the actual geography of the city on the sea. On this fanciful city square surrounded by what will soon be revealed to be an equally artificial plastic body of water, Fellini creates a civic ritual celebrated by the Venetians accompanied by original poetry written by his friend Andrea Zanzotto, Italy’s most important living poet. When Fellini asked Zanzotto to supply the lyrics chanted during this opening sequence, he explained the scene in this fashion: ‘It is a ritual that unfolds at night on the Grand Canal, from whose depths must arise a gigantic black head of a woman. A kind of deity of the lagoon, the great Mediterranean mother, the mysterious female who lives in each of us, and I could continue on for a bit, adding with incautious nonchalance other suggestive psychoanalytical images. The ceremony is, in a sense, the ideological metaphor of the entire film; in fact, at a certain point this obscure and grandiose fetish object, not yet completely out of the water, returns to the water’s depths because its pulleys snap and its ropes break; in short, the large head must submerge again, sinking deeply into the waters of the canal and remaining down there forever, unknown and unreachable.

Fellini’s Casanova, Grand Canal, Venice, 2

As the crowd, dressed in traditional Venetian carnival costumes, looks on, their doge, the titular ruler of the republic, grasps a scimitar and cuts a long ribbon, declaring that he is cutting the placenta in order that the figure represented by the large head may be reborn. His action releases a figure dressed as an angel and holding a sword, who descends on a cable from the top of the nearby bell tower toward the water, splashing into the lagoon. As the workmen pull on their ropes, the head that Fellini describes in the letter above slowly emerges from the murky waters. Its sexual connotations are underlined by the crowd as they chant in dialect a refrain: ‘Aàh Venessia aàh Venissa aàh Venùsia.’ This refrain establishes the link in Fellini’s film between Casanova’s birthplace (Venice) and the ancient goddess of love (Venus). But the chant then becomes a bawdy hymn in praise of the submerged sexual powers of what Fellini calls the ‘Mediterranean mother,’ the alluring yet terrifying potential for procreation all women possess that at the same time both attracts men to women and makes them insecure in their presence, since the female reveals to man his own incapacity to give birth to new life: ‘Fornicating cunt, defecating ass, subterranean old hag, stinking old woman, o great cunt, powerful cunt, coquette and embroiler who is given to us by lot as bride and mother, mother-in-law and step-mother, sister and grandmother, daughter and Madonna, we order you with sweat and with work to flourish for him who knows how to seize you.’

Fellini’s Casanova, Grand Canal, Venice, 3

The doge’s reference to the cords of the placenta, and the angel’s sudden immersion into a body of water, make it clear that Fellini’s opening ritual celebrates a birth, Casanova’s, just as the conclusion of the film completes a life cycle and anticipates Casanova’s death. The image representing feminine procreative powers—the head of Venice/Venus—appears but quickly returns to the depths of the murky lagoon, a location suggesting the boundless possibilities of sexual creation, just as the mysterious labyrinth in Fellini Satyricon had symbolized the myriad paths of the psyche. The angel whose immersion into the lagoon’s dark waters triggered the momentary appearance of the great Mediterranean mother Venice/Venus wears a strange corset or waistcoat, similar to the unusual undergarment Casanova wears in every one of his erotic encounters and never takes off even during his most intimate moments. Every viewer of the film has been puzzled by this bizarre costume. One plausible explanation for the garment is that it symbolizes his fear of castration. Such a psychoanalytical explanation would also help to explain Casanova’s sexual athleticism. Born in the shadow of Venice/Venus, and, like every other man, incapable of understanding or performing the ultimate mystery of procreation himself, Casanova can only combat his inadequacy with a frantic and ultimately insatiable compulsion to perform the sexual act over and over again.

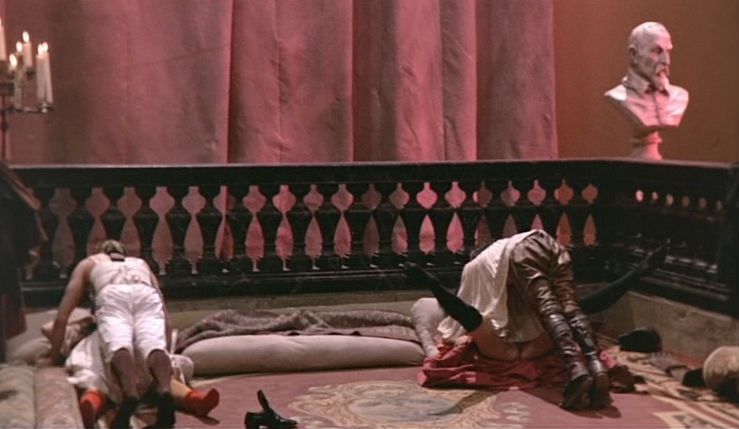

Fellini’s Casanova, the mechanical bird

The compulsive and mechanical nature of Casanova’s lovemaking finds perfect expression in the strange, phallic-shaped bird that he carries everywhere with him, even into prison. The frenetic pumping motion of this mechanical toy, and the strange music that accompanies it on the sound track, suggest mechanical entertainments, such as merry-go-rounds. Moreover, in every instance that Casanova is framed by the camera as he is making love, he repeats the mechanical bobbing up and down of the bird, a movement closer to a gymnastic routine or even a stylized modern dance number than true passion or sexual arousal. Casanova’s amorous liaisons are spectacles or performances, not physical expressions of true emotion. When Casanova makes love with Maddalena (Margareth Clementi), the mistress of the French ambassador, just after the Venetian carnival scene opening the film, her lover observes the spectacle and comments on its fine points afterward. When Casanova makes love with the Marquise d’Urfé (Cicely Browne), as she believes she will be transformed into a man by Casanova’s ‘great work’ in her bed, Casanova is observed by his mistress Marcolina (Clara Algranti), who is forced to uncover her posterior to arouse Casanova’s ardor with the older woman.

Fellini’s Casanova, the sexual contest

Sex is reduced to the level of an athletic event at the home of the English ambassador in Rome, Lord Talou (John Karlsen), who presides over a sexual contest between Casanova and his coachman Righetto (Mario Gagliardo) that is called a struggle between intelligence and brute force, the test of whether the ‘noble savage’ exalted by ‘that great bore Rousseau’ can match a ‘gentleman with style and culture.’ At the Albergo dei Mori in Dresden, Casanova encounters a troupe of Italian opera singers and a former mistress named Astrodi (Marika Rivera), who introduces Casanova to a hunchbacked actress with an enormous red tongue (Angelica Hansen). The encounter ends in an orgy in which Casanova copulates with a good part of the troupe while onlookers on the balcony masturbate, combining the notion of theatrical spectacle with that of mechanical sex. The usual mechanical music accompanying Casanova’s bird speeds up and slows down exactly like that of a music box needing rewinding. This sense of lost energy is appropriate at that point in the film, since Casanova is rapidly approaching old age and death.

Fellini’s Casanova, Donald Sutherland

When Casanova finally reaches the end of his life in Bohemia, where he serves as the librarian to the castle of Dux, he has a dream of his native Venice which Fellini re-creates on the set where the head of Venus/Venice had sunk into the lagoon during the opening carnival sequence. Now we see the lagoon at night during the winter: the air is filled with fog and the water is frozen over, but underneath the ice Casanova can still discern the eerie eyes of the head gazing toward him and us. A number of the women in his life appear (including his mother), but they all run away and vanish on the ice. The pope, in a golden carriage, smiles at Casanova in a paternal way and motions to a figure nearby. It is Rosalba (Adele Angela Lojodice), a beautiful mechanical doll with whom Casanova had years earlier danced at the court of Wurttemberg and with whom he had made love in one of the few instances during his life when his passion was not accompanied by his mechanical bird. Casanova goes to Rosalba on the frozen lagoon, and after an extreme close-up of Casanova’s old, bloodshot eyes, the camera frames the two dancing upon the ice. But now Casanova and the doll make no movements: Casanova’s mechanical life and his frenzied sexual appetites have transformed him, like Rosalba, into a mechanical man who turns around and around with his partner on the frozen lagoon as if he were a cog in a machine.

Fellini’s Casanova, the giantess and a dwarf

Fellini’s Casanova, Donald Sutherland

I have already suggested that Casanova’s sexual athleticism, manifested through the Venetian’s mechanical perspective on sexuality, may well be the product of a sense of inferiority when confronted with the female and her potential for procreation. This idea finds substantial confirmation in one of the most unusual sequences of the film, that set in London. After Casanova is unceremoniously thrown out of a carriage with his mechanical bird by Madame Charpillon and her daughter (both his mistresses), he decides to commit suicide and walks into the Thames with rocks in his pockets, reciting the lyric poetry of Torquato Tasso (another man of letters that the Romantic period saw as destroyed by love). At the last moment, he spots a gigantic woman on the shore and decides to live, following her to a nearby circus. There, although Casanova does not realize that the woman (Sandy Allen) has disappeared into the body of an enormous female whale, Casanova sees a long line of men marching silently into the mouth of the whale, called by a circus barker ‘La grande Mouna.’ But the whale is clearly a euphemistic image for the female womb, a fact underlined by the name given to it by Tonino Guerra’s verse which the barker shouts (‘Mouna’ suggests the Venetian word ‘mona’ or ‘cunt,’ the key word in the chant opening the carnival scene). In addition, at least one of Fellini’s preparatory drawings, published in Zanzotto’s volume of verse written for Casanova, portrays the scene with a huge nude woman, not a whale, through whose outstretched legs the lines of men at the fair march.

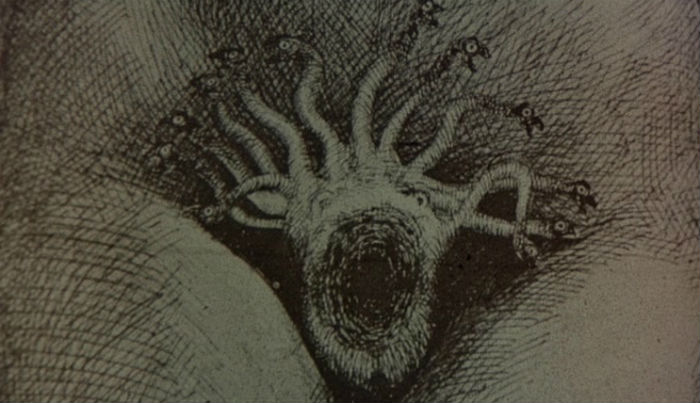

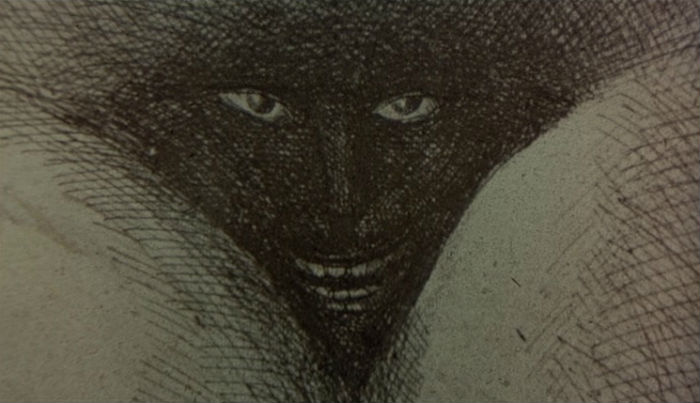

Fellini’s Casanova, drawing by Roland Torpor, 1

Fellini’s Casanova, drawing by Roland Torpor, 2

Fellini’s Casanova, drawing by Roland Torpor, 3

Fellini’s Casanova, drawing by Roland Torpor, 4

Inside the body of the whale/womb, Casanova encounters a magic lantern, the forerunner of the contemporary cinema, projecting frightening drawings by Roland Topor of the vagina dentata: they depict the female sexual member as a vortex into which men are dragged, as a spiderweb, and even in the likeness of the devil. This link of the projection of male sexual fantasies (or fears) to the Enlightenment equivalent of the cinema cannot help but recall Fellini’s views on the feminine qualities of the cinema that were cited earlier in this chapter. In Fellini’s early works, we have already observed how the director will frequently modify early versions of his scripts to tone down the overly obvious thematic ideas, preferring instead to rely on the evocative power of the image rather than the sometimes overly didactic dialogue. Bernardino Zapponi’s prose ‘retelling’ of the film in novel form probably reflects an earlier version of the script later modified during shooting or in editing when he describes Casanova’s entrance into the whale in this fashion: ‘At last Casanova is back in the womb,’ says a voice. Who said that? Casanova wheels. No one is there (The voice was Fellini’s). The spectacle that unfolds in the little whale-theater is amusing, if a bit shocking. A magic lantern projects images of female freaks on a screen. There are toothed vaginas, deformed bodies, and all the other features of a typical eighteenth-century ‘summa monstruorum’. Giacomo looks on, fascinated by these horrendous deformities. Is this not perhaps, deep down, what women are really like? Is this the archetypal female to whom he, the eternal boy, is unconsciously drawn? Or is it a being to flee from—the terrible Vagina Dentata of legend?’.

Fellini’s Casanova, giantess and two dwarfs taking a bath

From Zapponi’s retelling of the film’s narrative, it is obvious that Fellini originally planned personal interventions into the screenplay similar to those we have already discussed in Amarcord. Later, realizing that such obvious emphasis on the film’s narrative themes was unnecessary and relying, as usual, on the expressive powers of the visual image, Fellini suppressed the temptation to interject his personal commentary into this sequence. But Zapponi’s version does reveal the ambivalence toward the female that runs through this sequence. While the images projected by the magic lantern of the vagina dentata haunt the dark recesses of Casanova’s psyche—and that of his creator—the giantess Casanova followed to the whale/womb and whom he meets there inside the animal’s belly continues the theme of ambivalence toward women. She first defeats Casanova and a number of other men in tests of strength, thereby giving substance to male fears of the female’s awesome powers. But later, as she bathes with her two dwarf attendants, she hums a childhood lullaby, ‘Cantilena londinese,’ composed by Zanzotto for the sound track. She thus embodies a maternal aspect mysteriously combined with her awesome powers to overwhelm her male admirers.

Fellini’s Casanova, Casanova and the mechanical doll

Fellini has called Casanova’s Memoirs only an aggravating ‘telephone book of artistically non-existent and sometimes most boring occurrences,’ and its author a proto-Fascist, an anticipation of the personality type depicted in Amarcord characterized by ‘protracted adolescence.’ And yet, as always, Fellini’s negative judgment of his embattled protagonist from the perspective of the prosecution is mitigated by extenuating circumstances brought forward by the major witness for the defense, the director himself. The final image of Casanova as an old man dreaming of his native Venice and dancing a last waltz upon the frozen lagoon with a mechanical doll, the only woman in his entire life he has really understood and whom he emulates in his last moments on the screen by becoming a mechanical creation himself, cannot be judged too harshly. As one critic has accurately described it, this closing vision is a celebration of the imaginative act of the artist, which, like the ice, can freeze an image and hold it before the mind’s eye. It is this implicit parallel between the aging Venetian rake and the no longer youthful director that ultimately moves Fellini to pardon Casanova’s faults and to admit him to the pantheon alongside other flawed male protagonists in his cinema—Zampanó, Marcello, and Guido, to mention only the most important—who were just as incapable of comprehending the ultimate mystery of Woman as Fellini has shown Casanova to have been.

Casanova’s confrontation with the Eternal Feminine constitutes a tragedy, in part precisely because he serves Fellini as an alter ego, representing the figure of the artist confronted with old age and mutability.

Fellini’s Casanova, Donald Sutherland