You can listen to the tracks in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

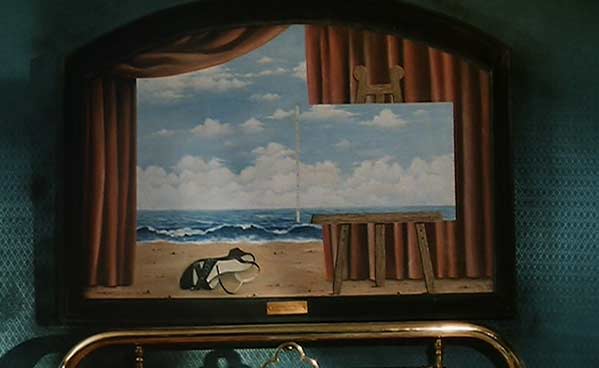

La Belle Captive

Alain Robbe-Grillet, 1983

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 11

̶ I woke up this morning thinking it all a dream.

So I say as, through whimsical splashes of shadow and light, we walk around the Fontaine de Medicis.

̶ That’s funny—I dreamt you were dreaming about it! And when did you realize it wasn’t a dream?

̶ When I was having my coffee. It was only then I remembered we’d seen the film last night.

̶ That’s a tribute to Robbe-Grillet. I’m sure he’d be pleased to hear that.

Gabrielle Lazure as Marie-Ange van de Reeves

Bordering the pond, on pillars that punctuate the balustrade, classical urns of begonia and painted nettle prolong the autumn. I ask you:

̶̶ Do you agree there are at least three levels of reality in the film?

̶ Yes. But that’s the easy part.

And thus we came to discuss La Belle Captive, a cinematic gem by Alain Robbe-Grillet; and thus, in so doing, we came to confront our visions of men and women at play. The ghost of our conversation still haunts the fountain; listen as I conjure it now.

On bright red stems amidst bronze-green leaves, orange flowers cascade from a concrete urn: I pluck one and stick it in your hair. Bending me over the balustrade, you take my head in your hands; soft on my throat your lips glide, hard on my skin your teeth bite.

̶̶ Aïe!

̶ Be careful, Sprague, lest a woman’s enigmatic smile lead you to perdition.

You take my hand and lead me towards an urn of painted nettle.

̶ You’d have been a better Marie-Ange than Gabrielle Lazure!

̶ No, she was perfect. But the vampire dimension could have been done better. It needed a little more horror and fascination, don’t you think?

̶ Yes. The eroticism lacked intensity.

Deep-purple is the heart of the nettle’s brick-red leaves; yellow-bright their border. I continue:

̶̶ It’s a shame, because had the sex been more powerful, Robbe-Grillet’s game between ‘real’ and ‘represented’ would have worked even better.

̶ It’s tricky for him, because he always wants distanciation.

̶ True. But cinema is an art of emotion. With just one close-up of Anna Karina, Godard could redeem his didacticism.

Cyrielle Clair as Sara Zeitgeist

Bending me over the balustrade, you take my head in your hands; soft on my throat your lips glide, hard on my skin your teeth bite.

̶ Aïe!

̶ Beware, Sprague. A woman’s enigmatic smile can lead you to perdition.

̶ Then I’ll go for the sexual power of Sara Zeitgeist! How did you find her?

̶ Hot!

̶ Cyrielle Clair, she was great. The dark angel of death!

̶ Yes, she was radiant, luminous!

Floating leaves part in the pond, revealing our reflections in the water: We couldn’t see ourselves joined in one breath, but we did feel the curtains drawing back.

̶ It’s sex, isn’t it? I ask. All those scenes of going through. The passage through the proscenium, the bite into the blood, the paintings you pass through.

̶ Yes, of course. But it’s also the penetration into other worlds. The world of the dead, for example, coexisting with the world of the living.

̶ As in Walter and Henri de Corinth?

̶ Yes, but above all in Marie-Ange.

̶ What do you make of her, in fact?

̶ Well, she’s Walter’s fantasy, of course, and she’s a vampire. And when it comes to crossing boundaries, you can’t beat the vampire, can you?

̶ No, I suppose not.

̶ She exposes his limits, she reveals his anxieties about sex.

̶ Yes, I noticed how passive he is when Marie-Ange makes love to him. I saw that as an experiment on his part. He deliberately wanted to give up control.

̶ Isn’t sex always an experiment?

̶ Yes, I guess it is.

̶ Marie-Ange confirms Walter’s existence. That’s why she has to be so aestheticized, so objectified.

̶ He both desires her and is afraid of her.

̶ That’s the duality of the cliché: the virgin and the vampire. Every woman knows how it works.

̶ Is a man’s desire really so transparent?

Looking at me askance, you give me your sly smile, then take my hand and lead me to an urn of bonfire begonia.

̶ And what did you think of Robbe-Grillet’s use of Magritte?

You hesitate before replying, as if seeking a way to embody your response. And then you simply say:

̶̶ It’s brilliant! You end up not knowing which world is real, the one behind the curtain, or the one in front. Exactly as in dreams.

̶ Yes. And did you notice how each successive vampire bite makes Walter weaker?

̶ I did. And the weaker he gets, the deeper he penetrates into the world beyond the curtain. But what he doesn’t understand—poor guy—is that it’s his own death they’re staging.

̶ He doesn’t understand, because the moment he comes across Marie-Ange lying bleeding on the road, he’s continually distracted from the mission Sara Zeitgeist gave him. When Marie-Ange disappears, he gets caught up in the investigation—as detective and suspect. He never accomplishes his mission.

Daniel Mesguich as Walter Raim

̶ He doesn’t, and so he doesn’t discover his own story. That, of course, was the point of the mission Sara gave him.

̶ Yes.

̶ And because he doesn’t discover his own story, because he fails to grasp that digressions are the story, she condemns him to death.

̶ It’s the story of Oedipus.

̶ It’s the story of all abandoned sons.

̶ But what if he could have found—

Bending me over the balustrade, you take my head in your hands; soft on my throat your lips glide, hard on my skin your teeth bite.

̶̶ Aïe!

̶ Remember, Sprague, what Sophocles said: He who knows not his origins is damned.

̶ Yes, but—

̶ The child Oedipus, the lost little boy who knows nothing of his filiation, grows up to become an assassin.

Still the bright yellow leaves, edged in green, defy the glory of your eyes: Still your eyes put them in the shade.

̶̶ I do remember, Marietta. Didn’t I write The Dustman’s Daughter?

̶ You did. But you displaced the incest from mother-son to sister-brother.

It hits me, your observation, it hits me with the same impact as before.

̶̶ Yes.

You smile enigmatically, take my hand and lead me to an urn of bonfire begonia.

You relaunch our conversation:

̶ I like the way The Execution of Maximilian prefigures Walter’s execution.

̶ The scene where he’s going back upstairs to the bedroom?

̶ Yes.

̶ That whole sequence where Walter’s finding his way in the flooded villa—the fluttering veils, the water in the passageways, the dark corridors—that’s the sequence I like best in the whole film.

̶ It’s lovely, yes. And it made the whole movie clear to me. The darkness, the water, the mysterious wind—Walter is walking through his own unconscious, pursuing a woman who’s just a projection of his fantasy.

̶ But how else could he discover himself, Marietta?

̶ True. He is a man, after all.

̶ And doesn’t he have to die, doesn’t he have to submit to his own execution, before he can find himself?

̶ Of course. Just as Oedipus had to plunge Jocasta’s pins into his eyes.

̶ Only the blind can see?

̶ Yes. The rest of us, when all is said and done, are just pursuing phantoms, mistaking one another for the one we want them to be.

You take my hand.

̶̶ Let’s go over there, Sprague.