The Development of the Novel

PATRICK WHITE: VOSS – BACKGROUND FOR AN ANALYSIS

David Marr

From David Marr, Patrick White: A Life (London: Vintage, 1992) pp. 300, 311-318

Slightly edited to smooth the elisions required to keep the focus on Voss

and to make explicit (often via interpolations in square brackets) the allusions to previous pages in the biography.

Text in gold type within the body of the post is a citation (from Voss, PW’s letters or interviews, or other sources) and so accounts for my dispensing with quotation marks. (RJ)

Patrick White | Rick Amor, 1990

I. INTRODUCTION

Patrick White had been a long time pregnant with Voss. Conceived in London during the Blitz, the explorer novel grew in his imagination in the Western Desert, found its true character in the Mitchell Library on his reconnaissance in Sydney but was then put aside in bitter apathy after the failure of The Aunt’s Story. Now as White lay in the public wards of Sydney hospitals in the summer of 1954-55, battered by the most violent asthma attacks for nearly twenty years, the novel came back to life. The fevers of Voss and the hallucinations of Laura Trevelyan grew out of his own suffering that summer in the attacks first triggered by the indifference of his agent at Curtis Brown, Juliet O’Hea, to The Tree of Man. All summer these bouts returned as bad news about the book continued to arrive from London. Yet this hostility stimulated him profoundly and The Tree of Man crisis set a pattern for his life. White was driven by the need to show his detractors, to vindicate himself with the next novel. Even in the midst of triumphs, White sought hostility as a spur to his art.

Patrick White, The Tree of Man & The Aunt’s Story

Back at Dogwoods [his farm on the outskirts of Sydney], frail but breathing, White began a course of allergy injections. He fell ill again; blamed the injections; took antidotes; and by the New Year of 1955 was feeling restored. But when the next bout of asthma came in January, it was the worst he had ever suffered. After a fortnight gasping in bed at Dogwoods, he was taken down to Royal North Shore Hospital. In my half-drugged state the figures began moving in the desert landscape. I could hear snatches of conversation, I became in turn Voss and his anima Laura Trevelyan. On a night of crisis, with the asthma turning to pneumonia, I took hold of the hand of a resident doctor standing by my bed. He withdrew as though he had been burnt. The doctors warned Lascaris [White’s life partner] that White could only expect to live five years with his lungs in such a state. As he recovered in the ward, White began working on the skeleton of Voss.

Australian Outback | Photo: Ash Jurberg

II. THE THEME OF SUFFERING

Suffering is a theme that runs through all White’s work, but Voss is, more than any of his other novels, an account of its virtues. Mahatma Gandhi wrote: It is impossible to do away with the law of suffering, which is the one indispensable condition of our being. Progress is to be measured by the amount of suffering undergone. The purer the suffering, the greater the progress. White had used those words as an epigraph for Happy Valley. Twenty years later they could have served as well for Voss.

Mahatma Gandhi, 1940s | Patrick White, Happy Valley

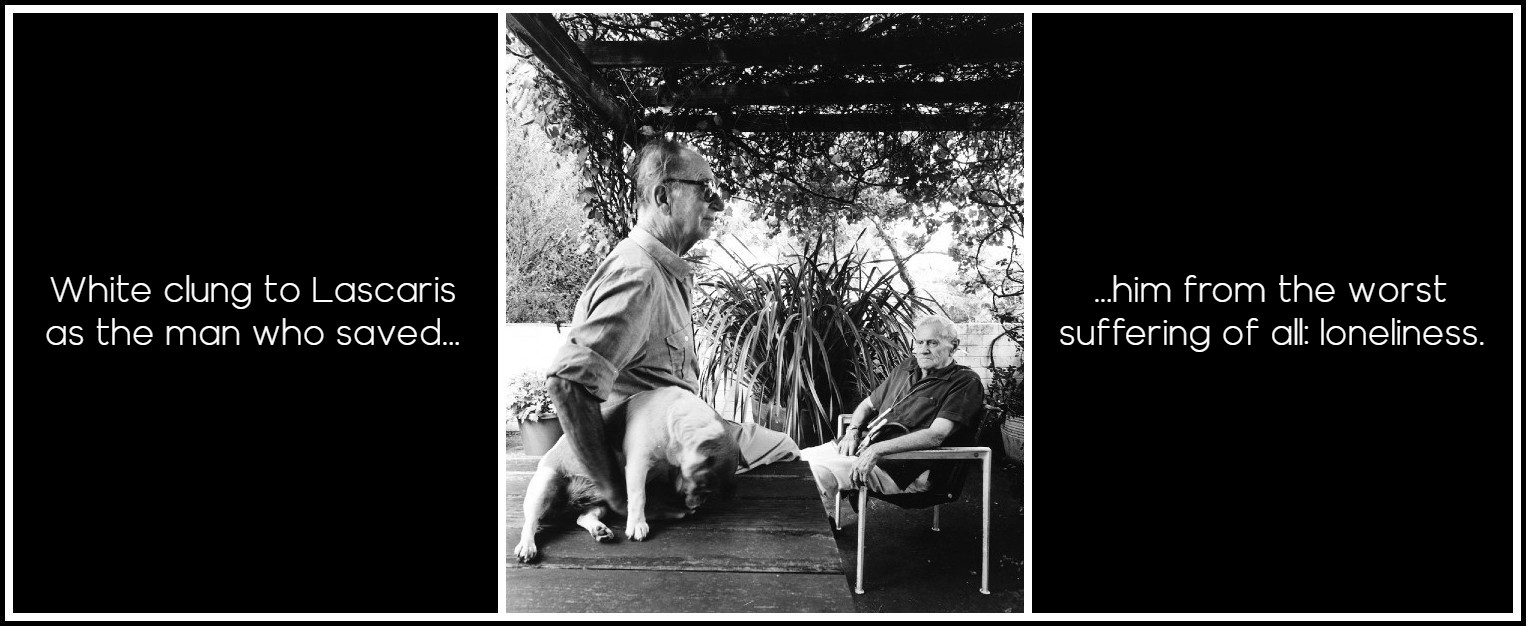

White was aware that his own sense of suffering was, at times, exaggerated; he knew that money had saved him from many of the ordinary miseries experienced by the human race; he clung to Lascaris as the man who saved him from the worst suffering of all, loneliness.

Manoly Lascaris & Patrick White | Photo: Max Dupain, 1987

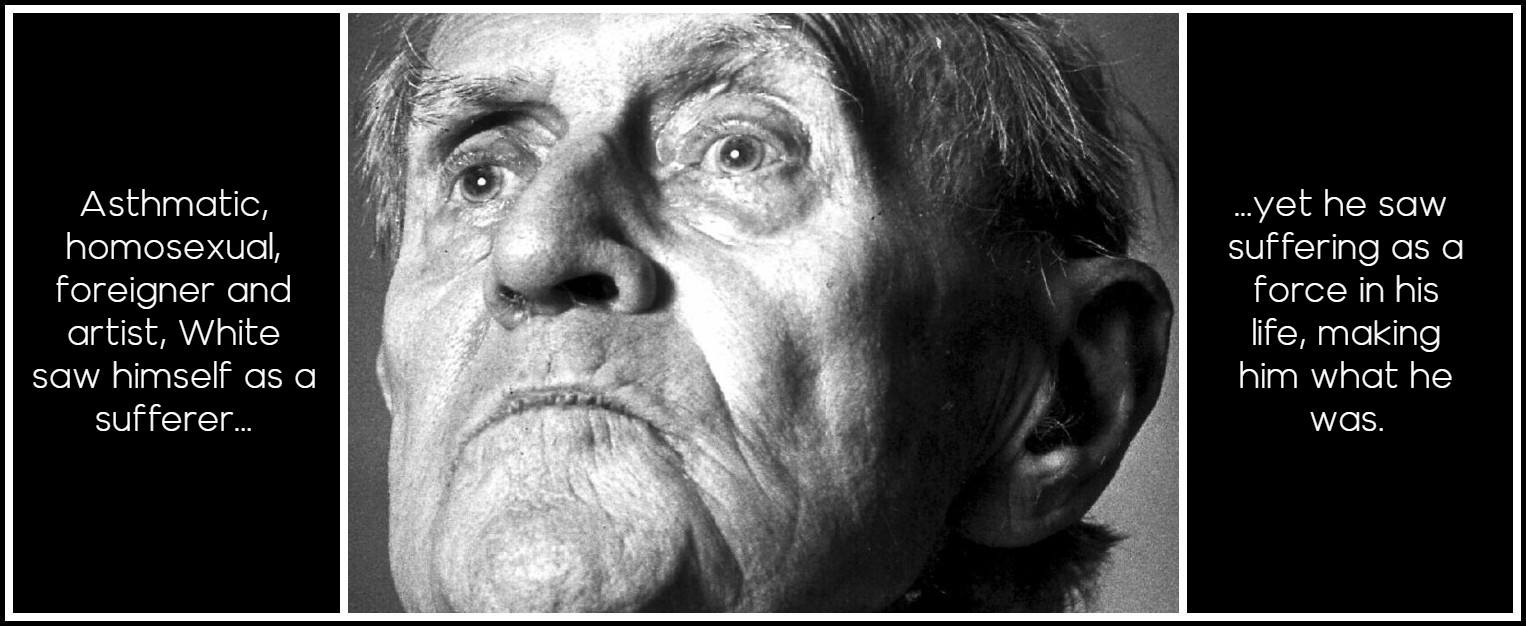

Asthmatic, homosexual, foreigner and artist, White saw himself as a sufferer, yet he saw suffering as a force in his life, making him what he was, making us as we are. For him, pain is a force of history, shaping men and events. I have always found in my own case that something positive, either creative or moral, has come out of anything I have experienced in the way of affliction.

Patrick White | Photo: Max Dupain, 1986

Behind the sufferings of Johann Ulrich Voss in the Australian desert lay the pain White experienced writing The Tree of Man. Both men were explorers: Voss on horseback crossing the continent and White at his desk trying to fill the immense void of Australia. Writing of the two expeditions, White used the same rhetoric of men stripped bare of almost everything they once considered ‘desirable and necessary’ in order to realise their genius. Every man has a genius, pronounced Voss, though it is not always discoverable. Least of all when choked by the trivialities of daily existence. But in this disturbing country, so far as I have become acquainted with it already, it is possible more easily to discard the inessential and to attempt the infinite. You will be burnt up most likely, but you will realise that genius. Voss’s expedition was not a failure, though he found no new pastoral Eden, made no maps, lost all the specimens his party collected, and failed to reach the sea on the far side of the continent. Through his suffering in the desert, Voss conquered his pride.

Australian Outback | Photo: Michael Skopal, Unsplash

III. THE THEME OF PRIDE

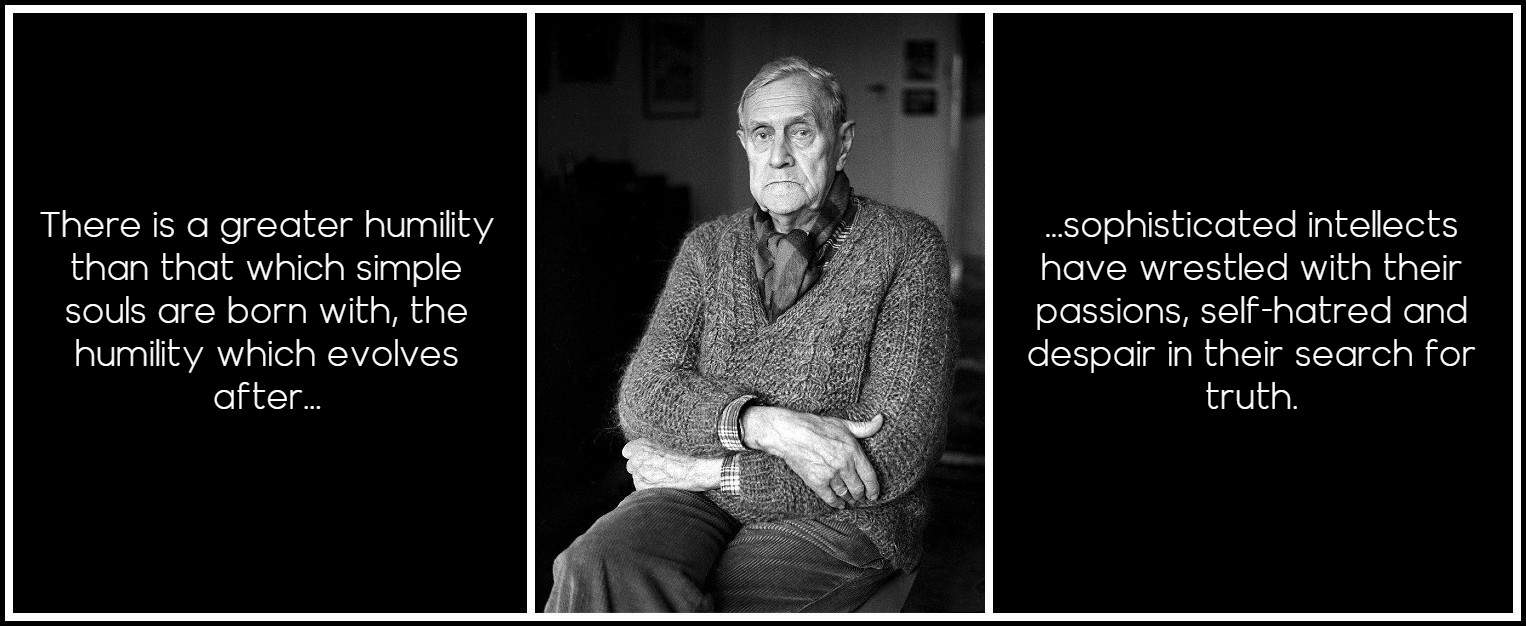

White’s fear of pride appears to have intensified at the time of his religious conversion. Lizzie Clark [his nanny-governess] had issued decent Presbyterian warnings to the boy but, after he fell in the rain and cursed God [whereupon he found faith], White went further than anything she had encouraged. He spoke of searching for humility. Certainly the state of simplicity and humility is the only desirable one for artist or for man. While to reach it may be impossible, to attempt to do so is imperative. The Parkers on their farm at Durilgai1 were lucky, for they possessed all along the humility White was now seeking. It was in their blood. This new imperative was all the more urgent in the face of the success of The Tree of Man, for he had an absolutely sure grasp of the dangers pride presented to an artist. He was proud—Withycombe assurance and White money had seen to that—and now he was afraid of his pride. Of all the failings he saw within himself, this was the one he was most determined to conquer. He never did. From the first it was an unequal struggle, yet he persisted. The struggle took many forms. In the early years of his faith he prayed. Then, and later, he sought to mortify his pride through suffering. There is a greater humility than that which simple souls are born with, the humility which evolves after sophisticated intellects have wrestled with their passions, self-hatred and despair in their search for truth.

1 – The Tree of Man

Patrick White | Photo: William Yang, 1985

White put much the same grim warning in Laura Trevelyan’s mouth after she had attended the unveiling of a statue to the lost explorer Voss. Knowledge, she says, was never a matter of geography. Quite the reverse, it overflows all maps that exist. Perhaps true knowledge only comes of death by torture in the country of the mind.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Christabel, 1867

IV. THE GENESIS OF ‘VOSS’

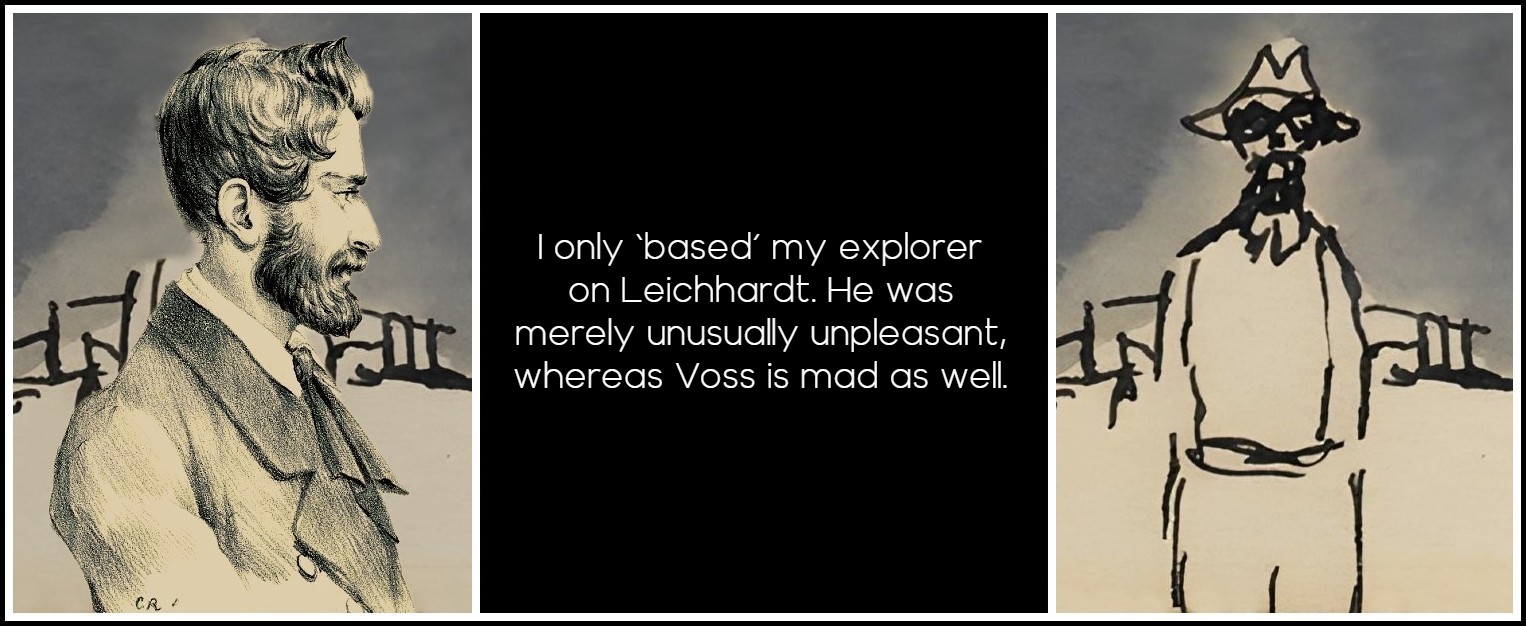

White had been working on Voss for eighteen months through all the dramas attending the publication of The Tree of Man. He was, as usual, very secretive about his writing. The second draft of Voss was finished soon after The Tree of Man appeared in Australia. White then put the manuscript aside for a few weeks and began the final typescript in the spring of 1956. Not until this was well under way did he tell his publishers anything very much about the new novel. He wrote to Ben Huebsch [his publisher-editor at Viking in NYC] in September: Some years ago I got the idea for a book about a megalomaniac explorer. As Australia is the only country I really know in my bones, it had to be set in Australia, and as there is practically nothing left to explore, I had to go back to the middle of the last century. When I returned here after the War and began to look up old records, my idea seemed to fit the character of Leichhardt. But as I did not want to limit myself to a historical reconstruction (too difficult and too boring), I only based my explorer on Leichhardt. The latter was, besides, merely unusually unpleasant, whereas Voss is mad as well.

Ludwig Leichhardt (Artist: Charles Rodius) | Johann Ulrich Voss (Artist: Sydney Nolan)

I also wanted to write the story of a grand passion. So this is at the same time the story of a girl called Laura Trevelyan, the niece of a Sydney merchant, one of the patrons of Voss’s expedition. It is different from other grand passions in that it grows in the minds of the two people concerned more through the stimulus of their surroundings and through almost irrelevant incidents. Voss and Laura only meet three or four times before the expedition sets out. They even find each other partly antipathetic. Yet, Voss writes proposing to the girl on one of the early stages of the journey, partly out of vanity, and partly because he realizes he is already lost. She accepts, partly out of a desire to save him from his delusions of divinity; partly out of a longing for religious faith, to which she feels she can only return to through love. As the two characters are separated by events and distances, their stories have to be developed alternately, but they do also fuse, in dreams, in memories, and in delirium – most closely, for instance, when Voss is lying half-dead of thirst and starvation, and Laura is suffering from delusions as the result of a psychic disturbance diagnosed as the inevitable ‘brain fever’. Voss is finally dragged from his golden throne, humbled in the dust, and accepts the principles Laura would have liked him to accept before he is murdered by the blacks. Laura recovers. She becomes a headmistress, and figure of some respect in the community, if also one that nobody really understands, because of some mysterious past.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Christabel | Douglas Kilburn, Three Aboriginal People

You will see that there is a lot that has to be made convincing. I want to include the crimson plush and organ peals, while making them acceptable to the age of reason by a certain dryness of style. To a certain extent the style is based on that of records of the day, but I have also left some loopholes through which to get my own effects. Two of the practical difficulties have been to try to make an unpleasant, mad, basically unattractive hero sufficiently attractive, and to show how a heroine with a strong strain of priggishness can at the same time appeal. As for the look and the sound of the thing, I have tried to marry Delacroix to Blake, and Liszt to Mahler. Now I really am committed to my own shortcomings! And on reading over what I have written, I see I have failed to convey that there are lots of subsidiary characters, minor alarms and excursions, deaths by thirst, a suicide, an illegitimate child, picnics, balls and weddings.

Patrick White, Voss, Penguin cover (detail) | Julia Margaret Cameron, Christabel

The essence of Voss was White himself: Bits of Leichhardt, bits of John Eyre [an explorer whose journal ‘electrified’ White], and I suppose, some of the others, but there is more of my own character than anybody else’s. He gave Voss the ‘gabled town’ of Hanover as his birthplace, and his first explorations were conducted on the sandy heath that surrounds the city White knew best in Germany.

Patrick White: Penguin cover of Voss (detail) | Drawing by Louis Kahan

V. CHARACTERS: BELLE, LAURA, BONNER, PALFREYMAN

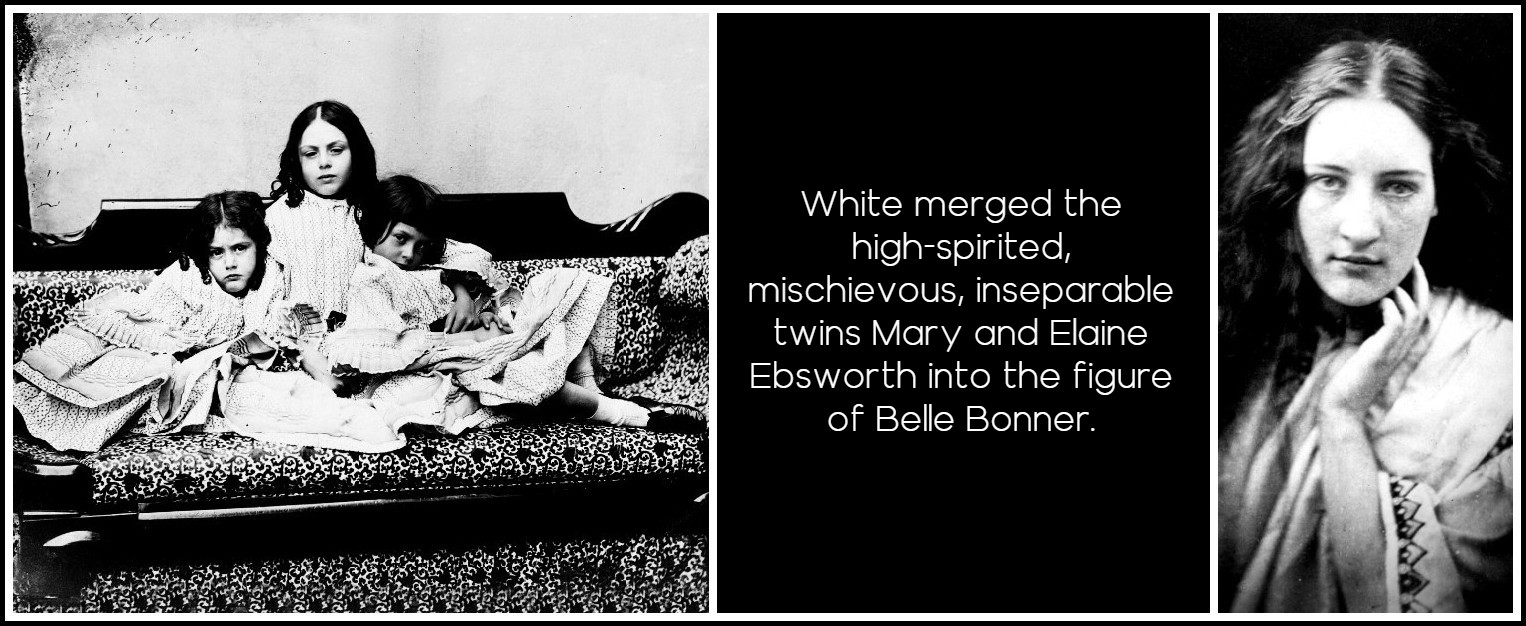

White’s heroine Laura Trevelyan and her cousin Belle Bonner grew from his memories of the Ebsworth children [PW’s cousins]. The Ebsworth family appear in many guises in his writing. Charles Ebsworth, the tall, stuffy solicitor who looked after the affairs of his parents, had already appeared as Dudley Forsdyke in The Tree of Man. He is the lawyer the Parkers’ daughter marries: a dry man, but a true man. The Ebsworths had three daughters. When the high-spirited, mischievous, inseparable twins Mary and Elaine came to Lulworth [PW’s childhood home] they ragged the boy they called ‘poor old Paddy’, for they felt he was a misfit and rather pathetic. These two—always on the run, plaits flying, undisciplined and haughty—he merged into the figure of Belle Bonner.

Lewis Carroll, Edith, Ina & Alice Liddell, 1858 | Julia Margaret Cameron, Hattie Campbell, 1868

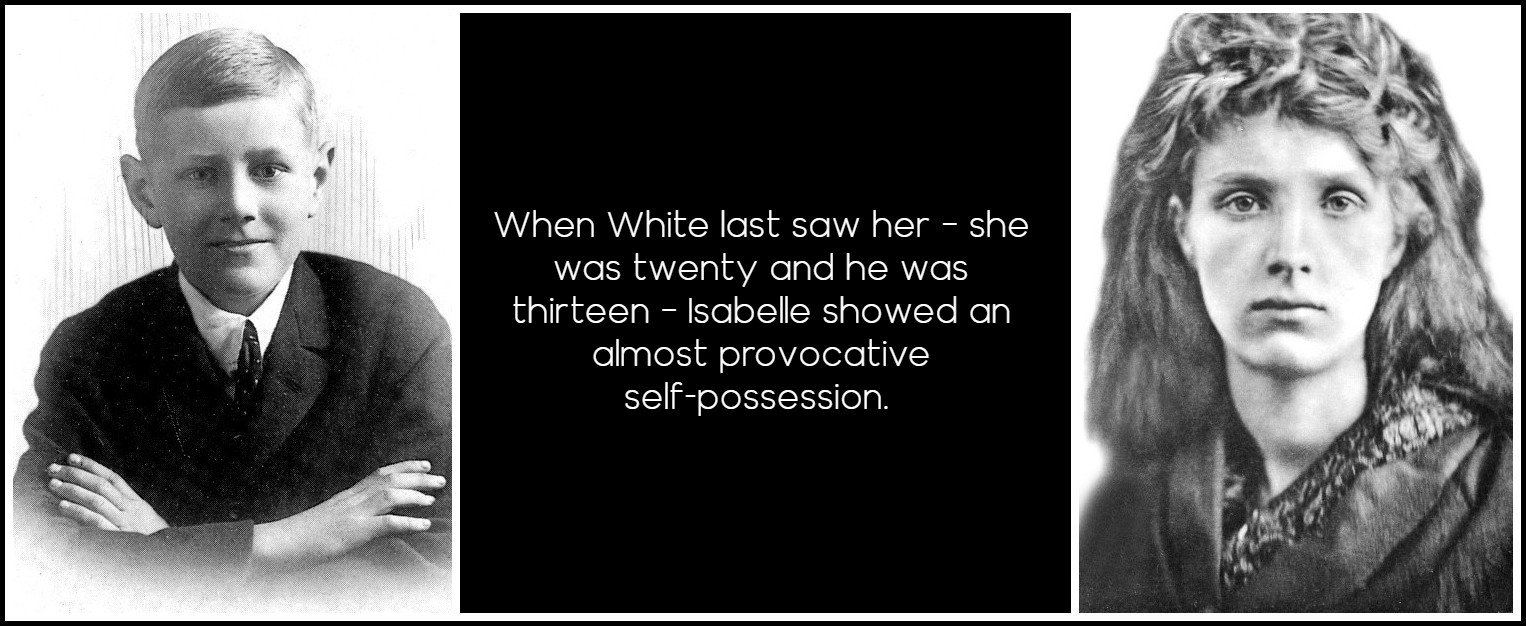

From their older sister Isabelle, the boy sensed a measure of intuitive sympathy. This became the core of Laura Trevelyan’s character. Isabelle Ebsworth was years older than the twins, intense, and with a face of great interest. She had a dramatic jaw and wide green eyes cut at a slant. The Ebsworths held her out to be the brainy one of the family, but she was not at all cold. Even when White last saw her—she was twenty and he, about to leave for school in England, was thirteen—Isabelle showed an almost provocative self-possession. She attracted idealistic suitors. By the time White was working on Voss she had divorced, moved to Scotland and married a Glasgow psychiatrist. Once in later years she and White arranged to meet in Scotland but the plan fell through. They never met again.

Patrick White at age 12, 1924 (Photo: Norman Studios, Sydney) | Julia Margaret Cameron, Sweet Liberty, 1886

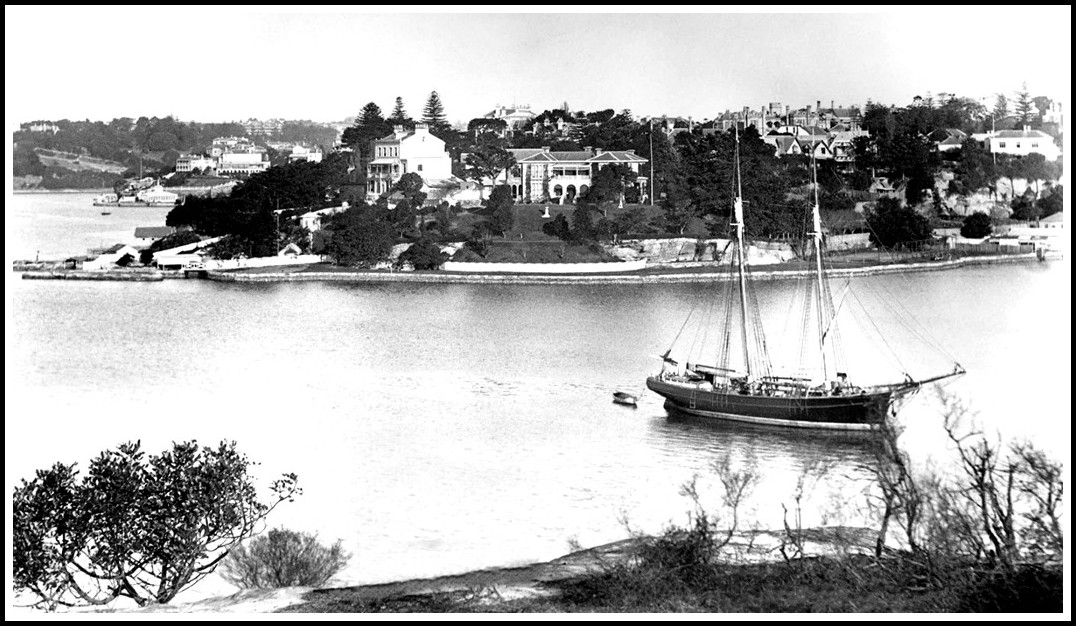

As he was writing Voss, White drew deeply for the first time on the history of his own family. Mr Bonner, patron to the expedition, lives in a house with Lulworth’s dark gardens overlooking a rushy marsh on the edge of the Harbour. There is a bunya bunya on the drive. The house is a wilderness of mahogany and Bonner’s study, like Dick’s [PW’s father’s] room at the end of the veranda, was somewhere all is disposed for work except the owner.

Potts Point (c.1880), a suburb of Sydney, home of the Bonner family

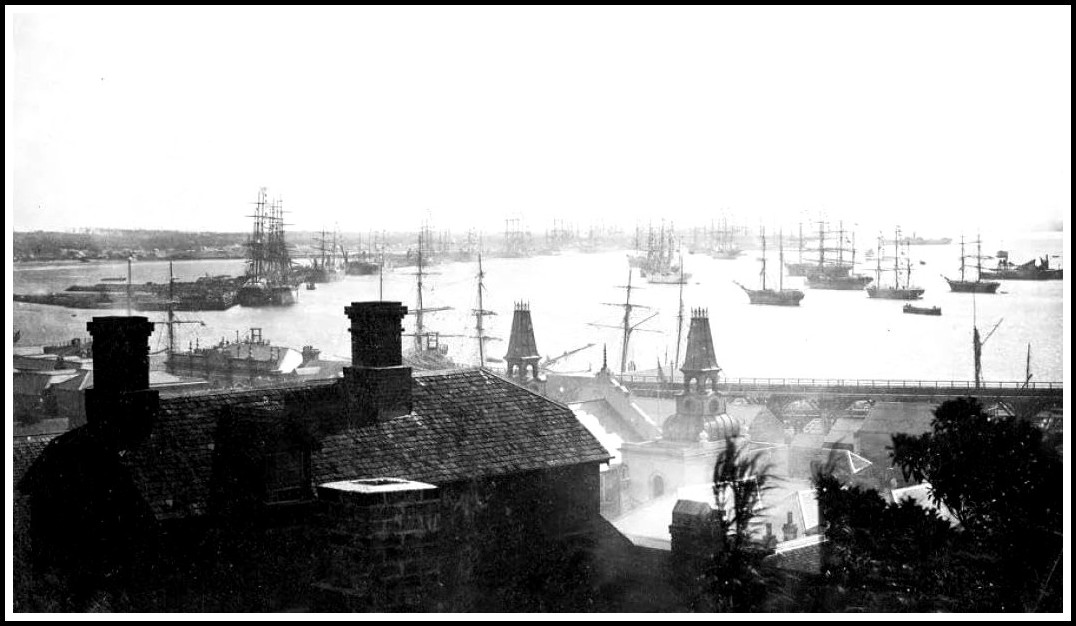

The first stage of Voss’s journey takes the party by sea to Newcastle and overland through the ‘gentle, healing landscape’ of the Hunter to Rhine Towers, a picture of Belltrees1 in the early, more innocent years before the great house was built. In the care of the Sandersons, Rhine Towers is a place of simplicity and perfection, an Eden in the bush. Memories of Belltrees are strong in the book. In the boy’s imagination there was always a connection between the property and explorers. From Belltrees Henry Luke White sent the naturalist Sidney Jackson to unexplored corners of Australia searching for birds and eggs. When White was a boy he was taken to meet Jackson in Sydney and watched him sorting through the skins and corpses of his finds. The Christ-like ornithologist Palfreyman who accompanies Voss is not Sidney Jackson, but the ornithologist and his German leader were conceived by a man with this childhood link to explorers and exploration.

1 – The White family’s huge pastoral estate in the Upper Hunter Valley, NSW.

Newcastle Harbour, Australia, Nineteenth Century

VI. A SENSE OF PLACE | SYDNEY NOLAN

Voss leads the party from that sublime valley to the flat coolabah country of White’s jackerooing days. Jildra is the last outpost before the wilderness. For the portrait of Jildra White drew on his memory of Brenda, the station over the Queensland border to which he had driven with his uncle, where they woke at dawn to the sound of birds and black servants padding about on bare feet. But the squalor of Jildra comes from a half-remembered newspaper story from that time: a story about ‘a real bastard on an isolated station’. West of Jildra lay the desert. White had never seen, never saw, the dead heart of Australia. All he had to draw on were his memories of Africa, and books and paintings. Once the expedition left Jildra, Voss was on an expedition to the outer limits of his imagination.

Patrick White’s jackerooing days: Barwon Vale | A bare hill at Bolaro

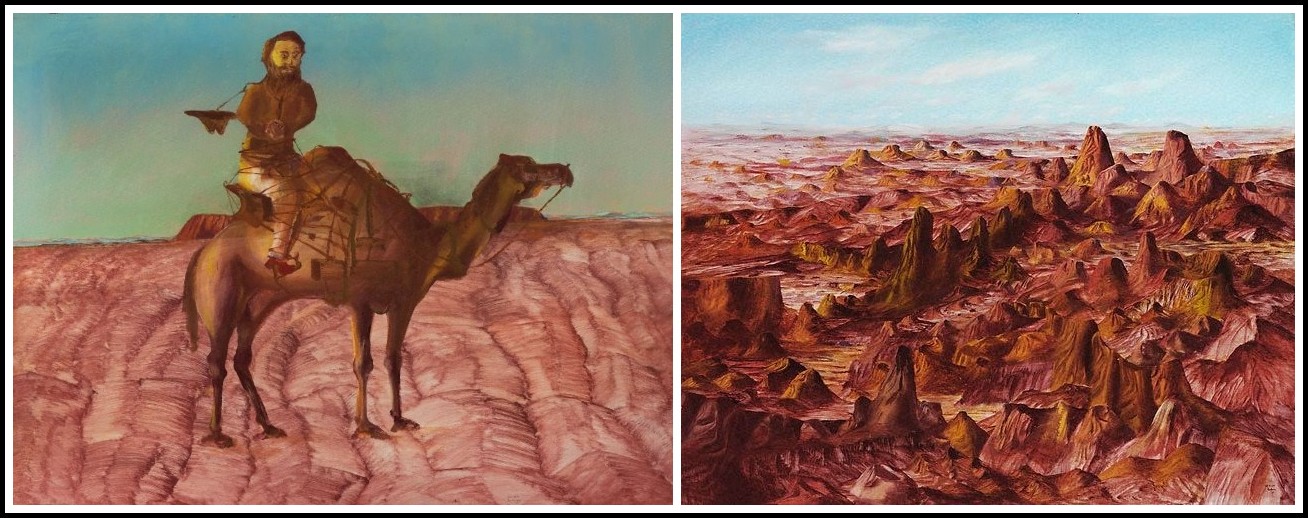

White had a guide. He had seen the great exhibitions of Sidney Nolan’s outback paintings in March 1949 and March 1950. These made Nolan’s name in Australia. When you enter the gallery, wrote the critic of the Sydney Daily Telegraph, the blaze of reddish-brown hits you like a ton or two of real red earth. White came to the Australian desert through Nolan’s eyes.

Sydney Nolan, Burke-Willis expedition, ‘Gray sick’, 1949 | Sydney Nolan, Central Australia, 1950

Nolan had seen the gold mines in Queensland, flown for weeks over the centre in the back seat of a Beechcraft of Connellan’s Mail Services delivering to stations and missions from Alice Springs, travelled through the Gulf country and down the coast to Perth. About the time White was first researching Leichhardt, Nolan was reading the diaries of the doomed explorers Burke and Wills. His paintings of their ludicrous journey to the Gulf were those that particularly stirred White: men and camels tramping across the grey-green country of the Gulf, incongruous historical figures in a hostile landscape. Years after these exhibitions, he told the painter how he felt they had both been exploring the same territory, and expressed what they found in the same way. So he asked Nolan to do the jacket for Voss.

Sydney Nolan, Carron Plains, 1948 | Sydney Nolan, Pretty Polly Mine, 1948

VII. WHITE’S HISTORICAL RESEARCH FOR ‘VOSS’

In his magpie fashion White searched for the historical details he needed for the book. He found accounts of Aboriginal painting and ritual in the Mitchell Library. For life in early Sydney he drew on M. B. Eldershaw’s A House is Built and Ruth Bedford’s Think of Stephen, an account of the family of Sir Alfred Stephen. He was Chief Justice of New South Wales in the 1840s when Voss made his journey into the hinterland. I feel these chronicles are of great importance, White wrote to Bedford. All the data on the early ‘rabble’ is already there, but there is not so much to hand on the more respectable classes. You must help fill the gap.

Aboriginal rock painting | Photo: Ash Jurberg

In the end there was little he took directly from Leichhardt’s papers. White accepted Alec Chisholm’s often mocking attitude to the explorer set out in Strange New World, the book in which White had first discovered Leichhardt nearly ten years before. One detail does come straight from the explorer. White was struck by his description of the great comet which, in Voss, hovers over Laura on Potts Point and the rump of Voss’s party in the desert: that unearthly phenomenon, that quick wanderer, almost transfixed by distance in that immeasurable sky.

Comet C/2006 P1 (McNaught), over Pacific Ocean, 2007 | Photo: S. Deiries/ESO

VIII. THE ROMANCE OF VOSS AND LAURA

The affair of Voss and Laura was the greatest technical challenge White faced in the novel. Though they were not ‘seen to copulate’ their passion was intended as an answer to the passionless life White saw around him in Australia. Intellectual passion seems to me to rise no higher than the snarling of a mongrel pack in the correspondence columns of the fortnightlies and weeklies. As for physical passion, I sense on the one hand sparrow-fucks, and on the other the weekly grind. Surely Voss and Laura were passionate individuals. Nor was the long-distance courtship meant entirely as a literary device, for White believed in such communication of the spirit as a fact. From Cape Cod he had written to Spud Johnson half a continent away in Taos, you have been extraordinarily close. I could almost put out a hand. In his bronchial fevers he had seen the figures of Voss and Laura together, just as they were to meet in their own fevers; and he came to have a guarded belief in the existence of extra-sensory perception: I am continually receiving evidence of it myself.

Julia Margaret Cameron, New Year’s Eve, 1875

IX. LITERARY AND MUSICAL INFLUENCES ON ‘VOSS’

Critics would later spend a good deal of time guessing which writers had influenced White as he worked on Voss. Most of the time, I’m afraid, it leads up the wrong tree. T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets were cited but White had not yet read them, nor The Golden Bough, nor Dante except a little in the translation by Dorothy Sayers. All these were said to have influenced Voss. In correcting these misapprehensions White acknowledged he may have arrived at certain conclusions via other writers who had read these works. He rather regretted not having read some of those whose influence was detected in his work – Andre Malraux, for instance, whose La Condition humaine he had read about twenty years before, when I did not care enough to follow him in his career; Conrad, several books in my teens when I could not understand what all his conflicts were about, and consequently did not like him. (The one Conrad I do like, and which I read just at the end of the War, is Under Western Eyes.) Of Nietzsche I read Also sprach Zarathustra when I was an undergraduate without being drawn to it.

Joseph Conrad, 1904 (Photo: George Charles Beresford) | Joseph Conrad, Under Western Eyes, Penguin Classics

One important influence at the time of Voss was Rimbaud. Frank Le Mesurier, the poet on Voss’s expedition, a man with dark thin lips, dark eyes and proud nose, emerged from White’s passion for Rimbaud. He had grown drunk on the poetry when he first discovered it, and read Enid Starkie’s study of the poet several times. By the time he wrote Voss he was soaked in Rimbaud. Le Mesurier, though he is a comparatively undeveloped character in the novel, just had to be there.

Sydney Nolan, Rimbaud, 1939 | Enid Starkie, Arthur Rimbaud, 1961

White was conscious of being influenced more by music and painting than writing. In the last ten years I think music has taught me a lot about writing, he told Ben Huebsch. That may sound pretentious, and I would not know how to go into it rationally, but I feel that listening constantly to music helps one to develop a book more logically. To get into the mood for work, he played the gramophone until he was ‘quite drunk’ with music. Always something of a frustrated painter, and a composer manqué, I wanted to give my book the textures of music, the sensuousness of paint, to convey through the theme and characters of Voss what Delacroix and Blake might have seen, what Mahler and Liszt might have heard. The music of Mahler meant most to him as he was writing Voss.

Gustav Mahler

Liszt was not a composer he liked much, only that his bravura and a certain formal side helped me in conveying some of the more worldly, superficial passages of Voss. The same with Delacroix. The latter is a painter I admire, but for whom I have no affection. He felt very dose to Alban Berg—an affection strengthened when he discovered Berg was a bronchial asthmatic—and he played Berg’s Violin Concerto all through the ‘illness’ of Laura Trevelyan.

Alban Berg

It took Bartok to finish off the explorer. I couldn’t get the death of Voss right, and I was in bed with bronchitis feeling like death. I suddenly got out and put on the Bartok Violin Concerto, and everything began to come right. I suppose there was not much connection between that scene and the concerto, but it liberated me.

Béla Bartók

DAVID MARR: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments