Jean Nouvel

JEAN NOUVEL ON ARCHITECTURE & DESIGN

From Jean Nouvel, Architecture and Design 1976-1995 (Milan: Skira Editore, 1997) pp. 11-15.

The text, translated by Francisca Garvie, is the opening of a talk Jean Nouvel gave in Milan in April 1995. The majority of the images are from Ateliers Jean Nouvel.

I. JEAN NOUVEL: MY APPROACH TO TECHNIQUE

I am often presented as an architect of ‘French high tech.’ I would like to begin by explaining what I mean by the term modernity:

– Modernity is alive, it is not some historical movement that was interrupted a few decades ago.

– Modernity is making the best use of our memory and moving ahead as fast as we can in terms of development.

That is why although I recognize that what is called the ‘high tech’ movement occupied an important place in the seventies, I think that if we entered a new building today and our main impression was, ‘Oh what a lovely beam!’, that building would be conveying a weak message.

Fondation Cartier | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 1987

Technique must serve an emotion or a symbol. In today’s modernity, what takes priority is the aesthetic of the miracle. That is to say we require maximum performance but at the same time have no desire to know how it is achieved. Everything is becoming increasingly simple and increasingly complex, increasingly light and increasingly compact. Everything is being miniaturized, mechanized. In the field of computers, miniaturization now happens on an incredible scale and at an incredible speed. Materials and techniques are evolving at a spectacular rate. Glass is one example: at the press of a button a sheet of glass can become translucent, opaque, coloured. Soon we will be able to create energy by the passage of light through glass, which means for us architects that we will be able to heat precisely those areas where the heat loss used to be greatest. All this is a matter of technique, but of technique to be used in a natural way.

100 11th Avenue, New York | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 2012-18

This century has indeed seen amazing technical developments and man has been fascinated by what the machine can do. One of the first to examine the relationship between machines and architecture was Le Corbusier, which only goes to show that this fascination with the aesthetic of the machine is not new. And it was only logical for the Archigram group to transform it into a poetry of the machine by extrapolating the technical aesthetic of this century. But modernity is alive. It has shifted towards other areas that have little to do with the expression of structural truth. All these buildings that look like carapaces, the high tech buildings that reflect this approach, must today be regarded as the architectural expression of an era, as historical architecture, in the same way as we regard the flowering of technology in the 19th century.

Guthrie Theater, Minneapolis | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 2001-06

So much for my approach to technique. I use state-of-the art techniques when I find it useful. But as I have of-ten said, it would never occur to me to write a book using only the words invented in the last twenty years. I think it is more interesting to show the relationship between new elements of vocabulary and older, more archaic words as a means of imbuing them with their full meaning, their synergy, their dynamism.

One Central Park, Sydney | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 2008-14

In that sense my architecture may be described as modern and contemporary. I have already rejected the high tech label. I also refuse to be called postmodern insofar as that term has historicist connotations in architecture and nothing horrifies me more than some of the architecture of the past twenty or thirty years, which is nothing but reproduction, the product of a bad academic approach that recycled old forms without knowing how to do so and thereby weakened its own models. The historical town, the town one loves and which can be read like a book of stone, is made up of successive strata of modernity. We cannot refuse to add our own. It is indeed our responsibility to continue constructing it. We cannot economize with the culture of an era.

One New Change, London | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 2003-10

II. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN

For me, the question of the relationship between architecture and design is a question of limits, of boundaries and of the links that can exist between disciplines. There are fundamental differences between architecture and design. The first is the fact that architecture is unique and can only be specific, whereas design is the creation of multiples aimed at a multitude of individuals. The second is that architecture must convey a sense of the present; it will be up to future generations and the buildings that will be constructed around them whether or not it remains meaningful. In the case of design, the reverse is true: design will be situated in different contexts, surrounded by objects unknown to it. It will pass down through decades, centuries even, and be regarded as the trace of one culture among many. The environment changes: in both cases we see the evidence and the petrification of a form of culture. In the case of architecture, the object is static. In the case of design, the object moves in space and time.

Fondazione Alda Fendi, Rome | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 2012-18

There is a kind of contradiction or paradox in my case: I do not draw as an architect or as a designer. Or very rarely so. I often draw a parallel between the architect and the film producer for I believe their situations are similar. They both have to produce objects by teamwork. They have to enter into a reality which is that of their time, whatever the constraints. There is a kind of compromise here which the artist, in the strict sense of the term, be he composer, painter or writer, does not have to face.

Renaissance Barcelona Fira Hotel, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 2005-12

The architect is concerned with what is real. I approach this reality by using words, concepts and of course from time to time a few scrawls. But I do not do so through drawing or what I would call the ‘intuition of the pencil’. Whether a project is architecture or design, it develops through ‘brain storms,’ exchanges, objective argument and external analysis. I believe in this need for more profound analysis.

European Patents Office, The Hague | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 2012-18

Moreover, in the case of design we are not condemned to redesign everything. Some objects do not lend themselves to being redesigned. Either because techniques have not evolved or because methods, customs and attitudes have not evolved. The designer does not have to systematically renew objects. Conversely, the moment new techniques, new materials, new methods, new attitudes, new programmes appear, the designer is there. And sometimes new environments linked to architectural frameworks are there too.

Ycone, Lyon | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 2012-19

III. JEAN NOUVEL ON THE INSTITUT DU MONDE ARABE

I will now comment on the Institut du Monde project and try to pose the question of the relationship between architecture and design. I do not presume to answer it in full. I myself came to design by chance and by necessity. By chance because for some of the buildings I constructed I was also asked to design an armchair, a bed or a storage unit. And by necessity because it sometimes happened that for a given space I could not find the object that would enable me to reply to the question it put.

Institut du Monde Arabe | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 1981-87 | Photo: © IMA / Fabrice Cateloy

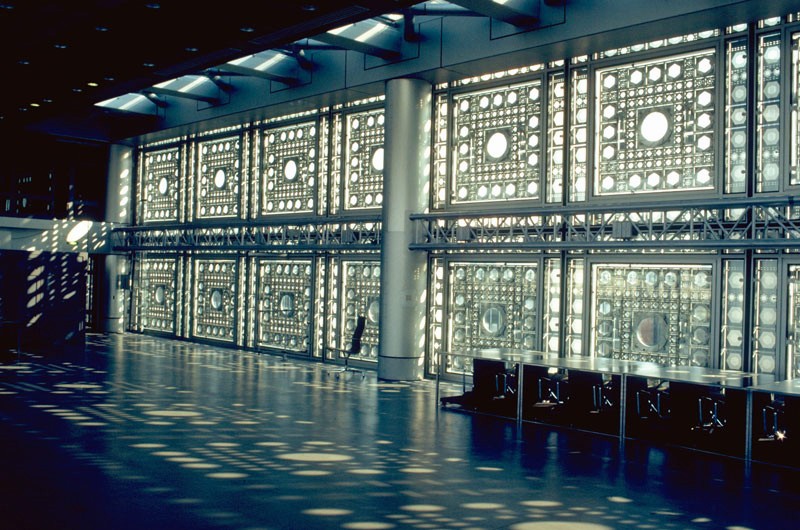

I began to consider the question of light at the Institut du Monde Arabe. The theme of the moucharabieh or Arab screen is the perforation of a wall by light. This is designed to protect against the climate but is also specific to Arab culture: the wind blows through and women can look out without being seen. True, the problem was different in Paris, where the light is less strong and women do not need to hide themselves. But we wanted to distance ourselves somewhat from the nearby Jussieu University.

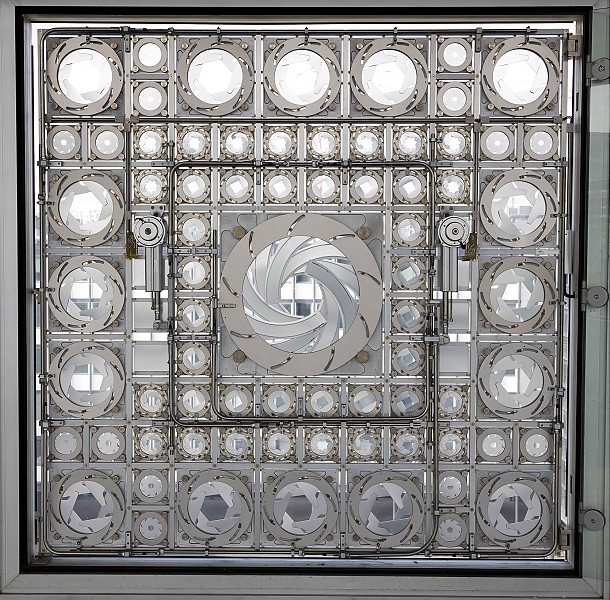

Arab screen, Institut du Monde Arabe | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 1981-87

Taking up the themes of geometry and light again, I opted to make the southern facade a wall consisting entirely of camera shutters, so as to create a variable geometry of circles and different kinds of polygons that allowed exactly the required amount of light to penetrate in summer and winter. There are 25,000 camera shutters run by 250 motors linked up to a central computer which decides whether to open or close them depending on the intensity of the outside light. The change of aperture is almost imperceptible, which made some people say the system did not work.

Arab screen, Institut du Monde Arabe | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 1981-87

To respond to the sophisticated design of the Arab screens set at intervals in wood and marble, we designed a mechanism inserted between two layers of glass that operates with the delicacy of clockwork, like a grandfather clock. It took two years to perfect the prototype: this was a real design problem, both technically and in terms of manufacture and attention to detail. The ultimate aim was to obtain a specific quality of light. The client, for his part, wondered whether Venetian blinds would not do the same. The theme of light is also reflected in the stacking of the stairs, the blurring of contours, the reflections and shadows, the superimpositions. I felt that the north facade, which is not exposed to changes of light, lacked relief, so I attached a silkscreen to it depicting a rather abstract skyline.

Institut du Monde Arabe | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 1981-87

We designed the showcases and modular furniture for the museum. In the case of the auditorium, which had a very small budget, we sought out Renault-25 seats, which give the impression that the empty room is peopled by extra-terrestrials. The children’s corner was conceived in Oriental colours and motifs. The patio forms the centre of the building, the symbolic centre of Arab culture. It was equipped with a mercury-like fountain. It is framed by walls made of plaques of thin white marble which create the effect of alabaster and diffuse a pale and almost magical light.

Patio, Institut du Monde Arabe | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 1981-87

THE INSTITUT DU MONDE ARABE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 14

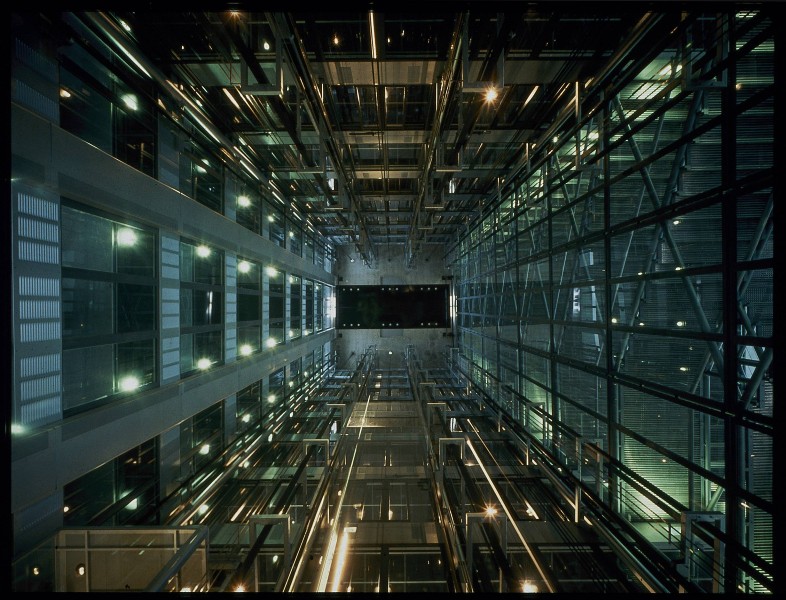

Underfoot, overhead, left, right, behind, ahead: Omnipresent, metal and glass conspire to remove all our bearings; unmoored, we ascend in spidery space. In a riot of shadow and light the guts of the construction invade our vision; reaching for your hand I catch your gaze: In the depths of your eyes as our hands entwine, I see Winston and Julia about to commit sexcrime.

Institut du Monde Arabe | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 1981-87

Daylight ! We cross a footbridge and step onto the rooftop terrace. Look! Towering above the other buildings, the Ministry of Truth—or is it the Ministry of Love? Préfecture de Paris, Temple du Marais, Ile Saint-Louis, Notre-Dame.

Across the Seine from the terrace of the Institut du Monde Arabe

̶ Sprague!

I take the hand you hold out to me; we cross the terrace and penetrate into the interior space. Glass walls, polished floors; glowing columns, gleaming doors: Refracting, reflecting, surfaces shimmer with patterns of filtered light. And then it appears, a giant screen of geometric forms, a riot of proliferating motifs: Intensely patterned panes unfold their symmetry. Look! Mirror-plates in meticulous rhythm, flashes of prudence and vanity; clockwork in crystal panels, wheels of time and fortune.

̶ Come!

You take my hand, and through filigreed light lead me.

Institut du Monde Arabe | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 1981-87

On the rooftop, in the corridor between the empty restaurant and the Seine façade of the building, cubic modules of wicker furniture stack up in disorderly columns. Bearing witness to winter, Arabic urns of barren earth punctuate the passage. We slip in between two stacks of chairs and wend our way to the railing. Spinning around, you say:

̶ Take off your coat.

In the dark groves of your eyes sulphur butterflies swarm; ready to do what must be done, I shake my jacket from my shoulders and toss it onto a railing post. You slip off yours and sling it over mine. Turning your back to the garde-fou, you pull me towards you.

Institut du Monde Arabe | Ateliers Jean Nouvel, 1981-87