KILL BILL & DEATH PROOF

Quentin Tarantino, 2003-04 | 2007

Gérard Wajcman on ‘Death Proof’ and ‘Kill Bill’ (Quentin Tarantino)

‘DEATH PROOF’ AND ‘KILL BILL’ AS EXEMPLARS OF MODERN FETISHISM

Gérard Wajcman, Lacanian psychoanalyst, is a member of the Ecole de la cause freudienne (Paris)

From Gérard Wajcman, ‘Girl talk: Du fétichisme moderne’ (La Cause du Désir, 2012-2 N° 81) pp. 139-145, with a brief passage from Gérard Wajcman, ‘Louise Bourgeois, l’issue comique de la psychanalyse’ (La Cause freudienne 2008/2 N° 69) p. 229. Condensed and translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Uma Thurman, Kill Bill: Volume 2, Quentin Tarantino

I. INTRODUCTION: GIRL-AS-FETISH → GIRL-AS-FETISHIST

Since Antiquity, the arts have been represented by women. Not just any women: imagining a tall blonde or a petite brunette symbolizing dance or music wouldn’t seem quite right. No, the arts are represented by the Muses, the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne. Since Plato, the Muses have been nine in number. Song and eloquence each have a Muse, but an art like painting, bizarrely, does not. Nor does cinema, despite its status (at least in France and Italy) as the seventh art.

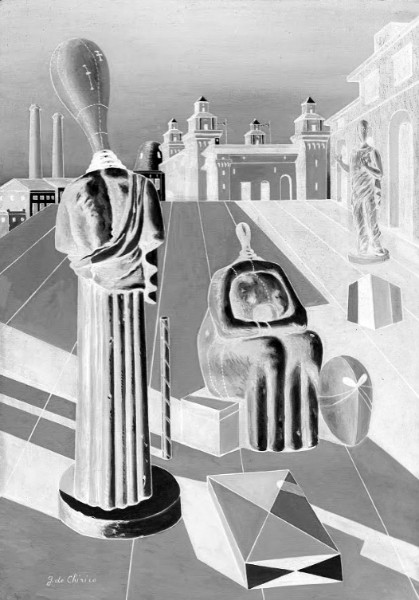

Giorgio de Chirico, The Disquieting Muses, 1916

Be that as it may, the belief is widespread that, unlike painting, cinema has its muses. However, in contrast to the inspiring muses who remain in the artist’s shadow, in cinema the muses appear onscreen. And thus it is that women are at once a cause and an object of cinema.

Marlene Dietrich & Josef von Sternberg | Anna Karina & Jean-Luc Godard | Hannah Schygulla & Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Cinema is an art that is inherently fetishistic. Even if our world with its plethora of objects is a gigantic invitation to debauchery, nothing new, in terms of perversion, can be discerned on the horizon. Except, perhaps, this question that seems to be crystallizing today: Is not the girl-as-fetish of yesteryear becoming the new fetishist? Cinema, and especially the clinical eye of Tarantino, invites us to examine the question more closely.

Photo courtesy of freestocks

What we learn from Death Proof is that women in cinema are not simple objects but causal agents. As causal agents, their primary effect is to provoke speech. Since they themselves speak, they are speakers who provoke speech.

Jordan Ladd, Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

Terminological Note 1

JOUISSANCE: EVERY DRIVE IS A DEATH DRIVE

Dylan Evans

Abbreviated from Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (Routledge, 2001) pp. 91-92

As Gérard Wajcman makes frequent use of the untranslatable Lacanian term jouissance in the rest of his essay, I interpolate here the most useful elements from the definition of the term given by Dylan Evans in his Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis. In some instances of Wajcman’s essay, the term is to be understood in all its Lacanian richness; in other instances, it is enough to supply ‘come’, get off’ or ‘orgasm’ to render the intended meaning. R.J.

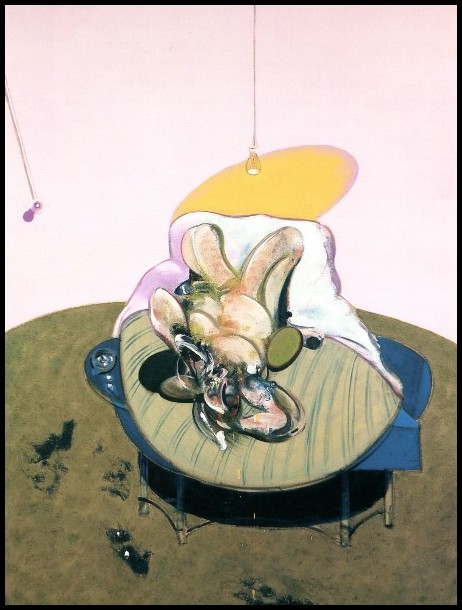

Francis Bacon, Lying Figure, 1969

The pleasure principle functions as a limit to enjoyment; it is a law which commands the subject to ‘enjoy as little as possible’. At the same time, the subject constantly attempts to transgress the prohibitions imposed on his enjoyment, to go ‘beyond the pleasure principle’. However, the result of transgressing the pleasure principle is not more pleasure, but pain, since there is only a certain amount of pleasure that the subject can bear. Beyond this limit, pleasure becomes pain, and this ‘painful pleasure’ is what Lacan calls jouissance; ‘jouissance is suffering’. The term jouissance thus nicely expresses the paradoxical satisfaction that the subject derives from his symptom, or, to put it another way, the suffering that he derives from his own satisfaction.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647–1652 (detail)

The very prohibition of jouissance (inherent in the symbolic structure of language and in the Oedipus complex/the incest taboo) creates the desire to transgress it, and jouissance is therefore fundamentally transgressive. The death drive is the name given to that constant desire in the subject to break through the pleasure principle towards the thing and a certain excess jouissance; thus jouissance is ‘the path towards death’. Insofar as the drives are attempts to break through the pleasure principle in search of jouissance, every drive is a death drive.

Gustave Moreau, Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1864

There are strong affinities between Lacan’s concept of jouissance and Freud’s concept of the libido, as is clear from Lacan’s description of jouissance as a ‘bodily substance’. In keeping with Freud’s assertion that there is only one libido, which is masculine, Lacan states that jouissance is essentially phallic; ‘Jouissance, insofar as it is sexual, is phallic, which means that it does not relate to the Other as such’. However, in 1973 Lacan admits that there is a specifically feminine jouissance, a ‘supplementary jouissance’ which is ‘beyond the phallus’, a jouissance of the Other. This feminine jouissance is ineffable, for women experience it but know nothing about it.

Brassaï, Phénomène de l’extase, c.1933

II. TARANTINO: FILMMAKER OF THE JOUISSANCE OF CHATTER

In Death Proof, Tarantino films ‘girl talk’. The movie’s stuntwomen are stuntwomen of speech. Their talk has the status of action, but not in the sense of Austin’s performative utterances and speech act theory: Tarantino doesn’t give a damn for acting on the real with words. In his filmic universe, one acts on the real with guns or swords. Talking does not replace fighting. Speech is a body-act. It is an eruption of the body.

Sydney Poitier, Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

Lacan spoke of the jouissance of chatter. Tarantino is the cinéaste of this jouissance. For him, the founding utterance is not ‘to speak is to do’ but ‘to speak is to come’. And so the women in Death Proof raise a question: ‘Is talking about sex just as good as sex?’. Words can make you come, but they cannot express jouissance. That is why words are abundant in Tarantino’s cinema: One talks all the more, in his films, because words cannot reach what they are aiming at.

Vanessa Ferlito & Sydney Poitier, Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

And that is why in Death Proof, girl talk pushes towards ever greater sexual detail:

– How about enlightening us on what it is you did do?

– Nothing to write home about. We just made out on the couch for about twenty minutes.

– Dressed, half-dressed, or naked?

– Dressed. I said we made out. We didn’t do ‘the thing’.

– Excuse me for living, but what is ‘the thing’?

– You know, it’s everything but.

– They call that ‘the thing’?

– I call it ‘the thing’.

– Do guys like ‘the thing’?

– They like it better than ‘no-thing’.

– Were you making out sitting up or lying down?

– We started sitting up, we worked our way to lying down.

– The plot thickens. Who was on top?

– I was straddling him.

Then the girl says she asked the guy to leave, he started whining, so she kicked him out. The girls laugh. And there you have it: Guys are what girls talk and laugh about.

Vanessa Ferlito, Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

III. GIRL TALK AND FOOT MASSAGE

Girl talk exists, guy talk doesn’t. That’s a decisive difference. Girls find jouissance in talking, while guys don’t. In Pulp Fiction there’s a scene where John Travolta, by inadvertence, kills a guy while talking to him. Call it ‘crime by slip of the tongue’—the slip that kills. For guys, the act drowns the word; for girls, words do the drowning.

John Travolta, Pulp Fiction, Quentin Tarantino

And Pulp Fiction shows us a third way: Samuel Jackson, who miraculously escaped death, lays down his gun and becomes a monk, devoting himself to Scripture. He renounces bodily jouissance, even if it is for death. His conversion to the Word, his choice of word over act, is a castration. Compare that to the women of Death Proof: They renounce nothing—neither word, nor act, nor body, nor death. And they go further: renouncing no species of jouissance, they even try to invent new ones.

Zoë Bell, Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

So, in Pulp Fiction, besides killing with a gun, guys pursue jouissance via the fetishistic act of the foot massage—but only in words, for it’s talked about but never seen performed.

Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

IV. FETISHISM IN THE FEMININE

Tarantino’s films fall precisely between the two poles that, for Lacan, keep jouissance in tension: ‘It begins with a little tickle and ends in a blaze of gasoline’. So said Lacan, in Seminar VII, sounding awfully like Tarantino. Consider Kill Bill, which could be subtitled ‘Make way for the women!’. In the film, in effect, all guys are called Bill. Uma Thurman kills David Carradine using the secret ‘five-point palm exploding-heart technique’. And so the hero of the 1970s is defeated by the heroine of the new century. Kill Bill announces that heroines are the new heroes—and the new perverts.

Uma Thurman, Kill Bill: Volume 2, Quentin Tarantino

Tarantino himself is clearly a polymorphous pervert. Girls feet, that’s what gets him off. Right from the opening credits of Death Proof, we see a woman’s feet, toenails lacquered red, propped up on the dashboard of a car. This, clearly, is for the guys’ delectation: girls don’t go in for foot fetishism. ‘Talk massage’ is their thing. Tarantino, like Hitchcock, is aware of his perversion (he knows where his desire lies); again like Hitchcock, he films women he likes just as he likes but, unlike Hitchcock—and this, in part, is why he is an important filmmaker—he goes on to ask the question: ‘What gets women off?’.

Tippi Hedren, The Birds, Alfred Hitchcock

Indeed, what is a girl’s greatest pleasure? In Death Proof, it is talk. And guys. And cars. Making a fetish of cars is usually a guy thing. So girls are now taking over guys’ perversions. That’s the story the film tells. It’s rare that women are fetishists, since women are well-placed to know what they lack.

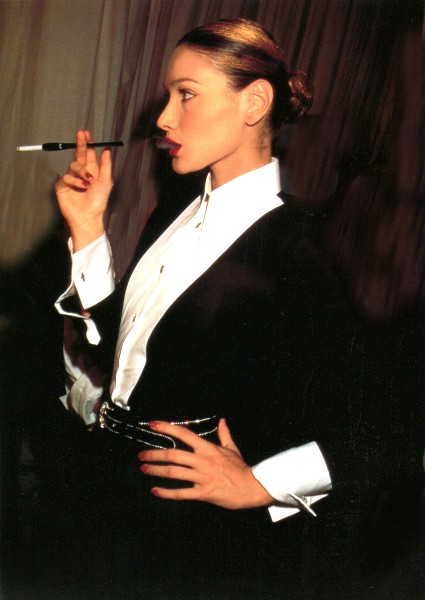

Carla Bruni, Dolce and Gabbana, 1994

And yet, whether girl or guy, we are all immersed in a generalized, industrialized fetishism. Freud explained how objects circulate by metonymy, as substitutes for the maternal phallus, ‘something’ taking the place of ‘nothing’. Today, in a world drowning in objects, we have reason to wonder whether the clinical treatment of fetishism is still relevant. Indeed, all the world’s a market now, and all men and women mere consumers. Condemned to consume, we have made fetishism a new social norm.

Sylvie Fleury, Agent Provocateur, 1995 | Art Club 2000, Gap, 1993

Terminological Note 2

THE STRUCTURE OF ‘NORMAL’ MASCULINE FETISHISM

Geneviève Morel

From Geneviève Morel, ‘Filles fétiches, femmes fétichistes’ (Savoirs et clinique, 2009/1 n° 10) page 12. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

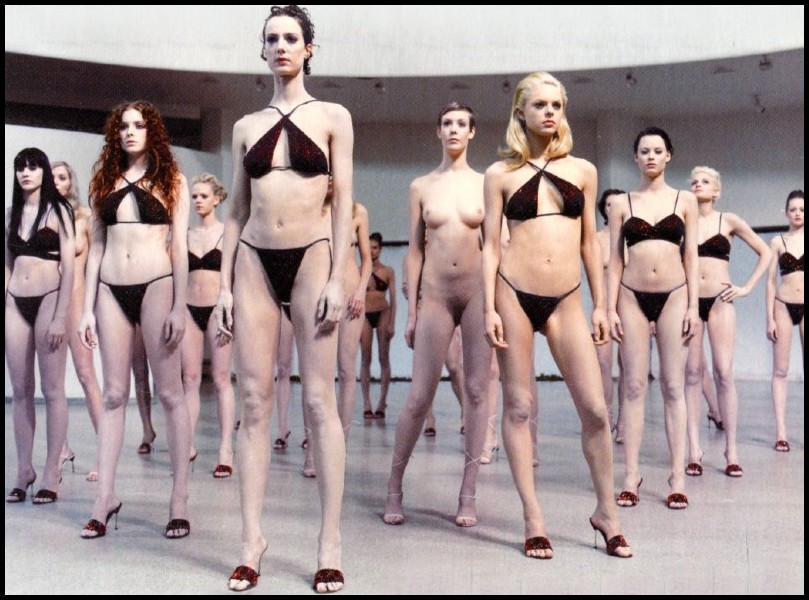

Vanessa Beecroft, Show, 2001

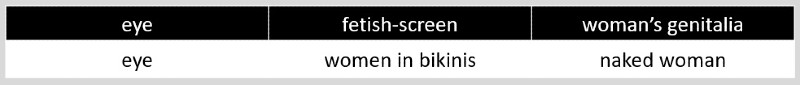

This image from a Vanessa Beecroft ‘tableau vivant’ represents quite accurately the structure of ‘normal’ masculine fetishism as defined by psychoanalysis. In its simplest expression, it consists in an eye-subject, in front of it a woman’s pubic triangle, and between the two, a screen. The fetish is projected onto the screen, and enables the eye-subject to hide the woman’s naked genitalia from its view, to veil it.

It’s a little more complicated than that, but hardly more. One becomes a fetishist when one decides that a woman’s genitalia (usually the mother’s), where one has noticed there is no penis, has one anyway. But this penis that has never existed, this object that is defined only by its absence (since, and with good reason, one has never seen it) is in fact a symbolic object that lacks the phallus, there where one, in a fictional world well-ordered by our desires, would expect to see it. In no way, then, is it the penis we are referring to, even if, for convenience, we often call it that. The fetish, Freud says, is the ‘monument’ one builds to maintain, despite everything, this dual belief, which he calls ‘denial of castration’.

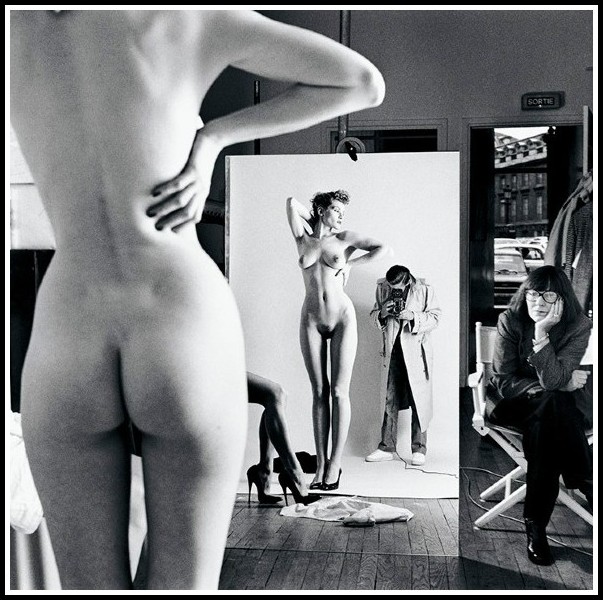

Helmut Newton, Self-Portrait with Wife and Models, Paris, 1981

V. EMBODYING THE FEMININE ZEITGEIST

Cinema has been inclined, when it comes to grappling with this new ‘clinic of the object’, to focus on women. Not surprising, since it has always been remarkable at building paradigms, at making women ‘models’. Cinema, indeed, is the only art where the feminine Zeitgeist can crystallize overnight, as it were, in one woman. In the sixties, when we finally turned the page on the post-war years, it was Brigitte Bardot who embodied the spirit of the new woman; it was she who heralded the age of objects, of unrestrained jouissance, of a new freedom for women. She appeared in 1956, in Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman, well ahead of the New Wave.

Brigitte Bardot, And God Created Woman, Roger Vadim

The two—New Wave and New Woman—would come together in 1963 in Godard’s Contempt. Camille, the new woman, is not only a new image, a woman beautiful and free, but also a woman who despises a man. Moravia’s novel came first, of course, but literature alone couldn’t create this figure—what was needed was incarnation, and Bardot perfectly fit the bill. Now, if a New Woman is a woman who shows us a new way to find jouissance, where, then, is the woman who embodies today’s Zeitgeist?

Brigitte Bardot, Contempt, Jean-Luc Godard

Each New Woman, as she embodies the Zeitgeist, embodies Freud’s classic question: ‘What does a woman want?’. Indeed, for Freud, that was the question, and as such we may assume that, to his mind, it would remain forever unanswered. If so, what is eternal in the Eternal Feminine is that women perpetually raise this question in men. The power of the New Woman, seen in cinema as a ‘symptom of the times’, lies in the fact that she embodies this question at a given historical moment. An enigma, the question carries a certain menace for men, since knowing what a woman wants now implies changes in what is expected of them. That is what Godard explored in Contempt. And today, what does a woman expect of a man? Let’s see what Tarantino shows us in Kill Bill.

Uma Thurman, Kill Bill: Volume 1, Quentin Tarantino

Kill Bill is the story of a woman in leather who rides a motorbike and wields a sword in her quest for revenge. She is the figure of the New Woman. Tarantino, for his part, wields his own weapon: Uma Thurman. She is the embodiment of the New Woman today. Confronted with this hypermodern weapon (the Bride), all men are called Bill. They’re not bastards, just disarmed men. And thus a new figure of a man comes into focus: a man at the service of a woman’s jouissance.

Uma Thurman, Kill Bill: Volume 1, Quentin Tarantino

In Kill Bill, the heroine was still expecting something…

Uma Thurman, Kill Bill: Volume 1, Quentin Tarantino

… in Death Proof, the heroines no longer expect anything. ‘Yes’ or ‘No’, ‘Come here’ or ‘Get lost’—that’s what they tell the men. The women have the upper hand. Indeed, all that a woman wants from a man is what Arlene tells Nate: ‘You got two jobs: Kiss good and make sure my hair don’t get wet’. The man no longer carries a sword. Instead, he holds an umbrella.

Omar Doom, Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

VI. HYPERMODERN ECSTASY AND THE DESACRALIZED FETISH

We are in the age of the sex toy, an object of jouissance reserved largely for women. It makes them come and it makes them laugh. A guy can become nothing but a living sex toy. That’s why Stuntman Mike is yesterday’s model: ‘Fucking cut himself falling out of his time machine’. He would neither make women come nor make them laugh: He would frighten them. Not anymore. For the women of today, he’s just a deadbeat, no living sex toy.

Kurt Russell, Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

In this utilitarian scheme of things, a car and a guy are pretty much the same thing. With, of course, a clear advantage for the car: it kisses better. Yes, that’s what the film shows: no man can be as good a kisser as a Dodge Challenger 1970 with a 440 engine. And girls will go to great lengths to get one.

Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

Tarantino shows Zoë Bell, a stuntwoman playing herself, stretched out on the hood of a car tearing along a road at 95 mph.

Zoë Bell, Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

That’s hypermodern ecstasy, hand-to-hand combat between woman and machine; that’s sex dispensing with man and bed, sex à la Saint Teresa: ‘I saw in his hand a long spear of gold, and at the iron’s point there seemed to be a little fire. He appeared to me to be thrusting it at times into my heart, and to pierce my very entrails; when he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out also, and to leave me all on fire with a great love of God. The pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it. The soul is satisfied now with nothing less than God.’ Tarantino’s spear of gold comes from a Detroit factory; his weapon on wheels is an entirely desacralized fetish.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647–1652 (detail)

Women may like cars, but instead of taking them seriously, as men do, they play with them. And that takes us to the heart of the matter: Women know the truth of semblances, they know that all that glitters isn’t gold. Indeed, they do with the phallus as they do with all shiny objects: they wear it as an ornament. Women are not ashamed of sham precisely because they see through it. In contrast, as Louise Bourgeois said, ‘Men cannot lie, and that’s why they’re so likeable’. Or, as Mae West, dancing cheek-to-cheek, asked her partner: ‘Do you have a revolver in your pocket, or are you just happy to see me?’ In all women a killer fetish lies sleeping.

Kate Moss, John Galliano, 1994

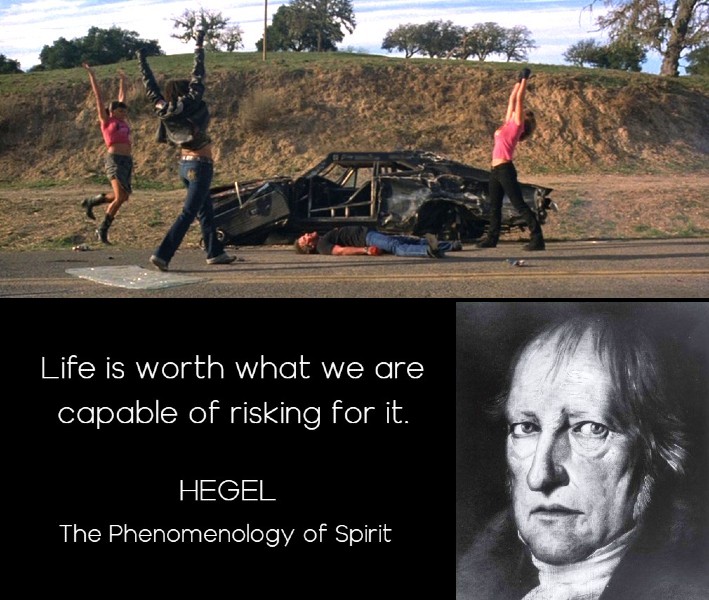

From a Hegelian perspective, this is a story of the end of servitude. If men have dominated women, freedom is won simply by showing that there are girls in flip-flops capable of overcoming fear and braving death. ‘Life is worth what we are capable of risking for it’, wrote Hegel in The Phenomenology of Spirit. By this standard, the women of Death Proof are truly alive. Indeed, they are death proof.

Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

The killing of Stuntman Mike is also the killing of the fetish, an old fetish in a leather jacket and cowboy boots who drives a fast car. Death Proof is the story of fetishes that become killer fetishes.

Zoë Bell, Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

When one looks at these bands of girls in flip-flops, I wonder what guy wouldn’t wish to be transformed into a 1970 Dodge Challenger with a 440 engine. Even if he knows now what flip-flops may hide.

Zoë Bell, Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino

‘KILL BILL’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 10: Bettina

In her room overlooking the sea, she sitting on the bed and I in an armchair, we continued talking cinema.

Uma Thurman, Kill Bill: Volume 2, Quentin Tarantino

̶ Say, she asked me, have you seen Kill Bill?

̶ Yes. One and two.

̶ Did you like it?

̶ Very much.

̶ That film threw me right back into my childhood!

̶ You were a ruthless killer, a girl hellbent on vengeance?

̶ Yes! I went to Lycée Saint-Louis de Gonzague. I was a débutante in a couturier dress and strapless bra. Went skiing in Gstaad. Hung out with a horde of cousins in Biarritz and Deauville.

̶ I see. You were a deprived child?

̶ Exactly!

Uma Thurman, Kill Bill: Volume 2, Quentin Tarantino

The camber of her cheekbones, the arch of her eyebrows; the curve of her nostrils, the cut of her lips—a face of chiselled purity, serene and luminous.

̶ And how does Kill Bill come into it?

̶ Fantasy, Sprague. When I tried to figure out why I found this film such fun, I realized the Bride is everything I was in my adolescent imagination. To transgress freely, to be relieved of morality—that’s jubilation to a girl!

Subtlety and excess, intimacy and aloofness—beguiling, her beauty.

Uma Thurman, Kill Bill: Volume 2, Quentin Tarantino

She continues:

̶ And her determination! That really moved me. That implacable will, drawn from her deepest self. The dignity and grace of her isolation.

̶ Her control of emotion?

̶ Yes, that’s part of it. The pitiless killing of Vernita Green. Her faithfulness to herself. Her vigilance—never lets her traumas return to defeat her. That’s what makes her touching.

I don’t want a somnambulist; she doesn’t want a supplicant: Is that why I feel her blood in my heartbeat? I say:

̶ Amazing, isn’t it, how a film with no obligations to reality can reflect reality so well?

̶ Yes. It’s pure cinema. It struck a chord in me, as a girl.

Kill Bill: Volume 2, Quentin Tarantino

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

Ken Garner on the Music of ‘Kill Bill’

‘KILL BILL, VOLS. 1 & 2’: ALLUSION, INCONSISTENCY, AND ARPEGGIOS

Ken Garner, professor at Glasgow Caledonian University, is also an author and journalist.

From Ken Garner, ‘You’ve heard this one before: Quentin Tarantino’s scoring practices from Kill Bill to Inglourious Basterds’ in Arved Ashby, editor, Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV (OUP USA, 2013) pp. 167-170

The soundtracks of Kill Bill, Vols. 1 and 2 appear on the surface to demonstrate little consistency of musical selection, scoring, or effect. The effective main theme of Vol. 1—Nancy Sinatra’s ‘Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)’ is neither substantively repeated nor, at least until the end titles, has its musical style echoed in any other selections. (Strange’s four-bar solo guitar intro is heard again briefly just once when the Bride arrives at Hands noodle bar on Okinawa.)

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE TRACKS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT,

WHICH COMES FOR FREE.

The only connection it has with the music heard during the main action—a tenuous connection, it must be said—is with Gheorghe Zamfir’s ‘The Lonely Shepherd,’ heard repeatedly later. ‘Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)’ and ‘The Lonely Shepherd’ are both cult vinyl classics, whether as an LP track (Sinatra) or a 45-rpm single (Zamfir). Each has a clear mood of lament—at least in a conventionally musicological, western sense—with a slow solo melodic ‘voice’ in the minor key, whether vocal or instrumental, and the opening accompaniment centered on an arpeggiated figure on guitar. Zamfir is accompanied by the James Last Orchestra, whose trademark precision trumpet section arrangements feature prominently as the song builds. Both songs stand for the Bride, the plaintive solo lead voice/instrument accompanying her story at key moments to emphasize her isolation and lonely quest, be it her would-be execution, her acquisition of the Hanza sword, or her updating the execution list on her flight home at the end, and over the end titles.

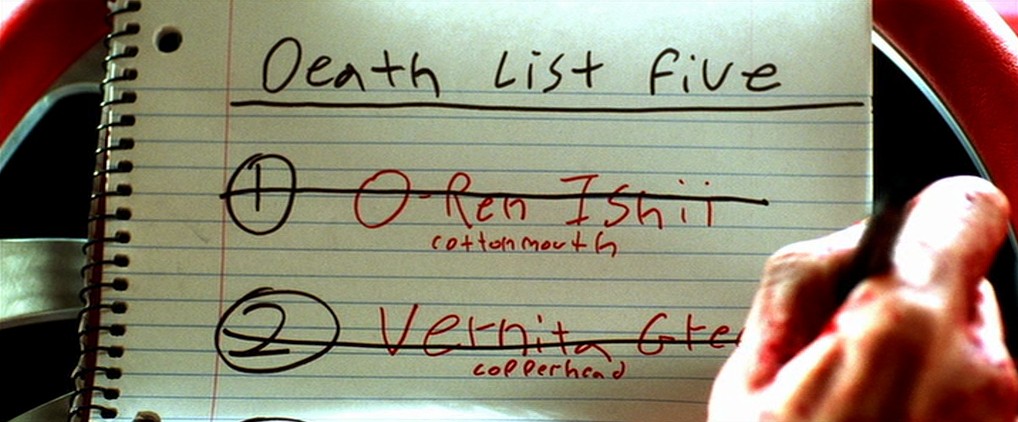

But a further, subtle musical connection might link Tarantino’s deployment of these two records with his use of two famous Japanese vocal film themes, both sung by the actress Meiko Kaji, over the film’s conclusion. Playing over the final defeat and death of Ishii at the Bride’s hands in the snow-covered roof garden is ‘Shura No Hana’ or ‘The Flower of Carnage,’ the theme song from the 1973 female revenge thriller Lady Snowblood—the plot of which clearly inspired the Manga backstory for Tarantino’s Oren Ishii character.

Meiko Kaji, Lady Snowblood, 1973

And then we hear ‘Urami-Bushi,’ the theme song from the Sasori women’s prison films from 1972-73, following the reprise of Zamfir over the end credits. Both songs are again ballads in the minor key, here in 6/8 rhythm, with the solo female voice accompanied prominently by an arpeggiated figure played on acoustic guitar with orchestra and counterpointed with melodic lines played either on the panpipes (‘Shura No liana’) or trumpet (‘Urami-Bushi’). The latter also features prominently in an accompanying reverberated electric guitar part. In short, these two songs have much in common with the Sinatra and Zamfir tracks in terms of harmony, vocal treatment, arrangement, and instrumentation. To get the musical message, no one in the cinema needs to know that these songs come from Tarantino’s filmic models for Kill Bill, or that the lyrics tell of a woman’s journey of suffering and falling to the ground (‘Shura No Hana’ ) and the endless blues that men cause women (‘Urami-Bushi’). Through their association with each other and with the on-screen action, all these voices tell of a woman alone on a journey and beset by troubles.

Meiko Kaji, Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable, 1973

The movement in sequence between these pieces—from Sinatra to Kaji via Zamfir, and from America to Japan via panpipes—matches the Bride’s journey and the action’s location. At first, it’s possible that to a present-day American audience, the Kaji tracks, being Japanese, speak for the death of Oren Ishii. But surely that conception cannot last for long. Their appearance is a testament to Tarantino’s boldness in appropriating these Japanese film themes, and he has us effortlessly transfer their mood and emotion to the Bride’s sufferings and journey. The musical assortment within this film is also emblematic of Tarantino’s movement away from using artist record releases and toward the use of soundtrack albums. We can find a demonstration of his move away from artists’ releases at the opening of the final battle, where he gives us just two minutes of the rhythmic instrumental break from Santa Esmeralda’s 1977 Latin-disco version of ‘Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood’—the handclaps, drums, bongos, and acoustic guitar figures heard from 3 min./55 sec. to 5 min./55 sec. on the soundtrack CD’s 10-minute version—before, more importantly, Oren Ishii dies to the sound of old film songs, which are heard in full.

The soundtracks he has chosen from here, excluding the two Kaji ‘70s themes, are diverse. They vary from Japanese yakuza films through spaghetti westerns and Italian cop movies, to mainstream Hollywood thrillers and TV detective and superhero series. They deploy themes from composers and songwriters, including Bernard Herrmann, Ennio Morricone, Elmer Bernstein, Luis Bacalov, Al Hirt, Isaac Hayes, and Quincy Jones. But most of these are used in fragmentary form, only a few seconds of a strong musical figure or percussive rhythm (often electronic, blaring, or distorted, with strong bass), and are combined with RZA’s original loops, stings, and crashes to audio-animate or trigger the many fight sequences. The only thing that unites the appropriated soundtracks, apart from this characteristic violent deployment of extreme or percussive repeated figures, is that they are all drawn from the years 1967 to 1974.

Finally there are the more recent Japanese film score tracks that Tarantino selects for Kill Bill, most notably Tomoyasu Hotei’s funky re-recording of his theme from the 2000 film Another Battle/ Shin Jingi Naki Tatakai, ‘Battle without Honour and Humanity’; this is itself a tribute to an earlier series of Japanese yakuza films and features prominently at the appearance of Oren Ishii and in the Kill Bill trailers. Amid this audio diversity, and in contradiction to my argument about the Bride’s and Tarantino’s journey from songs to scores and from the US. to Japan, it is probably ‘Battle without Honour and Humanity’ that most people recall as the defining contemporary, funky, and violent ‘theme’ of Kill Bill, Vol. 1.

Then, in Kill Bill, Vol 2, we are surprised to find that Tarantino has wholly abandoned the Japanese yakuza, kung fu, and TV theme influences; he scores most of the action with film soundtrack themes, this time mostly from Morricone’s scores for II Mercenaria, A Fistful of Dollars, and Navajo Joe. These are interspersed with brief original guitar-based themes by Robert Rodriguez that aspire to these models’ spaghetti-western style and arrangements, without matching their intensity, originality, or memorability.

And then, suddenly, there’s a turn back; in the final chapter and end titles, these soundtracks and snippets are largely replaced by original artist records—music by Lole y Manuel, Malcolm Maclaren, Chingon (Rodriguez’s own band), and Shivaree—songs that aspire to create what might be a contemporary spaghetti western, or rather a Tex-Mex sound palette, as the action goes south of the border for the Bride’s showdown with Bill. Here the music increases in pace and percussive Latin effects, characterized across several tracks by handclaps, flamenco guitars, wailing female vocals, and, once again, tremolo and arpeggiated electric guitar figures.

Lole y Manuel

More than anything, it is this musical style that holds the frankly disappointing final chapter together, shifting the movie from past genres into an imagined dangerous and contemporary exoticism, a possible present tense. But it comes too late to save the soundtrack. Just as Tarantino used up all his best set-piece scenes in Vol. 1, so he seems to have run out of scoring ideas in Vol. 2. Little of the music chosen is especially memorable or has meaning recast by its narrative deployment, as is true of the Nancy Sinatra and Gheorghe Zamfir tracks in Vol. 1. Above all, the interaction between Morricone’s and Rodriguez’s themes is self-defeating; the latter fail to bring that characteristic sense of impetus, shock, and ‘musical moment’ that drives Tarantino’s better soundtracks. And perhaps it’s the need to maintain audio consistency with the new Rodriguez recordings that has discouraged any reflective display of vinyl or film-track glitches in the Morricone tracks after the main titles. The film finally gives the impression that it cannot decide if it wants to remind you what a spaghetti western sounded like, or if it wants instead to define an all-new Tex-Mex yakuza genre through audio means.

Robert Rodriguez, Chingon

Ken Garner on the Music of ‘Death Proof’

‘DEATH PROOF’: TWO-ACT MOVIE, TWO-ACT SCORE

From Ken Garner, ‘You’ve heard this one before: Quentin Tarantino’s scoring practices from Kill Bill to Inglourious Basterds’ in Arved Ashby, editor, Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV (OUP USA, 2013) pp. 170-171

In contrast to Kill Bill, the soundtrack to Death Proof does on its own limited terms have a basic formal symmetry mirroring the film’s two-act, crime-revenge structure. Setting aside the main titles, and the usual brief snippets of non-diegetic creepiness from Morricone and other scores as required, the first half is dominated by the R&B classic oldies that the girls choose from the jukebox in the Texas Chili Parlor.

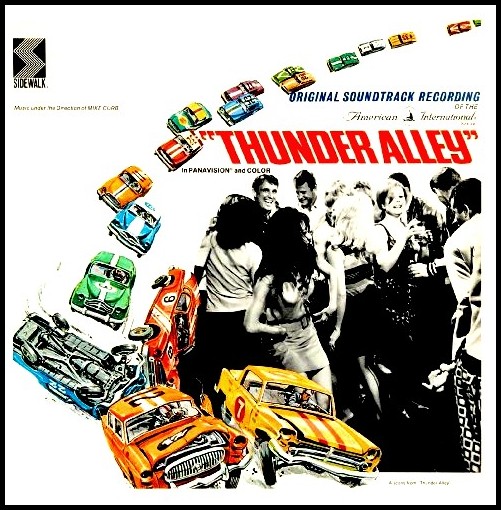

The second act, however, is scored mainly non-diegetically by hard-driving rock guitar and funk tunes and themes from Italian cop movie soundtracks of the ‘70s—sounds that really rev up in the ‘ship’s mast’ car chase conclusion. These uptempo driving tracks are clearly linked in style to Jack Nitzsche’s guitar instrumental main title theme—quite apart from its being repeated, once only, at the very moment when the female stunt actresses decide to ‘get the bastard’.

Thunder Alley

Nitzsche also produced the soundtrack album for Brian De Palma’s gay serial killer thriller Cruising (1980), featuring four tracks by Willy DeVille including ‘It’s So Easy’ The same cut features briefly in the Death Proof diegesis: Playing very forward in the mix and seemingly non-diegetically, the song is unexpectedly silenced when Stuntman Mike pulls up at the convenience store in Lebanon, Tennessee, alongside our new heroines, and turns off his in-car audio. Similarly, Lee is seen in the same scene singing along in the girls’ car to Smith’s version (presumably) of ‘Baby It’s You,’ the song previously heard on the Texas Chili Parlor jukebox and now playing on Lee’s iPod.

As in several Tarantino films, women seem to take over for themselves the emotion of the score. The women in Death Proof don’t do this the way the women in Pulp Fiction or Jackie Brown do, by having us see them choosing the records themselves; here, rather, in becoming the avenging instigators of the final chase in the second act, the women acquire the drive and excitement of the instrumental guitar rock tracks and Italian thriller themes as an agent or aid to their motivation, and we inevitably come to associate this power with them. Up to this point, these themes and loud guitars had been explicitly connected with the original pursuer, Stuntman Mike, and not just by the diegetic moment indicated above; in the main titles and under Nitzsche’s theme, we see several shots through his windshield of the roads and countryside where his second crime attempt will take place. In crude gender-positioning terms, we can say the film sets up a rather simple opposition, equating on the one hand R&B soul hits on the jukebox as providing the first-act girls with an alluring female sexual identity of consumption, but a kind of pleasure whose side effects they cannot control; and on the other hand, driving rock guitar soundtracks with the kind of machismo speed, pursuit, and violence that threaten death, but which our stunt-girl heroines in the second act are nevertheless able to master and claim as their own.

The end titles juxtapose April March’s kitsch-retro cover of Serge Gainsbourg’s ‘Chick Habit’—a song combining ‘60s girl group arrangements, driving reverb guitar, edited-to-the-beat triple blasts of trumpet choruses, and female backing vocals—with still images of both ‘60s girls and our heroines from the film in smiling out-takes. In doing so, the titles offer some recuperation in their amusing silliness and finger-wagging lecturing of predatory men. But Tarantino’s music, like his plot, leaves you wondering at an aesthetic that can casually assign gender-specific uses to entire music genres, even if one of those assignments gets flipped in the end. Given these simplistic aspects, Death Proof seems a long way from Jackie Brown and Tarantino’s nuanced use there of the Delfonics, Randy Crawford, and Bobby Womack.

April March

KEN GARNER: A BOOK, A CHAPTER, A TWITTER MUSIC FEED

KEN GARNER

Playlists

KEN GARNER – CHAPTER

Popular Music & The New Auteur

KEN GARNER

The Peel Sessions