William Forsythe

In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated

WILLIAM FORSYTHE: NIJINSKY’S HEIR

A CLASSICAL COMPANY LEADS MODERN DANCE

By Senta Driver

From Choreography and Dance, 2000, Vol. 5, Part 3, pp. 1-7

I first heard it from Paul Taylor: the suggestion that the real founder of modern dance was Vaslav Nijinsky. The notion comes, in fact, from Lincoln Kirstein. It rests on an appreciation of the choreographer Nijinsky’s profound innovations in movement design and group structure. Perhaps it also reflects that the Russian dancer was committed to a personal vision rather than to the primacy of the classical materials he inherited. What made us think Nijinsky was a ballet choreographer at all? The answer is probably his context, the Diaghilev company, and his training more than his actual product. Consider the choreographic material of his fully completed works. They could all be taken for radical modern dance, but they were performed by ballet dancers, and presented by a company with an otherwise classical repertory.

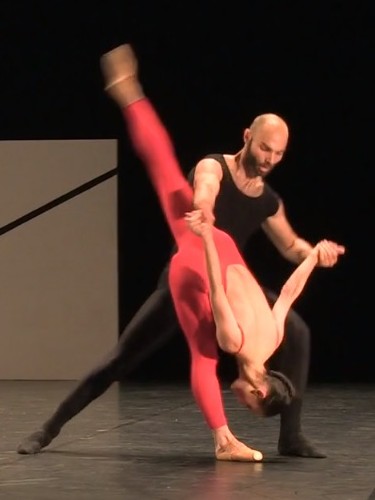

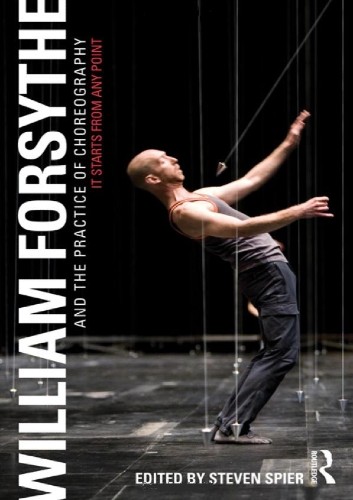

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Ballett Zürich | Photo: Gregory Batardon

The elements of the Russian ballet tradition were being used to forge an utterly original direction. What made us think George Balanchine ran what was essentially a modern dance company, compared to other ballet companies of his era? One usually cited his departure from the classic repertory and school of steps and his commitment to a single, progressive artistic vision and a distinctive movement vocabulary. Ballet is defined, like all arts, by its makers, and by the dancers and choreographers who accept influences that they find persuasive, and build upon them.

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Ballett Zürich | Photo: Gregory Batardon

When an artist with a thoroughly classical background is denounced on the grounds that he ‘destroys ballet’, either the work is weak or ballet has developed dangerously reactionary thinking. Those who do not make work are periodically moved to lock down its definitions: this was ineffective in 1912 when Nijinsky created his first full professional work, and it will continue to be so. We can celebrate a profound advance into new thinking when a choreographer spends his artistic life inside the classical school, shows veneration for the ballet d’école, informed respect for Balanchine and ballet history, and regular reliance on the pointe shoe, but makes work with unorthodox expansions of the vocabulary, fractured yet theatrically astute structure, and constant sympathies with the work of major modern dance innovators.

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Ballett Zürich | Photo: Gregory Batardon

William Forsythe has given his field a daring new direction and scope. His work is frequently begun in notions about light rather than music, as he reveals in Conversation on Lighting with Jennifer Tipton. Like the finest artists, he teaches the dance audience new skills for looking at things. For his sake we have developed a capacity to see in extremely low levels of light, even as his dancers have learned to be able to move freely, in groups, through a blackout. We can follow the logic of a known classical step through long new permutations. A penché may plunge in extraordinary directions, or a fouetté be created by picking up the dancer and hurling her manually around 360° as she executes the legwork — and we still recognize the source.

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Ballett Zürich | Photo: Gregory Batardon

As Forsythe has often stated, he treats the premises of classical technique as a usable language capable of new meaning, rather than as a collection of phrases and traditionally-linked steps that retain traditional rules, shapes, and content subject only to rearrangement. Aside from his enrichment of the ballet d’école, his approach greatly strengthens the dancers who use it. This is apparent physically as well as in their intellectual development, and it shows up in a look of knowledgeability and engagement on stage. Most dancers in outside companies who are cast in Forsythe pieces look like different artists in his work. They visibly know what a depth of information lies behind their movement.

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Ballett Zürich | Photo: Gregory Batardon

Forsythe has taught classical dancers to generate their own material by applying structural devices to their familiar technique. Drawing upon the theories of Rudolf Laban, which Forsythe has carried forward in what he calls Improvisation Technology, he vitally expands the movement vocabulary. His style has developed over the 14 years in Frankfurt from a forceful, weighted, and athletic one using the pointe shoe as a pole vaulter might, into a much warmer and more fluid realm. He has a permanent affection for pointework, and never abandons it for long, but recent works are sometimes danced in socks, soft slippers or even bare feet, and an increasing use of silence and tenderness is apparent.

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Photo: Herbert Migdoll, Joffrey Ballett

The dancers examine each other, touch and handle and interfere with each other in intricate assignments, and work extensively with and close to the floor. The structure of the pieces can seem confusing, but they are assembled with astute theatricality. They are carefully built to pace the evening well, and they progress with their own logic. His approach and movement thinking resonate with the methods of the great modern dance innovators such as Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown, and Twyla Tharp. Both his artists and the dancers of other companies who have worked with him demonstrate a range of new virtuosities. These days one rarely sees as much original material for the body in a whole season of modern dance as Forsythe offers at Ballett Frankfurt.

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Ballett Zürich | Photo: Gregory Batardon

The range of Forsythe’s thinking is illustrated by the various plans he made for a new work at the Roundhouse, a former trolley-car turntable shed in London. He has described three successive concepts: transformation of the building into a huge camera obscura with the image projected into the cellar onto a field of tightly packed narcissus; video on the skylight atop the building; and, finally, raising the ‘world’s largest bouncy castle’, an inflated structure with a trampoline floor in which the audience created all the movement. The piece, Tight Roaring Circle (1997), is known to him and Dana Caspersen, who made it with him, as the John Cage Memorial Choreographic Cube.

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | English National Ballet

Ballet tells us where ballet is going. Not even the most ardent devotees of what used to be can do that. We had half expected to see moderns, with their alleged superiority of imagination, take over the classical field. The stream of new choreographers making work on and off pointe for ballet companies suggested to some that the future of ballet lay outside its fold. Are we now looking at the opposite, a classically-based artist who emerges as a profound leader of modern dance? Certainly, in addition to his rich physicality, there is more adventure, more risk-taking in topic and visual design and structure in an evening at Ballett Frankfurt than one finds in most contemporary dance. There is also more aesthetic daring.

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Boston Ballet

Many modern dance artists have widened their reach into popular culture and its resources, but no one has managed a surreal parody of a Broadway musical, expertly sung Ethel Merman-style by an entire ballet company, quite on the level of Isabelle’s Dance (1986). Forsythe is, more simply, a profound leader of all dance, going in directions once reserved for moderns by means of a classical vehicle. He observed in the program of his April 1998 season at Theater Basel, ‘I use ballet, because I use ballet dancers, and I use the knowledge in their bodies. I think ballet is a very, very good idea that often gets pooh-poohed.’ He trusts the tradition. He believes it is his, and that it is fertile. What does his work say about the old dichotomy, now that he has opened ballet’s physical vocabulary, without losing its classical base, by the use of modern dance gambits?

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Boston Ballet

The illuminating factor in his process is his huge curiosity about everything around him, how it works and what happens if something is knocked awry. This and his simple, candid respect for other artists are the elements that stand out. Forsythe has profoundly enriched our art form in his 22 years of working, taking the utmost care to evade the center of attention. He has a remarkable capacity, such as I have only seen before in the great teacher Helen Alkire, for keeping his mind open and at work on new challenges. He has forged a new kind of beauty in dancing.

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | English National Ballet

WILLIAM FORSYTHE: ‘IN THE MIDDLE, SOMEWHAT ELEVATED’

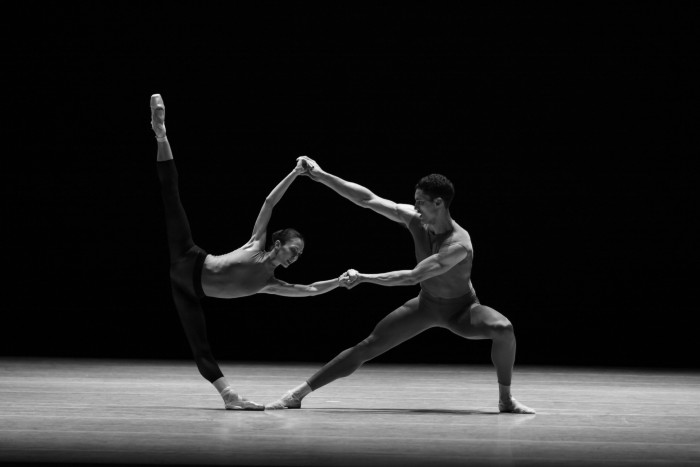

Pas de deux, ‘In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated’

Zakharova & Andre Merkuriev, Mariinsky Ballet

(Note: Poor quality video but outstanding performance)

‘IN THE MIDDLE, SOMEWHAT ELEVATED’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 10

With the applause my beating heart conspires to leave me breathless; I look into your eyes and see you are as stunned as I. What have we witnessed? Spiders in mating display? Matador and bull in the ceremonial kill? Karateka demonstrating combat stances? Aye, from our seats in the grand circle, we have seen the reinvention of ballet; we have seen the vestiges of academic virtuosity extended, accelerated and given a power that electrified the stage. Yes, in the Palais Garnier, two dancers in a pas de deux astounded us. Did they feel in their vertebrae, did they sense in their sinews, that this choreography is destined to endure?

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Photo: Herbert Migdoll, Joffrey Ballett

As the purity of their movements burned away all embellishments, did they know the erotic charge they were generating would lay bare our hearts? Unearthly angles and undulations, the steely majesty of wrenching turns: Who is the man with such a kinetic imagination? Helical motion and counter curvature, audacious extensions and volumetric form; off-kilter dynamics and casual contortions, high kicks and thrusting hips: Who is the master that conceived this miracle? Feline, vulpine, feminine, the sex and venom in a push-pull attack; virile, fluid, visceral, the violence and grace of a split kick snapped back: Who is the man who, in mingling the demonic and the divine, has resuscitated the corpse of classical dance? Forsythe. William Forsythe.

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | Ballett Zürich | Photo: Gregory Batardon

Was it his freedom that allowed him to turn the page on the past while preserving it in palimpsest? Was it his freedom that inspired the composer to write such unremittingly ecstatic music—telluric, architectonic, empyrean? Aye, was it his freedom that gave a spring to our step, a grace to our stride, as we stepped, hand-in-hand, into the night outside?

William Forsythe, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated | English National Ballet

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A novel by Richard Jonathan

‘IN THE MIDDLE, SOMEWHAT ELEVATED’: THOM WILLEMS, COMPOSER

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

THOM WILLEMS, MELODY OF THE METROPOLIS

Chantal Aubry, La Croix (French newspaper), 2 Nov 2000 | Translated by Richard Jonathan

Thom Willems, musical alter ego of choreographer William Forsythe, is as reserved in his daily life as he is assertive in his music. For the first fourteen years of his partnership with the director of the Frankfurt Ballet, no CD, no live recording, no concert outside of his work for the celebrated company has seen the light of day. Finally ceding to popular demand, he has recorded two of his most famous compositions, The Loss of Small Detail and In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated. The latter work inspired one of Forsythe’s most astounding pieces, premiered by the Paris Opera Ballet in 1987. It features both a metallic, aggressive sound, echoing a busy metropolis, and the hush of urban clamour filtered through closed windows. The din of the city, a metropolitan melody, an industrial soundscape that twentieth-century music draws on.

Thom Willems, The Loss of Small Detail & In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated

A Dutchman, born in Arnhem in 1955, Thom Willems began composing at the age of twelve, even before he was admitted to the Conservatory in The Hague. He belongs to no school, and refuses to be recruited into any. Indeed, he resists falling under any influence, especially that of the contemporary music the preceded him.

Thom Willems

His crucible: electronics. His principle: deconstruction, the principle of an entire generation, with architect Daniel Libeskind its beacon and William Forsythe its leading exponent in dance. ‘The sheer rock face of mountains in action movies, the steep gorges between skyscrapers; speed and vertiginous falls, rich tapestries of sound set off against ceaseless traffic’, as dance critic Eva-Elisabeth Fischer puts it, Thom Willems the musical craftsman also knows how to create an emotional subtext, a climate that’s a perfect complement to the one Forsythe’s dance generates. His music, you’ll have understood, transcends ‘ballet music’.

See also Michael Hoh’s interview with Thom Willems on the Staats-Ballett Berlin website.

Thom Willems

WILLIAM FORSYTHE: THREE BOOKS

Steven Spier, William Forsythe: Choreography

WILLIAM FORSYTHE: TWO DVDs

VIDEO: WILLIAM FORSYTHE INTERVIEW & 2 SHORT PERFORMANCES

All videos from NUMERIDANCE.TV Dance Platform. Click/tap the image to go to the video.