Art Pepper

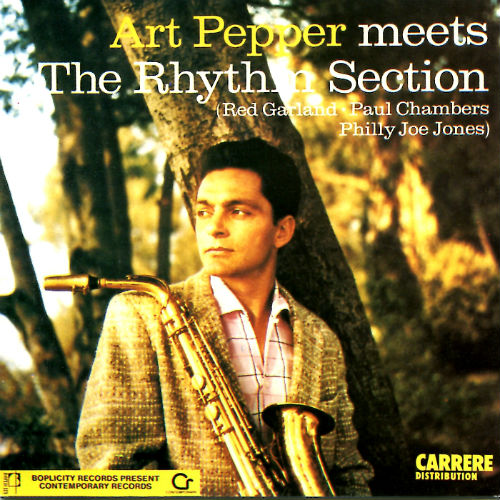

LESTER KOENIG ON ‘ART PEPPER MEETS THE RHYTHM SECTION’

The following text constitutes the liner notes to Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section (1957). See Spotify section below to listen to the album.

One of the great advantages of recordings is the special performance by jazzmen who ordinarily could not be heard together. And as one of the most absorbing aspects of jazz itself is individual expression, it can be fascinating to hear the impact of personality upon personality, and to capture permanently, by recording, the result of the impact. That happened Saturday afternoon, January 19, 1957, when altoist Art Pepper met pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Philly Joe Jones: The Rhythm Section.

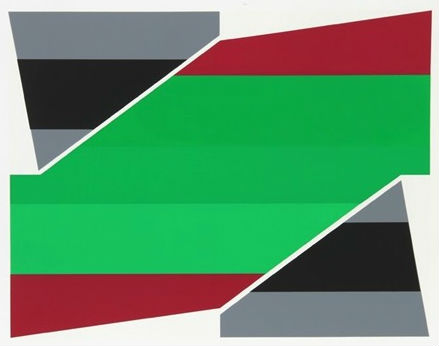

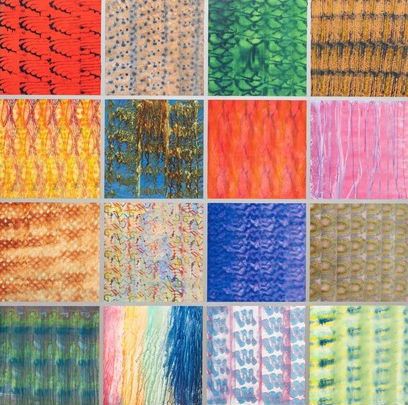

Larry Zox, Rotation series, 1980

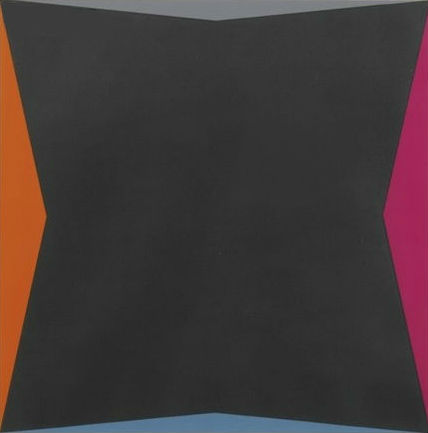

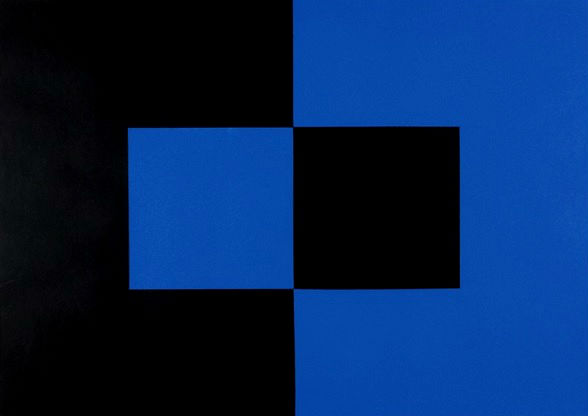

Larry Zox, Double Diamond, 1975

Pepper, one of the most exciting jazzmen of the 1950s, was known only in what might, for want of a better term, be called a ‘West Coast context.’ And The Rhythm Section, Easterners all, had been playing together for the past year and a half with the Miles Davis group. It seemed a provocative and challenging project to bring the two elements together. After the first chorus of the first rehearsal of ‘You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To’, there was no doubt in anyone’s mind the interaction was going to result in some unusually exciting jazz. Things happened fast after that, with everyone coming up with ideas, two new tunes (‘Waltz Me Blues’ and ‘Red Pepper Blues’) composed and worked out on the spot, and just five hours later this album had been recorded. It is a one-shot, unique jazz experience, giving the jazz fan and critic a ringside seat at a completely spontaneous and uninhibited blowing session.

Art pepper was born in Gardena, California, on 1 September 1925, moved to nearby Los Angeles when he was three, and moved again to the Los Angeles harbor at San Pedro when he was six. His father, who was a machinist when Art was born, became a longshoreman at San Pedro, and still lives and works there. From his earliest days, Art was interested in music. His mother’s family, the Bartolds, were all musicians, and his mother’s cousin Gabriel Bartold was a child prodigy on trumpet, appearing professionally. Art was very impressed by Gabriel, and anything that had to do with music. I used to stop in front of music stores and stare at the instruments. I didn’t want to leave. They’d have to drag me away, crying.

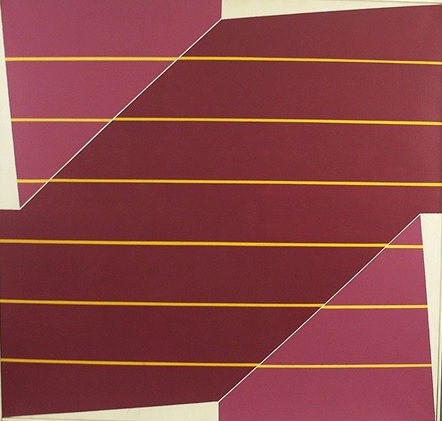

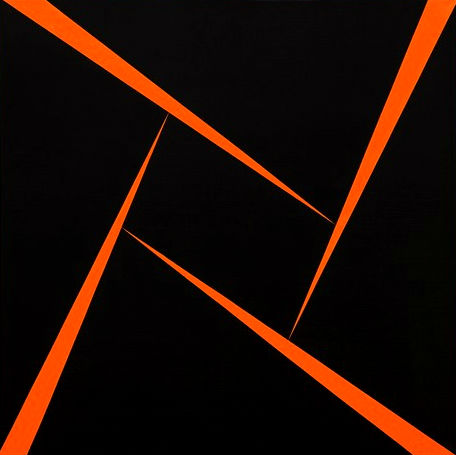

Larry Zox, Teepee Pillars, 1969

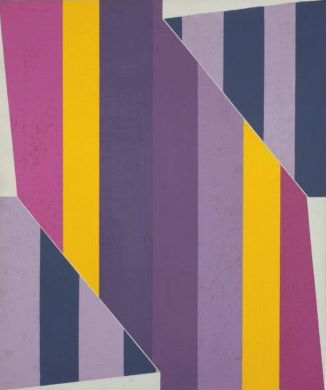

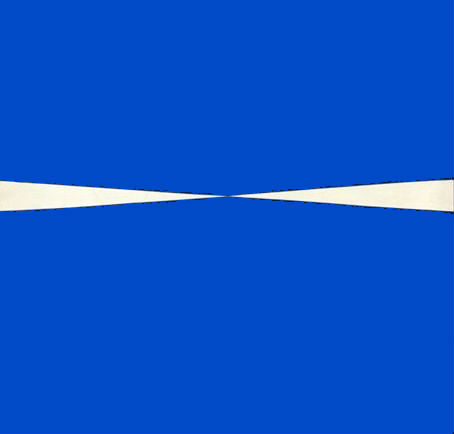

Larry Zox, Scissors Jack II, 1978

His father hoped Art would go to college and become an engineer, not a musician. However when Art was nine, he yielded to the boy’s passionate desire to study music, and sent him to a teacher, Leroy Parry. Art wanted to learn trumpet like his cousin Gabriel, but because several front teeth had been broken accidentally the year before, Parry suggested Art take up a reed instrument. Art was very unhappy about it, but began clarinet lessons, with the promise he’d be taught the alto saxophone as soon as he passed his clarinet test (‘The Flight of the Bumble Bee’). He did, and his father gave him an alto for Christmas the year he was twelve.

During this period he became very interested in jazz via records and radio. His idols were Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw. He also liked Jimmy Lunceford’s band, particularly the lead alto, Willie Smith. Another favorite was Muggsy Spanier. I had Muggsy’s records, Art recalls, and I used to practice by playing along with them: ‘Livery Stable Blues’, ‘Relaxin’ at the Touro’, and all the others. A lot of people think I’m putting them on when I say I like Dixieland. It’s all the same thing. Dixieland is just jazz in an earlier period. One happy result of this attitude is Art’s version of the Dixieland classic ‘Jazz Me Blues’ on this album.

Larry Zox, Scissors Jack, 1974

Larry Zox, Series I, 1970

When he was fourteen he played alto in his high school band and at local dances. By the time he was fifteen, he was committed to jazz, and started spending most of his time on Central Avenue, the main street of Los Angeles’ Negro community. From 1940 to 1943, instead of formal schooling, I used to stay out all night and blow. I attribute whatever ability I have to play jazz to those times on the Avenue. I didn’t know what a chord was, but I was in an atmosphere of great jazz feeling, and I think it stayed with me ever since.

He played in after-hours spots like The Ritz Club at Central and Vernon, and the upstairs club known as the Brothers. Among his musical companions were Dexter Gordon, Charlie Mingus, Gerald Wiggins, Zoot Sims and Joe Mondragon, all now well-known in modern jazz. Late in 1942 he joined Gus Arnheim for his first big band job, but left after two months because ‘it was too commercial’, returning to the jazz of the after-hours spots. Dexter Gordon got him set with Lee Young’s band at the Club Alabam, and for part of 1943 he played with Young until 2 a.m. moving over to The Ritz to play a second job until 7.

Larry Zox, Broken Series III, 1970

Larry Zox, Twin Polygons, n.d.

Later in 1943, Lee Young recommended Art to Benny Carter, and Art worked with the Carter band in Hollywood and Salt Lake City. After that the Carter band was heading into the South and on Benny’s suggestion, his manager brought Art to audition for the Kenton band. He was hired, and spent the next seven or eight months with Kenton. While with Kenton he had his first record date (19 November 1943) and first recorded solo on ‘Harlem Folk Dance’. The bridge was difficult, and Art found out how much he didn’t know when he saw a B-flat chord on the music. Up to that time he’d played everything by ear. Now he realized he would have to learn the fundamentals of music. I was a little afraid that I might lose some of the jazz feeling if I studied, but I was wrong. If you’ve got the jazz feeling to begin with, knowledge of music and technique on your instrument will be a great help.

In February 1944, when he was eighteen and a half, his musical career was interrupted by the draft. He spent the next two and a half years in uniform: basic training for six months, and then a band, just before it went overseas. After several months in England, the band returned to the United States, and Art was transferred to the military police, as acting sergeant of the guard in charge of the Marlborough Street Jail in London. You should have seen me. I was on 24 and off 24 and carried a sawed off shotgun. While stationed in London, Art played some jazz concerts at the Adelphi Theater, and met many of the top British jazzmen including George Shearing and Victor Feldman, then a child prodigy on drums. He also played a concert with Ted Heath’s band.

Larry Zox, Rotation series, 1964

Larry Zox, Rotation series, 1964

He left England in 1946, returned home to be discharged in June. In September, when the Kenton band was reorganized in Balboa, Art rejoined for a five year stay. During the years with Kenton, and the five years on his own, Art developed into one of the outstanding alto stars with an international reputation. His services have been in great demand; he has played and recorded with most of the best jazzmen on the West Coast. Since 1956 he has led his own group in Los Angeles.

Although the rhythm section is composed of three individualists, each of whom has established a reputation on his own, the year and a half together behind Miles Davis has fused them into a unit. Philly Joe Jones, born of course in Philadelphia, in 1923, is rapidly becoming recognized as one of the great jazz drummers. ‘Tough’ is the word they use for him. He generates tremendous excitement, swings like mad, and can play delicate patterns with brushes on the snare or cymbals when a soft and delicate sound is appropriate. Paul Chambers, one of the rising young bass stars of the East, is also a hard swinger, as well as a gifted soloist, and is noted particularly for his bowed solos. He was born in Pittsburgh in 1935, first came to prominence in Detroit in the early ‘50s, and has been with Miles Davis since 1955. Red Garland was born in Dallas in 1923, and has been an active pianist with many leading groups since 1945.

Larry Zox, Rotation series, 1970

Larry Zox, Diagonal, 1963

The session itself started off in the worst possible way. Art didn’t know about it until the morning of the date. Arrangements were made by Art’s wife, Diane, who didn’t want him to become tense worrying about it. He hadn’t been playing for a couple of weeks. His horn was dried out, the cork in the neck was broken, and he had no idea of what he’d record. To top it all, everyone had been up late the night before and were late in getting started. But after the first rehearsal of ‘You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To’, everything jelled. As Art says, I was so inspired by the rhythm section, I forgot the ‘adverse’ conditions. I’d never played most of the tunes before, and I fell back on the time I spent before the war on the Avenue playing by ear. Otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to make it.

About his own playing, Art says: In some spots I may sound rough, like I’m squawking, but I finally realized that in playing I’ve got to play exactly as I feel it. I want the emotion to come out rather than try to make everything perfect. You can’t express your emotions that way. I believe I’m coming closer to that kind of honest emotion in this album. It’s hard to drop all the inhibitions built up over the years, but I’m gradually beginning to free myself.

Larry Zox, Diagonal IV, 1963

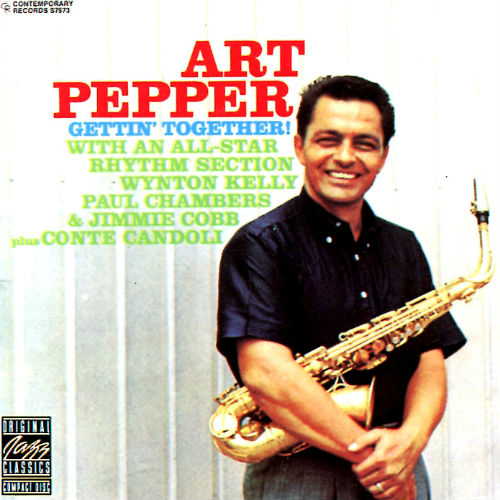

MARTIN WILLIAMS ON ART PEPPER: GETTIN’ TOGETHER

The following text constitutes the liner notes to Gettin’ Together (1960). See Spotify section below to listen to a playlist featuring all the tunes on the album except ‘Bijou the Poodle’ (not available).

Luiz Zerbini, Janelo do Mundo, 2019

The square’s question about jazz may not be such a bad question if you think about it. I mean the one that goes, ‘Where’s the melody?’ or ‘Why don’t they play the melody?’ We could borrow the famous mountain climber George Mallory’s answer: ‘Because it’s there’. But a more helpful one might be, the melody is whatever they are playing, or to put it more directly, they don’t play it because they can make up better ones. And if I wanted to introduce the square to that fact, one of the first people whose work I would use to show it would be Art Pepper.

This album is a sort of sequel to the earlier Art Pepper Meets The Rhythm Section, a set I would call one of the best in the Contemporary catalogue. That one was made in 1957 and the rhythm section of the title was the very special one of the Miles Davis quintet of the time: Red Garland, piano; Paul Chambers, bass; Philly Joe Jones, drums. This one is made with the (again special) Miles Davis rhythm section of February 1960. Paul Chambers is still there, Wynton Kelly is on piano, Jimmie Cobb is on drums. That former session was made under pressure, for not only was the section available only briefly, Pepper himself had not played for two weeks before the night it was done. For this one, the Davis group was again in town only briefly, and again, there was only one recording session. In fact, the last track, ‘Gettin’ Together’, made because Art wanted to record a blues on tenor, is just Pepper, Kelly, and the rest playing ad lib while the tape was kept rolling. All of which does not mean that either session was made with the kind of haste that makes waste.

Carmen Herrera, Nocturne, 2016

Luiz Zerbini, Vazio, 2018

I began by saying that I would use Art Pepper’s playing to convince our square friend that jazzmen can make up better melodies than the ones they start with. (Others I would use for similar reasons might be Jack Teagarden, Lester Young, Duke Jordan, Miles Davis and Benny Morton.) And I could well begin with an Art Pepper recording like ‘Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise’, for Pepper states that theme with none of its usual melodramatics and proceeds to make up melodic lines spontaneously that are superior to those he began with. And I might also use it as an example of the emotional range he can develop within a solo from a very limited point of departure, and without eccentricity or crowding.

Pepper is a lyrical and melodic player. Very good test pieces for such qualities are slow ballads—and many a jazzman of Pepper’s generation wanders aimlessly and apologetically through such tests. There are two ballads here. ‘Why Are We Afraid?’ is a piece Art Pepper plays in the movie The Subterraneans. ‘Diane’ is named for Art Pepper’s wife. It is an emotionally sustained piece of improvised impressionism, and Kelly also captures and elaborates its mood both in his accompaniment and solo. Unlike many comparable players of his generation in jazz, Art is not so preoccupied with making a melody that is ‘pretty’ that he falls into lushness or weakness in his melodic line. What saves him is a kind of rhythmic fibre and strength that some lyric and ‘cool’ players decidedly lack. (‘Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise’ is again a very good example). For that reason, it should surprise no one to hear him, particularly on the tracks where he plays tenor here, absorbing some rhythmic ideas from the better players in the current Eastern ‘hard’ school. And to show how well they fit and are assimilated, that ad lib blues, ‘Gettin’ Together’, is prime evidence. Surely one of the things that makes jazz so unsentimental and fluent an art is the jazzman’s rhythmic flexibility, and that is something Art Pepper has always been on to.

Carmen Herrera, La mañana, 2006

Luiz Zerbini, Diagonal prata, 2015

The events of Art Pepper’s biography include the fact that he took his first music lessons at nine, but had been passionately interested in music even before that. In his teens he was fully committed to jazz and playing nightly on Central Avenue in Los Angeles with Dexter Gordon, Charlie Mingus, Gerald Wiggins, Zoot Sims, and at eighteen he was a regular member of Lester Young’s brother Lee’s group. Subsequently he was with Benny Carter and achieved his widest recognition when he joined Stan Kenton on alto for the second time, from 1946 through 1951. When these tracks were made he was, with Conte Candoli, one of Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse All Stars at Hermosa Beach. If ‘Bijou the Poodle’ (Pepper’s dog, by the way) and Thelonious Monk’s ‘Rhythm-a-Ning’ have a somewhat more prepared air to them than the other tracks, it is because Pepper and Candoli (whose past includes trumpet chairs with Woody Herman and Kenton) were playing them regularly at Rumsey’s club.

As I said, Chambers (who is surely as innately a jazz musician as any man ever was; indeed, a handy explanation of ‘swing’ might be ‘any two successive notes played by Paul Chambers’) has been with the Miles Davis groups since 1955. Wynton Kelly’s past is illustrious enough to have included work with the other major trumpeter in the modern idiom, Dizzy Gillespie; he has also accompanied Dinah Washington and Lester Young, among others. Jimmie Cobb was brought into the Davis group at the suggestion of Cannonball Adderley in 1959.

Carmen Herrera, Untitled, 2014

Luiz Zerbinin, Venus, 2018

It should come as no surprise that Art finds playing with a rhythm section picked by Miles Davis such a pleasure and stimulation. It is true that those two hornmen ‘use the time’ (as musicians put it) differently; Pepper is closer to the beat in his phrasing for one thing. But Miles Davis is a unique combination of surface lyricism, concentrated emotion, and a decided, but not always obvious, rhythmic flexibility. (He has been called a man walking on eggshells; a man with his kind of inner emotional terseness would surely crush eggshells to powder.) The rhythm sections he picks for himself might therefore be ideal for Art Pepper because, although I don’t think they convey emotion in the same way, they have many qualities in common. Miles’ rhythm sections have been accused of playing ‘too loud’ by some people. I am not sure what that means exactly, but I am sure that they are never heavy and always swing at any dynamic level they happen to be using, and that is a very rare quality. Their swing always has the secret kind of forward movement that is so important to jazz.

There are several other things on this record that gave me pleasure that I would recommend you listen for. One of the first is the unity of Pepper’s solo on ‘Whims of Chambers’ and the way it builds. (You cannot make a good solo just by stringing phrases together to fit the chord changes—but nobody admits how many players don’t try to do much more than that.) The unity is subtle, but it is not obscure, and once grasped it becomes a delightful part of experiencing the solo. For instance, if you keep the phrase he opens with in mind, then notice how much of the solo is melodically related to that phrase. And also how much of it is related to Chambers’ theme. Such unity is never monotonous because Art Pepper gets inside of these melodic ideas, finds their meaning, and develops them musically—he is never just playing their notes or playing notes mechanically related to their notes.

Carmen Herrera, Untitled, 1956

Luiz Zerbini, Tatú Bola, 2018

The curve of the solo is also a delight. In a very logical way, more complex lines of shorter notes begin in Art’s third chorus (that is the one where Kelly re-enters behind him). They reach a peak of dexterity in the fourth, tapering to a more lyric simplicity at its end. There is a very effective echo of those more complex melodies at the end of the fifth chorus, as the solo is gradually returning to the simpler lines it began with. (There is nothing really difficult or forbidding about following these things; if you can follow a ‘tune’ you can follow these melodic structures, although they are far more subtle and artful than a ‘tune’ is. And following them gives the kind of pleasure that digging deeper always does.)

Thelonious Monk’s ‘Rhythm-a-Ning’ may sound like only a visit to that ‘other’ jazz standard (other than the blues, that is) which its title indicates. It isn’t just that. And the best part is the ‘middle’ or ‘bridge’. Most popular songs are written with two melodies and if we give each a letter to identify it, the form of them comes out to be AABA. That B part of ‘Rhythm-a-Ning’ is an integral part of the piece because its melody is a development of one of the ideas in the A part. The other thing is the way it is harmonized. You can easily hear that it is unusual when they play it the first time. Hearing what they do with it in the solos I leave to you to enjoy. I was also intrigued with the idea that Monk would get a smile out of Pepper’s writing on ‘Bijou’.

Carmen Herrera, West, 1965

Luiz Zerbini, Logo-love, 2018

A musician friend who had recently returned from California and was answering my questions about Art Pepper said, ‘I think maybe Art knows now that he plays not to win polls or be famous or any of that, but just because he has it in him to play and he just needs to’. If a man has come to that insight, I think you can hear it in the way he plays. I think I hear it here.

ART PEPPER INTERVIEW: THE EVOLUTION OF AN INDIVIDUALIST

Posted by kind permission of Les Tomkins.

From a series of interviews with Art Pepper conducted by Les Tomkins in 1979. Originally transcribed from the pages of Crescendo magazine by Ron Simmonds and posted on his Jazz Professional website, they were subsequently posted on the National Jazz Archive, a site where you will find the complete series of interviews. © 1979 Les Tomkins.

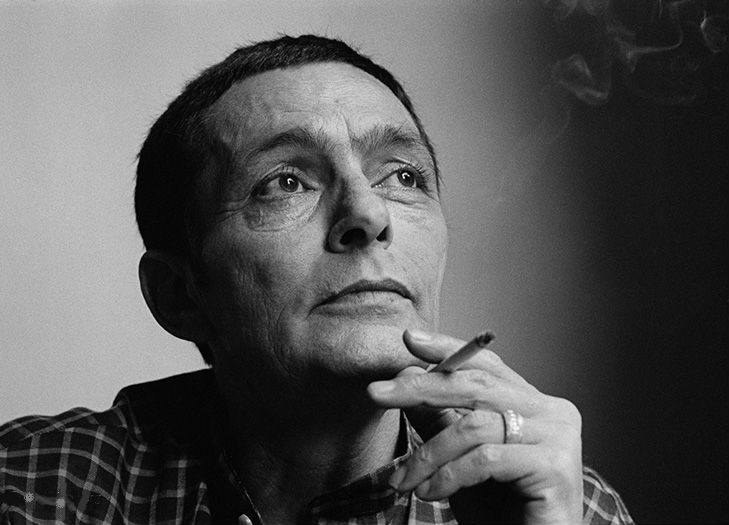

Art Pepper | Photo: Andy Freeberg

If you have individuality in music, it’s something to hold on to. In Lester Young’s playing there was the beauty of music. It was melodic, swinging, a beautiful sound—everything was there. Then when he got older, with so many people telling him he should play like Ben Webster or Coleman Hawkins, all of a sudden he started playing louder and with a vibrato—and just destroyed himself. It was such a shame, just awful.

But it’s very hard to be an individual. When I joined Kenton the second time, after the Army, everybody listened to Charlie Parker records or classical records, or Woody Herman. They’re all saying: ‘Oh, that’s the greatest player in the world. Nobody can play like him’. And it was really a drag at that point, to be thought of as nothing in comparison to Charlie Parker. ‘He’s the only person that’s saying anything’. I disagreed with that—but it didn’t change the way they felt. So it was hard to keep playing yourself, because people really try to change you. Fortunately, I was able to hold my own. Until I heard John Coltrane, and then I fell by the wayside for a little while. But fortunately again, I’m back to myself again. I didn’t feel it was a hang-up to be in the Coltrane bag; other people thought it was. They changed. When it was Charlie Parker, then it would be okay to play like Parker, but Coltrane, it wouldn’t be okay to play like him. I don’t know why. They must have had some reason.

Art Pepper, Stan Kenton Orchestra, 1950 | Photo: Bob Willoughby

But I thought it just helped my growth as a musician, going through the Coltrane thing. If I had stayed playing like him, then it would have been bad. It was just like when you go to school and take a certain course for a year or a couple of years. Your technique, your facility, becomes that much greater. It helps your approach, you can do so many more things and incorporate them into the way you feel about music, your own feelings about your style. In the long run, it gave me a different dimension, and it just broadened the whole thing.

The way so many musicians slavishly imitated Coltrane—that’s the way it was with Charlie Parker. Only even more so, if that can be imagined. Everyone that I knew changed totally. But they took the worst things of his playing; that harsh sound, it just didn’t come off the way they did it. The way he did it was great; their way wasn’t good at all. I just would listen to them and say, ‘That’s a Bird imitator’. And that would be it. I would never care to listen to them again.

Alto is just a very hard instrument; there are so few people that play it really well. I feel it’s the best one, too, now. At first I didn’t feel that way—I wanted to be a tenor player. It took a long time for me to feel that alto was the most expressive of the saxophones.

As for that whole West Coast era, it was a great opening to reach the people, even though it made me angry to be pigeonholed like that. Some good records came out of that period, like Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section, with the Miles Davis rhythm section of the time—Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones. Gettin’ Together, on similar lines, was even better.

The next period in my life, because of my addiction problem, was a terrible one. But I don’t think I could have avoided it. I mean, I tried to stay out of it for a long time, knowing what it might do. I think that in my searching for something—for love, acceptance, or whatever it is—to be a real man, to relate to my father—all those things—going to prison was a help. It was part of my evolution, as a human being and as a musician. I feel that I have much deeper feelings now than I would have had, had I just been a musician all that time, which would have been a very dull existence. You know, I wanted something more than just being thought of as a musician, period. To be labelled ‘Art Pepper, musician’, period, would just be awful, what a boring life that would be. At least I was able to go in a lot of different directions, seeing how things were from another viewpoint. I got to know myself better, definitely. I was seeing what I was capable of, what my feelings were, what my morals were. All those things are very important. What kind of strength I had, the fact of dealing with certain situations, and with a whole different type of people. People were very honest, I found, in that other thing—much more so than musicians. Now, I play music, but I’m not a musician. I don’t know if I’m getting across what I’m trying to say… Yes, what I have become as a person is what matters most.

ART PEPPER IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 13

‘You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To’: Easy and elegant, Art Pepper blows his pinched and jittery tone through the changes of Cole Porter’s urbanity. The alto sax brings a brooding quality to the bouncy melody, telling us insouciance is not all it’s cut out to be. I think of Straight Life, Art’s brutally honest autobiography; I think of the abortion his mother wanted him to be: Something in his tone remembers—his lyricism is all the more moving for being naked and raw.

Art Pepper | Photo: Ray Avery

SPOTIFY: THREE ART PEPPER ALBUMS

Art Pepper, Gettin’ Together (1960)

Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section (1957)

Art Pepper Quintet, “Smack Up” (1960)

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

ART PEPPER: TWO BOOKS & A FRENCH RADIO DOCUMENTARY

Click on the France Culture image to go to the page, then click ‘play’.

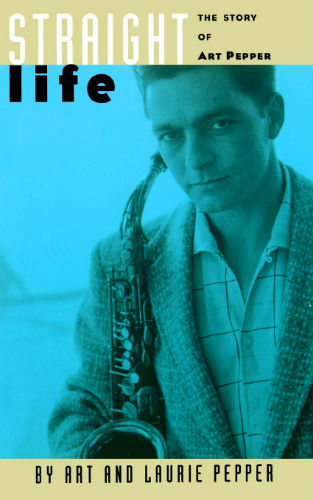

Art & Laurie Pepper, Straight Life

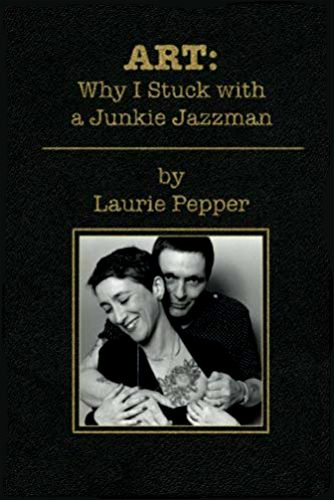

Laurie Pepper, Art : Why I Stuck…