You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

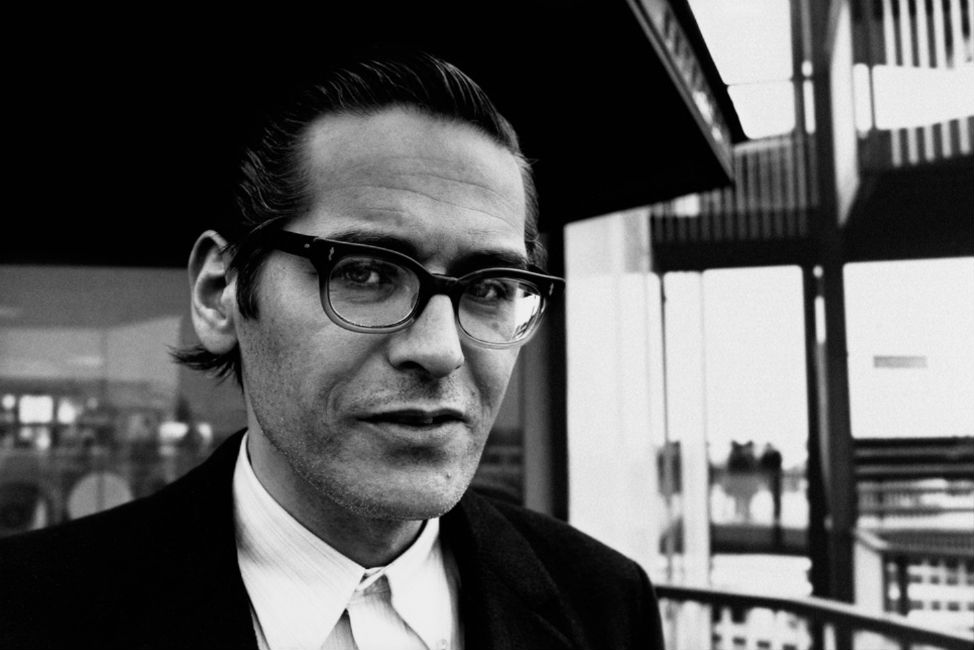

Bill Evans

Bill Evans | Roberto Polillo, 1969

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 10

̶ Hey, Bill Evans!

Florence snaps her fingers to the beat and gives the name of the piece:

̶̶ ‘You and the Night and the Music’.

Onyx and jade circle her wrist in brilliant cubes of black and green: the power of Cleopatra. As the piano’s melodic line transports us to the buffet, the bent of Flo’s mind makes me wonder: Will she go home with Xavier tonight? If so, when they make love, how deep will she take him into her godless universe? And will he be man enough to find the divine in it?

MARTIN WILLIAMS: HONORING BILL EVANS

From Martin Williams, Jazz Heritage (Oxford University Press, 1985), pp. 59-69

Several times Bill Evans spoke publicly of a singular moment when he first discovered the freedom that goes with being a jazz player. And several times also he spoke of the enormous requisite discipline that went with it. About the freedom, he was playing as a pre-teenager with a dance band in his home state of New Jersey. The group was doing ‘Tuxedo Junction’, a piece which was originally produced and performed in an atmosphere of improvisation in the Erskine Hawkins band, and in most of the other big swing bands that later adopted it. But by the time ‘Tuxedo Junction’ had become a dance-band ‘stock’ arrangement, the parts had been simplified, locked in, and ready to be read off the paper. ‘For some reason,’ Evans said, ‘I got inspired to put in a little blues thing. ‘Tuxedo Junction’ is in B-flat, and I put in a little D-flat, D, F thing—bing!—in the right band. It was such a thrill. It sounded right and good, and it wasn’t written, and I had done it. The idea of doing something in music that somebody hadn’t thought of opened a whole new world to me.’ On the question of the discipline that is a part of the equipment of any great improviser, Evans spoke often. Even on the most uninspired occasion, on the most, uninspiring job, he once explained, he could approach the bandstand with no hope of having anything good in him to play, and the accumulated discipline of knowing how to make his mind and hands and feet respond when the inspiration did come, that discipline itself would simply take over and let—even cause—the flow of musical ideas to be there.

Bill Evans | Roberto Polillo, 1965

Orrin Keepnews, Scott LaFaro, Bill Evans, Paul Motian | Steve Schapiro, 1961

When the Bill Evans Trio was formed in 1959, the leader said that he hoped it would ‘grow in the direction of simultaneous improvisation rather than just one guy blowing followed by another guy blowing. If the bass player, for example, hears an idea that he wants to answer, why should he just keep playing a 4/4 background? The men I’ll work with have learned how to do the regular kind of playing, and so I think we now have the license to change it. After all, in a classical composition, you don’t hear a part remain stagnant until it becomes a solo. There are transitional development passages—a voice begins to be heard more and more and finally breaks into prominence. Especially, I want my work (and the trio’s if possible) to sing. I want to play what I like to hear. I’m not going to be strange or new just to be strange or new. If what I do grows that way naturally, that’ll be okay. But it must have that wonderful feeling of singing.’ It is perhaps up to commentators like me to point out that the Trio’s bassist, Scott LaFaro, was then moving jazz bass along the lines that it had been going for some time—with Charlie Mingus outlining the way—and that he was doing it with an irresistible virtuosity. The mono version of ‘Autumn Leaves’ from the Trio’s first studio date and the original take of ‘Blue in Green’ are the initial masterpieces in just the kind of three-way performances Evans had hoped for.

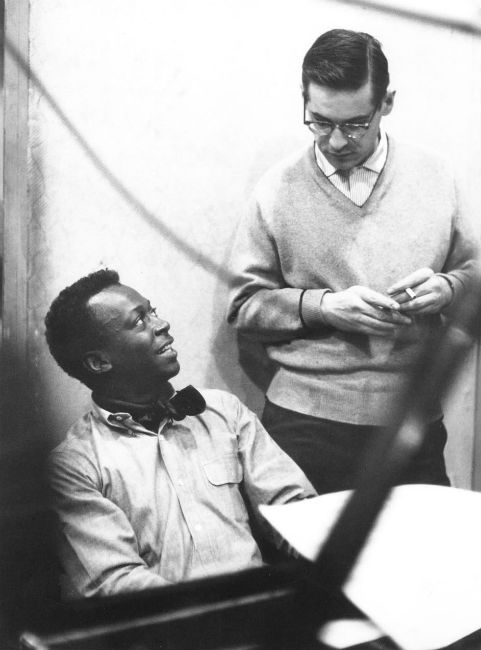

Bill Evans could have been a major musician-critic. Take the notes he contributed to the seminal Miles Davis Kind of Blue LP (1959). Evans compared ‘the extremely severe and unique disciplines of the jazz or improvising musician’ to the art of the spontaneous watercolorists of Japan, who paint on a thin parchment ‘in such a way that an unnatural or interrupted stroke will destroy the line or break through the parchment. Erasures or changes are impossible. These artists must practice a particular discipline; that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.’ The pictures that result, he added, may ‘lack the complex composition and textures of ordinary painting, but it is said that those who will see will find something captured that escapes explanation.’ Or take the comments Evans wrote for one of Thelonious Monk’s Columbia LPs. He called Monk ‘an exceptionally uncorrupted creative talent,’ who was largely uninfluenced by any musical tradition except that of American popular music and jazz. Monk had, against huge conformist pressures, replaced formal superficialities with ‘fundamental structure’ and produced ‘a unique and astoundingly pure music which combined aptitude, insight, drive, compassion, fantasy and whatever else makes a total artist.’ Or these words on Miles Davis’s development (from an interview in 1981): ‘He is an example of somebody I think was a late arriver, even though he was recorded when he first came on the scene. You can hear how consciously he was soloing and how his knowledge was a very aware thing. He just constantly kept working and contributing to his own craft. And then at one point it all came together and he emerged with maturity, and he became a total artist and influence, making a kind of beauty that has never been heard before or since.’

Miles Davis and Bill Evans | Don Hunstein, 1958

Miles Davis and Bill Evans | Don Hunstein, 1958

But like any important artist-critic, Evans was, in no self-serving way, also speaking of himself, his own struggles and growth, whenever he discussed others. His remarks on Monk’s commitment to the jazz and popular traditions, for instance, were a comment on Evans. ‘I believe in the language of the popular idiom,’ he said later, ‘and this has come out of not just our culture but all of history, especially the traditional jazz idiom. It is the experience of millions of people and of conditions which are impossible to take into consideration. Now if I could take the feelings and experience I have from this traditional idiom and somehow extend it to another area of expression… I want everything to have roots.’ His comments on Miles Davis were a part also of one of the most succinct of his many comments on the need for discipline and (most important) his insistence on the need for the artist to arrive at his own best style, the one that would allow for a continued artistic growth and development. Indeed, this seems to me one of the most perceptive statements in all the literature of jazz: ‘I always like people who have developed long and hard, especially through introspection and a lot of dedication. I think what they arrive at is usually deeper and more beautiful than the person who seems to have that ability and fluidity from the beginning. I say this because it’s a good message to give to young talents who feel as I used to. You hear musicians playing with great fluidity and complete conception early on, and you don’t have that ability. I didn’t. I had to know what I was doing. And yes, ultimately it turned out that these people weren’t able to carry their thing very far. I found myself being more attracted to artists who have developed through the years and become better and deeper musicians.’

That need to know what he was doing—intellectually, theoretically—was one pull of the dichotomy of this remarkable combination of careful deliberateness and intuitive spontaneity, of logic and sensitivity, mind and heart, that was Bill Evans the musician. He elaborated—in a singular account of a musical self-education—to Don DeMichael in the introduction to the music folio Bill Evans Plays. ‘I think it was a good thing I didn’t have a great aptitude for mimicry, though it made it very difficult for me at the time because I had to build my whole musical style. I’d abstract musical principles from the people I dug, and I’d take their feeling or technique to apply to things the way that I’d built them. But because I had to build them meticulously, I think worked out better in the end because it gave me a complete understanding of everything I was doing… I don’t want to express just my feelings, my feelings aren’t interesting to everybody.’

Miles Davis and Bill Evans | Don Hunstein, 1958

John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Miles Davis, Bill Evans | Don Hunstein, 1958

In view of Evans’s commitment to the American popular song as his major vehicle—a subject we shall return to—his recording called ‘Peace Piece’, his superb ‘free’ solo on George Russell’s ‘All About Rosie’, and his participation in the Davis LP Kind of Blue call for special comment. These events either lead to, or were early parts of, the movement variously called ‘modal’ jazz or ‘free’ jazz. And they were efforts on the part of jazz musicians to find new bases for improvising, after they had explored basically the same bases for over thirty-five years. Of ‘Peace Piece’, Evans said at the time, ‘It’s completely free form. I just had one figure that gave the piece a tonal reference and a rhythmic reference. Thereafter, everything could happen over that one solid thing. Except for the bass figure, it was a complete improvisation. We did it in two takes. Because it was totally improvised, I haven’t yet been able to do it again when I’ve been asked for it in clubs.’ ‘Peace Piece’, like ‘Flamenco Sketches’ on the Kind of Blue album, is conceived as a succession of scales which the soloist takes up one at a time, improvises on for as long as he pleases, and then turns to the next, The notes available to the improviser are a ‘given,’ but the structure, phrase length, and the overall length are spontaneous.

‘Blue in Green’ was also on Kind of Blue. It was written by Evans on a succession of unusually juxtaposed chords apparently suggested to him by Miles Davis, and on a ten-measure, rather than twelve-measure, phrase. Strictly speaking, ‘Blue in Green’ is neither ‘free’ nor ‘modal,’ but it is very challenging to the player, requiring him to get gracefully as well as correctly from one chord to the next and ‘think’ in phrases of unusual length. And just for the record, the other highly influential piece on Kind of Blue, ‘So What’, is opposite to ‘Flamenco Sketches’, but is like the flowing ‘Milestones’. Phrased like an AABA popular song, the piece gives the player 16 measures of one scale (or mode), eight of another, then back to eight of the first. In other words, he’s got the notes to choose from and his phrase lengths assigned, but no assigned chords to wend his way through. However, it was Evans’s left hand chord voicings that had the widest effect on other musicians, and they are not too difficult to explain to the layman. Bill voiced certain chords, that is, he chose the notes to go in those chords, leaving out the ‘root’ notes. The roots tie down the chord and its sound. Without them, a given chord can sometimes have several identities; it can lead easily, consonantly, to a wider choice of other chords, and it can accommodate a wider choice of melody notes and phrases for the player on top of the chords. The ‘open’ voicings that Bill used opened up melody and flow in new ways for jazz. It’s as simple, and as important, as that.

Bill Evans | Roberto Polillo, 1965

If all of this seems too technical to the reader, let him go to Evans’s version of ‘Young and Foolish’. The piece is in C. Within a half-chorus, Bill is in D flat. And he ends in E. Gracefully, easily, eloquently. The proof of the theory is in the new and unexpected beauties it allows the artist to bring us. And often, and most effectively, without our even noticing. When Bill Evans first came to jazz piano, Bud Powell was the dominant influence on most younger players, and Powell, whose best recorded work had largely been done by the mid-1950s, was a frustrating influence. Easy to imitate in some aspects by players who knew less about the keyboard than he did, Powell seemed impossible to emulate, and too many of his followers had settled into a kind of middle-register glibness, in which horn-like treble phrases were bounced off of self-accompanying bass lines of ‘comping’ chords. Only Horace Silver had evolved a personal style under Powell’s spell, a virtually irresistible one, by reintroducing large doses of blues (i.e., minor thirds) with an assertive swing (‘he sounds like Bud imitating Pete Johnson’ said one wag at the time). We heard a lot of very good Powell and some good Silver on Evans’s first record. Try ‘Our Delight’ for Powell, or ‘Displacement’ for Silver, or ‘No Cover, No Minimum’ for both. And we also heard something of the enigmatic, peripheral style of Lennie Tristano. What was not so evident was Evans’s professed admiration of Nat Cole as a jazz pianist, evidence of that later became clearer with a change in touch and with Evans’s evident commitment to ballads.

I suppose if Bill Evans had done nothing else, he brought some of Tristano’s ideas into the mainstream of jazz. But he did much else. To do it, he had to sacrifice some things. The swing that he gave us on ‘All About Rosie’, and which can be heard virtually throughout his first LP, was a conventional swing, and Evans, to be Evans, had to find his own kind of rhythmic momentum, a momentum integrated with his evolving personal touch and use of dynamics, and his own sense of musical phrase and melodic flow. I should not leave that first session without pointing out ‘Five’, Evans’s ‘I Got Rhythm’-based piece whose theme laid out his characteristic interest in rhythmic displacement, with ‘turning the beat around’ on a single short phrase. (If those words don’t make the challenge clear, play the opening chorus of ‘Five’ and it will be.) The twenty-six months that passed between Bill Evans’s first and second Riverside LPs were patently fruitful, and what can be heard on the second LP is a remarkable, emerging Bill Evans style, his influences assimilated (or abandoned), his own approach fully integrated, if not fully developed. And what one hears subsequently is the style’s development, and the development of an ensemble style for the Evans Trio. The Powell-like bluntness a touch was gone; the Silver-like bluesiness no longer evident (perhaps because the style came to seem all too easy to be truly expressive for anyone except Horace himself). The Evans touch—gentle, delicate, always integrated with perceptive pedal work—had begun to emerge. He seemed, as Miles Davis said, to make a sound rather than strike a chord, but try to decide which notes in any Evans chord were struck forcefully and sustained, and which softly, to achieve those sounds!

Bill Evans | Tom Copi, 1969

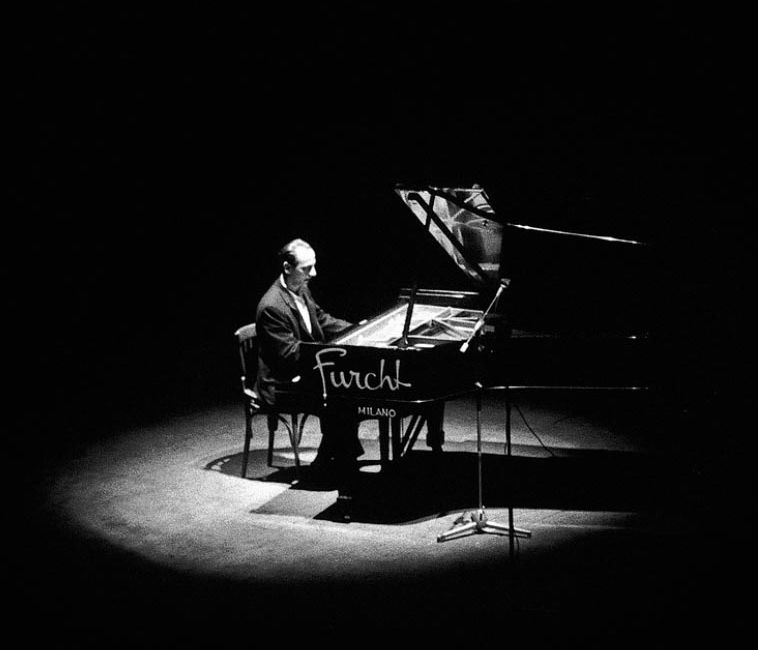

Lennie Tristano | Roberto Polillo, 1965

Most telling is the musical flow: the flow of ideas one to the next, the magic flow of sound between the hands—the integration of the hands. He was now a pianist discovering the instrument and its resources as he needed them, not a stylist imposing ideas on a keyboard. Returning to the Tristano effect, I find one of the first signs of its assimilation was the way Bill slides into the melody of Harold Arlen’s ‘Come Rain or Come Shine’, teasingly, obliquely, gradually. It was an occasional device which Bill made his own: theme-statements that seem to evolve from improvisation rather than the usual other-way-around. That, and the parallel motion of the two hands on a single phrase. Bill once spoke admiringly of ‘the way Tristano and Lee Konitz started thinking structurally,’ and the words suggest that Tristano’s horn-playing ‘students,’ Konitz and Warne Marsh, affected him as much as did the pianist himself.

Time changes things. It would be foolish to deny that. Even our best and most thoughtful reactions, even our deepest and least transient selves, grow and therefore change. To Evans and the Trio themselves, the ‘live’ Village Vanguard sessions reportedly did not seem so remarkable while they were doing them as they did later in the studio editing sessions, and as they did later still on the LPs. And they no longer seem so uncommunicative to me as they did in 1961. Perhaps I did not properly respond to the rapport among the three men. Still, the Vanguard sessions seem no less introspective to me, yet Evans seems—paradoxically perhaps—no less uncompromisingly exposed emotionally. I think Bill Evans was the most important and influential white jazz musician after Bix Beiderbecke—and that statement is no reflection on the contribution or the importance of Bunny Berigan, Benny Goodman, Jack Teagarden, Dave Tough, Stan Getz—does Django Reinhardt belong on such a list?—or any other. Partly my statement seems valid to me because of Evans’s intrinsic merit, and partly because his effect on the music has been so general—technically, in ways I have commented on, emotionally in its uncompromising lyricism. At the same time I. think that in the future, his work may come to seem somewhat isolated from the mainstream—as Bix’s now does—but no less valuable and no less authentic and no less beautiful.

Bill Evans | Ray Ross, 1968

Bill Evans | Tom Copi, 1980

Bill Evans’s major contribution was, as I say, in an abiding lyricism—again like Beiderbecke’s. But such a remark is an observation and a description. It is also perhaps a limitation., But would one complain that Lester Young was always playful? Coleman Hawkins dramatic? Or, for that matter, Beethoven humorless? No, it would be as foolish to deny that lyricism pervades all aspects of Evans’s work as to deny the element of privacy in some of it. I can say more about that later quality as I hear it on the previously unissued solo performances that have appeared since Evans’s death. They seem to me some of the most private and emotionally naked music I have ever heard. I was shocked at them on first hearing, and if Bill Evans were still with us, I’m not sure I would want to hear them. But I have said that times changes even our least ephemeral selves. So does death. And ‘All the Things You Are’, ‘Easy To Love’, ‘I Loves You Porgy’ (a fine sketch for the Montreux masterpiece version on Verve), and the rest now seem to me a heritage invaluable and without precedent in recorded jazz. There were times when I heard Bill Evans and thought that if you take this music—so exposed, so unprotected emotionally, so completely naked in its feeling—into the real world, that world would crush it and crush the man who made it. Perhaps after all that is what happened.

Len Lyons, The Great Jazz Pianists

Alain Gerber, Bill Evans (in French)

Martin Williams, Jazz Heritage