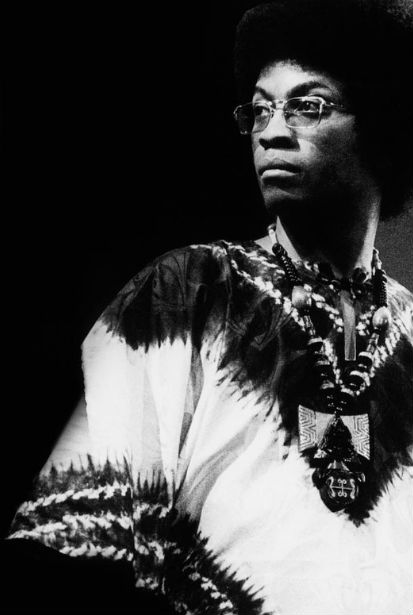

Herbie Hancock

NAT HENTOFF ON HERBIE HANCOCK: ‘SPEAK LIKE A CHILD’

The following text constitutes the liner notes by Nat Hentoff to the Herbie Hancock album, Speak Like a Child (1968). See Spotify section below to listen to the album.

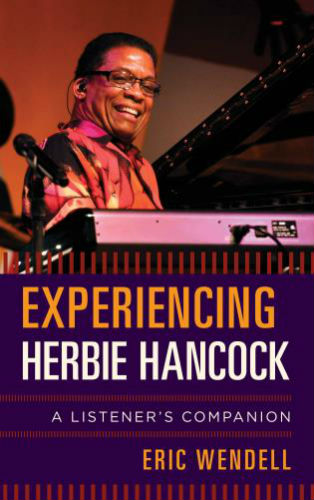

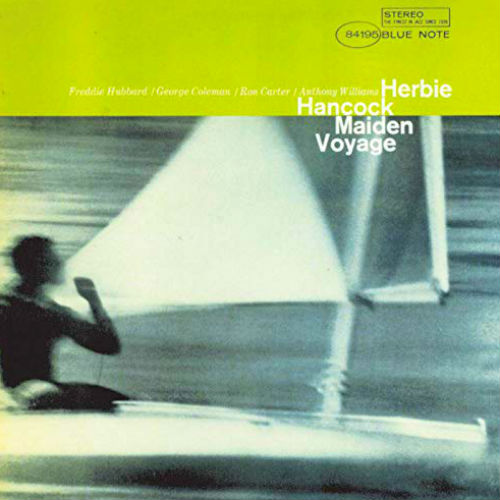

Speak Like a Child (1968) is Herbie Hancock’s first album as a leader for Blue Note since Maiden Voyage (1965) and it represents a further extension of discoveries Herbie made during that preceding journey. It is related to Maiden Voyage, Herbie notes, ‘in a way none of my previous albums were related to each other. That set was a sort of jumping off point for me, and I go on from there here.’ I asked him for specifics. ‘What I was into then, and have been thinking about more and more’, Herbie answered, ‘was the concept that there is a type of music in between jazz and rock. It has elements of both but retains and builds on its own identity. Its jazz elements include improvisation and it’s like rock in that it emphasizes particular kinds of rhythmic patterns to work off of.’

Paul Klee, Föhn in Marc’s Garden, 1915

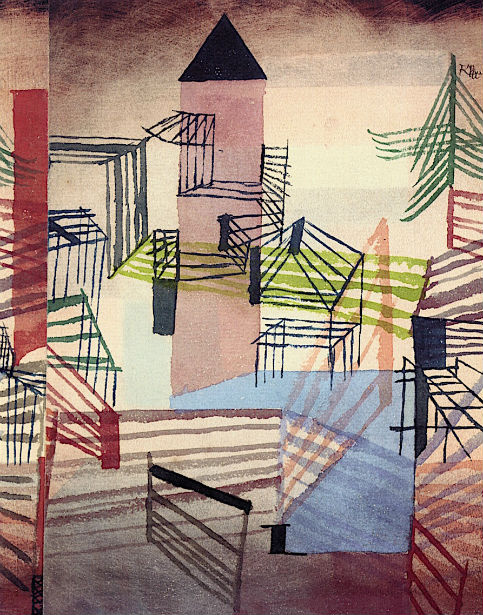

Paul Klee, Fortress, 1921

‘This album,’ he continued, ‘also is an extension of Maiden Voyage in terms of my use of simple, singable melodies. Now what’s different in Speak Like a Child as a whole has to do, first of all, with harmony. For the most part, the harmonies in these numbers are freer in the sense that they’re not so easily identifiable chordally in the conventional way. I’m more concerned with sounds than chords, and so I voice the harmonies to provide a wider spectrum of colors that can be contained within the traditional chord progressions. In much of the album, there are places where you could call the harmonies by any one of four designations, but no one designation would really include everything involved. That’s how I write; that’s how it comes out.’ ‘Similarly,’ Herbie went on, ‘on those tracks with the horns, I was more interested in sounds than in definite chordal patterns. I tried to give the horns notes that would give color and body to the sounds I heard as I wrote. Some of this way of thinking and writing comes from listening to Gil Evans and Oliver Nelson and from having worked with Thad Jones from time to time. Certainly one of the ways I’m going to go from here on is writing for large groups.’

The first number, ‘Riot’, was recorded originally by Miles Davis. ‘When I listened to the record,’ Herbie said, ‘it sounded like a riot to me with regard to the emotions being expressed. This version, however, is less riotous. It does contain an element of turmoil, but it’s there more as an undercurrent than on the surface. Incidentally, when I wrote this song, I wrote the melody first and then added the harmonies I wanted underneath. I suppose I heard them vaguely in my head from the beginning; I just had to find them.’

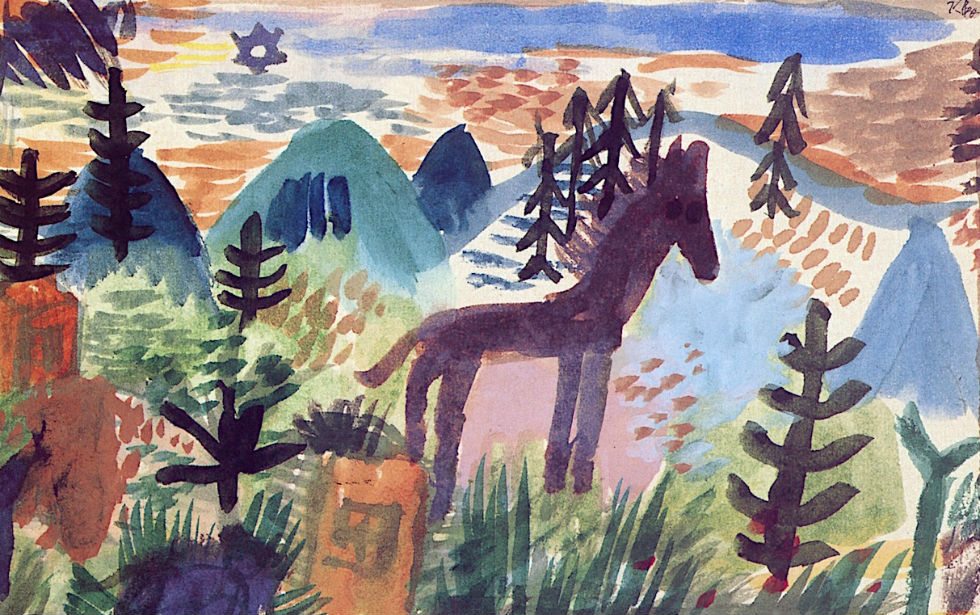

Paul Klee, The Horse, 1918

Paul Klee, Pathetic Watercolor (Red), 1915

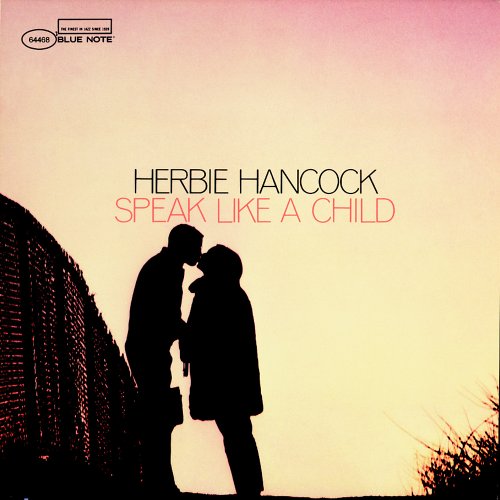

Speak Like a Child, as a title, Herbie explains, ‘came from Frank Wolff, and it’s a result of a picture that a friend of mine, David Bythewood, took. I dug it so much I brought it to Frank for use as the cover for this album. Frank said it was so evocative a photograph because of the innocence and naivete in it. And so I started thinking about the quality of innocence while writing this song. Clearly the music doesn’t sound too much like what’s going on today—war, riots, the stock market getting busted up. And the reason it doesn’t, I realized, is that I’m optimistic. I believe in hope and peace and love. It’s not that I’m blind to what’s going on, but I feel this music is a forward look into what could be a bright future. The philosophy represented in this number, and to a large extent in the album as a whole, is child-like. But not childish. By that I mean there are certain elements of childhood we lose and wish we could have back—purity, spontaneity. When they do return to us, we’re at our best. So what I’m telling the world is: ‘Speak like a child. Think and feel in terms of hope and the possibilities of making ourselves less impure.’ Herbie also points out that ‘Speak Like a Child’ is a sectional piece and has no definite tonal centers. It should also be noted that the attractive young lady on the cover is Herbie’s fiancée, Gigi Meixner.

‘First Trip’ is by Ron Carter and both the title and the tune itself strike Herbie as having a sense of childhood. ‘When I played the melody,’ Herbie adds ‘I didn’t play it straight. I made some small changes, played a little with the time, and staggered some of the phrases. As for the time, I played some phrases in five, some in seven. It’s the kind of thing I’ve become used to working with Tony Williams and Ron Carter so now that kind of approach to time just comes out naturally as I play.’ Herbie also spoke about the rhythmic feeling of the album as a whole. ‘I’ve been trying for a long time to work on swinging, to feel more and more comfortable in terms of swinging. And of all the albums I’ve done, this to me swings the most.’

Paul Klee, Garden in Dark Colors, 1923

Paul Klee, Plant in Late Autumn, 1934-35

As for the harmonies of ‘First Trip’, ‘this tune too has the kind of progressions that go in and out of the traditional dividing lines,’ Herbie emphasized. ‘The emotions here and in other pieces require freer harmonic developments and as a result, we get away from finite structural and chordal limitations.’ Ron Carter wrote the song originally for his little boy, Ron Jr. At the time, his son was going to a nursery school where the kids who behaved well in class came home on the first trip. The ones who acted up had to wait for the second trip. ‘My son,’ Ron remembers, ‘was elated that day, and the song is about how he felt and is also a little tribute from me to him for one of the times he did indeed behave very well.’

‘Toys’, Herbie observes, ‘originally came about because I was thinking of writing a blues without it being a blues—a tune with the colors of the blues but not the form. Like ‘Blues for Pablo’. Some of the techniques in the writing of it I think I’ve gotten from Gil Evans. There are times, for instance, when I sacrifice the vertical for the horizontal structure in going from one chord to another a few bars later, and the reason is to allow certain instruments to play a melodic line even though that line may involve some harmonic clashes. But I make sure those clashes have their own kind of validity and body. There are also, as in ‘Riot’ and some of the other pieces, carefully conceived contrasts in dynamics.’

Paul Klee, Pineapple Pear, 1933

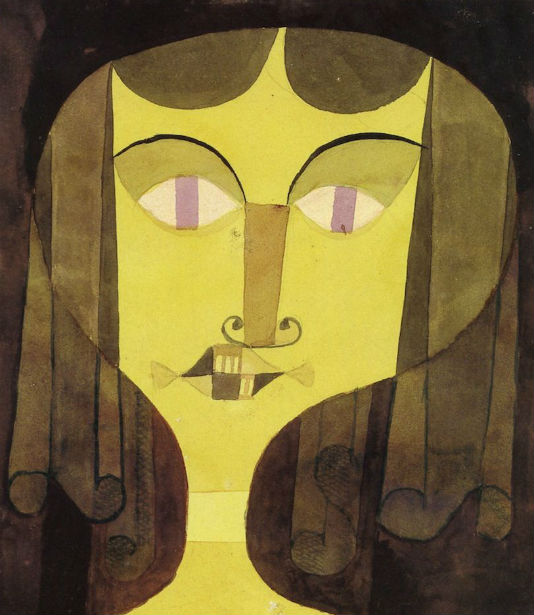

Paul Klee, Violet-Eyed Woman, 1921

‘Goodbye to Childhood’ reflects, Herbie says, ‘that particular quality of sadness you feel at childhood being gone. In the writing of it, I again didn’t think about what the chords were. I had to figure out what they were afterwards.’ ‘The Sorcerer’, originally written for Miles Davis, receives its title, Herbie smiles, ‘because Miles is a sorcerer. His whole attitude, the way he is, is kind of mysterious. I know him well but there’s still a kind of musical mystique about him. His music sounds like witchcraft. There are times I don’t know where his music comes from. It doesn’t sound like he’s doing it. It sounds like it’s coming from somewhere else.’

Speaking of the album as a whole, Herbie concluded: ‘All the sounds in these pieces are a product of everything I’ve learned, particularly in recent work with Gil Evans and, of course, in the five years I’ve been with Miles and the other men in the band. I feel I have to go on and write more for horns, explore more possibilities of textures. There are things I hear in my head that I don’t often hear in other people’s music, and I want to get more of those down. And I keep hearing new things and I have to find out what value they have, how they work out.’ It sounds clear to me that Speak Like a Child is an impressive further stage in the evolution of Herbie Hancock as writer and player. From the first time I heard him, I felt Herbie had a singular quality of incisive, searching lyricism. And as his experience has deepened and become more diversified, his music has become both more personal and more challenging. In Speak Like a Child, Herbie Hancock has created a durably pleasurable montage of those elements of childhood which remain in people who continue to be responsive, spontaneous, open to hope and to that sense of wonder that is essential to being fully alive.

Paul Klee, Pretender, 1939

HENRY MARTIN & KEVIN WATERS ON HERBIE HANCOCK AND ‘HEADHUNTERS’

From Henry Martin and Kevin Waters, Essential Jazz: The First 100 Years, 3rd edition (Boston: Schirmer, 2014) p. 204

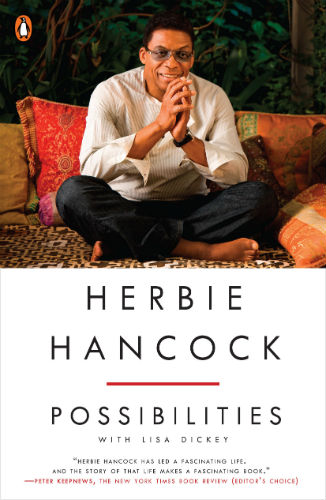

After leaving Miles Davis’ band, Herbie Hancock continued his exploration of electronic media on his recordings Mwandishi (1971), Crossings (1972) and Sextant (1973). Hancock’s group for these recordings—usually sextet—was booked into rock music venues such as the Filmore, but their spacey, open-ended improvisations proved unsuccessful and Hancock was forced to disband the group in 1973.

Before abandoning the rock circuit, however, Hancock had the significant experience of opening for the R&B pop group the Pointer Sisters at the Troubadour club in Los Angeles. Hancock was impressed by the direct audience appeal of the Pointer Sisters. He started thinking about taking his music in a direction that had more popular appeal, one rooted in the funk and R&B styles of James Brown, Stevie Wonder, and especially Sly and the Family Stone. Introduced to Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism by his bassist, Buster Williams, Hancock experienced a revelation while chanting: My mind wondered to an old desire I had to be on one of Sly Stone’s records. It was actually a secret desire of mine for years—I wanted to know how he got that funky sound. Then a completely new thought entered my mind: Why not Sly Stone on one of my records? My immediate response was: ‘Oh no, I can’t do that’. So I asked myself why not. The answer came to me: pure jazz snobbism.

Although Hancock never recorded with Stone, he did achieve a breakthrough into popular culture with his phenomenally successful album Headhunters (1973). The album reached number 13 on the Billboard chart and then eventually went platinum (sold a million copies). His intent, Hancock claimed, was to hire not jazz musicians who could play funk but funk musicians who could play jazz. Headhunters extensively used overdubs and studio technology. Hancock played not only the Fender Rhodes electric piano but also other electronic keyboards. Hancock’s solo on ‘Chameleon’ established him as one of the finest live performers on synthesizer. Much of the success of Headhunters was due in fact to ‘Chameleon’, which became a hit largely because of its syncopated, danceable two-measure bass riff and catchy melody. Although Hancock was later criticized for ‘selling out’, not all of the compositions on Headhunters were overtly commercial. For example, ‘Sly’, an homage to Sly Stone, included several drastic tempo changes.

HERBIE HANCOCK IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 10

Layered washes and pools of light articulate the huge volume of the room, two floors tall under its glass roof, bringing an excitement to the space that the hubbub of the guests intensifies. From the railings edging the galleries, serpentine streamers in bright metallic colours, interspersed with silvered balloons, fall to varying depths. Floating above the ferment, Herbie Hancock’s piano, textured with the tones of flugelhorn and flute, weaves a dreamy web. I feel your presence beside me, I feel your head held high, as we walk into the room.

Herbie Hancock

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 15

̶ Ten minutes. That’s the time you’ve got to get to know each other before I move you on.

So says Adelaide as she leads us across the room. Funky bass line, earthy feeling; sax, synth and drums: Threading its animality through our spinal marrow, Herbie Hancock’s ‘Chameleon’ gives our stride an offbeat energy.

SPOTIFY: THREE HERBIE HANCOCK ALBUMS

Herbie Hancock, Speak Like a Child

Herbie Hancock, Headhunters

Herbie Hancock, Maiden Voyage

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

VIDEO: HERBIE HANCOCK – TWO LIVE PERFORMANCES & ONE MUSIC VIDEO

Herbie Hancock, Speak Like A Child, 1984

Herbie Hancock, Chameleon, 1975

Herbie Hancock, Rockit, 1983

JOHN FORDHAM ON JAZZ FUSION

From John Fordham, Jazz: History, Instruments, Musicians, Recordings (London: Dorling Kindersley, 1993) pp. 44-45

The extremes of jazz in the 50s and early 60s were the cool school with its tricky time-signatures and melodic intrigue, and the beginnings of a new, hot free music that seemed at first to have no rules at all. But if both approaches appeared closer to art music than show business, the historical connection between jazz and dance had not withered away in the 50s. It just did not make the papers.

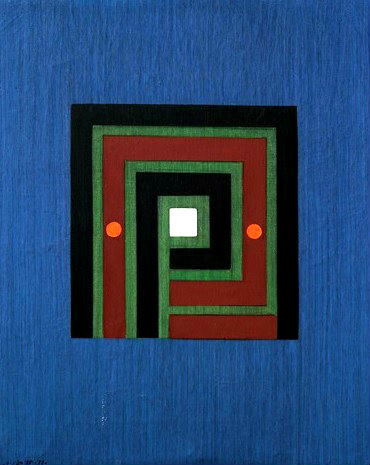

Ho Kan, Abstract 2017-030, 2017

Ho Kan, Abstract 2017-044, 2017

Nor had the prophets of the New Thing arrived from another galaxy. Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane had learned their craft in blues bands, playing dance-halls and bars. Ray Charles’s clamorous, gospelly big bands of the 50s showed how tight the relationship of blues and hard bop was, as did pianist Horace Silver. The modern descendants of the boogie-woogie pianists arrived, Hammond organists like Jimmy Smith and Jimmy McGriff, halfway between jazz and rhythm and blues, and saxophonist Eddie ‘Cleanhead’ Vinson was still as bluesy as a guitar player.

Funky jazz was not just an American phenomenon. Late-50s Britain spawned skilled blues musicians from the skiffle ‘jugband’ boom, who frequently drew on jazz for inspiration. John McLaughlin made his breakthrough in the driving rhythm and blues band led by the late Graham Bond, and 60s British R&B stars like Cream’s Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker cut their teeth on the London jazz scene. Even cool jazz had flirtatious fusions with dance, though they took an appropriately languid form. The graceful saxophonist close to the cool school, Stan Getz, collaborated with a group of Brazilian musicians to spark off the seductive bossa nova craze. Fusion existed long before it became a genre and gained a capital letter.

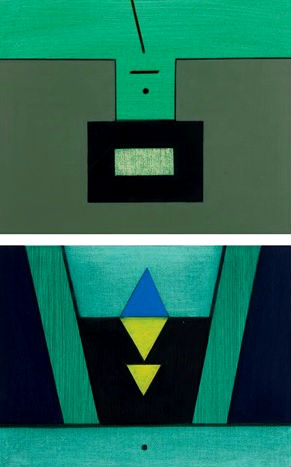

Ho Kan, Untitled, n.d.

Ho Kan, Untitled, 1999

By 1965 a mass-movement of young rock fans heard jazz as the bearer of a dated message. Their parents had jazz record collections. It was time for something new—in music, fashion, personal politics, and ethics. A more complex, extended, instrumental and improvisational rock music (often using modal methods) was uniting tens of thousands of entranced listeners. Massive outdoor festivals seemed to sustain the dream of a community of youth with its own values and language and without frontiers that could inhabit a world of its own. In the States, disaffection with an older generation’s legacy intensified with racial tension and the war in Vietnam.

Box office and record sales declined for jazz. Even Miles Davis started to notice the difference–and if he did, every other jazz musician would have been noticing it more. It was not just expediency that moved jazz musicians toward the new rock, even if Columbia’s executives began dropping hints to Davis that he might broaden his listening habits. Not every young musician wanted to be a rock and roll star. Many still loved jazz and learned its craft, but the sound palette was now far more colourful. The Moog synthesizer was used by jazz improvisers from the mid-60s. Ray Charles had played an electric piano in 1959, and its glittering sound appealed to jazz keyboardists like Herbie Hancock. Guitarists would no longer simply dream of cloning the soft, deft, rounded sound of Wes Montgomery or Jim Hall, but could now mix it with the howl of Jimi Hendrix. Upright bass players learned to double on bass guitar.

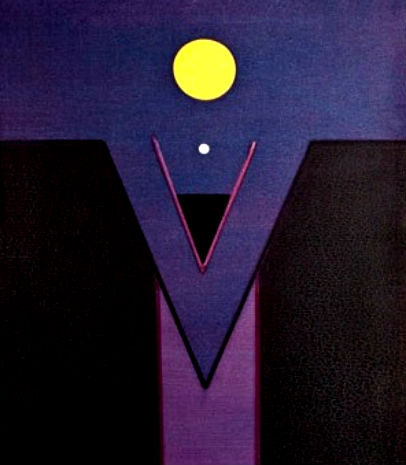

Ho Kan, Untitled, 1976

Ho Kan, Untitled, n.d.

Jazz-rock, or fusion—mingling bop, R&B and fatback funk devices lifted from Motown, Stax, James Brown and from bands like Sly Stone’s—grew by the day. The word ‘jazz’ was frequently dropped from marketing as bad for business. Bigger bluesy bands like Blood, Sweat and Tears and Chicago featured horn line-ups with jazzy licks. Vibes player Gary Burton pioneered the remarkable technique of bending notes like a blues guitarist, and began to play a mix of jazz and country-blues in the later 60s, introducing creative young guitarists Larry Coryell, Pat Metheny and John Scofield. Another vibist, Roy Ayers, fused catchy song-writing with Afrocentric funk. Saxophonist Yusef Lateef, a broad-minded artist who had long drawn on music from other cultures, imaginatively explored jazz funk, as did trumpeter Randy Brecker and his virtuoso saxophonist brother Mike. Professor Donald Byrd at the University of Southern California, formerly a Blue Note trumpet star, collaborated with students like Mizell brother producers Larry and Fonce, taking jazzy street funk to the discos with the best-selling Black Byrd and now highly collectable Places and Spaces. He forged a market for younger musicians like pianist Patrice Rushen and his students the Blackbyrds, who took the sound onto 45 format with singles such as ‘Do It Fluid’.

But, not for the first time, the convert who became the most charismatic preacher of a new gospel to jazz musicians in this period was Miles Davis. The band the trumpeter had been leading with Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Tony Williams and Ron Carter had stretched jazz improvisation to the limits of freedom compatible with maintaining a structure and a pulse. Now Davis steeped himself in the music of Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix. With all his old audacity, he spliced the solo resources of a sensational band into an electric music that still had space, drama and surprise but increasingly used electronic effects to paint active backdrops as haunting and suggestive as Gil Evans had produced with a conventional orchestra. In a Silent Way and Filles de Kilimanjaro began a change for Miles Davis that passed through a big-selling classic of fusion atmospherics. Bitches Brew was followed by less distinct phases bordering on disco—electronics made his unique trumpet sound more impersonally guitar-like—and on to the hip hop and rap sounds of the 80s and 90s.

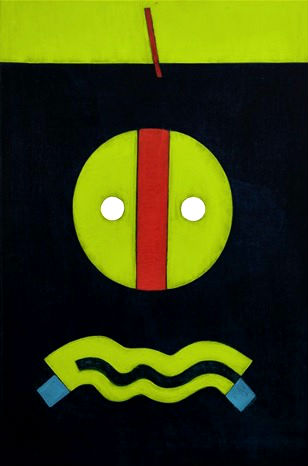

Ho Kan, Untitled, 2008

Ho Kan, Untitled, n.d.

Davis’s sidemen branched into fusion experiments of their own. Wayne Shorter and keyboardist Joe Zawinul formed Weather Report, a fusion band performing exhilarating original compositions. Pianist Chick Corea set up Return to Forever, an exuberant Latin-influenced band that started light and delicate but grew closer to hard rock in the 70s. Miles Davis’s sensational young drummer Tony Williams put together the raucous but more abstract Lifetime with guitarist John McLaughlin and Cream’s Jack Bruce. A cooler, more romantic fusion came with Pat Metheny, who not only proved that a guitar synthesizer could genuinely extend the eloquence of the instrument, but whose music never stopped suggesting a tousle-haired kid hitching a ride with a guitar on his back. Gil Evans, the painterly genius of jazz instrumentation who masterminded Birth of the Cool in the late 1940s, produced some uneven but often thrilling fusion sessions, even arranging some of Jimi Hendrix’s songs for a full-scale orchestra.

Some jazz players stayed on the fusion road until it wound all the way into pop—like guitarist George Benson, one of the finest improvisers since Wes Montgomery. Benson restricted his jazz playing to after-hours sessions once the soft funk and Nat King Cole-influenced vocals of his 1976 album Breezin’ changed his life. Fusion eventually suffered from its own self-importance, dependence on technical bravura, and repetitive formulae that cramped improvisation. But at its best fusion permanently transformed jazz, and in the 80s, all inhibitions about what jazz could appropriate as its own finally disappeared.

Ho Kan, Untitled, n.d.