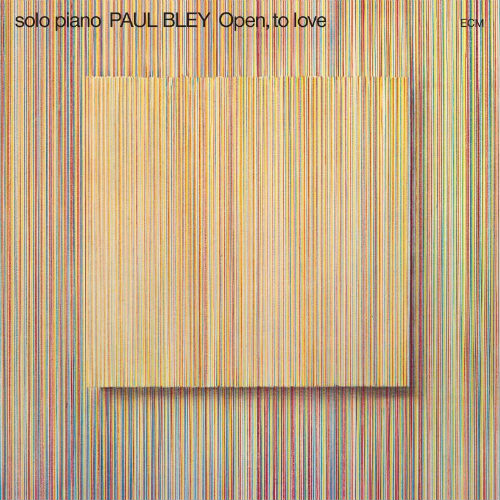

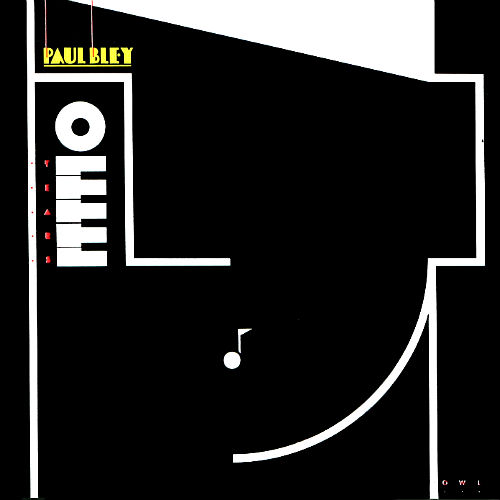

Paul Bley

PAUL BLEY: THE JAZZ PIANIST AS CALLIGRAPHER

Philippe Carles on Tears by Paul Bley (Solo Piano)

The following text constitutes the liner notes by Philippe Carles (Jazz Magazine) to the Paul Bley album Tears (Paris: Owl Records, 1983). Album available on Spotify (see Spotify section below).

Here themes are no longer mere ‘themes’; the gap between the premeditated and the improvised has never been smaller, and the listener is forced to ask himself whether his presence here is an act of indiscretion or of privilege; which ultimately comes down to the same thing, for here he finds himself side by side with the highly skilled prospector in the systematic yet random search for an entirely new language—each new strike reveals fragments of precious stones whose brilliance and richness are not always immediately obvious to the untrained eye. After finding dust, the occasional vein is struck, followed by a whole layer of resonant brilliance. Everything is accomplished in a single stroke of the artist, who, fashioning and sculpting sounds out of thin air, evokes the solitary and silent craftsmanship of the revered hermits and prophets of the keyboard.

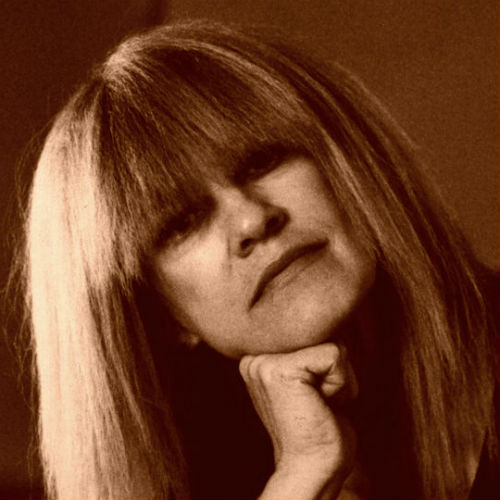

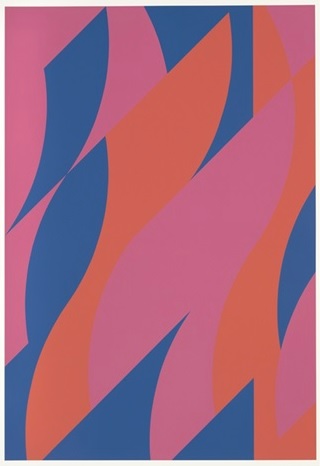

Bridget Riley, Shade, 1992

Bridget Riley, Large Fragment II, 2009

Rarely has the term ‘pieces’ enjoyed such exquisitely literal translation into musical terms, nor Dolphy’s hymn ‘Music Matador’ such resounding affirmation. But these are not ‘Selected Pieces’, all too often pressed into a conveniently bland and standardised mould by the radio programmer in his specious attempts to create a musical contrast. They are stamped through and through with the spontaneity emanating dreamlike from the fingertips of the artist and governed only by the rules of the ineluctable calligraphy of sound. Music in black and white, with delicate strokes on surfaces which conceal unsuspected depths, and lines and marks of overwhelming purity. Disparate elements are not merely juxtaposed, but each shade of colour and key to be found in the overall picture, however fleeting or allusive it might be, is struck in sharp definition. In a word, Paul Bley.

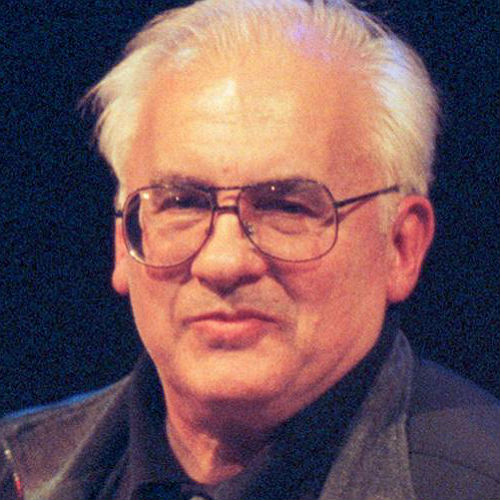

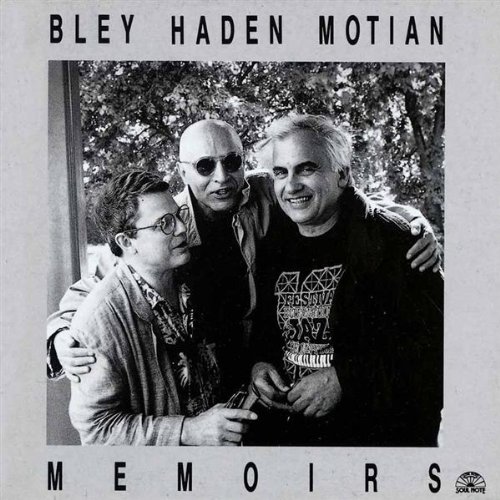

PAUL BLEY, CHARLIE HADEN & PAUL MOTIAN: EVOLUTION OF THE PIANO TRIO

Chris Sheridan on Memoirs

The following text constitutes the liner notes by Chris Sheridan (Jazz-FM Magazine) to the Paul Bley-Charlie Haden-Paul Motian album ‘Memoirs’ (Milan: Soul Note Records, 1990). Album available on Spotify (see Spotify section below).

Although Paul Bley’s work has the ice-cool, crystalline quality of finely-spun glass, this is nonetheless a hot trio. But, of course, it takes more than a little heat to fashion the finest glass and crystal, and this trio generates all the energy it needs. All three men heard here came to prominence at the cusp of one of the most important advances in piano trio playing, in the period between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s when bass and drums gained an equal voice with the previously dominant piano. It is hardly surprising, then, that Messrs Bley and Haden (graduates of the Ornette Coleman school) and Mr Motian (graduate of Bill Evans’) should together take the piano trio the next evolutionary step beyond that equilateralism.

Sarah Morris, 1980 (Rings), 2009

Sarah Morris, Rings, 2008

That step involves varying both the pulse and the melodic development. But it takes miraculous rapport to produce such tightly-knit and unified performances from the tools of freebop—improvising collectively in a manner that develops organically, from responses totally dependent on the impetus of each other’s playing. This does not mean to say that this music is constant polyphony; its members have much too much to contribute, with the result that its emotional and dynamic levels are satisfyingly varied. To this end, Mr Bley has always worked with challenging bass players—starting with Charles Mingus in 1953 and subsequently including Eddie Gomez, Dave Holland, Gary Peacock, Steve Swallow and, not least, Charlie Haden. Equally, he has also sought the support of thinking drummers whose talents usually exceed their reputations, like Pete LaRoca, Barry Altschul and, of course, Paul Motian.

Throughout his career, his approach to playing and recording has remained uncompromising. If his debut recording, with Mingus and Art Blakey, was a baptism of fire, he showed no sign of evading subsequent melting pots. In 1958, he led a quartet with Mr Haden and the vibist, Dave Pike; when Pike left, he was replaced by Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry. And, in 1964, Mr Bley was involved in the ‘October Revolution’ of so-called avant-garde jazz. With notable exceptions when he worked with Mingus (1959), George Russell (1960) and Sonny Rollins (1963-4), trios and duos have dominated Mr Bley’s working practices, the exceptionally musical threesome with Jimmy Giuffre demonstrating that not all need be conventionally composed. It was during this period that he finally abandoned the practice of playing chord-related improvisations, concentrating instead on a half-step chromaticism, laced by cross-rhythms that was gradually distilled into the fragmented lyricism now familiar.

Sarah Morris, 1984 (Rings), 2006

Sarah Morris, 1924 (Rings), 2004

Perhaps the best writer on Mr Bley, Jon Balleras, has summed up his contribution thus: ‘Bley might be designated a complete musical abstractionist. He thinks in melodic shapes and rhythmic thrusts rather than in key signatures, meters and conventional harmonic cadences. The effect is one of total freshness, of music that has never been played before and never will be heard again’ (Down Beat, 23/10/75 & 11/85). From such a description one can be confident that a performance like ‘Memoirs’ will not rest upon pure nostalgia. Indeed, Mr Bley’s arhythmic chromaticism insures against that, while its lyrical lustre rests on a poised use of space. It is a prime example of the manner in which vamps, rhythmic figures, melodic phrases, even tempo, all grow organically from the interaction of the participants’ ideas.

‘Monk’s Dream’ is a reminder that its composer’s unconventional approach to phrasing was a principal influence on Mr Bley’s post-Coleman development. It has an exceptional example of Mr Haden’s jogging bass, while the abrupt reappearance of the theme in a reprise hints at the impish sense of humour of both composer and pianist. ‘Dark Victory’ is a poignant ballad in which rippling piano figures grow from skittering percussion ones, and vice versa, paced by Mr Haden’s dry lyricism. As often in a Paul Bley album, Ornette Coleman’s vastly influential repertoire is represented, this time by ‘Latin Genetics’, an etiolated calypso of uncommon poignancy. ‘This Is the Hour’ revisits a familiar hymnal, but the emotions are expressed somewhat more drily. ‘Insanity’ sounds like one of those titles that Ornette Coleman might have penned. In fact, it is Mr Bley’s Glass Enclosure, a complex of unconventional musical patterns in which tempo is implied as rhythms and meters float, suspended over an acrostic of bass, drum and cymbal accents.

Sarah Morris, Lunar Eclipse (Rio), 2013

Sarah Morris, Japanese Bend (Knots), 2010

Mr Haden’s second contribution to the date, ‘New Flame’, expresses a dark ambiguity of emotion as though the undoubted warmth of its feelings are sensed only from a distance. ‘Sting-a-Ring’ opens with the brief off-centre chiming of a great clock, the rest of the performance blossoming entirely from the chattering figures of the drums that follow. Equally a rhythmic tour de force is the long Charlie Haden introduction to his own ‘Blues for Josh’, which provides Mr Bley with an opportunity to show how some of Bud Powell’s harmonic lessons have been distilled into the new milieu. Finally, a moodily querulous ‘Enough Is Enough’, except, of course, that, with musical creativity at this level, it is not. What this album demonstrates abundantly is that Paul Bley’s playing has an individuality that is constantly challenging and equally constantly rewarding. But it is an individuality that has largely proved inimitable (though its chromaticism has lately seen echo in the performances of Geri Allen), most notably perhaps via his unique perspectives on Ornette Coleman’s oeuvres.

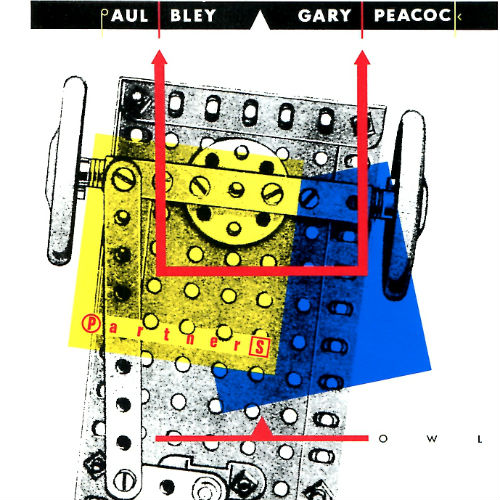

PAUL BLEY & GARY PEACOCK: THE OTHER IDEA OF JAZZ

Francis Marmande on Partners (Piano and Bass Duo)

The following text constitutes the liner notes by Francis Marmande to the Paul Bley-Gary Peacock album Partners (Paris: Owl Records, 1991). Album available on Spotify (see Spotify section below).

Draw up a list of musicians who’ve played with Paul Bley (piano) and Gary Peacock (bass) and it’s soon absolutely full up. The whole gamut of modern jazz is there, from Mingus to Miles, from Albert Ayler to Sonny Rollins. It would be possible to go on ad infinitum about the notion of modernity, but the simple fact remains: all those players who’ve redefined the bounds of their craft over the last thirty years, all those who’ve broken at some point with the commercial or industrial jazz establishment, all those who’ve chosen to overturn the aesthetic code of Charlie Parker which they’d become too attached to, they’re all there on the list, to a man. But this in itself is certainly no claim to glory, nor is it in any real sense a qualification. What can be said of Paul Bley and Gary Peacock is that they’ve continually mixed with every single player whose relationship to jazz has been essentially poetic: angry or self-effacing perhaps, but poetic.

William Fares, Untitled (AMS X), 2013

William Fares, Untitled (AMS V), 2013

What stands out in their approach and bonds them together is the delicacy of expression in their playing coupled with a dynamic use of space (interiority), a clear strand of intelligence, and an overall feel which springs out of friendship, and makes itself felt whether or not we know of their friendship. Since their first meeting in 1962, throughout their frequent appearances together, right up to the present duo (1990), it is friendship and closeness (note Annette Peacock’s role with Paul Bley) which have governed their passion.

Paul Bley’s first recording with Mingus was already marked by his declared wish to break with convention and set out in search of the new, and since then he has crossed paths with all the most significant bass players of the different eras he has been through: Scott LaFaro, Charlie Haden, Steve Swallow, Mark Levinson, Dave Holland, Niels-Hennig Orsted-Pedersen, etc. So his lasting partnership with Gary Peacock is doubly meaningful: firstly, in terms of the recent history of the instrument and its association with keyboards, as well as the individual roles which these links have both given rise to and liberated; secondly, in terms of the closeness of the two musicians and of the line of thought and imagination which they share. They have reached the point at which time stands still. Simply declaring your intention of breaking with the establishment doesn’t make you the author of a poetic act. You might have all the required technique and more besides, you may know all there is to know about your instrument and about spontaneous composition, you may well be a true professional at heart, but all that does not necessarily make a musician of you.

William Fares, Untitled (AMS I), 2013

William Fares, Untitled (SMA X), 2013

The lives they have led and the choices they have made along the way have prepared Paul Bley and Gary Peacock for all the eventualities of such a meeting, but this predisposition is the outcome of a great act of patience, like a meditation exercise. Because they have never compromised their talents in any way, choosing instead to remain open to the calling, in their maturity they are totally prepared for the leap into the unknown which the poetic act demands. Music, particularly improvised music, lends an air of drama and serenity to this leap. For unlike writing, say, or painting, you need a number of participants, and the fact that two people are involved does anything but make things simple.

With a duo improvising nothing slips by unnoticed. Either you strike the magic chord of a type of lovers’ empathy where you can anticipate your partner’s every intention, answering questions before they have even been asked, or else you run the risk of sinking into clichés and contrived chit-chat. Worst of all, of course, is the moment when rivalry, clashing egos and vulgar noise change a flowing dialogue into an idiotic exchange; clearly neither partner in this duo runs any of these risks, since their life’s work has been unconsciously devoted to making such risks impossible.

William Fares, Untitled (AMS II), 2013

William Fares, Untitled (SMA XII), 2013

It is this lifelong pursuit which gives their latest meeting an air of intimacy, of masterly lightness, of reciprocal listening, of full respect for silence, allowing us to go beyond the nimble dancing beauty of the music at its creation and listen in as privileged guests to one of the greatest modes of interaction that can take place between two men—this current of life. This is certainly why it has been the most intelligent and sensitive of men who have invented music. This is why such souls as Paul Bley and Gary Peacock join forces to invent music every day.

SPOTIFY – PAUL BLEY: TEARS | MEMOIRS | PARTNERS

Paul Bley: Tears (Solo Piano)

Bley, Haden, Motian: Memoirs (Piano Trio)

Bley & Peacock: Partners (Piano & Bass Duo)

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

PAUL BLEY IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 16

The beauty of a tone in decay, the grace of a sustained note dying: Cold, stark, spare and expansive, the brutal elegance of the music fills the room as you sit astride me on the rocking chair, your back to my chest, my wick in your wax.

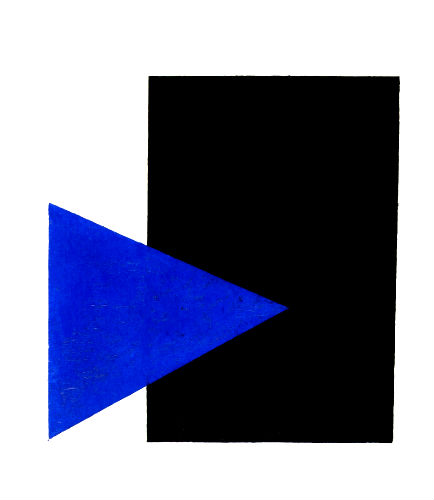

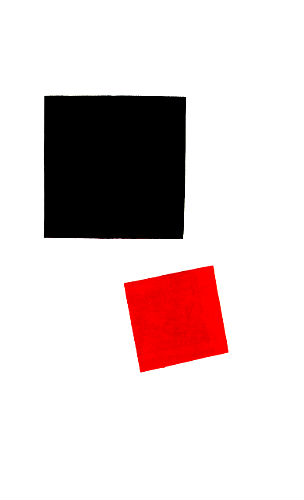

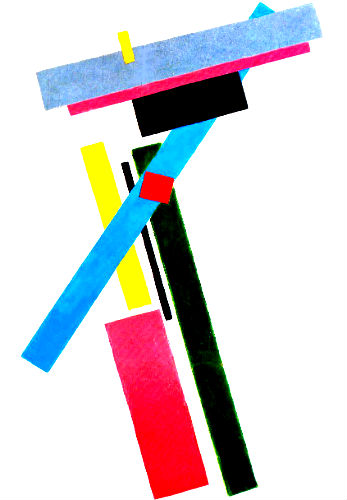

Kazimir Malevich, Four Squares, 1915

Kazimir Malevich, Black Rectangle, Blue Triangle, 1915

Imbued with silence, stark tones trace a calligraphy of stillness; under the pianistic fingers of Paul Bley, tentativeness and doubt become crystalline.

Stripping the harmonics from the melody, improvising upon a fragment, the pianist reverses the figure and ground of silence and sound.

Kazimir Malevich, Painterly Realism, 1915

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematism, 1915

Out from the ambient silence Paul Bley draws a melody; in the stark beauty of his elegant searching, every note weighed before it is played, we rock on the beechwood rockers of our aluminum rings.

Tightly pedalled chords and sparse right-hand figures stretch a tightrope between silence and sound: Constantly restoring his shifting balance, the pianist walks the wire.

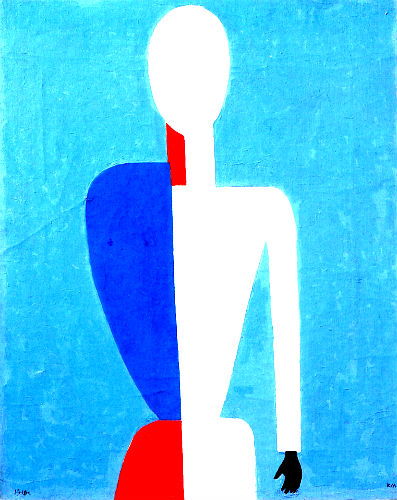

Kazimir Malevich, Prototype of a New Image, 1928-32

SPOTIFY: PAUL BLEY IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE TRACK IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

VIDEO: PAUL BLEY LIVE

Paul Bley | ‘Lucky’, 1973

Paul Bley | Clip from ‘Imagine the Sound’

Paul Bley | ‘Alrac’ (Carla), 1973