Sonny Rollins

MARTIN WILLIAMS ON SONNY ROLLINS: SPONTANEOUS ORCHESTRATION

From Martin Williams, The Jazz Tradition (Oxford University Press, 1983) pp. 183-93.

In the late summer of 1959 tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins stopped taking night club, concert, and record dates. Inevitably there was much gossip. It was said that he had decided to escape a round of work where both public adulation and constant playing were forcing him to repeat himself; that he was preparing some long compositions; that he had been intimidated by critical praise and by the close technical analysis of his recorded work; that he intended to reappear solo, as an unaccompanied improvising saxophonist. The last rumor was perhaps the most provocative. Rollins had frequently appeared without a pianist and—most important—in a sense had taken over the functions of orchestrator and orchestra all to himself.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Milagros, 2011

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Divertimento, 2009

In mid-1956, Sonny Rollins—formerly the capable, or perhaps the promising, jazz tenor saxophone soloist—had had a musical coming of age. Soon he was winning all the popularity polls, and his records were being reviewed as examples of ‘uninhibited passion,’ ‘inner compulsion,’ etc. But descriptions of the impact and sureness of his playing tell only part of the story, and the rest of the story makes Rollins a unique hornman in the history of jazz.

By the mid-fifties, modern jazz was no longer faced with discovering or testing its basic musical language but with establishing some sort of synthesis within the idiom, with the task of ordering its materials which, for earlier styles, had been done by Jelly Roll Morton in the twenties and Duke Ellington in the late thirties. In the fifties, the problem was met, foremost, by Thelonious Monk; by pianist-composer John Lewis with the Modern Jazz Quartet; and by Sonny Rollins as an improvising saxophonist.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Día de los Muertos, 2014

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Pablo et Wilfredd: un rendezvous, 2014

In one sense the history of the last thirty years in jazz might be written in terms of the length of the solos that its horn players have been able to sustain. Certainly one contribution of bebop was that its best players (but only its best) could undertake longer improvisations which offered a flow of musical ideas without falling into honking or growling banalities. I do not mean that the younger players of the forties were either the first or the only jazz musicians to be able to do this, only that for some of them a sustained solo was a primary concern. However, a great deal of extended soloing in jazz has had the air of an endurance feat—a player tries to keep going with as little repetition as possible. But when the ideas are original and are imaginatively handled, such playing can have virtues of its own. However, a hornman’s best solos are apt to be continuously developing linear inventions. Sonny Rollins has recorded long solos which, in quality and approach, go beyond good soloist’s form and amount almost to sustained orchestrations.

Previously, jazz pianists have shown such concern with larger form in improvising. Some examples (a random sampling) are Jelly Roll Morton’s solo on Hyena Stomp, Willie ‘the Lion’ Smith’s Squeeze Me, and Fats Waller’s Numb Fumblin’. But of course many pianists have thought formally and orchestrally, even some simple blues men—Jimmy Yancey in How Long #2 and State Street Special—have exceptionally cohesive designs.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, We All Belong, 2013

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Mad Madrigal, 2007

Sonny Rollins’s early records indicate his later developments only in retrospect. At the time they seemed the work of a talented player, in more or less the style of the time, a style probably best exhibited in Dexter Gordon’s work. This style variously combined the robust, extroverted manner of Coleman Hawkins (but without his vibrato) with many of the approaches to melody, rhythm, and asymmetry of phrasing of Lester Young, plus some of Charlie Parker’s ideas as well.

One can hear the young Rollins of 1949 with a Bud Powell group on Bouncin’ with Bud, Wail, etc., and the release of some alternate takes from this session shows that Rollins was really improvising, offering a rather different solo on each performance of each piece. Most of the other players involved had had experience in big bands. Rollins had not; indeed his first job with a regularly working group did not come until he joined Max Roach in late 1955. Big band work can teach lessons of discipline and terseness in short solos, and lessons of group precision and responsiveness. Rollins has learned some of those lessons, but he has surmounted not having learned others.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Calypso Bay, 2017

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Perpetual Construction, 2010

Rollins had his first record date on his own in 1951. Slow Boat to China (one of several unexpected pop vehicles to come) and Shadrack show a relaxed sureness of phrasing and rhythm, and This Love of Mine an increase in saxophone technique. Mambo Bounce is (significantly, I think) a twelve-bar blues. It includes four ad lib choruses by Rollins, only the second of which uses ordinary ideas. More important, the solo has only one Parkeresque flurry of short notes. Parker himself often used such runs for contrast or variety in his solos; some of his followers might throw them in almost anywhere on impulse. Rollins usually uses such double-time phrases sparsely, and in Mambo Bounce the virtuoso run appears in his fourth improvised chorus, where it becomes the climax of his solo. A happy accident? Perhaps. But I wonder, in view of his later work. Perhaps it was conscious and deliberate, but more likely it was the result of personal artistic intuition. It suggests one way that the technical resources of modern jazz improvising might be used structurally. Again, the hint might have come from Hawkins; he was one player of his generation who brought off long solos, and his usual manner was to build in technical complexity.

Sonny Rollins continued to acquire more techniques, learned to use them with more relaxation; as his sound and attack became increasingly personal, his ability to swing reached near-perfection. He also played with Thelonious Monk, and the experience was surely important to his development, And, in mid-1954, he participated in a very good Miles Davis recording session to which he contributed three interesting pieces: Airegin, Oleo (probably under the inspiration of such Parker lines as Scrapple from the Apple, but again renewing the I Got Rhythm chords), and Doxy, a modern return to the sixteen-bar patterns of the twenties.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, A Good Face for Bad Times, 2015

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Who Can Stop the Rain?, 2017

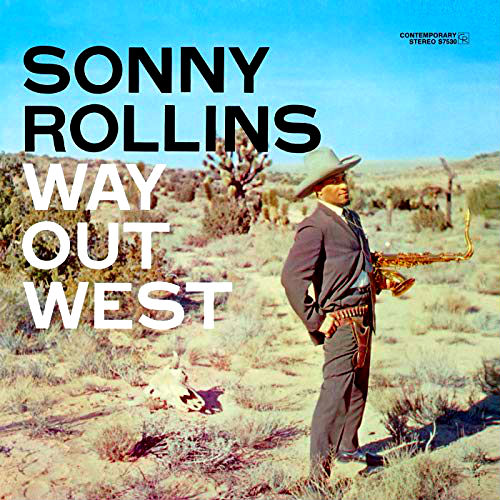

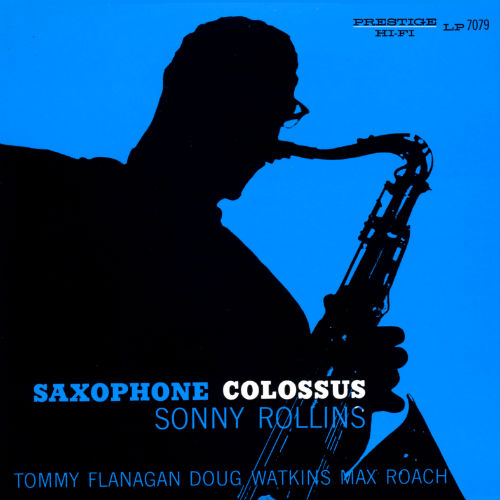

A bit later there was Tenor Madness on which John Coltrane joined Rollins. Here is relatively early Coltrane, to be sure, but he shows the harmonic searching of the highly sophisticated, vertical player he later became. In the placing and accenting of his short notes, Coltrane is already identifiably Coltrane. Rollins is a confident master of his own materials and he climaxes his own section with a telling moment of technical complexity, just as he had on Mambo Bounce. But the LPs which made Rollins’s public reputation were ‘Saxophone Colossus’ (done in June 1956) and ‘Way Out West’ (March 1957). The latter is a collection, largely of pop ‘Western’ songs in which Rollins plays with remarkable power and ease. Some reviewers heard ‘anger’ or ‘aggression’ in his saxophone sound. There is much humor to be sure; there is parody and even sardonic comedy. And surely Rollins’s firm, confident phrasing, his masterful dynamics and excellent use of the range of his horn (from firm, cello-like low notes to bold cries in upper range), surely these things balance the ‘negative’ emotion in his playing. Also on that record there is more than a hint that he was taking a cue from the airy, open phrasing of Lester Young’s later work.

Another aspect of the ‘Way Out West’ LP is the masterful way that Rollins shows he had absorbed ideas from Monk on how to get inside a theme, abstract it, distill its essence, perceive its implications, and use it as a basis for variations—without merely embellishing it decoratively or abandoning it for improvisation based only on its chords. Besides making public appearances with him, Rollins has several times recorded with Monk. And one might note that, for example, on their version of Bemsha Swing Rollins begins his solo with the last idea that Monk had played in his section, and that, as Rollins’s line gets more complex, Monk reintroduces orderly reminders and hints of the theme beneath him. By 1957 Rollins had moved so far along as a kind of one-man orchestra that on the title piece of ‘Way Out West’ he returns for his second solo with a spontaneous imitation of Shelly Manne’s drum patterns.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, No Man’s Land, 2015

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, April in Paris, 2014

Blue 7 from ‘Saxophone Colossus’ is a masterpiece, hence it is the kind of performance that one hears anew with each listening and that is difficult to discuss and describe. Its heritage, as Gunther Schuller pointed out in his detailed analysis, includes Monk’s Misterioso and the Miles Davis-Sonny Rollins Vierd Blues. It begins with an almost nonchalant and tranquil bass line by Doug Watkins. Upon this, Rollins states the theme, a simple blues line that has a strong individual character. Yet it is also suspended in an ambiguous bitonality. The piano’s entrance behind Rollins assigns it a specific key, and Rollins begins to explore its implied brilliance expertly. The performance builds from one phrase to the next, yet that structure is so logical and so comprehensive, with its details so subtly in place, that it is as if Rollins had not made it up as he went along, but had conceived it whole from the beginning. Max Roach has said that he and Rollins both had in mind Monk’s admonition: Why don’t we use the melody? Why do we throw it away after the first chorus and use only the chords?

Almost everything that Rollins plays on Blue 7 is based on his opening theme, but Rollins also structures and builds—he even builds on his elaborations and his brief interpolations, and he is not afraid of an almost direct recapitulation of his theme at one point during the performance. The order and logic of the performance extends also to Roach’s solo, based almost entirely on a triplet figure and a roll, while Tommy Flanagan’s non-thematic piano solo serves as a kind of effectively contrasting, lyric interlude. Blue 7 is one of those rare performances which almost anyone can appreciate immediately, I think—anyone, from the novice who wants to know where the melody is, to the sympathetic classicist who can appreciate how highly developed the jazzman’s art has become.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Blue Abstract, n.d.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Balance de un día redondo, 1980

Blue 7 is one of the great pleasures of recorded jazz, but its elaborations and distillations of theme do not represent Rollins’s only approach to extended improvised form. Another is the one he hinted at in Mambo Bounce, but he has never recorded it in the masterful way he has used it in public. In this approach Rollins would first state his theme, then gradually simplify until he was playing only a scant outline. Then he would gradually slip away from it and invent new melodies—at first very simple ones—out of the chord structure of the piece. He would proceed to develop these: his note values getting shorter, his melodic lines longer and their contours more complex. When he had built such a solo over several choruses to a peak of melodic and rhythmic virtuosity, he would gradually reverse himself, return to simpler melodies, to fewer and longer notes. Soon, one would realize, Rollins had begun to resketch his initial theme with certain suggestive notes and phrases, and finally he would restore it completely to a full recapitulation.

My account may make Rollins’s performances seem mechanical. Of course his power and sureness alone might prevent such playing from being mechanical, but his spontaneous designs were never so pat as a general description is apt to imply. Long runs of notes are interspersed with short ones and even with short, staccato, humorously delivered single notes. Fragments of the theme are heard in otherwise harmonic variations. Brief virtuoso lines appear in otherwise simple choruses. But these form patterns of prediction and echo in an overall structure, and the way to hear a good Rollins performance is always to try to hear it whole.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Noche kikapoo, n.d.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Alba, 1981

There is another Rollins recording which is still differently structured, but which is again based on comparable material, Blues for Philly Joe. On it Rollins plays a kind of free, spontaneous blues rondo. Using A to indicate Rollins’s main theme, A plus a numeral to indicate thematic variations, and other letters to indicate variations that are not thematic, one might outline the performance roughly this way: A | A | A-1 | A-2 | A-3 | B | C | A-4 | D | D-1 | E (A-5?) | Wynton Kelly’s piano solo | exchange of four-bar phrases with drummer Philly Joe Jones | A (A-6?) | A.

There are several fascinating details which such an outline can’t indicate. For example, the new material Rollins introduces in A-1 appears again in variation in A-2, thus tying these two choruses together. Subsequently this double-chorus idea is echoed at D and D-1, at approximately the middle of the piece, and again at the end of the piece. A-3 is almost, but not quite, a non-thematic chorus; it is as if Rollins’s strong departures from his theme were preparing our ears for B, which is far enough away to be called non-thematic. Chorus E has strong reminders of the main theme toward the end, and is therefore part E and part A-5. Rollins’s four-bar phrases in exchange with Joe Jones are sometimes melodic and sometimes percussive, as might befit exchanges with a drummer. The two final saxophone choruses are thematic, but neither is an absolute restatement of the A theme, although the final chorus is closer. Again, let me warn that an outline like this one of a spontaneous performance is apt to make Rollins’s playing seem calculated and mechanical when it is anything but that. However, his sense of order is there—as natural and spontaneous as any other aspect of his playing—and it is a major part of his aesthetic achievement. (Rollins can be outstanding also at non-thematic, motive-oriented solos: In Your Own Sweet Way with Miles Davis, for example.)

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Untitled, 1994

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Un día radiante, 1989

The Rollins who returned to public performance in the fall of 1961 was the same Rollins, only more so. One’s memory of that Rollins is a memory of performances which nostalgia might exaggerate but which exact memory could obscure. Again there were the long performances, which Rollins seemed to conceive as entities, but which also develop with internal logic, phrase by phrase. There were also extended cadenzas in which Rollins would rapidly execute an entire thirty-two bar theme on a series of two or three chords spontaneously offered him by his pianist, altering only those notes necessary to fit each chord in succession.

I wrote the following account in Down Beat of a Rollins concert held in mid-1962: ‘For Rollins, the promise was fulfilled brilliantly. From his opening choruses on Three Little Words, it was apparent that Rollins was going to play with commanding authority, invention, and a deep humor which even included a healthy self-parody. His masterwork of the evening was a cadenza on Love Letters, several out of tempo choruses of virtuosity in imagination, execution, and a kind of truly artistic bravura that jazz has not known since the Louis Armstrong of the early thirties. The performance included some wild interpolations, several of which Rollins managed to fit in by a last minute and wittily unexpected alteration of a note or two. To my ear, he did not once lose his way, although a couple of times he did lose guitarist Jim Hall—and that is nearly impossible to do for Jim Hall has one of the quickest harmonic ears there is. Rollins’s final piece was a kind of extemporaneous orchestration on If Ever I Would Leave You in which he became brass, reed, and rhythm section, tenor soloist, and Latin percussionist, all at once and always with musical logic.’

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Absract, 1980

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Ojos de la intuición, 1981

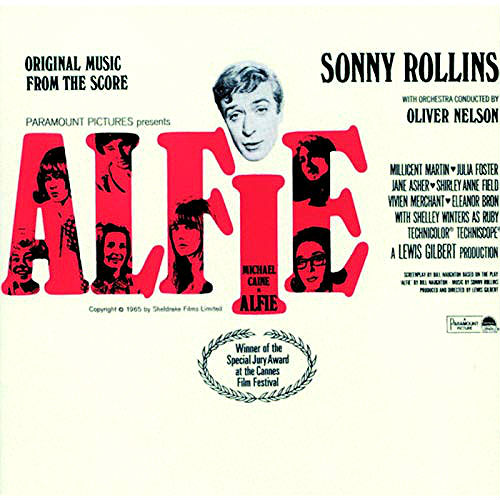

Again, one is left with the frustration that Rollins’s recordings do not show the level of his achievements in clubs and concerts. There is a recording of If Ever I Would Leave You; it is very good indeed, but it is a shadow of the masterful performance described above. Even the ‘live’ Rollins can be a frustration. ‘A Night at the Village Vanguard,’ recorded for Blue Note, is a fine example of generally sustained high-level playing, but it does not have the brilliance of Rollins ‘live’ at his best. The other side of the frustration is represented on the LP which appeared in 1978 as ‘There’ll Never Be Another You,’ and offered a June 1965 concert in the Museum of Modern Art’s Sculpture Garden. Here is Rollins the passionate, raw, spontaneous, and almost (but not quite) eccentric improviser, ending one solo only to begin another on the same piece, cajoling his sidemen, shifting keys and tempos without warning, walking away from the microphone so that an assertively begun coda is heard almost as a faint echo—and leaving us with some tantalizing unfinished documents, particularly on There Will Never Be Another You and Three Little Words. That latter piece was something of a Rollins specialty in the mid-sixties, and there is a polished studio version from July 1965. But the classic Rollins from that decade is surely his fine set of variations on Alfie’s Theme (1966) with a sparely used studio orchestra.

I do not find Rollins’s (or anyone else’s) flirtings with the static rhythms of rock and roll convincing, but the 1970s did see him recording a convincing ‘modal’ improvisation called Keep Hold of Yourself. (Rollins’s rather high-handed treatment of a chord progression or two on the interesting, and previously underrated, Freedom Suite perhaps forecast his ability to handle such a challenge.) And there is Skylark from 1971, probably Rollins’s masterpiece of sustaining slow balladry, with two fascinating cadenzas (the opening one, more than fascinating). Skylark is a kind of spontaneous sonata-étude, if you will, and the kind of performance that makes one wonder again if jazz improvisation has not made possible the highest level of accomplishment in contemporary music.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Birds on Black, n.d.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Conexión luminosa, 1983

To return to the earlier Rollins, one of the most instructive comparisons in recorded jazz, and one of the best indications of another aspect of Rollins’s position in its history, comes about because several important players have made versions of Cherokee and variants thereof. There are records by tenor saxophonist Don Byas, by Charlie Parker (as Koko), and by Rollins (as B. Quick). At least by the mid-forties Byas was perhaps as sophisticated harmonically as was Rollins at his peak—witness Byas’ version of I Got Rhythm. Melodically and rhythmically Byas echoed Hawkins; he was an arpeggio player with a rather deliberate and regular way of phrasing. Accordingly, when Byas plays an up-tempo Cherokee, his solo is so filled with notes that it seems a virtuoso display, and in an apparent melodic despair he is soon merely reiterating the theme. Parker of course broke up his phrases and his rhythm with such brilliant variety that he was able to establish a continuous, easy linear invention, avoiding Byas’ effect of a cluttered desperation of notes. Rollins’s B. Quick choruses, however, seem to be filling in again with notes. Of course this is partly because Rollins does not have Parker’s rhythmic imagination (what jazzman has?) but, symbolically at least, it means that Rollins’s maturity and his major contributions of improvised form came near the end of the great period of jazz which began with Charlie Parker.

SONNY ROLLINS IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 13

Around her wrist, stacked between bands of woven silver, a serpent flashes its emerald eyes.

̶ Thank you, Maya. I’ll remember that.

She sips her drink. Suddenly you break into song:

̶̶ ‘On a sidewalk, one Sunday morning, lies a body just bleeding life.’

Maya joins you:

̶̶ ‘And someone’s sneaking round a corner, could that someone be Mack the Knife?’

Relaxed and poised, Sonny Rollins, the Saxophone Colossus, does justice to the sardonic menace of Brecht and Weill’s vision. Listen! Brilliantly inventive, with swirling runs and staccato moans he invites us to syncopate the possible. Accepting the invitation, your body sways with Maya’s: You’re ready for anything.

̶ ‘Bet you Mackie’s back in town’, you sing together.

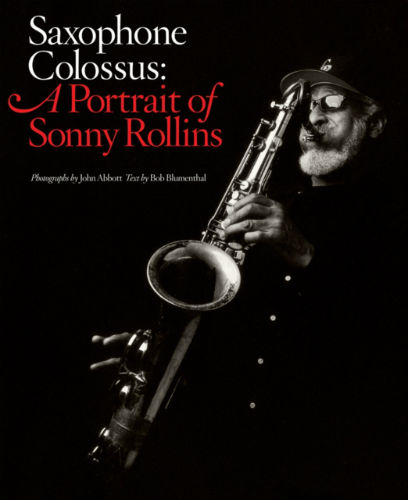

Sonny Rollins | Photo: Jan Persson

SPOTIFY: THREE SONNY ROLLINS ALBUMS

Sonny Rollins | Way Out West

Sonny Rollins | Saxophone Colossus

Sonny Rollins | Alfie

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

VIDEO: SONNY ROLLINS LIVE

Sonny Rollins Quartet | Live in Denmark, 1968

Sonny Rollins Sextet | Live in Munich, 1992

Sonny Rollins Trio | Live in Europe, 1959