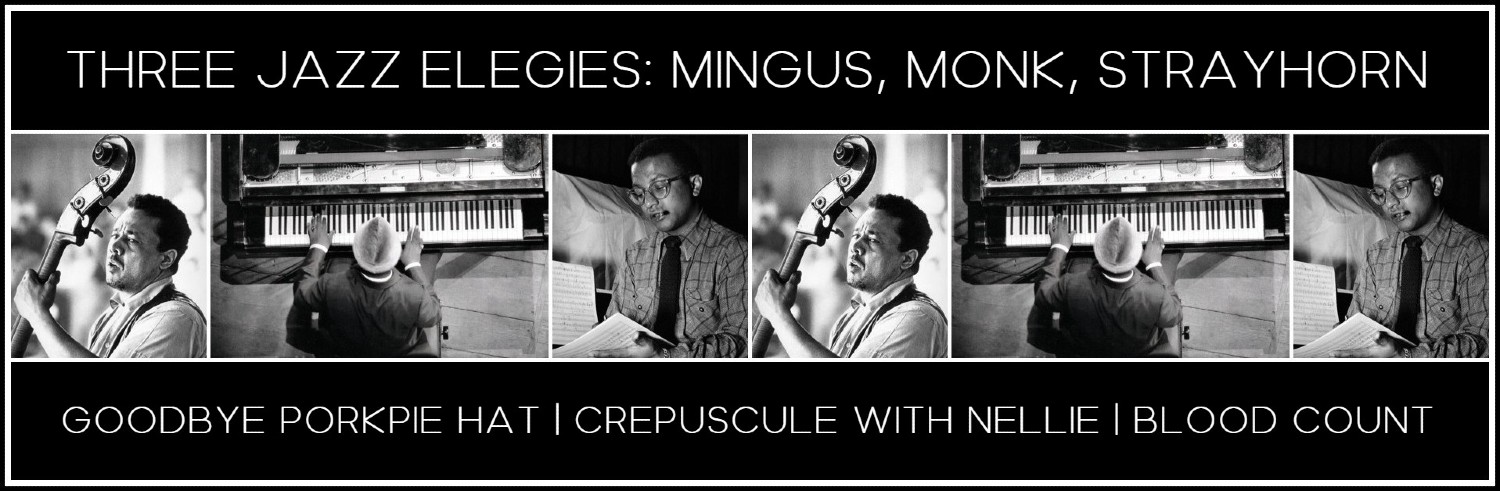

Thelonious Monk

MONK’S HANDS: LAURENT DE WILDE ON THELONIOUS MONK

Posted by kind permission of Laurent de Wilde

From Laurent de Wilde, Monk, translated by Jonathan Dickinson (NY: Marlowe and Company, 1997).

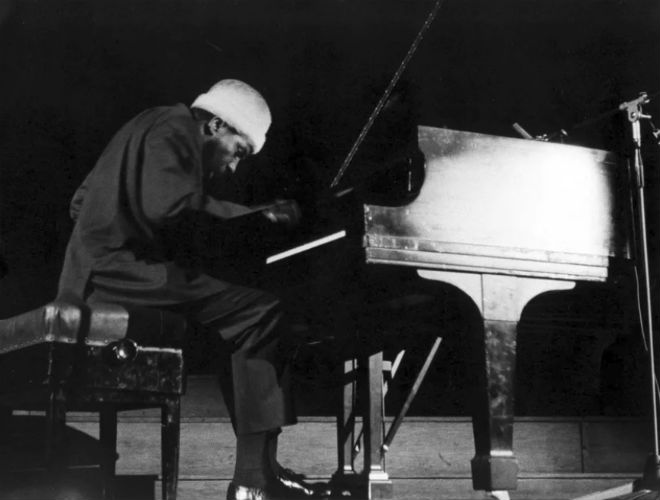

Thelonious Monk | Photo: Francis Wolff

Hands. A pianist’s hands are objects of universal fetishism. Like the nose of a wine taster, or the biceps of a boxer. And yet a pianist also plays with his wrists, his neck, his breathing and his elbows. And, of course, his feet. Monk’s feet inevitably drew the attention of all the cameramen who filmed him in action. They seemed to have a life of their own, and reacted to his music in flourishes. His feet expressed all the tension that was released above them, and then buried those sounds into the ground which carried them. And his feet beat out the joyous tempo of the rough, exquisite music he was playing. But his hands were what really won the prize. Thelonious didn’t really have what you could call pianist’s hands.

They were not the magnificent hands of a pianist like Keith Jarrett. Jarrett’s hands are unique—supple and muscular, agile and powerful, like those of an athlete; sometimes hesitant on the keyboard, but in such an instinctive way that they never lose their assurance and direction. Nor were they like the hands of Bud, with their fabulous spatulate fingers which caressed the keys instead of striking them, with the meat of his fingers, without the least sign of effort or fatigue. Or Oscar Peterson, with his immense hands which seem to span half the keyboard. Or hands like those of Bill Evans—perfectly attentive. no superfluous movement, as if he were extracting a thin but constant flow of precious vital fluid.

Thelonious Monk | Photo: Francis Wolff

Thelonious Monk | Photo: Francis Wolff

No. Monk’s hands were more like palms divided into five parts. Each fingertip seemed to be all nail. His hands were astoundingly small in relation to his size. His eminently personal technique was said to have originated because of this. He even had a hard time playing tenths on the piano. That interval, of about 9 inches, is the standard for measuring if a pianist is lucky or not.

Monk’s hands weren’t designed for making a fist, and an invisible force seemed to stiffen them straight out. And his lingers didn’t have much of a spread. They liked to stay close together, for anything could happen—they could get stuck with a cigarette, a huge ring, or a glass of whiskey, picking up things like a rake. On the keys, they produced results which were unimaginable. One portion of the film Straight, No Chaser shows Monk during a piano solo, pull a handkerchief from his pocket, take his cigarette from his mouth, wipe his sweat-soaked brow (with the cigarette still in the other hand), place the cigarette on the edge of the piano (where, of course, it burned the wood), then put the handkerchief down, improvising all the while, with handkerchief and cigarette in hand according to where he was in the changes to ‘Round Midnight’! He could do anything with those hands!

His hands were not strictly reserved for the piano, like the mannered hands of a diva. Before hitting the keys, they carried with them a space, a life, a void: bang! The field of action of Monk’s hands was much more than the black and white surfaces of the eight octaves! In fact, it wasn’t a surface, but a volume! One yard above, one yard to the side, one in front and one behind!

Standing, sitting, leaning forward, not like Jarrett whose hands never leave the keyboard, but rather attacking the keys from a distance, from high above, as only he could do. The notes he played must have weighed over two hundred pounds! Bang! Bang! Or sometimes they weighed only a few ounces and were so faint that the transcribers refer to them as ‘ghost notes’—phantom notes that come to haunt the keyboard from time to time.

Sometimes he’d hit a chord on the keyboard, then immediately raise his arms as if he had received a jolt. Then he’d stare at the piano with a perplexed air as if to say, ‘Hmm, that’s weird; this thing sounds great!’. He always looked at his hands. Usually a piano player looks straight ahead and he can keep on playing when the lights go out. Bud never looked at his hands. He felt the keyboard and saw it in his mind, and touched it but never looked at it. In all the years that musicians have been surveying that yard and a half of notes on the piano keyboard, you’d think it would be perfectly familiar. But Monk would try some moves, cross his arms, then smash a note. He was always ready for something new to turn up. It was truly incredible the way he was able to maintain that contagious sense of naive amazement toward his instrument, right up to the end. As if the piano played all by itself. Or as if he made it speak in an unpredictable way, even for himself, by inventing rules as he went along. But even when hesitating, he always had a magnificent self-confidence. He always aimed at something specific, particularly the last note of an arpeggio. A couple of notes could disappear along the way, becoming ghosts, but never the last one!

With Monk, you are always heading somewhere. And when you get there, it’s usually a big surprise.

Thelonious Monk | Brussels, 1964

A MUSICAL BODY: PETER SZENDY ON THELONIOUS MONK

From Peter Szendy, Phantom Limbs: On Musical Bodies, tr. Will Bishop (NY: Fordham University Press, 2016)

Monk—Thelonious Sphere Monk—is probably the musician who, more than any other, experienced distance. The distance from himself to himself that he constantly experienced and made resonate on a keyboard.

This is what we hear when he plays alone. His left hand moves imperturbably in old stride style: a bass note on the first beat, a chord stuck onto the second, and so on and so forth, infinitely, in tireless step. While his right hand is by turns agile, jerky, dissonant, fantastical, insistent, repetitive, angular, even voluntarily clumsy and gauche. Always unpredictable, it seems to ignore the other one, the left hand, the one over there that remains so regular and rigid and straight, almost indifferent.

Between them, there is more than just stylistic dissonance: a whole world. An attentive witness—a pianist who has listened to him a lot—has written, ‘The left hand was classic, and the right was modern. Take away the left hand and there would be the Monk of twenty years later. Remove the right, and we would be back to the jazz of twenty years earlier’ (Laurent de Wilde, Monk, trans. Jonathan Dickinson, Marlowe & Co. 1997, p. 20).

If I count right, that makes forty years between these two playing hands. Forty years’ distance, here, now, in the same instant. And forty years, in the history of jazz, is already quite a lot.

I am sometimes even tempted to imagine that, between Monk’s two hands, there may be centuries. Perhaps millennia, between his occasionally very awkward right hand and his always straight left hand.

THINKING OUT LOUD: QUINCY JONES & VALERIE WILMER ON THELONIOUS MONK

From Valerie Wilmer, Jazz People (NY: Da Capo Press, 1977), p. 44-45

QUINCY JONES

Thelonious is one of the main influences in modern jazz composition, but he is not familiar with many classical works, or with much life outside himself, and I think because of this he did not create on a contrived or inhibited basis.

Quincy Jones, quoted in Valerie Wilmer, Jazz People (NY: Da Capo Press, 1977), p. 44

VALERIE WILMER

When Monk plays, you can almost hear him thinking out loud as he selects a note and carefully considers its effect before adding a couple of others, judiciously chosen. Although he received a conventional formal training, Monk plays ‘incorrectly’, with his fingers held parallel to the keyboard. Was he ever taught to hold his hands in the formal manner? ‘That’s how you’re supposed to?’ he asked, feigning wide-eyed surprise. ‘I hold them any way I feel like holding ‘em. I hit the piano with my elbow sometimes because of a certain sound I want to hear, certain chords. You can’t hit that many notes with your hands.’

Valerie Wilmer, Jazz People (NY: Da Capo Press, 1977), p. 44-45

THELONIOUS MONK IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 13

As she sips her sweet and dry vermouth, her gin and orange juice, Thelonius Monk comes in to give his version of ‘It Don’t Mean a Thing if it Ain’t Got That Swing’. The catchy phrase has you hooked, the syncopation sets you swinging.

Monk | Pannonica de Koenigswarter

SPOTIFY: LAURENT DE WILDE PLAYS THELONIOUS MONK

Laurent de Wilde | The Back Burner

Laurent de Wilde: New Monk Trio

Laurent de Wilde: Spoon-a-Rhythm

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

SPOTIFY: THREE THELONIOUS MONK ALBUMS

Thelonious Monk | Brilliant Corners

Thelonious Monk Plays Duke Ellington

Thelonious Monk | Monk’s Music

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

THELONIOUS MONK: FOUR BOOKS

VIDEO: THELONIOUS MONK LIVE

Thelonious Monk Quartet | Tokyo, 1963

Thelonious Monk | Berlin, 1969

Thelonious Monk Quartet | Norway & Denmark, 1966