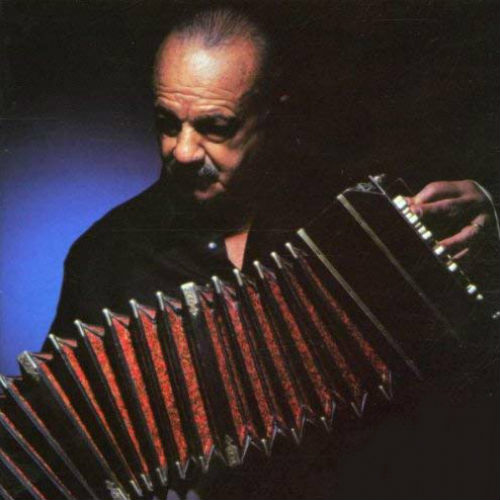

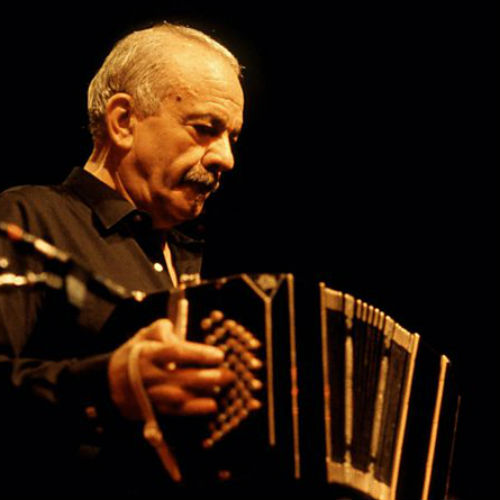

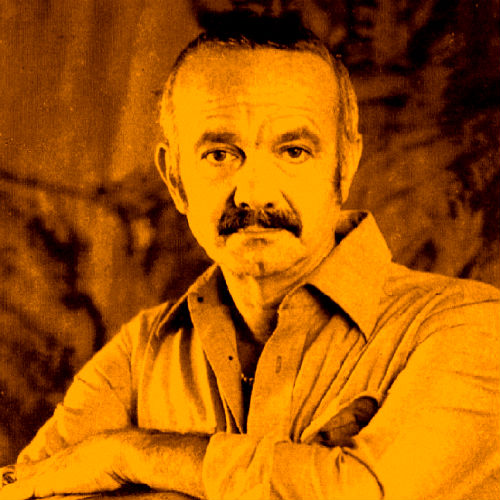

Astor Piazzolla

ASTOR PIAZZOLLA: TANGO ZERO HOUR

Fernando Gonzalez on ‘Tango Zero Hour’

The following text constitutes the liner notes to the 1998 Nonesuch Records re-release of Astor Piazzolla’s 1986 album, Tango Zero Hour.

Astor Piazzolla imagined la hora cero as the time after midnight, ‘an hour of absolute end and absolute beginning.’ It was not by chance, then, that early in his career, he titled one of his break-through pieces Buenos Aires Hora Cero. It could not have been by chance that, as he was entering his autumn days, he called an album that summed up decades of hard work and carried deep personal hopes and professional expectations, Tango: Zero Hour. By the mid-1980s, Astor Piazzolla had long been celebrated in Europe, and finally, grudgingly, been given the respect he deserved in his native Argentina. The irony was that despite his American upbringing, recognition in the United States still eluded him.

Adriana Gibello, The Air that Breathes the Night, 2016

Adriana Gibello, Through the Shadows, 2013

In 1921, when Piazzolla was three, his family moved to New York from Mar del Plata, a seaside resort city south of Buenos Aires. They stayed in New York, with a brief interlude, until 1936. It held the memories of his childhood—street-fights, Cab Calloway heard from the sidewalk outside a Harlem night club, and the Italian solfege teacher who taught him the secrets of making spaghetti sauce. While living in New York, his father gave him his first bandoneon, the button squeezebox that is the quintessential tango instrument. It was also in New York where, more than twenty years later, as a grown man, a musician just trying to make a name for himself and feed his family, enduring what he once called ‘the hardest three years of my life,’ that Piazzolla learned of his father’s death and composed his most famous work, the moving Adios Nonino.

Piazzolla rarely visited New York after leaving the city in 1960. When he returned briefly to record Zero Hour twenty six years later, he was musically at a peak. He had distilled years of apprenticeship as tanguista, the lessons learned from his classical teachers, his fascination for jazz, and the memories of a thousand bruising battles as a one-man tango avant-garde into a music that was sophisticated, profound and emotionally direct. He also had an extraordinary instrument with which to play it, for at Zero Hour, he was into a ten-year run with The New Tango Quintet.

Adriana Gibello, Behind the Door Hidden, 2013

Adriana Gibello, It Seems an Oversight, 2013

His Octeto Buenos Aires, organized in 1955 after he returned to Buenos Aires from Paris, energized by his studies with Nadia Boulanger and his encounter with Gerry Mulligan’s Octet, marked the great divide between traditional tango and what came to be known as Nuevo Tango. Piazzolla’s first quintet, which remained loosely together from 1960 to 1970, pushed the boundaries of Nuevo Tango as quickly as it established them. His short-lived Conjunto 9 (1971-72)—in fact a string quartet and quintet featuring a trap drummer—sparked his most elaborate writing for small ensemble. But the New Tango Quintet, convened in 1978, was in a class by itself. Having come together through a mix of vision and chance, the quintet on this recording features Piazzolla on bandoneon, Fernando Suarez Paz on violin, Pablo Ziegler on piano, Horacio Malvicino, Sr. on guitar and Héctor Console on bass.

It was a fortunate mix. A jazz player at heart, Malvicino had once injected jazz-style improvisation into the music of the Octeto Buenos Aires—a revolution within a revolution in tango. With a background in both jazz and classical music, Ziegler was an ideal partner. ‘The difference in this group,’ Malvicino recalled recently, ‘was that Astor for the first time had a pianist with a jazz background. Ziegler was not an authentic tanguero, but a guy who learned a lot with Astor and became a tanguero—whether he wanted to or not.’ The reserved Console, schooled on tango and classical music, was the foundation of the quintet, rock solid but also nimble and exceptionally sensitive. The classically trained Suarez Paz, in what had traditionally been the star role in Piazzolla’s group, proved to be a brilliant technician with heart to match and grit to spare.

Adriana Gibello, Secret of Summer, 2012

Adriana Gibello, Between Fire, 2015

By the time The New Tango Quintet went into the studio, it had assumed the spirit of its leader—it was cosmopolitan and streetwise, erudite but also passionate, elegant yet tough. In the span of one piece, the quintet could suggest a chamber group one moment, and a rugged, Saturday night neighborhood tango dance band the next. As Ziegler explains, ‘By the time we recorded Zero Hour we knew each other by smell, and something had taken shape well beyond the scores. We all got along very well. We were very tight personally, we loved the music, and Astor loved the group. He loved his musicians. That’s what you hear. That and that stuff in the cracks of the music, the passion, the grime that came to the surface over years of playing together.’ To this Malvicino adds, ‘It was clear this was not just another record. This was the great American adventure, the conquering of America.’

These nuances might have been lost on some producers, but in Kip Hanrahan, Piazzolla found someone who could not only hear them, but appreciate and capture them. Initially, the Bronx-born Hanrahan might have seemed a curious choice. He had an adventurous but small label, American Clavé, and was best known as a composer of knotty avant-ethnic fusion and a sui generis bandleader. (Coincidentally, the offices of American Clavé were just blocks away from where Piazzolla had lived as a child.) According to Malvicino, ‘Astor was disenchanted with the big labels. He felt they had not treated him with respect. Kip loved Piazzolla. He had a tremendous admiration, a passion, for everything Piazzolla, and knew his work from the days of his orquesta tipica (traditional tango orchestra). Kip is not your average guy, he might not be easy sometimes, but he is great fun, has a great sense of humor, and he and Astor got along wonderfully.’

Adriana Gibello, Summer Rises, 2015

Adriana Gibello, Foliage Instruments, 2015

Throughout his career, Piazzolla wrote and arranged specifically for the musicians in his group. Contrabajisimo, the new work in the recording and perhaps the highlight of Zero Hour, is dedicated to Console. Piazzolla also constantly reworked his material, as if probing it from different angles. Tanguedia III opens with voices—the members of the group—reciting, mantra-like, the words ‘tango-tragedia-comedia-kilombo (whorehouse)’, Piazzolla’s tongue-in-cheek formula for Nuevo Tango. Up close, you can hear Piazzolla himself kidding around in Italian, breaking up his players. The piece was first recorded in 1984, for the film The Exile of Gardel, but this version has sinister elegance and greater weight. Milonga Loca, actually Tanguedia II and originally part of the same soundtrack, has become faster, looser and crisper here.

Concierto para Quinteto, first recorded in 1971, not only features notable contributions by Suarez Paz and Piazzolla, it offers a glimpse of where Piazzolla was going with the group. ‘Ah, yes, I had to take a test in the rehearsals showing him that I was not playing jazz and I was getting a handle on improvising with the Buenos Aires feel that Ziegler had mastered,’ says Malvicino. ‘After Zero Hour I got carte blanche and improvised much more.’

Adriana Gibello, Everything Happened, 2016

Adriana Gibello, Ancient Boundaries, n.d.

These are demanding pieces, yet the individual playing remains consistently precise and intense throughout. As an ensemble, Piazzolla and his New Tango Quintet sound focused, loose and forceful. They are in total control of the music and prove it by casually changing direction, moods and dynamics on a dime. Piazzolla immediately recognized that the quintet had accomplished something special, believing it to be ‘the greatest record I’ve made in my life. We gave our souls to it. This is the record I can give to my grandchildren and say, This is what we did with our lives.’

After Zero Hour, the quintet would go on to produce one more masterpiece, the underrated La Camorra, a magnificent summation of tango history that stands as Piazzolla’s final tribute to those who came before him and a dare to those who might follow him.

Adriana Gibello, Ancient Boundaries, n.d.

Ariadna Gibello, Ancient Boundaries, n.d.

With so much to choose from, Piazzolla fans will argue endlessly about favorite players, groups, arrangements and performances. But sometime in May 1986, in New York, Astor Piazzolla, Fernando Suárez Paz, Pablo Ziegler, Horacio Malvicino Sr., Hector Console and Kip Hanrahan found their hora cero at exactly the same time.

ASTOR PIAZZOLLA’S ‘TANGO ZERO HOUR’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part One Chapter 11

Tango, tragedia, comedia, kilombo! Opening in a bordello, ‘Tanguedia III’ opens Tango: Zero Hour, Astor Piazzolla’s magnificent new album. Echoing the whorehouse cant, ice cubes crackle as you pour Cinzano into a glass … Through your hair, to the nape of your neck, my mouth weaves its way; there, in that secret glade where Indian summer holds sway, my lips begin to graze. Giggling, you shrink into my arms and caress the back of my hands.

̶ Oh Sprague, this music makes me homesick!

̶ It does? Why?

Pine tar and damp vegetation, cinnamon, cloves and gentian: Your scent signs your signature.

Adriana Gibello, As strangers… themselves, 2016

Adriana Gibello, There… flowers, 2016

̶ I play tango, with a band in Zürich.

̶ Really?

̶ Yes. We play in bars and clubs.

̶ I’d love to hear you!

̶ You will, one day. Cheers!

Upon those words the fragrant chill of the vermouth becomes a thrill; we step into the living room and fall silent on the sofa, listening to the music.

‘Tanguedia III’ is enthralling; its insinuating rhythms stop and go, shifting tempo. At times every instrument in the quintet becomes percussive, until the slow-burning fire bursts into a full-blown conflagration.

̶ Is tango very different from classical music, Marietta? To play, I mean.

̶ Oh yes, and it’s not just a question of technique. It’s more about attitude. The passion, the feel, the rhythmic drive—tango’s got a whole culture behind it, a fierce pride.

Neuchâtel is a world away from Romani ritual: How did you acquire that fierce pride and passion, that fire that branded ‘Tzigane’ in my heart? I’m sure you’re just as convincing in the idiom of Buenos Aires low-life.

̶ You hear that slow, descending line, the minor key? you ask.

̶ Yes.

̶ That’s the milonga pattern. It comes from song. Compare it to the first piece, and you clearly hear the two extremes of tango: very strict, driving rhythm, and extremely romantic music.

̶ That’s a compelling combination!

Adriana Gibello, When you… it, 2016

Adriana Gibello, A Tear of the Sun, 2015

̶ Yes, and it’s not just across pieces, but in every piece! That’s tango, that blending of extremes. So when you play it, you’ve got to think more vertically, in terms of rhythms and chords, and not just horizontally, as melody, like in classical music.

Dark and brooding, ‘Milonga del Angel’ distills its tristeza.

̶ You hear the violin there? Those long, détaché strokes? It’s imitating the bandoneon, its elongated lines.

̶ That’s right!

̶ You hear that emulation in other ways too. For example, when the bandoneon player, after pulling out his arms…

I feel my smile mimicking the gesture you’re miming.

̶ …pushes in to play the first phrase, you get a huge rhythmic pulse towards the first note. Well, on the violin, you use bow speed to get that effect, on the point of the beat.

̶ Interesting, that kind of transposition.

̶ Yes. That’s part of the bag of tricks, to sound like a real tanguera.

FROM LATER IN CHAPTER 11

Here it comes, the old pain, just like I knew it would.

̶ Sprague!

You toss the photos onto the table and leap into my lap. From the ancient well, from the wound that won’t heal, my tears come.

̶ Listen, Sprague, listen to the music!.

You kiss my eyes.

̶ Tango is like the blues.

I don’t want you to see me like this. Certainly not now.

̶ It’s an investigation…

You kiss my cheeks.

̶ …of human relationships…

You lap up my tears with your tongue.

̶ …of what it means to be human…

You wipe my face with your hair.

̶ …in a world that is lonely.

I get a grip on myself, and then I start crying again.

̶ Oh Sprague!

Tamihito Yoshikawa, Incandescent Instant, 2018

Tamihito Yoshikawa, Ginkgo, 2018

Enough! The horror

Of being incomprehensible:

Love me till I’m intelligible

With loving kindness your lips flutter along my face, a butterfly foraging grace from affliction.

Sister of mercy,

See beyond my tears: See into

The wasteland inside me

Pine tar and damp vegetation, cinnamon, cloves and gentian: Your scent is an antidote to my sorrow. Starbright! Like a bee into a peony you slip your tongue into my mouth.

By what miracle

Have you come into my life?

Resuscitation

My fingers ride the silk route of your spine; in the lustrous thicket of your hair they harvest the bombycin fleece.

̶ Listen: You hear how the violin alternates between playing the melody and providing percussive background?

̶ That’s a violin, that plucking?

̶ Yes.

You rise onto your knees: I pull you back down.

Lady, do not rise

Till Lazarus has bestowed

His blessing: A kiss

‘Milonga Loca’ is utterly beguiling.

̶ He’s playing pizzicato with the right hand while touching the side of the string with the second fingernail of his left hand. That’s what creates that metallic sound.

You slip out of my embrace and sit sideways on the sofa.

Tamihito Yoshikawa, Nage au crépuscule, 2018

Tamihito Yoshikawa, Brume sur le lac, 2018

̶ It’s exhausting, playing tango.

I turn to face you.

̶ Every single note has to have life in it, be given its proper weight. Otherwise it falls flat, it’s not tango.

Like rock: Without roll, it’s flat.

̶ You need forceful, driving rhythm together with elegance, always.

From parking your car to pinning up your hair, everything you do is done with elegance.

̶ Of course, Piazzolla’s music is much more sophisticated than ordinary tango. Jazz, classical, contemporary—it’s all in the mix.

̶ Yes. Now let’s dirty it up, Marietta. Let’s take tango back to the bordello!

Ruthless is your beauty as you stare into my eyes; ruthless, without compromise.

̶ All right. Let’s.

SPOTIFY: THREE ASTOR PIAZZOLLA ALBUMS

Astor Piazzolla: The Rough Dancer and the Cyclical Night

Astor Piazzolla: La Camorra

Astor Piazzolla: Tango Zero Hour

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

ASTOR PIAZZOLLA: 57 MINUTOS CON LA REALIDAD

Producer Kip Hanrahan on ‘57 Minutos con la Realidad’

The following text constitutes the first set of liner notes to the 1996 Astor Piazzolla album.

Getting right to an angle that matters: this isn’t Astor Piazzolla’s last record, it’s a sketch of what could have been a last statement/record. Or maybe a set of sketches, forming a blueprint of a last record. There’s a difference, but I’m not sure if the truth doesn’t go back and forth.

Manolo Valdés, Retrato I, 2017

Manolo Valdés, Retrato V, 2018

The record we wanted to make with the Sextet… There were going to be pieces in which the two bandoneon voicings reached false endings using the classic dark harmonies within which Tango (and a younger Astor) heard a comfortable resolve, followed by another, maybe more truthful ending, formed with those chord voicings, dissonances, harmonies within which an older Astor, and those of us who got to travel with him, heard ourselves. In regard to the reintroduction of the two-bandoneon line up in the sextet, Astor never stopped incorporating and being critical of both his own personal history and the tango tradition with which and against which he defined himself. He just got wittier and deeper, and more tender and more critical at the same time. It was never a passive nostalgia. There was going to be a new arrangement of Melancholia de Buenos Aires and of Three Minutes with Reality. Well, we did get Three Minutes with Reality. Hey, check out Gandini there, or on Imagenes, or anywhere. Christ, his work is always stunning. And check out Malvi’s run in Three Minutes. It’s exciting to hear Malvi do that again in this music. Remember the surprising bop-into-nuevo tango runs Malvi supplied to Astor’s Octeto Buenos Aires in the mid-fifties? Remember Octeto Buenos Aires?

Anyway, the record that exists was posthumously finished and assembled as to exact, derailed instructions written by and gone over with El Troesma [Buenos Aires slang for ‘maestro’] a few months before his final stroke. It was at that point we realized that we might not have the time or financial opportunity to record, or according to the book-keepers, re-record the record correctly. Unless we went over all the available material and decided what needed to be changed, assembled, eclipsed, referred to, and unless we constructed a schema, the record company would uncritically assemble the unfinished material and release it, possibly as Astor’s epitaph… Hell, it could never really be anything but comically inconclusive… We used to joke about Prelude to the Cyclical Night being his fake epitaph, Astor’s false ending. It made sense to conclude this disc with it.

Manolo Valdés, Retrato II, 2018

Manolo Valdés, Retrato IV, 2018

The bass parts for both Imagenes and Milonga Para Tres were re-written by Astor and, according to his instructions, overdubbed with Andy Gonzalez in New York. I’m a little puzzled by Astor’s insistent choice of the BBC concert to supplement the studio stuff. It came to me as sonic limitations—we had only a two-track DAT for re-EQing and editing—and a handful of mistakes that I knew Astor would hate, but that I could do nothing about. Astor, however, swore that what he heard was the document of the live Sextet, and he was the one to know. Again, any of Gandini’s and Malvi’s work with Astor shines.

On the other projects I worked on with Astor, I’d finish the record according to his detailed instructions, then finish another record, sometimes a radically alternative record, and send both tapes to the Master. Usually he’d call back immediately, excited, and with a few changes, decide to go with my alternative. Without a shot at Astor’s final approval, I of course was locked into his last instructions, taking only the creative freedom he explicitly gave me for this project. Oh, man, the record we wanted to make… So here, joining his unfinished opera about the discovery of the New World and his unrealized plans to reform the Quintet for one last tour and record, is the sextet record. But at least for this we have a beautiful set of detailed notes.

Manolo Valdés, Naranja y Espejo, 2018

ASTOR PIAZZOLLA: INTERVIEW & CAPSULE BIOGRAPHY

Tony Staveacre

The following text constitutes the second set of liner notes to 57 Minutos con la Realidad, the 1996 Astor Piazzolla album.

Lautaro Cuttica, Dancer Resting, 2018

Have you ever been to a concert that had the effect on you of opening a new door into music? It happened to me in 1989 in Berlin. I’d gone there to meet a legend called Astor Piazzolla. He was booked to play a concert with his New Tango Sextet, in the garden of the Nationalgalerie—Mies van der Rohe’s final architectural flourish in the city which abandoned him in 1933. It was very hot. I’d just got off the plane, no time to change my shirt. I was distinctly underdressed in an audience that sported the fanciest of waistcoats, exotic headgear, expensive footwear. The concert was due to start at six o’clock. The sun was still high in the sky. I found a place to sit, under the elbow of Henry Moore’s Archer. When the garden was full, the standees gathered on the black steel roof of the gallery. More than three thousand tickets sold.

The band made a discreet entrance. Six elderly gentlemen, uniform black shirts, no smiles. They tuned up and started to play—and it was like a rush of cool, salty air through that hot Berlin night. That was my introduction to Tango Nuevo. You couldn’t connect it to anything else in music. Piano, double bass and guitar created a bumpy rhythmic figure, over which the two soloists coaxed a jarring, swooping melody from their serpentine squeeze boxes. There was a sigh of recognition from the audience around me. The musicians were soon drenched with sweat.

Lautaro Cuttica, From Dust to Dust, 2019

Lautaro Cuttica, Ascension, 2019

Traditional tango is overblown passion, gypsy melodies and an Arthur Murray dance step with an inflexible tempo that leans on the fourth beat of the bar. Piazzolla created a new music, full of harmonic and textural innovations, combined with a swinging jazz sensibility. His records created an audience in North America and Europe: the 1989 tour was a sell-out to devotees in both continents. My mission in Berlin was to persuade the musicians to make a detour to Bristol between Berlin and Rome, to record a programme for BBC television.

We met for dinner after the gig, at the Hotel Berlin. Still in black shirts: Binelli, Gandini, Bragato, Malvicino and the bassist Console with his beautiful wife. The leader was amazingly sprightly for a 68-year-old with a serious heart condition who’d just done a work-out in the heat of the sun. He drafted a running order for our programme on the back of the menu. He was anxious to discuss the matter of the boxes. ‘They should be eighteen inches square, exactly. And solid. ‘For the legs, you understand.’ I didn’t. He explained: the left leg of the bandoneon player needs to be raised, so that the extended instrument can rest across it. The bandoneon is an accordion on the grand scale: 78 buttons, using all ten fingers, with a massive three-foot bellows.

Lautaro Cuttica, Swimming Pool, 2018

Lautaro Cuttica, Untitled, 2016

‘The Germans invented the bandoneon’, Piazzolla told me, ‘as a portable organ for churches that couldn’t afford the real thing. But it was an Irish sailor who first brought the instrument to Argentina, in 1890. And then it was played in the whore-houses. The Italian accordion players adapted it for their tango bands, because it has a very sad sound’. A hybrid instrument for a hybrid music. Tango derives from the Cuban habanera, the Andalusian tango, the candombe from Uruguay. All these dances have a syncopated rhythmic pattern in common: tumm te tum tum… ‘It doesn’t have the richness, as Brazilian music has, of the percussion and drums. That’s the difference between Brazil and Argentina. We are introverted where the Brazilians are extroverted. That’s why the tango is always sad; it’s never happy music’.

The early tango was an aggressive, often violent dance, with movements suggestive of knife fights and sexual stimulation: the corte (frozen moment), the quebrada (twist), the refalada (glide). In the 1920s it became a popular song form, and was romanticized. Carlos Gardel emerged from the slums of Buenos Aires to become a tango star in Europe and America. In New York, he was introduced to a 13-year-old bandoneon player who had taught himself to play Bach preludes on this beast of an instrument. This was Piazzolla. He played in Gardel’s orchestra and appeared in films with him. In 1954 he won a scholarship to study composition with Nadia Boulanger in Paris.

Lautaro Cuttica, Untitled, 2016

Lautaro Cuttica, Untitled, 2016

‘I was writing symphonies, chamber music, string quartets. But when Nadia Boulanger analyzed my music, she complained that she couldn’t find any Piazzolla in there. She could find Ravel and Stravinsky, maybe Béla Bartόk, or Hindemith—but never Piazzolla. The truth is, I was ashamed to tell her that I was a tango musician, that I had worked in the whore-houses and cabarets of Buenos Aires. “Tango musician” was a dirty word in Argentina when I was young. It was the underworld. But Nadia made me play a tango song for her on the piano, and then she said, “You idiot, don’t you know? This is the real Piazzolla, not the other one. You can throw all that other music away”. So I threw away ten years’ work and started with my New Tango in 1954’.

In the years that followed, he reached beyond tango’s traditional borders to redefine the form. This caused a furore in Buenos Aires. ‘They said I was out of my mind, they said I was a Martian—anything but a man of tango. A man beat me up in the street outside a cabaret, because he said I was changing the music! I suppose it was a sentimental problem. But traditional tango is boring. It’s repetitive—the same old tunes, the same cheap harmonies. You play it like a robot. I wanted to make a change—it was in my blood. I found a new way of composing, and a new way of playing, a new expression. You must remember: the people of Argentina are emotional.’

Lautaro Cuttica, Untitled, 2016

Lautaro Cuttica, Untitled, 2016

‘They like to cry. They always remember their dead—but my music doesn’t speak the language of the dead. I speak the language of people who are alive, young, and of the future. Young people who like rock & roll also like my music, because it is exciting, aggressive, new and romantic.’

Three days after Berlin, a minibus brought the New Tango Sextet from Heathrow to Bristol. The boxes were inspected and found to be satisfactory. Eyebrows were raised at the exotic bandstand created for the studio by designer Edward Lipscombe. The television director wanted the musicians to play ‘in the round’, facing one another, backs to the audience. This eccentricity was the subject of a lengthy debate in Spanish. But they agreed, and played for an hour, holding audience and studio crew spellbound. When he left, Piazzolla said to me: ‘I think sometimes musicians can achieve what the diplomats never will’.

Lautaro Cuttica, Untitled, 2016

Lautaro Cuttica, The Pilgrimage, 2018

As it turned out, this was one of Piazzolla’s last public performances. In Paris, he suffered a crippling stroke. Argentine president Menem personally arranged for his repatriation to Argentina. But his life in music was over. He died in Buenos Aires on 4 July 1992. He was only seventy-one.

ASTOR PIAZZOLLA: AN AUDIO BIOGRAPHY, A BOOK, A GUARDIAN ARTICLE

Audio Bio: Astor Piazzolla [in French]

Astor Piazzolla: ‘I am a man of tango’

VIDEO: ASTOR PIAZZOLLA, THREE CONCERTS

Astor Piazzolla Quintet: Live in Germany

Astor Piazzolla Live: About the bandoneon | Zero Hour

Astor Piazzolla: Live at the Montreal Jazz Festival, 1984