‘Earth Rising to Heaven’

EMILY BRONTË: EXPERIENCE OF NATURE, PRACTICE OF POETRY

Stevie Davies

Posted by kind permission of Stevie Davies, novelist, essayist and short story writer; fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and the Welsh Academy; Professor of Creative Writing at Swansea University.

From Stevie Davies, Emily Brontë: The Artist as a Free Woman (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1983) 61-76

Emily Brontë, The Old Stoic, Poem 121

Liberty was not only a state of mind to be entered into, but inhered in a local place to be visited. Emily Brontë’s boast of being untouchable by the preoccupations with wealth, love and fame which animate the inferior majority of people was fortified by the accident of place which provided an area literally on Emily’s doorstep, in which she could breathe oxygen that had been through no one else’s lungs, for hardly anyone ever went there, and move freely and haphazardly because there were no rights of way. This place of liberty, upon which she founded her conception of beauty and her idea of value, and which became essential to her continued health, was the moorland behind her home. The poem above, written at the age of nearly 23, admits that she had been aware of impulses to be economically independent; to seek love; to be known. In place of these transient whims has come an undivided and serious aim, to be left alone. She wishes to be an outsider, because going outside was, literally, pure joy.

Looking towards Scar Hill over Haworth Moor | Photo: Simon Warner / Howard Beck

Haworth Parsonage and Church stand on the border of the village whose cobbled main street fell steeply down to the valley, flanked by terraced weavers’ and wool-combers’ cottages of massive local stone, and crowded with 4,000 inhabitants living in great squalor. Outside the front windows, an army of Haworth dead reposed under dark wedges of stone without a blade of grass to be seen. This crazy-paving of gravestones prevented the decomposition of dead bodies from going ahead at a healthy pace, and the arrested putrefaction was fed into the well which some aberrant engineer had sunk into the graveyard and out of which the village drank its water. Typhus was endemic. In the vault of the church itself other corpses lay, exuding the scent of putrefaction into the nostrils of the worshippers. Haworth could claim to be one of the most unhygienic corners of England, full of overflowing cesspits and middens which made it prudent to tread carefully along the road. Infant mortality stood at 41%. Emily as a little girl looked down from the parlour or nursery window upon this prospect.

The churchyard at Haworth where most of the Brontë family are buried | Photo: Simon Warner / Howard Beck

But on the other side of the walls bounding the graveyard, like a great sea of grass and heather, Haworth Moor washed cleanly up against her world. It rose gently beyond the house, dipping and then inclining into the wilder, exposed countryside of Penistone Hill. From here she could walk directly onto adjoining moors, founded on the same sandy, acidic soil formed by the kind of rough stone which is called millstone grit. There is not much that human beings can do with infertile and barren moorland except quarry for rock, and this was done in Emily’s day: the cold flagstones paving the floor of her home, as well as the pavements of the village, the gravestones and the squared stone of which the houses are built, were all hewn out of the moor Or one could dig peat to burn; or simply walk out across the moor seeking solitude.

The heather in full bloom on Haworth Moor | Photo: Simon Warner / Howard Beck

Oddly, except perhaps in Wuthering Heights which is like an extended nature-poem in novel form, Emily Brontë was not primarily a nature-poet. Her lyric gift expressed itself either in personal statements or in dramatization of Gondal conflicts: it is rarely descriptive. Her poetic forms and rhythms are simple and bare, founded on ballad, very tense and stressful. Often, her voice is heard to falter or stammer; the poems may suddenly terminate in mid-thought as unsatisfying fragments; metrical effects may appear gauche or clumsy. Yet in her apparent defects as a poet is rooted the grandeur of her most powerful utterances; hesitant rhythms assume the immediacy of irregular breathing. Rather than providing full-scale descriptions in sensuous terms of the moors she so loved, her poetry is concerned with a philosophy of nature, telling of the relationship between inner and outer worlds. She sometimes shows you the details of the scenery but more often the long vistas of heathland whose large spaces correspond with areas of deep quiet within the introspective self. This loss of identity in an absorbing landscape was something she had felt from her earliest days. She was 20 when she wrote:

Emily Brontë, “I’m happiest when most away”, Poem 37 | Photo (detail): Arnaud Schildknecht, Unsplash

Not to be, or to be bodiless, is here to be ‘happiest’. An idea of what she might mean by the abstraction ‘infinite immensity’ is given by the denial of earth, sea and sky as wholes in favour of spaces bounded by no limit, compared to which earth, sea and sky would appear too detailed and specific. To reach this contemplative ideal in which she could be released into the form of a wandering spirit, Emily had wandered for many miles around the countryside surrounding Haworth, forgetful of self, and conscious only of immense horizons. Clues to the freedom she seeks here had been sensed in the solitude of the high moors.

Photo: Anne Spratt, Unsplash

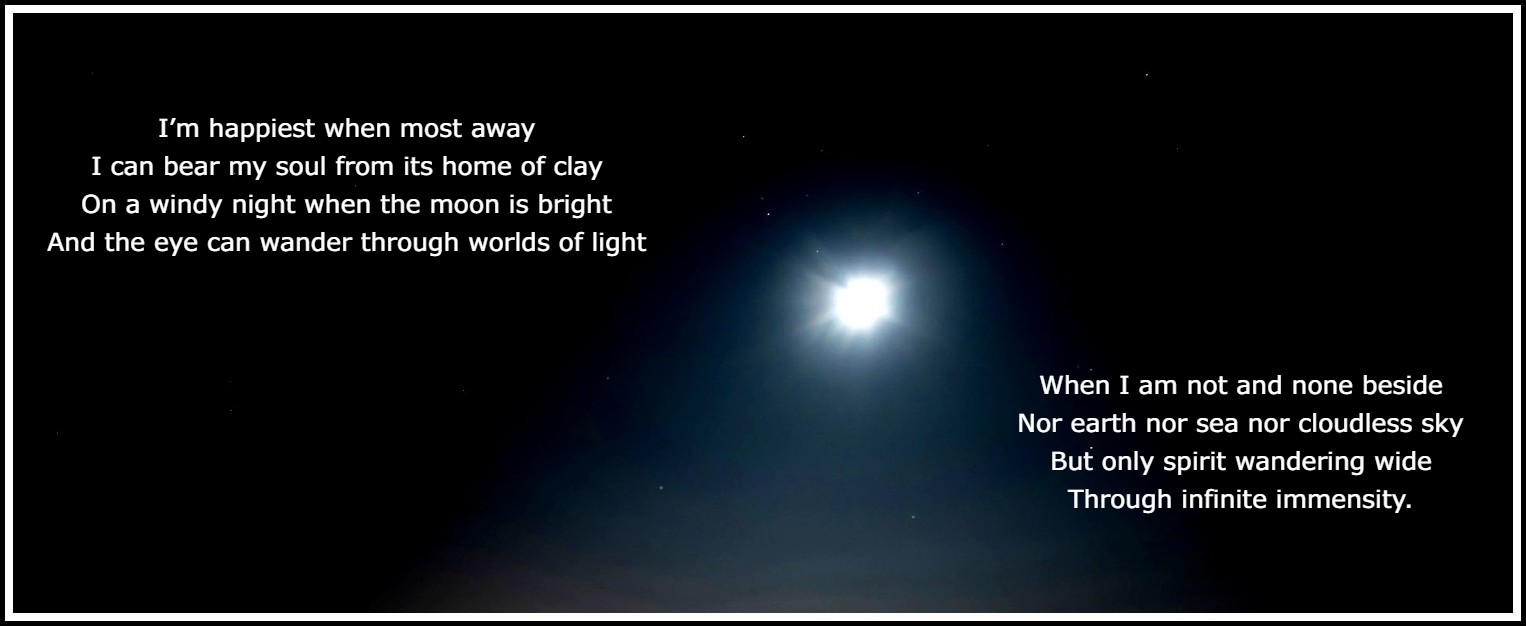

It was not only the large planes and surfaces of the moors which she loved, but also their colour and detail, and the few animals whose habitat is there. The purple heather, calluna, which covers the moors and the bilberry bushes which offer a kind of manna in that wilderness of heath, are often mentioned in Wuthering Heights. These are the principle source of colour. When the bilberries are ripening, they turn from green to red to black: after fruiting prodigally in July and August they turn bright lime-green leaves to a violent crimson, then fall back into the encompassing darkness of the moor in winter. For Emily the moors mean rest, clement on the very verge of annihilation. At the end of Wuthering Heights the graves of Linton, Catherine and Heathcliff are to be crept over in course of time by the grass and heather of the moor. There are no hideous flagstones committing their inmates to the eternally cold mercies of their architecture, but rather the organic absorption of those persons into the peaty moor itself, secure and wholesome. The grass which covers the graves, simple and common as it is, is a manifestation of the natural world which Emily contemplated with love and respect.

The winter sun setting on Haworth Moor | Photo: Simon Warner / Howard Beck

But in the drier ground above Haworth, which Emily associated with safety, freedom and beauty, there is a wealth of grasses—tall tussocks which dry in autumn and winter into beautiful pale golden or whitish masses, and areas of delicate couch-grass whose seeded heads shine in wind and sun; and the strong common grass which in one of the most exquisite imagist fragments in our language Emily makes it possible for us to see in a new light. Below is the whole of the poem as she has left it to us. It justifies its brevity through the initial ‘Only’; this is all we shall be seeing. It may stand for us as a kind of key-poem in assessing her attitudes to language and nature. We remember the laconic Emily who was often thrifty with her language to the point of rudeness. Not only is the subject deliberately commonplace but drastically limited in scope: not a vista of grassland but only ‘some’ blades of conventionally ‘bright green’ grass—a small number of ordinary things offered in wilfully tautologous terms. However, these are not ‘blades’ of grass: they are ‘spires’. Emily’s proudly sacramental view of nature is declared: each grass-blade is shaped like the spire of a church (Catherine would be happy to see the church brought crashing down on her grave in Wuthering Heights). The low plant we tread upon, which can get its root down into any crack, is raised by Emily to the status of something holy. It ‘aspires’ like everything in the world of her imagination. Heaven is brought down to earth and rooted in its sour clays: she will not look into the musty old air of church buildings or the even poorer, darker air of religious dogmas to perceive Heaven.

Emily Brontë – Poem

Her heroine Catherine is very clear that ‘Heaven did not seem to be my home’, for after dreaming that the angels flung her down to earth since she could not accommodate herself to the Afterlife, she wept with joy to find herself on the coherent earth. Below is possibly the last poem she composed. For Emily the earth, as it is, has Paradisal qualities, so that the Christian idea of Heaven becomes an unnecessary fiction and that of Hell a moral irrelevance. She is one of the great iconoclasts of our literature. But these ‘spires’ of bright green grass with which Emily replaces the sterilities of orthodox Christianity are only raised high because the observer is willing to be brought low. If you try to imagine yourself seeing that transparent greenness of the few grasses, you realize that they must be observed close-up, and that you must lie down on the ground to achieve the fullest view. Only this posture makes it possible to look into and through the leaves, charged with the sunlight that discloses their form and colour. The most telling word she retains for the last: it is ‘quivering’. The beauty of what Emily sees on the moors around her home, and which in the deepest sense is her home, derives from the fact that nothing in that world is ever static. She centres her faith not on the mausoleum of the church, enshrining perishable old ideas, but in what moves and is alive now, and in this moment.

Emily Brontë, ‘The earth that wakes one human heart to feeing’, from Stanzas | Photo: Dan Butcher, Unsplash

Emily hates the letter and loves the spirit; is almost physically sickened by forms and formalities, both socially and in religious matters, driving always toward the vital, organic life of ideas. In Emily’s blade of grass the ‘quivering’ motion tells of a vital principle which she can feel on her own skin, intuit from the trembling responsiveness of nature’s most modest productions. It clothes itself in the massive shapes of the hill-sides shouldering up against the sky, their backs turned on human, civic or social concerns. Equally, it clothes itself in the vesture of a tuft of grass, transiently illumined, and of no account in itself. It is found in the fast and icy winds which flow over the moors at all seasons, flattening the aspiring grasses and driving the rare hawthorn trees ‘all one way’ like the gaunt trees at the Heights. It is found in the impulses, passions and fantasies which appear in the mind of the observer of all this excited life, and overflow into a verse which contains and ‘curbs’ the will of the imaginings. The gentle tremor in the grass-leaf belongs to this process of response, self-assertion and the testing out of forms of being against a situation that is elementally open.

Photo: David Xeli, Unsplash

The openness of the countryside around Haworth affects any observer. The moors are open to both sky and wind, the sky being most commonly a moving one, characteristically grey or overcast, with clouds passing away across the horizons. Rock, heather and whin are hammered to such a degree by prevailing winds that it is natural that only tough, fibrous and hardy species survive easily; rocks are weathered out; the country undulates into small troughs and clefts where there is peace from the wind. It is very silent, except for the calling of the birds whose homes are built within the heather: the curlew or the lapwing or peewit, which vault into the air emitting piercing, rhythmic calls. These birds are important symbolic presences in Wuthering Heights. It is said that Emily came to know, through walking around the moors from her tiniest childhood, every clump of heather, outcrop of rock, cleft, gulley and stream. Ellen Nussey, Charlotte’s friend, who came as a rare visitor to the Parsonage, recorded the joy which Emily seemed to feel when she walked out onto the moors, shedding her brooding indoor self, to talk and laugh more freely. Ellen’s account, given late in life, after all the Brontës were dead, in attributing to Emily a suspect ‘gleesome delight’, not to mention a ‘lithesome, graceful figure’ and charming smiles, seems touched with a nostalgic sentimentality consonant with the conventionality of the raconteur.

The Worth Valley from Ponden Kirk | Photo: Simon Warner / Howard Beck

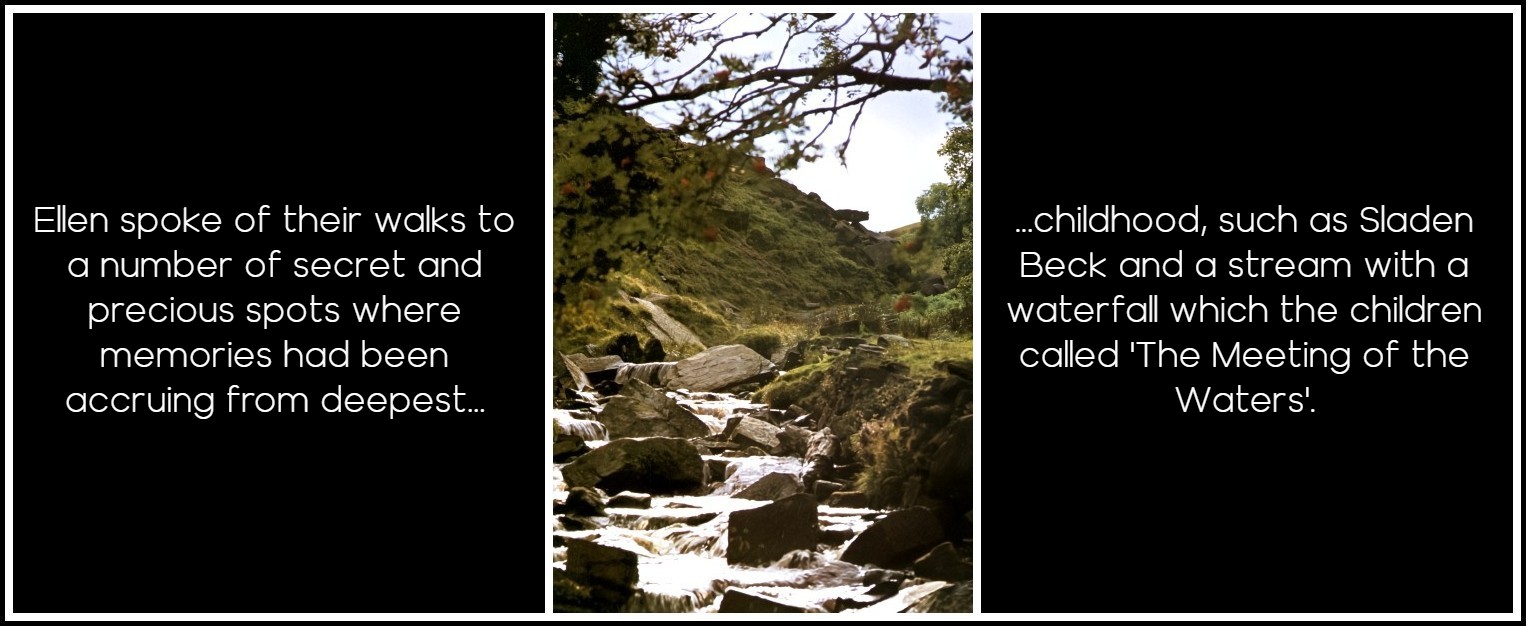

Nevertheless, Ellen has obviously not invented the account of Emily at 15 when she first visited, actually volunteering to take this stranger out for a walk, and opening up into a uniquely communicative mood, impressing the visitor with the geniality and vigour of her mind. Charlotte’s nervous enquiry when they got back as to ‘How did Emily behave?’ has an authentic ring. Ellen also spoke of their walks to a number of secret and precious spots where memories had been accruing from deepest childhood, such as Sladen Beck and a stream with a waterfall which the children called ‘The Meeting of the Waters’: It was a small oasis of emerald green turf, broken here and there by small clear springs: a few large stones serving as resting-places; seated here, we were hidden from all the world, nothing appearing in view but miles and miles of heather, a glorious blue sky, and brightening sun. A fresh breeze wafted on us its exhilarating influence; we laughed and made mirth of each other, and settled we would call ourselves the quartette. Emily, half reclining on a slab of stone, played like a young child with the tadpoles in the water, making them swim about, and then fell to moralizing on the strong and the weak, the brave and the cowardly, as she chased them with her hand. We glimpse here, coming out of hiding, the poet who celebrated ‘All Nature’s million mysteries / The fearful and the fair’. ‘The fair’ is of course easy to love, and is an obvious feature in this refuge of bright green turf surrounding the meeting streams.

Sladen Beck on Haworth Moor | Photo: Simon Warner / Howard Beck

Emily’s joy in the beauty and clemency of the natural world appears as the setting of many of her Gondal poems, in the ‘spell in purple heather’ which acts to bind the observer in a trance, or in the harebell on its ‘slight and stately stem’. She speaks of these as ‘breathing upon’ the human heart, to awaken and warm it into life.

Emily Brontë – from Poem 79

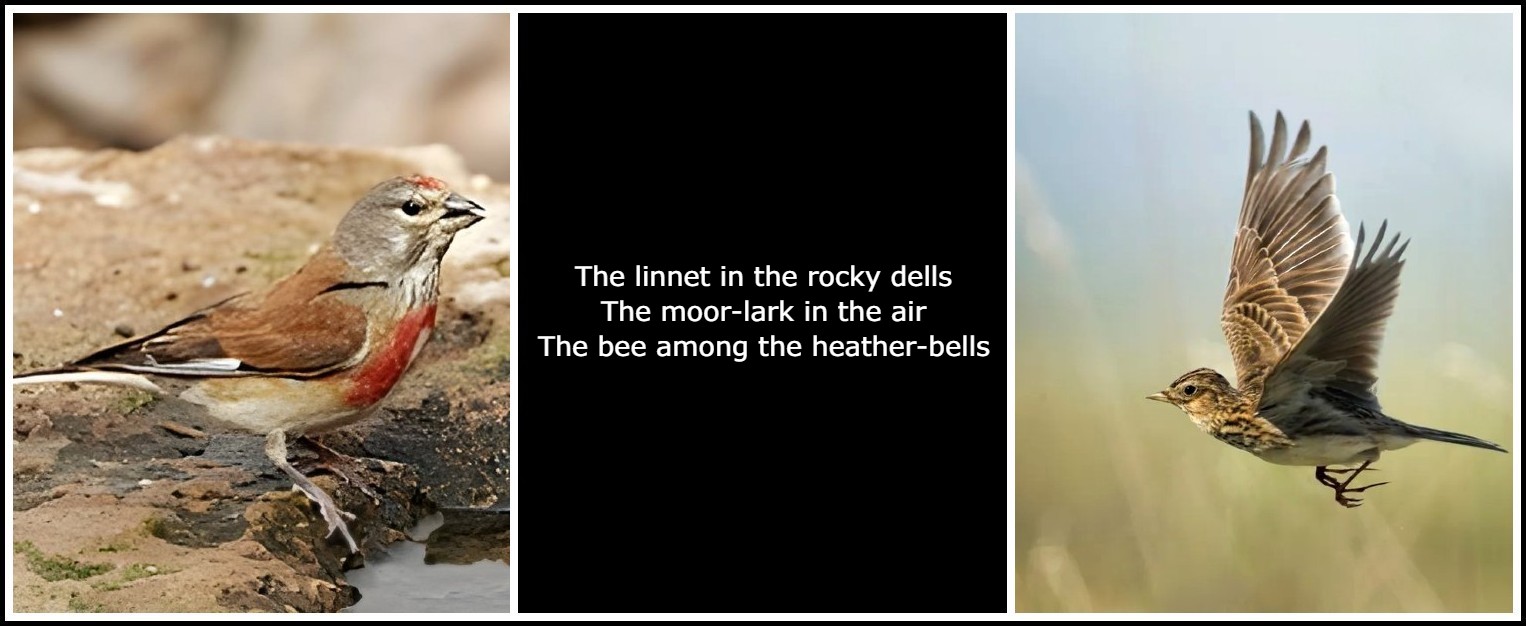

In a later Gondal poem she lists the benign relationships between the animal- and the moorland worlds. These small processes of interaction within nature are felt as too perfect in themselves to need embellishment. Nature is sensed as a pattern of gentle intercommunications between different kinds of individuality.

Emily Brontë – Poem from vi (149), Song

Ellen’s recollection, however, also seems to touch on that other, far less palatable mystery of nature, of which Emily’s poetry did not simply take account but also made its preoccupation, the mystery of ‘the fearful’ aspect of nature, the predatory reality which may underlie any peaceful scene, or that mingling of awe and disturbance with peace in a scrupulous person’s awareness of landscape. Emily is remembered lying out on a stone, dangling her hand in the water like a god from another element, and teasing the underwater creatures, meanwhile discoursing upon ‘the strong and the weak’, disturbing the creatures’ habitat so as to test out their relative powers of adaptation and survival. Ellen says she played ‘like a young child’, but she is also seen studying animal behaviour with an analytic, scientific eye and hand, devising parallels with the behaviour of human animals swimming around in their element. It is very like the deadpan detachment with which she recounted scenes of obscene violence and cruelty in Wuthering Heights: Hareton hanging puppies, Heathcliff ‘grinding down’ his victims. Emily was aware of a power and violence within herself which matched that element of ‘the fearful’ within the natural world, and her lack of inhibition and fear relating to it was raised to the status of a philosophical principle. In one of her French essays written in Brussels, she wrote that ‘life only exists upon a principle of destruction’, so that it is clear that both personal intuitions and observations of natural processes had convinced her very rational mind of a view closely resembling that which would be elucidated as a scientific theory 15 years later by Darwin in The Origin of Species as the law of the survival of the fittest. The weak lose all. The strong inherit the earth. It would have been thought an unforgivably unwomanly point of view, as well as an offensive unchristian heresy.

Emily Brontë – Charles Darwin

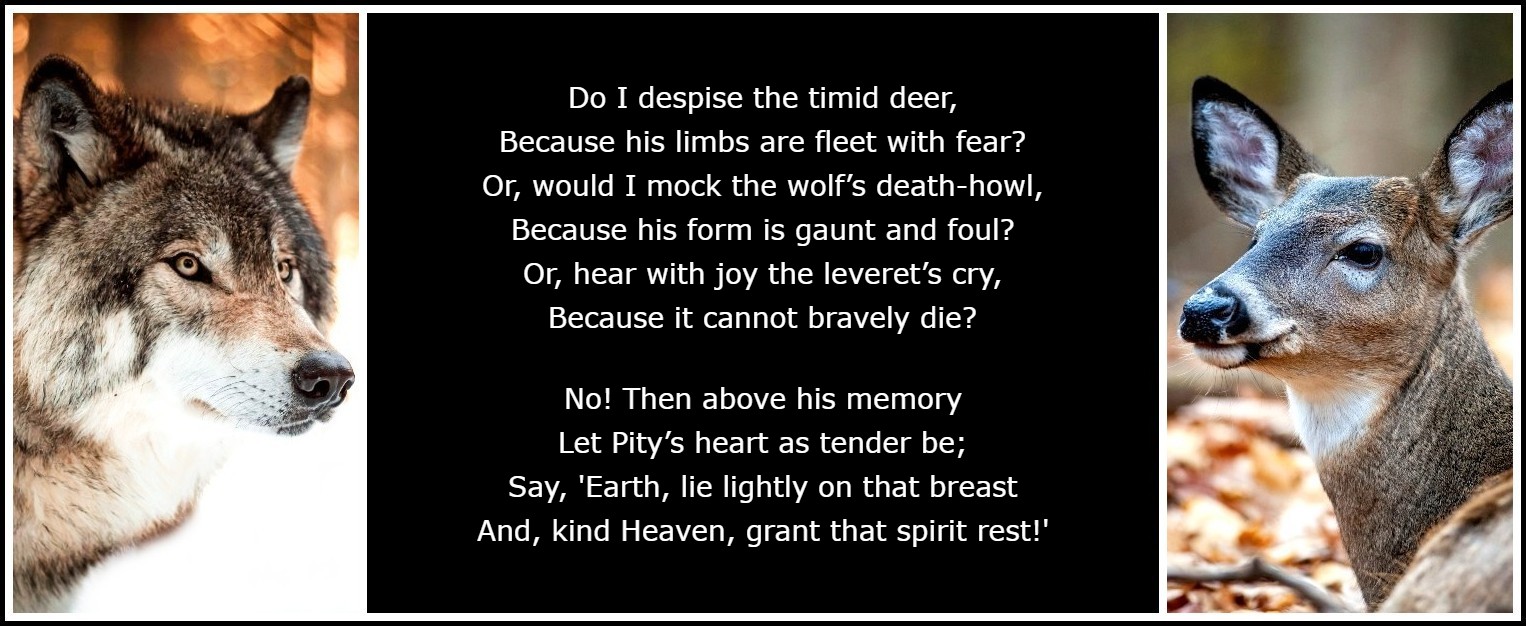

The problem for Emily Brontë lay in deciding who were to be thought of as ‘the fittest’. I think she schooled herself in a compassion that would be based on this natural principle of ‘the strong and the weak’ but which would stretch to embrace both—predator and prey, aggressor and victim—in equal measure. In a Gondal poem of 1839, ‘Well, some may hate’, aged 21, Emily’s persona deliberately revises an instinct to sneer above the grave of a weak and vain person, on the following grounds of the poem presented in the image below. The deer’s timidity is inherited and constitutional, but so is the wolf’s carnivorous appetite. To the final howling of the wolf is added the unbearably high-pitched shriek of the baby-hare, caught in a trap or animal jaws. Compassion is universally and equally apportioned—to the killer and the prey, since both are helpless, at the mercy of inborn responses and inherited conditions. Emily Brontë’s vision of the state of nature here is that of one who sees the subjection of all species to the law of universal carnage, where only the strongest survive, but where the strong are not lovable (the wolf) and their survival is only temporary. Strong and weak in the animal world are subject to the same law, and cannot choose an attitude or stance. Human nature is genetically determined too, so that the dead man, like the young hare, had been born lacking the power to resist his fate or stifle his frailties. Few people have ever had such an absolute conviction of being among the strong as Emily Brontë. But this was only moral strength because it learned to acknowledge the claims of the weak.

Emily Brontë – Poem from xvii (105) Stanzas to— | Photo: Honza Reznik, Unsplash | Photo: Matt Bango, Unsplash

Her poem, like so many others, is in the form of a debate, in which the persona presses the case for compassion and tolerance against something deeply inhumane which lies within himself. I think it represents Emily’s own conflict in coercing herself to abandon or mitigate an instinctive ungentleness toward common frailty, a search for sympathy with those who are voluble in their sufferings, or who cannot make grandiose or epic claims for themselves. Her physical and mental stoicism was so extraordinary that it seems she had constantly to reattune her mind to the evident fact that such qualities must always be rare. In this poem, she records a grudging but successful attempt to concede to the common average. Emily would make several high claims for her superior calibre: ‘Riches I hold in light esteem’, ‘No coward soul is mine’, and these are perhaps her most famous utterances. But her moral greatness as a poet is rooted in her desire to temper her own pride, recognizing kinship with her race rather than claiming exemption. In strenuous contentions between opposing principles within herself, she uses her will to gainsay her will. She is a dualist who systematically forces herself to respect opposites, generating energy from them: in Wuthering Heights, both the raw, wild power such as Heathcliff embodies and the ‘Linton’ qualities of temperance, kindliness and traditional good feeling are acknowledged and polarized. She does not choose the one and abandon the other, but with artistic patience and discipline sustains our sense of the worth of each in its own terms.

Gustave Moreau, Scottish Horseman, 1875

At 18, she had concluded the poem presented in the image below. She had then perceived that being true to one’s own nature, the deepest obligation in her private code of values, depended on being ‘true to all’. Her moral strength lies in her ‘curbing’ and containing of her energies, mocking her own taste for the daemonic and the superhuman, relating her fantasies to the down-to-earth, putting down her own rebellions. The world of nature from which she learned so much about ‘the strong and the weak’ also taught her the necessity of a universal and inclusive compassion. Yet this violence had its own natural opposite within her, coexisting with a wistful, tender lyrical gift, an eye for the vulnerable and delicate, both in nature and in human relationships. Ellen had spoken of seeing Emily and her younger sister constantly ‘twined’ and ‘twinned’ in one another’s arms as they walked out onto the moors. Emily appears in an attitude of loving kindness with one who was her apparent opposite, inseparably together with this tenderly loved, different personality.

Leis Schjelderup, Self Portrait, 1886 | Emily Brontë, ‘True to myself and true to all’, from Poem 170

If Emily loved the moors in their large, dark and wilder manifestations, she also cared for them in detail, for the bright and miniature flowers which belong to the exposed heathland just as familiarly as the coarser scrub, grasses and heathers. In Wuthering Heights, one of the most touching moments is Edgar’s bringing to Catherine in her illness ‘a handful of golden crocuses’ in March, which she identifies as belonging most powerfully to the moors: ‘These are the first flowers at the Heights’. In his final sentence Lockwood notices the harebells amongst the heath and grasses; the second Cathy has teased Hareton by endowing his porridge with a crop of primroses. These small flowers have the status only of fragile moments, evanescent in the expanse of heath and rock which spreads like an eternity full across the vision of Wuthering Heights; but they are included, imbued with their own particular meaning. In the poetry there is a recurrent awareness of the beauty of this kind of detail—tiny bells of ling, a heavy raindrop burdening a spray—details which gain in intensity by being able to assert themselves as individuals in the midst of an undefined wilderness. They contribute to a sense which Emily Brontë as a poet everywhere conveys, that nature is finally consolatory and welcoming to man, even in his mortal moments. Images of extreme cold, inimical to life, carry an extraordinary visual beauty and accuracy, while the tough and fibrous stem and branches of the winter heather, stripped of blossom, are seen as the cradle for a love-child.

Photo: Tom Nickson, Unsplash | Emily Brontë – from Poems 78 & 92 | Photo: Rob Potter, Unsplash

The debate beginning ‘In the earth, the earth’ (presented in the image below), in which two voices argue over whether it is preferable to live or to die, conceives of the mingling of human remains with the underworld mesh of grass-roots as an image of harmony and union. The sombre absence of colour in the first stanza, ‘grey… Black… black’, is implicitly contradicted in the second which manages to yield an impression that the hair which twines with the unseen living roots of grass (as the hair of two people used to be woven together and secured in a locket) will retain its ‘sunny’ character, like buried gold. The grave, in which the corpse is pictured as sandwiched between two layers of ugly ‘black mould’ by the admonitory voice, becomes connected with another kind of living process. Nature is felt, both above and below ground, as man’s original and final home, in which he comes to terms with the mystery of the ‘fearful’.

Emily Brontë, from Poem 139 | Photo: Val Revina, Unsplash

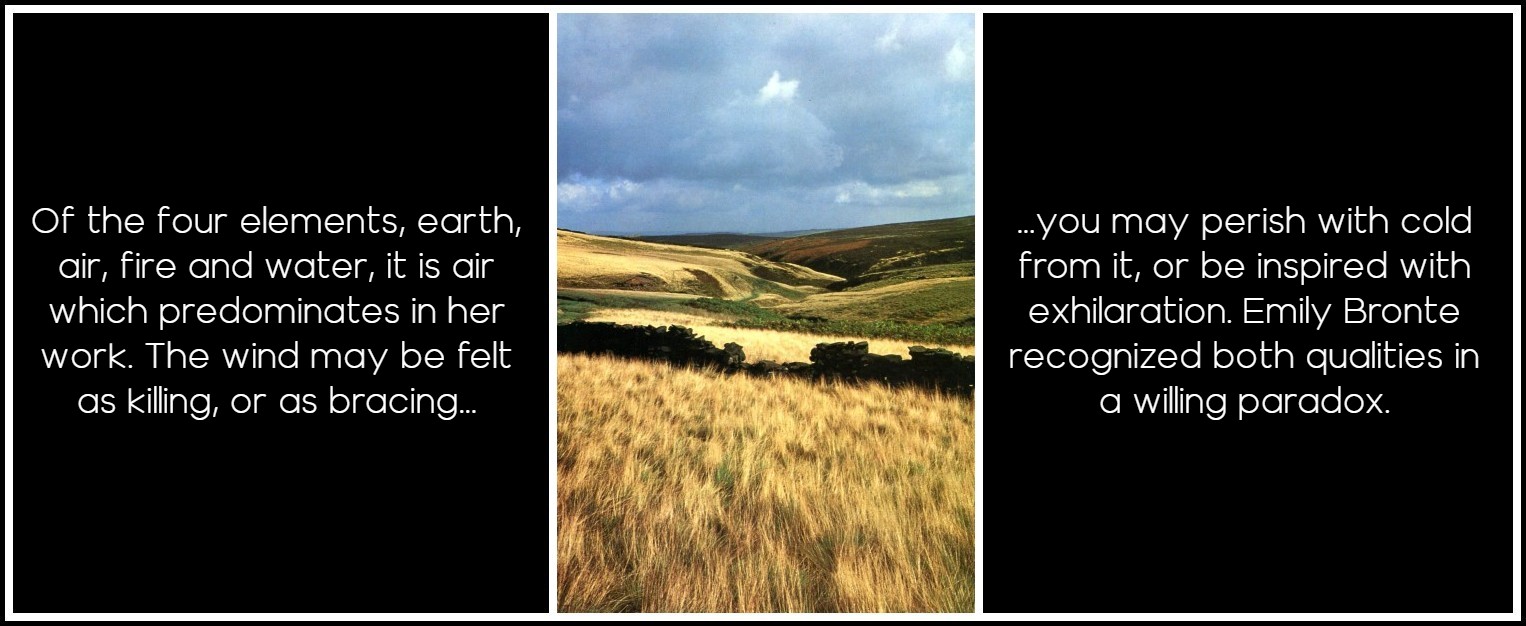

Emily seems to be reaching constantly toward a statement about the natural world which will be satisfying because it is inclusive, bearing the stress of opposites. An image by which she conveyed this union was that of the wind. On the moors above Haworth, at a high altitude above sea level, it is not possible to avoid for long the wind that hammers against the open ridges of heath. Such violent winds are a contributory cause of the formation of heather-moors on the gritstone and limestone high ground of Yorkshire. With recurrent fires, they have prevented the growth of trees in these areas and opened the way on that shallow, peaty, acid soil for heath to develop, so that above the arable meadowland of the valleys (characterized as the ‘Thrushcross’ element in Wuthering Heights), the countryside has become as it is as a direct result of its lack of protection from high winds which make it hostile to other forms of vegetation. Literally, the wind is the breath of life to the moorlands to which Emily devoted herself. Of the four elements, earth, air, fire and water, it is air which predominates in her work. The wind may be felt as killing, or as bracing; you may perish with cold from it, or be inspired with exhilaration. Emily Brontë recognized both qualities in a willing paradox. For her, the wind was symbolic of the creative imagination, powerfully and invisibly driving its transforming force through the objects of contemplation.

Looking east across a windswept Haworth Moor | Photo: Simon Warner / Howard Beck

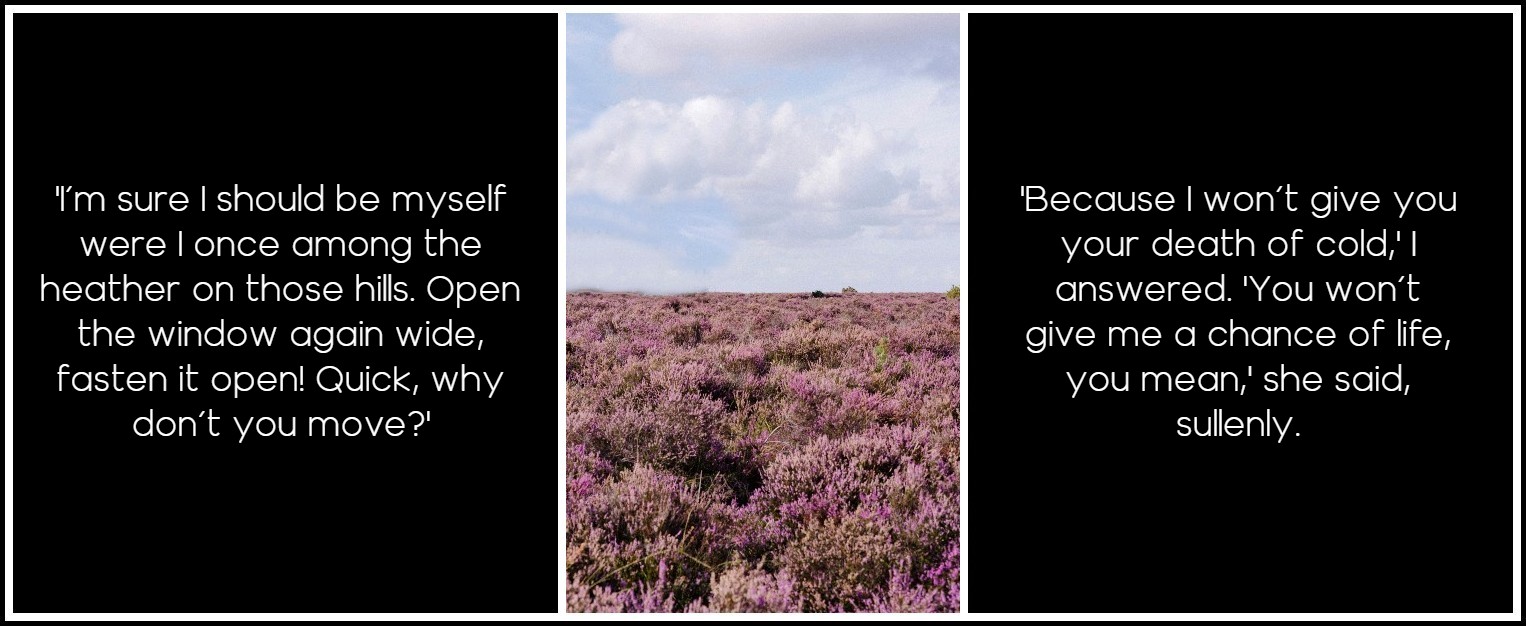

She admired and felt that some principle within her echoed the racing of the wind across the surface of the earth. It was like the careering of Eternity into time which was the pivot of her visionary experiences. The root of the word ‘wind’ in Hebrew has the same meaning as our word ‘spirit’, and this fruitful pun which is traditional in Christian tradition, is a coincidence on which Emily Brontë drew. ‘The wind bloweth where it listeth’ is rendered in some Biblical translations as ‘The spirit bloweth where it listeth’. The wind is liberty; and to stand in it is to be free. It is also the unifier and reconciler in Emily’s vision, like Wordsworth’s idea of a spirit which ‘rolls through all things’ in Tintern Abbey. But because Emily Brontë was always thinking not of an abstract ‘spirit’ but of a wind localized in Yorkshire, a real blustering force which you have to resist in order to maintain your own stance, her conception of this old idea has a powerful originality. The high winds around Penistone Hill and Withens (the supposed original for Wuthering Heights) are relaxing because the necessity for keeping upright entails forgetting to be conscious. They disperse consciousness; cleanse and renew. These are the feelings and experiences Emily is drawing on when she has Catherine, dying from the suffocation her nature feels in the enclosure of Thrushcross Grange, battle to get the window open, so that she can take some of this vital air into her lungs.

Photo: Annie Spratt, Unsplash

Ellen is right to say that the freezing blast will kill Catherine, physically; Catherine right to insist that to drink that air will heal her, spiritually. The tragedy lies in the fact that the two modes of life are shown as not consonant. To achieve the life of one, you must lose the other. To ‘be oneself’ is the most invincible problem raised by the novel. To ‘be herself’ Catherine knows that she must go back; go home. Emily’s novel reveals the fatality involved in growing up, being consigned to time. Nothing can be unwoven, for the web of destiny has been spun, measured out and will be cut. Catherine yearns, ‘I wish I were a girl again, half savage and hardy, and free’, for this is the only way one could get back. She feels that the wind, coming in from her home on the moors, is somehow the clue to getting back across the abyss. It is, but only through the process Ellen so sensibly counsels against, by killing her. In Emily Brontë’s novel, the grief is that though we contain and in essence still are the child in whose form we set out, this is a solely interior condition, revealed in dreams which ‘kill… with desire’. Though it may be theoretically possible to recreate childhood, this can only be subconsciously or through the quickened memory, for there is no permit available from adult life back to the Eden of childhood. Adult life is shown by Emily Brontë as a condition of forfeit and exile—exile even from ‘being oneself’.

Ilya Repin, Dragonfly (Vera Repina), 1884 | Agda Holst, Self-Portrait, 1925

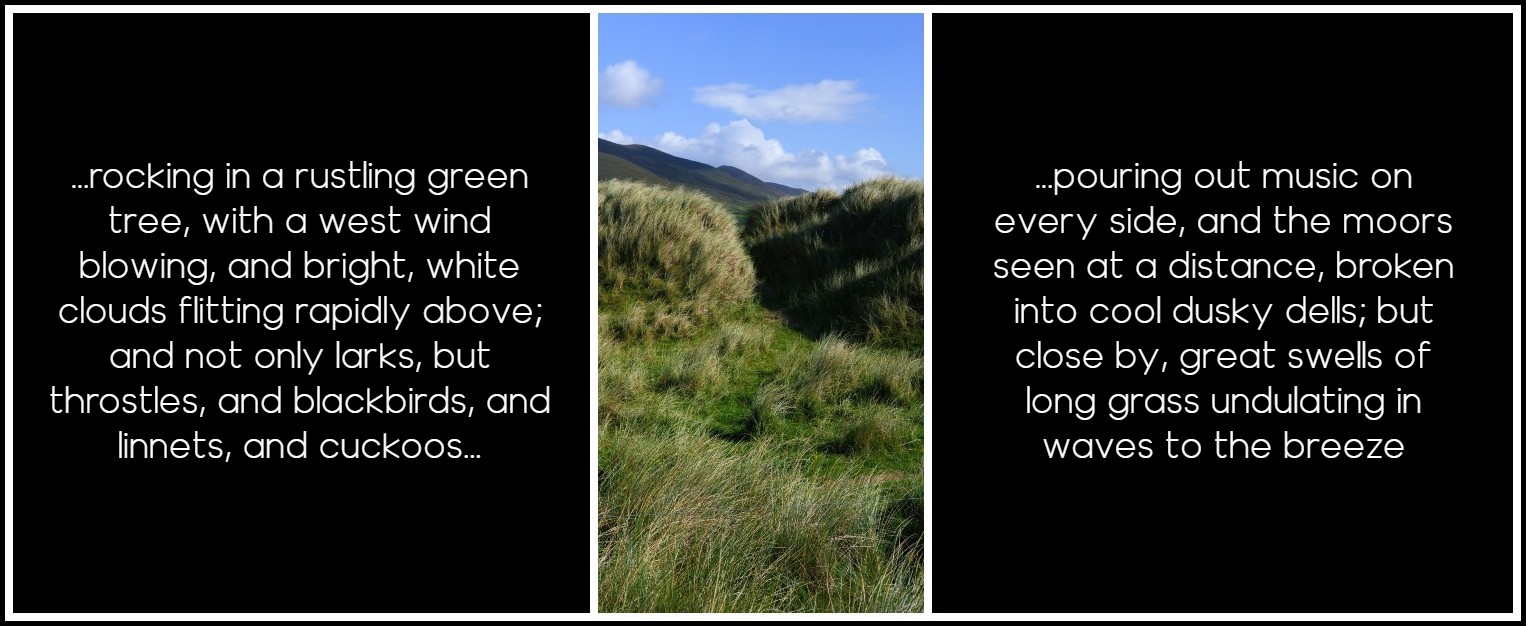

Catherine cannot rejoin Heathcliff in the old way of life: she is married, pregnant, ill and mortal. Heathcliff cannot undo his separation from Catherine in her life-time, for the same reason, and after her life-time because that requires that he survive ‘with (his) soul in the grave’, and, obviously, ‘I cannot live without my life! I cannot live without my soul!’ But there is a suggestion that there does exist a path home on two levels: through that chill, inhuman wind turning one’s life to air, returning one’s body to the mould; through giving birth to a new identity. Catherine is displaced to the younger Cathy. A new child goes out into the world; makes for the Heights instinctively, where the wind’s source is. When Cathy grows up in her turn, she expresses her dream of Paradise presented in the image below. The west wind associated with the return of spring, and with the extravagant symphony of birdsong (song itself is air), co-exists in this poetic speech with one of the most accurately observed and naturalistic images anywhere in Emily’s works, the sea of grass blown upon by the wind. For Cathy as for the author, Paradise is a condition of resolute wakefulness; nothing is quiescent or acquiescent. The wind has turned the acres of meadowgrass to a billowing sea, ‘swells… undulating’, as the invisible force which animates all existence miraculously reveals its presence through its effect upon the visible, pressing down and releasing the grasslands in a rhythmic succession of waves of energy. A violent force expresses itself in effects which are soft to the eye—absolute power; absolute gentleness. This commonplace sight on the hillsides around Haworth is looked at with a fresh, transforming vision.

Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights | Photo: Mary Skrynnikova, Unsplash

Ten years before she wrote Wuthering Heights, at the age of 18, Emily wrote for the first time on this subject of the spirit-wind, in a precocious bravura-piece. Her poem releases tidal waves of images, in which the wind turns the land to a sea; the normal oppositions and incoherencies between things are beaten down. Contrarieties fuse and flow together.

Emily Brontë, ‘High waving heather’, Poem 5

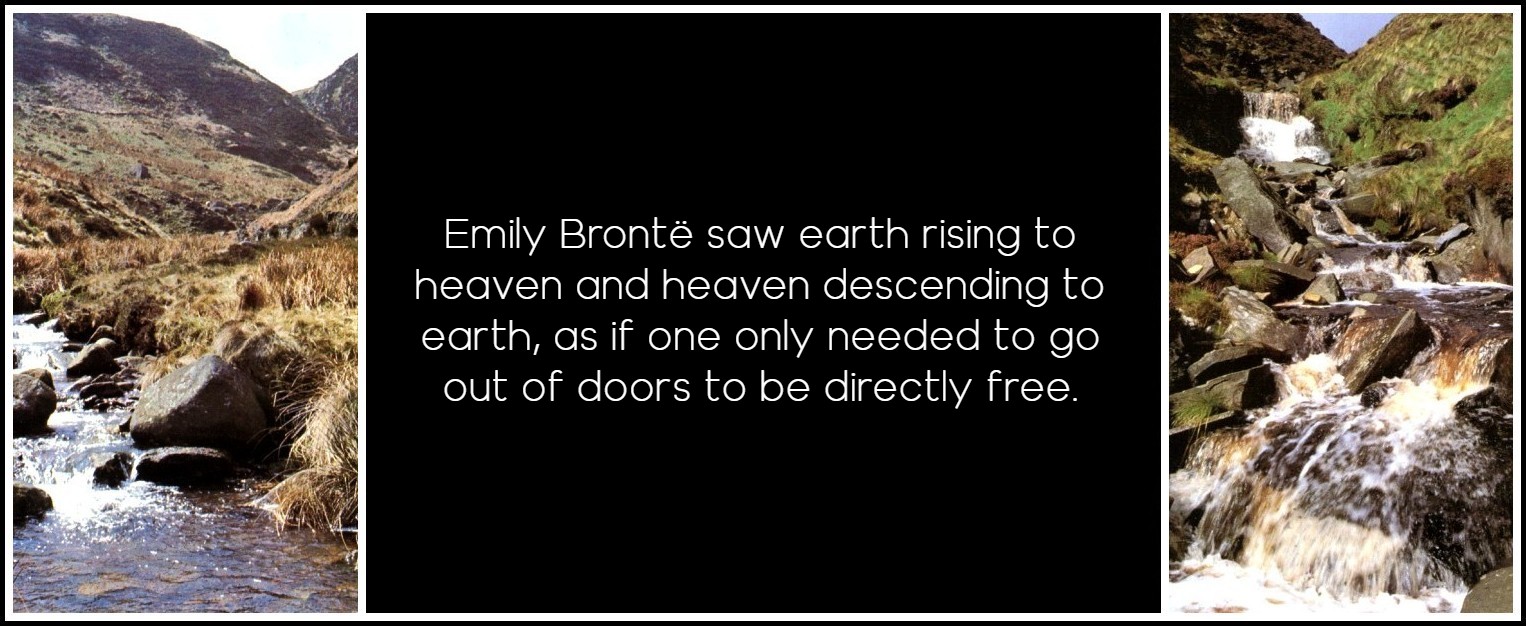

Emily celebrates liberty as change. The energy of the wind abolishes distinctions in the natural world, so that earth meets heaven, water overpowers earth, time accelerates, the shadows of clouds pour over the earth as if in a speeded-up film. Her poem’s rhythms stream over the hypnotically repeated feminine rhyme in a virtuoso outpouring. Each time the present participle sounds, it enacts the moment of release, the ecstatic breaking loose of spirit from body like the tumultuous upheaval of a storm. For Emily, even at this comparatively early age as a poet, the active spiritual principle is seen as imprisoned in the static physical one. The source of the joy which moves the poem is that the wind can ‘burst the fetters and break the bars’ of the heavy clay into which human consciousness is perpetually sinking. There is an assurance that some principle within the natural world is there to breathe upon and recreate the torpid human clay, making undulations in the visible world (like those which Cathy sees in her mind’s eye as waves in fields of long grass) whose rise and fall ‘Shining and lowering and swelling and dying’, makes darkness tolerable and ‘dying’—of sound, of life—welcome, if it is a movement toward something else. The wind whips each creation into an impulsive statement of its own nature, so that it can be itself. Flattening the heather it also lets it go, to stand up for itself in a sea of motion and tumult as ‘High waving heather’. She captures too those days of mingled sun and wind in which clouds chased by high winds cast rapidly moving areas of cold shadow which may be seen approaching from a distance across what comes to seem more a lightscape than a landscape. In this life-long excitement, Emily Brontë saw earth rising to heaven and heaven descending to earth, as if one only needed to go out of doors to be directly free.

The River Worth near Ponden Kirk | A swollen moorland stream at Ponden Kirk | Photos: Simon Warner / Howard Beck

STEVIE DAVIES – THREE NOVELS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments