Life into Literature

JEAN RHYS – VOYAGE IN THE DARK – INTRODUCTION 1

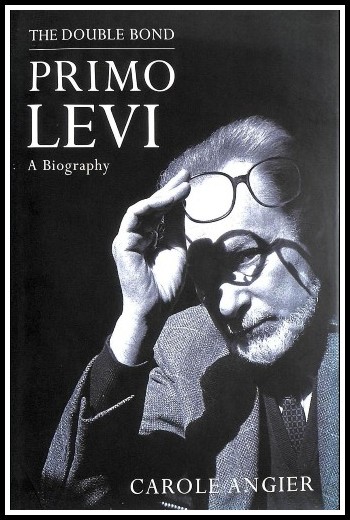

Carole Angier

Posted by kind permission of Carole Angier, eminent biographer of Jean Rhys, Primo Levi and W. G. Sebald; fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

From Carole Angier, Jean Rhys (Penguin Books, ‘Lives of Modern Women’, 1985) pages 31-42, 56-58

Modigliani, Portrait of a Woman, 1918 | Jean Rhys

‘Of course you’ve always known, always remembered, and then you forget so utterly, except that you’ve always known it.’ This is what Anna thinks in Voyage in the Dark, when at last she lies beside her first lover. That was what she had wanted: warmth, his arms around her, words of love. When Anna first met Walter she hadn’t liked him; when he sniffed at the wine and sent it back she even hated him. When she pushed him away he said, ‘I’m very sorry. That was extremely stupid of me,’ and looked at her as though she wasn’t there. But then he sent her a bunch of violets that smelt like rain, and twenty-five pounds. ‘I’m worried about you,’ he wrote. ‘Will you buy yourself some stockings with this? And don’t look anxious while you are buying them, please.’ Then when she was ill he brought her an eiderdown and wine and grapes and soup, and sent his doctor to her. Her room grew bigger; and when his hand touched her face she couldn’t remember that once she hadn’t even liked him. When he put money into her handbag she should have said, ‘Don’t do that,’ but instead she said, ‘Anything you like, any way you like.’ She lay in his bed and thought of the slave list she had seen once, at home: ‘Maillotte Boyd, aged 18. Maillotte Boyd, aged 18… But I like it like this. I don’t want it any other way but this.’ It was the best way to live, because anything might happen. ‘Dressing to go and meet him and coming out of the restaurant and when he kissed you in the taxi going there.’ ‘You’re a perfect darling, but you’re only a baby,’ he said. ‘Let’s go upstairs, let’s go upstairs. You really shock me sometimes, Miss Morgan.’

Ernst Kirchner, Couple in a Room, 1912

That was her life for a year and a half. Walter wanted her to get on: he paid for her to have singing lessons, he introduced her to people. But she didn’t want to get on: she wanted to be with him. ‘Oh, you’ll soon get sick of me,’ he said. ‘Don’t be like a stone that I try to roll up a hill and that always rolls down again.’ So stupid to love someone very much, she thought. So stupid to be afraid of a thought. Well, she wouldn’t think it. And she wouldn’t read books, because books all say it: the man’s bound to get tired. Her lover introduced her to his cousin. He too wanted her to get on (but did that mean move on?). ‘You don’t mean to say you don’t like Vincent?’ Walter said. ‘You’re the only girl I’ve heard of who doesn’t.’ It was true he was handsome, more handsome than Walter, and taller and younger too. But she hated the way they looked at each other when they talked about Vincent’s girl. ‘It’ll end in a flood of tears,’ Vincent would say. ‘As usual.’ Something about him made her say stupid things. ‘Good night, Vincent. Thank you very much.’ Then he would raise his eyebrows. ‘Thank me very much? My dear child, why thank me very much?’

Degas, Singer with Glove, 1878

And in the end she didn’t thank him—she had been right about him, after all. It was he who sent her the letter. ‘I’m quite sure you are a nice girl and that you will be understanding about this. Walter is still very fond of you but he doesn’t love you like that any more, and after all you must always have known that the thing could not go on for ever. He will always be your friend and he wants to arrange that you should be provided for and not have to worry about money (for a time at any rate).’ It had happened. She had known all her life that it would happen. She had been afraid for a long time, but now her fear had grown gigantic. She tried to tell Walter: ‘You think I want more than I do. I only want to see you sometimes, but if I never see you again I’ll die.’ But she saw that he hated her for insisting on this scene, and that his caution and distance had grown gigantic too. So she let go: she fell back into the water and drowned. The dream had ended, and she didn’t care any more. She would never care again. She ran away from the flat without telling him where she had gone. This affair was Ella Gray’s [Jean Rhys’s] first grab at her dream, her first gamble on getting what she wanted out of life. It was also her first and greatest loss.

Sølve Sundsbø, ‘The Girl from Atlantis’, Vogue Nippon (May 2010)

Ella’s real first lover was very like Walter in Voyage in the Dark. He was a stockbroker; he was forty to Ella’s twenty; he had a house off Berkeley Square, and a handsome young cousin. But Walter was just a rather rich, rather ordinary businessman. Ella’s real lover was very rich, and very upper class. When Jean Rhys wrote their story she played down her lover’s wealth and position, partly in order to reduce the element of romantic dream in her novel. In real life, or in her real dream, it was very much there. Ella’s real lover was Lancelot Hugh Smith. He came from a large and distinguished family of bankers, MPs and diplomats. He was more than respectable. He did not pick up Ella as Walter had picked up Anna, on a street: he met her at a supper party. He was Eton and Cambridge; he wore wonderfully cut English clothes, and smelt of leather and smoke; he looked and sounded a completely conventional, rather philistine, entirely solid and secure member of the English establishment. He was not handsome, but to Ella he looked ‘just right—always’. She loved his swinging walk, his gallant, teasing way of talking, which hid (but not from her) how much he felt. He used a secret language too, a male language of upper-class cliché – ‘Kitten, your eyes are shining like stars, by Jove!’. He was kind, he was elegant, he made her laugh; he bought her lovely clothes, and listened to her talk of home. He made her feel less shy. He was father, friend and lover in one—he was perfection, and she thought him a god. It seemed as if, in this first affair, she had gone straight to the heart of her dream.

Tamara de Lempicka, Idyll, 1931

She had—and yet she hadn’t. Lancelot Hugh Smith looked as though he owned the world, and could make it safe for her. But underneath his beautiful clothes and upper-class manner he hid a disposition not so different from her own. He was hyper-sensitive, fastidious and nervous, and had been so all his life. He was too diffident to be successful with women. He never married: he became friend, patron, uncle, godfather, but never husband or father. He liked and admired genuinely confident young men, like his cousin Julian Martin Smith, the model for Vincent. He was—in this business of liaisons—less worldly and less decisive than Julian; he depended on him. Julian was the popular one, the charmer and the womanizer. In fact, it was Julian who was the model Edwardian all the way through: handsome, brave, courteous and unimaginative; an officer and a gentleman. But Ella Gray hated him. She hated him because she thought he had urged Lancelot to leave her; but she also just hated him—for his effortless success, his easy, unquestioning belonging.

Tamara de Lempicka, M. Thadeus Lempicki, 1928

And so her dream had to end. Not because chorus girls couldn’t marry rich respectable men—they did; but because it was a contradictory, impossible dream. She longed for someone entirely secure, yet entirely sensitive; someone utterly respectable and safe, yet able to understand her lonely, fearful, rebellious nature. Against all expectation, Lancelot really was this dream. But being so made him less, not more, able to love her and stay with her. His respectability rejected her, as she’d been afraid it would—and so did the very things that drew him to her, his own hidden loneliness and fear. Lancelot couldn’t bear to see people in pain or need; he didn’t even want to think about them (‘My dear, don’t harrow me. I don’t want to hear’). As soon as he felt the real depths of Ella’s need, he must have wanted to bolt. He lived by—and achieved—the Edwardian ideals of ambition and success. (‘You want to get on, don’t you?’ Walter says to Anna in Voyage in the Dark. ‘But my dear, how do you mean you don’t know? Good God, you must know.’) But underneath he was never sure he wanted or enjoyed them. Ella Gray knew this: ‘Always the battle was going on in him between what he had been taught and what he felt.’ But in Voyage in the Dark she smoothed it over; she made Walter merely safe, solid and philistine, because she wanted to show how the respectable world preserves itself. She was not yet ready to ask herself if the trouble lay less in him than in her dream of him. She was not yet ready to think that even English gentlemen with quiet voices and an easy way of walking might feel unsafe, and suffer.

John Singer Sargent, Léon Delafosse, 1891

When Ella Gray’s affair with Lancelot ended, she wrote a poem: ‘I didn’t know / I didn’t know / I didn’t know’. She didn’t know it was possible to suffer so much—to feel so black and desperate, and then so empty and unreal. For the rest of her life she felt as though some central spring of will and energy inside her had been broken: a terrible feeling of lassitude, as though she had opened her veins in a hot bath. She had only come to life when she was twenty—and by the time she was twenty-two, her life was over.

Modigliani, Jeanne Hébuterne, 1919

Voyage in the Dark tells what happened then. Anna met Ethel, who was a masseuse; she went to work for her as (Ethel said) a manicurist. Ethel always talked about how respectable she was, a lady: ‘A lady—some words have a long thin neck that you’d like to strangle.’ On the surface everything was all right, but underneath Anna glimpsed all sorts of horrors. Then Carl came. He wasn’t like her clients, nervous and hesitating: he was solid, and when he touched her she knew he was quite sure of her. So she thought, ‘All right, then, I will.’ She imagined him taking her away—but then she imagined him talking about her: ‘I picked up a girl in London.’ Not ‘girl’ perhaps. Some other word, perhaps. Never mind. After Carl left there were others. ‘Going up the stairs it was pretty bad but when we got into the bedroom and had drinks it was better.’ And then she was not just tired all the time but sick, and the worst of all happened. ‘Of course as soon as a thing has happened it isn’t fantastic any more, it’s inevitable. The inevitable is what you’re doing or have done. The fantastic is simply what you didn’t do. That goes for everybody.’

Otto Mueller, Couple at Table, 1925

Anna writes to her lover and asks for money for an abortion; instead, his cousin comes, looking fresh and clean and kind. In fact, Lancelot had found her himself; but before long he was ill, and it was Julian who came. Lancelot sent her a big rose plant in a pot, and a beautiful Persian kitten. But it was Julian who sent her the money, in a little canvas bag; and Julian who asked her for Lancelot’s letters back, as Vincent asks for Walter’s: ‘Are you sure these are all?’. He pretended to laugh. ‘Well, there you are. I’m trusting you.’ At the end of Voyage in the Dark Anna hears the doctor say, ‘Ready to start all over again in no time, no doubt.’ Julian’s doctor said much the same thing to Ella. The original ending of Voyage in the Dark suggested that Anna died aborting her child. Jean Rhys’s publisher said that that was too gloomy, and with great reluctance she added the last four lines of the book, to let Anna live. But she felt that she herself had died then, with the end of her first affair—’the real death,’ as she would write in Wide Sargasso Sea, ‘not the one people know about’. It would have been better, then, if she had died outwardly—physically—too. This idea sank deep into her work: that it is better to die than to go on in a living death, ‘To die and be forgotten and at peace. Not to know that one is abandoned, lied about, helpless.’ But she always went on.

Photo (roses): Nikita Muzheskyi, Unsplash | Composite: RJ

Lancelot made her go on, now. He insisted on sending her an allowance, every week, through his solicitors. The impersonality of this felt to her worse than death. For the next six or seven years she took his money, spent it, asked for more; and all the time she hated it—and herself—and him. Once or twice she wrote to him and asked him not to send any more, because it made her so unhappy and stopped her from changing her life. But it made him even more unhappy not to send it, and in the end she always accepted it again. Besides, what could she do? She felt more and more alone, more and more useless. Her habit of reluctant, self-hating dependence had begun. The first months of her death-in-life were among her worst ever, and the feelings she had then were ones she wrote about for the rest of her life. At first she found some work as a film extra; but when she had to sit for hours in a cotton dress in the dead of winter, she ran away again. After that she did nothing at all. She slept as though she were dead for as many hours as possible; the rest of the time she sat staring in front of her, or walking the grey streets like someone in a dream. She didn’t care how she looked. When a man talked to her in a restaurant she saw his lips move, but didn’t hear a word he said. She was frightened of how she felt—so tired, so afraid of people, thinking all the time: ‘Nothing matters, nothing matters.’ Then it was Christmas.

Photo: Getty Images for Unsplash

But suddenly someone knocked on her door—a girl she had met on her first film. Ella saw her looking at the bottle of gin on the table; she laughed loudly and admitted what she had meant to do. ‘But my dear,’ said the girl, ‘this isn’t the right house. It isn’t high enough.’ They had several gins together, and soon Ella was giggling and promising to move to Chelsea, where it wasn’t so gloomy. She had broken her first appointment with death. But underneath now she was set in what she wanted, and in what she believed was true. At the beginning of 1914 she was in the room her friend had found for her, in an area on the edge of Chelsea called (she noticed) World’s End. It was a depressing room, with an ugly, bare table. She saw some quill pens in a stationer’s shop—red, blue, green and yellow: she bought them, to cheer up that damned table. When she noticed some exercise books she bought them too. After her supper of bread and cheese and a glass of milk, she suddenly felt her fingers and the palms of her hands begin to tingle, and she knew what she was going to do. She was going to write down everything that had happened: everything he’d said, everything she’d felt. She opened an exercise book and wrote, ‘This is my diary.’ For a week or ten days she wrote all day and far into the night, pacing her room, laughing and crying. Then it was finished, and the worst blackness lifted. She put the exercise books at the bottom of her suitcase and moved back to Bloomsbury. She knew now that when things got too bad, there was one thing she could do: write it all down. Then she could (almost) forget.

Photo: Sergey Sokolov, Unsplash

For the next eight or nine years, until she began writing stories and novels, she wrote in her diary whenever she was sad or excited, angry or hopeful. Later on she wrote Voyage in the Dark out of its first part. But she let the terrible years after the end of her affair, when she was young and alone in London, remain dark and forgotten. She hardly touched them in her fiction (only in Till September Petronella, set in the summer of 1914); she rarely spoke of them to anyone. But they taught her one of the dark, intensely experienced ideas that dominate her work: that life is a matter of animals fighting for survival, and if you let morality mean anything to you, you are trampled to death before you’ve begun.

Photo: Getty Images for Unsplash

Somehow, she survived. She made a little money sitting for artists; she went back briefly to the stage. But she mostly lived on Lancelot’s allowance. During the war she worked for three days a week as a volunteer in a soldiers’ canteen, serving the men bacon and eggs, coffee and sandwiches, before they left for France. The older ones were thoughtful and, silent, she noticed; but the younger ones often looked excited. ‘Close-up of human nature—isn’t it worth something? In the middle of 1917 her canteen closed. She was living in a cheap boarding house in Torrington Square, and there one afternoon she saw a new arrival. He was a slim man, with quick dark eyes; his name was Jean Lenglet. He was very different from Lancelot—not English, and not stiff and cautious either. He was much more like Ella herself: reckless and fun-loving, a middle-class rebel whose more reasoned dissent from ‘respectable’ society would help her to put her own feelings into words. He was half-French and half-Dutch; he was generous and romantic, direct and natural. Ella didn’t fall in love with him but she liked him, and was impressed by him. She felt he liked women, and understood them; she felt he was contained and sure, and could take her away. When after only a few weeks he asked her to marry him, she accepted without hesitation.

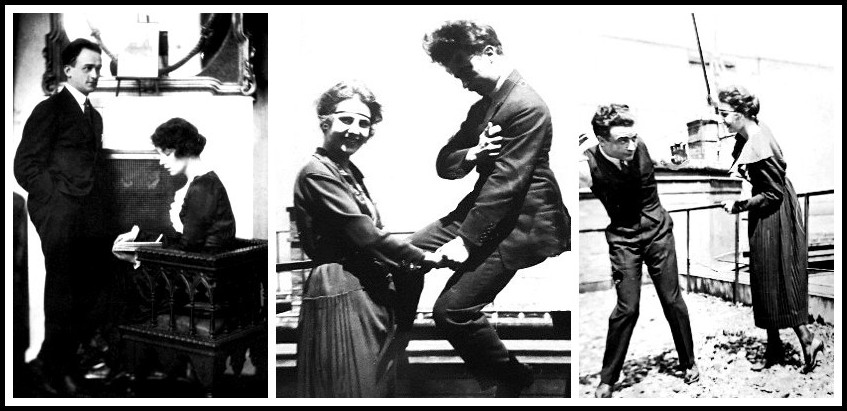

Jean Rhys & Jean Lenglet, Vienna 1921 – The Hague, 1920 | Photos: McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa

She had to wait out 1918 before she could join him in Holland, and she took a job in a pensions office. But at the start of 1919 she wrote to Lancelot. With acute pleasure she told him that she would not need his money any more, because she was getting married. Lancelot asked to see her. ‘I hate to say this,’ he said, ‘but I feel I have to. M. Lenglet is not a suitable person for you to marry.’ ‘You don’t know anything about him,’ Ella said. But, strangely he did. Lancelot had been made a CBE, for his service on several important wartime committees: the most powerful of these was the Contraband Committee, which directed the blockade of Europe. Well, what had Jean been doing? After fighting at Verdun, he had been recruited into the Deuxième Bureau; he was, in fact, a French secret agent. But none of this did Ella know. ‘There are several things I can’t tell you,’ Lancelot said, ‘but if you marry him you’ll be taking a very big risk.’ ‘I like taking big risks,’ Ella said. ‘Didn’t you know that?’ She had to leave most of her clothes behind, because she couldn’t afford to pay the seamstress who was making them. But she sailed for Holland with a feeling of triumph and gratitude. It had taken over ten years—but she had escaped at last. She would never return to England. No matter what: never.

Photo: | Taylor Gray, Unsplash

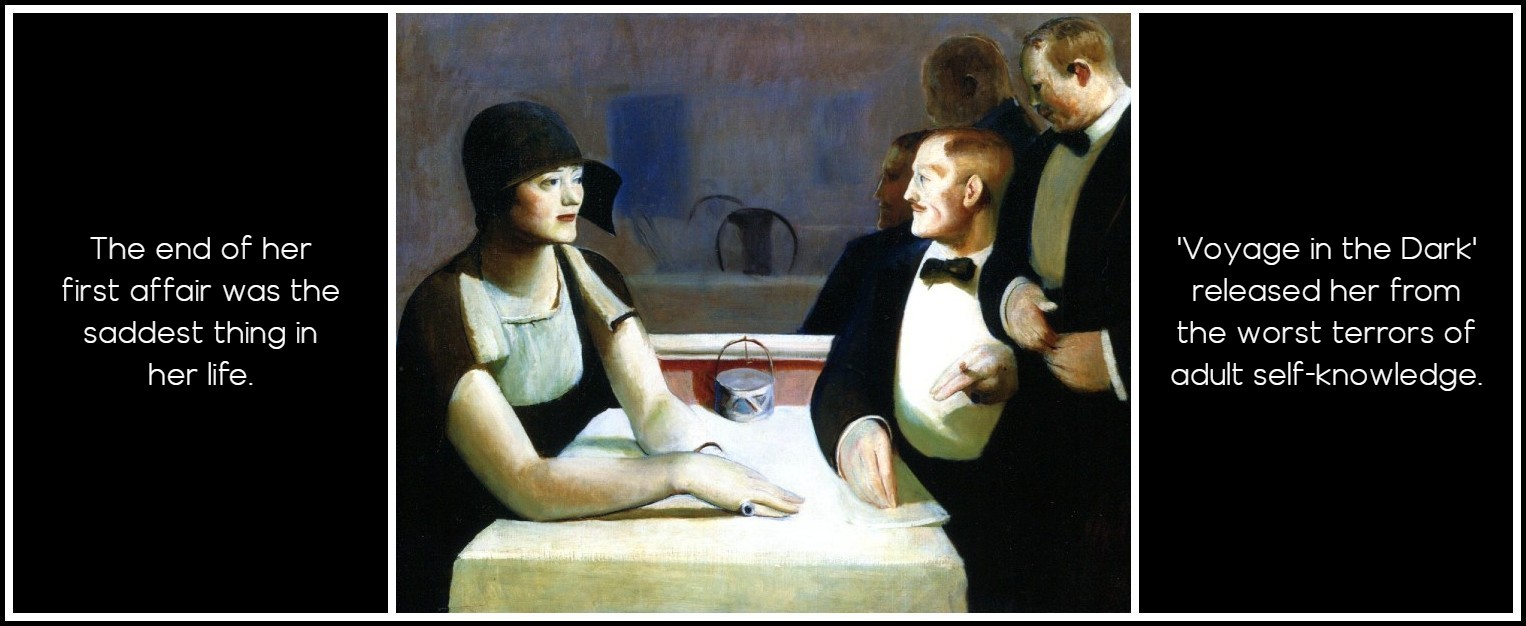

Despite all Lancelot’s kindness (Jean had gone back to him for help at least once and perhaps more often), the English gentleman who had been her greatest love became her worst enemy, and the last person she could forgive. That is one reason, perhaps, why Walter Jeffries in Voyage in the Dark is duller and less sensitive than Lancelot had been in 1910—because Lancelot had made himself duller and less sensitive, the last time (or times) that Jean had seen him, before she wrote the book. For Voyage in the Dark was the novel she turned to now, in the early 1930s. Ford had said about the notebooks of her first diary, ‘You’ll need those. Don’t tear them up or anything silly like that’, and she hadn’t. She took them out now, and began to write. The end of her first affair was the saddest thing in her life; still, writing Voyage in the Dark was easier than usual. Going back so far—twenty years for the affair, and even more for her memories of childhood—gave her the relief of distance; but it was more than that. Voyage in the Dark released her from the worst terrors of adult self-knowledge, which she had begun to pursue before it, in Mackenzie, and would go on pursuing after it again. Anna Morgan is still young and pretty; she doesn’t drink, or make scenes, or hate anyone. She is a victim of other people—as Marya is, in Quartet, but she is not yet as bitter and angry as Marya. She is an innocent victim: of Walter, who is weak and cowardly; of Vincent, who is a smug and smiling villain; of Hester and Ethel and Carl.

Guy Pène du Bois, Mr. and Mrs. Chester Dale Dine Out, 1924

Surely that is why Voyage in the Dark came easily—at least, more easily than the others; and why it always remained Jean’s favourite among her novels. It is a lovely book—sad and funny, simple and yet complex; written ‘almost entirely in words of one syllable’, as Jean said, yet richly interweaving past and present, reality and dream. It is a perfect novel, but a small one; and perfect and small for the same reason— that in it Jean reduced the task she set herself, to learn the whole truth about herself and her suffering. Voyage in the Dark is only half the truth, the half that said things were other people’s fault. It is therefore only a sad novel, and not a painfully angry one—for Jean’s real anger was reserved for herself. And so it is perhaps her most charming novel, and the easiest one to read: but it is not her best or most important. She was at the peak of her powers as a writer, and it was as good as it could be without being wholly true. For that rare combination of greatest skill with greatest truth we have to wait for Good Morning, Midnight and Wide Sargasso Sea.

Photo: Christian Quadt, Unsplash

Voyage in the Dark came more easily to Jean than the others, but it did not come easily. Nothing did any more. She ‘had the horrors about it and about everything for a bit’; during its writing she sometimes drank two bottles of wine a day. As always, she had great trouble finding an ending—and when she finally found one, the publisher made her change it. She spent several dismal weeks over those last four lines, and felt ever after that they had been a mistake—and a betrayal. Voyage in the Dark came out in 1934; it was well received, but her pleasure in it was spoiled. That was to be the pattern with her books from now on.

Photo: Feodor Chistyakov, Unsplash

CAROLE ANGIER: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments