Theoretical Framework and Overview

JEAN RHYS: WOMEN, MELANCHOLIA AND NOSTALGIA – PART 1

Cathleen Maslen

From Cathleen Maslen, ‘Too Late for Truth: Women, Melancholia and Nostalgia in Jean Rhys’ in her book Ferocious Things: Jean Rhys and the Politics of Women’s Melancholia

(Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009) pp. 1-16

Jean Rhys, 1977 | Photo: Paul Joyce

I. INTRODUCTION

In reading and thinking about the works of Jean Rhys, it is surely impossible to overlook the theme of melancholia. Since the publication of Wide Sargasso Sea in 1966 and Rhys’s return to literary prominence alter decades of obscurity, a large body of critical and academic writing on her works has accumulated, and it would be difficult to locate among these many interpretations a reading in which the melancholy of Rhys’s protagonists was not at least mentioned. But looking beyond the obvious melancholia of her characters, late twentieth-century studies of Rhys have also sought to contextualize and theorize the instability of identity, which is itself a melancholic premise. Recent readings of Rhys are often guided by post-colonial, post-structuralist and/or feminist theories of identity, and considerable attention is also given to Rhys’s specifically modernist inscription of identity and character. Coral Ann Howells, for example, implicates all these approaches in her interpretation of Rhys’s work, arguing that ‘what Rhys constructs through her fiction is a feminist colonial sensibility becoming aware of itself in a modernist European context, where a sense of colonial dispossession and displacement is focused on and translated into gendered terms, so that all these conditions coalesce, transformed into her particular version of feminine pain.’1 It is my wish to accommodate, as much as possible, these refinements of the Rhysian protagonist’s positionality, but with a particular focus upon the politics of Rhys’s portrayals of women’s melancholic identification and nostalgia.

1 – Coral Ann Howells, Jean Rhys (Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1991)

Photo: Getty Images for Unsplash

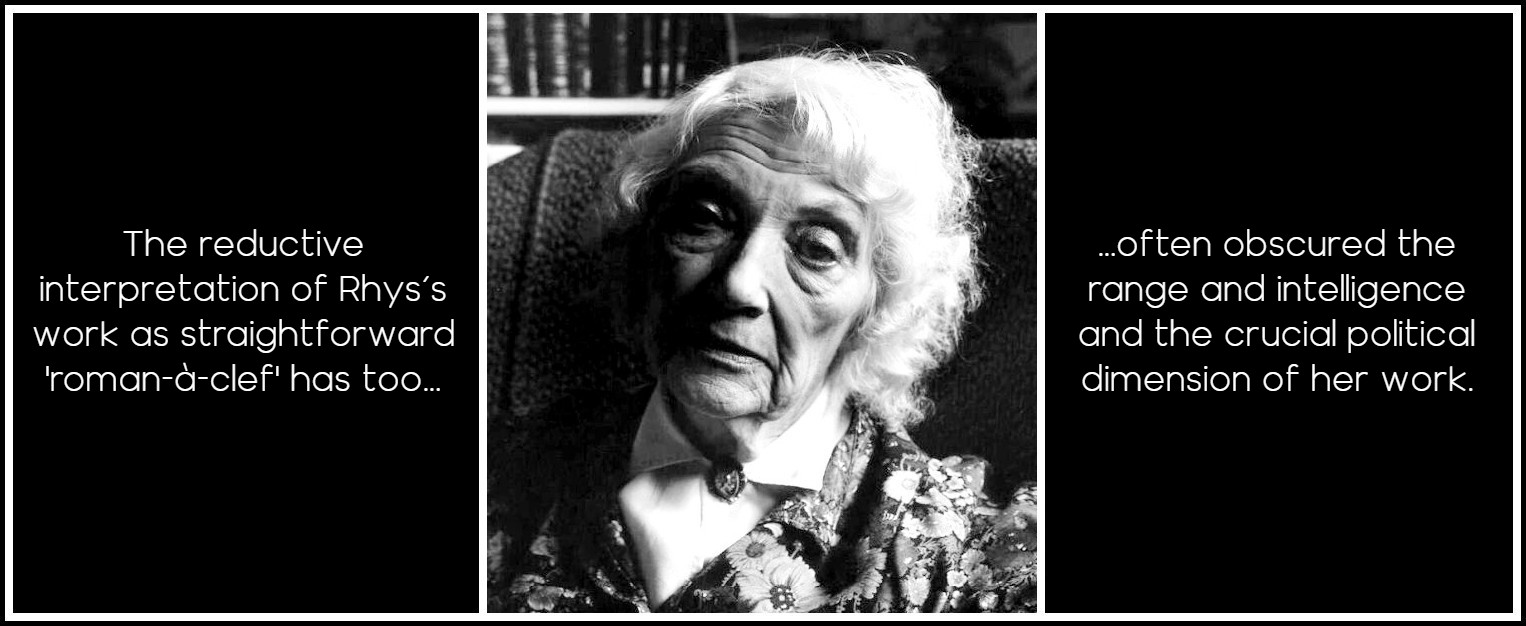

Before elaborating upon my own approach, I should emphasize that wherever possible, my interpretation of Rhys’s works will minimize what might be thought of as Rhys’s ‘melancholic biography’. However, I am not devaluing efforts to historicize Rhys’s work through close examination of her Anglo-colonial background and socio-cultural positioning as an émigré in England. This is always relevant because it illuminates the wider social, political and cultural context which enabled Rhys’s writing. Moreover, there is no denying that Rhys’s novels were deeply personal, and it is not surprising that many critics and readers of Rhys, both past and present, have felt compelled to consider her work with close reference to her difficult life. However, as Helen Carr has argued, the reductive interpretation of Rhys’s work as straightforward roman-à-clef has too often obscured ‘the range and intelligence and the crucial political dimension of her work.’1 As it is my intention to focus upon the political and theoretical dimension of Rhys’s writing of melancholia, I will not be analyzing Rhys’s own struggle with depression to any great extent, as a great deal has been written on this subject, and most of it has little bearing on my particular approach to her work.

1 – Helen Carr, Jean Rhys (Plymouth: Northcote House, 1996) 5

Jean Rhys, 1977 | Photo: Paul Joyce

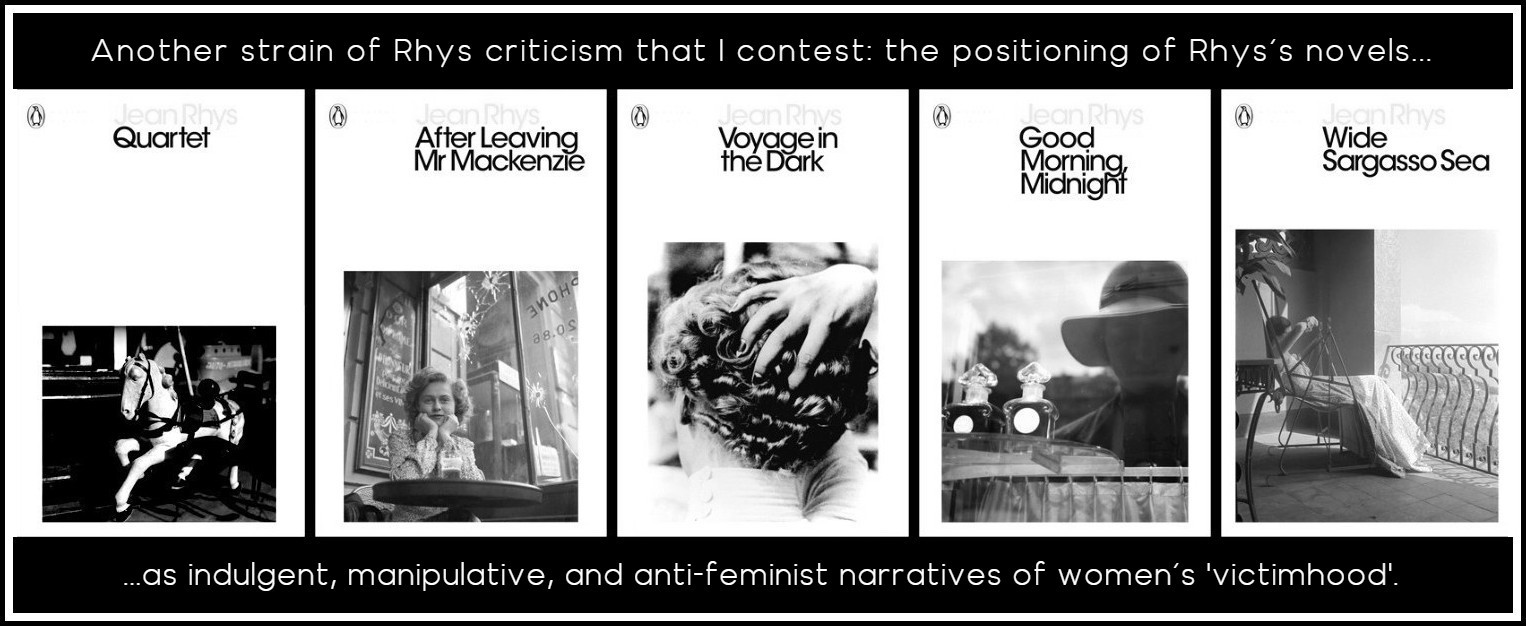

There is another strain of Rhys criticism that I should like to contest; that is, the positioning of Rhys’s novels as indulgent, manipulative and anti-feminist narratives of women’s ‘victimhood.’ It is no simple matter, as a feminist reader, to completely eschew such interpretations, as they are often proposed by credible feminist writers and critics impatient with the passivity, pessimism and purported ‘masochism’ of Rhys’s protagonists. For example, Laura Tracy suggests that Rhys, as an angry and depressed woman, is committed to the punishment and abasement of her own fictional characters. ‘The relationship between narrator and protagonist in Rhys can also be comprehended as a sadomasochistic partnership.’1 Tracy’s reading seems guided by the biographical bias that I have just discussed, for when she suggests that ‘female readers of Rhys have attached themselves to someone who uses power insidiously’, there can be no doubt that Rhys’s personal psychology is just as much at issue in Tracy’s criticism as are Rhys’s texts themselves.

1 – Laura Tracy, ‘Catching the Drift’: Authority, Gender and Narrative Strategy in Fiction (New York: Rutgers University Press 1988), p 42-43

Jean Rhys’s Five Novels: Penguin Covers

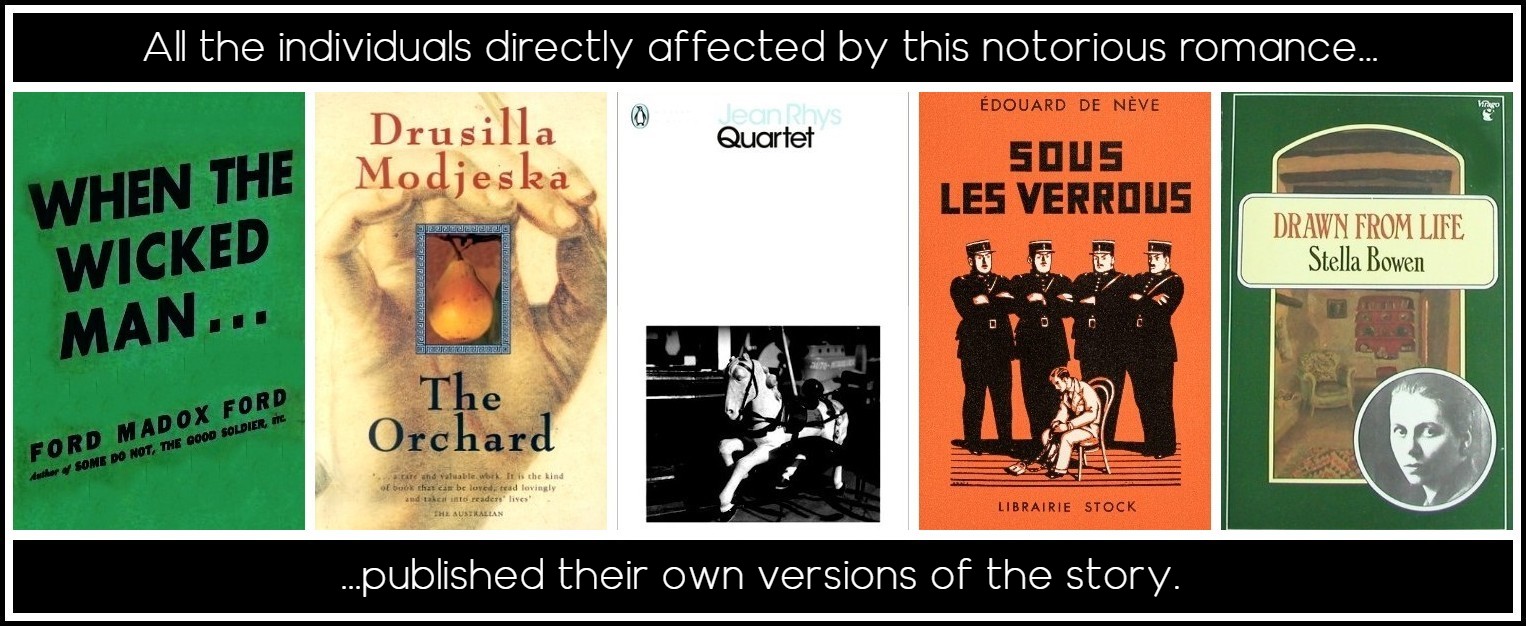

This biographically influenced judgement of Rhys’s texts as reinforcing, rather than interrogating, the politics of feminine victimhood recurs in Drusilla Modjeska’s novel, The Orchard. In a ficto-critical meditation, ‘The Adultery Factor,’ Modjeska irascibly positions Rhys’s first novel, Quartet, as a distorted and malicious memoir of its author’s sexual relationship with Ford Madox Ford. Modjeska is particularly interested in rescuing Ford’s de facto wife, Australian artist Stella Bowen, from Rhys’s unflattering portrayal of the Fords and their circle. Remarkably, all the individuals directly affected by this notorious romance published their own versions of the story. Aside from Rhys’s Quartet and Stella Bowen’s autobiography, the affair was also fictionalized by Rhys’s first husband, Jean Lenglet, in his novel Barred, published under the pseudonym of ‘Edouard de Nève’ and translated by Rhys herself. Moreover, Ford Madox Ford’s novel, When the Wicked Man, features a stereotypically erotomaniac white Creole, Lola Porter, who is thought by many critics to be a hostile depiction of Rhys.

Ford Madox Ford, When the Wicked Man | Drusilla Modjeska, The Orchard | Jean Rhys, Quartet | Edouard de Nève, Sous les verrous | Stella Bowen, Drawn from Life

Perhaps because of this sensational profusion of texts, Rhysian scholarship has been burdened with anxieties as to the ‘true story’ of Quartet. ‘The Adultery Factor’ is a slightly vulgar example of this critical curiosity. Modjeska claims she is interested in exploring the disempowerment of women in heterosexual love triangles with reference to the fraught ménage à trois of Rhys, Bowen and Ford. However, her analysis devolves into a partisan comparison between the art and life of Rhys and Bowen respectively, in which Rhys is denigrated as pathological and weak, and Bowen praised for her balanced, self-emancipatory response to sexual betrayal: That Stella Bowen came out of this story better than Jean Rhys is because she learned from it the nature of the dance in which she was engaged and stepped outside her own complicity in an objectified role. So when Bowen says in her autobiography that we should learn to stand alone, she doesn’t just mean because men let us down, but that to develop this capacity is an integral part of our quest to become fully ourselves. According to Modjeska, Rhys failed to attempt the ‘quest to become fully herself. She foundered in her own victim pleasures; she was underhand and manipulative.’ Conversely, Bowen’s account of her emotional recovery from Ford’s sexual betrayal in her autobiography is praised by Modjeska for subverting sado-masochistic narratives of women’s suffering.

Drusilla Modjeska

Modjeska’s criticisms of Rhys emphasise the unpalatable instability of identity in Rhys’s narratives. Endorsing the feminist-individualist aspiration to ‘become fully oneself,’ Modjeska would seem to accept without question that there is always a pre-given female transformation paradigm, or emancipating model of self, available for victimized women to embrace. All that is needed, it is implied, is a willingness to assert or, as it were, to activate this dormant liberated identity—an assumption which, I would suggest, intimates a potential teleological value, and therefore a sort of duty of optimism, inhering in all female trauma. That is, trauma provides for the dynamic emergency that, given its chance (as opposed to ‘manipulatively’ resisting the latent opportunity of trauma) yields the ‘full’ or realized feminine self.’ Rhys, on the contrary, often seems to make a point of contesting, or at least casting doubt upon, the capacity of her protagonists to give trauma such meliorist or redemptive shapes. More disconcertingly still, Rhys’s work often suggests that identity itself may consist in an interminable emergency or incompleteness, which is in fact more consistent with at least the psychoanalytic understanding of ‘trauma’—that is, the status of trauma as a recurrence of an originary wound, psychic or otherwise, which in its repetitiousness manages to defer ‘closure’ and recovery. Meditating upon traumatic events, Vijay Mishra suggests that ‘re-arrangement, re-inscription or deferred revision works best precisely in those moments, events, memories that are not fully incorporable in a meaningful context’.1 To be sure, trauma that resists ‘meaningful context’ (here exemplified by Modjeska’s rather vague idea that one might become ‘fully oneself’) entails difficulties and suffering, but nonetheless it may generate more ambiguous, fluid and subversive experiences and apprehensions than Modjeska’s latitudinous progress from womanly trauma to feminist triumph.

1 – Vijay Mishra, The Literature of the Indian Diaspora: Theorising the Diasporic Imaginary (New York: Routledge, 2007) 114

Jean Rhys

This in mind, I suggest that such castigations of Rhys or Rhys’s characters for refusing to construct victimization as an opportunity for staging victorious self-affirmation are often premised on cultural as well as psychological generalizations. One needs to ask precisely what is meant by (as Modjeska puts it) the ‘female quest to become fully ourselves.’ What this quest or struggle might entail from a mainstream feminist point of view might aptly be exemplified by Stella Bowen’s own autobiographical meditations: Why did not my godfathers and godmothers in my baptism, and my copybooks at school, and my mother when she tried to explain the facts of life, all tell me, ‘You must stand alone’? Elsewhere, in parenthesis, Bowen remarks that ‘in the last resort you must be responsible for yourself. How trite it sounds, how not worth mentioning! But what a discovery it makes!’ But what is needed in order for one to ‘take responsibility for oneself’? As Bowen’s (albeit critical) summary of her bourgeois upbringing implies, it would seem that one needs people and institutions that bolster the value of one’s individuality, through extolling education and providing stable cultural beliefs (‘the facts of life’). However, Bowen’s individualism and cultural values are hardly universal, and even in this particular Western bourgeois context, the ‘functional’ family that successfully instils such values cannot be taken for granted. In other words, Bowen’s self-recuperative feminism does not take into account the doubtful viability of liberal discourses of feminine self-esteem for all women in every socio-cultural situation.

Stella Bowen

This problem is highlighted by Sue Thomas in her essay, ‘Adulterous Liaisons: Jean Rhys, Stella Bowen and Feminist Reading.’1 Thomas situates Bowen’s confidence and optimism in the context of ‘informal liberal education,’ and ‘middle class feminist individualism.’ The seminal text of egalitarian feminism in the Western academy is perhaps Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1790). Wollstonecraft’s polemic was, of course, informed by late 18th century Enlightenment discussions concerning natural (as opposed to class-dictated) human rights. As Wollstonecraft emphasises throughout her Vindication, the evolving political ideologies of the Enlightenment were at best marginally interested in women’s entitlements. Indeed, Enlightenment ideologues such as Rousseau were capable of essentializing the ‘natural’ inferiority of women in the same breath as they argued for the natural equality of men. By way of meditating upon Bowen’s investment in ‘middle class feminist individualism’, it is perhaps worth noting that Wollstonecraft, impatient with a proliferation of etiquette primers addressed to aristocratic ‘ladies’, explicitly states that her Vindication is addressed (‘in a firm tone’) to the women of the middle classes, because, Wollstonecraft suggests, ‘they appear to be in the most natural state’.

1 – Sue Thomas, ‘Adulterous Liaisons: Jean Rhys, Stella Bowen and Feminist Reading,’ Australian Humanities Review 22 (June-August 2001)

Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1790

Bearing in mind that the connotations of terms such as ‘middle class’ and ‘natural’ shifted dramatically between the 18th and early 20th centuries, it is perhaps worth comparing the previously-cited excerpt from Bowen’s Drawn from Life with Wollstonecraft’s ‘rough sketch’ of her intentions in her Vindication. Bowen, as we have seen, reproaches her educators for not teaching her to ‘stand alone’: Wollstonecraft’s treatise, written almost two hundred years before Bowen’s memoir, presciently describes the ideal liberal-feminist education which Bowen misses, on occasion using identical phrasing: My own sex, I hope, will excuse me if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone. I wish to persuade women to endeavour to acquire strength, both of mind and body, and to convince them that the soft phrases, susceptibility of heart, delicacy of sentiment and refinement of taste, are almost synonymous with epithets of weakness. The first object of laudable ambition is to obtain a character as a human being, regardless of the distinction of sex.

Maggi Hambling, A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft, 2020 | Newington Green, London

In referring to qualities such as ‘susceptibility of heart, delicacy of sentiment and refinement of taste,’ Wollstonecraft is probably alluding to the cultural obligation of middle class women to project a subdued, ‘genteel’ sexuality in order to function as palatable objects in exchanges of courtship and marriage. However, in the context of this discussion, it is worth noting that these ‘epithets of weakness,’ as Wollstonecraft calls them, are also apprehended by Western literature, philosophy and medicine as melancholic traits. These stereotypically ‘feminine’ qualities, along with related psychological propensities such as sensitivity, ‘nervousness’ (that is, intense emotional reflexivity), self-deprecation, self-reproach, mournfulness, and perhaps above all a tendency to aestheticize sadness, function and signify for both men and women, but in a strictly binarizing fashion, registering gender in terms of emotional intelligence or the lack of it. To elaborate, women’s sadness is objectified—it is received as a piteous, beautiful and/or deplorable spectacle of suffering, or possibly (as Wollstonecraft seems to hint) as a strategy of coquetry. The discourse of masculine melancholia also allows for men to display sadness, but such spectacles are almost always ennobled by the purported ‘subjective reaches’ of the melancholic man, who, as Sue Thomas notes in her essay on Rhys’s short story ‘Till September, Petronella,’ is supposedly distinguished by his ‘exceptionality, genius, individuality.’1

1 – Sue Thomas, ‘Thinking Through “The grey disease of sex hatred”: Jean Rhys’s “Till September Petronella”’, Journal of Caribbean Literatures 3.3 (Summer 2003), 80

Munch, Melancholy, 1894

There is nothing particularly original in the observation that womanly melancholia, or feminine articulations of victimization and sadness, almost never signify as anything other than the tedious pathology of ‘depression’, or, worse still, sexual manipulation and self-indulgence (as in the moralizing meditations of Stella Bowen and Drusilla Modjeska). Feminist scholars and writers have already given considerable attention to the discrepant moral and intellectual accreditation of male and female melancholia respectively. Nonetheless, I believe this problematic gendered evaluation of sadness, which has been so widely remarked with so little impact, is worth reiterating. Rhys’s positioning of women as melancholic subjects represents a provocative rejection of cultural trivializations of female suffering, as well as an attempt to usurp the psychological dignity and perceptiveness accorded to male melancholia alone. It should also be emphasized that this attempt is largely unsuccessful. All of Rhys’s novels are permeated with the protagonists’ desire to signify loss, sadness and suffering outside sadistic parameters of sexual objectification, but more often than not, these cultural parameters prove profoundly resistant to the feminine aspiration to an articulate melancholic identity. Moreover, the melancholic personae and paradigms with which these characters identify are often laden with racist and colonialist ideology as well as misogyny. Given Rhys’s protagonists’ ambiguous racial and ethnic status, it is not surprising that when these characters evince a fundamentally Eurocentric discourse of elite melancholia, unanticipated conflicts of interest and representational dissonances ensue. However, these dissonances are to some extent instructive, as they not only expose what Juliana Schiesari has termed ‘the gendering of melancholia,’ but also the racing of melancholia—in short, the possibility that the grand malaises of melancholia and nostalgia make critical discursive and ideological contributions to the related projects of imperial and masculine dominance.

Guy Pène du Bois, The Doll and the Monster, 1914

II. FEMINISMS, RACE AND MELANCHOLIA

Recent feminist theory concedes that seminal egalitarian Western feminism such as Mary Wollstonecraft’s, which reverberates in many texts by celebrated, canonical women authors, exhibits an insidious Eurocentrism: likewise, it is widely admitted that this problem must be addressed if feminist politics are to retain potency and relevance. Wollstonecraft herself proclaims she is addressing the Vindication to ‘civilised women of the present [18th] century.’ That these women are European women may be deduced from Wollstonecraft’s unabashedly orientalist rhetoric, in which female subordination is deplored because, among other things, it is fundamentally un-Western. The ‘civilised’ female subjects Wollstonecraft seeks to vindicate are oppressed ‘in the true spirit of Mahometism’, while savagely sensualist male ‘tyrants’ convert women into ‘slaves’ or petty manipulators, akin to ‘Turkish bashaws’. As I mentioned, by her own admission Wollstonecraft is interested primarily in reforming middle-class, civilized women: her polemic disparages ‘Eastern’ misogyny not in order to address the predicament of its non-white victims, but rather to embarrass institutionalized white sexism with a pernicious racial comparison.

John Opie, Mary Wollstonecraft, 1797

Another relevant example of problematic egalitarian feminist writing in connection with Rhys’s work is Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, which Rhys famously appropriated to produce the narrative of Wide Sargasso Sea. Jane’s intellectual and emotional equality with Mr Rochester is perhaps one of the novel’s major themes. Nonetheless, her meditations or pronouncements upon her own merits are nearly always elicited by Rochester, who acts as the masculine interlocutor enabling and legitimizing Jane’s self-esteem. This is perhaps most memorably exemplified when Rochester broaches the question of marrying Jane, which she initially understands as a sadistic joke (‘you play a farce)’. Speaking under this assumption, Jane passionately defends the gravity of her feelings and her human equality: Do you think I am an automaton?—a machine without feelings? And can bear to have my morsel of bread snatched from my lips, and my drop of living water dashed from my cup? Do you think because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! I am not talking to you now through the medium of convention, custom, conventionality nor even of mortal flesh; it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God’s feet, equal—as we are!’.

Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, Penguin Classics

With respect to Rhys’s recuperative representation of Bertha, Rochester’s abhorred first wife, it is worth noting that the subjective propensities Jane insistently claims—here inscribed in terms of ‘soul’, ‘heart’, ‘spirit’ and above all, ‘equality’—are also insistently negated in Brontë’s characterization of Bertha, a Jamaican Creole. Bertha’s characterization is chiefly conveyed in the tortured mnemonic account of Rochester’s marriage that he provides for Jane’s benefit. Bertha, he says, has ‘not one virtue in her nature’ she is ‘common, low, narrow and singularly incapable of being led to anything higher’; she has a ‘pigmy intellect’ combined with ‘giant propensities’ for ‘unchaste’ sex and the pursuit of ‘intemperate’ appetites. The ‘pigmy intellect’ allegation, along with Rochester’s catalogue of stereotypically black vices, seems to imply his suspicion of Bertha’s non-whiteness or racial ‘miscegenation’, which in turn is intrinsically linked to Bertha’s ‘inhuman’ quality (Jane hears Bertha ‘gurgling’ and ‘moaning’, while her laughter is ‘demoniac’ and ‘goblin’).

Creole Woman, 1860

In her famous essay, ‘Three Women’s Texts and a Critique of Imperialism’, Gayatri Spivak draws our attention to the manner in which Brontë’s Bertha is ‘sacrificed as an insane animal for her white sister’s consolidation’, and proceeds to warn the European feminist against investing in an identity politics that privileges the Western-rationalist discourse of individualism: As the female individualist articulates herself in shifting relationship to what is at stake, the ‘native female’ as such (within discourse, as a signifier) is excluded from any share in this emerging norm. From Spivak’s deconstructionist perspective, as in points of view articulated through Marxist, feminist and post-colonial thought, the Enlightenment ideologies of inalienable individual rights are understood as privileging the propertied white male above all other subjects. While, as Spivak notes, and Wollstonecraft exemplifies, there is room in this discourse for the Anglo-American middle class feminist, the less privileged non-white female has little (if any) access to this Eurocentric narrative of subjecthood. Accordingly, Spivak urges the feminist reader to ‘wrench herself away from the mesmerizing focus of the “subject constitution” of the female individualist’.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Turning now to the racial politics of egalitarian modernist feminism, from which Rhys controversially departs, it is worth noting Sue Thomas’s discernment of an insidious celebration of ‘Anglo-Saxonism’ in Stella Bowen’s previously mentioned memoir, Drawn from Life. Referring to Benjamin Kidd’s Social Evolution, Thomas makes intriguing connections between Bowen’s disparagement of Rhys and her values and an implicit affinity with an ‘Anglo-Saxon’ ethic. Anglo Saxon culture, in Kidd’s text, is associated with ‘humanity, strength, an uprightness of character and sense of duty’. It should be emphasised that ‘strength’, ‘uprightness’ and in particular a ‘sense of duty’ are stereotypical markers of healthy and proper male behaviour and psychology. The association of implicitly male virtues with ‘Anglo-Saxonism’ overtly excludes non-Anglo-Saxons, and by implication women, from the ethical high ground and, perhaps, ‘humanity’, or at least the ethical behaviour appropriate to humans. Paradoxically, Bowen (and, by extension, Modjeska) re-calibrate this implicitly ‘men only’ discourse of morality as the most laudable remedy for specifically female travail. Ironically, Rhys’s alternative strategy of negotiating trauma through melancholic behaviour, such as lamentation, introspection, and cynicism or world-weariness, also refers to a conventionally masculine attitude: this irony is intensified by the point that, as Juliana Schiesari has noted, the male melancholic or homo melancholicus actually appropriates and redeems a ‘feminine’ position under the guise of ‘sensitivity’ or ‘nostalgia’ or ‘loss’.

Giorgio de Chirico, Les jeux terribles, 1925

III. THE MASCULINIST CULT AND CULTURE OF MELANCHOLIA

Juliana Schiesari’s The Gendering of Melancholia: Feminism, Psychoanalysis and the Symbolics of Loss in Renaissance Literature) has helped considerably in shaping my ideas concerning melancholia as a cultural as well as psycho-clinical phenomenon. In the early 1990s, Schiesari noted two main disciplinary and methodological groups of thinkers interested in melancholia: ‘In one camp are contemporary theorists of melancholia largely informed by psychoanalysis; in the other, Renaissance scholars interested in the iconographical and historical issues relevant to a condition once characterized by humoral medicine as “an excess of black bile”.’ Schiesari adds that ‘despite the obvious confluence of interests, research by these two groups never meets’. In recent years, however, cultural theory has been increasingly interested in contemplating the humanist, psychoanalytical as well as post-modern resonances of the term ‘melancholia’, often intersecting these discourses with a view to recognizing the suffering of victims of specific historical traumas, but also as a means of interrogating ‘whitewashing’ nostalgias for violent nationalisms.

Juliana Schiesari, Gendering Melancholia, 1992

Some notable examples of such work include Eric Santner’s Stranded Objects: Mourning, Memory and Film in Postwar Germany, a fine anthology of mourning theory; Loss: The Politics of Mourning, edited by David Eng and David Kazanjian; Jennifer Radden’s The Nature of Melancholy: from Aristotle to Kristeva, and most recently, Paul Gilroy’s After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture?. Broadly speaking, this relatively recent field of ‘mourning theory’ is concerned with the political and cultural acknowledgment of historical trauma endured by marginalized peoples, exploring the extent to which melancholia is a ‘healthy’ and/or politically appropriate response to such suffering, and in particular raising the question of who (if anyone) is entitled to ongoing identification with suffering and loss. Gilroy, for example, aims to ‘consider how a deliberate engagement with the twentieth century’s histories of suffering might furnish a peaceful accommodation of otherness in relation to fundamental commonality,’ and in this spirit presents a polemic that resists, as Gilroy puts it, the ‘exaltation of victimage or the world-historic ranking of injustices that always seem to remain the unique property of their victims’.

Paul Gilroy, After Empire | David Eng & David Kazanjian, Loss | Eric Santner, Stranded Objects | Jennifer Radden, The Nature of Melancholy

I will now briefly sketch the Western evolution of melancholia in order to give a sense of its narrativization as a kind of gift, signifying heightened powers of insight and ethical superiority. The classic and seminal exaltation of melancholia is to be found in Aristotle’s Problemata, in which he poses the question: ‘Why is it that all those who have become eminent in philosophy or politics or poetry or the arts are clearly of an atrabilious temperament, and some of them to such an extent as to be affected by diseases caused by black bile?’ Commenting on this famous passage, Stanley Jackson suggests that Aristotle was instrumental in introducing into humoral theories of depression (then thought to be the consequence of an excess of ‘black bile’) a privileged connotation: melancholia was ‘a temperamental disposition to outstanding accomplishment.’ The reverent attitude towards melancholia in classical thought was to some extent attenuated by medieval Christianity, which positioned despair (and its concomitant, suicide) as the most grievous of sins and reconceptualised melancholia as deplorable ‘acedia’. As Jackson points out, the idea of acedia was complex and sometimes self-contradicting, encompassing ‘sorrow-dejection-despair and neglect-idleness-indolence’.

1 – Stanley W. Jackson, Melancholia and Depression from Hippocratic to Modern Times (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986) 33

Aristotle | Roman copy from the Greek original

During the Renaissance, however, neo-classical thinkers and writers revived the celebratory discourse of melancholia. As Jackson and Schiesari both suggest, the return of the melancholic man in an admirable guise—as a martyr to his own genius and sensitivity—was likely to have been connected with a secularist interest in the human condition, and the declining importance of the Christian God in the European world view. Marsilio Ficino epitomized this new humanism, seeking to reconcile Christianity with neo-Platonism. Ficino was particularly interested in rehabilitating Aristotle’s admiring attitude towards melancholia for the benefit of his contemporary scholars. In his influential work, De Vita Libri, he argued that melancholia, while burdensome, facilitated literary genius. Lawrence Babb notes that the first book of De Vita Libri is largely dedicated to ‘teaching the scholar how to keep his melancholia happily tempered.’1 For Ficino, counter-productive acedia could be cultivated, by means of spiritual discipline as well as humoral medicine, into noble, saturnine melancholia, This idea hints at the intrinsic self-consciousness of the scholarly and literary melancholic persona.

1 – Lawrence Babb, The Elizabethan Malady: A Study of Melancholia in English Literature (Michigan State University Press, 1951) 61

Marsilio Ficino, Teologia Platonica, 1482

Robert Burton’s labyrinthine Anatomy of Melancholy might seem a more egalitarian celebration of the illness, inasmuch as Burton discerns melancholia in almost every conceivable occupation, emotion and social context: ‘So take that Melancholy in what sense you will in disposition or habit, for pleasure or for pain, dotage, discontent, fear, sorrow, madness, for part or for all, truly or metaphorically, tis all one.’ The very expansiveness of Burton’s Anatomy suggests the intensity of popular as well as scholarly interest in this subject in the seventeenth century, and its fashionable connotations. However, Burton also promotes the more elitist, visionary notion of melancholia: ‘Concerning myself I can peradventure affirm, as Marius says in Salust, ‘that which others hear of or read of, I felt and practised in my life; they get their knowledge by books, I mine by melancholising.’ Interestingly, Burton also draws attention to the therapeutic nature of ‘luxuriating’ upon his own melancholia, suggesting that his suffering is mitigated by the pleasurable enterprise of inscribing it as a ‘subject most necessary and commodius’.

Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, 1621

Burton’s unashamed admission of such ‘luxuriation’ is a prototypical example of the legitimization of melancholic speech as a subject or art in itself, rather than as a manifestation of illness or a straightforward attempt to communicate sadness. Instead, melancholia becomes a privileged performance that distinguishes the sufferer from other, less insightful or even deluded individuals. At the same time, the pathological connotation is never discarded: as Lawrence Babb notes, ‘melancholy’ in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is an intensely equivocal term. While neither Ficino nor Burton are usually credited as forerunners of modern psychiatry, their ambivalence towards the melancholic syndrome certainly seems to carry over into modern psychoanalytic narratives of depression. This inheritance is perhaps best exemplified by Freud’s essay, ‘Mourning and Melancholia.’ Freud at once ridicules the loquaciousness of melancholic speech and celebrates the superior insight conveyed by the verbose melancholic ‘plaint’. It is worth emphasizing the contrast between melancholic eloquence and the retardation of speech that often characterizes clinical depression. What is notably excluded from both Renaissance and modern accounts of melancholia is a mediating discourse between the pathological narrative of depressive psychosis and the notion of superhuman melancholic ‘genius.’ The melancholic might be insane and inarticulate or eloquent and hyper-percipient: in both eventualities, he or she is completely alienated from society. These extreme stereotypes insist upon the apolitical and ahistorical status of melancholic identity. Indeed, they almost seem to function in order to preclude the idea of a social and cultural context or basis for melancholia, or its capacity to signify in a ‘reasonable’ or constructive way. In other words, the irremediable sense of inferiority, loss or trauma generated by distinct moments of historical violence or ongoing social and cultural oppression is generally not addressed in traditional theories of melancholia or conventional psychiatry. I would suggest that a connection between melancholia and oppressive social and cultural scripts and identifications should be kept in mind as we consider Rhys’s work, since the melancholia of the protagonists seems so ineluctably connected with their degraded status in hierarchies of gender, class and race.

Antonio Saura, Mirta, 1959

If the historical and cultural privileging of melancholia is kept in mind, it should start to become apparent how from the point of view of the marginal, othered subject, an appropriative performing of melancholia might represent a seditious gesture of resistance, even at the expense of the subject’s having to bear the pathological connotation of melancholia along with its more prestigious significances. As is apparent from my rudimentary account of the Western portrayal of melancholia, its accreditation as a mark of intellectual or spiritual exceptionality tends to overlap with the clinical accounts of melancholia as a disabling disease. As Jackson suggests in his comments on the Aristotelian account of melancholia, the latter’s envisioning of the melancholic as ‘someone special with great potential yet someone at high risk provides an important example of the often fine line between melancholic and depressive nature and melancholic or depressive disease’. This essentialist notion of melancholic ‘nature’ might be recast in terms of melancholia as a socio-cultural and discursive point of identification. Shakespeare’s Hamlet, perhaps the most iconic Renaissance homo melancholicus, emphasizes that the melancholic nature is readily assumed or performed, and that this performance can represent a (sometimes questionable) identification with trauma and loss:

Tis not alone my inky cloak, good mother,

Nor customary suits of solemn black,

Nor windy suspiration of forced breath,

No, nor the dejected havior of the visage

Together with all forms, moods, shapes of grief,

That can denote me truly. These indeed seem,

For they are actions that a man might play,

But I have that within which passes show;

These but the trappings and the suits of woe.

William Morris Hunt, Hamlet, 1864

The famous line, ‘I have that within which passes show’ lends a fruitful ambiguity to Shakespeare’s thematizing of melancholia. While, in one sense, Hamlet means that his sadness is intractably, inexpressibly within him (thus passing or exceeding all external ‘show’ of sadness), the phrase is also a pun that suggests an antithetical conceptualization of melancholia. That is, Hamlet’s pun seems to hint that melancholia is a condition that ‘passes’ (gestures, performances) can show or display, with considerable public impact. To a large extent, the critical question concerning the veracity of Hamlet’s madness proceeds from contrasts between Hamlet’s private melancholic lucidity and an exhibitionist ‘antic disposition’, which may or may not be feigned or ‘put on’. Perhaps a more relevant conundrum for contemporary literary scholarship to pursue might be Hamlet’s conspicuous ambivalence concerning the most appropriate and ethical way in which to represent an extremity of suffering that precludes social conformity, and, perhaps more importantly, how to resist facile social mitigation of this alienating suffering (‘casting off thy nighted colour’, as Gertrude says in Act I). Resistance to the loss of pain is too easily positioned as ‘madness’. In Hamlet’s case, certainly, it could be argued that the ‘reality’ of his madness is less at issue than the point that his family and culture pathologizes him because he refuses to lose his loss, as it were.

Manet, Portrait de Faure dans le rôle de Hamlet, 1877

It may be seen that Hamlet’s ineffable problem of self-representation, and the melancholia that both generates and expresses it, carries over from Renaissance textuality into modernist inscription with surprising alacrity. T.S Eliot’s J. Alfred Prufrock explicitly corroborates with Hamlet, albeit in the context of denying affinity with the Prince: ‘No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be / Am an attendant lord, one that will do / to swell a progress, start a scene or two.’ In the best manner of melancholic irony, Prufrock’s devaluation of his own melancholia and ennui in relation to Hamlet’s manages to confirm the sublimity of his alienation. Like Hamlet, Prufrock is preoccupied with an apparent conflict between banal social performativity (‘prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet’) and his own insightfulness, with which he might, if he dared, ‘disturb the universe’. Significantly, this ‘universe’ consists in oppressively feminine (and feminizing) social obligation and ritual. Prufrock’s ‘Love Song,’ a title which conventionally might suggest a celebration of heterosexuality, functions ironically—indeed, almost sarcastically—to convey a mood of melancholic misogyny.

Augustus Edwin John, Sir William Nicholson, 1909

The depth of Prufrock’s intellect is suggested by his wish to broach an ‘overwhelming question’: he is prevented from pursuing his profound reverie by an apparently feminine voice which implores him: ‘Do not ask, let us go and make our visit’. This petty ‘visit’ is dominated by women ineffectually attempting ‘heavy’ conversation: ‘In the room the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo’. This rather facile rhyming couplet, reiterated at the end of the third stanza, is suggestive of relatively impoverished female intellects merely affecting profundity. The poem’s many images of repetitious and predictable feminine posturing (‘Arms that lie along a table, or wrap about a shawl’; elsewhere ‘settling a pillow or throwing off a shawl’) consolidate Prufrock’s stereotyping apprehensions of his female others. The poem concludes with a seemingly redemptive registration of femininity, but the gesture is confined io femaleness in its mythic guise as the melancholic man’s muse, and an unreliable muse at that: ‘I do not think they will sing to me. We have lingered in the chambers of the sea / By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown/Till human voices wake us, and we drown’. Funereally ‘wreathed’ with seaweed, these ‘sea girls’ or mermaids undoubtedly supply an image or performance of melancholic sublimity, but this spectacle, dislocated as it is from discrete masculine agency (they ‘do not sing’ to Prufrock personally), is ephemeral and fails to relieve the ennui of Eliot’s beleaguered protagonist. We cannot doubt, given the preceding verses, that the ‘human voices’ who wake and drown him are female ones.

Evelyn de Morgan, The Sea Maidens, 1886

Nonetheless, the eloquent misogyny of Hamlet and Prufrock inadvertently yields a model of melancholic identity which has proven open to appropriation by less culturally elite subjects. The way in which such melancholic ‘passes,’ gestures and performances can constructively signify both authentic feeling and self-bolstering display is usefully analysed by Anne Anlin Cheng in her subtle study, The Melancholy of Race. Cheng writes: When we turn to the long history of grief on the part of marginalized, racialized people, we see that there has always been an interaction between melancholy in the vernacular sense of affect, as ‘sadness’ or ‘the blues’, and melancholia in the sense of a structural identificatory formation predicated on—while being an active negotiation of—the loss of self as legitimacy. Racial melancholia as I am defining it has always existed for raced subjects both as a sign of rejection and as a psychic strategy in response to that rejection. Cheng suggests that we can read ‘racial melancholia’ as a sort of performativity without devaluing its authenticity or questioning the entitlement of the raced subject to melancholia. I should stress that Rhys’s white protagonists are not ‘raced’ in the same way as the Asian-American and Afro-American subjects of Cheng’s analysis, and I am not attempting to claim Cheng’s ‘racial melancholia’ on their behalf. Nonetheless, Cheng’s articulation of an intersection between incurring melancholic mood as a consequence of alienating or oppressive cultural positionality, and using melancholia as a self-consolidating strategy, is most useful for reading Rhys’s fiction. In Rhys there is always a tension between the protagonists’ authentic but unspeakable sadness and desire, and the seemingly inauthentic, or at least unsatisfactory, identities and discourses available for shaping and giving voice to these feelings. Rhys’s women suffer from a culturally-informed ‘melancholia of otherness’, as opposed to a private, pathological melancholia.

Jean Rhys

I should also emphasize that when I refer to the melancholic ‘performativity’ of Rhys’s protagonists, I am thinking about performativity in the Butlerian sense, as opposed to those melancholic ‘performances’ which have implications of ‘shamming’ in Hamlet, or merely replay futile objectification (in the manner of Prufrock’s mermaid muses). Butler insists that performativity ‘must be understood not as singular or deliberate “act”, but as the reiterative and citational practice by which discourse produces the effects it names.’ With this in mind, we might distinguish subversive melancholia from privileged canonical melancholia by observing how ‘reiterations’ of the latter by non-privileged subjects, such as Rhys’s protagonists, effect a disconcerting discursive reversal: such reiterations have the potential to restore subjectivity to those conventionally objectified by melancholic desire, as well as expose, as it were, the naturalized melancholic-humanist posture through disclosing its modality as a powerful identification strategy. At the same time, however, I wish to keep in mind that as a reiterative practice, the appropriation of melancholia is often intransigently marked by the dominant rhetoric of melancholia: it is no easy task, especially in Rhys’s work, to discern where unproductive mimicry of privileged sadness ends and transgressive representation of suffering begins.

Stanley Spencer, Daphne Spencer, 1951

CONTINUED IN JEAN RHYS: WOMEN, MELANCHOLIA AND NOSTALGIA – PART 2

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments