The Art of the Novel

MARIO VARGAS LLOSA ON D.H. LAWRENCE: AN INTERVIEW

Fletcher Fairey

From The Novel in the Americas, ed. Raymond Leslie Williams (Niwot, Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 1992) pp. 151-156

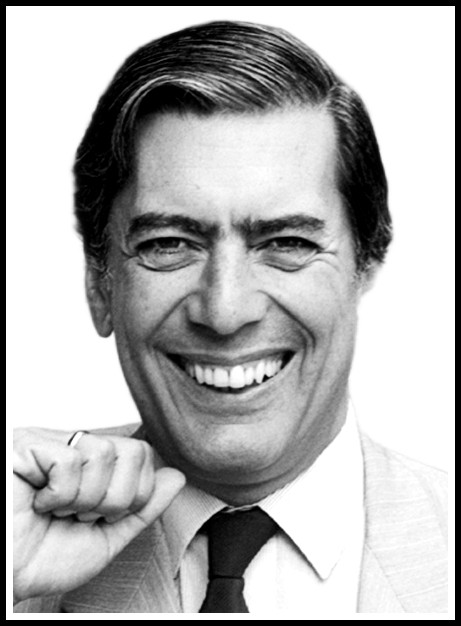

Mario Vargas Llosa, 1967 | Photo: M.C. Orive

I know that you have wanted to make a trip to the D.H. Lawrence ranch in Taos, New Mexico for some time. Why was a visit to a place where D.H. Lawrence spent a few years of his life, and where his ashes now reside, so attractive to you?

I am a bit of a literary fetishist. That is, I’m intrigued by the places and objects of writers’ experience. Especially in Lawrence’s fiction personal experience was important, and it’s fascinating to see firsthand a part of his life.

Have you had a lifelong fascination with Lawrence’s work? What were the circumstances of your first contact with his fiction?

I first read Lawrence as a university student in Lima in the 1950s. I read his novels Sons and Lovers, Women in Love, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover. I especially enjoyed his essays on American writers.

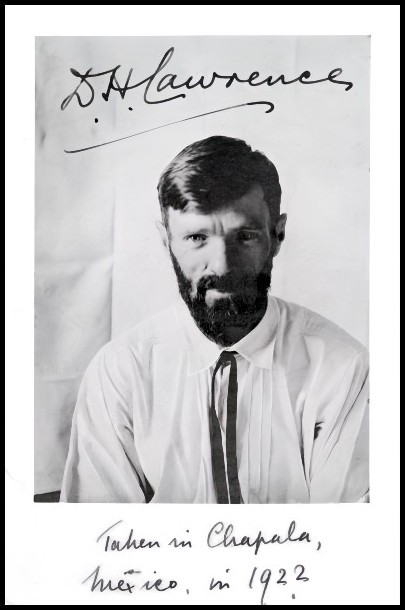

D.H. Lawrence in Mexico, 1922

Did you read these works in English, or were there Spanish translations available?

Victoria O’Campo’s publishing house, Sur, had many of Lawrence’s and other European writers’ works translated and published. I believe Borges translated The White Peacock. This was an important publishing house for writers of my generation. Therefore, these first readings in the 1950s were of translations.

Victoria Ocampo | Photos: Left & Right: Man Ray, 1929; Center: Gisèle Freund

There were subsequent readings of the English texts?

Yes. In fact, in London in the 1960s I read Lady Chatterley’s Lover in English, which improved the book considerably.

Was there anything in particular which initiated this return to Lawrence?

I came back to Lawrence after reading F.R. Leavis’ book on the English writer, a book which I found interesting but arbitrary, especially his fascination with the moral goals of Lawrence’s work. So I read Leavis’ book along with the corresponding Lawrence novels. I had also read a wonderful essay on Lawrence by André Malraux.

You are very acquainted with Lawrence’s work, and I know that Carlos Fuentes, Octavio Paz, and numerous other Latin American writers have also had interest in this writer. Why was your generation so attracted to Lawrence?

We read Lawrence primarily because he was a rebel. There was a mystique about Lawrence because of the censorship of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. We read Henry Miller for the same reasons.

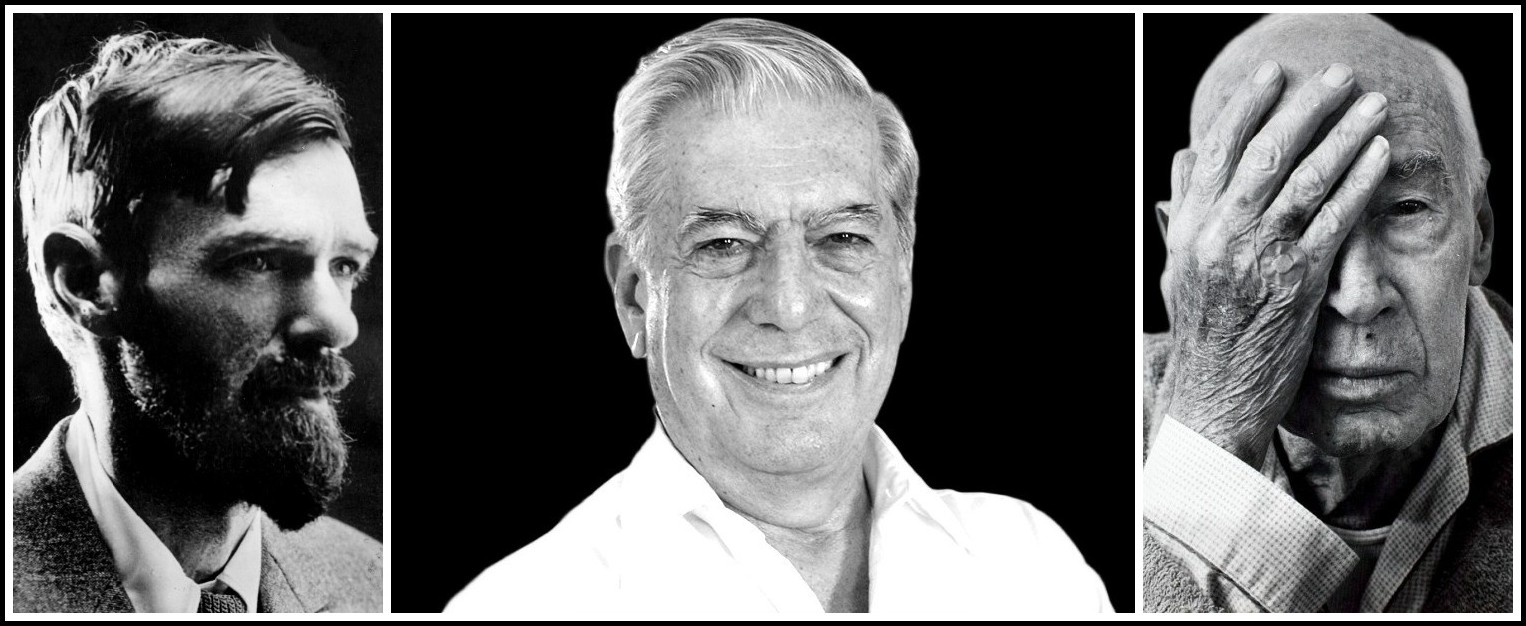

D.H. Lawrence | Mario Vargas Llosa | Henry Miller

It’s also interesting that he was a widely read and translated author in Latin America because some of his books, like The Plumed Serpent, seem to reveal a complete lack of cultural sensitivity.

The Plumed Serpent is Lawrence’s worst novel. It’s a failure because it shows a total incapacity to understand Mexico. The writing in that novel is kitsch. Lawrence didn’t understand anything about Mexico. Instead he fabricated something about this different world. However, you can compare this novel with other great novels, like Women in Love and Sons and Lovers, and some short stories because it shows a fascination with esoteric worlds.

I’m not sure that I understand exactly what you mean by ‘esoteric worlds’ in Lawrence’s work.

Lawrence is interesting because he discovered how to incorporate Freud’s theories on the unconscious and sexuality in his fiction. He dealt with his own secret sexual problems and wrote with frankness and courage. This made him a very different kind of author.

Sigmund Freud | D.H. Lawrence

I know that William Faulkner was a great model for you. In fact, you have referred to Faulkner as the first writer you read with pen in hand, analyzing his narrative techniques. From what you’ve said, it appears that Lawrence was not that type of writer for you.

No, Lawrence was not a model for my writing; I never read him with pen in hand. His narrative technique was conventional and he was not very innovative, although his language was quite interesting.

Nevertheless, are there any points of contact between these two writers, who were contemporaries?

Lawrence was not unlike Faulkner in his reaction against intellectualism. Both felt that intellectualism killed life and pleasure, that it took away from a rich and fruitful life. They both stressed the idea that theory and intellectualism suppressed spontaneity, which is the life-giving force.

D.H. Lawrence (passport photo, 1919) | William Faulkner (passport photo, 1960)

Where would you place Lawrence in light of two other central writers of his time, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf?

Lawrence’s work is very unequal. He wrote some disastrous things, like The Plumed Serpent and Kangaroo, while everything that Woolf wrote, for instance, is interesting. And Joyce was nothing less than a genius. So, I would have to say that Lawrence is less important. Also, while one is struck by the formalistic innovation of Woolf and Joyce, Lawrence’s work, as I’ve said, is more conventional. But Lawrence stands out because of his messianic attitude as a prophet of a new religion, a religion of sex, pleasure, and nature.

James Joyce, 1937 (Photo: Josef Breitenbach) | Virginia Woolf, 1902 (Photo: George Charles Beresford)

Yes, there is certainly a good bit of sex in Lawrence’s fiction. He had problems with the censors in his time, and even today one is struck by the erotic nature of his work. As critics, we cerebral types often consider sex in fiction at best an example of other conflicts or themes in the work; at worst cheap pornography. What important role does sex play in Lawrence’s work, your work, or in fiction in general?

Sexual experience is a central part of life and for an artist to ignore that is inappropriate. Especially the novel, as total representation, should not ignore the sexual, the sensual, and the erotic. It is only if these elements completely dominate a work that their use becomes mechanical and something resembling pornography.

But where can one draw the line between the sexual-sensual- erotic work and the pornographic work?

The line between these limits is fine; it is a formal matter. If the structure of a work treats these matters with sensibility and a formal acumen, then that work transcends pornography. While the sex in Lawrence is prudent and orthodox, as opposed to the baroque and torturous sex in Faulkner, it is often hyperbolic. This caused problems. But it was not gratuitous sex: it was expressed very beautifully, with a stylistic excellence not found in pornography.

William Faulkner, 1956 (Photo: Richard Crowder) | D.H. Lawrence, 1915 (Photo: Elliott & Fry)

So how would you explain Lawrence’s problems with the censors?

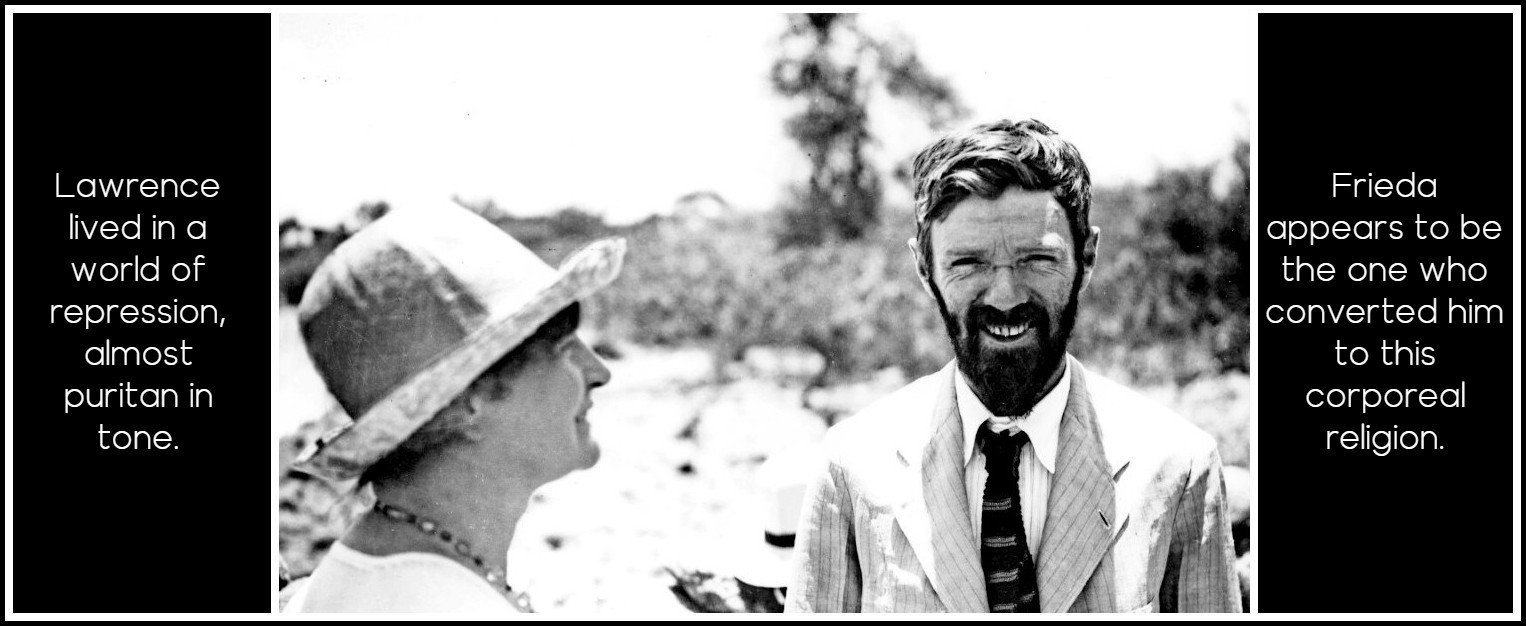

Lawrence lived in a world of repression, almost puritan in tone. And Lawrence, in some sense, expressed the religion of the body, a revolutionary and courageous stance to take in his time. Frieda, his second wife, appears to be the one who converted Lawrence to this corporeal religion.

As we talk about the sensual and erotic nature of Lawrence’s fiction, I cannot help but think of In Praise of the Stepmother, which has been described by some as an erotic novel. How did you conceive this work?

The original idea was to create a book with the Peruvian painter Fernando Szyszlo: I was going to write the text and he was going to do the illustrations. Originally, we conceived of this as a joint project. Unfortunately, we were never able to coordinate our ideas on this book, although the concept of relating paintings and fiction continued to intrigue me. That is why the language is so visual and descriptive. For the first time, I did use langage précieux. In other words, the language in this novel is not so transparent; rather, it is a presence by itself.

So meditating on these paintings, which are actually reproduced in the text, helped you construct a pictorial language?

Well, the fact of the matter is that I did not write this novel while looking at the paintings, but rather used paintings that were already in my memory, residing there for whatever reason. They must have been important to me or I would have forgotten them. I used my memory to fantasize rather than to meditate. I wasn’t trying to be accurate; instead, I tried to improvise freely.

Frieda and D.H. Lawrence in Mexico, 1923 | Photo: University of Nottingham

Another outstanding aspect of Lawrence’s work is his dedication to the novel as a supreme form of art. In some of his critical works he points out that the novel is the best way to avoid absolutes. He writes, ‘The novel is the highest form of human expression so far attained. Why? Because it is so incapable of the absolute.’ Likewise many of your novels have been dedicated, in part, to exposing the hypocrisies and the dangers of fanaticism. Is the novel the most appropriate genre to express this interest in non-absolutes?

The novel is a literary genre which needs to express the relationship of people among people. While poetry is an expression of the individual, the novel is never solipsistic. Rather, it deals with human relations. To write a novel you need this kind of pluralistic vision of problems and attitudes. The novel is related to history and social issues; it isa genre which can absorb other genres, like poetry and theater. It is an ambitious process. But the novel, in order to succeed, cannot be exclusively concerned with history. It is an artistic form and must add something to the living world. That is the ambiguity of the novel: if it deals only with the past, it is a failed novel, for it must be the creation of something new. It must be the product of fantasy, imagination, and obsessions. The great novelists integrate history and social experience with a new and totally inventive element.

Mario Vargas Llosa

What is your favorite novel by Lawrence?

The Rainbow stands out as the best in my memory. It is a rich novel, full of diversity. Sons and Lovers is another great work. The Plumed Serpent was his worst, and even Lady Chatterley’s Lover was somewhat of a failure because it is a bit naive, focusing on a revival of pagan desires in middle-class English society. The pagan love scenes are a bit ridiculous, even though they include some powerful images. But in all of Lawrence’s work, without having to agree with him, you can judge him with sympathy.

In your readings, what is the source of this sympathy?

It is obvious that Lawrence had a fear of industrial society which he felt could destroy some of the most valuable aspects of humanity. Therefore, he focused on the natural man. You could say that Lawrence was a reactionary, but his revelation of the dehumanizing process has been justified by what is happening today in the world. You could actually do an ecological reading of Lawrence without any problems. Another essential aspect of Lawrence’s philosophy is his desire to understand and see different cultures. And even though many of these projects failed, you can still safely say that Lawrence was not ethnocentric.

D.H. Lawrence, 1915 | Photo: Elliott & Fry

Now that you have seen the D.H. Lawrence ranch, what are your impressions?

It’s a very beautiful place. I can see how Lawrence would have liked it very much. For a man who was fascinated and impressed by natural forces, this place is perfect. Lawrence had a passion for the preindustrial world: he saw in what some consider progress a force transforming man into machine. Ah, but here in this beautiful setting, under this immense sky, you can feel the natural forces which Lawrence found more interesting and more humanizing.

D.H. Lawrence, Witter Bynner, Frieda Lawrence | Teotihuacán, 1923

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments