Sprague’s Acrostic Poems

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

All poems © 2017 Richard Jonathan. All rights reserved.

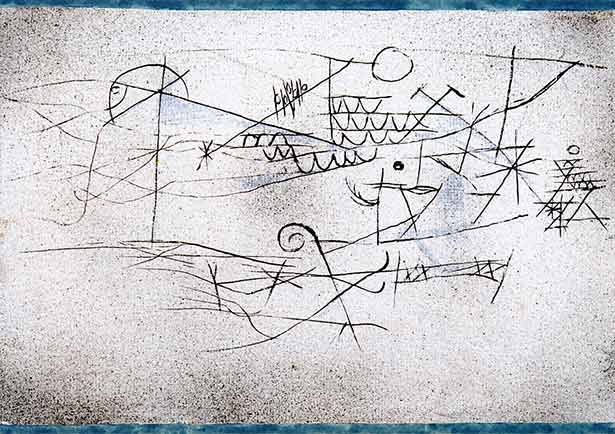

Paul Klee, Wintery (Scenic Abstract), 1923

A Change of Perspective

A gentle breeze or a great storm?

Concord, submission, reverence and love:

His kisses are none of the above. What then?

Artfully, his kisses take me to where I know

Not who I am. He,

Graceful and savage, makes me

Ecstatic, in a space of pure letting-go.

Onward and onward,

Falcon on the wing, onward.

Perhaps

Everything

Repeats:

Sex constantly repeats the first time.

Perhaps

Everything, to be itself, must

Combine with its opposite:

The beginning with the consummation.

Impossible aspiration,

Vexing question: Am I only

Everything I am not?

An Attempt at Silence

Abeyance, the fall of a snowflake;

New-minted world, virgin.

A face in a mirror,

The slither of a serpent,

The flow of sand in an hourglass.

Erasure, interstice, absence.

Moth’s wing, soft smoothness;

Petals falling from a dry stem,

The floating of a feather.

Alabaster, an egg in moonlight;

Talcum under a wedding dress.

Shrouded furniture,

Islands from the air;

Lovemaking while children wakeful.

Ellipsis, interval, caesura.

Night summoning nakedness,

Communion wafer;

Eternity, stars.

Quietude

Quiver, the discarded tail of a lizard.

Uninhabited here, as far as the eye can see.

Immemorial stones under endless sky,

Eerie.

Thewless vegetation,

Uncompassed fields.

Dark vessel,

Emptiness.

Pause

Pathways of desire elude sextant,

Abacus, gnomon, and compass;

Unencumbered,

Skeins of nerves

Earth the aerial.

A Moment of Stillness

A skeleton of leaf, scorched and charred.

Mystery, where the light nests.

Only, ever, always

Mourning, thickening the darkness.

Eclipse,

Negation;

The residue of a life.

Obliterated spoors, husks of needs:

Forgotten.

Serried rows of spectators,

The public burning of a heretic.

Incessant downfall,

Landslip, scree, stones—

Lapidary torture.

Nexus of scarecrows.

Exclusion,

Surcease; no

Spital-house bed, but deliverance.

Child-Woman

Contemplative ecstasy,

Humbly seeking enlightenment

In the sun:

Lizard, where do I come from?

Dream-work, night-times of dream-work.

Warden of the dark house,

Of what must I be aware? Speak, owl.

Milk binds

And restores, but not the milk of nightmares:

Nothing living is free of a shadow.

Interval

Innocence, purity and secrecy,

Nostalgia for the odour of chastity:

The pearl coming to birth in the oyster

Entangles the spirit in the flesh. Hark!

Reverberation of the bell—

Visitation of the plague,

Awful, sublime, precious—

Leeched, my blood becomes flowers and metals.

Isolation

Inside a lupine rosette, a snowflake.

Saxifrage spreads a cloth of gold,

Orchids defy ice.

Look! Lichen-freckled boulders shelter fossils.

And now a new solitude overcomes you:

Trauma freezes time,

Irradiating absence with unknowing;

Only desire moves, refusing to concede

Never can two be one.