The Creative Use of Constraint

TENSE IN FICTION: NARRATIVE MODE VS. SPEECH MODE

Christine Brooke-Rose

Abbreviated from Christine Brooke-Rose, ‘The Author Is Dead, Long Live the Author’ in Christine Brooke-Rose, Invisible Author: Last Essays (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2002) pp. 130-155. Slightly edited, with rare emendations, for readability.

Christine Brooke-Rose, 1964 | Photo: Mark Gerson

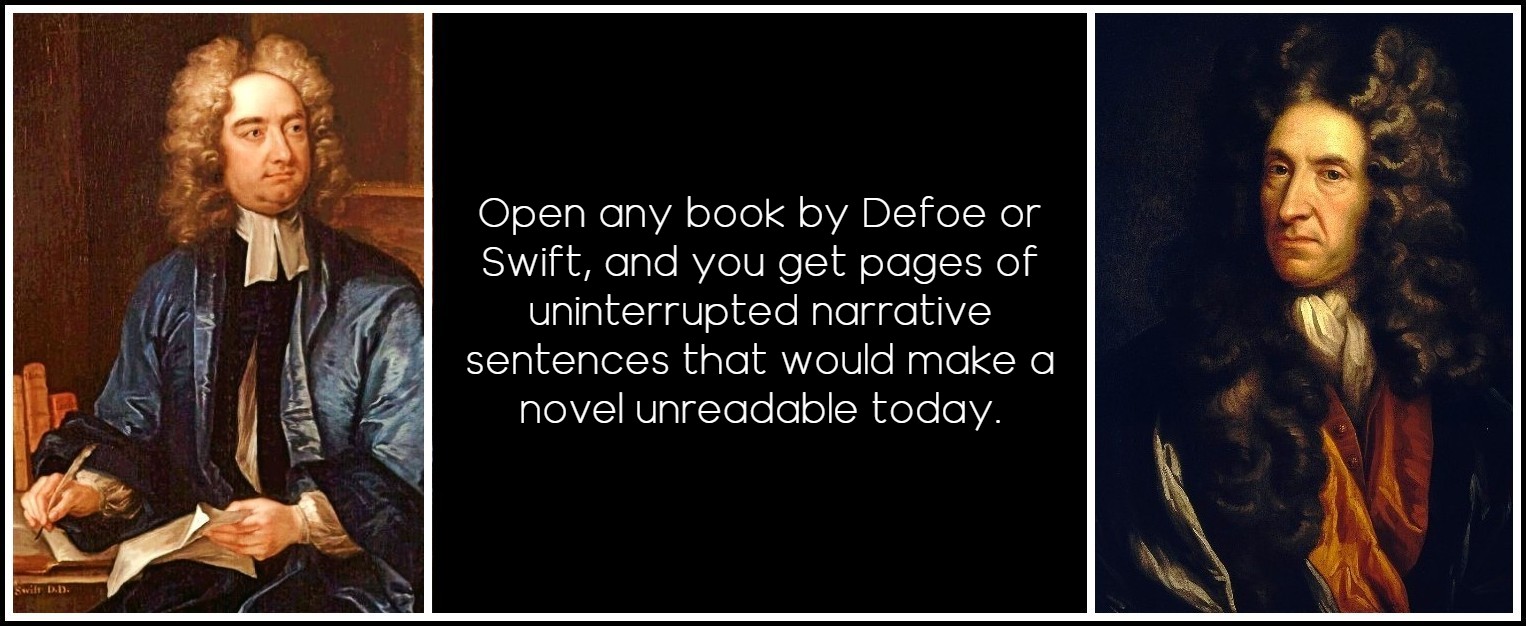

The twentieth century began with a growing resentment of the author’s guiding presence in every sentence, the enveloping of every fact with comment. Authorial guidance was given in narrative sentences, as opposed to speech or thought by characters: narrative mode versus speech mode, each with a different grammar. We tend to forget that epic and romance and the early modern novel consisted overwhelmingly of narrative sentences and little dialogue, a preference for telling over showing. Open any book by Defoe or Swift, and you get pages of uninterrupted narrative sentences that would make a novel unreadable today. With Sterne and Fielding we get more speech forms, not only from characters but in playful author addresses to the reader. Then with Jane Austen dialogue elegantly enters, but it develops slowly. Her characters are fixed psychologically and socially through speech. With Henry James comes the claimed preference for showing over telling, but in fact the narrative sentence, more and more complex, still largely dominates.

Jonathan Swift (Painting: Charles Jervas, 1718) | Daniel Defoe (Painting: Godfrey Kneller, 17th-18th c.)

The novel has been making a huge effort to shake off the authoritarianism of the traditional narrative mode. At first, one solution was to take even the narrative sentences right inside the character as free indirect discourse; another was to get away from that and allow far more direct speech mode, either inside the character (interior monologue, as in Joyce) or as dialogue with outside viewpoint but no comment (as in the ‘anti-Modernists’ Hemingway or Waugh, as opposed to James or Woolf). An extreme version of that was the novel wholly or almost wholly in dialogue (as in examples by Henry Green or Ivy Compton-Burnett), but this, as Nathalie Sarraute later commented, was pushing the novel into the theater, where it is bound to be inferior. However, some indication of who was speaking, and how, was thought minimally necessary, and continued late. For example, in 1963 in Iris Murdoch’s The Unicorn: ‘She thought, her heart sinking a little’. These parentheticals, as linguists call them, and their desperate variants, already parodied by Joyce in Ulysses, were later attacked by Sarraute as ‘symbols of the old régime’.

Iris Murdoch, The Unicorn, 1963

But parentheticals and narrative comment are only one type of author intrusion, and easily jettisoned. They had already vanished in Tarr by Wyndham Lewis (1918), but kept recurring. Peter Ackroyd, for instance, was still parodying them with italics in Hawksmoor (1985), but soon suppressed them. Another easily jettisoned guidance is in chapter headings, fulsome in the nineteenth century, then dropped, now more discreetly reappearing.

Wyndham Lewis, Tarr, 1918 | Peter Ackroyd, Hawksmoor, 1985

A much more pervasive feature was the past tense, which has always been used as reassuring guarantor of real events. In 1953 Alain Robbe-Grillet used the present tense throughout in Les Gommes, as did Beckett in Molloy and Sarraute in Le Planétarium. Their uses of the tense are, however, very different from each other, and had been partly foreshadowed by others. By 1963, in Pour un nouveau roman, Robbe-Grillet was naming the use of the past tense as the distinguishing mark of the traditional novel. The French narrative tense, the aorist or passé simple (passé défini) started dying in the seventeenth century and is now, being purely literary and never used in speech, fully dead, unlike the past in English or other languages, where the gap between literary and spoken language is less extreme.

Samuel Beckett, Molly, 1951/55 | Nathalie Sarraute, Le Planétarium, 1959 | Alain Robbe-Grillet, Les Gommes, 1953

There had been many attempts to get free of this past tense narrative sentence. In nineteenth-century fiction, brief passages in the historic present are used for vivid descriptive non-action scenes before safe return to the past; and the present tense is favored for universalizing moral or social comments from the author. Or, much easier, the handing over of narrative to a character inside the story who, unlike Robinson Crusoe and other early I-narrators, are allowed to pass from the classic narrative sentence to the present and other tenses of speech mode. Already Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground (1864) is a non-stop monologue by the hero. So are diary forms, and, earlier, epistolary forms (still predominantly in narrative mode, however). And, of course, the varyingly rhythmed (chopped, telegraphic, unpunctuated) interior monologues of Stephen, Bloom, and Molly in Ulysses (1922). As a narrative tense, however, the present was first experimented in 1874 by Flaubert in La Tentation de Saint Antoine and in 1887 by Edouard Dujardin in Les lauriers sont coupés, then by Joyce, first very occasionally as historic presents for sudden vigor in Ulysses, then coming into its own in Finnegans Wake (but here Joyce purposely blurs the very distinction I am talking about).

Edouard Dujardin, Les lauriers sont coupés, 1887 | Flaubert, La Tentation de Saint Antoine, 1874

Tense didn’t really become a narrative issue till the 1950s. Beckett’s earlier novels were in the past tense, as was Sarraute’s earlier work. Camus’s L’étranger, written in the present perfect (passé composé) of speech mode, with its famous first sentence, ‘Aujourd’hui, maman est morte,’ appeared in 1942. And 1932 saw the publication of Louis Ferdinand Céline’s Voyage au bout de la nuit, written in an ultra-colloquial French, that is to say in speech mode, a mixture of present perfect, present, imperfect, but also, still, aorist. That went unanalyzed at the time, perhaps because the amount of dialogue masks the narrative sentences, all however pronounced in the first person of speech mode. The astonishment L’étranger caused in France, however, was at an I-narrator so empty, so—as Robbe-Grillet put it—‘absent from himself’. Tense was not properly discussed.

Albert Camus, 1954 (Photo: Yousuf Karsh) | Albert Camus, L’étranger, 1942

Proust’s frequent présents d’écriture (‘j’entends la rumeur des distances traversées’) were not dealt with until Genette on ‘Voice’ and ‘Narrative Instance’ in 1972, and strictly speaking are author interference in speech mode rather than narrative. His famous first sentence in the present perfect, ‘Longtemps je me suis couché de bonne heure,’ had after all appeared in 1913, even if it wasn’t really analyzed as tense until Serge Doubrovsky devoted a whole article to just that in 1971. But Proust at once continues his narrative, more traditionally, in the imperfect (continuous past, ‘mes yeux se fermaient’), so well used by Flaubert as ideal solution to the dying aorist, whereas Camus’s entire short narrative is in the present perfect. The narrator’s ‘absence from himself’ has in fact little to do with tense; it is achieved through the I-narrator necessary to speech mode describing only outside events, never himself or his reactions.

Marcel Proust (Painting: Jacques-Émile Blanche, 1892)

In 1966, a structuralist linguist, Emile Benveniste, clarified the distinction between histoire and discours (‘history’ and ‘speech’). So as not to create confusion with Genette’s later use of discours for ‘treatment’ and récit for ‘story,’ from the Russian Formalist fabula and syuzhet (the what and the how, the raw material of a story and the way a story is organized), I have here preferred ‘speech’ versus ‘narrative’. Benveniste’s distinction is entirely about the how, two types of telling, one for history, which uses a particular type of impersonal sentence to tell of events, and the other for the speech system (addressing the reader or, in the novel as in life, characters and people addressing each other). Here is Benveniste on the narrative sentence used for history: ‘Nobody speaks here, events seem to narrate themselves. The fundamental tense is the aorist, which is the time of events outside the person of a narrator’. If the aorist really expresses ‘the time of events outside the person of a narrator,’ this would explain the death of the once imposed passé simple in speech—and a possible difference of attitude in English and other languages, where the past tense can and does also belong to the speech system. There is no dead aorist.

Benveniste, Problèmes de linguistique générale 1 & 2, Tel Gallimard

The main point here, however, is that the ‘historical’ past tense is speakerless, and—as historical narrative also ignores audience—it is not only speakerless but addressee-less. In other words, the narrative sentence of historical narrative is outside the personal speech system and cannot use its tenses. Nor can it use its deictics: it has to say ‘then’ for ‘now,’ ‘there’ for ‘here,’ ‘the next day’ for ‘tomorrow,’ ‘the day before’ for ‘yesterday,’ ‘the following year’ for ‘next year,’ and so on; it should even avoid deictic verbs, which situate the speaker in space (e.g., ‘came’ versus ‘went’). The tenses of speech mode are the present, the present perfect, and the future. The French imperfect, which in English is the past progressive (was going) or iterative (would [often] go), seems to belong to both historical narrative and the personal speech system. Hence Proust could use the imperfect for the dead aorist throughout his long narrative without causing much shock or even notice. In English, as the past tense is also part of the speech system, there is no dead aorist, as already noted.

Émile Benveniste

It may seem contradictory to talk of a revolt against author intrusions and at the same time to cite a structuralist’s dictum that in the narrative sentence ‘no one speaks.’ It isn’t really. Benveniste is talking about the historian’s sentence, and one of the sources of the modern novel is the chronicle. But the struggle to ‘speak’ despite the speakerless sentence started early, with first-person narratives (as in Defoe and Swift) or author interference in the first person (Fielding, Sterne), or in varyingly fulsome chapter headings (Fielding, Dickens, Trollope; epigraphs in Kipling); or by imposing a ‘personal’ style (for example, more lyrical or opulent) on the ‘impersonal’ and distancing past narrative sentence (Thackeray, Meredith) or a complex one (Henry James).

Henry James, 1884 | Photo: Elliott & Fry

By the 1930s the author’s control was felt as omniscient and godlike. It was felt in the use of the distancing past tense and its distancing deictics, in the distancing third person even when plunged inside a consciousness (James or Woolf); it was felt even in the outside viewpoint with minimum comment and more dialogue, not only with the parentheticals that went with dialogue, but also in indirect discourse, which is a summary of what a character actually said, as well as in free indirect discourse, which I’ll come to in a moment. The last two devices (indirect discourse and free indirect discourse) vanished, more or less, in the nouveau roman, with its brand-new, startling present tense and its equally startling variations. It is not the use of the present tense as such that is original, but how it is used. Let us take four examples from the fifties (in order of ‘newness’ rather than date):

1. BECKETT, MOLLOY (1950/55) OPENING:

I am in my mother’s room. It’s I who live there now; don’t know how I got there.

2. DURAS, LE SQUARE (1955) OPENING:

L’enfant arriva tranquillement du fond du square et se planta devant la jeune fille.

‘J’ai faim,’ déclara-t-il.

Ce fut pour l’homme l’occasion d’engager la conversation.

‘C’est vrai que c’est l’heure de goûter,’ dit-il.

La jeune fille ne se formalisa pas. Au contraire, elle lui adressa un sourire de sympathie.

Marguerite Duras, Le square, 1955

3. SARRAUTE, LE PLANÉTARIUM (1959) OPENING:

Non vraiment, on aurait beau chercher, on ne pourrait rien trouver à redire, c’est parfait… une vraie surprise, une chance… Une merveille contre ce mur beige aux reflets dorés…

4. ROBBE-GRILLET, LES GOMMES (1953) OPENING:

Dans la pénombre de la salle de café le patron dispose les tables et les chaises, les cendriers, les siphons d’eau gazeuse; il est six heures du matin.

Il n’a pas besoin de voir clair, il ne sait même pas ce qu’il fait. […] Bientôt malheureusement le temps ne sera plus le maître. Enveloppés de leur cerne d’erreur et de doute, les événements de cette journée, si minimes qu’ils puissent être, vont dans quelques instants commencer leur besogne. […] Mais il est encore trop tôt. […] l’unique personnage présent en scène n’a pas encore recouvré son existence propre.

Beckett, in this particular matter of tense, has dropped the past narrative sentence for the conventional ‘pronouned’ speech form, as in, say, Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground or Céline’s Voyage au bout de la nuit. This is the only ‘legitimate’ use of the term ‘narrator’. Duras is still using the traditional past tense narrative sentence to introduce the man and girl, but once the child is gone, taking with him the quotation marks and the parentheticals, the rest is in dialogue (designated with mere dashes), therefore in conventional speech forms. Duras, in other words, still uses the convention of past tense for narrative. But she will soon adopt the present tense, if not always dropping the parentheticals but emphasizing them, for example, in La Maladie de la mort (1982): Et puis elle demande: Vous voulez quoi? Vous dites que vous voulez essayer [indirect speech for several lines]. Elle demande: Essayer quoi? Vous dites: D’aimer. And in most of her later novels the present tense is used vividly, dramatically, to increase the emotion, and sometimes omnisciently.

Céline, Voyage au bout de la nuit, 1932 | Dostoyevsky, Notes from Underground, 1864

With Sarraute, we are plunged into speech forms (in various tenses) but inside the consciousness of someone. As in Robbe-Grillet we do not know whose mind we are in, there is no je (in the opening), but (as in James or Woolf) that mind is represented by the third person (elle fait un grand effort, elle capte, elle tire), getting more and more excited, gushing internally, but not narrating. Robbe-Grillet, however, uses the present tense of speech form throughout the novel, paradoxically to replace its antagonist, the authoritative but speakerless omniscient past narrative sentence. In this he has been much imitated, but he will add two further paradoxes in subsequent novels. Here, however, he is giving the supposedly speakerless speaker the same omniscience as the traditional author, in both present and future. These differences, then, in these early examples, may be gropings against the authorial authority, difficult to jettison, still there. But each will develop in various and specific ways. Here I am only concerned with Robbe-Grillet and his paradoxical use of the present tense to replace the past tense narrative sentence. His second novel, Le Voyeur, makes an interesting alternation of past tenses (passé simple and imperfect) for ‘real’ events and the present tense for ‘unreal’ ones, namely fantasies (as had Flaubert for St. Anthony’s temptations).

Alain Robbe-Grillet, Martinique, 1950 | Alain Robbe-Grillet, Le Voyeur, 1955

With La Jalousie he will go further than Camus or his own contemporaries in two respects. First, and paradoxically, by using the present tense of the speech system and its deictics, but with all the impersonal speakerless tone of the past-tense narrative sentence. That is, not just for momentary vividness as in the historic present; nor in direct address to the reader, like Sterne or Fielding; nor as a playful ‘look-at-me,’ like the Postmoderns; nor as inner speech or sous-conversations, like Sarraute; nor even with occasional omniscience, as here. Rather, he uses the present tense as a ‘scientific’ present tense. This is clearly derived from cinema. Robbe-Grillet was originally an engineer and must have felt the similarity between the speakerless past-tense narrative sentence and the scientific use of the present tense. Since the traditional narrative sentence had become less and less impersonal and speakerless, he must have decided to replace it with a speakerless, ‘scientific’ present. He simply puts down objectively and in detail all that hits his central consciousness (‘protagonist’).

Alain Robbe-Grillet, 1961 | Photo: Catherine R-G

In the second paradox, Robbe-Grillet limits this new present-tense narrative sentence to one conscience, unlike the traditional past-tense narrative sentence, which is far freer to go where it pleases. It is like a scientific sentence limited to one result at the time of utterance, yet—and this is his great subtlety—constantly varied with other possibilities, even at times, corrections. The regard evokes a detective rather than a scientist: To the right, a simple shape, more blurred, already covered by several days’ deposit, is nevertheless still discernible; at a certain angle it acquires sufficient clarity for its outline to be followed without too much difficulty. It is a kind of cross: an elongated main shape, like a table knife but wider (La Jalousie, tr. Richard Howard).

Alain Robbe-Grillet, 1961 | Photo: Catherine R-G

The third paradox is that he never evokes an act of seeing or a consciousness, that is, there is no seer, only the seen, no énonciation (‘I was convinced,’ ‘surely,’ ‘it seemed,’ etc.), only énoncé. This is why I used the phrase ‘all that hits his central consciousness’ above, rather than ‘all that his central consciousness observes.’ There is no act of observation. Moreover, he dispenses with the first or third or indeed any personal pronoun normally attached to the present tense, just as science can. For instance, in La Jalousie, we never know who the jealous person is whose objectivized registrations we follow: ‘She takes a few steps into the room, goes over to the heavy chest and opens its top drawer. She shifts the papers in the rear of the drawer, leans over and, in order to see the rear of the drawer better, pulls it a little further out of the chest.’ Such a text can give two readings of the jealous character: as an observer of detached, scientific objectivity, or as an obsessed character, the latter chiefly because of the detail.

Alain Robbe-Grillet, 1987 | Photo: Catherine R-G

Genette mentions this double reading, which he tells us derives from the emphasis laid either on the story or on the narrative discourse: if emphasis is on the discourse, as in the interior monologue, the story seems just a pretext and can disappear; if it is on the story, it’s the narrative instance that tends to disappear. Genette gives La Jalousie as an extreme example, but does not mention either the absence of the first person, which effaces the looker, or the paradoxical ‘scientific,’ non-speech mode use of the present tense for narrative sentences. Either way we are there, inside the looker, feeling both what is described and a non-evoked, non-represented reaction. This comes from the astonishing use of the narrative sentence, in which ‘no one speaks,’ but used in the present tense, in which someone necessarily speaks, yet we don’t know who, since he never says ‘I’ or anything about himself. He is the very ‘no one speaks’ of the narrative sentence. We have to construct him, not even from what he says, as in most novels, but from what he sees.

Alain Robbe-Grillet | Photo: Catherine R-G

This startling change of narrative technique may well have been foreshadowed in French by Proust, Céline, Camus, and Beckett, but not in that paradoxical mix (the present tense used in narrative sentences in which no one speaks). All four use the present tense with its conventional first-person pronoun, so that we’re wholly in speech mode. Flaubert comes the closest to using the present tense as narrative sentence, yet he reserves it for hallucinations. Sarraute uses it as a ‘silent’ speech form rather than as narrative sentence, expanding her sous-conversations through more and more emotion and ending up (as she had said of novels in dialogue) in the theater. Duras too, who also made films and wrote scenarios, uses it as a narrative sentence, as does Robbe-Grillet, but a narrative sentence emotively as highly charged as Sarraute’s inner dialogue. Indeed, in Sarraute’s later novels we hear our old friend the omniscient author telling us things the character can’t know (such as ‘she can’t hear’), but they are told in the present tense, which thus seems used for greater immediacy and emotivity, rather than for ‘scientific’ objectivity. Only Robbe-Grillett, in La Jalousie, has fully achieved a form that I shall call the scientific present tense.

Alain Robbe-Grillet in Japan | Alain Robbe-Grillet, Jealousy, tr. Richard Howard

As for Joyce, the supposed father of it all, he is a special case of the diametrical opposite. In Ulysses, Joyce still uses the past narrative sentence for all activity or event whenever he’s not reproducing a character’s thoughts, which are in speech mode. But he does seem very aware of the problems posed by both narrative and speech modes, for he visibly avoids pronouns in the telegraphic speech mode of Stephen’s and Bloom’s interior monologues, so that a sudden ‘I’ is all the more visible. He turns to other genres in order to use the present ‘allowably’ as narrative; for example, the question-and-answer form of ‘Ithaca,’ which allows (inconsistently) pronounless answers, and the dramatic form of ‘Circe’ with its long or short stage directions in italics, in (inconsistently) pronounless present tenses (‘looks behind’ ) or participles (‘shuddering,’ ‘shrinking’) or adverbials (‘hurriedly,’ ‘in an oatmeal sporting suit’), through which all the character mutations are achieved.

James Joyce, Ulysses, 1922

But already in ‘Sirens’ the whole classic question of who speaks is being blurred, as if Joyce were already practicing for Finnegans Wake. Here, Bloom’s thought, for instance, includes a phrase of Stephen’s from a scene Bloom did not attend. By Finnegans Wake Joyce is intent on creating an infinitely changing speaker to replace both the authoritative narrative sentence and the socio-psychologically differentiating speech forms of the classic novel. Thus endless speakers change into each other to tell of events, ‘tales within wheels,’ in both narrative forms (for events) and speech forms (for apostrophe, insult, etc.), both in a constantly reinvented idiolect, or private language. Who speaks becomes intentionally blurred by that drowning stream of ‘punsciousness’ which, however enchanting or repelling, ingenious or infantile, enriching or irritating, cannot avoid a ‘look-at-me’ tone. An epic voice, perhaps, of Shem the Penman, though constantly escaping; the too idiosyncratic voice, in fact, of the author, very visibly ‘doing his stuff.’ The narrative sentence, then, is too richly rhetorical to be in any way assimilated, either into the traditional speakerless past-tense narrative sentence it successfully destroys, or to the impersonal scientific present tense of Robbe-Grillet. Indeed, both Joyce’s narrative sentences and speech forms together constitute its exact opposite. To Joyce, the author was still God, or at least self-fathering.

James Joyce by Wyndham Lewis, 1920 | James Joyce by César Abin, 1932

It was, I believe, Robbe-Grillet’s triple paradoxical mix in his use of the narrative sentence (an impersonal present tense, yet speakerless, yet single-visioned) that led Barthes to announce the death of the author. Of course Barthes was referring not to the real author, who has toothache and marital troubles, but to a critical construct. At any rate, the word ‘author,’ even as a critical construct, became taboo. So critics, surprisingly docile about dogmatic decrees, all started using the word ‘narrator’ instead, and I hope I have distinguished clearly enough the author’s narrative sentence from his speech forms to make the term ‘narrator’ sound truly redundant, for it blurs important narrative instances. Indeed, the word ‘narrator’ now designates anything from a first-person hero to a fictional observer-character who can be very varyingly present and very varyingly reliable, to a mere substitute where traditional criticism had said ‘author,’ or used the author’s name. Joyce’s purposeful fusion, through idiolect, would never have sunk to that level of confusion; indeed, all his extra-textual pronouncements show that he knew exactly what he was doing. The author also narrates, in case anyone had forgotten; he is the teller, that is, uses narrative sentences. He always has. But these were by definition impersonal. Yet even when remaining impersonal and unstylized, an occasional stray ‘I’ in nineteenth-century omniscient author-type novels betrays the tension.

Roland Barthes | Photo: Ulf Andersen

This classic question of who speaks led to a strange dispute, during the seventies and eighties, between certain linguists, notably Ann Banfield, and a few literary critics who held on to the traditional view that there are two voices in free indirect discourse and were quite unable to give up author intrusion, so merely changed the critical word ‘author’ to ‘narrator’. Free indirect speech, the paradoxical intrusion of expressive elements from direct discourse (speech) into a past narrative sentence, is unique to modern fiction. It was invented in the eighteenth century [Goethe, Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, 1795; a proto-free indirect speech], developed brilliantly by Jane Austen, and culminated in E. M. Forster, Flaubert, Woolf. It can even be part of a dialogue. Here are two typical examples from E. M. Forster’s A Room with a View:

Example 1: A conversation then ensued, not on unfamiliar lines. Miss Bartlett was, after all, a wee bit tired, and thought they had better spend the morning settling in; unless Lucy would rather like to go out? Lucy would rather like to go out, as it was her first day in Florence, but, of course, she could go alone. Miss Bartlett would not allow this. Of course she would accompany Lucy everywhere. Oh, certainly not; Lucy would stop with her cousin. Oh no! that would never do! Oh yes!

E.M. Forster, 1938 | Photo: Howard Coster

Example 2: Of course Miss Bartlett accepted. And equally of course, she felt sure that she would prove a nuisance, and begged to be given an inferior room—something with no view, anything. Her love to Lucy.

In the first quotation, Miss Bartlett and Lucy are in Florence; the conversation is rehearsed, perhaps ironically, either during or after, in Lucy’s mind (this would be Banfield’s theory) or by a narrator (as in the two-voiced theory). In the second quotation, it is not immediately obvious whose consciousness we are in, but when we read on we are more clearly in Lucy’s mind, Lucy echoing Miss Bartlett’s style in her head later, or while having the letter read to her by Mrs. Honeychurch. Both examples are good cases for the two-voiced theory of ‘narrator’ irony, and this is what Banfield’s book argues strongly against. According to her theory we are always in a character’s mind, either in reflective consciousness or in unreflective consciousness (the stating of the names illustrates unreflective consciousness).

E.M. Forster | Ann Banfield

Here is my own favorite example, from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Mrs. Bennett is bidding farewell to Mr. Bingley.

‘Next time you call,’ said she, ‘I hope we shall be more lucky.’ [direct discourse]

He should be particularly happy at any time, &c &c, and if she would give him leave, would take an early opportunity of waiting on them. [free indirect discourse]

‘Can you come tomorrow?’ [direct discourse]

Yes, he had no engagement at all for tomorrow [free indirect discourse]; and her invitation was accepted with alacrity. [narrativized discourse]

Such swift changes of register are frequent in Austen. But who says ‘&c &c’? The two-voiced theory supporters would hear narrator irony about polite formulas, but in Banfield’s theory (she would use linguistic argumentation), it would represent the character’s own awareness, at a non-verbalized, semi-conscious level (formulas he could add but does not, or formulas he is adding and still uttering, while thinking ‘&c &c’), but which we are not given.

Jane Austen | Ann Banfield

Much more often, however, there are no such deictics, and the sentence is formally just like a straight narrative sentence. Here is a famously ambiguous example from Jane Austen’s Emma:

He [Frank Churchill] stopped and rose again, and seemed quite embarrassed [narrative sentence]. He was more in love with her than Emma had supposed.

That last sentence reads as a narrative sentence like the first, coming from the author (or narrator in modern parlance) and therefore, by convention, is true within the fiction. But on second reading, when we know that Emma was gravely mistaken, we can only read it as Emma’s thought, in free indirect discourse.

Jane Austen, Emma, 1816

Ann Banfield has rigorously analyzed this kind of free indirect discourse, which she prefers to call ‘represented speech and thought’. I’ll do the same in this section, since the term is more accurate, not only because it can represent both speech and thought, but also because this type of sentence does not ‘imitate’ speech or thought but ‘represents’—re-presents—it. This is an important distinction. Although Banfield starts from a slightly revised version of Benveniste’s distinction between histoire and discours, her analysis is not structuralist, for she bases her argument on generative grammar. Her book is called Unspeakable Sentences (1982), because both narrative sentences (where no-one speaks) and represented-speech-and-thought sentences are specific to the narrative mode, whereas direct and indirect discourse can occur in the personal speech system. These two types of sentence, the narrative sentence and the sentence of represented speech and thought, are both speakerless, literally unspeakable, in the speech mode of the personal system.

Ann Banfield – Unspeakable Sentences and three other books

Banfield’s book is a rigorous attempt to answer the traditional view of represented speech and thought as representing two voices, that of the character and that of a so-called narrator. This view has to attribute different bits of the sentence to one or the other. She cites many literary examples given by holders of that traditional view, demolishing them one by one. For instance, we read, in Emma Bovary’s consciousness: ‘She loved the sick lamb, the sacred heart pierced with sharp thorns, or poor Jesus falling as he carries the cross.’ The traditional view has always read this kind of sentence as author/narrator irony about pious sentimentality. But for Banfield, we are inside Emma’s mind, but she is not consciously ‘saying these words’ to herself; they ‘re-present’ her vague thoughts and feelings. Banfield blames the modern silencing of the author for these various double-voiced formulations and for introducing ‘the notion of a narrator as a created persona distinct from the author alongside the notion of point of view,’ which includes evaluation. The author, she says, is ‘expunged’ but ‘reintroduced as narrator who is responsible for all the sentences in the text, as the speaker is in discourse.’ She defends an alternative theory, which sees author and narrator as distinct constructs of literary theory where ‘narrator’ is restricted to cases when the author does create a narrator, namely the first-person narrative.

Flaubert, Madame Bovary, 1857

Banfield insists that even as a construct, the author is not represented in the text but can only be inferred through interpretation. Most of Banfield’s book is devoted to syntax, but she also deals with her opponents’ semantic arguments, which posit either an ‘empathy’ of the narrator or an ironic commentary. On empathy, which is linked to ambiguous represented speech and thought sentences, she invokes a consistency criterion: the facts of the fiction must be consistent with one another. For example, the sentence about Frank Churchill being in love with Emma can’t come from an undramatized narrator, nor can the character’s value judgments. As for irony, the classic case for the dual voice theory, she insists that ‘one can argue that represented speech and thought is the main vehicle for irony without thereby implying that this is an argument for the dual-voice position. For the ironic reading of a sentence cannot be treated as part of its meaning, in any accepted sense of linguistic meaning’. The two meanings of an ambiguous sentence have exactly the same syntactic and semantic structure. With irony we are beyond grammatical or even semantic rules. The irony is provided by the reader (which is why it can also be missed). Irony is a way of reading. ‘There is nothing to which the notion “narrator’s point of view” can be semantically attached that is not equivalent to the character’s point of view’.

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, 1813

Curiously, however, Banfield makes no mention at all of Robbe-Grillet’s paradoxical attempt to use the present tense for ‘unspeakable’ narrative sentences, which are impossible in her system, nor indeed of any other writer’s much more conventional use, employing a pronoun, of present-tense narrative. Nor does she address Joyce’s represented thought in the present tense, also impossible in her system (she would call it ‘inner speech’). Her book concerns only the two traditional types of ‘unspeakable’ sentences, the narrative sentence and the sentence of represented speech and thought, both in the past tense. But she stops at Faulkner, Woolf, and Joyce. As we saw above, Forster’s use, though as witty as Austen’s, is already a little less clear as to whose mind we’re in, the character’s or the author/narrator’s. Indeed, this two-voice ambiguity is already felt in Flaubert, who was the first to develop the French imperfect to slide in and out of represented-speech-and-thought and narrative sentence: character reaction and author intrusion. By the time of Joyce this can be quite muddy. Why? Because, just as he killed the notion of fixed socio-psychological discourse for characters, Joyce killed represented speech and thought. It only occurs when he is parodying traditional styles, notably in ‘Wandering Rocks,’ ‘Scylla and Charybdis,’ ‘Cyclops,’ and ‘Nausicaa’. Joyce killed represented speech and thought (a version of author-controlled narrative sentences) by representing thought in speech mode. But not everyone read Joyce, and even the killing of represented speech and thought took a long while to trickle through.

Desmond Harmsworth, Joyce at Midnight, 1930

And during this long while, represented speech and thought, filtered through a character, came to be very lazily used as a way for the author to convey narrative information to the reader, since author intervention was by now unfashionable. It’s a stock method in early or mid-century science fiction, for instance, where a scientist is made to think technical but elementary matters: this is author intervention for the reader, of whom the scientist in this genre should not be aware. In Robbe-Grillet, of course, as in most nouveaux romans, represented speech and thought vanished together with the past tense. No two types of text, in my view, seem further apart than any novel by Robbe-Grillet and Molly Bloom’s interior monologue in ‘Penelope’ or Stephen’s in ‘Proteus’ in Ulysses. I happen to prefer Robbe-Grillet’s solution: it’s less messy. We do not reflect, or even ‘non-reflect,’ in represented speech and thought. Banfield: ‘Henry James’s complex sentences do not imitate what Maisie thought but represent what Maisie knew.’ Here the author is very much present and doing the representing. Banfield concludes: ‘The artificial nature of represented consciousness which emerges in the analysis of sentences of non-reflective consciousness can thus easily extend to represented thought. It represents a reflection but not necessarily one cast in language the character might have used’.

Henry James, What Maisie Knew, 1897

The present tense is extremely current now, though conventionally, in ‘pronouned’ narrative instance. For instance, Peter Ackroyd plays sensitively with tenses and alternating he/I pronouns in the hallucinatory last few chapters of Milton in America (1996). In fact, it crept in more and more during the eighties. It is current simply as a tense, requiring and getting a first person. Indeed, we’re flooded with first-person narratives at the moment, in both past and present tenses. But the present has not been used, to my knowledge, as new narrative sentence in speakerless, narratorless narrative (a modern version of represented speech and thought), which paradoxical use is what gives Robbe-Grillet such a distinctive tone. Even as tense, it’s often misused. Indeed, it is difficult to use as narrative tense, not only for all the grammatical reasons I have touched upon, but also for stylistic reasons: at every sentence the constraint excludes easier formulations and forces one to find an alternative. Like any constraint, the present tense is a limitation, but one that allows greater concentration on one aspect, simultaneity.

Peter Ackroyd, Milton in America, 1996 | Peter Ackroyd (Photo: Charles Hopkinson)

The present tense is also difficult to use for more generic reasons: the present is the predominant tense of lyric poetry. It is apt for lyrical description, less so for fictional action, which has for so long depended on the ‘guarantee’ of the past narrative sentence, so that the use of the present for action recalls those brief historic presents for vivid, non-action scenes in the classical novel. The present tense is also the tense of general statements and universal questions, the novelistic equivalent of ‘scientific statements,’ such as authors loved and still love to make in their intrusions, which can sound either dogmatic or banal. This is true at least in English, which, unlike French, also has the continuous present for simultaneous action and so tends to reserve the normal present tense for generalization. Consequently, young writers who think, a little behind the times, ‘Ah, the present, that’s the latest thing,’ and then merely replace the past in the traditional narrative sentence by the present, achieve, to my mind, little more than the critics who have merely replaced the word ‘author’ by the word ‘narrator’. Indeed, the present tense nowadays often reads like a mechanical replacement of the past narrative sentence, regardless of true effect. It is often reduced to mere vividness, like the historic present, and so still coddles the reader, wrapping every fact in the safety of its ‘cool’ reassurance.

Joshua Hoehne, Unsplash | JR Korpa, Unsplash

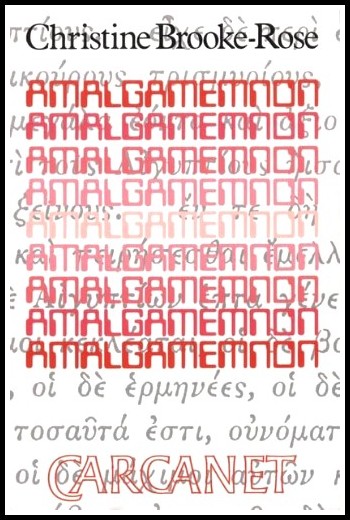

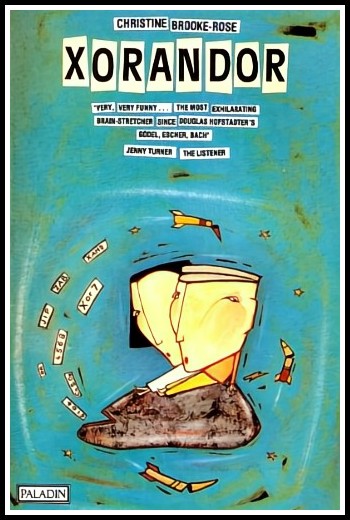

CHRISTINE BROOKE-ROSE: THREE NOVELS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE NOVEL

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments