JAMES JOYCE

Finnegans Wake

Derek Attridge on the Pormanteau in ‘Finnegans Wake’

UNPACKING THE PORTMANTEAU; OR, WHO’S AFRAID OF ‘FINNEGANS WAKE’?

Derek Attridge, Emeritus Professor at the University of York, is well-known as a Joyce scholar.

Abridged from Derek Attridge, Peculiar Language: Literature as Difference from the Renaissance to James Joyce (Cornell University Press, 1988) pp. 195-209.

That the last major work of one of the language’s most admired and influential writers—the product of some sixteen painful years’ labor—has remained on the margins of the literary tradition is an extraordinary but well-established fact. There can be no doubt that a major reason for this negative reaction is the work’s intensive use of the portmanteau word, which is what makes the style ‘outlandish,’ demands ‘effort’ from the reader, renders the work ‘laborious’ and ‘unrewarding,’ inhibits the communication of ‘felt life.’ The portmanteau word is a monster, a word that is not a word, that is not authorized by any dictionary, that holds out the worrying prospect of books which, instead of comfortingly recycling the words we know, possess the freedom endlessly to invent new ones. Sixty years after it first started appearing [now over ninety years], the novel—if the Wake can still be called a novel—that makes the portmanteau word a cornerstone of its method remains a troublesome presence in the institution of literature.

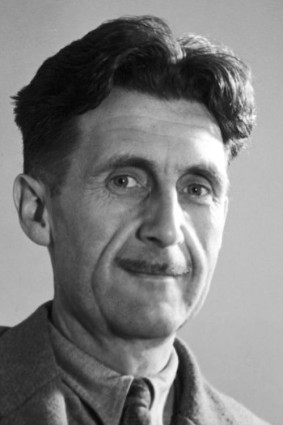

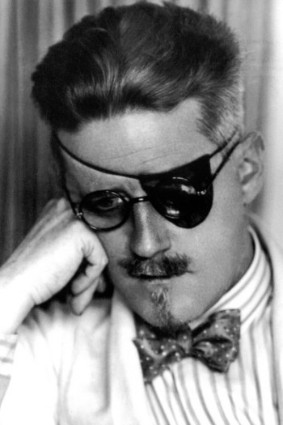

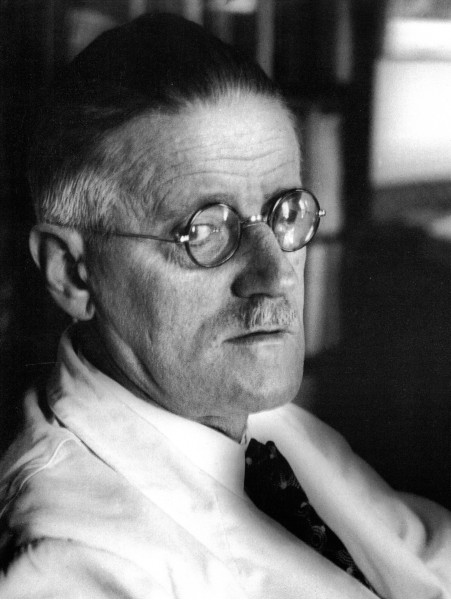

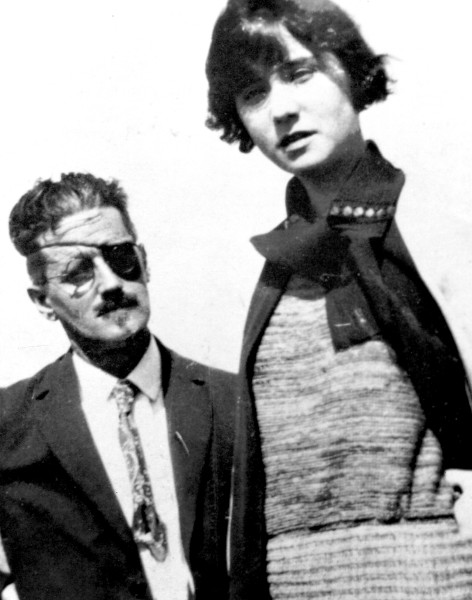

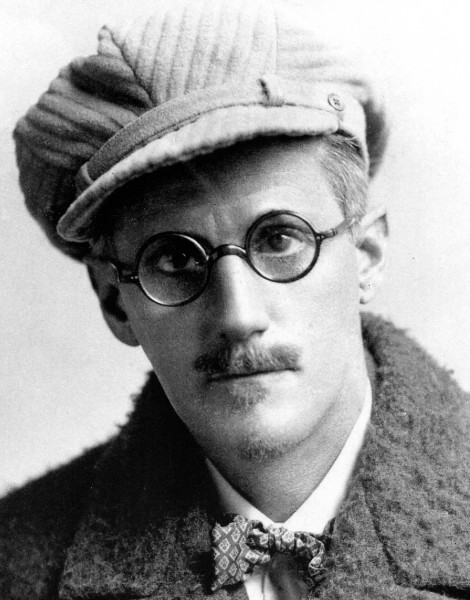

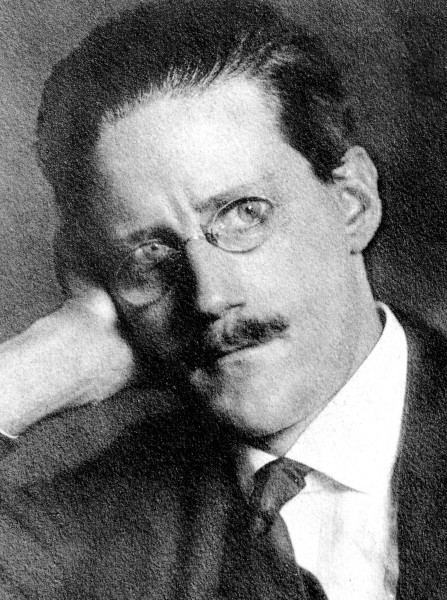

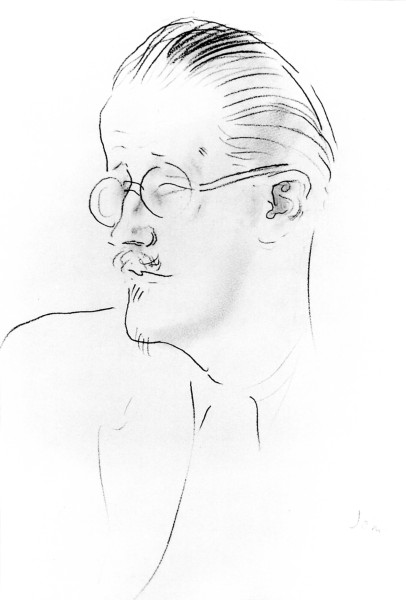

James Joyce, Paris, 1937 | Photo: Josef Breitenbach

The portmanteau word challenges two myths on which most assumptions about the efficacy of language rest. Like the pun, it denies that single words must have, on any given occasion, single meanings; and like the various devices of assonance and rhyme, it denies that the manifold patterns of similarity which occur at the level of the signifier are innocent of meaning. Not surprisingly, therefore, the portmanteau word has had a history of exclusion much more severe than that of the pun. Outside the language of dreams, parapraxes, and jokes, it has existed chiefly in the form of malapropism and nonsense verse—the language of the uneducated, the child, the idiot. (The very term ‘portmanteau word’ comes from a children’s story, Alice Through the Looking-Glass, and not a work of theory or criticism.) And the literary establishment has often relegated Finnegans Wake to the same border area. How else can it avoid the claim made by the text that the portmanteau word, far from being a sport, an eccentricity, a mistake, is a revelation of the processes upon which all language relies? How else can it exclude the possibility that the same relation obtains between Finnegans Wake and the tradition of the novel, that what appears to be a limiting case or a parody, a parasite on the healthy body of literature, is at the same time central and implicated in the way the most ‘normal’ text operates?

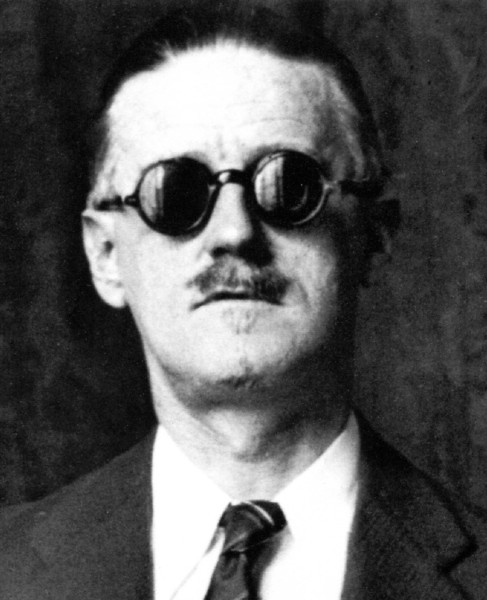

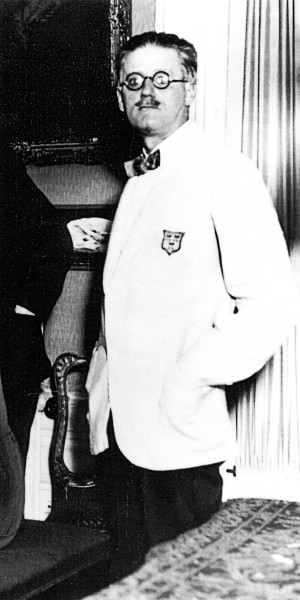

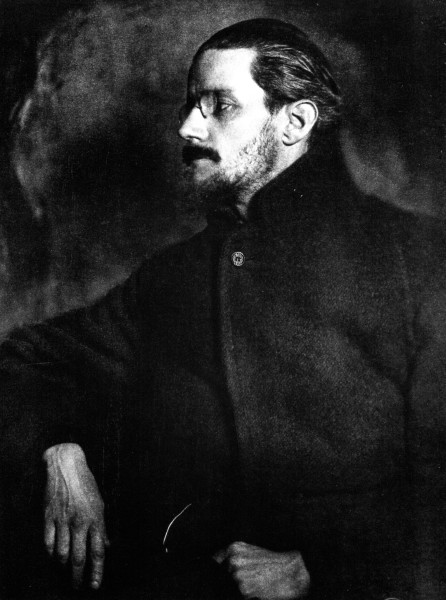

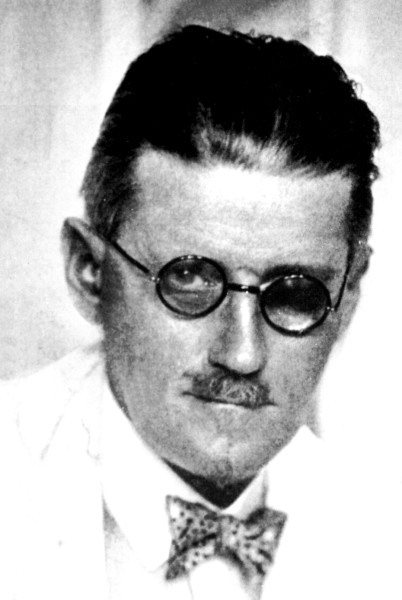

James Joyce, Paris, 1930

To demonstrate the operation of the portmanteau and to explore the reasons why, for all their superficial similarity, the portmanteau and the pun are very different kinds of linguistic deviation, a specific example is needed. The following passage was chosen at random, and the points I make about it could be made about any page of Finnegans Wake.

And stand up tall! Straight. I want to see you looking fine for me. With your brandnew big green belt and all. Blooming in the very lotust and second to nill, Budd! When you’re in the buckly shuit Rosensharonals near did for you. Fiftyseven and three, cosh, with the bulge. Proudpurse Alby with his pooraroon Eireen, they’ll. Pride, comfytousness, enevy! You make me think of a wonderdecker I once. Or somebalt that sailder, the man megallant, with the bangled ears. Or an earl was he, at Lucan? Or, no, it’s the Iren duke’s I mean. Or somebrey erse from the Dark Countries. Come and let us! We always said we’d. And go abroad. (Finnegans Wake, Faber/Viking 1939, p. 620)

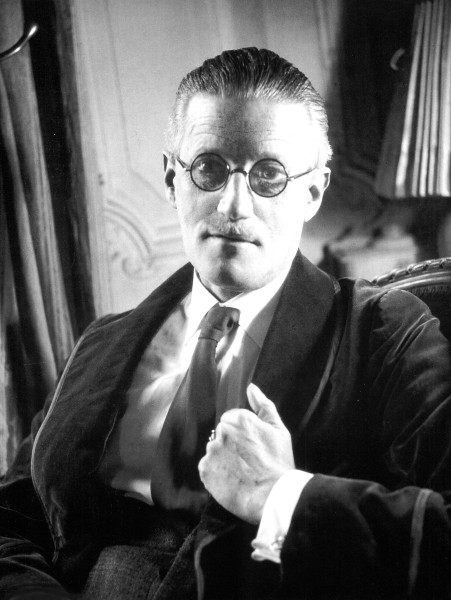

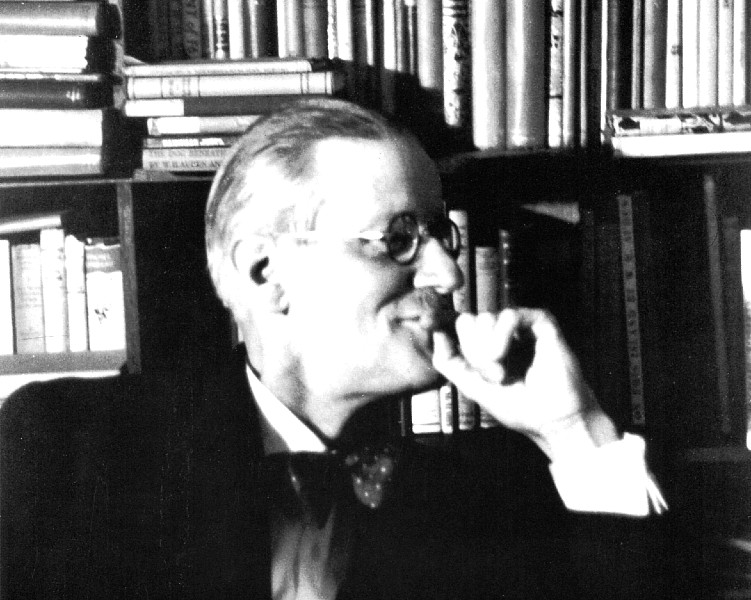

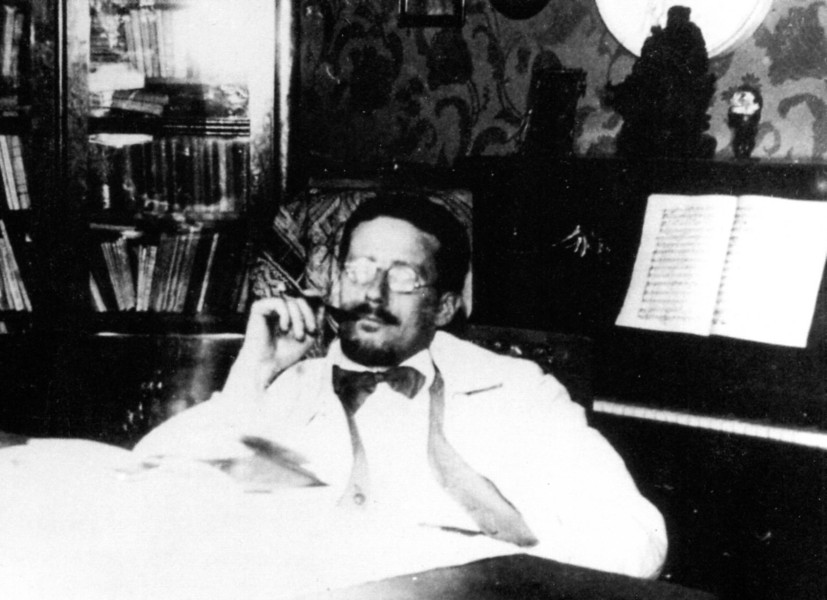

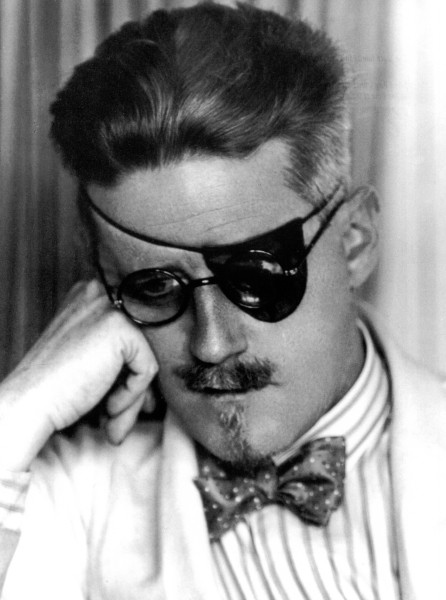

James Joyce, Paris, mid-1930s | Photo: Boris Lipnitzki

At the risk of seeming to posit the very things I have said the text undermines—themes, plot, characters—let me tender a bald and provisional statement of some of the threads that can be traced through the passage, in order to establish an initial orientation. The predominant ‘voice’ in this part of the text—its closing pages—is what Joyce designated by ‘A’, the shifting cluster of attributes and energies often associated with the initials ALP and the role of wife and mother. The addressee is primarily the group of characteristics indicated by ‘M’, the male counterpart frequently manifested as the letters HCE. Two of the prominent narrative strands involving this couple in the closing pages are a walk around Dublin in the early morning and a sexual act, and both are fused with the movement of the river Liffey flowing through Dublin into the sea.

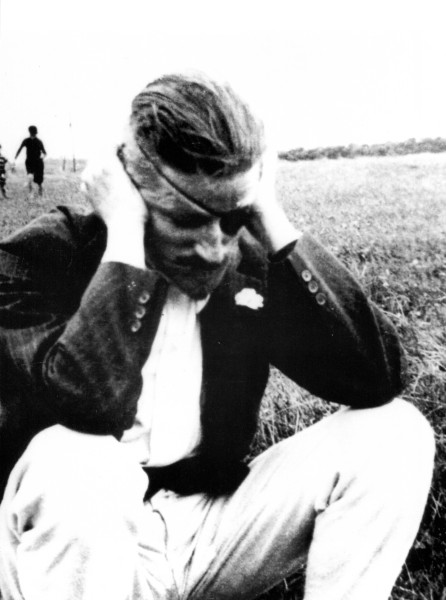

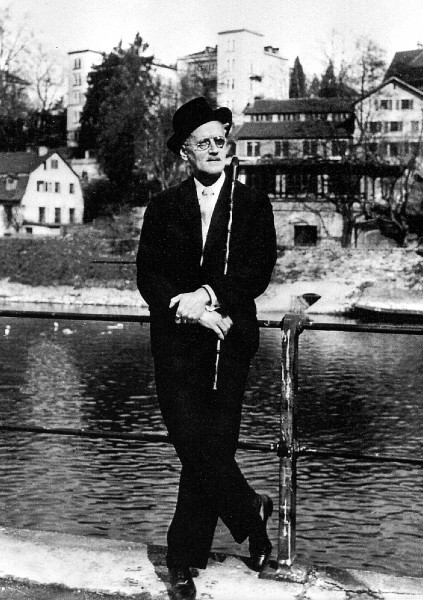

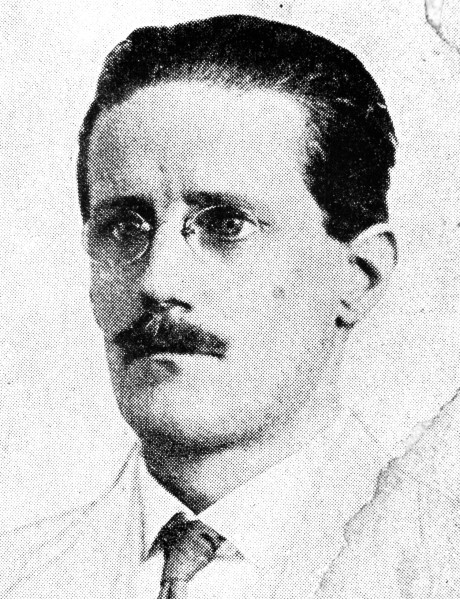

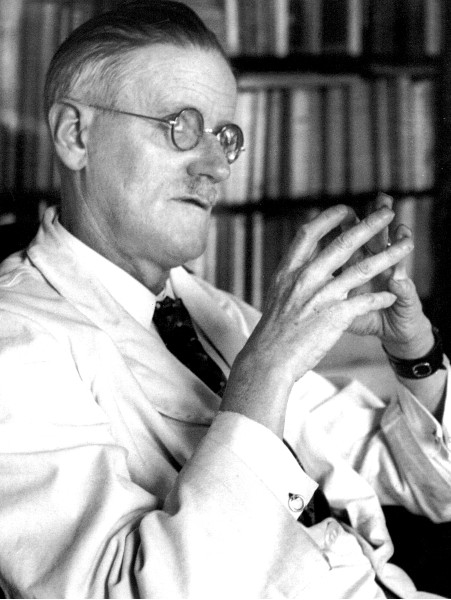

James Joyce, south of France, 1922

Contradictory tones and modes of address are blended, in particular the eager admiration of a young girl for her energetic lover and the disappointment of the aging wife with her now impotent husband. Here ALP is asking HCE to don his new, expensive clothes and go out with her on a jaunt, but she is also inviting him to demonstrate his naked sexual potency. At the same time what we hear is the river addressing the city of Dublin (reversed in ‘nill, Budd’), with its green belt and modern comforts. The relationship is also reminiscent of that between Molly and Leopold Bloom in Ulysses. ‘Blooming in the very lotust’ points to the earlier novel, especially the ‘Lotus-Eaters’ chapter; Sinbad the Sailor (‘somebalt that sailder’) is also associated with Bloom as he goes to bed in ‘Ithaca’; and Molly’s own closing chapter has something in common with ALP’s final monologue. It includes, too, the exploitative relationship of England and Ireland (‘Proud-purse Alby with his pooraroon Eireen’: perfidious Albion and poor Eire or Erin).

James Joyce with his daughter Lucia, Ostend (Belgium), 1924

The passage enunciates a series of ALP’s sexual memories, all of which turn out to be memories of HCE in one or other of his guises: as sailor (Sinbad, Magellan, and Vanderdecken, the captain of the Flying Dutchman); as military figure (the man with the bandolier, the duke of Wellington, and the earl of Lucan—whether the hero of the Williamite wars or the Lord Lucan who fought at Balaclava); and as the stranger (the man with earrings, the man from the Dark Countries) who is also an Irishman (not only Wellington but Lucan as a village on the Liffey, ‘Iren’ as Ireland, and ‘erse’ as Irish). That the exploits of these figures are partly sexual (or excretory, for the two are not kept distinct in the Wake) emerges from the ‘gallant’ of ‘megallant,’ ‘erse’ understood as ‘arse,’ and another echo of Ulysses, this time of Bloom’s pamphlet advertising the ‘Wonderworker,’ ‘the world’s greatest remedy for rectal complaints’ (17.1820).

James Joyce, Scheveningen (Holland), late 1920s

Once phallic suggestions begin to surface, they can be discovered at every turn: a few examples would be ‘stand up,’ ‘straight,’ ‘I want to see you’, bod (pronounced bud) as Gaelic for ‘penis,’ ‘cosh’ (a thick stick), ‘bulge,’ the ‘wonderdecker’ again (decken in German is to copulate), the stiffness of iron, and the Wellington monument. And the evident ellipses (reminiscent of those in the ‘Eumaeus’ episode of Ulysses) can easily be read as sexual modesty: ‘a wonderdecker I once … ,’ ‘the Iren Duke’s … ,’ ‘Come and let us … ,’ ‘We always said we’d….’ I have provided only an initial indication of some of the meanings at work here, and one could follow other motifs through the passage: flowers, sins (several of the seven deadly ones are here), tailoring and sailing (the two often go together in the Wake), and battles. All of these are associated in one way or another with sex.

James Joyce, Paris, c.1930

Let us focus now on one word from the passage, ‘shuit.’ To call it a word is of course misleading—it is precisely because it is not a word recognized as belonging to the English language that it functions as it does, preventing the immediate move from material signifier to conceptual signified. Unlike the pun, which exists only if the context brings it into being, the portmanteau refuses, by itself, any single meaning, and in reading we therefore have to nudge it toward other signifiers whose meanings might prove appropriate. Let us, first of all, ignore the larger context of the whole book and concentrate—as we would for a pun—on the guidance provided by the immediate context. We seem to be invited to take ‘shuit’ as an item of clothing, one that can have the adjective ‘buckly’—with buckles—applied to it. Three lexical items offer themselves as appropriate: suit, shirt, shoes. The first two would account for the portmanteau without any unexplained residue, but ‘buckly’ seems to point in particular to shoes, partly by way of the nursery rhyme ‘One, two, buckle my shoe.’ A writer employing orthodox devices of patterning at the level of the signifier might construct a sentence in which the separate words suit, shirt, and shoes all occur in such a way as to make the reader conscious of the sound-connections between them, thus creating a ‘nonce-constellation’, but it would be a rather feeble, easily ignored, device.

James Joyce, Paris, late 1930s

‘Shuit’ works more powerfully because it insists on a productive act of reading, because its effects are simultaneous, and because the result is an expansion of meaning much more extensive than that effected by the pun. The pun carries a powerful charge of satisfaction: the specter of a potentially unruly and ultimately infinite language is raised only to be exorcized, the writer and reader are still firmly in control, and the language has been made to seem even more orderly and appropriate than we had realized, because an apparently arbitrary coincidence in its system has been shown to be capable of semantic justification. But ‘shuit’ and its kind are more disturbing. The portmanteau has the effect of a failed pun—the patterns of language have been shown to be partially appropriate but with a residue of difference where the pun found only happy similarity. And though the context makes it clear that the passage is about clothing and thereby seems to set limits to the word’s possible meanings, one cannot escape the feeling that the process, once started, may be unstoppable. No reference book or mental register exists to tell us all the possible signifiers that are or could be associated in sound with ‘shuit,’ and we have learned no method of interpretation to tell us how to go about finding those signifiers or deciding at what point the connection becomes too slight to be relevant. Certainly other signifiers sound like ‘shuit,’ and if similarities of sound can have semantic implications, how do we know where to draw the boundary?

James Joyce, Paris, 1938 | Photo: Gisèle Freund

The answer to this question may seem straightforward: like the pun, the portmanteau will contain as much as the verbal context permits it to contain and no more. But the answer brings us to a fundamental point about the Wake, because the context itself is made up of puns and portmanteaux. So far I have spoken as if the context were a given, firm structure of meaning which has one neatly defined hole in it, but this notion is of course pure interpretative fiction. The text is a web of shifting meanings, and every new interpretation of one item recreates afresh the context for all the other items. Having found suit in ‘shuit,’ for example, one can reinterpret the previous word to yield the phrase birthday suit, as a colloquial expression for ‘nakedness,’ nicely epitomizing the fusion of the states of being clothed and unclothed which the passage implies—one more example of the denial of the logic of opposites which starts to characterize this text with its very title. Thus a ‘contextual circle’ is created whereby plurality of meaning in one item increases the available meanings of other items, which in turn increase the possibilities of meaning in the original item. The longer and denser the text, the more often the circle will revolve, and the greater will be the proliferation of meanings.

James Joyce, Zurich, 1938 | Photo: Carola Giedion-Welcker

It is important to note, however, that the network of signification remains systematic. In a text as long and as densely worked as Finnegans Wake, however, the systematic networks of meaning could probably provide contexts for most of the associations that individual words might evoke—though an individual reader could not be expected to grasp them all. This sense of a spiraling increase in potential meaning is one of the grounds on which the Wake is left unread, but is this not an indication of the way all texts operate? Every item in a text functions simultaneously as a sign whose meaning is limited (but not wholly limited) by its context and as a context limiting (but not wholly limiting) the meaning of other signs. There is no escape from this circle, no privileged item that yields its meaning apart from the system in which it is perceived and which can act as a contextless context or transcendental fixing-point to anchor the whole text. The enormous difference between Finnegans Wake and other literary works is, perhaps, a difference in degree, not in kind.

James Joyce, Zurich, 1938 | Photo: Carola Giedion-Welcker

The next word, ‘Rosensharonals,’ provides another example of the operation of contexts in the Wake. As an individual item it immediately suggests ‘Rose of Sharon,’ a flower (identified with crocus, narcissus, and others) to go with bloom, lotus, and bud and to enhance further the springlike vitality of the male or his sexual organ. It gives us a reference to the Song of Solomon (itself a sexual invitation), reinforcing the text’s insistence that apparently ‘natural’ human emotions are cultural products: love and sexual desire in this passage are caught up not only with the Hebraic tradition but also with Buddhism (both in the lotus and in ‘Budd’), with Billy Budd (a story whose concerns are highly relevant), with Sinbad the Sailor (as a tale from the Arabian Nights or as a pantomime), and with popular songs (Eileen Aroon—’Eileen my darling’—and phrases from ‘I will give you the keys to heaven’). The sense of new beginnings is also heightened by a suggestion of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. In the context of clothing, however, the name sounds more like that of the Jewish tailor who made the garment in question: ‘the buckly shuit Rosensharonals near did for you,’ bringing to mind the story of Kersse the tailor and the Norwegian captain from earlier in the book (311-32), a story that involves a suit with a bulge in it, apparently made necessary by a hunchback.

James Joyce, Bognor (Sussex), 1923

But once we move to the context of the whole work, another story, from the same earlier chapter (337-55), comes into prominence: the tale of Buckley and the Russian general, which appears in the text at many points and in many guises. Buckley is a common Irish soldier in the Crimean War who comes upon a Russian general with his pants down, in the act of defecating, and either does or does not shoot at him. The story interweaves with other stories of encounters involving exposure and/or voyeurism, such as the much-discussed event in Phoenix Park involving HCE, two girls, and three soldiers. It has to do with the attack by the younger generation on the older, and the older generation’s fall from power before the younger, the drunkenness of Noah and the drugging of Finn MacCool by his young bride being other versions. (It is typical of the Wake’s method that an indecent anecdote which Joyce heard from his father is accorded the same status as religious myth and epic narrative.) So in the middle of a passage of praise for the virility of HCE comes a reminder of his loss of control, and ‘near did for you’ becomes a reference not to tailoring but to an attempt at, or a resisted temptation to, murder. And our portmanteau shuit unpacks itself further, yielding both shoot and shit.

James Joyce, Zurich, 1919

My aim is not to demonstrate the plurality of meaning in Joyce’s portmanteaux; that is easily done. It is to focus on the workings of a typical portmanteau to show both how crucial they are to the method of Finnegans Wake and how they help make the book conceivable as a central, rather than a peripheral, literary text. The portmanteau shatters any illusion that the systems of difference in language are fixed and sharply drawn, reminding us that signifiers are perpetually dissolving into one another: in the never-ending diachronic development of language; in the blurred edges between languages, dialects, registers, idiolects; in the interchange between speech and writing; in errors and misunderstandings, unfortunate or fruitful; in riddles, jokes, games, and dreams. Finnegans Wake insists that the strict boundaries and discrete elements in a linguist’s ‘grammar of competence’ are a neoplatonic illusion.

James Joyce, Trieste, 1915 | Photo: Ottocaro Weiss

But the portmanteau problematizes even the most stable signifier by showing how its relations to other signifiers can be productive; we find that we can quite easily relate suit to shirt just as we do in fact relate suit to suits or suited. Instead of saying that in learning a language we learn to ascribe meaning to a few of the many patterns of sound we perceive, it may be as true to say that we learn not to ascribe meaning to most of those connections (Freud takes this view in his book on jokes)—until we are allowed to do so again to a certain degree in rhetoric and poetry, and with almost complete abandon in Finnegan Wake. The result, of course, is that as we read the Wake we test for their possible associations not only the obvious portmanteaux but every apparently normal word as well. The phrase ‘bangled ears’ does not present itself as a portmanteau, and in most texts it would be read as a somewhat odd, but semantically specific, conjunction of adjective and noun. But the context of the Wake’s portmanteau style encourages us, as I have suggested, to hear it also as ‘bandolier,’ to combine the attributes of the savage or stranger with those of the soldier. Even the most normal and innocent word will invite such treatment. Another theoretical distinction becomes blurred, that between synchronic and diachronic dimensions, because a pertinent meaning may be retrievable from the history of a word. ‘Erse,’ for instance, offers both a Middle English word for ‘arse’ and an early Scottish word for ‘Irish.’ Here, too, the Wake heightens a process that operates in all language, in spite of the Saussurean enterprise of methodically separating synchrony and diachrony.

James Joyce, Trieste, c.1919

The implications of the portmanteau word, or rather the portmanteau text, go further, however. The portmanteau undermines the notion of authorial intention, for instance, in a way quite foreign to the traditional pun. The pun in fact strengthens the illusion of intention as a presence within the text: part of the satisfaction to be found in an effective pun is the feeling of certainty, once the pun is grasped, that it was intended by its witty and resourceful author. The careful construction of context to allow both meanings equal force and to exclude all other meanings is not something that happens by accident, we feel, and this feeling makes the pun acceptable in certain literary environments because there is no danger that the coincidence thus exposed will enable language to wrest control from its users. But the portmanteau word, though its initial effect is often similar, has a habit of refusing to rest with that comforting sensation of ‘I see what the author meant.’ To find shirt and suit in shuit, and nothing else, might yield a satisfying response of that kind: ‘clearly what Joyce is doing is fusing those words into one,’ we say to ourselves. But when we note the claims for shoes, shoot, and shit as well, we begin to lose hold on our sense of an embodied intention. If those five are to be found, why not more?

James Joyce, Zurich, 1918

The polyglot character of the text, for instance, opens up further prospects. If French ears hear chute, one can hardly deny the relevance of the notion of a fall (or of the Fall) to the story of Buckley and the Russian general or to the temptation of HCE in the park. And why should any particular number of associations, in any particular number of languages, correspond to the author’s intention? Joyce has set in motion a process over which he has no final control—a source of disquiet for many readers. Some, however, are more willing to accept the vast scale of what the multilingual portmanteau opens up. In ‘Finnegans, Wake!’ Jean Paris observes that ‘once it is established, it must by its own movement extend itself to the totality of living and dead languages.

James Joyce, Zurich

And here indeed is the irony of the portmanteau style: the enthroning of a principle of chance which, prolonging the intentions of the author, in so far as they are perceptible, comes little by little to substitute for them, to function like a delirious mechanism, accumulating allusions, parodying analogies, and finally atomizing the Book’. But every text, not just this one, is ultimately beyond the control of its author, every text reveals the systems of meaning of which Derrida speaks in his consideration of the word pharmakon in Plato’s Phaedrus: ‘But the system here is not, simply, that of the intentions of an author who goes by the name of Plato. The system is not primarily that of what someone meant-to-say. Finely regulated communications are established, through the play of language, among diverse functions of the word and within it, among diverse strata or regions of culture’ (Dissemination, 95).

James Joyce, Paris, 1938 | Photo: Gisèle Freund

Similarly, the portmanteau word leaves few of the conventional assumptions about narrative intact: récit cannot be separated from histoire when it surfaces in the texture of the words themselves. When, for instance, the story of Buckley and the Russian general is woven, by the portmanteau method, into a statement about new clothing, it is impossible to talk in terms of the narration of a supposedly prior event. Rather, there is a process of fusion which enforces the realization that all stories are textual effects. Characters, too, are never behind the text in Finnegans Wake but in it; ALP, HCE, Buckley, and the Russian general have their being in portmanteau words, in acrostics, in shapes on the page—though this, too, is only a reinforcement of the status of all fictional characters.

James Joyce, Paris, late 1920s | Photo: Ruth Asch

Finally, consider the traditional analysis of metaphor and allegory as a relation between a ‘literal,’ ‘superficial’ meaning and a ‘figurative,’ ‘deep,’ ‘true’ meaning. The portmanteau word, and Finnegans Wake as a whole, refuses to establish such a hierarchical opposition, for anything that appears to be a metaphor is capable of reversal, the tenor becoming the vehicle, and vice versa. In the quoted passage we might be tempted to say that a literal invitation to go for a walk can be metaphorically interpreted as an invitation to sexual activity. At the level of the word one might say that ‘lotust’ is read literally as latest, a reference to fashion, but that the deeper meaning is lotus, with its implication of sensual enjoyment. But the only reason for saying that the ‘deeper’ meaning is the sexual one is our own preconception as to what counts as deep and what as superficial. All metaphor, we are made to realize by this text, is potentially unstable, kept in position by the hierarchies we bring to bear upon it, not by its inner, inherent division into literal and figurative domains.

James Joyce, Paris, late 1920s | Photo: Berenice Abbot

The fears provoked by Finnegans Wake’s portmanteau style are understandable and inevitable, because the consequences of accepting it extend to all our reading. Every word in every text is, after all, a portmanteau of sorts, a combination of sounds that echo through the entire language and through every other language and back through the history of speech. Finnegans Wake makes us aware that we, as readers, control this explosion, allowing only those connections to be effected which will give us the kinds of meaning we recognize—stories, voices, characters, metaphors, images, beginnings, developments, ends, morals, truths. We do not, of course, control it as a matter of choice. We are subject to the various grids that make literature and language possible at all—rules, habits, conventions, and all the boundaries that legitimate and exclude in order to produce meanings and values, themselves rooted in the ideology of our place and time.

James Joyce, Paris, 1937 | Photo: Josef Breitenbach

Nevertheless, to obtain a glimpse of the infinite possibility of meaning kept at bay by those grids, to gain a sense that the boundaries upon which our use of language depends are set up under specific historical conditions, is to be made aware of a universe more open to reinterpretation and change than the one we are usually conscious of inhabiting. For many of its readers Finnegans Wake makes that glimpse an experience of exhilaration and opportunity, and as a result the book comes to occupy an important place in their reading; but for many others it can be only a discouraging glimpse of limitless instability. So the book is treated as a freak, an unaccountable anomaly that merely travesties the cultural traditions we cherish, and its function as supplement and pharmakon, supererogatory but necessary, dangerous but remedial, is thereby prolonged.

James Joyce, Paris, 1926 | Photo: Berenice Abbott

When the Wake is welcomed, however, it is often by means of a gesture that simultaneously incapacitates it, either by placing it in a sealed-off category (the impenetrable and inexpressible world of the dream) or by subjecting it to the same interpretative mechanisms that are applied to all literary texts, as if it were no different: the elucidation of an ‘intention’ (aided by draft material and biography), the analysis of ‘characters,’ the tracing of ‘plot,’ the elaboration of ‘themes,’ the tracking down of ‘allusions,’ the identification of ‘autobiographical references,’ in sum, the whole panoply of modern professional criticism. The outright repudiation of the Joycean portmanteau is perhaps preferable to this industrious program of normalization and domestication. Samuel Johnson’s passionate lament for Shakespeare’s use of puns involves a fuller understanding of the implications of the pun than many an untroubled celebration of textual indeterminacy, and to be afraid of Finnegans Wake is at least to acknowledge, even if unconsciously, the power and magnitude of the claims it makes.

James Joyce, Paris, 1935

DEREK ATTRIDGE: THREE BOOKS

Derek Attridge, Joyce Effects

Derek Attridge, Work of Literature

Derek Attridge, Experience of Poetry

JAMES JOYCE READING ‘ANNA LIVIA PLURABELLE’ FROM ‘FINNEGANS WAKE’

James Joyce Centre (Dublin) – Notes on the Recording

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

Well, you know or don’t you kennet or haven’t I told you every telling has a taling and that’s the he and the she of it. Look, look, the dusk is growing. My branches lofty are taking root. And my cold cher’s gone ashley. Fieluhr? Filou! What age is at? It saon is late. ‘Tis endless now senne eye or erewone last saw Waterhouse’s clogh. They took it asunder, I hurd thum sigh. When will they reassemble it? O, my back, my back, my bach! I’d want to go to Aches-les-Pains. Pingpong! There’s the Belle for Sexaloitez! And Concepta de Send-us-pray! Pang! Wring out the clothes! Wring in the dew! Godavari, vert the showers! And grant thaya grace! Aman. Will we spread them here now? Ay, we will. Flip! Spread on your bank and I’ll spread mine on mine. Flep! It’s what I’m doing. Spread! It’s churning chill. Der went is rising. I’ll lay a few stones on the hostel sheets. A man and his bride embraced between them. Else I’d have folded and sprinkled them only. And I’ll tie my butcher’s apron here. It’s suety yet. The strollers will pass it by.

Charles-François Daubigny, Landscape with Washerwomen, c.1865

Six shifts, ten kerchiefs, nine to hold to the fire and this for the code, the convent napkins twelve, one baby’s shawl. Good mother Jossiph knows, she said. Whose head? Mutter snores? Deataceas! Wharnow are aile her childer, say? In kingdome gone or power to come or gloria be to them farther? Allalivial, allalluvial! Some here, more no more, more again lost alla stranger. I’ve heard tell that same brooch of the Shannons was married into a family in Spain. And all the Dunders de Dunnes in Markland’s Vineland beyond Brendan’s herring pool takes number nine in yangsee’s hats. And one of Biddy’s beads went bobbing till she rounded up lost histereve with a marigold and a cobbler’s candle in a side strain of a main drain of a manzinahurries off Bachelor’s Walk. But all that’s left to the last of the Meaghers in the loup of the years prefixed and between is one kneebuckle and two hooks in the front. Do you tell me that now? I do in troth. Orara por Orbe and poor Las Animas! Ussa, Ulla, we’re umbas all! Mezha, didn’t you hear it a deluge of times, ufer and ufer, respund to spond? You deed, you deed! I need, I need! It’s that irrawaddyng I’ve stoke in my aars. It all but husheth the lethest zswound.

Charles-François Daubigny, Washerwomen at the Oise near Valmondois, 1865

Oronoko! What’s your trouble? Is that the great Finnleader himself in his joakimono on his statue riding the high horse there forehengist? Father of Otters, it is himself! Yonne there! Isset that? On Fallareen Common? You’re thinking of Astley’s Amphitheayter where the bobby restrained you making sugarstuck pouts to the ghostwhite horse of the Peppers. Throw the cobwebs from your eyes, woman, and spread your washing proper. It’s well I know your sort of slop. Flap! Ireland sober is Ireland stiff. Lord help you, Maria, full of grease, the load is with me! Your prayers. I sonht zo! Madammangut! Were you lifting your elbow, tell us, glazy cheeks, in Conway’s Carrigacurra canteen? Was I what, hobbledyhips? Flop! Your rere gait’s creakorheuman bitts your butts disagrees. Amn’t I up since the damp dawn, marthared mary allacook, with Corrigan’s pulse and varicoarse veins, my pramaxle smashed, Alice Jane in decline and my oneeyed mongrel twice run over, soaking and bleaching boiler rags, and sweating cold, a widow like me, for to deck my tennis champion son, the laundryman with the lavandier flannels?

Eugène Boudin, Washerwomen by the River, c.1883

You won your limpopo limp fron the husky hussars when Collars and Cuffs was heir to the town and your slur gave the stink to Carlow. Holy Scamander, I sar it again! Near the golden falls. Icis on us! Seints of light! Zezere! Subdue your noise, you hamble creature! What is it but a blackburry growth or the dwyergray ass them four old codgers owns. Are you meanam Tarpey and Lyons and Gregory? I meyne now, thank all, the four of them, and the roar of them, that drayes that stray in the mist and old Johnny MacDougal along with them. Is that the Poolbeg flasher beyant, pharphar, or a fireboat coasting nyar the Kishtna or a glow I behold within a hedge or my Garry come back from the Indes? Wait till the honeying of the lune, love! Die eve, little eve, die! We see that wonder in your eye. We’ll meet again, we’ll part once more. The spot I’ll seek if the hour you’ll find. My chart shines high where the blue milk’s upset. Forgivemequick, I’m going! Bubye! And you, pluck your watch, forgetmenot. Your evenlode. So save to jurna’s end! My sights are swimming thicker on me by the shadows to this place. I sow home slowly now by own way, moyvalley way. Towy I too, rathmine.

Léon Lhermitte (1844-1925), Washerwomen on the Banks of the Marne

Ah, but she was the queer old skeowsha anyhow, Anna Livia, trinkettoes! And sure he was the quare old buntz too, Dear Dirty Dumpling, foostherfather of fingalls and dotthergills. Gaffer and Gammer we’re all their gangsters. Hadn’t he seven dams to wive him? And every dam had her seven crutches. And every crutch had its seven hues. And each hue had a differing cry. Sudds for me and supper for you and the doctor’s bill for Joe John. Befor! Bifur! He married his markets, cheap by foul, I know, like any Etrurian Catholic Heathen, in their pinky limony creamy birnies and their turkiss indienne mauves. But at milkidmass who was the spouse? Then all that was was fair. Tys Elvenland! Teems of times and happy returns. The seim anew. Ordovico or viricordo. Anna was, Livia is, Plurabelle’s to be. Northmen’s thing made southfolk’s place but howmulty plurators made eachone in person? Latin me that, my trinity scholard, out of eure sanscreed into oure eryan. Hircus Civis Eblanensis! He had buckgoat paps on him, soft ones for orphans. Ho, Lord! Twins of his bosom. Lord save us! And ho! Hey? What all men. Hot? His tittering daughters of. Whawk?

Hippolyte-Camille Delpy (1842 – 1910) , Washerwomen by the River at Sunset

Can’t hear with the waters of. The chittering waters of. Flittering bats, fieldmice bawk. talk. Ho! Are you not gone ahome? What Thom Malone? Can’t hear with bawk of bats, all thim liffeying waters of. Ho, talk save us! My foos won’t moos. I feel as old as yonder elm. A tale told of Shaun or Shem? All Livia’s daughter-sons. Dark hawks hear us. My ho head halls. I feel as heavy as yonder stone. Tell me of John or Shaun? Who were Shem and Shaun the living sons and daughters of? Night now! Tell me, tell me, tell me, elm! Night night! Telmetale of stem or stone. Beside the rivering waters of, hitherandthithering waters of. Night!

Jean-François Millet, Washerwomen, 1855

JAMES JOYCE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part One Chapter 1

̶ Are you French?

̶ Half French.

̶ And what’s the other half?

̶ Swiss. My father’s French, my mother’s Swiss.

̶ Suisse romande?

̶ Yes, but I live in Zürich.

̶ Ah! I was in Zürich last year. What a city! A lake, a mountain and two rivers are its treasures. Yssel that the Limmat?

̶ Pardon?

̶ Yssel that the Limmat?

̶ Ah! That’s a good one.

̶ It’s from Finnegans Wake. James Joyce. The greatest writer in the English language! After Shakespeare, of course. But he’s the greatest in any language.

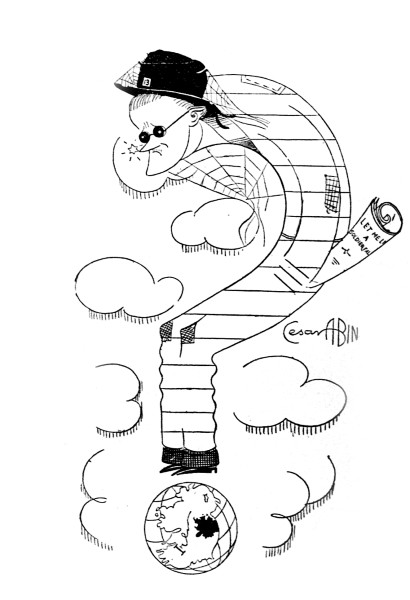

James Joyce | Drawing: César Abin, 1932

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part One Chapter 3

̶ And Samuel Beckett, writing about Joyce’s Work in Progress, said, ‘His writing is not about something; it is that something itself’. Do you see the difference?

̶ Yes. Music.

̶ Exactly!

̶ What’s Work in Progress?

̶ Finnegans Wake. The dream book.

̶ I’ve heard it’s a nightmare. To read.

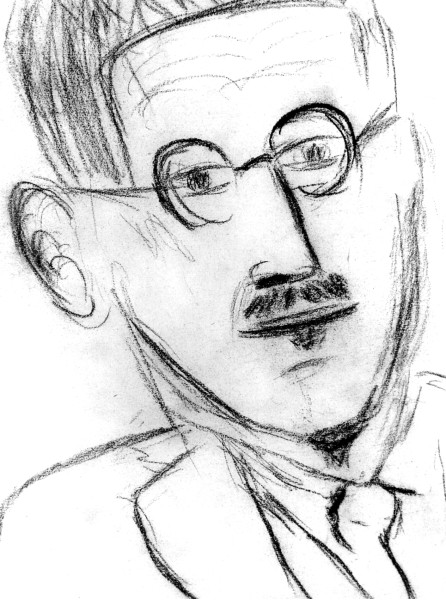

James Joyce | Drawing: Lucia Joyce

̶ Do you know there’s a James Joyce Foundation in Zürich?

̶ Yes. I was there last year. I heard a lecture on Nora Barnacle.

̶ Who’s she?

̶ She was Joyce’s wife.

̶ What a name!

̶ Yeah. Joyce’s father used to say, ‘With a name like that, she’ll never leave him’!

̶ A clinging barnacle!

̶ Except that it was he who clung to her. She was an amazing woman. ‘Her image had passed into his soul forever.’

̶ What?

̶ ‘Her eyes had called him and his soul had leapt at the call.’

̶ I see.

James Joyce | Drawing: Augustus John, 1930

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 14

Djuna Barnes—the slow narcotic of Nightwood, the anatomy of love: through a black diamond, lucidly.

̶ You know, tipping the velvet, tongue in cheek.

The joyful wit of her Vanity Fair portrait, white wine with Joyce at the Deux Magots.

̶ In a word, louche, but ironic.

Sticking her tongue in Nicole’s ear, Héloïse flicks it languorously. Everybody laughs.

Djuna Barnes, James Joyce, 1922

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 17

̶ This is Cassiopeia. Can you find it in the sky?

̶ I think so. It’s the only constellation I know well.

Scanning the inexhaustible hierophany that seems to be absorbing me, I find where to look and bring the binoculars to my eyes.

̶ Yes, I see it.

̶ You do know it well, Sprague. And how did that come about?

I lay down the binoculars.

̶ ‘His shadow lay over the rocks as he bent, ending. Why not endless till the farthest star? Darkly they are there behind this light, darkness shining in the brightness, delta of Cassiopeia, worlds.’

̶ James Joyce?

̶ Yes. That’s what kicked my love for the English language into overdrive. That was when I understood that with sound and rhythm, you can create a world. I’d wanted to do it in music, but I knew I didn’t have the talent. So I chose the next best thing—words.

James Joyce | Drawing: Wyndham Lewis, 1921

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 12

‘What bitter’s love but yurning, what sour lovemutch but a bref burning till shee that drawes dothe smoake retourne?’ Lying on the sofa in our suite while you’re out shopping, I hone my wit on the stone of Finnegans Wake. On cue, you return just when I get to Issy’s interrogation: ‘Of I be leib in the immoralities? O, you mean the strangle for love and the sowiveall of the prettiest?’ You’re used to my laughing out loud at the Wake, so you simply say:

̶ Hi.

̶ Hi.

Glossing ‘It’s Dracula’s nightout. For creepsake don’t make a flush!’, I call out:

̶ Did you find what you were looking for?

̶ I did, my darling.

On cat’s paws you’ve come to me; I turn around and I’m transfixed …

James Joyce | Drawing: Augustus John, 1930