HAMLET

SHAKESPEARE – HAMLET AND OPHELIA: HAMLET’S VIRGIN

William Kerrigan

All images from Kenneth Branagh’s film of Hamlet, 1996.

From William Kerrigan, Hamlet’s Perfection (The John Hopkins University Press, 1996) pp. 94-109. Text edited in parts for the sake of concision.

Shakespeare does many things well, but immense—today we would say excessive—moral revulsion is a favorite inspiration in the tragedies and romances. This pattern of a lost faith followed by global disillusionment shapes most of the plays written after Hamlet. But Hamlet itself inverts the pattern. Disillusionment has taken place, and its effects felt, as the play begins. As a revenge tragedy, the drama’s central focus is on when and how the hero will fulfill his father’s task. But the delay makes room for another and more difficult achievement that in Act 5 ultimately absorbs the vengeance motive itself. In its thoroughness and dramatic extension, this achievement has no precedent in Shakespearean tragedy. Out of a ‘flat’ world overrun by ‘things gross in nature’ Hamlet, reversing the disillusionment pattern, will make a complex ideal.

Kenneth Branagh as Hamlet

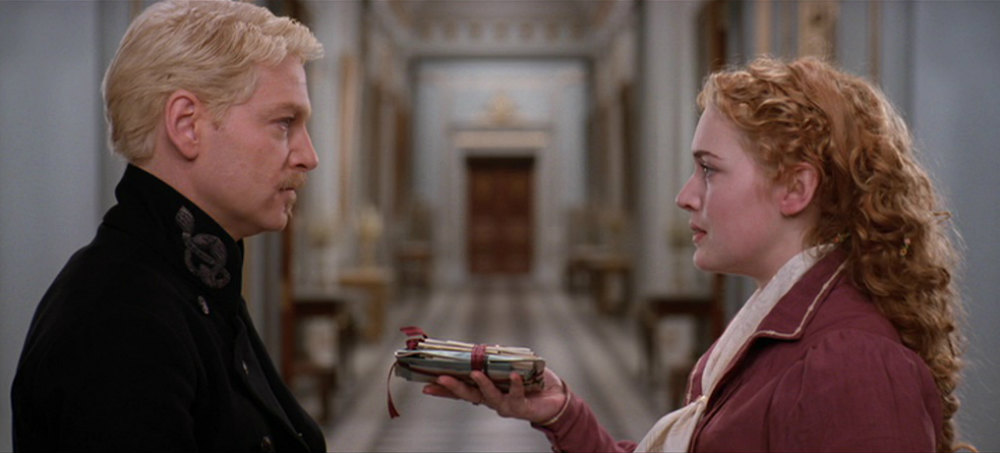

Hamlet with Kate Winslet as Ophelia

I begin with the rejection scene. Polonius and Claudius have taken positions of concealment. Hamlet has just finished the most famous speech in English drama. The currents have gone awry and the name of action has been lost. Ophelia comes into view reading a devotional book. She has something in her hand. Hamlet must shift from deep privacy to conversation:

Soft you now.

The fair Ophelia! Nymph, in thy orisons

Be all my sins remember’d. (3.1.88-90)

Some readers think Hamlet is trying to remove Ophelia from the scene of the forthcoming tragedy. Others think he knows she is being manipulated by Claudius and Polonius, and wishes to disentangle her from all the plots now set in motion by sending her to a nunnery. Still others feel that he is too angry at women to have much in mind beyond hurting his ex-girlfriend. So the tone of this opening line is consequential.

With ‘To be or not to be’ still ringing in our ears, Hamlet’s use of the term ‘sins’ names something loudly absent from the soliloquy. There he lists the evils of life as ills we bear and shocks that flesh is heir to. Evil seems wholly external, and the turning point of the speech, the ‘rub’ that deflects Hamlet’s thoughts from the happiness of death to ‘the respect that makes calamity of so long life,’ must be inferred by the audience:

To sleep, perchance to dream—aye, there’s the rub:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause (3.1.65-68)

I think ‘Nymph, in thy orisons be all my sins remember’d’ is indeed grave and solemn, the words of a man who has flirted with skeptical self-determination but, pulled back by the dread of God, now submits to divine judgment in an almost Pascalian frame of mind.

Hamlet

Hamlet and Ophelia

But I hear bitter sarcasm in ‘The fair Ophelia!’ It was, after all, the summary site of this fairness, her countenance, that Hamlet visited her closet to hold before him and stare at closely. As this scene unfolds, we will learn that fair is a highly charged word for Hamlet.

Obeying her instructions, Ophelia returns his ‘remembrances.’ Hamlet first denies giving her anything: ‘No, not I. I never gave you aught’. Metrical stress puts a telling spin on the first ‘I’ that probably passes to the second: Not I, I never gave you aught. He is announcing in words what the wordless visit conveyed. He is different now. As he says more conventionally later in the scene, ‘I did love you once’. Women, love, sweetness, gifts, and marriage are no longer for him. Ophelia is twice unsuccessful at handing back the packet (‘I pray you now receive them,’ ‘Take these again’), and in the end seems to force it into his hands (‘There, my lord’). His letters and tokens, the life of another Hamlet, a man who wanted above all to be believed in his love suit, now rest in his hands—the ocular proof that his suit is not believed.

Ophelia’s rejection might once have devastated him, but now ironic laughter at the difference in himself kicks off another episode of wildness:

Hamlet: Ha! Ha! Are you honest?

Ophelia: My lord?

Hamlet: Are you fair?

Ophelia: What means your lordship?

Hamlet: That if you be honest and fair, your honesty should admit no discourse to your beauty.

Ophelia: Could beauty, my lord, have better commerce than with honesty?

Hamlet: Aye, truly, for the power of beauty will sooner transform honesty from what it is to a bawd than the force of honesty can translate beauty into his likeness. This was sometime a paradox, but now the time gives it proof. I did love you once.

Hamlet and Ophelia

Hamlet and Ophelia

‘Ha! Ha!’ turns the scene to prose, and the first thing that the new wild Hamlet wants to talk about is the sad contemporary state of the virgin/whore split. We now can be pretty certain that ‘The fair Ophelia!’ was sarcastic. Fair stands for the whorish side of woman, while honesty stands for the virginal side. The time gives it proof—Gertrude gives it proof—that the bad fair must corrupt the good honest.

But the split inhabits a space in-between man and woman. It takes two to make an honest woman a bawd. There are Claudiuses in the world, and something of Claudius in all men, Hamlet included: ‘You should not have believed me; for virtue cannot so inoculate our old stock but we shall relish of it. I loved you not’. Doing unto Ophelia what Gertrude has done unto him, Hamlet serves as her disillusioner about the opposite sex. Sin is original in men as well as women. Virtue in men, like honesty in women, cannot escape the rank unweeded garden of a fallen world. As an example of how little men can be trusted, he denies the past love he has just affirmed. Love is on, then off, in the rhythm of the scene, which is reminiscent of the game played with flower petals. I never gave you aught. I did love you once. I loved you not. Hamlet seems at an impasse, spinning his wheels.

Hamlet and Ophelia

Hamlet and Ophelia

Hamlet proceeds to give Ophelia in a wild and extreme form the same lesson that Laertes and Polonius have urged on her. Men are not honest. The lecture begins with the scene’s signature line:

Get thee to a nunnery. Why, wouldst thou be a breeder of sinners? I am myself indifferent honest, but yet I could accuse me of such things that it were better my mother had not borne me. I am very proud, revengeful, ambitious, with more offences at my beck than I have thoughts to put them in, imagination to give them shape, or time to act them in. What should such fellows as I do crawling between earth and heaven? We are arrant knaves all, believe none of us. Go thy ways to a nunnery. Where’s your father?

Between the two injunctions to go to a nunnery, Hamlet presents a fairly exhaustive revelation of his new selfhood. The strain of self-accusation is loud and clear. He shows her his desire to be Avenging Night, but in such a form—not enough thoughts, imagination, or time—as to betray the paralysis he feels.

Life is purposeless and corrupt. ‘I could accuse me of such things that it were better my mother had not borne me’ exposes one of his deepest ambivalences. The statement has a ‘to be’ meaning (it were better that his mother had not borne him because he intends to hurt her and Claudius) and a ‘not to be’ meaning (it were better not to be born, not to have to discover that there is no safe escape from sullied flesh and the ills it must bear). Once concerned to be believed as a lover, he is now just as insistent on not being believed. The new self repeats in negative the gestures of the old.

Hamlet and Ophelia

Hamlet and Ophelia

Hamlet’s four repetitions of his chosen refrain—‘Get thee to a nunnery’—vary the verb from get to go. Intransitive get means ‘to succeed in coming or going to, from, into, out of,’ and go is simply the ‘verb of motion, expressing a movement irrespective of the point of departure or destination’ (OED): in his ‘sole commandment’ Hamlet literally finds the name of action. This declaration does fall on the side of past love. He cared for her enough to direct her out of the marketplace of marriage. The injunction to be quick on the get-go is tender as well as angry. He can do nothing but crawl along with his negatives, delaying. She, on the other hand, might get and go, renouncing the world of marriage and entering a nunnery, where physical fairness counts for nothing. She has not been visited by a ghost. She has available to her a choice, a way out, that is world-rejecting but not suicidal. She can be (a nun) and not be (a breeder of sinners). Facing a whorish world without ideals, Hamlet tries to make a virgin.

It has long been debated whether the whorish sense of ‘nunnery’—‘brothel,’ derived from ‘whore’, ‘nun of Venus’—belongs to the intentions of the scene. Certainly the virginal sense is paramount. He is not telling her to get herself to a whorehouse. But with four repetitions it seems plausible that the audience would have heard the evil half of this definitively split word. In my view the power of the scene depends on the backdrop of prostitution. Out of this stew of corruption in Hamlet’s mind emerges the possibility of an ideal woman. The corrupt sense still hangs about the virtuous, for Hamlet cannot so inoculate our old stock of words but they shall relish of it. When Gertrude remarried, the split collapsed into ‘Frailty, thy name is woman!’ What is there to do but make the split again, and out of lustful frailty retrieve honor and honesty?

Hamlet and Ophelia

Hamlet and Ophelia

The to-and-fro between man and woman, his sins and her sins, continues. Hamlet’s first reason for getting to a nunnery stems from the sins of men, the second from the sins of women. In another lingering farewell, anticipating the closet scene with Gertrude, Hamlet finds time to explore both sides of the question.

Hamlet: If thou dost marry, I’ll give thee this plague as a dowry: be thou as chaste as ice, as pure as snow, thou shalt not escape calumny. Get thee to a nunnery, farewell. Or if thou wilt needs marry, marry a fool; for wise men know well enough what monsters you make of them. To a nunnery, go—and quickly too. Farewell.

Ophelia: Heavenly powers, restore him.

Hamlet: I have heard of your paintings well enough. God hath given you one face and you make yourselves another. You jig and amble, and you lisp, you nickname God’s creatures, and make your wantonness your ignorance. Go to, I’ll no more on’t, it hath made me mad. I say we will have no more marriages. Those that are married already—all but one—shall live; the rest shall keep as they are. To a nunnery, go.

The calumny inspired by the virgin/whore split seems at first a trumped-up charge, born of misogyny, then a just accusation motivated by a wife’s fooling around. This second possibility inspires a bout of woman-baiting: you in ‘God hath given you one face’ surely means ‘you women’. The godless superficialities of the sex drive him mad. The ‘fair’ face of a woman is whorish, and so is her painted one. A conviction of universal female dishonor drives him to impatience. Yet he continues, as the impatience grows, to point toward his ideal. Wherever the split is, in men or in women, a matter of valuing or a matter of affected merit, she can escape in a nunnery; and Hamlet exits on ‘go’, the imperative of action. In his mind, the possibility of a feminine ideal is threatened every moment with destruction. The exiting ‘go’ brilliantly summarizes the confusion throughout about the locus of the threat: I can no longer stand to be in your presence, you should no longer be able to stand my presence.

Hamlet and Ophelia

The Mousetrap stage, Hamlet, Kenneth Branagh

To study the fate of this new ideal, we must revisit the closet scene. Hamlet cannot salvage purity from wrecked femininity without confronting its source, and he will bring to his audience with Gertrude the same jarring combination of anger and incipient idealism we have just observed in the rejection scene. But between the encounters with Ophelia and Gertrude lies the assembly of the play-within-the-play. The purpose is to catch the conscience of the king, but his repartee suggests that womanhood preoccupies the prince. The ideal trumpeted during the rejection scene, no doubt extreme and unrealistic to begin with, Hamlet now systematically destroys. Meanness poses as merriment, misogyny as humor. Our memory of ‘Get thee to a nunnery,’ however, elevates the cruelty by transforming it into another of the character’s mysterious spectacles of self-destruction. He who commanded her to leave a corrupt world now calls her to vulgarity and insult. But why? To act out in the presence of his uncomprehending mother the degradations she has visited on him? Because the prince seems at once deliberate and compelled, the sexual badinage during The Mousetrap rises to a peculiar sublimity of spite.

Where to sit? The question leads him inexorably to Ophelia’s vagina:

Queen: Come hither, my dear Hamlet, sit by me.

Hamlet: No, good mother, here’s metal more attractive. [Turns to Ophelia]

Polonius: [aside to the King] O ho! do you mark that?

Hamlet: [lying down at Ophelia’s feet] Lady, shall I lie in your lap?

Ophelia: No, my lord.

Hamlet: I mean, my head upon your lap.

Ophelia: Aye, my lord.

Hamlet: Do you think I meant country matters?

Ophelia: I think nothing, my Lord.

Hamlet: That’s a fair thought to lie between maids’ legs.

Ophelia: You are merry, my lord.

Hamlet: Who, I?

Ophelia: Aye, my lord.

Hamlet: O God, your only jig-maker. What should a man do but be merry? For look you how cheerfully my mother looks and my father died within’s two hours.

Ophelia: Nay, ‘tis twice two months, my lord.

Hamlet: So long? Nay then, let the devil wear black, for I’ll have a suit of sables. O heavens, die two months ago and not forgotten yet!

Hamlet and Ophelia

Hamlet and Ophelia

The witticism of ‘That’s a fair thought to lie between maids’ legs’ is produced by the idea she might ‘think’ he meant country matters (matters pertaining to the cunt) when asking if he could ‘lie’ on her lap. His strategy is of a piece with much of his mad talk: if you understand me, you in effect reveal a hidden guilt. Ophelia tries to say that she was innocent of the thought of country matters. ‘I think nothing, my lord,’ she maintains, clearly not intending the sexual sense of ‘nothing’, i.e. ‘vagina.’ Yet the word has that sense, and in Hamlet’s equivocating mind her declaration of innocence convicts her.

So, in a little triumph of wit that gathers the strands of ‘think,’ ‘lie,’ and ‘lap’ in a single statement, Hamlet delivers his best line so far. ‘That’s a fair thought to lie between maids’ legs.’ One meaning seems to be: the thought of lying between a maids’ legs is a fair one to me—a forthright declaration of desire. But I cannot believe this the primary sense. It seems unlikely that Hamlet at this point should express a sexual desire for Ophelia so simple and abstract that it might define sexuality itself. The crucial notion is that the thought of ‘nothing’ lies, is somehow located, between maids’ legs. Here is the best I can do: your cunt thinks nothing, which is to say, thinks itself, so that when you think ‘nothing,’ as you just have, you and your cunt are one. In the rejection scene we found the same hesitancy over the location of thoughts concerning sinful women. Does the ‘thought’ of ‘nothing’ lie in Ophelia or Hamlet, woman or man?

Hamlet and Ophelia

Hamlet and Ophelia

Passages of this kind are common enough in Shakespeare. When he is writing in this manner, the very language itself seems under the sway of a universal tendency toward degradation, as words repeatedly find their way to the sexual organs, copulation, pregnancy, venereal disease, prostitution, cuckoldry. Hamlet’s merriment fairly quivers with cynical ferocity. A ‘fair’ thought? We know from the rejection scene what the word ‘fair’ has come to imply: that’s a whorish thought to lie between maids’ legs, corrupting honest chastity. Despite the apparent intimacy of the scene, Ophelia is just an instance of abstract womanhood for Hamlet, a target of taunting insinuations. ‘O God, your only jig-maker.’ How stupid she is, how little she understands! All women think about is nothing! ‘My father died within two hours,’ followed by the halving of ‘twice two months,’ suggests the immediacy for him of the play’s representation. It takes him right back to the adultery, the murder, and the remarriage, a triad of rotten deeds that seem in his memory to have happened virtually at once.

Hamlet is lying down at Ophelia’s feet. His posture has been related both to affected gallantry and tempted virtue. Neither seems quite to fit this particular occasion. Perhaps we should stick to the obvious: he has become half as tall as she, and put his busy mind in proximity to the center of her body. Right next to his brain, as he watches the play and interprets for the rest of the audience, is a woman’s sexual parts. He never forgets it. After the dumb show, which ends with the seduction of the Player Queen, a presenter takes the stage. Ophelia wonders if he will divulge what the show meant. ‘Aye, or any show that you will show him. Be not you ashamed to show, he’ll not shame to tell you what it means.’ ‘Show’ puns on ‘shoe,’ again the vagina: the theatrical show is to reveal the shame of the sexual show, and Hamlet again brings the shame home to the place of feminine sexuality next to his mind.

Hamlet and Ophelia

Hamlet and Ophelia

The entrance of Lucianus carries these allusions to their foreordained end:

Ophelia: You are as good as a chorus, my lord.

Hamlet: I could interpret between you and your love if I could see the puppets dallying.

Ophelia: You are keen, my lord, you are keen.

Hamlet: It would cost you a groaning to take off my edge.

Ophelia: Still better, and worse.

Hamlet: So you mistake your husbands… Begin, murderer.

It would appear to be a turn-on to preside at a festivity demonstrating that your mother is a whore.

Wit first manufactures a sexual life for the virginal Ophelia. If he could see the shameless love acts she normally keeps hidden as he now sees the play before him, he could ‘interpret’ them. Ophelia praises his keen wit. Hamlet then transforms a blade into an erection; it would cost her a groaning, the loss of virginity, to blunt his edge. His wit-thrusts at Ophelia’s vagina have finally adduced a graphic evocation of their copulation. Appreciating all this as a performance in witsmanship, Ophelia is gracious. ‘Still better’ (a better joke), ‘and worse’ (a dirtier and more personal joke, aimed directly at her honor).

Hamlet and Ophelia

Ophelia

Hamlet has a topper: ‘So you mistake your husbands,’ where ‘you’ again means ‘you women.’ In the marriage ceremony husbands are taken ‘for better or for worse,’ but in Hamlet’s misogynistic temperament, mistakenly taken. Wives are false to their vows. ‘Better’ and ‘worse’ returns this wit game to its buried presupposition, Hamlet’s inability to maintain a split image of woman. Even in the women they chose to marry, men get the worse rather than the better. The sequence of witticisms follows the plot of the virgin/whore split with Ophelia in the role of Gertrude: first the thought that Ophelia is having sex with another man; then the thought that he might also possess her; then the thought of betrayed husbands, with wifely falsehood confessed in the ‘better’ and ‘worse’ of the marriage vow. Ophelia’s innocent words enter the channels of Hamlet’s soiled brain and re-emerge in degraded images.

Clearly Sister Ophelia was not a feminine ideal with much future. If she can find entertainment in these insults, so be it. Catching the conscience of the king is no doubt the serious business here, the job the genre demands; but as he waits for that moment Hamlet’s great pleasure is to act as debunking chorus to the dumb shows, puppet shows, and tragedies of female falseness. Ophelia will do in that kind.

Ophelia drowned

Rhodri Lewis, Hamlet and the Vision of Darkness

William Kerrigan, Hamlet’s Perfection

Kenneth Branagh, Hamlet, DVD

HAMLET AND OPHELIA IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

James Sant, Ophelia

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 8

The cat jumps off the bed; under the table, it rubs itself on my legs. Anna, her back against the headboard, draws up her legs and hugs her knees.

̶ Snúlli likes you, Sprague. It’s rare she’s affectionate with anyone but me.

She smiles into my eyes: Her gaze is disquieting, there’s an aware sexuality in her charm. I open the box: In one photo after another, in subdued Kodachrome colours, Anna and Gudrun take turns to play the drowned Ophelia: Now submerged in a stream, flower-strewn hair and long white dress flowing in the grassy current, now floating in reedy water, eyes and hands open to heaven, they perform variations on the Pre-Raphaelite ideal of femininity. As I study the images, Anna studies her face in a hand mirror.

̶ They’re really lovely, Anna.

̶ Do you like them?

She takes off her cardigan.

̶ Yes, very much.

With consummate skill she’s captured all the tropes of the romantic myth: still water as a call from the deep, reality yielding to dream, death as sleep.

̶ You’ve mastered light on water, Anna.

̶ You mean I know how to use a polarizing filter.

̶ And the flowers are very well arranged.

̶ Flowers! Snúlli, come!

The cat jumps onto the bed; Anna stretches out her legs and places the animal in her lap. So this is how you manage the ambiguities of adolescence, this is how you cope with its contradictions: Stroking the cat in your lap while Ophelia preserves your innocence, her death arresting you in childhood. Yes, you’ve staged things beautifully; you’ve realized your fantasy of a pure sexuality, a sexuality without the sex: The dead Ophelia, your second twin, never having become a woman, saves you from the violence of becoming one. But your photos are out of date, they don’t fool me: I know that though you be fifteen, you are impatient for deflowering—I can tell by how you blossom in my presence.

̶ Can I make a photo with you, Sprague?

̶ Sure.

She lifts Snúlli from her lap and places her on the bed. The cat jumps off and runs out of the room.

̶ It’s for my diary. Let’s go next door.

Odilon Redon, The Death of Ophelia, 1905

William Morris Hunt, Hamlet, c.1864

Before the backdrop in the bare room I stand. Anna turns on the lights, looks through the lens, then adjusts the reflectors.

̶ It’s perfect you’re in black. You’re going to play Hamlet.

̶ Oh, really?

̶ Yes. Here, hold Ophelia.

She hands me a blow-up of herself, half-submerged among floating flowers.

̶ Hold it level at your waist.

I do so. She looks through the lens.

̶ No. With your black top we can’t see how long your hair is. Hamlet has to have long hair. Take off your shirt, please.

̶ I say we will have no more marriages.

̶ What?

I pull my Polo over my head and toss it onto a chair.

̶ Those that are married already—all but one—shall live; the rest shall keep as they are. To a nunnery, go.

̶ I’m not going anywhere. Tilt Ophelia up a touch.

̶ Do you have a filter to get rid of the reflection?

̶ Of course. That’s good. Keep that ‘to a nunnery’ expression. Good.

She takes the shot, and another, and another.

̶ Take off your socks.

I take off my socks. She studies me.

̶ Your green eyes are beautiful, Sprague, but they might be deceiving. Hold Ophelia like a mask to your face.

I do so.

̶ Your belt’s perfect. I like the buckle.

She takes the shot, and another, and another.

̶ Thank you.

She turns off the lights.

̶ Now let’s go and see what Gudrun and Marietta are getting up to!

Manet, Portrait of Faure as Hamlet, 1876-77