The Tempest | Pericles

FATHERS AND DAUGHTERS IN SHAKESPEARE: THE TEMPEST

A Jungian Reading by Diane Elizabeth Dreher

All images are from Julie Taymor’s film of The Tempest, in which Prospero is played by a woman, Helen Mirren.

From Diane Elizabeth Dreher, Domination and Defiance: Fathers and Daughters in Shakespeare (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1986) pp. 157-163.

In The Tempest, Shakespeare’s final play, the themes of domination and defiance, integration and personal growth, are brought to conclusion. The play opens with a storm, figuring the destructive power of unintegrated forces within the human psyche. This storm has been staged by Prospero, who has overcome his own violent tempests and will bring comic reconciliation out of potential tragedy. With grace and wisdom, Prospero overcomes two tragic situations: first his own usurpation, from which he had been miraculously preserved, and second, the temptation to turn the play into a revenger’s tragedy by punishing his brother and Alonso. Able to overcome violent tendencies within himself, Prospero can meet the threat of violence from others, preventing the murder of Alonso and quenching the rebellion of Caliban, Stephano, and Trinculo, which offers a parodic parallel to the initial usurpation.

Helen Mirren as Prospero, The Tempest, Julie Taymor, 2010

Prospero, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

The usurpation contains the familiar tragic elements of greed and ambition that reap their fatal consequences in Hamlet and Macbeth. Preserved from drowning and brought to this island, Prospero sees his exile as both a trial and a blessing. He recognizes that his own imbalance was partly responsible for his loss. Excessively contemplative, Prospero had retreated to his books, casting the cares of government upon his brother ‘and to my state grew stranger, being transported and rapt in secret studies’. He had forgotten the necessity of balance. Neglecting his duty, he ‘awak’d an evil nature’ in his brother, providing the occasion for Antonio’s ambition. In his narration to Miranda, he acknowledges his error, a vital step in the process of regeneration, which leads him from the bitterness of revenge to wholeness, integration, and mercy.

Prospero, when expelled from his dukedom, was a narrow and partial man. His twelve years on the island have forced him to balance his retiring and contemplative nature with pragmatism, his excessive intellectualism with emotion, in the care of his daughter, Miranda. The consequences of Prospero’s imbalance were also the cure. Alone on the island without servants, with a two-year-old child on his hands, Prospero was forced to become more responsible. This contemplative scholar had to provide for the daily needs of himself and his young daughter. The demands of daily existence have been, paradoxically, a spiritual exercise, developing the pragmatic, active side of his nature he had heretofore neglected. He has had his books as well, thanks to the kindness of Gonzalo, but has been forced by necessity to divide his labors between the active and the contemplative, moving toward internal balance.

Prospero and Felicity Jones as Miranda, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Prospero and Miranda, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Caring for Miranda has been more than an exercise in pragmatism. She has helped balance his excessive intellectualism with warmth and human caring, leading to the strength of mind and heart that constitutes a healthy human being. A helpless, loving child, Miranda has awakened the nurturing tendencies in Prospero, giving his life another level of meaning. In his words:

A cherubin

Thou wast that did preserve me. Thou didst smile,

Infused with a fortitude from heaven,

When I have deck’d the sea with drops full salt,

Under my burthen groan’d; which rais’d in me

An undergoing stomach, to bear up

Against what should ensue. [I.ii.152-58]

She has been a source of emotional sustenance. Responding to her goodness, love, and wonder, he has become deeper and wiser. While educating Miranda, he has educated his own emotional nature, developing the anima, which has made him a great magus.

We find Miranda at the beginning of the play in a familiar position for Shakespeare’s daughters. A young woman on the threshold of moral maturity, she is ready to leave behind her childhood obedience and strong filial bond for the adult commitment to love and intimacy. Some see Miranda as an innocent, obedient young woman dutifully married off by her father, a throwback to traditional womanhood and the dramatic counterpart of Princess Elizabeth, for whose marriage this play was performed in 1613. But Miranda is more than a beautiful pawn in the larger game of courtship and reconciliation. Although her character is barely sketched, there are touches of spirit, humor, and conflict. Miranda, for all her innocence, is warmly human, a young woman who thinks for herself. In her defense of Ferdinand, her unauthorized visit, and the revelation of her name, Miranda has the spark of Shakespeare’s comic daughters who defy their fathers for love. Although Prospero’s domination is feigned, Miranda’s loving defiance is very real.

Miranda and Ferdinand, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Reeve Carney as Ferdinand, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Prospero’s domination of Miranda has troubled some critics. Coleridge observed that his ‘interruption of the courtship has often seemed to me to have no sufficient motive.’ But Shakespeare provides us with a motive in the text. Like Simonides, Prospero reveals the reason for his behavior in an aside:

At the first sight

They are both in either’s pow’rs; but this swift business

I must uneasy make, lest too light winning

Make the prize light. [I.ii.440-41;449-51]

Prospero simulates the behavior of a senex iratus, placing obstacles between his daughter and her love. He calls Ferdinand a traitor, a spy, and a usurper, taking the young prince captive and subjecting him to the indignity of manual labor. In the role of alazon [a stock character in ancient Greek comedy characterized by arrogance, misplaced self-confidence, and a failure to recognize irony], he exerts a tyrannical authority against which the young couple will strengthen their love and commitment.

Miranda disobeys her father, choosing romantic love over filial obedience. She offers to carry logs for Ferdinand, and in the tradition of Shakespeare’s comic women, proposes to him. The young couple make their vows, having achieved commitment and personal growth. Heretofore an obedient young woman, Miranda asserts herself to claim her love, and Ferdinand, a young prince accustomed to privilege, humbles himself to earn Miranda, realizing ‘for your sake am I this patient log-man’.

Miranda and Ferdinand, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Prospero, Miranda and Ferdinand, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Forced to perform the labor of Caliban to earn his love, Ferdinand must also tame the Caliban, or unruly passions, within himself. Prospero’s imposition of authority upon the young couple is an educational process that disciplines their passions, channeling them within the bonds of conjugal love. The father’s tyrannical behavior provides the thesis, romantic passion the antithesis, synthesized in the commitment of marriage. Ferdinand finds in such love a greater liberty: ‘with a heart as willing as bondage e’er of freedom: here’s my hand’.

Satisfied with Ferdinand’s response, Prospero releases him from bondage and joins the couple in formal betrothal, telling the young prince that:

All thy vexations

Were but trials of thy love, and thou

Hast strangely stood the test: here, afore Heaven,

I ratify this my rich gift. [IV.i.5-8]

Prospero acknowledges his love for Miranda, at the same time releasing her from his care. He tells Ferdinand:

If I have too austerely punish’d you,

Your compensation makes amends, for I

Have given you here a third of my own life,

Or that for which I live; who once again

I tender to thy hand. [IV.i.1-5]

Prospero warns Ferdinand repeatedly not to anticipate marriage by bedding Miranda ‘before all sanctimonious ceremonies’. Many have found his insistence excessive, indicative of unresolved passions and reluctance to release his much-loved daughter to the embraces of another man.

Miranda and Ferdinand, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Miranda and Ferdinand, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Some see Prospero’s warning as a reflection of the father’s obsession with lust and the threat of rape of his daughter. In Prospero’s insistence, however, can be seen a strong belief in balance: the integration of reason and passion, the necessity of love within order. Prospero’s advice reflects a deep metaphysical lesson: the necessity of discipline, faith, and humility in order to embrace a higher truth. Like the earlier romances, The Tempest portrays life as a spiritual exercise: the initiation of the individual into the higher order of love and grace.

In other plays, a Desdemona must hurt her father in order to please her lover, an Ophelia must hurt her lover in order to please her father. Only in two final romances is a daughter spared the tragic dilemma of domination or defiance. The father-daughter relationship is ordinarily permeated with possessiveness, pain, and difficult choices. It is Miranda’s good fortune to have a father who transcends the desire to possess and dominate. He loves Miranda—she is a third of his life—and yet he releases her. Having attained a hermetic balance within himself, he acknowledges her need for growth and development as well.

Prospero and Miranda, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Prospero, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

The Tempest ends, as do many of Shakespeare’s comedies, on a note of marriage and reconciliation. But the harmony of the romances springs from a deeper source than married love. In The Tempest happiness comes not because Ferdinand and Miranda love each other, but because Prospero loves in a different and larger sense. We see Miranda and Ferdinand through a father’s eyes. They appear to us as children, moving in a kind of subdued light of tenderness and compassion. The core of the drama is not the struggles and raptures of young lovers as in Shakespeare’s comedies and love tragedies. Paternal love informs the romances. We are led to see the world through a father’s eyes, following the struggles of the paternal protagonist as he faces the developmental challenges of middle life. He accepts his own sexuality and fatherhood, develops a nurturing love for his daughter and then releases her to seek her own commitments. In these final plays, Shakespeare’s fathers discover a means of expressing care, reconciling the misdirected forces of eros into benevolent caritas.

The reconciliation in this play has been called disturbing and incomplete, for unlike Leontes and Pericles, Prospero is not reunited with his wife. The difference is significant. In a developmental sense, Prospero is Shakespeare’s oldest father, ready to face the final challenge of his life. His missing wife represents no deficiency, but an incorporation of the feminine element within himself. Having been ‘both father and mother to Miranda,’ he is in touch with his anima, which enables him to release his daughter to her destiny instead of possessively clinging to her. He has achieved individuation, a creative androgyny that makes his magic possible.

Prospero, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Djimon Hounsou as Caliban, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

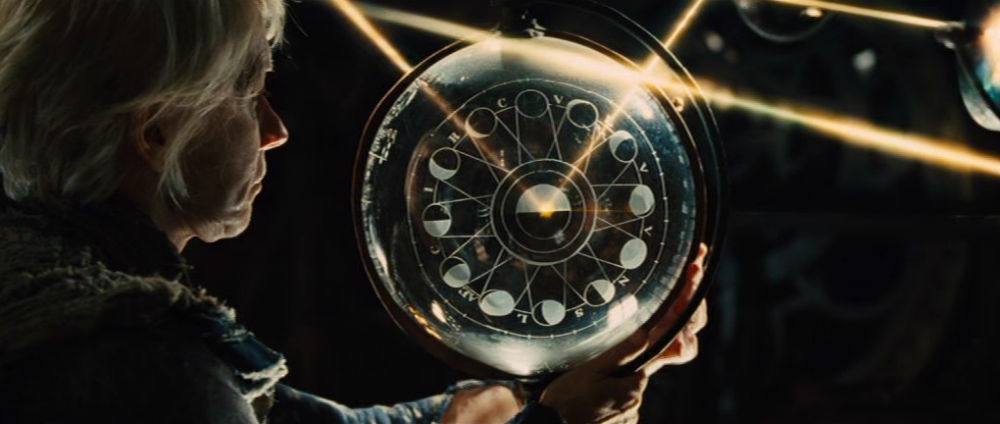

Many have recognized that Ariel and Caliban represent opposing forces within Prospero and the twin potentialities of the human spirit. They can be seen as the mental and physical sides of his nature. Earlier in his life, Prospero had been excessively intellectual, unable to express his feelings or recognize the negative passions growing in his brother. But caring for Miranda has actualized his benevolent emotions. Similarly, in contending with Caliban, he has recognized the reality of the shadow and the primitive urges he represents. He tells Miranda that Caliban must be controlled, but cannot be denied: ‘We cannot miss him: he does make our fire, fetch in our wood and serves in offices that profit us’. In Renaissance natural philosophy, Caliban corresponds to the vegetative and animal soul. He performs physical functions such as making the fire, and embodies the senses and passions. In contrast, Ariel, a spirit without a body, represents the rational soul. In Milan, Prospero had buried himself in his books, denying his emotional and physical nature. At the end of the play, however, he claims Caliban as his own: ‘this thing of darkness I acknowledge mine’.

Prospero’s reconciliation of the opposites within himself—body and soul, unconscious and conscious, masculine and feminine—produces a hermetic balance that gives him his power. The integration of his anima has developed his compassion, enabling him to reject the temptations of revenge and turn justice into mercy. Prospero’s compassion is evident as early as I.ii, when he commends Miranda for pitying the shipwrecked strangers and assures her that there’s ‘no harm done’. When Ariel describes Alonso’s repentance and the shipwreck victims’ collective misery—’Your charm so strongly works ’em that if you now beheld them, your affections would become tender’—Prospero answers that ‘mine shall’, proclaiming that ‘the rarer action is in virtue than in vengeance’. He forgives them one and all, while recognizing the unregenerate state of Antonio and Sebastian. Keeping his eye on his reprobate brother, Prospero transcends any personal resentment, attaining the wisdom of detachment.

Ben Whishaw as Ariel, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Prospero, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

In the final scenes, Prospero renounces his magic, announcing that in Milan he will oversee the marriage of Ferdinand and Miranda and take up his duties as duke, while ‘every third thought shall be my grave’. Some people are troubled by this line, but the meaning is clear in the context of personal development. His magic has been a means to a greater end. It is spiritual alchemy, performed to produce the quintessence within the individual, the perfect balance that constitutes the integrated soul. Once this has been achieved, the means are no longer necessary. Prospero’s hermetic magic has reconciled the conflicting forces within him and reunited Naples and Milan. His final challenge is to return to Milan, where he will reign as duke, balancing action and contemplation.

In The Tempest, all is not resolved into perfect harmony. The realities of the fallen world are still evident in those reprobate members of humankind who will not repent. This play does not offer the easy assurance and miraculous conversions of Shakespeare’s festive comedies. Aware of political realities, Prospero will spend two-thirds of the time in strict vigilance, exercising his duties as duke. ‘Every third thought’ will be devoted to a more personal responsibility. In the memento mori tradition, he will confront for himself the final crisis of integrity.

Prospero, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Prospero, The Tempest, Julie Taymor

Prospero, like Lear, is an old man who faces the final developmental crisis, the confrontation with death. While Lear’s internal conflicts reduce him to folly and impotence, Prospero faces this final challenge with wisdom and faith, the detached and yet active concern with life itself in the face of death itself, which overcomes the temptation to despair and the dread of ultimate non-being. He has managed to combine his conflicting tendencies into a vision which affirms his faith, worth, and the value of life itself. Having achieved the state of grace in personal integration, he can look beyond this life to the promise of heaven, his developmental journey and spiritual pilgrimage complete.

FATHERS AND DAUGHTERS IN SHAKESPEARE: PERICLES, PRINCE OF TYRE

A Jungian Reading by Diane Elizabeth Dreher

All images are from the BBC production of Pericles, Prince of Tyre (1984), directed by David Hugh Jones.

From Diane Elizabeth Dreher, Domination and Defiance: Fathers and Daughters in Shakespeare (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1986) pp. 146-150.

Shakespeare’s romances are filled with incest and misogyny, reflecting the protagonists’ lack of integration. While incest lies beneath the surface in many of his father-daughter relationships, it confronts us directly in Pericles. In Act I, when young Prince Pericles courts the beautiful daughter of Antiochus, he is faced with the shocking specter of father-daughter incest. As the riddle reveals, this young woman to whom he has been so strongly attracted is a ‘glorious casket stor’d with ill’. The trials of Pericles and the ensuing action of the play flow from this primal threat to family and social structure. Pericles leaves Antioch abruptly, going on a long journey to avoid the wrath of Antiochus. Throughout his wanderings he carries with him an underlying suspicion of women and sexuality. In Antioch Pericles has concentrated the malefic anima and found a father who possessed his own child, succumbing to those dark paternal passions hinted at in Hamlet, Othello and Lear. In his journey through life, Pericles must choose for himself between images of the Good Father and the Bad Father and recognize the two sides of the anima. Repelled by the malefic and seductive anima he finds in Antioch, Pericles loses sight of the benevolent alternative until he is redeemed by his daughter Marina.

Antiochus and his daughter

Pericles and the fishermen

Pericles is washed ashore in Pentapolis after a great storm—tempests abound in Shakespeare’s romances, symbolic of unresolved psychic energies. His father’s armor, his patrimony, is retrieved by helpful fishermen. With his active male persona, his conscious self, Pericles has no difficulty. As his successful battle in II.ii demonstrates, he is in touch with his masculinity, like his father performing noble deeds.

It is his unconscious, his anima, with which Pericles must come to terms. He meets the Good Father in Simonides, the first such good father in all Shakespeare. Wise and balanced, Simonides has achieved that final integration psychologists have written about. Recognizing his part in the cycle of human development, Simonides has overcome the desire to dominate or possess his daughter. No Lear, Brabantio or stubborn Egeus, he releases her to the man she loves.

Thaisa and Simonides

Thaisa, Simonides, Pericles

With a wisdom beyond ego, he recognizes in Pericles a valiant young man worthy of his daughter and applauds her choice, unthreatened either by a younger rival for his daughter’s affection or by her assertiveness:

Now to my daughter’s letter:

She tells me here, she’ll wed the stranger knight,

Or never more to view nor day nor light,

‘Tis well, mistress; Your choice agrees with mine;

I like that well: nay, how absolute she’s in it,

Not minding whether I dislike or no!

Well, I do commend her choice;

And will no longer have it be delay’d,

Soft! here he comes: I must dissemble it. [II.v.15-23]

Simonides takes upon himself the role of senex iratus to test his future son-in-law and strengthen the bond between the young lovers. This trial allows for the ritual transfer of his daughter’s loyalty from father to husband.

Not all is resolved for Pericles, however. As Thaisa becomes pregnant, bringing him to the brink of paternity, everything suddenly goes awry. Antiochus is dead, and Pericles must return to his own kingdom in Tyre. On board ship his pregnant wife falls into labor, and Pericles finds himself in the grip of natural forces he cannot control. He cries out to the storm, to Lucina, goddess of childbirth, to all these mysterious forces beyond his comprehension.

Pericles

Pericles, Marina in swaddling clothes, Lychorida

Only in the romances is a female character represented as pregnant and going through childbirth. Both here and in The Winter’s Tale the male protagonist is alienated from his queen, at least in part by the mystery of gestation, and loses both wife and child until a later rebirth and reunion. Pericles errs in his imbalance, his fear of the irrational feminine mysteries to which he cannot relate. He is courageous in combat, but in III.i.1-14 he walks the deck, crying out to the gods to allay the fierceness of the storm and his wife’s labor, remaining far removed from the scene of childbirth. Apparently, he would rather confront the storm than comfort his wife. Beset by the throes of childbirth, Thaisa has become for him an alien ‘other,’ best left to Lychorida, another woman, to cope with these fleshly mysteries.

When Lychorida emerges with the infant, reporting his wife’s death, she repeatedly counsels ‘patience’.

But Pericles is hardly patient. He hastily accedes to the demands of the sailors for whom this woman on board is taboo, failing to realize that Thaisa is still sufficiently alive to be revived by Cerimon many hours later. Dominated by his fears, Pericles casts away his dearly loved wife, who has become for him a symbol of the fleshly mysteries of birth and death.

Thaisa, Marina, Lychordia and Pericles

Cleon, Dioniza, Marina and Pericles

Just as suddenly he casts his daughter from him at Tarsus. Initially the child needs a wet nurse, but he leaves her there as though there were no opportunities for her upbringing in his own country. Recoiling from the responsibilities of parenthood, Pericles casts aside these images of birth and death, renouncing his feminine side completely. He withdraws in self-imposed mourning, vowing not to cut his hair until his daughter marries, and once again affirms life.

Years later, believing her dead, he retreats still further, going to sea, renouncing his emotions, and falling into catatonia. Tossed about by the sea, symbolic of the unconscious, Pericles’ physical condition mirrors his psychological state.

Pericles

Marina and Lysicmachus

His daughter, Marina, represents the very virtue he lacks. She overcomes adversity patiently, in marked contrast to her despairing father. In her radiant innocence she reforms even the men in the brothel, by appealing to their higher nature, touching the benevolent anima in each of them. Reunited with Pericles, she offers beauty, renewal, and hope. She touches him with emotion, revives him, and restores his identity.

Her story sounds like a riddle, recalling the riddle he heard years ago in Antioch. But the situation is now reversed. Attracted to this lovely girl, who resembles his lost wife, he responds as the Good Father, recognizing the attraction but loving within paternal bounds. Acknowledging his own anima, he can give his daughter in marriage, accepting the mysteries of birth and death from which he had retreated long ago:

O, come hither,

Thou that beget’st him that did thee beget;

Thou that wast born at sea, buried at Tarsus,

And found at sea again! [V.i.196-99]

This time he sees beyond the flesh into a paradoxical pattern of birth and renewal, the irrational mysteries of human life illuminated with the radiant power of the spirit.

Pericles (off-screen) and Marina

Marina, Lysicmachus, Pericles and Thaisa

Pericles no longer fears his own emotions and the natural forces beyond his control. His suffering has prepared him for an enlargement of vision and an act of faith. The conclusion of this play, like those of the other romances, points to a greater harmony for those who find balance within themselves. Pericles’ shattered world is finally restored to order. A vision of the goddess Diana leads him to Ephesus, where he finds his lost Thaisa. She has been revived by Cerimon, who anticipates the more complete portrayal of the magus in Prospero. The romances are filled with theophanies. Gods and goddesses touch this mortal world and reveal the workings of a benevolent providence beyond human understanding. In Pericles, the deity is Diana; in Cymbeline, Jupiter. In The Winter’s Tale, Apollo’s prophecy indicates a supernatural power working behind the scenes, and The Tempest features a masque of benevolent goddesses as well as repeated references to grace and regeneration. Shakespeare’s final plays are replete with visions of divine mercy. Their protagonists grow from inner division and alienation to a state of grace by integrating the opposing forces within into dynamic balance, becoming receptive to a greater harmony.

THE TEMPEST and PERICLES in ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 18

Before we go to the island, however, answer me this, my love: If you are Marina, I’m no governor of Mytilene; if you are Miranda, I’m no Prince of Naples. But if you are Mara, I must be Ariel. Now tell me, Marietta-Prospero, when our story’s told, will I return to the tree or be set free?

The Tempest, South Coast Repertory Theater (California), 2014

Pericles, Theatre for a New Audience, Polonsky Shakespeare Center (New York), 2016

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 2

Prospero and Miranda, Pericles and Marina, the fiction of the island, the world as lasting storm… Motherless daughter?

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 10

I find myself feeling sad at leaving Akureyri. How can I be missing Anna and Gudrun so soon after having left them? I think of Prospero and Miranda, Pericles and Marina; I think of the father I might have been to the daughter we’ll never have. Why do Anna and Gudrun move me so?

The Tempest, South Coast Repertory Theater (California), 2014

Pericles, Theatre for a New Audience, Polonsky Shakespeare Center (New York), 2016

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Two Chapter 1

Mara Marina, Mara Miranda, in light set my feet in your footsteps, at night echo your footfalls in my ear. Open your mouth and breathe on me. Ruah! The wind in my face, with each stride I lay down the bounds of duration: I walk the world. Will you walk with me?

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Two Chapter 3

Mara Marina, Mara Miranda, I hallow my lips in the hollow of your sacrum; in the small of your back I retrieve my boat. Where next, my lover? Between the blonde a glint of blue says, ‘I’m yours to discover’. I hoist the sail and set out to sea, other shores to explore.

Pericles, Theatre for a New Audience, Polonsky Shakespeare Center (New York), 2016