VANESSA REDGRAVE, FILM ACTRESS

CORIOLANUS (FIENNES | SHAKESPEARE)

Richard Jonathan

Ralph Fiennes & Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus

VANESSA REDGRAVE IN ‘CORIOLANUS’: INTRODUCTION

The famous scene where his family pleads with the invincible warrior to spare Rome is a moment of illumination for Coriolanus, where in one and the same movement he decides to spare Rome, which he has betrayed, and to deliver himself to his enemies, who he is betraying. The values with which he identifies to the point of insanity leave him no way out of this dual betrayal and give him a sacrificial fervour, a suicidal identity, and an absolute solitude at the end of which only death remains.

Richard Marienstras, Shakespeare au XXIe siècle: Petite introduction aux tragédies (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 2006) p. 65. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Coriolanus analyzes the obsessively repetitive effect of the Roman belief that the polis and individual character must both be human ‘constructs’, willed against the flux of nature, and the consequent reduction of the ideal of human community to individual competitiveness with its dangers of solipsism and inability to sympathize with others. The resulting tragedy is arguably one of the most profound political analyses in the language, because Rome’s weakness is traced not to later degeneration and vice but to the very characteristics that made Rome great, and the connection between public ethos and private tragedy is for the first time located clearly in the middle ground of family neurosis. … The key relationship in the play is that between Coriolanus and Volumnia.

R.B. Parker, Introduction to Coriolanus (The Oxford Shakespeare, 1994) p.13 and p.21.

Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

The special brilliance of Coriolanus is its insight into the mutual influence of psychology and politics. This involves the way that family relationships shape individual identity, and the dependence of those relationships in their turn on the wider values and expectations of society as encoded in its institutions and its language.

R.B. Parker, Introduction to Coriolanus (The Oxford Shakespeare, 1994) p.43

Gerard Butler as Tullus Aufidius | Ralph Fiennes as Caius Martius Coriolanus

Vanessa Redgrave’s exceptional talent as an actress was first revealed to the theatre-going public in 1961, when, at age 24, she played Rosalind in As You Like It at Stratford. At age 73, in 2010, playing the hero’s mother, Volumnia, in Ralph Fiennes’ film of Coriolanus, she gives a performance that confirms her reputation as an actress touched by grace, capable of bringing forth from the depth of humanity within her the shadings that, in the service of the film, make her character scintillate.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Celebration! That, in my view, is the attitude to adopt in playing Shakespeare, and Redgrave, having grown up with him, celebrates him. Trusting the dramatist, she surrenders herself to the role, despite her initial reservations prompted by her finding Volumnia alien to herself. In contrast, she is totally at home in the dramatist’s language, be it iambic pentameter or prose. In this post, I will analyze Vanessa Redgrave’s acting in the five scenes of Coriolanus in which she appears, elucidating the work’s dramaturgy and themes to the extent that doing so contributes to the analysis of the acting. Note that Shakespeare’s dialogue is given exactly as it is used in the film.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

VANESSA REDGRAVE IN ‘CORIOLANUS’: ACT I SCENE 3

In this first scene, Redgrave is called upon to convey, firstly, Volumnia’s alienation of her individuality in the ideology of Rome; secondly, the ‘co-dependent’, quasi-incestuous nature of her relationship with her son, a relationship governed by the ‘values and expectations’ she has internalized, the ‘institutions and language’ of Rome. To do this, the dramatist has given her a foil in Virgilia, played by Jessica Chastain. ‘Acting means working to be alive and alert to the incident and the moment, to the director, the other actors, and the script,’ Redgrave writes in Vanessa Redgrave: An Autobiography (London: Arrow Books, 1992, p. 51). As Coriolanus’ wife, Chastain glows as she incarnates Virgilia’s ‘ideal of human community’, in contrast to Volumnia’s reduction of it to ‘individual competitiveness’.

VOLUMNIA: I pray you, daughter, sing, or express yourself in a more comfortable sort.

Jessica Chastain & Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

In Volumnia’s first speech, Redgrave’s body-voice makes apparent aspects of the subtext that will be reinforced as the film develops. When she delivers the line, ‘If my son were my husband…’, we suppose that her dead husband no longer lives in her memory and that she probably found no fulfilment in her marriage. We also register that Coriolanus is fatherless, and so unshielded from a mother who does not recoil from ‘psychic incest’. Next, we note that Volumnia places honour and fame above love and sex. She, no longer in sexual circulation, seems to want to suppress the tender dimension of her son’s sexuality and develop only its aggressive aspect, not giving a thought to his wife’s desire. Finally, by the end of the speech, we realize that Volumnia is out-and-out perverse, and has wilfully, with studied determination, shaped her son in her image. That her speech is addressed to Virgilia, her daughter-in-law, makes it all the more terrifying. Throughout, Redgrave’s tone is calm and confiding, contrasting with the substance of her speech; we guess that she is at one with her society, and that society’s values now strike us as suspect.

VOLUMNIA: If my son were my husband, I would more freely rejoice in that absence wherein he won honour than in the embracements of his bed where he would show most love. When yet he was but tender-bodied and the only son of my womb, I, considering how honour would become such a person, was pleased to let him seek danger where he was like to find fame. To a cruel war I sent him, from whence he returned his brows bound with oak.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Here, Virgilia implies that death for an abstraction—honour, fame—is not her ideal: the love of a living husband is far more important to her.

VIRGILIA: But had he died in the business, madam, how then?

Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

In her response to Chastain’s Virgilia, Redgrave delivers Volumnia’s extravagant extolment of dying nobly for one’s country with just a touch of doubt, a crack through which her humanity peeps, making the perversity of her view more poignant. Such playing against the dominant stance of the character, doing so in carefully calibrated doses, is an element of the actor’s art Redgrave employs to great effect in this scene. Note Volumnia’s preference for the public virtue of violent death over the private cultivation of pleasure in sex. If Virgilia could get Coriolanus into her bed more often, would the mother’s son still be so morally absolute? These are the undertones of the conversation that the actresses faces enable us to pick up.

VOLUMNIA: Then his good report should have been my son. Hear me: had I a dozen sons, I had rather eleven die nobly for their country then one voluptuously surfeit out of action.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Virgilia refuses to engage with Volumnia’s ideals: the safety of her husband is her only concern. The real over the ideal, the present over the future, sex over war: these are her values. She upholds them in silence, but the quality of her presence speaks.

VIRGILIA: Heavens bless my lord from fell Aufidius!

Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Blood over milk, soldiering over loving, Rome over the individual: these are Volumnia’s values, and in asserting them, Redgrave has to guard against caricature. She does so by keeping an open-faced demeanour, ‘normalizing Volumnia’s perversity by playing the scene straight. The effect is terrifying.

VOLUMNIA: He’ll beat Aufidius’ head below his knee and tread upon his neck. Methinks I hear hither your husband’s drum. I see him stamp thus; and cry thus: ‘Come on, your cowards! You were got in fear though you were born in Rome.’ His bloody brow then wiping forth he goes.

VIRGILIA: His bloody brow? O Jupiter, no blood!

VOLUMNIA: Away, you fool! It more becomes a man than gold his trophy.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

VANESSA REDGRAVE IN ‘CORIOLANUS’: ACT II SCENE 1

This scene opens with Volumnia reciting an incantation, vaguely reminiscent of the witches in Macbeth. It is more a consecration of the present moment, however, than a prognostication. In tight close-up, Redgrave delivers the verse in a whisper, augmenting the eerie effect. Somewhat awestruck at this ceremony honouring her son, she conveys motherly pride in his seemingly magical ability to dispense death, god-like, with impunity.

VOLUMNIA: Before him he carries noise, and behind him he leaves tears. Death, that dark spirit, in his nervy arm doth lie, which being advanced, declines; and then men die.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

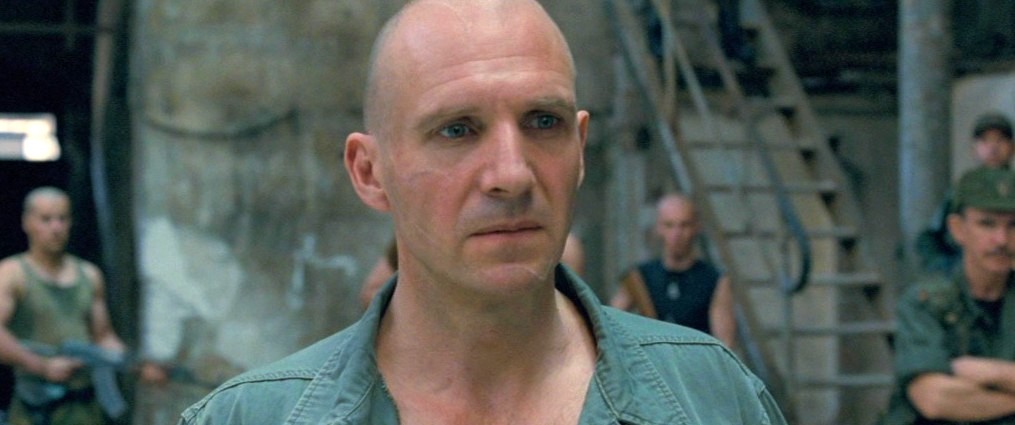

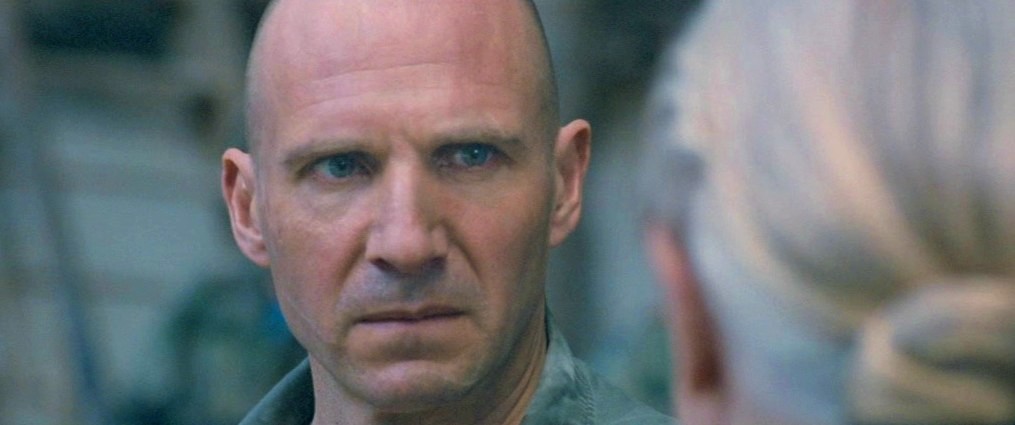

Ralph Fiennes, as Caius Martius Coriolanus, conveys at once the moral absolutism of a man ‘constructed’ on Roman ideals and the toxic fusional bond of a child with his mother. The hate necessary to free himself from her is never expressed in their relations; instead, it is acted-out in his actions elsewhere. She is his creator, he her creature, and as long as he submits to her will, a semblance of love and respect will prevail.

CORIOLANUS: You have, I know, petitioned all the gods for my prosperity.

Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

In the midst of the multitude saluting her son, Volumnia carves, with Coriolanus, a private space out of the public one, a bubble of intimacy in which they renew their complicity. The radiant joy Redgrave shows here will serve as a foil for the anger that lies in store; the expansiveness of her expression will contrast with the constriction to come. Uniformed at the ceremony but with official faces on pause, mother and son convey the interpenetration of state and family politics. Note that even in this moment of intimacy, the mother’s discourse is rife with ascriptions—‘good’, ‘gentle’, ‘worthy’, ‘honour’—rather than anything inner-directed. Is it any wonder her son is a hollow man? Irony is knit into the fabric of Coriolanus, and to convey it, Redgrave knows she has to play things straight.

VOLUMNIA: Nay, my good soldier, up. Ah, my gentle Martius, worthy Caius, and, by deed-achieving honour newly named—What is it?—’Coriolanus’ must I call thee?

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

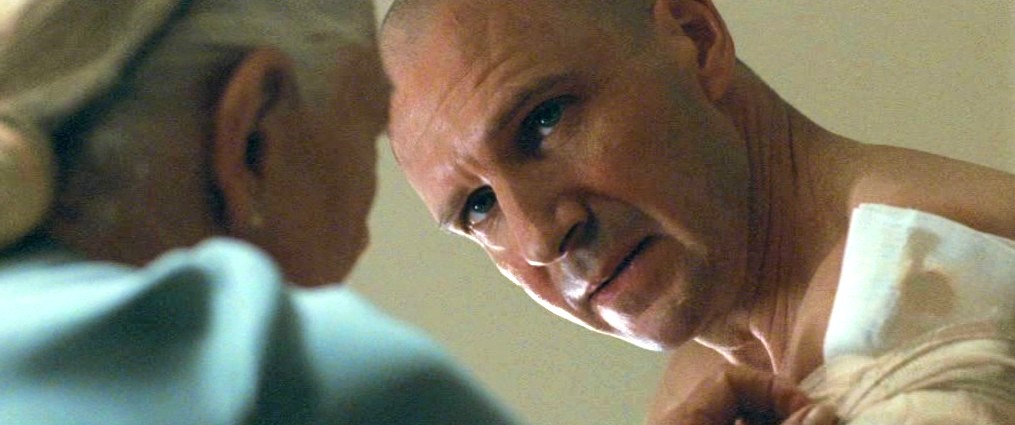

From ceremonial splendour the mother-son duet shifts to an everyday room in the house they share. Coriolanus confides his cares to Volumnia as tenderly she dresses his wounds. Redgrave again is called upon to convey the calculating in the altruistic: binding his wounds, she is binding him to her. Indeed, while his only concern is to preserve his vitality, hers is to promote his social ascension. Implicitly acknowledging her plans for him, he reluctantly eases himself into the game.

CORIOLANUS: The good senators must be visited, from whom I have received not only greetings, but with them change of honours.

Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

Volumnia then cuts to the chase with Coriolanus: his ‘change of honours’ is her wish fulfilled; his path to power, now open, is her ‘fancy’ made flesh. The ‘one thing wanting’ is for Rome to make her son consul. In a gentler register than that of Lady Macbeth, Volumnia must spur Coriolanus’ ambition in order to vicariously realize her own. For Redgrave, the task at hand is to apply the spur without making the horse baulk, so to speak; she achieves this by dosing her diction to the unfurling of the bandage, and becomes mother-wife seducing son-husband.

VOLUMNIA: I have lived to see inherited my very wishes, and the buildings of my fancy. Only there’s one thing wanting, which I doubt not but our Rome will cast upon thee.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

The horse, however, does baulk: Coriolanus, in his dressage-to-the-death with Volumnia, declares he will not go along with convention. To that, Volumnia, knowing that compromise is not part of Coriolanus’ vocabulary, will respond later; for now, she is content to recognize that her ‘long game’ of persuasion and manipulation, fashioning her son, has a little longer to run.

CORIOLANUS: Good mother, I had rather be their servant in my way than sway with them in theirs.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

The scene closes with Virgilia appearing in the doorway, vaguely aware that her role has been usurped by Volumnia. If not the odour of incest, she does get a whiff of conspiratorial intimacy: thick as thieves, mother and son exclude wife and daughter-in-law. The silence of Redgrave and Fiennes, here, speaks volumes.

Vanessa Redgrave, Ralph Fiennes, Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus

VANESSA REDGRAVE IN ‘CORIOLANUS’: ACT III SCENE 2

Protesting against the urgings of the patricians to apologize to the citizens for insulting them, and, moreover, to go out and display his wounds by way of winning their votes, Coriolanus throws a temper tantrum. What he is really railing against, of course, is his mother’s sway over him. Indeed, he knows that because he is so deeply entwined with her, the psychic work required to disentangle himself would overwhelm him. He knows that his resistance will always be token, for true resistance would oblige him, in order to reconstruct himself on a detoxicated footing, to return, at least momentarily, to the state of vulnerable infancy. The courage required to do that is greater than the courage it takes to kill: confronting a fierce external enemy is easier than confronting the helpless child within. Like a moth to the flame, however, Coriolanus always returns to his mother, musing, in the midst of his tantrum, that she does not approve of him. How will Vanessa Redgrave’s Volumnia respond?

CORIOLANUS: Let them pull all about mine ears, present me death on the wheel or at wild horses heels, yet will I still be thus to them.

VIRGILIA: Martius!

CORIOLANUS: I muse my mother does not approve me further— I talk of you. Why would you wish me milder? Would you have me false to my nature? Rather say I play the man I am.

Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

Into Volumnia’s disapproval, Redgrave injects a dose of stern tenderness. She knows her son is better at kicking ass than kissing it, but to become consul, he must stoop to conquer. Her demeanour in this scene shows her to be a fine tactician; like an adult with an agenda dealing with an unruly adolescent, she plays the sequence as a series of chess moves. In her first two lines here, she offers the hard man of action insights into the soft dimension of his situation, and in her third line, she contents herself with humouring him. We must always remember, however, that in Coriolanus, the tragic flaw is not in the son alone, but in the mother-son duo. Indeed, Volumnia’s internalization of Roman ideals (heroism, patriotism, honour) and her pursuit of them via her son blind her to the fact that the domain of the ‘soft’ (emotions, politics, ambivalence) represents, for Coriolanus, an existential threat. Why? Because the skills he would gain by engaging in politics, developing emotional intelligence and learning to cope with ambivalence would set him on the slippery slope of disentangling himself from his mother. And, as we’ve seen, the child hiding behind his hardness is more to be feared than ‘fell Aufidius’. The ‘straightness’, then, with which Redgrave plays Volumnia’s blindness to Coriolanus’ needs serves to highlight the tragic flaw at the heart of this duo.

VOLUMNIA: Sir, sir, I would have had you put your power well on before you had worn it out.

CORIOLANUS: Let go.

VOLUMNIA: You might have been enough the man you are with striving less to be so.

CORIOLANUS: Let them hang.

VOLUMNIA: Ay, and burn too.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Solipsistic Coriolanus, because he will not allow himself to be vulnerable, cannot learn to trust; he therefore will not, as Volumnia requests, ‘be counselled’. She lets the other patricians, Menenius and Cominius, speak, but she knows she alone can get through to her son. And so she slips into the role of dispenser of practical wisdom. Lesson number one: Have your brain use your heart to achieve your ends; don’t let your heart sabotage you. At this stage of the struggle, choosing reason as her weapon, she confronts him face-to-face. There’s a touch of frailty in Redgrave’s hardness and an incisive intelligence in Shakespeare’s words: the body-voice of the actress expresses the two to great effect.

MENENIUS: Come, come, you have been too rough, something too rough. You must return and mend it.

COMINIUS: There’s no remedy, unless by not so doing, our good city cleave in the midst and perish.

VOLUMNIA: Pray, be counselled. I have a heart as little apt as yours, but yet a brain that leads my use of anger to better vantage.

MENENIUS: Well said, noble woman.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Now, with the intimacy of her arm around his shoulder, Redgrave’s Volumnia draws Coriolanus aside and begins to explain, concretely, just what she means when she said, ‘You are too absolute’. This word—‘absolute’—is a key one, for in employing it, Volumnia shows that, despite the perversity of her entanglement with her son, she still retains a certain critical distance (unlike Lady Macbeth, Volumnia will not go mad). What she does not understand, however, is that it precisely because Coriolanus cannot say ‘No’ to her that he must say ‘No’ to everybody else. Moreover, she fails to grasp that her son’s moral absolutism is akin to that of the televangelist raving against adultery after having had a quick one with his neighbour’s wife: He is being high-minded about his own hang-ups, playing out in the social sphere his personal conflicts. For Coriolanus, any concession risks self-questioning; any stepping down risks self-destruction. Unaware of any of this, Volumnia proceeds to lesson number two: high-mindedness and back-handedness (‘honour and policy’) grow together like friends in war. To deliver the line, Redgrave adopts a conspiratorial tone, emphasizing that mother and son, despite the public business they are undertaking, operate in their own private sphere.

CORIOLANUS: And what must I do?

MENENIUS: Return to the tribunes.

CORIOLANUS: What then, what then?

MENENIUS: Repent what you have spoke.

CORIOLANUS: For them? I cannot do it to the gods, must I then do it to them?

VOLUMNIA: You are too absolute. I’ve heard you say that honour and policy, like unsevered friends in war, do grow together.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Question: ‘How do you know when a lawyer is lying?’ Answer: ‘When his lips are moving.’ If politicians, on the scale of liars, are a notch or two down from lawyers, the two are fundamentally of the same stripe. The reason politicians lie, as Coriolanus repeatedly points out, is because their constituents cannot bear the truth. Knowing her son’s absolutism makes him refractory to the art of lying, Volumnia nevertheless proceeds to lesson number three: Tell the people what they want to hear, not what you believe to be true. Lying is honourable if it achieves noble ends. For your rudeness to the people give as excuse that, since you are a soldier, your sword does the talking, hence the infelicities of your unpracticed tongue. Finally, say you’ve turned a new leaf, and in your book they, the people, are now number one. Redgrave delivers the message unsalted by cynicism; riding neither the high horse nor the rocking one, she construes the words as self-evident wisdom.

CORIOLANUS: Why force you this?

VOLUMNIA: Because that now it lies you on to speak to the people; not by your own instruction, nor by the matter your heart prompts you, but with such words that are but roted in your tongue, though but bastards and syllables of no allowance to your bosom’s truth. I would dissemble with my nature where my fortune and my friends at stake required I should do so in honour. I am in this your wife, your son, the senators, the nobles, and you. I prithee now, my son, go to them, be with them, say to them thou art their soldier, and, being bred in broils, hast not the soft way in asking their good loves; but thou will frame thyself, forsooth, hereafter theirs.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Coriolanus, however, will not play ball: he is too absolute. Volumnia tries to forestall his refusal with her peremptory, ‘He must, he will [obey]’. As a concession to his dignity, she requests his assent, and orders him to act on it. He then launches into a tirade, apparently resigning himself to carrying out the patricians’ wishes, but then, touched to the quick by his own invective, he declares he will not debase himself, he will not ‘cease to honour his own truth’, by playing the politician. Listening, Redgrave’s Volumnia stands eye-to-eye before him, steadfast. The quality of an actor’s listening to his fellow actors is, of course, part of the actor’s art: while Redgrave is all ears, it is her face that does the talking.

MENENIUS: This but done even as she speaks, why, their hearts were yours.

VOLUMNIA: I prithee, go and be ruled.

COMINIUS: Sir, it is fit you make strong party, or defend yourself by calmness or by absence. All’s in anger.

MENENIUS: Only fair speech.

COMINIUS: I think it will serve, if he can thereto frame his spirit.

VOLUMNIA: He must, he will. Prithee now, say you will, and go about it.

CORIOLANUS: Must I with base tongue give my noble heart a lie that it must bear? Well, I’ll do it. Away, my disposition; and possess me some harlot’s spirit! A beggar’s tongue make motion through my lips. I will not do it, lest I cease to honour mine own truth, and by my body’s action teach my mind a most inherent baseness.

Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

Redgrave unrelentingly holds Fiennes’s gaze as Volumnia invokes the ideals of Rome she and Coriolanus share—honour, self-sacrifice, courage—while simultaneously suggesting that, in diverging from those ideals (as she sees it, because of his pride and stubbornness), he is creating a rift between the two of them. This, of course, is what Coriolanus most wants—and most fears. To drive home her point, Volumnia grabs an emblem of Roman authority, a flag on its staff, and delivers the line, ‘Thy valiantness was mine, thou suck’st it from me, but owe thy pride thyself’. We can imagine the anger Coriolanus now feels, the sense of not being his own man but having been made by his mother. Moreover, we can imagine, deep within him, a disturbance: the tremor of the repressed impulse to redirect his violence at its rightful target: his mother. Redgrave, with her body-voice, shadows the familiarity of melodrama with the intimation of tragedy: Shakespeare is in her blood.

VOLUMNIA: At thy choice, then! To beg of thee is my more dishonour than thou of them. Come all to ruin. Let thy mother rather feel thy pride than fear thy dangerous stoutness, for I mock at death with as big heart as thou. Do as you like. Thy valiantness was mine, thou suck’st it from me, but owe thy pride thyself.

CORIOLANUS: Pray be content, mother. I am going. Chide me no more. Look, I am going. I’ll return consul, or never trust to what my tongue can do in the way of flattery further.

VOLUMNIA: Do your will.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

VANESSA REDGRAVE IN ‘CORIOLANUS’: ACT IV SCENE 2

In this bravura scene, Volumnia and Virgilia encounter Brutus and Sicinius, the scheming tribunes responsible for Coriolanus’ banishment, and lay into them, both verbally and physically. The pacing of the action here, the arc of discord and resolution, is brilliant. Redgrave gets things rolling with a typical feminine gambit, smiling as she puts a caustic twist on, ‘O, you’re well met!’ before uttering a curse directly in the face of her interlocutor. Uttered in close-up, the choice words hit home.

BRUTUS: Here comes his mother.

SICINIUS: Let’s not meet her. They say she’s mad.

VOLUMNIA: O, you’re well met! The hoarded plague of the gods requite thy love!

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

To Sicinius’ ‘Are you mad?’ Volumnia, using the force of her adversary against him, assuming the hysteria she’s accused of the better to land her punches, responds, ‘Ay, fool. Is that a shame?’. Here, Redgrave’s Volumnia, her hand gripping Sicinius’ shoulder, her face in his face, employs gesture and expression to particularly good effect.

VOLUMNIA: Will you be gone?

VIRGILIA: You shall stay too! I would I had the power to say so to my husband.

SICINIUS: Are you mad?

VOLUMNIA: Ay, fool. Is that a shame?

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Lucid in her anger, Volumnia stacks up Coriolanus’ actions against Sicinius’ words and finds the latter wanting, yet, ironically, she acknowledges the weaker party won because, unlike her son, he knew how to use ‘craft’. Volumnia, self-righteous in her rage, gives Redgrave occasion to show that when it comes to expressing fury, women are supreme.

VOLUMNIA: I’ll tell thee what, fool! Hadst thou craft to banish him that struck more blows for Rome than thou hast spoken words?

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Physically wrestling the tribunes, Volumnia and Virgilia bring the action to fever pitch. The stay/go motif is reiterated, perhaps an admixture of futility (protesting the banishment) and venting (anger at those who pronounced it). Note the recurrence of the lover/warrior, sex/war motif (sword, posterity, bastards). The women’s verbal mastery here is a fine weapon against the men’s physical force. And yet, as mentioned, the women attack not only verbally but also physically, mother geese to the gosling Coriolanus, making the scene more poignant. All the actors, but Redgrave in particular because by age most fragile, use these verbal/physical dynamics very well.

SICINIUS: O blessed heavens!

VOLUMNIA: More noble blows than ever thou wise words, and for Rome’s good. Yet go! Nay, thou shalt stay too. I’ll tell thee what: I would my son were in Arabia, and thy tribe before him, his good sword in his hand.

SICINIUS: What then?

VIRGILIA: What then? He’d make an end of thy posterity.

VOLUMNIA: Bastards and all.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

As the tribunes leave, Volumnia, recognizing no amount of rage can undo Coriolanus’ banishment, calls on the gods to confirm her curses. Redgrave, to stunning effect, delivers the line in a three-part movement of body-voice in mezzo-forte, forte and fortissimo. Here is mezzo-forte…

MENENIUS: Come, come, peace.

BRUTUS: Well, well. We’ll leave you.

SICINIUS: Why stay we to be bated by one who wants her wits?

VOLUMNIA: I would the gods…

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Forte…

… had nothing else to do…

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Fortissimo.

… but to confirm my curses!

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

To Menenius Volumnia then confides that venting her rage is therapeutic. In delivering the line, Redgrave reverts to an intimate, confidential tone, making for a sharp contrast with what went before. This alternation of tone is, of course, keyed to Coriolanus’ alternation (and superposition) of state and family, public and private, marketplace and room-in-a-house.

VOLUMNIA: Could I meet them but once a day, it would unclog my heart of what lies heavy to it.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

To close out the scene, Redgrave adopts an imperious tone that expresses both the Roman ideal of high-minded self-sacrifice and Volumnia’s obsession with feeding, starvation and control. Her body-voice shows us she has retreated into her own world where, enmeshed with Coriolanus, she is untouchable.

MENENIUS: You have told them home. And, by my troth, you have cause. You’ll sup with me?

VOLUMNIA: Anger’s my meat: I sup upon myself and so shall starve with feeding.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

VANESSA REDGRAVE IN ‘CORIOLANUS’: ACT V SCENE 3

This scene, the longest in the film (12m15s), is the climax of Coriolanus. It is a very fine piece of cinema, with all the film arts (cinematography, acting, editing, sound, décor, costumes) coming together under Ralph Fiennes’ direction to transport the spectator into the quintessence, that transcendent domain that art promises but rarely attains. If this scene is the real thing, it is largely thanks to the performance of Vanessa Redgrave—though I hasten to add that Ralph Fiennes and Jessica Chastain are brilliant in their roles. The choreography of the scene, a series of dramatic arcs within a larger arc, is outstanding, and we need to keep the larger arc in mind as we consider the smaller ones it overarches.

Following footage of Coriolanus’ tanks beginning their assault on Rome…

Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

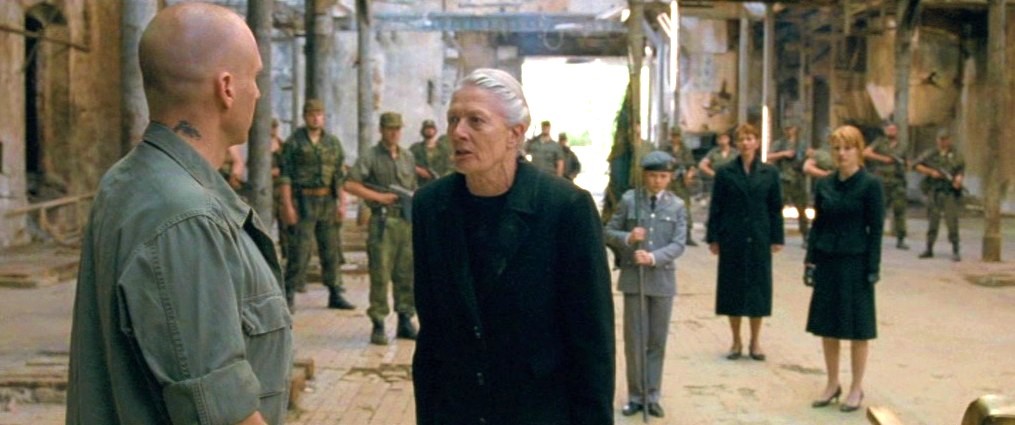

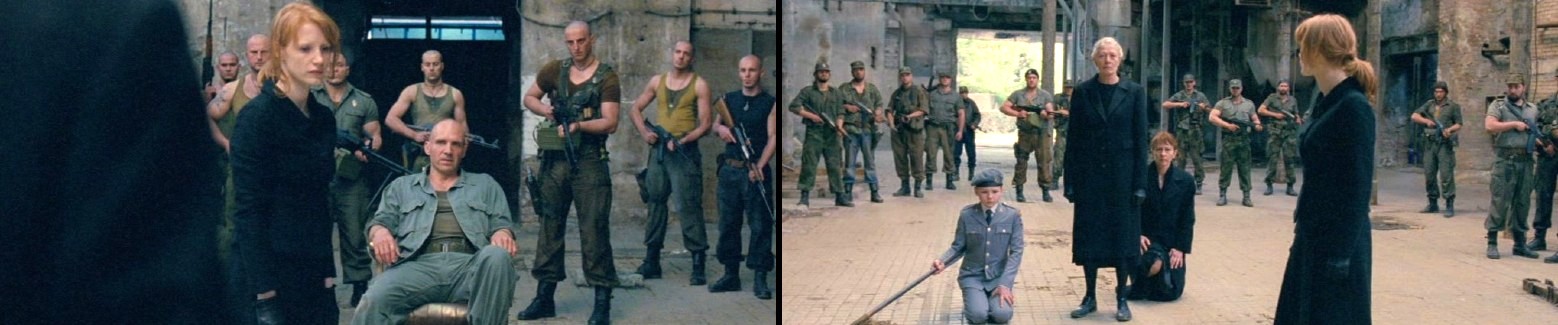

… is a series of tracking shots of Virgilia, Volumnia, Young Martius and an accompanying Lady being led by Aufidius’ lieutenant to the courtyard where, in the midst of Volscian soldiers, they will make their plea to Coriolanus to spare Rome.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Virgilia’s confrontation with Coriolanus, lasting but a minute, it is a gem of a Shakespearean moment, beautifully acted and filmed. With four simple words she salutes Coriolanus from where she stands. Jessica Chastain, in her red-haired pallor, conveys the weight of Virgilia’s silence; disdaining verbiage about fame and honour, by a look alone she cuts through the crap: ‘I am your wife, you are my husband; let our love triumph over this dirty business’, her gaze seems to say.

VIRGILIA: My lord and husband.

Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Coriolanus, fixated on revenge, is deaf to Virgilia’s silence: What she is proposing—that he open himself to love—simply doesn’t fit with the part he’s now playing. In ten syllables he tells her so.

CORIOLANUS: These eyes are not the same I wore in Rome.

Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

‘No’, she responds, ‘it’s only because grief has altered us that you think you have changed’. Virgilia, typically, is not taking things at face value: her still waters run deep.

VIRGILIA: The sorrow that delivers us thus changed makes you think so.

Ralph Fiennes, Vanessa Redgrave, Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus

‘The vase gives shape to empty space and music gives shape to silence’ (Georges Braque): Alas, in Coriolanus, Virgilia’s silence is usually met with clamour and condescension, while most often agitation leaves empty space unshaped. Here, however, Virgilia makes a ‘vase’ of gesture—touch, hands, lips—a kiss to overcome the sterility of hearing without listening, speaking without thinking. Before receiving it, Coriolanus draws on his tenderness for Virgilia, a tenderness Volumnia has not been able to stamp out, calling his wife ‘best of my flesh’.

CORIOLANUS: Best of my flesh, forgive my tyranny, but do not say for that ‘Forgive our Romans’. O, a kiss…

Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Then, however, with devastating cruelty, he poisons the kiss with bile…

CORIOLANUS: Long as my exile…

Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

… leaving Virgilia, who has no truck with martial-marital comparisons, completely unarmed. Her pain, here, is palpable.

CORIOLANUS: …sweet as my revenge!

Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Coriolanus and Volumnia then clear the ground, as it were, before proceedings proper begin. In marked contrast to Virgilia, whose spontaneous feeling cannot soften her husband’s heart, Volumnia is coldly calculating in her assault. Coriolanus’ opening gambit is to drop to his knees before ‘the most noble mother of the world’.

CORIOLANUS: You gods, I prate, and the most noble mother of the world leave unsaluted! Sink, my knee, in the earth.

Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

Volumnia, in dropping her knees now to hard stone (as she makes sure to point out), counters with a gambit aimed at shaming her son. Right from the get-go, Redgrave’s steely determination makes it clear who’s in control of the confrontation; not for a second does she leave any doubt that success is the only outcome Volumnia will accept.

VOLUMNIA: Stand up, blest, whilst with no softer cushion than the flint I kneel before thee.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Having shamed Coriolanus, Volumnia reaffirms her bond with him—‘You are my warrior’—then, seeing a little ‘window of opportunity’, she declares that she hopes to win him over. Indicating Young Martius, she continues chipping away at her son’s self-assurance by saying the boy, in time, may grow up to resemble his father, implying that to proceed with the attack on Rome would be not only to attack his family, but also to attack himself. In a word, she is trying to bind him in ‘the ties that bind’. Here, as throughout the scene, Redgrave exudes authority; no matter how humble her body-voice, she never conveys anything less than full conviction.

CORIOLANUS: What this? Your knees to me? To your corrected son?

VOLUMNIA: Thou art my warrior, I hope to frame thee. This is a poor epitome of yours, which by the interpretation of full time may show like all yourself.

Ralph Fiennes, Vanessa Redgrave, Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus

Coriolanus then addresses his son as if he were addressing himself, reinforcing his morale after the episode of shame. Just as he cruelly dismissed Virgilia’s kiss, preferring Roman ideals to human feeling, here he dismisses his son with a lesson in the nobility of killing. Volumnia too is imbued with Roman ideals, but unlike Coriolanus, she can harness them to human feelings—all the better to manipulate her son. Redgrave’s achievement, in this scene, is due in part to her ability to be as convincing on the front of feelings as on that of ideals.

CORIOLANUS: The god of soldiers inform thy thoughts with nobleness, that thou mayst prove to shame invulnerable.

Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

Volumnia, having driven home Coriolanus’ ‘unnaturalness’ in opposing his family, then switches to a less emotional mode. Redgrave, in getting ready to advance Volumnia’s ‘colder reasons’, listens to Coriolanus with a patience tinged with haughtiness (even though it is she who is kneeling), displaying the regal calm of a Volumnia used to getting her way.

VOLUMNIA: Even he, your wife, this lady, and myself are suitors to you.

CORIOLANUS: I beseech you, peace! Or if you’d ask, remember this: Do not bid me dismiss my soldiers, or capitulate again with Rome’s mechanics. Tell me not wherein I seem unnatural. Desire not to allay my rages and revenges with your colder reasons.

Ralph Fiennes, Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus

Seizing the initiative, Redgrave’s Volumnia cuts Coriolanus short with a curt ‘No more, no more!’. She stands up and, with her eyes trained on his, summarizes how things stand then makes it clear that Coriolanus alone will bear the consequences of his decision. ‘Therefore hear us’, she commands. The acting challenge for Redgrave is to temper Volumnia’s imperiousness with just the right dose of vulnerability; to humanize, as it were, the patrician in her.

VOLUMNIA: No more, no more! You have said you will not grant us anything—for we have nothing else to ask but that which you deny already. Yet we will ask, that, if you fail in our request, the blame may hang upon your hardness. Therefore hear us.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

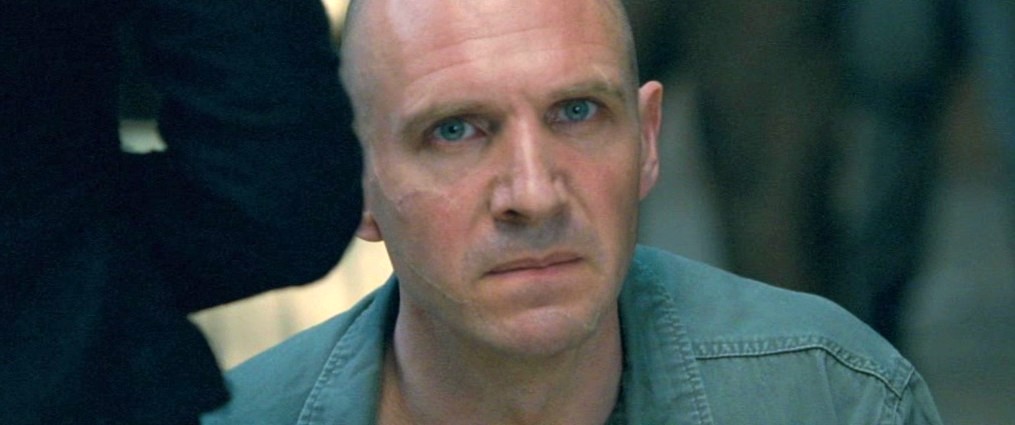

Coriolanus, his body-voice awash with swagger, now makes it clear to Aufidius and the Volsces that he has no traitorous intentions. Seated in the felicitous find of the set decorator—a barber’s chair-cum-chair-of-state—he arrogantly invites his mother to make her request. This marks the start of the mother-son duel proper. The disposition of the figures, here, is a fine example of Fiennes’ inspired ‘choreography’. Note, in particular, Vanessa Redgrave’s stance: a duelist confident in her abilities.

CORIOLANUS: Aufidius and you Volsces, mark, for we’ll hear naught from Rome in private. Your request?

Jessica Chastain, Ralph Fiennes, Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus

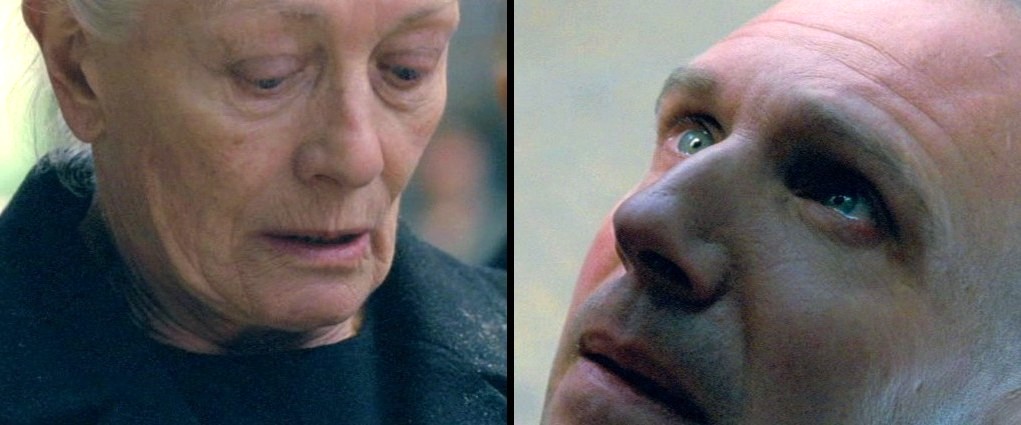

In a stroke of genius (as the director explains in his DVD commentary), Redgrave chose to play this sequence kneeling before Fiennes, her hands on his knees, adopting to great effect a tone of grave intimacy. In the vast courtyard filled with soldiers, she recreates the mother-son bubble. Taking a cue from the dialogue, she marks a moment of silence before opening her mouth, a moment that gives the measure of what is at stake. Recall the Redgrave quote I gave earlier: ‘Acting means working to be alive and alert to the incident and the moment’. This is precisely what makes this sequence so powerful; we feel the actress totally in the moment, her body-voice determining the pulse of time, a present that obliterates past and future to impose a living ‘now’. There is grief and solemnity in her regard, but she leaves no doubt, despite her gentleness here, that she is in full possession of her resources.

VOLUMNIA: Should we be silent and not speak, our raiment and state of bodies would betray what life we have led since thy exile.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Mixing gravitas and pathos, Redgrave gets into the heart of Shakespeare’s writing, using family affairs to leverage affairs of state, affairs of state to leverage family affairs. Her Volumnia is so convincing that Coriolanus forgets that the ground of tenderness and restraint she is trying to draw him onto is precisely the ground they both typically disdain. The actress, here, is called upon to cancel out this contradiction. If Redgrave does it so well, it is mainly because of her intermingling of gravitas and pathos.

VOLUMNIA: Think with thyself how more unfortunate than all living women are we come hither, since that thy sight, which should make our eyes flow with joy, hearts dance with comforts, constrains them weep and shake with fear and sorrow, making the mother, wife, and child to see the son, the husband, and the father tearing his country’s bowels out.

Vanessa Redgrave & Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

In this sequence, Redgrave marks three movements. In the first, she continues the tone (gravitas and pathos) and stance (kneeling) from before, taking care, with her body-voice, to emphasize ‘foreign recreant’ and ‘thy wife and children’s blood’. In the second, she stands up and, raising her voice and accelerating her delivery, begins to announce her intention to commit suicide if Coriolanus refuses to call off his assault. Finally, in the third movement, she grabs the emblem of Roman authority, a flag on its staff (just as she did in Act II Scene 2), and points it spear-like at Coriolanus as she completes her suicide threat. Facial expression, gesture, pace, posture—by these primary elements of the actor’s art, Redgrave traces the arc of dramatic tension—and takes our breath away.

VOLUMNIA: And we must find an evident calamity, though we had our wish which side should win. For either thou must as a foreign recreant be led with manacles through our streets, or else triumphantly tread on thy country’s ruin, and bear the palm for having bravely shed thy wife and children’s blood. For myself, son, I purpose not to wait on fortune till these wars determine. If I cannot persuade thee rather to show a noble grace to both parts than seek the end to one, thou shalt no sooner march to assault thy country than to tread on thy mother’s womb that brought thee to this world.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Inspired by Volumnia, Virgilia says that she too will kill herself if Coriolanus does not relent.

VIRGILIA: Ay, and mine, that brought you forth this boy to keep your name living to time.

Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

And then Young Martius, following the example of his mother and grandmother, defies his father. There is irony here, for one may suppose that the boy, in this act of defiance, is fulfilling his father’s wish for him: ‘The god of soldiers inform thy thoughts with nobleness, that thou mayst prove to shame invulnerable’. Aided by Virgilia and Young Martius, then, Volumnia has shown that the alignment of family affairs and affairs of state does not accord with Coriolanus’ interpretation: It is he who is the odd one out. Redgrave, in the way she has unfolded her arguments and actions, in the way she has employed her body-voice, has shown that Volumnia, as written by Shakespeare, is an eminent strategist and tactician.

YOUNG MARTIUS: You shall not tread on me. I’ll run away till I am bigger, but then I’ll fight.

Harry Fenny, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Coriolanus, disturbed by what he has heard, interrupts the proceedings by rising and walking away. Pressing her advantage, Volumnia orders him to stay, then articulates the peace proposal she wants Coriolanus to make, one that would be honourable to both sides as well as to Coriolanus himself. A diplomat practicing statecraft in a public forum, a mother in a tête-à-tête with her son: Redgrave does not choose between the two approaches, but practices each simultaneously. There’s an intimacy to her tone that belies the live-or-die stakes; she understands that Volumnia can only change Coriolanus’ heart by appealing to the mother-son bond. In the face of Coriolanus’ silence after Volumnia has argued for making peace, Redgrave performs a very effective bit of acting business (illustrated below): She holds her head level and awaits a response; she lowers her head in a gesture of puzzled questioning; finally, she raises her head and spits out in frustration: ‘Speak to me, son! Why dost not speak?’ Great acting, indeed, is often made up of little details such as these, and Redgrave is a past master of the art.

CORIOLANUS: I have sat too long.

VOLUMNIA: Nay, go not from us thus. If it were so that our request did tend to save the Romans, thereby to destroy the Volsces whom you serve, thou mightst condemn us as poisonous of your honour. No, our suit is that you reconcile them so that the Volsces may say ‘This mercy we have showed’, the Romans ‘This we have received’, and each on either side give the all-hail to thee and cry ‘Be blessed for making up this peace!’ Speak to me, son! Why dost not speak?

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Seeking reinforcement, as it were, Volumnia appeals to Virgilia and Young Martius to intervene, but she knows she alone can bring about a change of heart in Coriolanus. Note that Redgrave (under the director’s guidance) modulates dramatic intensity by moving along the axis that stretches between her ‘pleading party’ (Virgilia, Young Martius, Lady) and Coriolanus. Here, with Virgilia and Young Martius, the tension is momentarily relaxed, as Volumnia searches for new tactics before returning to the attack.

VOLUMNIA: Speak you, daughter, he cares not for your weeping. Speak thou, boy, perhaps thy childishness will move him more than can our reasons.

Vanessa Redgrave & Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Though the tension may have relaxed, Redgrave, while awaiting inspiration for a new assault on Coriolanus’ resistance, keeps Volumnia’s energy level high. The nervous energy with which she delivers the line here, in confidence to Virgilia, is scintillating; she thrusts her gloved hands to her chest and lets them fall as she spits out the final phrase. The gesture works like magic: Volumnia turns on her heels to confront Coriolanus in a new line of attack. In acting, body-voice is everything.

VOLUMNIA: There’s no man in the world more bound to his mother, yet here he lets me prate like one in the stocks.

Jessica Chastain & Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

What is Volumnia’s new line of attack? It begins with a ludicrous descent from the heights of brokering a peace between Rome and the Volsces to the depths of a mother accusing her son of never having shown any gratitude, despite the sacrifices she made and the success she procured. Redgrave delivers the line up to ‘courtesy’ while walking to face Coriolanus again; facing him, she delivers the rest, reminding the warrior that he owes his honour to his mother. Closing the distance between them, she raises the tension. Note that without the excellence of Ralph Fiennes expressing on his face Coriolanus’ conflicting emotions, Redgrave would have less to draw on to generate the intensity she does.

VOLUMNIA: Thou hast never in thy life showed thy dear mother any courtesy, when she, poor hen, has clucked thee to the wars and safely home, loaded with honour.

Ralph Fiennes, Coriolanus

An iron fist in a velvet glove, Redgrave’s accusatory finger expresses Volumnia’s righteous anger as she raises the pitch of her confrontation with her son.

VOLUMNIA: Say my request’s unjust and spurn me back. But if it be not so, thou art not honest…

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Note, here, how Redgrave makes the most of her malleable face to invoke the punishment of the gods…

… and the gods will plague thee…

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

… that lies in store for Coriolanus if he does not relent. The sequence, beautifully played, works so well because Redgrave, varying expressiveness to shape dramatic line, measuring out energy to modulate its movement, never loses sight of the arc of the scene. The pertinence with which she does this is never short of compelling.

… that thou restrain’st from me the duty which to a mother’s part belongs.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

In the face of Coriolanus’ silence, Volumnia clutches at straws. First, she repeats the kneeling ploy, ‘shaming him with our knees’. Her son does not respond. Then comes an expression of resignation, of dying ‘among our neighbours’ (another shaming ploy). Her son does not respond. Finally, she draws attention to Young Martius, declaring that Coriolanus does not have the strength to deny the boy. Her son does not respond. Redgrave’s body-voice has become polyphonic; as she kneels, rises, stands, turns she express myriad emotions: anger, desperation, resignation, fear, frustration. Note how her eyes focus laser-like on Coriolanus; captured in her gaze, he can no longer turn away.

VOLUMNIA: Down, ladies; let us shame him with our knees. Down. This is the last. An end. So, we will home to Rome and die among our neighbors.—Nay, beholdst this boy, that cannot tell what he would have, but kneels and holds up hands for fellowship, does reason our petition with more strength than thou hast to deny it.—Come, let us go.

Vanessa Redgrave & Jessica Chastain, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

In a final outburst of impotent rage and fury that still believes in its power, Redgrave’s Volumnia, her out-thrust arm pointing at Coriolanus, exclaims with bitter irony that her son’s family are all in the enemy camp—her son cannot be ‘unnatural’, he must have his family with him. The intensity of Redgrave’s body-voice as she screams the line—at her son, at the gallery, at the gods—is a fitting climax to Volumnia’s plea, as is the smouldering coda she gives it. Coriolanus, with Volumnia, Virgilia and Young Martius in flesh and blood before him, now realizes the vanity of his earlier declaration, ‘Wife, mother, child I know not’ (made to Menenius in 5.2)—it simply is no longer tenable. Volumnia has won.

VOLUMNIA: This fellow had a Volscian to his mother; his wife is in Corioles, and his child like him by chance.—Yet give us our dispatch. I am hushed until our city be afire, and then I’ll speak a little.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

Volumnia’s victory is her son’s death sentence. Does she realize it? We don’t know, for she never opens her mouth again. Coriolanus’ tragedy is that out of love he chooses his mother, and out of honour he chooses death. It is fitting that love and death are inseparable, for Volumnia, in the toxic relationship she has imposed on her son, only loves him when he achieves honour. To the extent that she believes love must be earned, Coriolanus is her tragedy too. Redgrave’s expression here suggests Volumnia may vaguely be aware of that.

CORIOLANUS: O mother, mother; what have you done? Behold, the heavens do ope, the gods look down, and this unnatural scene they laugh at. O my mother, mother, O! You have won a happy victory to Rome; but for your son, believe it, O believe it, most dangerously you have prevailed with him, if not most mortal to him. But let it come.

Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus, Ralph Fiennes

In her final shot in the film, Redgrave gives Volumnia, ‘the life of Rome’, a preoccupied expression. Has it crossed her mind that she is the death of her son? For his part, Fiennes gives Coriolanus an expression of foreboding: he has no doubt what lies in store. And thus two great actors celebrate Shakespeare, and thus Vanessa Redgrave, along with the other actors across these five scenes, transports us into the transcendent.

COMINIUS: A merrier day did never yet greet Rome, no, not the expulsion of the Tarquins. We have all great cause to give great thanks. Behold our patroness, the life of Rome!

Ralph Fiennes & Vanessa Redgrave, Coriolanus

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

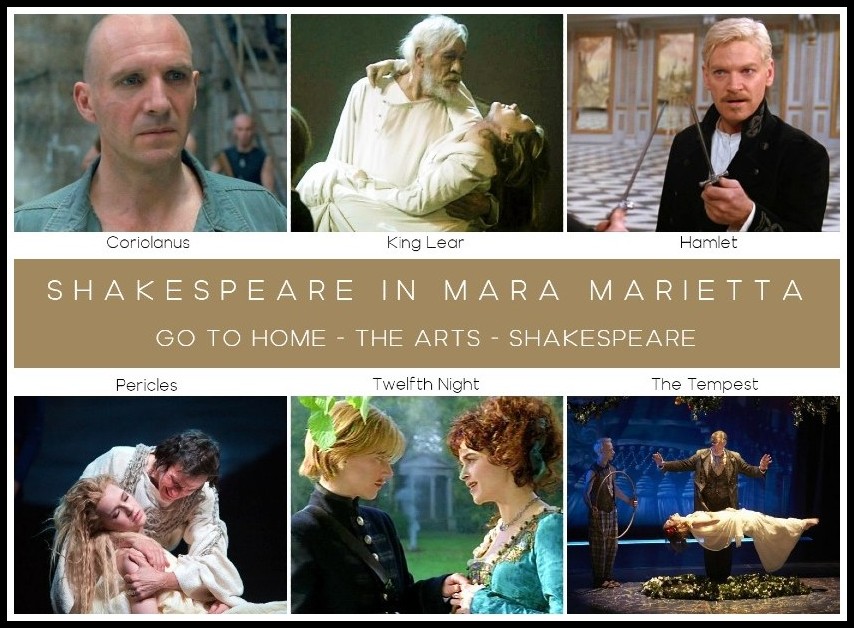

IMAGES IN RANDOM ORDER, FILM LIST BELOW IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER

Besieged, Cat People, Cul de Sac, Damnation, Don’t Come Knocking, Fellini’s Casanova, In the Realm of the Senses, Je t’aime moi non plus, Kill Bill, La Belle Captive, Last Tango in Paris, Meshes of the Afternoon, Possession, Spetters, Taxi to Portugal (aka Family Matters), Teorema, The American Soldier, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, The Element of Crime, The Man Who Fell to Earth, The Mother and the Whore, The Passenger, Un Chien andalou, Viva Maria

SHAKESPEARE IN MARA MARIETTA

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2021| All rights reserved

Comments