Every exploring, rigorous novelist is an exile of sorts

WRITERS AND EXILE

Christine Brooke-Rose

Abridged from Christine Brooke-Rose, ‘Exsul’ in Exile and Creativity, ed. Susan Rubin Suleiman (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998) pp. 9-24

Christine Brooke-Rose, late 1950s | Photo: Ida Kar

I – INTRODUCTION

There are many different kinds of literary exile. At random from memory, in roughly chronological order: ‘Isaiah’, Ovid, Virgil, Cavalcanti, Dante, Petrarch, Thibault de Champagne, Charles d’Orléans, Voltaire, Mme de Staël, Adam Mickiewicz, Shelley, Keats, Byron, Cyprian Norwid, Charles Baudelaire, Victor Hugo, Heinrich Heine, Oscar Wilde, Henry James, Joseph Conrad, Gabriele D’Annunzio, W. B. Yeats, Edith Wharton, Tristan Tzara, Kurt Schwitters, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, H.D., Djuna Barnes, Henry Miller, Radclyffe Hall, D.H. Lawrence, Max Beerbohm, Somerset Maugham, Stefan Zweig, Bertolt Brecht, André Breton, Christopher Isherwood, Aldous Huxley, W.H. Auden, Thomas Mann, Malcolm Lowry, Witold Gombrowicz, Vladimir Nabokov, Paul Bowles, Jane Bowles, Samuel Beckett, Eugene Ionesco, Jorge Semprun, Luis Cernuda, Milan Kundera, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Harry Matthews, Italo Calvino, Anthony Burgess, Muriel Spark, and no doubt many others, all the way to the modern ‘foreigners’ or ‘postcolonials’ who write in English or French today, from Kazuo Ishiguro to Salman Rushdie.

Muriel Spark, 1984 (Photo: Stephen Hyde) | Jane Bowles, 1947 (Photo: Karl Bissinger) | Djuna Barnes, 1925 (Photo: Berenice Abbott)

II. EXILE: FORMAL AND THEMATIC

In older times, before the rise of the nation-state, when literary forms and themes were more restricted as well as more universal within a common temporal culture (medieval, classical, etc.), many writers in exile simply continued to write what they would have written at home. Petrarch, Charles d’Orléans, Thibault de Champagne (courtly lyrics); Shelley, Keats, Byron, Hugo (lyrics, romantic epics, classical elegies, etc.), Voltaire (satires, tragedies, romans philosophiques, essays), Mme de Stael (novels, essays). In other words, despite the inescapable language differences, the formal and thematic idiom was closer to the universal language of music: Handel could live in England but compose in the classical idiom, whereas it is impossible to consider Schubert or Dvorak apart from their use of folk song motifs. The analogy is of course inexact, but broadly helpful.

John Keats (Joseph Severn, 1819) | Percy Bysshe Shelley (A. Clint, after Amelia Curran (1829/1819) | Lord Byron (Thomas Phillips, 1825)

With the development of romantic realism in the nineteenth century, many exiled writers wrote about the society they had left behind. Although forms remained universally recognizable, however developing, there was a shift in subject matter, so that a new distinction can be made between those whose themes look back in either traditional or more experimental forms, and those whose themes, often with more formal experimentation, transcend the condition of exile. This distinction can be illustrated with Joyce versus Beckett. Joyce, though boldly experimental in form, continued to write about the Ireland of his youth, first realistically then mythologically in a wholly transformed, interlinguistic new idiom that transcends the earlier realism; whereas Beckett, also pushing the boundaries of novel or play beyond familiar forms, writes much simpler English (and later French), yet leaves Ireland far behind.

Samuel Beckett, early 1960s (Photo: Peter Keen) | James Joyce, mid-1930s (Photo: Berenice Abbott)

In a general sense this abandonment of the local is true of many modern writers. Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain is not merely about a sanatorium, Djuna Barnes’s characters are placeless, and so on. Gertrude Stein said this about herself: I am an American and I have lived half my life in Paris, not the half that made me but the half that made what I made. Later, she elaborates: What is adventure and what romance? Adventure is making the distant approach nearer but romance is having what is where it is which is not where you are stay where it is. Those who make things ‘inside themselves,’ she goes on, do not need adventure but they do need romance: It has always been true of all who make what they make come out of what is in them and have nothing to do with what is necessarily existing outside of them it is inevitable that they have always wanted two civilizations. There is no possibility of mixing up the other civilization with yourself you are you and if you are you in your own civilization you are apt to mix yourself up too much with your civilization but when it is another civilization a complete other a romantic other another that stays there where it is you in it have freedom inside yourself which if you are to do what is inside yourself and nothing else is a very useful thing to have happen to you and so America is my country and Paris is my home town.1

1 – Gertrude Stein, What Are Masterpieces? 1940

Man Ray, Gertrude Stein Sitting in Front of Her Portrait by Picasso, 1922

Whether we agree or not with this elaboration, it is true that the American expatriate in Paris is strangely immune to French influence, in much the same way that Joyce wrote about Dublin independently of Paris or Trieste. As Shari Benstock remarks,1 the English or American women who settled in France during the twenties [and most of the men] wrote about the English and the Americans, and ‘were not affected by French mores and customs,’ since it was ‘the need for separateness that brought them to Paris,’ as well as, no doubt, economic and other advantages—the favorable rate of exchange, the sexual freedom, the liquor unavailable in Prohibition America, and ‘being geniuses together.’2 Hemingway, with his Parisian, Italian, Spanish, and African locales, is a notable exception, but then he hardly remained in one spot, and might be classed by Stein under ‘adventure.’ Perhaps the most exemplary exception, going back a generation or more, is Henry James, who shifted his subtle analyses from Boston to Europe, and more especially to the gulf between the two, skillfully inverting the cliché of Americans as vulgar and Europeans as civilized. His disciple Edith Wharton, on the other hand, though living in France, remained with American drawing-room society.

1 – Shari Benstock, Women of the Left Bank: Paris, 1900-1940 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986) 78

2 – Robert McAlmon, Being Geniuses Together, 1920-1930 (University of Michigan Press, 1968)

Edith Wharton, 1889 (Photo: E. F. Cooper) | Henry James, 1884 (Photo: Elliott & Fry)

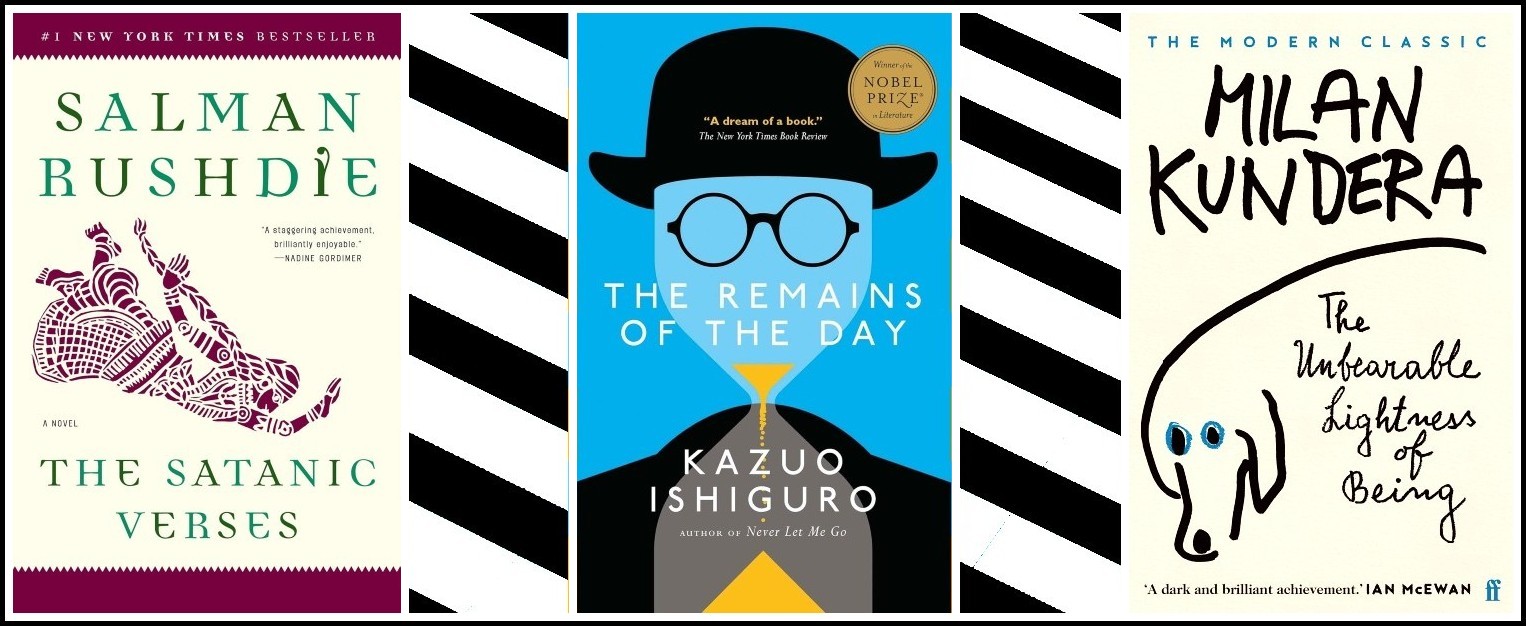

The Jamesian shift is more common today. Kundera is a good example, with The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984) already mixing Geneva into a basically Czech story, and Salman Rushdie is another. The Satanic Verses (1988) is a real clash of Indian/London cultures. Kazuo Ishiguro moved from Japanese locales and themes to a tour de force in The Remains of the Day (1989), in which the thoughts and emotions of a typically British butler pierce through his pompously distancing, alienatingly ‘correct’ idiom. Apart from the last two, all these exiles—whatever their home/abroad themes or their familiar/innovative forms, whatever lands they left or went to, in whatever condition, Babylonish exile or prison, poor or relatively moneyed—nevertheless wrote in their native tongues.

Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses | Kazuo Ishiguro, The Remains of the Day | Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

III. EXILE: LINGUISTIC

The question of language is more complex, and examples of writers who adopt a language not their own are much rarer. Joseph Conrad is the modern archetype, writing all of his work in English. Apart from two poignant short stories, Conrad never wrote of Poland, but wrote instead of the sea, of Southeast Asia, South America, Marseille, London. The other apparent exception, Under Western Eyes, with an East European revolutionary theme, has a Russian hero, and a Moscow locale, and takes place partly in Geneva. As in all of Conrad’s novels, the essential solitude of exile is transmuted away from Polish specificity. Conrad was already born in exile, in the sense that this ‘Polish’ part of Ukraine had been incorporated into Russia with the Partitions, although the idea of Poland and the Polish language remained very strong there. But Apollo Korzeniowski, Conrad’s father and a literary man, was politically active and the family was further exiled when Conrad was seven, first to Vologda north of Moscow, then back south to Chernikov, not too far from Kiev; eventually, after his mother’s death, Conrad returned to Lwów, then part of Austria, ending up as an orphan in Cracow (also part of Austria) under the guardianship of his maternal uncle. Conrad’s dream was to go to sea, and at seventeen he left for Marseille. In other words, he was born an involuntary exile in the East who became a voluntary exile in the West. But he was deeply read in Polish literature. A complex background.

Joseph Conrad, 1923 (Photo: International Newsreel) | Joseph Conrad, 1904 (Photo: George Charles Beresford)

Even today, Ionesco, Nabokov, and Beckett are rare examples of complete linguistic assimilation, possibly giving the distance needed for the transcending of regional and national themes into those of the human condition anywhere. The phenomenon of language change, however, also cuts across geographical exile, since many writers from our ex-empires write in the ex-imperial languages of French and English. The Spanish and Portuguese situation is different, since those languages stamped out the native ones, at least for literary purposes, and became the first and native languages in much older ex-empires. But the Nigerians Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, the Somali Nuruddin Farah, the Algerian Rachid Mimouni (and other African writers), Salman Rushdie (and other Indian writers), learning English or French young and perhaps even being bilingual, chose those second languages over their native idioms. How then are these various clashing features of exile (involuntary vs. voluntary, home society vs. new society, own language vs. alien language) experienced today? Such a vast subject would deserve a whole book. But since, more modestly, I have experienced both aspects of all those distinctions, as expatriate English writer and as ex-wife of Jerzy Peterkiewicz, a Polish exile writing in English, I propose to move on to a brief but more personal treatment, in the sense that I knew him well.

Vladimir Nabokov, 1968 (Photo: Philippe Halsman) | Eugène Ionesco, 1960 (Photo: Ida Kar) | Samuel Beckett, 1964 (Photo: Cartier-Bresson)

IV. JERZY PETERKIEWICZ

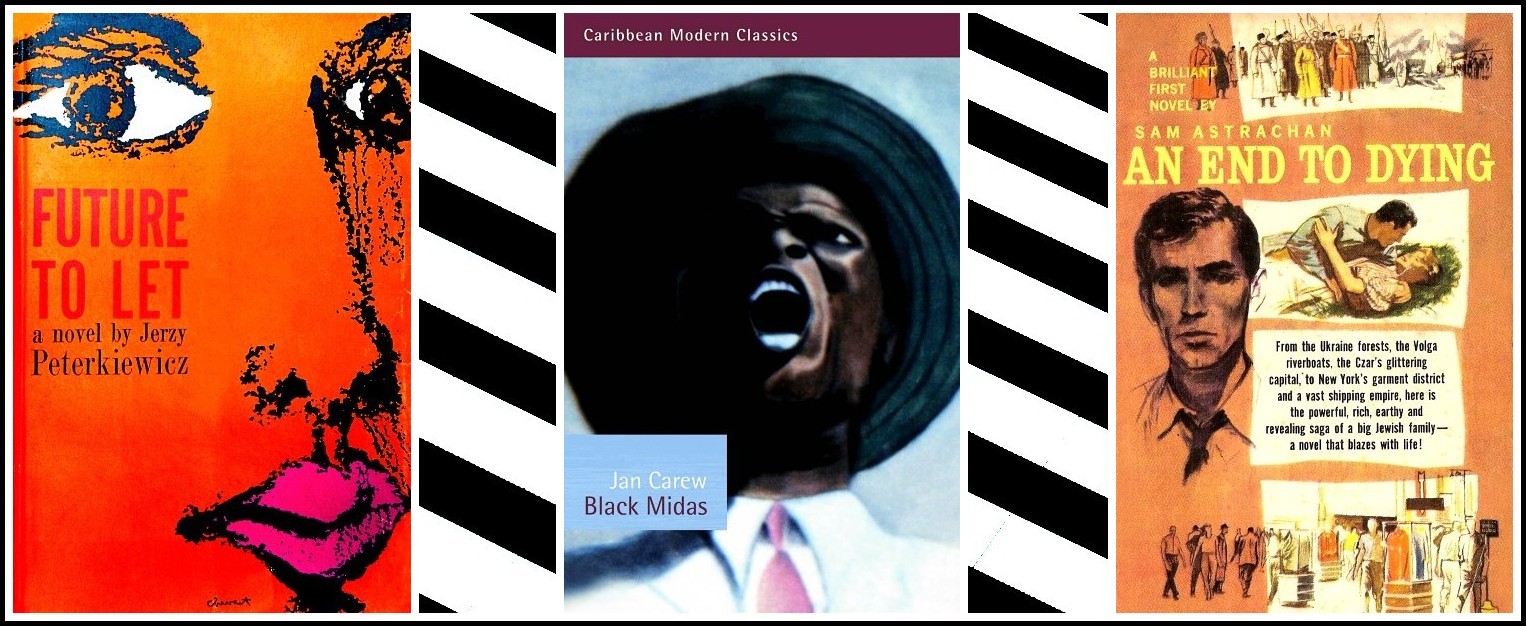

In 1958, the Times Literary Supplement published a long front-page article entitled ‘England Is Abroad,’ reviewing three English novels by foreigners: An End to Dying, by Sam Astrachan (Yiddish culture), Black Midas, by Jan Carew (Guiana), and Future to Let, by Jerzy Peterkiewicz. It was the first time, to my knowledge, that the question of foreign writers in English was raised in the TLS and the article, like all Times Literary Supplement ‘fronts,’ dealt first, and at length, with the situation of the English novel. It starts: Provincialism, like rheumatism, is the name of a disease which has as many cures as it has causes. Provincialism is a kind of cultural rheumatism, a stiffness of the joints, a pained paralysis of the executory organs, an insidious and obscure malady that will in time deform the very structure of a language, altering its every statement into the posture of parody. I would qualify the metaphor by adding that rheumatism is a very conscious pain (‘pained paralysis’) while provincialism is unconscious and self-satisfied. The author goes on to suggest that the English idiom was already in decay before the First World War. Already, by 1910, we find that many of the most accomplished writers in our language originate on the fringe of the English-speaking world and, more importantly, that they made no attempt to cover up their origins by conforming to the standards of the metropolis. On the contrary, they demand that London should accept them as they are and even suggest that it would benefit by following in their outlandish footsteps. What is more, London did. The centre of gravity of English literature shifted.

Jerzy Peterkiewicz, Future to Let | Jan Carew, Black Midas | Sam Astrachan, An End to Dying

To be sure, the author is here thinking chiefly of ‘the American influx,’ in terms of which, he complains, this remarkable revolution is too often considered, and more particularly, of Yeats, rather than of writers who (like Peterkiewicz, alone of the three reviewed) learn English late. In other words, I have momentarily slid back to the ‘formal vs. thematic,’ non-’linguistic’ part of the previous section. But not entirely. On Yeats, the author comments: Had he been born a century earlier than he was, had he been a contemporary of Tom Moore, Yeats would either have written within the English conventions, or he would have been a much more modest poet than the one we know. He could not have been both an Irish poet and a great poet because there was no cultural context in which a great Irish poet could exist, unless perhaps, he wrote in Gaelic. The power of the English language was such that he would have been transformed by it into an English poet who happened to have been born in Ireland, just as Swift and Burke are English writers though they remain Irish men. In other words, Yeats would have been like Latin writers of the Late Empire or the Middle Ages (Macrobius, Pelagius, and such), whose land of residence is seldom relevant even if known (as in Gregory of Tours, Matthew of Vendôme, etc.).

W.B. Yeats, 1935 | Photo: Howard Coster

Of the three writers considered by the TLS, Peterkiewicz was unique in having learned English late, in his twenties. Conrad was thus a frequent comparison in reviews of his English novels and, like Conrad, he was attacked by his compatriots for ‘betrayal’. But his situation, like his novels, was completely different from Conrad’s. For one thing he had a Polish literary career behind him. In that sense at least, he is more like Beckett. Born in 1916, Peterkiewicz left his Polish village in Dobrzyn at fourteen, to study and later to conquer Warsaw, where he was quickly recognized as a highly original poet, and soon was editing a literary supplement. He was twenty-three when Hitler, and then Stalin, attacked Poland in 1939. He escaped to Romania, where he fell very ill, eventually arriving in France, and escaping again in 1940 to England, still too ill to fight. The Polish government in exile helped him to attend the University of Saint Andrews in Scotland, where he recovered and learned English. In his autobiography he describes how he couldn’t understand why a lecturer talked quite so often about Ovid, only to learn later that the lecturer merely pronounced ‘of it’ in an emphatic way. That’s how little English he knew at first.

Jerzy Peterkiewicz

I met him in the British Museum library when I was twenty-three and about to go to Oxford as an ex-service and grant-supported student after the war. By then he was finishing his Ph.D. thesis and continuing to publish articles and poems in the exile press. Then, slowly, came the mutation: he not only stopped writing poetry, he turned to novels, and in English. Strange novels, both sad and funny, and deeply original. By then of course his English was fluent. And there occurred, equally slowly, a Jamesian shift in subject matter, from wholly Polish to partly Polish, to totally free and experimental. His first novel, The Knotted Cord (1953), was partly autobiographical, about a boy in a Polish village who, after an illness, is dedicated to Saint Anthony by his mother and dressed for three years in a Franciscan habit. In the second novel, Loot and Loyalty (1955), the scene shifts to Scottish mercenaries in seventeenth-century Poland (then powerful), including one Tobias Hume, a historical figure who composed songs and who, in the novel, gets involved with a newly imagined version of the False Dmitri, in other words, the exile situation reversed. The scene shifts again in Future to Let (1958), to an Englishman caught up, via the exotic Celina, with Polish exiles in London.

Jerzy Peterkiewicz | Photo: Camilla Panufnik

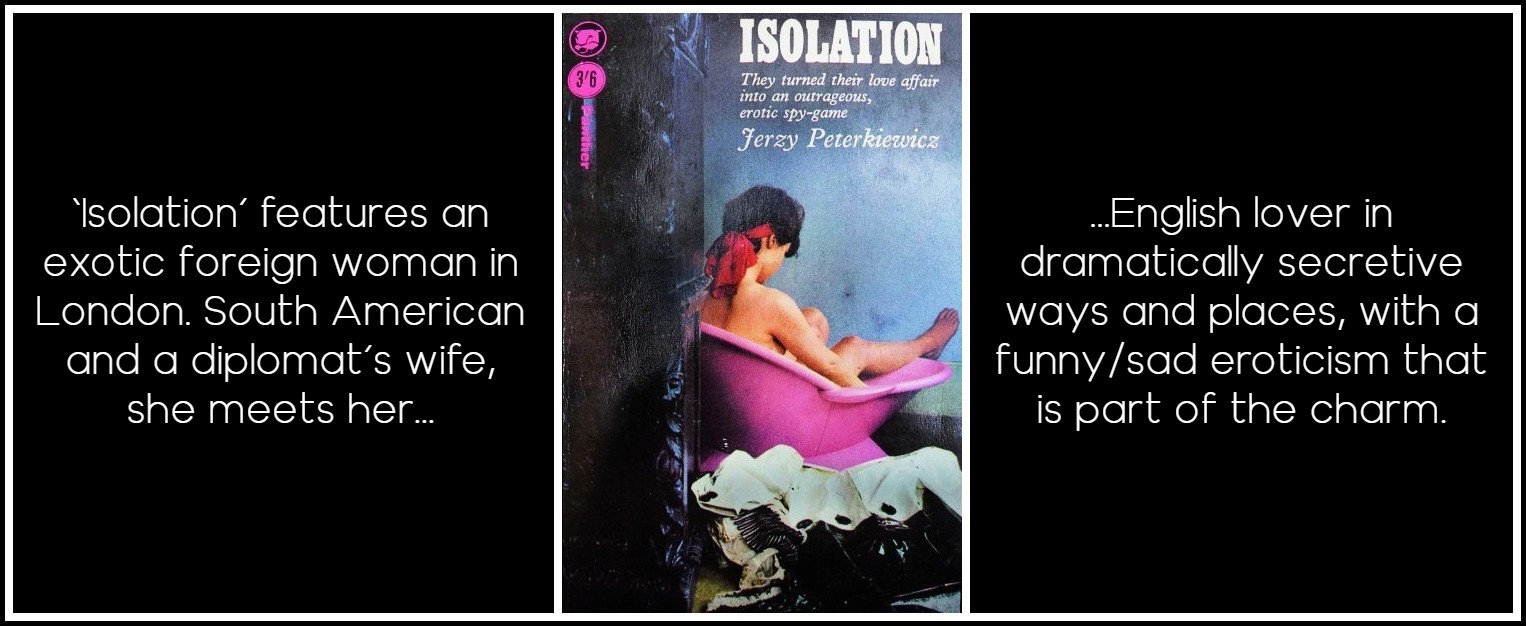

And then the Polish scene is more or less over, if the essential solitude of exile is not, and the subsequent novels are among the most unusual of the time, or even, I would add, of the period since. Isolation (1959) also features an exotic foreign woman in London, but she is South American and a diplomat’s wife, and meets her English lover in dramatically secretive ways and places, with a funny/sad eroticism that is part of the charm. The Quick and the Dead (1961) is literally about the dead and the dead living, in a weird, unplaceable limbo-locale, not in the least like a ghost story but both violent and gently poetic. We are completely out of the Polish/foreign versus London isolation. That Angel Burning at My Left Side (1963) returns East, to the border-land between Poland and (now ex) East Prussia, with a hero searching for an unknown father, but it soon shifts to other regions, in sections named after the points of the compass, ending in Italy. Then comes Inner Circle (1966), written in a spiral structure of recurring layers called ‘Surface,’ ‘Underground,’ and ‘Sky,’ apparently, but only apparently, unlinked. ‘Surface’ describes a future people who emerge out of boxes to a much reduced living space on the surface, having barely a square meter each to stand on; ‘Underground’ is the perpetual journey of a schizophrenic boy, Patrick, on the London tube train; and ‘Sky’ is the story of Eve, already separated from Adam, living in a world of animals which is invaded by monkeys, with whom her daughter goes off to live. The link is in the title, the inner circle of solitude, echoed in the spiral structure. The treatment is like skating on thin ice, a light and graceful dance above cold, unseen depths. The last novel, Green Flows the Bile (1969), about a dying British fellow traveler on a last visit to Eastern Europe, returns to a more realistic, satirical, even oddly prophetic vein, and was the first to be less well received.

Jerzy Peterkiewicz, Isolation, 1959

Why then was this highly original writer forgotten? Partly, I think, because he came too soon to be truly comprehended; partly because England woke up out of provincialism so that many other innovative novels began to attract all the attention; but mostly, I would venture, because Peterkiewicz stopped writing novels, though he continued writing essays, radio plays, an autobiography. Sheer persistence can also be part of survival. Conrad, after all, did not really pierce through until Chance, his twelfth novel. And why did he stop? He stopped when I left, but I have to insist here that there is no connection: literary gossips might say that he couldn’t have written his novels without my support in English, or even, who knows, that I wrote them, but the second hypothesis is impossible and the first ridiculous. I contributed only encouragement and enthusiasm, and he had plenty of that elsewhere. Perhaps he got discouraged by the bad reception of the last novel. Perhaps the sheer distance from his origins was too great. Conrad after all could and did revisit Poland; Peterkiewicz was blacklisted by the Communist regime and did not return to Poland until 1963, well after he became a British subject. Now that Poland is free, he is welcome there again, his poetry is republished, his English works translated. Perhaps he is resourcing himself, or, more simply, returning to source.

Jerzy Peterkiewicz

V. CHRISTINE BROOKE-ROSE

This brings me back to the question of exile. I too am astride two languages and cultures, but since this fact is usually dealt with by the few who write about me as an expatriate in France, I shall say nothing of myself, except the following: exile is an immense force for liberation, for extra distance, for automatically developing contrasting structures in one’s head, not just syntactic and lexical but social and psychological; it is, in other words, undoubtedly a leaping forth. But there is a price to pay. The distance can become too great, the loss of identity as writer in the alien society at least for one who shies away from other expatriates or ‘being geniuses together’ (if any there be) can be burdensome; the new live language can feel more and more remote. So one has to fight all that as an extra effort, although that effort can also result in escaping the familiar phrase, the expected word, simply because it no longer comes into one’s head, so even here there is advantage. But it is easy to drift into not making the effort at all.

Christine Brooke-Rose, 1964 | Photo: Mark Gerson

VI. AN EXILE IN ONE’S OWN COUNTRY

Finally, I should like to widen the whole concept of exile beyond the notion of territorial or linguistic boundaries. For it is also possible to feel an exile in one’s own country. In Born in Exile (1892) George Gissing follows the career of Godwin Peake, who as a poor boy gives up an opening to brilliant studies because his Cockney uncle decides to open an eating house, under the name of Peake, opposite the entrance to Midland College, which is giving Peake his chance. But he never gets over it, and longs to enter the society from which he has so snobbishly excluded himself (the parallel in Gissing’s own life, marriage to a prostitute, was much more ‘shameful’). Since the only way a lower-class young man could do this was to marry an upper-class girl, and since the only way to do that was to become a parson, Godwin Peake, rationalist and nonbeliever, goes through an elaborate pretense of studying to enter the church, partly to retain financial help of his Midland benefactress, but mostly to gain entry into the magic circle of the girl’s rich family and friends. Eventually he is not only found out but thoroughly ashamed, and, with his whole scheme and his genuine love collapsed, he leaves the country, catches a convenient fever, and dies in Vienna. But this seems purely fortuitous, for the sake of the last sentence, uttered by his friend Earaker: ‘Dead, too, in exile!’ was his thought, ‘Poor old fellow!’.

George Gissing, 1880

Peake is like Jude Fawley in Jude the Obscure, the archetype of the clever Victorian young man without means, stifled by conventions he hates yet acknowledges, akin to Wells’s little man with social handicaps, and to many similar characters in Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Gogol, or Lawrence, all the way to the English picaresque of the fifties, usually about misfits who make it. Gissing made social exile his permanent theme, with infinite variations: all the characters living well below the poverty line in The Nether World (1889) are social exiles, notably Clara Hewett, who tries to get out, with tragic consequences, and inversely Sidney Kirkwood, happy in a cut-above job, helpful to all, who sacrifices a possibly rich marriage to a girl he loves to marry Clara, now disfigured and discontented, out of pure generosity. Others are Bernard Kincote in Isabel Clarendon (1886), and Jasper Milvain in New Grub Street (1891). Then, as Gissing moved upmarket (at least thematically), the social exile is often richly transmuted: Miriam Baske, a strictly puritan young widow among rich and cultivated English friends in Naples, fiercely resisting the lure of culture (The Emancipated, 1890); Harvey Rolfe, a gentleman on the edge of frivolous society by choice, and his wife Alma, daughter of a dishonest and suddenly ruined millionaire, who thinks she can nevertheless make it in society as a professional singer (The Whirlpool, 1897).

George Gissing, The Nether World and New Grub Street

Rooted in all types of literary exile is the desire to integrate vs. not to integrate: the desire to remain integral to the society left behind rather than to merge with the society lived in (Adam Mickiewicz, Joyce); the desire not to belong to the society left behind but to a more desirable society (Gissing, Conrad, James); the desire not to integrate either with the society left behind, except thematically (the need for separateness) or with the society lived in (the American expatriates); and many more ambiguous postmodern variations (Kundera, Calvino, Beckett, Ionesco, Nabokov, and, more tangentially perhaps, Peterkiewicz).

Nabokov, 1968 (Photo: Philippe Halsman) | Joyce, 1935 (Photo: Boris Lipnitzki) | Kundera, 1967 (Photo: Jovan Dezort)

VII. EVERY EXPLORING, RIGOROUS NOVELIST IS AN EXILE OF SORTS

Ultimately, is not every poet or ‘poetic’ (exploring, rigorous) novelist an exile of sorts, looking in from outside onto a bright, desirable image in the mind’s eye, of the little world created, for the space of the writing effort and the shorter space of the reading? This kind of writing, often at odds with publisher and public, is the last solitary, non-socialized creative art. Music needs performers, painting often needed teams in the past, and now often needs experts in modern inventions such as electronics or plastics, as sculpture and architecture always have. The dramatist needs production, the best-selling author needs media hype, the scriptwriter is a contributor to a film. Reading, too, which used to be shared aloud, is the last solitary activity, compared with struggling against the crowd at an exhibition, going to the theater or the cinema. The circle of light on the page, excluding the world, the escapes from it in stray thoughts and imaginative leaps, for writer or reader: an imagined world, an ‘inner circle,’ within the island of exile.

Christine Brooke-Rose | Photo: Alexa Brunet

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments