Emily Brontë

WUTHERING HEIGHTS: DOUBLE-TALK & DOUBLE VISION – PART 1

Stevie Davies

Posted by kind permission of Stevie Davies, novelist, essayist and short story writer; fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and the Welsh Academy; Professor of Creative Writing at Swansea University.

From Stevie Davies, Emily Brontë: Heretic (London: The Women’s Press, 1994) 60-73

John Everett Millais, The Twins Kate and Grace Hoare, 1876

Wuthering Heights speaks to us all, women and men alike, of the deepest dreams, fears and desires of which we are capable. It arrests us from the first moment in our lives at which we take up the book and begin to read of Catherine and Heathcliff, and then of another Catherine and Hareton, involving us in a world which seems at once so foreign and so familiar. It is as if we had always been living somewhere near or somehow within the book. Such foreignness and familiarity share the same root, for this text has the quality of mystery and inscrutability of everyday life, but with the ‘givens’ removed. Life comes before us in all its unaccountable and provisional uncertainty, a mesh of anecdote, surmise, query, hypothesis and observation, arousing the unanswerable questions smothered on a day-to-day basis by the thick-piled carpets and cushions of routine: ‘Where do we come from? Where do we belong? Are we inside or outside? How does the present moment link with past and future, life to date and death to come?’ Most keenly of all, perhaps, ‘Whom do we love and how may she or he be found and kept?’ Wuthering Heights, a woman’s book, has invented a language to speak of eternal things without distinction of male and female, recreating gender in the light of a common mother and mother-tongue. Mastering the privileged ‘male’ discourse of the English language, Emily Brontë assimilates it to the ancient and repressed mother-language of oral narrative and ballad. Twin narrators, a man and a woman, doubly deliver the story and frame it in their judgements: the man, Lockwood, commits to paper a version of what the woman, Nelly, recounts orally; and Nelly’s story contains a gathering of other oral accounts, ordering and relating fragmentary glimpses of an elusive truth.

Mary Cassatt, The Reader, 1877 | Joseph Wright, Man Reading, 1770

This double delivery echoes the powerful duality of the bonded but sundered hero and heroine, Cathy and Heathcliff, whose speeches ring in our memories days or years after the book has been reshelved. Female and male voices throb with the same passion of need—primary, infantile, sublime—calling out of the window of the novel into the reader’s life, to something which answers inarticulately in ourselves, behind the window of our own needy eyes: ‘Oh, he’s dead, Heathcliff! he’s dead!’; ‘Cathy, do come. Oh do–’; ‘Heathcliff, I shall die’. Yet around these voices, an ironic and distancing narrative voice sits in censorious judgement, mocking their vagaries and rebuking their nonsenses and impieties (‘Give over with that baby-work!’) while it also sympathizes with their griefs and designs stratagems of containment and control. Skeptical narrative commentary opposes the speeches and acts it endeavours to superintend; as if with the severity of the conscious mind repressing the heat of unconscious desire; or like a civilized adult holding down a child. Wickedly, the net result of this adept textual manoeuvre is to persuade us to burn all the more ardently with the protagonists, since the ‘consciousness’ of the narrative has stepped in and so exerted its reason for us that we are spared the trouble of exerting ours.

Frederic Leighton, Flaming June, 1895

For instance, it provides a double rationalistic explanation of Lockwood’s hair-raising second dream of the revenant as the work of a fir-bough tapping on the window and acting upon the inflamed brain of a youth who has gone to bed in a strange house with a headful of swirling thoughts provoked by graffiti on the window-sill and snoopings into a naughty girl’s inflammatory diary. This time, the author even incorporates the material cause into the sleeper’s mind as part of the dream-mechanism, accounting for the unaccountable: ‘I heard, also, the fir branch repeat its teasing sound, and ascribed it to the right cause’, but leading directly into a deeper horror of the unaccountable as the dreamer sticks his hand out through the glass to break off the branch to close on ‘the fingers of a little, ice-cold hand’. The ‘ghost’, therefore, can be explained away. But it is not. There can scarcely be a reader who emerges without the sense that Lockwood has happened upon the heart of a mystery; barging into the depths of the mind of the house; a house which picks up dreams at the depths of his own mind and shows him what he didn’t know he was: Terror made me cruel; and, finding it useless to attempt shaking the creature off, I pulled its wrist on to the broken pane, and rubbed it to and fro till the blood ran down and soaked the bed-clothes: still it wailed, ‘Let me in!’ and maintained its tenacious gripe, almost maddening me with fear.

John Frederic Greenwood, Wuthering Heights, 1924

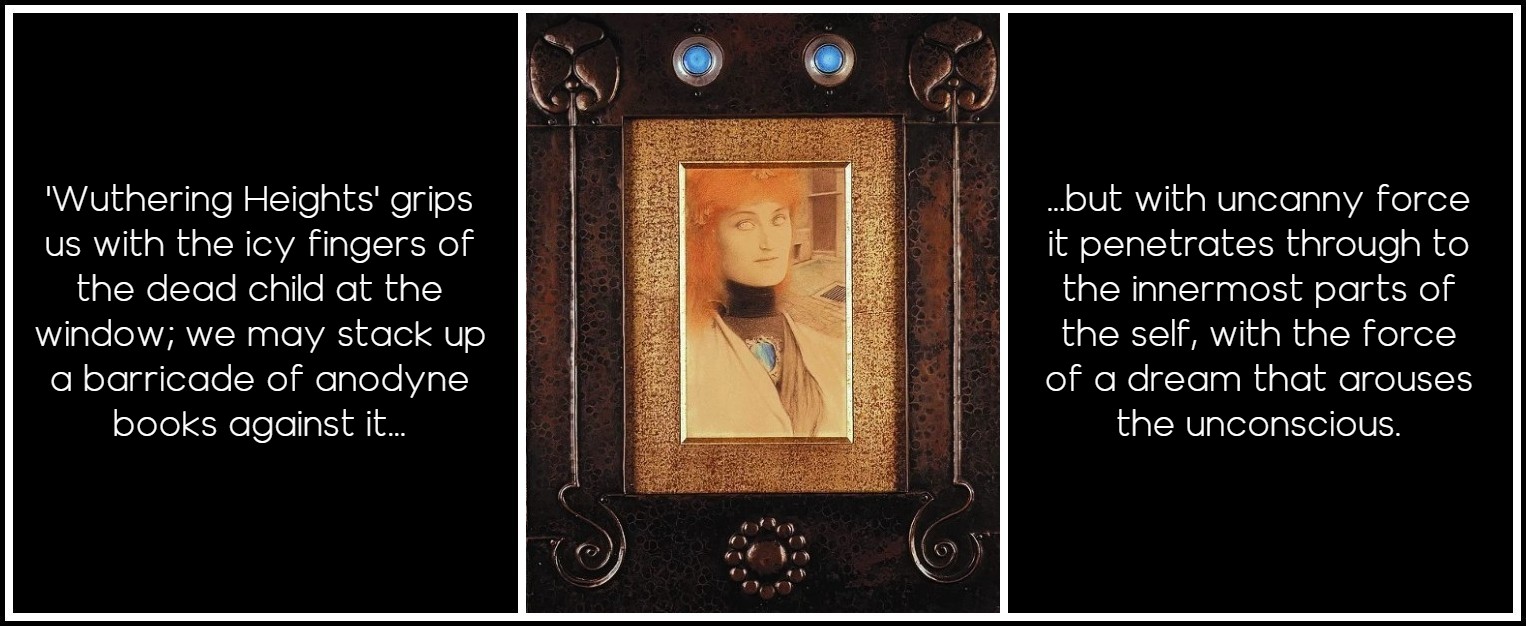

What Heathcliff would give his life to dream is ironically begotten upon Lockwood as a nightmare. In Cathy’s bed-space the narrator struggles to repel its spectral intrusion into the privacy of his mind. And in turn he begets the dream upon the reader. Our minds struggle with its horror and meaning, conscious that Emily Brontë is striking a chord in the irrational mind which finds an echo in us all. This civil, effete soul who stands in for us as reader of the characters of the Heights and the characters of Cathy’s journal, is moved to the bloodiest depths of his being by these testaments and (in sleep) performs the most appalling act of the novel. Wuthering Heights grips us with the icy fingers of the dead child at the window; we may stack up a barricade of anodyne books against it but with uncanny force it penetrates through to the innermost parts of the self, with the force of a dream that arouses the unconscious. And as it reaches in to the centre of the reader, it mocks the paper-thin frailty of her or his defences.

Fernand Khnopff, Who Shall Deliver Me?, 1896

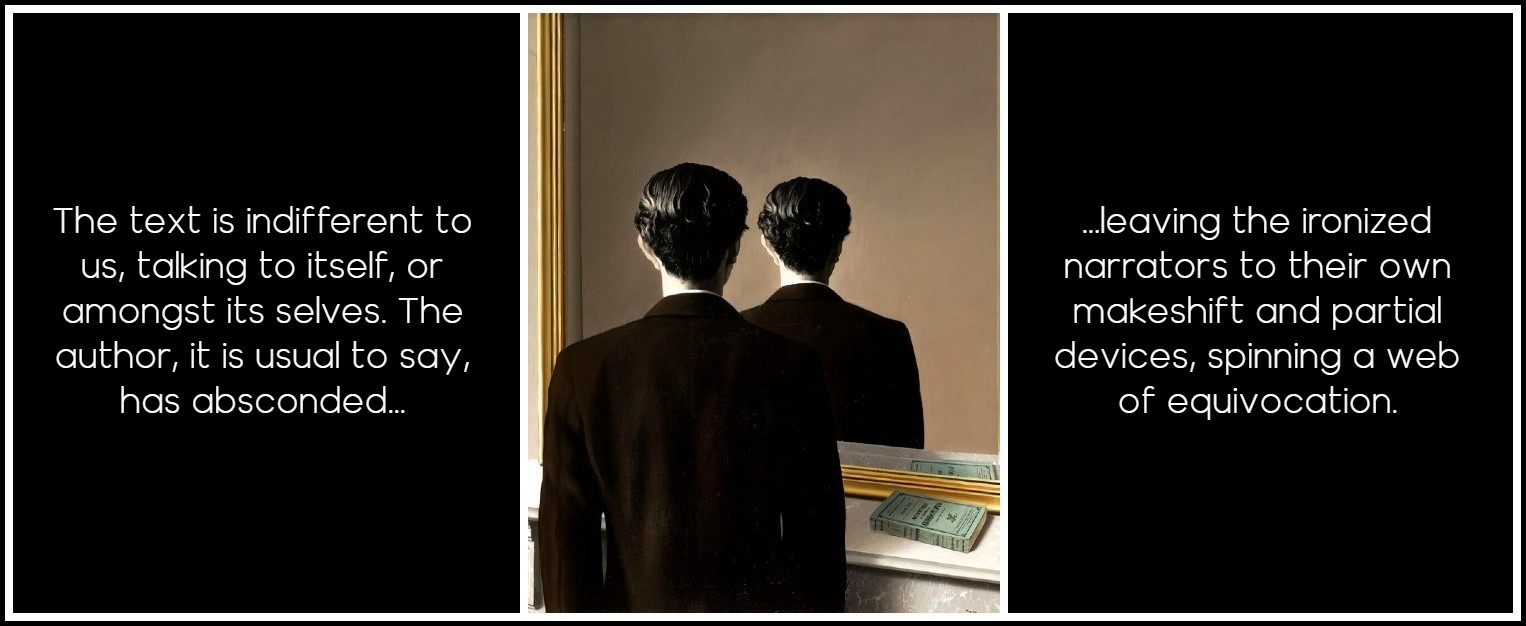

At the same time the novel bars us out from a full and satisfactory penetration of its meanings. That indeed is a condition of its endless success—a success which is absolute in the measure that the novel is inconclusive. Permitting us to think what we like about the events revealed and concealed, it frankly admits that it does not care how we interpret them. ‘You’ll judge as well as I can, all these things,’ shrugs the inner narrator to the outer, ‘at least, you’ll think you will, and that’s the same’. The text is indifferent to us, talking to itself, or amongst its selves. The author, it is usual to say, has absconded, leaving the ironized narrators to their own makeshift and partial devices, spinning a web of equivocation. No authoritative voice tells us what to think. Perhaps it would be more precise to say that the author is everywhere. For it is an illusion that first person narrative is more ‘personal’ and confessional than third person, and a vanishing author leaves traces throughout her testament, labyrinths of stratagem. Wuthering Heights, with all its complexity and relativism, presents itself as a representation or reproduction of a whole mind—but neither single-minded nor static. The mind of Wuthering Heights, like the house of that name, is a dynamic and self-divided forcefield of mental energy, all conflict and counter-currents.

Magritte, Reproduction interdite, 1937

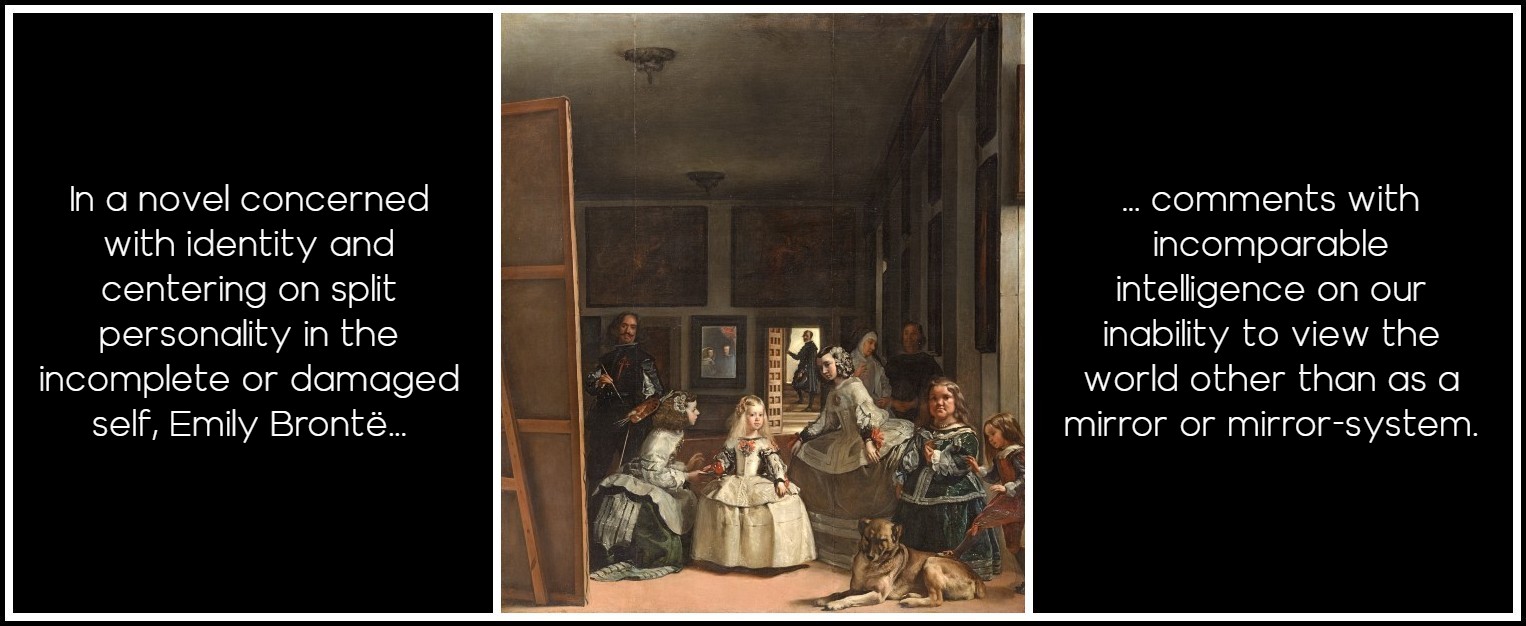

Each individual, Schlegel had believed and medical science went on to ‘prove’, is binary, the cerebellum twin-lobed, its will and desires double, and, as this is true of personality in Wuthering Heights, so it is true of the novel’s psyche. The novel shapes, composes and rationalizes mental contents which are compulsive and driven. The systematic evolution of its conflicts in a two-generation saga works into cyclic form the kinesis and catharsis of the original energies and passions. But if Wuthering Heights is the mirror of a mind, it is one which we seem to overhear thinking about its own thinking. For, not content with representing, say, Catherine’s thoughts or Heathcliff’s actions on the page, it also represents the difficulty of interpreting them and the instability of all interpretations based on the fragmentary nature of human testimony, together with the dubiety of language and our limited reasoning resources. In a novel concerned with identity and centering on split personality in the incomplete or damaged self, Emily Brontë comments with incomparable—almost dismaying—intelligence on our inability to view the world other than as a mirror or mirror-system.

Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656

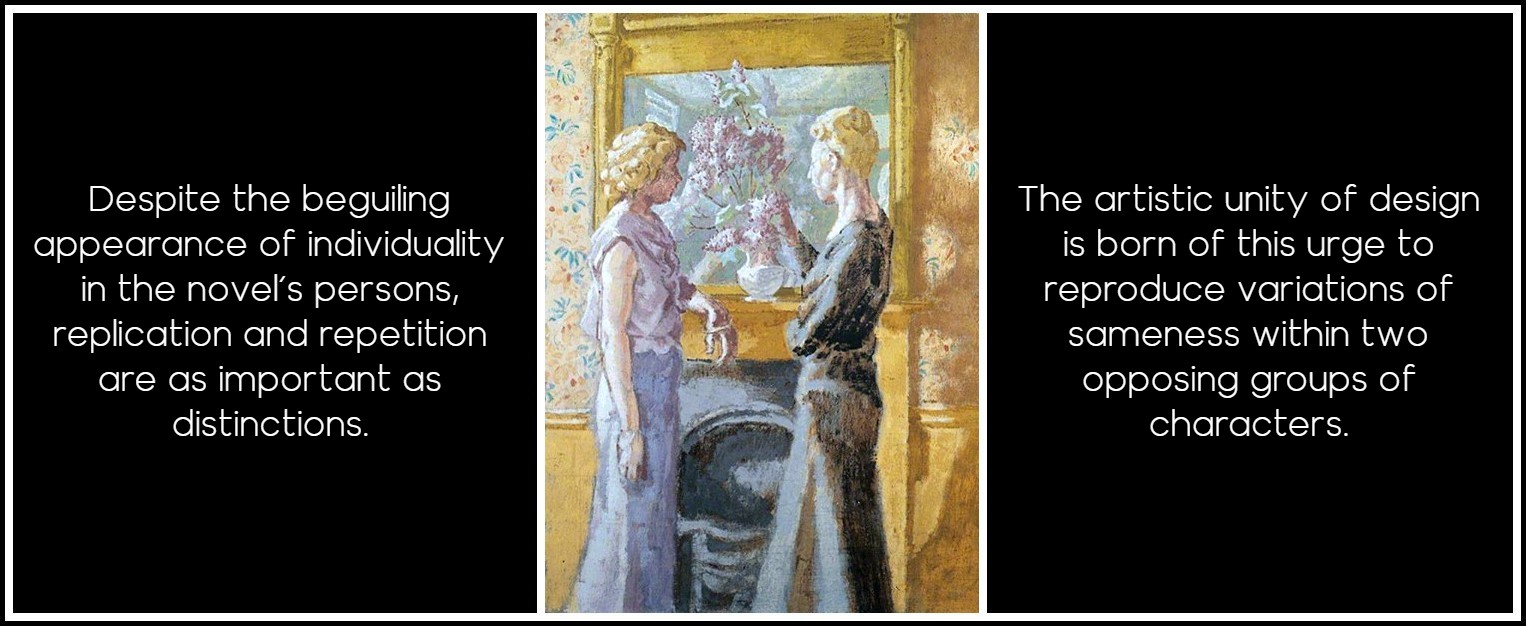

And yet at the same time she cunningly tempts us to do just that. Cathy’s ‘I am Heathcliff’, her ‘he’s more myself than I am’ are only the passionately beautiful centre of a written seduction of the reader into depths of primal narcissism which call us all—women and men—home to origins: our first home and kin, the earliest self which had not quite parted company with source. It sets us longing for someone to make up for these losses, through its artful positioning of multiple mirrors radiating in every direction so that ‘I’ become reflected in all or nearly all the persons, places and bondings of the text. In so doing, Wuthering Heights abolishes characterization in the traditional sense. Despite the beguiling appearance of individuality in the novel’s persons, replication and repetition are as important as distinctions. The artistic unity of design which justly amazes the reader is born of this urge to reproduce variations of sameness within two opposing groups of characters. The provision of too few names for the people is reinforced by the way names tend to confine themselves to a succinct area of the alphabet and by the manner in which situations and actions repeat one another. Hindley degrades Heathcliff who degrades Hareton; Catherine Earnshaw becomes Catherine Linton who bears a daughter Catherine Linton who marries to become Catherine Earnshaw. Parsimony with events, which do not so much unfold or exfoliate as recycle and regroup, not only stimulates a sense of mystery and universality but powers the energy of the narrative like a mass of water through a narrow channel. Emily Brontë’s English, uniquely terse and laconic—mean with adjectives, strong on solid nouns, free with forceful verbs—intensifies this sense of narrative momentum driving through tight constraints.

Thérèse Lessore, The Islington Twins, c. 1935

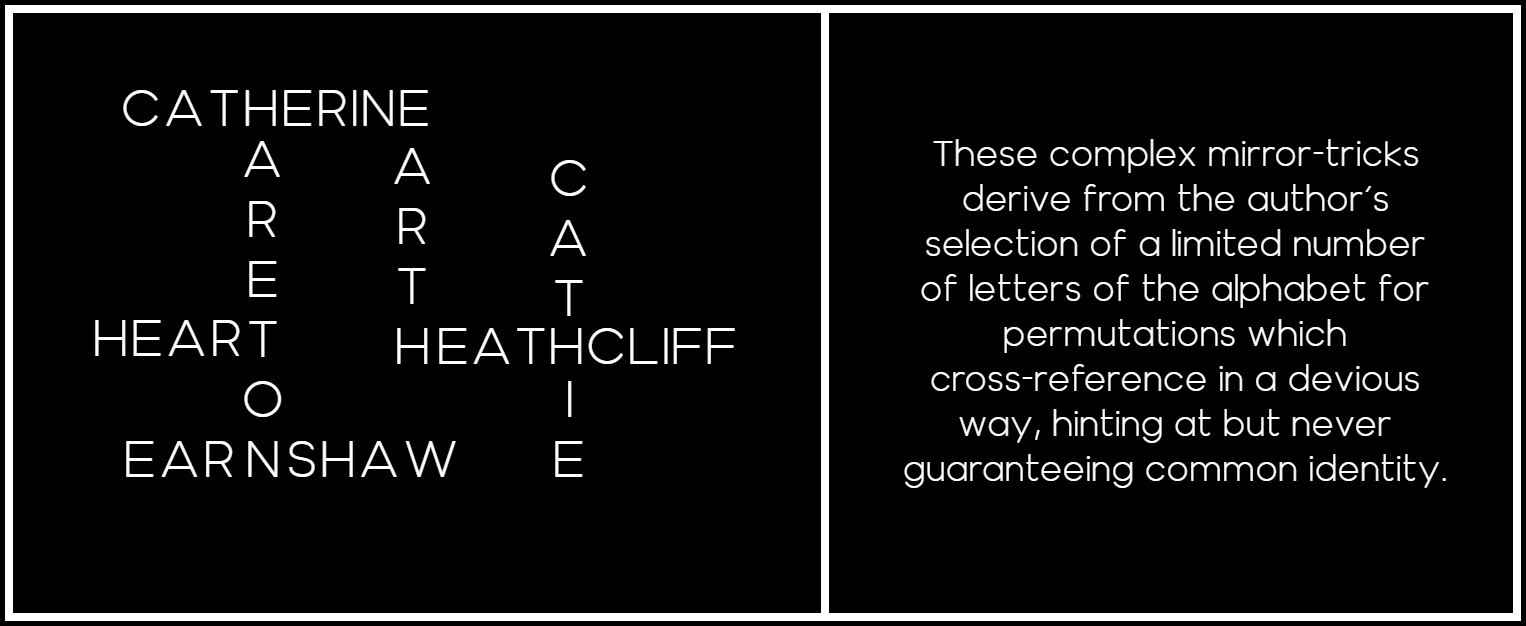

The Heights’ characters share a cryptic ground of identity both with one another and with the earth from which they came and to which they are designed to return. The central names are clearly (but not obviously) anagrammatic. Both CATHERINE and HARETON contain HEART and Emily Brontë’s favourite word EARTH, the last word in the novel. CATHERINE contains HEATH, and EARNSHAW most of the words EARTH and HEART while HEATHCLIFF, deriving in part from Earnscliffe, in Scott’s moorland tale, The Black Dwarf, compounds HEATH and CLIFF. His name contains CATHIE, whilst CATHERINE and EARNSHAW each contain most of HARETON. These complex mirror-tricks derive from the author’s selection of a limited number of letters of the alphabet for permutations which cross-reference in a devious way, hinting at but never guaranteeing common identity. Games of deep concealment and displacement are played by the mind of the novel, miming the losses and suppressions which are both its subject-matter and narrative manner. We should not be skeptical at the display of such riddling virtuosity: the least imaginative of us can produce far more ingenious word-play whilst asleep and dreaming.

Wuthering Heights, Anagrams of names

And Wuthering Heights, commanding the insight, impact, shaping power and technical expertise of dream, affects us in the same way, so that, putting the book down, we are subject to a pregnant ‘I see’ of luminous vision which fades in the telling. By dream I do not mean, of course, the woolly productions of the vegetating mind but the precise, electric intelligence brought to light by the soundings of dream from our deepest life. The novel, like much Romantic literature, is proto-Freudian in its grasp of the meaningfulness of dream:

‘Nelly, do you never dream queer dreams?’ she said, suddenly, after some minutes’ reflection.

‘Yes, now and then,’ I answered.

‘And so do I. I’ve dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and changed my ideas; they’ve gone through and through me, like wine through water, and altered the colour of my mind. And this is one—I’m going to tell it—but take care not to smile at any part of it.’

‘Oh! don’t, Miss Catherine!’ I cried.

Léon Spilliaert, Autoportrait au miroir, 1908

We notice how cagey Nelly, the voice of common sense, is about admitting that she is also a dreamer; and then how she panics and tries—three times—to repress the dream-message. Cathy, on the other hand, open to the submerged contents of her unconscious mind, is given to dream-interpretation and, in her thrilling description of the way deep dreams can charge and change identity, comes very close to articulating the powerful effect Wuthering Heights has had on generations of readers, washing through them indelibly ‘like wine through water’. This image is very beautiful and moving. Yet the effect has a shadow side, cunningly calculated to destabilize the reader by stranding her or him between illusion and reality, in that realm of eery beguilement of the Gothic nightmare, located by Emerson in a sequence of pertinent images: Where do we find ourselves? In a series, of which we do not know the extremes, and believe that it has none. We wake and find ourselves on a stair: there are stairs below us, many a one, which go upward and out of sight. Sleep lingers all our lifetime about our eyes, as night hovers all day in the boughs of the fir-tree. All things swim and glitter. Our life is not so much threatened as our perception. Dream delivers us to dream, and there is no end to illusion. The riddles of Wuthering Heights are never solved. Desire is not assuaged. If the Earnshaws echo in their names the keyword ‘earth’, it is not on but in the earth that the first generation finds its needs not resolved but dissolved and buried, for good. The novel’s inconclusive conclusion involves the concealment and underground, subversive privacy of the three graves in ‘that quiet earth’.

Léon Spilliaert, Clair de lune, 1902

Realism earths the novel’s giant compass, which never inflates into the windy excesses of Romantic cliché and gesture. Astringent irony reinforces this meticulous down-to-earthness. Lockwood has a finicking eye for detail and Nelly lives amongst pots and pans, bedding, meal-times and childhood ailments. Wuthering Heights is no Gothic castle with ramparts and crenellations but a working farm where folk are going about their business: a wash-house, coal-shed, pump, pigeon-cote are noted. So we know that the inhabitants require the means of laundering their dirty clothes, storing fuel, drawing water. All that is lacking is a latrine. The utilitarian consciousness of the author insists on the means and functions of life in the round of farm-routine: cows are milked, sheep penned and driven, rabbits hunted for the pot. The frying pan with which the dogs are clouted is a working utensil, and the fire which roars in the grate (‘an immense fire, compounded of coal, peat, and wood’), symbolic as it may be of the blazing life-force, is created of specific local fuels, imported, dug from the moor or cut from local timber. Regional authenticity is everywhere insisted upon.

Frank Bramley, A Hopeless Dawn, 1888

Food is on view: oatcakes, beef, mutton and ham. The class-system of working master, retainer, female servants and farm-hand operates. Every detail of the house-interior seems to be known; precisely observed. Indeed the house of the book is so well-built and furnished, with an eye to the stability of its architecture and decent functioning, that paradoxically its semblance of three-dimensional reality makes for a species of uncanniness. We could (we feel) go there and find it exactly so. The author behind the narrators has researched it exhaustively, and round the clock. What, for instance, is the state of the fire at 3am precisely? The ashes are hot enough to kindle a candle; cool enough for a cat to bask there. The uncanniness of the interior arises in part from its foreignness to the Southerner, Lockwood, who, blundering in to the tail-end of an untold story, lacks the gumption to ask the sensible questions and stokes the fire of mystery, the tempers of the guard-dogs and the shades of the past. The strangeness of the house and the text that represents it are established through the building of rock-solid norms of materiality and functionality, with vacant spaces and recesses, withheld from our consciousness.

Farm building at Fell Beck near Pateley Bridge, Yorkshire (datestone: 1685)

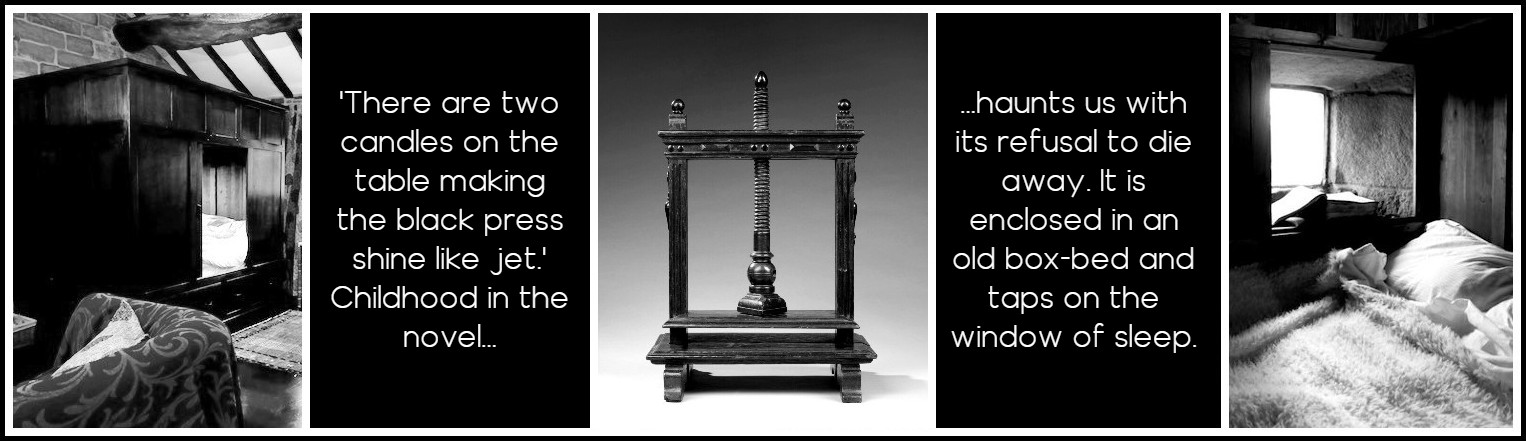

But as the novel proceeds, it is as if the solid objects themselves took on a quality of strangeness and intense meaning. Seldom in fiction has household furniture acquired such aura. For the dresser will be repeated in the text, as an interior. Through the eye of Cathy’s bewitching diary in Chapter III, we glimpse ‘the arch of the dresser’ curtained off with Cathy’s and Heathcliff’s childish pinafores, a sanctuary from the ‘awful Sunday’, of which odious Joseph makes short work, ripping down the makeshift curtain of their privacy. But this was over twenty years ago. In Wuthering Heights, present precedes past in narrative time; then (the dream-ghost at the window) past invades present. ‘In’ and ‘out’, ‘past’ and ‘present’ mesmerize by their apparent dubiety. And the locus of their exchange is the solid object which does not change; which ‘is’, simply, itself, but acquires in the telling of this story a field of meaning. Thus the ‘clothes-press’ Lockwood encounters in Chapter III becomes a mental object in Cathy’s delirium at the Grange in the centre of the novel: ‘There are two candles on the table making the black press shine like jet’. ‘There is no press in the room, and never was’, Nelly asserts, rattled. There is, Cathy knows, and she shrieks out that ‘the room is haunted!’ The novel shifts the clothes-press from the Heights to the Grange and a couple of pages later transports the hallucinating Cathy to the ‘oak-panelled bed’ in which we saw Lockwood lie in Chapter III. Her very self seems to have disengaged from her, establishing itself autonomously between illusion and reality. It’s only a mirror-image, as Nelly says. Cover it up and it goes away. But it is also in a true sense the black press documented by Lockwood. For minds have rooms; we cannot clear them of the furniture of childhood. And childhood in the novel haunts us with its refusal to die away. It lifts off the page of an old book; it is enclosed in an old box-bed and taps on the window of sleep. We always contain the child we once were and cannot disown her by the simulation of adult identity, status and manners.

The Box-Bed, Ponden Hall, Haworth | Linen Press | The Box Bed, Ponden Hall, Haworth

The narrative structure of Wuthering Heights has been aptly compared with a nest of Russian dolls or Chinese boxes, a series of disclosures which are also ambivalently enclosures, insides with the status of outsides. The final interior, being a solid miniature replica of the outside, refers us back the way we came. But is there any ‘center’ at all in this double-bound, ambivalent tale of cloven, mirroring and decentered characters? We must see double. There are two of everything and everyone, a radiating system of doppelgängers bonding each soul with a mate. The two scraps of Cathy’s diary tell of boy-and-girl bonding, mutiny and punishment by separation (that is, splitting). From this origin springs the mighty double cycle of the Wuthering Heights narrative. Published in two volumes, it has two major narrators, encompasses two generations of two families and has two endings, the second being itself double: the marriage of the second generation pair, and the ambivalent destiny of the first, sleeping together and/or walking together on the earth. The design has a rigorously mathematical precision which displays a concern for the evolution of identity in time and through mating and reproduction: its two-generation structure belongs somewhere between Shakespearean tragi-comedy, and an experiment in literary eugenics by a woman who was a keen amateur botanist and zoologist with much experience of practical observation of the life-cycles of creatures, both wild, tame and human.

Andy Warhol, Shadow with Glasses, 1981

Mating, breeding and pedigree are the very essence of a plot which is a breeding experiment in regeneration (the second Cathy, Hareton) and degeneration (Heathcliff, Hindley, Hareton). The contemporary pre-Darwinian watchwords, ‘evolution’ and ‘the survival of the fittest’, have an evident relevance to the eugenic artist of Wuthering Heights who artificially selects the matings which will form successful unions in the second generation, whilst making extinct the Heathcliff line. At the centre of the novel is the death of the eternal child, the maladaptive Catherine in giving birth to the baby Catherine, capable of maturing adaptation: ‘About twelve o’clock, that night, was born the Catherine you saw at Wuthering Heights, a puny, seven months’ child; and two hours after the mother died.’ Cunning and uncanny, the double structure of Wuthering Heights splits the identity to complete it. An exiled Catherine gives place to a homeward-bound Catherine. The lament for exogamy, which exiles the girl in our culture from her first home and self, exploits in a two-generation saga that very mechanism to lead the self home to source, through the inbreeding of cousins whose stock has been strengthened by mating ‘out’. One of the most passionate novels in our language is also a relentless tour de force of complex logical plotting.

Andy Warhol, The Shadow, 1981

The act of reading is generally assumed to be a leisurely and comfortable way of getting ‘in’ to the author’s mind. We say that we are ‘deep in a book’ or ‘I haven’t got into it yet’; or—most appropriate to Wuthering Heights—that we ‘lose ourselves in a book’. We lose, that is, our selves. Most traditional novels hold wide the door, issuing genial invitations to the ‘dear reader’ to enter and share the privileged fascinations of sharing space with the author. Few novels advertise indifference or frank contempt for the guest’s pleasure. In breaking this rule, Emily Brontë demonstrates that ‘Get lost’ augments ‘Come hither’ in arousing a reader’s desire to break in and discover whatever secrets are advertised as being withheld. The pleasure of the forbidden haunts Wuthering Heights by implying that its interior is hostile to trespassers. Gothic antecedents, from Hoffmann’s The Devil’s Elixirs to Hogg’s The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, do not explain this fortification against the reader. Gothic writers prefigure Emily Brontë’s framed narrative device by pretending to disappear into an editorial role. Where Hoffmann is genial, Hogg is severely documentary. In Emily Brontë the fictive ‘editor’ has executed a vanishing-act: executed himself on a literary level, to all intents and purposes. There is no one there to greet and draw us in, save a gauche outsider, the narrator Lockwood, intent on barging into the house of a neighbour nearly equally set on barring him out. The ‘walk in’ was uttered with closed teeth and expressed the sentiment, ‘Go to the Deuce!’. The suggestion that ‘Come in’ signifies ‘Clear off’ is reinforced by the fact that the owner makes no effort to unchain the gate until the visitor’s horse is shoving at it with his breast. The novel begins in sharp, bizarre farce.

Photo: MK. S, Unsplash

Lockwood’s attempts to enter and establish familiarity with the house, its occupants and history figure our own as readers. For in the absence of an authoritative narrative voice his observations not only determine the bounds of our information but mock our endeavour to enter into the book’s depths. This immediately raises a quandary. Whereas in Jane Eyre we lose ourselves in Jane’s ‘I’ and see through her eyes, in Wuthering Heights no such pleasurable surrender is permitted. For although one trusts Lockwood’s observations, his wit is not of the highest. One respects his eye but not his ‘I’. We might say that he spells out what he sees adequately, but reads its meanings indifferently and can react preposterously. In relation to the dogs which guard the interior, his behaviour is not only fatuous but infantile: ‘I unfortunately indulged in winking and making faces at the trio’. This folly arouses the ‘canine mother’ and her brood to leap upon him, barking furiously. Combat with a poker is succeeded by the conquest of the pack by a mighty cook with a frying pan. Within a page, the youth has been rescued by his host and expelled. The chapter is over. He has got in, been attacked and extruded: getting ‘in’ and getting ‘out’ are the sole matter of the plot. Back where he started, in Chapter II Lockwood again launches himself at the house: ‘I don’t care—I will get in!’. Chapter I stands as the ‘penetralium’ of the novel, taking us ‘one step’ in, for the narrator notes that there existed no ‘introductory lobby or passage’ to the house.

Photo: Leonardo Baldissara, Unsplash

The description of the house and access also serves as a metaphor for the text and the terms of our admission as interpreters. Readers accustomed to the polite provision of introductory passages of exposition, leading to the textual equivalent of an easy chair and introductions all round, will be balked. A fiasco succeeds as Lockwood attempts to identify the family and its relationships. Names are strangely hard to come by and, when delivered, baffling. Some names are simply withheld. There is, for example, ‘t’missis’ who Joseph considers unlikely to let him in: ‘Why? Cannot you tell her who I am, eh, Joseph?’ ‘Nor-ne me! Aw’ll hae noa hend wi’t,’ muttered the head, vanishing. The head without a body that promises to have no hand gives place to the ‘missis’ with a teapot who refuses to make tea, a lout with a clenched fist, and a sardonic host who all combine to thwart the incomer’s polite but disastrously erroneous and madly circumlocuted ascription of the ‘amiable lady’ or ‘beneficent fairy’ to host or lout. The atmosphere within the upside-down indoor world in which the squirming visitor begins to feel ‘unmistakably out of place’ has much in common with Alice in Wonderland, and ends with a reversal of the first chapter: Lockwood striving to escape into the snow from this madhouse is held down by two of the guard-dogs. Now he is ‘in’ with a vengeance; but being ‘in’ becomes a form of exclusion (from his right place) and the displaced outsider would get ‘out’ again if he could, but instead must stay the night and go deeper ‘in’. Farce begins to unite with the spectral and uncanny for the outlander who as an incomer pays for his curiosity by confinement in the unknown.

Photo: Chloé Fontaine, Unsplash

CONTINUED IN PART 2 (SEE IMAGE LINK IN ‘RELATED POSTS’ BELOW)

STEVIE DAVIES – THREE NOVELS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments