Emily Brontë

WUTHERING HEIGHTS: DOUBLE-TALK & DOUBLE VISION – PART 2

Stevie Davies

Posted by kind permission of Stevie Davies, novelist, essayist and short story writer; fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and the Welsh Academy; Professor of Creative Writing at Swansea University.

From Stevie Davies, Emily Brontë: Heretic (London: The Women’s Press, 1994) 73-88

THIS IS PART 2 OF THE ESSAY. READ PART 1 FIRST.

Thérèse Lessore, The Daredevils, 1830

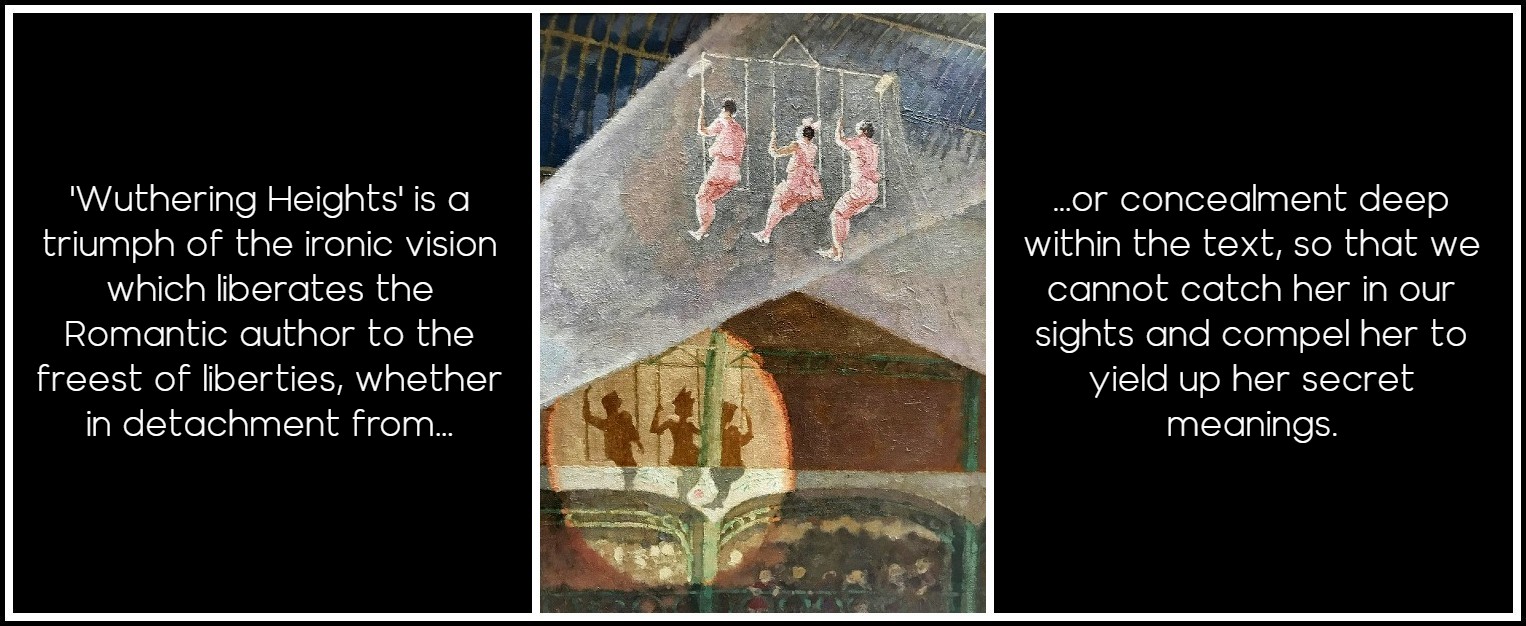

‘Wit’, Schlegel wrote unforgettably, ‘is an explosion of the compound spirit.’ The early chapters of Wuthering Heights, at once single-minded and craftily double, sublimely ridiculous, elevated and bifocal, exhibit that ‘real transcendental buffoonery’ which Schlegel commended as the essence of Romantic irony, seeing novels as ‘the Socratic dialogues of our time’: In it, everything must be jest and yet seriousness, artless openness and yet deep dissimulation. It contains and incites a feeling of the insoluble conflict of the absolute and the relative, of the impossibility and necessity of total communication. It is the freest of all liberties, for it enables us to rise above our own self; and still the most legitimate, for it is absolutely necessary. It is a good sign if the harmonious dullards fail to understand this constant self-parody, if over and over again they believe and disbelieve until they become giddy and consider jest to be seriousness and seriousness to be jest. Wuthering Heights is indeed an exploding novel. It is a triumph of the ironic vision which liberates the Romantic author to ‘the freest of liberties’, whether in detachment from or concealment deep within the text, so that we cannot catch her in our sights and compel her to yield up her secret meanings. And the explosion is generated from what Schlegel calls a ‘compound’ mind. Uniquely, Emily Brontë’s irony represents the complexity of a mind aware of and not intimidated by its own inner conflicts and those of the world outside. Irony, which says one thing and means another, is a close cousin of paradox, which asserts apparently incompatible truths.

Friedrich Schlegel | Emily Brontë

Wuthering Heights recognizes that we live in a world of eternal oppositions, whose strife is so unpalatable to society and individuals that it is blocked out by the psyche in a system of polite fictions. It therefore invites us unceremoniously into a house of multiple ironies which grasp the simplifying visitor by the throat and worry him nearly to death. The structure of dialogue in the Heights is an antiphony of assertions followed by denials, insults generating retaliations, questions balked by sneers. The characters who are all more-or-less hostile to one another as well as to the intruder, speak a common dialect of sarcasm, taunt and threat. In other words, ‘yes’ from the very first almost invariably means ‘no’ or generates ‘no’. If Lockwood is the ‘harmonious dullard’ of Wuthering Heights in whose face its witticisms explode, its dogs snarl, its fists are shaken, he also stands in for a set of attitudes which we as readers are expected to bring to the novel, and must, absolutely and peremptorily, abdicate—literality, rationality, the stable viewpoint of common sense. The antics at the Heights correspond to Schlegel’s ‘real transcendental buffoonery’, for while Lockwood’s vain imagining that Cathy might take a shine to his vapid person and the unfortunate mistake about the pet cats which turn out to be ‘a heap of dead rabbits’ take the form of broad farce, his animadversion to Heathcliff’s ‘amiable lady’ raises a spectre, from an ancient, cold aversion: ‘Where is she – my amiable lady? Mrs. Heathcliff, your wife, I mean. Well, yes. Oh! you would intimate that her spirit has taken the post of ministering angel, and guards the fortunes of Wuthering Heights, even when her body has gone. Is that it?’ Perceiving myself in a blunder, I attempted to correct it.

Yunosuke Sakai, Cats, Unsplash | Graciela Iturbide, Conejos Luna, 1987

Sympathy for the guest as he bleeds slowly to excruciated social death, skewered on the host’s rude wit coexists with that unamiable Schadenfreude with which we watch our fellows flounder in the mire of gaffe. Meanwhile a ghost, the first of many, escapes subliminally from Heathcliff ‘s brutal manner-of-speaking, and invests the house with strangeness. The uncouth and the uncanny meet. The delectable slide on the banana-skin takes the reader skidding toward the underworld, a site of potent threat and magnetism, which it is usual to say Emily Brontë neither affirms nor denies, but might be better described as both affirmed and denied. She is at home in the country of anomaly and self-contradiction, where we with Lockwood must struggle for footing. Irony is an aggressive-defensive posture which means we are possessed by but never entirely possess the work; that sensation of hail-fellow bonhomie which we enjoy whilst reading a good book is denied to the reader of Wuthering Heights. The author seems to take a quite violent pleasure in fortifying herself against us through an irony which serves not only to assert artistic freedom but a full-scale feminist defiance of servile norms. The ‘lady’ is not ‘amiable’.

Fernand Khnopff, Rote Lippen, 1897

Allowing for individual differences, does it make any difference whether the reader encountering this mesh of irony is male or female? The answer to such a question in relation to Jane Eyre would be an unqualified ‘yes’, judging by the generations of young women who have seized on Jane’s pilgrimage as a unique voicing of their own story of female need, oppression, rebellion, conflict and assertion. In relation to Wuthering Heights, the answer must surely be yes—and no; no—and yes. This dialectical answer, aggravating no doubt in equal measure to those who read the novel as an exclusively feminist text and to masculine readers to whom Wuthering Heights is profoundly dear, is not intended as a liberal compromise but as the fullest response this reader can make to the doubly bound extremism of the novel. For while Wuthering Heights is an account of female and male sundering and self-division, centralising woman and making man secondary, it is also a holistic account of male-and-female bonding and identity with one another, which at once opens and closes the breach between the sexes, by referring both back to the unitary source in the lost mother and the mother-world.

Marie Krøyer, Double Portrait of Marie and P.S. Krøyer, 1890

In denying the fundamental opposition of male and female, it is capable of speaking on behalf of humanity as a whole. Virginia Woolf expressed this powerfully when she wrote: That gigantic ambition is to be felt throughout the novel—a struggle, half thwarted but of superb conviction, to say something through the mouths of her characters which is not merely ‘I love’ or ‘I hate’, but ‘we, the whole human race’ and ‘you, the eternal powers…’. The sentence remains unfinished. The novel seems to speak at the genderless level of ‘soul,’ and it speaks for both sexes in the same scintillating but strangely neutral voice of the spirit at fullest stretch: ‘I am Heathcliff’ annihilates the significance of biological and cultural gender distinctions. Yet at the same time, Wuthering Heights is the testament of a woman and recreates the human race in her own image. ‘Man’ in our language covers for ‘man’ and ‘woman’ in a species denominated homo sapiens. Wuthering Heights reverses this bias: ‘woman’ covers for ‘man’, for both emerge dyed in the colours of the author’s female experience, desires and perceptions. Little good it does to either, for each inhabits a world of tragic impairment and forsakenness; once, they were one, but not now, or yet.

Magritte, The Lovers, 1928

However, if the relationship between Catherine and Heathcliff is a displacement of the symbiotic bond between mother and child which acknowledges no boundaries, this bonding must surely be a uniquely precious gift to the male reader of the novel, cut off in our society from his feminine source and ‘those first feelings that were born with me’. Perhaps this is one origin of the intense emotion stirred by the novel: in reminding us how much we have lost, it at once grieves us with the knowledge of our estrangement and restores to us a kindled consciousness of the springs of original life. Simultaneously a violent book, full of exploding people running amok like needy, ungovernable children, and a uniquely tender echo of a pre-conscious union, it remembers a haven which Nelly, and Christian believers, project as a heaven still to come. She phrases this most movingly: ‘I see a repose that neither earth nor hell can break; and I, feel an assurance of the endless and shadowless hereafter—the Eternity they have entered—where life is boundless in its duration, and love in its sympathy, and joy in its fulness.’ Yet this intimation, so harmoniously articulated, dwells in the realm of irony, the dubious ‘yes and no’ of a shadowed world in which we only know that we know nothing.

Gustave Courbet, Lovers in the Country, 1844

The act of reading, seldom entirely passive, is also a dynamic meeting of the book’s mind and our own. German Romanticism had initiated a concept of the active reader, which, as expressed by Schlegel, has considerable bearing on the experience of Wuthering Heights: The analytical writer observes the reader as he is; accordingly, he makes his calculation, sets his machine to make the appropriate effect on him. The synthetic writer constructs and creates his own reader; he does not imagine him as resting and dead, but lively and advancing towards him. He makes that which he had invented gradually take shape before the reader’s eyes, or he tempts him to do the inventing for himself. This very modern appreciation that books generate readers, who in turn complete the text by entering into its meaning, has a profound relevance to the creativity of Wuthering Heights. There is no single narrative ‘I’ with which we are invited to blend or seduced into surrender, but rather a sequence of different ‘I’s telling and interpreting parts of the tale—Lockwood, Nelly, various servants, Isabella, Heathcliff—the effect being to provoke, excite, stir and quicken the imagination of the reader into dialogue. A rhythm of attachment and detachment is set up as my reading ‘I’ assents to and dissents from the of Nelly or Lockwood. Sometimes, swept into the narrative, we forget the framework altogether, only to be reminded by an aside, or the temporary cessation of the story as the narrators pause for sleep or to chat or quarrel amongst themselves.

Marilyn Monroe reading James Joyce’s Ulysses, Long Island, 1955 | Photo: Eve Arnold

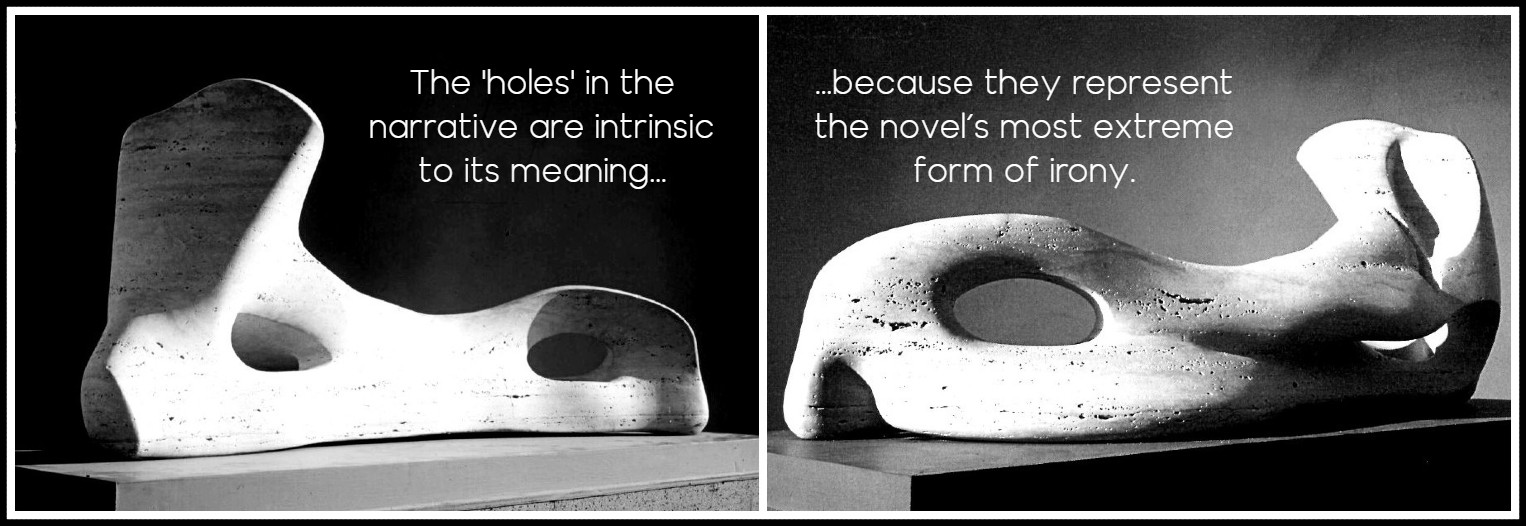

Wuthering Heights ‘tempts the reader to do the inventing’ for herself, because its deepest experiences take shape in the realm of problem, to which the novel denies authoritative solutions. This invention for oneself is not quite the same as the practice of ‘reading-in meanings’ so often and understandably deplored. We all come to Wuthering Heights with bees in our bonnets, and the novel seems to have a wonderful power to agitate the hive, which swarms with ‘solutions’ to the riddles and problems it opens up. Hence a Marxist closes the open question of Heathcliff ‘s origins by supposing him to have been a destitute Irish orphan; another problem-solver detects through a series of authorial ‘clues’ an illegitimate son of Mr Earnshaw. However thought-provoking such suggestions may be, they signal our distress at the thought of living in the realm of the unknown and inconclusive. Originlessness hurts. The ‘holes’ in the narrative are intrinsic to its meaning because they represent the novel’s most extreme form of irony. You can throw whatever speculations you like into them—‘Who knows, but your father was Emperor of China, and your mother an Indian queen’—and they will remain empty holes, zones of quandary and curiosity connected to the novel’s and to life’s most profound questions about where we come from and where we are going. Emily Brontë creates a reader who enacts on the literary level the search of the characters for one another over the borders of mortality. As Heathcliff head-charges the universe, so we cudgel our brains against the text’s provoking unaccountability.

Henry Moore, Reclining Figure: Bone, 1975

Wuthering Heights records, mocks and arouses the polarities of fear and desire in its readers. But it locates these opposites in the same place. For we all want to get ‘in’. But once in, we automatically want to get ‘out’ again. The sanctum is also a prison, a motif repeated rhythmically through the novel. Even the enclosure of one’s own person involves an anchorite’s mortification. To Cathy who needs an identity outside herself in Heathcliff, ‘an existence of yours beyond you’, the body becomes a ‘shattered prison’, somewhere outside which lies a glorious world. The novel records and structures a dread about the self. It splinters, halves, displaces and aborts identity: the core interior of a person may be empty or haunted. Climbing into the box-bed and shutting the lid upon this inside-of-the-inside, settling down for sleep, Lockwood finds that he has enclosed himself with a terrible stranger, his own self, in fact: I slid back the panelled sides, got in with my light, pulled them together again, and felt secure against the vigilance of Heathcliff, and every one else. The ledge, where I placed my candle, had a few mildewed books piled up in one corner; and it was covered with writing scratched on the paint. This writing, however, was nothing but a name repeated in all kinds of characters, large and small—Catherine Earnshaw, here and there varied to Catherine Heathcliff, and then again to Catherine Linton. In vapid listlessness I leant my head against the window.

Courbet, Le Désespéré, 1843 | William Etty, A Bacchante, 1835

Oddly, the inside-of-the-inside, where Lockwood feels so ironically secure, abuts on to the outside, for inside the box-bed one wall is window. This paradox resonates throughout the novel. The sleeping self in its supposed sanctuary, resembling the unborn in utero and the departed in panelled interment, is assaulted by spectral outsiders violently demanding entrance. The mind is not, as Milton’s Satan bragged, ‘its own place’ but an ill-defended fortification, intruded upon by the writing on the sill or in a book, its unconscious an alien world in which one does not feel oneself. The uncanniness increases as Lockwood becomes (like us and on our behalf) a reader of texts, and through his reading discovers that this narrow space he occupies was inhabited before by a treble stranger—Catherine Earnshaw… Catherine Heathcliff… Catherine Linton—whose raw and vehement testament he reproduces on the page, displacing Lockwood’s consciousness. Her text superimposes itself on his, as he has invaded her bed-space. Now indeed we, the readers, feel that we have reached the ‘inside’ of the novel: An awful Sunday!… I wish my father were back again… I took my dingy volume by the scroop, and hurled it into the dog-kennel, vowing I hated a good book… I reached this book, and a pot of ink from a shelf. So vividly authentic is the energy of the childish voice, with its burning resentment, determination and neediness (‘we cannot be damper, or colder, in the rain than we are here’) that these meagre scraps of salvage are enough to conjure up the whole complex dynamic of a family group. And this ‘innermost’ story concerns breaking out (the joint ‘rebellion), shutting in (incarceration in the back kitchen), breaking out again (‘a scamper on the moors’) and shutting out (Heathcliff’s ejection from common meals and play).

Caspar David Friedrich, Woman at the Window, 1822

All writing invades our minds with other presences and voices: to read is to be temporarily ‘possessed’, the droning ‘I’ of self displaced by or assimilated to the ‘I’ of another. Our minds lie in another’s place, rather as the narrator spends his nights in the dead Cathy’s bed, not once but twice, for much later Nelly remarks to Lockwood that he is recuperating from his illness in the same bed at Thrushcross Grange ‘where you lie at present’ as that in which Cathy had spent her time as an invalid. Dreams like maladies may be catching. Emily Brontë shows how haunting all writing is, as the reader-narrator dozily transferring attention from marginalia to sermon, falls asleep and is galvanized by his twin bad dreams, the violent chapel-service and the dream of the child-Catherine at the window. Now Lockwood, deeply immersed in himself, dreams of entrance and exit, the dismaying interface between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’. In the first dream he is wandering outside. How can he get into his home? Joseph advises breaking in with a weapon; but, no, it is not home at all but the chapel, from which the ranting preacher excommunicates him and he suffers public rejection; in the second dream, a ghostly, homing girl knocks and begs for entrance(‘Let me in – let me in!’), which he denies. Awakening, out he comes as Heathcliff comes in. Comically, the haunted Lockwood now ‘haunts’ Heathcliff, visiting on him the garbled tokens of his dreams in the mad denunciation of his host’s maternal ancestor: ‘Was not the Reverend Jabes Branderham akin to you on the mother’s side?’. Such fatuousness has something of the sublime about it: it bursts forth on the hither side of wisdom and has its roots in the inchoate depths of the unconscious mind.

Odilon Redon

The text comprehends the coherent incoherence of dreams, their bipolar functioning, and the urgent displacements and dislocations through which they must transmit the singular doubleness of their deepest truths. Lockwood may be a bit of a fool. He is in this respect one of and with us, bourgeois book-buyers or borrowers. But his unconscious mind is no fool at all. It recognizes the motherlessness of Heathcliff, his changeling status, and connects at the deepest level, though with absolute reluctance, with the storm of desire, violence, grief and loss which centers at the Heights. It works overtime to decode the scrambled messages of the night. The Heights story penetrates Lockwood and opens the locked cabinet of the self, just as the novel pierces into the recesses of the reader. For we too may have longed for the return of the dead; that the borders be breached which seal them off from our view: Heathcliff ‘s invocation ‘Come in! come in! Cathy, do come’, framed in the doorway in the chamber of his isolation, represents that desire. At the same time, the return of the dead is our greatest nightmare, represented in Lockwood’s ‘Begone! I’ll never let you in’. This double attitude of terror and desire is split between the two persons; there are two dreams, a ‘male’ one of Jabes and a ‘female’ one of Cathy, each self-sealed implacably against the other, yet mutually necessary.

Odilon Redon

This duality is the essence of Wuthering Heights whose world is founded in irreconcilable oppositions, doublings and divisions. We must somehow mate them into meanings we can tolerate: a Linton and a Cathy must breed a Cathy Linton, a Hindley and a Frances must unite into a new Earnshaw. Out of Lockwood’s double dream scrambles the progeny of a half-witted brain-child: ‘Was not the Reverend Jabes Branderham akin to you on the mother’s side?’ Half a wit is better, perhaps, than none. In this motherless novel, the question of Heathcliff’s orphan-state shimmers through the farce and horror; the all-important question of origins, where we come from and how to get back. Lockwood now makes his way back as best he can, staggering through the pathless snow where drifts obscure the guide-posts, and reiterates his loss of self by ‘losing myself among the trees, and sinking up to the neck in snow’, reaching civilization half dead with cold. In three chapters, Emily Brontë’s equivocating vision has cast doubt on all interpretation by removing the bearings and assumptions that distinguish self from other, ‘in’ from ‘out’, past from present, the dead from the living. She has set us adrift in the region of the unaccountable, with such virtuosity that we want more.

Odilon Redon

Nelly Dean, the second (but primary and inner) narrator, bustles round setting all to the semblance of rights. A well-read local housekeeper, gossip-stocked, and a sharply observant eye-witness, she should be ideally placed to mediate events and understanding to the reader. Within a couple of pages she has tidied and tied up all the relationships at the Heights which had Lockwood reeling. The inbred solipsism of the marriages between the two houses comes into relief, with its matings of cousins. This is an inclusive and exclusive world with its own dynamic. And Nelly was there from the beginning: we begin to feel more secure, having a grip on the ‘inside’. All will be explained to our satisfaction. In fact Nelly, who doubles the narrative voice and maintains a dialogue with Lockwood intermittently, is herself an equivocator, riven with unacknowledged contradiction. A respectable Christian busybody whom one could imagine badgering Satan himself to read his Bible and be a good boy, Nelly is also superstitious and heretical, asserting the ‘old religion’ of nature in women’s songs, spells and craft; her judgements oscillate between common-sense, orthodox morality, spite, sympathy and utilitarian rationalism.

Helene Schjerfbeck, Self-Portrait, 1885

Foster-mother to the novel’s children, she serves and fosters the narrative from an ambiguous and unstable position between insider and outsider. The degree varies from her phlegmatic or sourly ironic aversion to the romantic excesses of the protagonists (‘It was enough to, try the temper of a saint, such senseless, wicked rages!’) to a choric plaint of great, tragic power, Biblical or Greek in quality (‘I felt that God had forsaken the stray sheep there to its own wicked wanderings’), to a deep and maternal sympathy for the vulnerable children in their sufferings, especially ‘Hareton, my Hareton’ and the second Cathy. At the same time she manipulates the plot she articulates, often deviously. Her voice, at once implicated and disinterested, belongs to a narrative agent who is a concisely characterized and fairly ordinary person, but with a considerable range of styles at her command—domestic, heroic, pastoral, satiric—all linked by a kind of anonymity through which the voice of the author whose range of register is symphonic may be heard like a ghost. Though it is usual to deny that Emily Brontë is ‘present’ in the narrative, that is not strictly accurate: Nelly’s powerful modulations of tone and mood, symbolism, tight control and elliptical thrust of telling all declare but do not disclose the author. The creator is a fugitive presence without body, location or first person expression—a dispersal amongst dispersals, in dialogue with all the conflicting parts of the novel, resolved on one thing: never unequivocally to resolve the debate. Emily Brontë haunts us like a displaced person.

Emily Brontë

As if in ballad or folk-tale, Nelly introduces the advent of the ‘cuckoo’ Heathcliff into the Earnshaw nest: ‘One fine summer morning…’. The outsider is imported from Liverpool, ‘a dirty, ragged, black-haired child’, age unknown, name unknown, language ‘gibberish’: an ‘it’ not a ‘he’ or ‘she’, produced as if by parthenogenesis from old Mr Earnshaw’s coat. That, hateful pronoun ‘it’ dehumanizes and depersonalizes, rejects the intruder and puts him on the margin between male and female; and Heathcliff is ‘it’ fifteen times over before Nelly’s text accepts and denominates ‘him’. His ejection is the universal aim, for ‘Mrs. Earnshaw was ready to fling it out of doors’ and Nelly ‘put it on, the landing of the stairs, hoping it might be gone on the morrow’. The flare of fratricidal passion between Hindley and Heathcliff introduces the Cain theme whereby the males strive to kill or cast out. The anomalous intruder, so bonded to the father and Cathy, so branded by the antagonism of her brother, is eternally ‘outside’ even when nominally ‘inside’. But the private bond with his foster-sister creates a new ‘inside’-outside’ society: ‘they forgot everything the minute they were together’. Sabbath-breakers and law-breakers, they flourish like little savages on the moorlands in a commonwealth of two.

Joshua Reynolds, A Child Asleep, 1782 | Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Master Bunbury, 1781

Ironically it falls to the child Heathcliff to displace Nelly as narrator by recounting the visit to Thrushcross Grange which marks a vital stage in the trauma of severance. Gaping in through the window at the (to them) palatial splendour of the interior, they are joint outsiders, comically ‘planted’ ‘on a flower-pot’, where for a poignant moment their joint beatitude, at peace with one another in shared interest, contrasts ironically with the demeaning behaviour of the squabbling Linton children framed in the window. When Cathy, bitten by the guard-dog, is taken in, Heathcliff, stigmatized as an ‘ ‘out-and-outer’ is warned off. Now he is alone on the wrong side of the window (excluded and parted) which is also the right side of the window (the moorland side). Giving the narrative to the child Heathcliff, full of defiance of the Linton pretensions and ardent in devotion to Cathy, makes his voice the inside-of-the-inside for a space, framed within Lockwood’s transmission of Nelly’s narrative. The outlaw mingles his ‘I’ with the reader’s ‘I’: We laughed outright at the petted things, we did despise them! When would you catch me wishing to have what Catherine wanted? or find us by ourselves, seeking entertainment in yelling, and sobbing, and rolling on the ground, divided by the whole room? Whatever brutality he may in future commit, we have hauntingly been within him and shared his inner world, understood the suffering of his childhood from outside (Nelly’s account) and within. With the return of the silken, polished Cathy in her acculturated state, her self lost in the drama of her attire, the reader shares the humiliation of the ‘dirty’ boy, and his mortification as, by one of a chain of plot ironies the cleaned-up Heathcliff runs smack into the derision of Hindley, precipitating the hurling of ‘a tureen of hot apple-sauce’ at the delicate Linton.

Mary Beale, Portrait of a Young Girl, 1681 | Antonio Mancini, Lo Scugnizzo, 1880

Linton and Heathcliff polarize against one another: dark and fair, wild and civilized, worker and gentleman, ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’. Although it is in fact more complex than this, since each pole of an opposition in Wuthering Heights itself contains oppositions (e.g., the ‘tame’ Linton children intent on tearing a dog in two; the ‘wild’ Heights children a cooperative unit of solidarity), the narrator displays Linton’s and Heathcliff’s natures as a dynamic antipathy incorporating the universal oppositions upon which nature, human nature and society are dialectically constructed in the novel. As ‘one came in, and the other went out’, Nelly describes the contrast as resembling ‘what you see in exchanging a bleak, hilly, coal country for a beautiful fertile valley’. If these two geologies divide the natural world between them, together they create a totality. For while the arable lushness of the second is more pleasant and fruitful, the spartan uplands bear minerals just as needful and staple (coal) and not without their own raw beauty. The juxtaposition of these two landscapes implies such totality: the whole world stretches between them, and it is as if each makes possible the quality of the other. As hills imply valleys, and are defined by them, so the essential binariness of Wuthering Heights now begins to make itself felt through natural symbolism of great beauty and resonance in a system of antithesis – hill/valley, lightning/ moonbeam, fire/frost, ‘the eternal rocks beneath’/’the foliage in the trees’.

Stanbury, Yorkshire

A dualism derived from German Romantic philosophy builds the tension between Linton and Heathcliff into a powerful image for the whole doubly bound Creation. Schelling had shown that contradiction was essential to life, for ‘Without contradiction there would be no motion, no life, no progress, but eternal immobility, a deathly slumber of all powers’, but those opposites which in God harmoniously coincide in eternal totality, on earth are mirrored in the ceaseless conflict of incompatibles. That is our tragedy. Emerson phrased this perception memorably when he wrote that: An inevitable dualism bisects nature, so that each thing is a half, and suggests another thing to make it whole; as, spirit, matter; man, woman; odd, even; subjective, objective; in, out; upper, under; motion, rest; yea, nay. Because each thing implies the other, the boundaries of twin opposites are put in doubt: the affirmed ‘yea’ implies the denied ‘nay’, the hill the valley, male female, Heathcliff Linton. These opposites are bound into the structure of the Wuthering Heights universe. One must have both. But ‘as one came in the other went out’. In this prosaic clause of displacement, not only the whole tragedy of Cathy but the tragedy bound into the human situation is uttered. One must and will have both; but only one at a time is available.

Photo: Nik, Unsplash

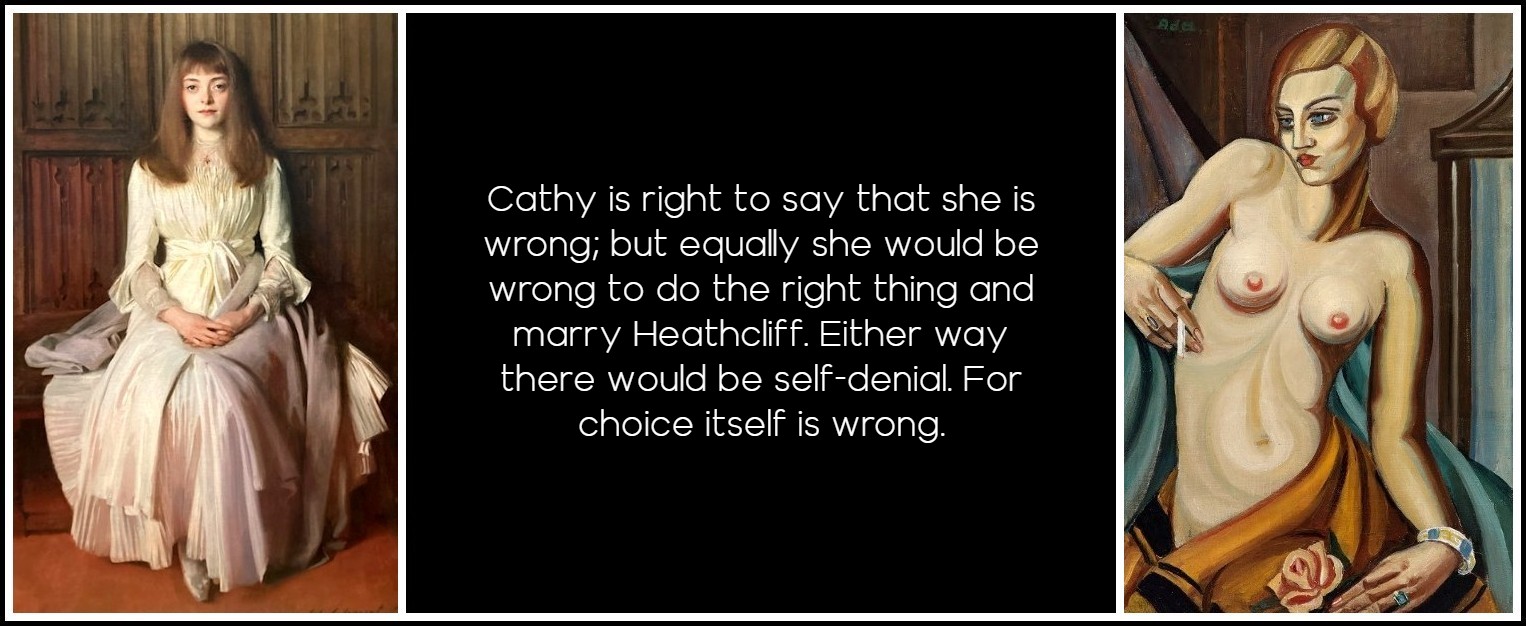

Schelling solved this problem for God by stating that He experiences double time simultaneously, so that His No and Yes can be said together, in meaningful synthesis. For man it is sadly otherwise. The necessity for choice between alternatives is a social requirement. And because, as Schelling and Schlegel both believed, each individual is also binary, the mind composed of twin hemispheres, its will and desires double, Catherine must go on, inexorably in the succeeding chapter, to cleave herself in two to the root, in choosing Linton over Heathcliff, all the while nagging at Nelly to ‘be quick, and say whether I was wrong!’; ‘I’m convinced I’m wrong!’. Cathy is right to say that she is wrong; but equally she would be wrong to do the right thing and marry Heathcliff. Either way there would be self-denial. For choice itself is wrong. But we are so unequivocally bound into the world of equivocal oppositions that choice is imperative. The self is fatally sundered from itself (or its opposite, which implies the self).

John Singer Sargent, Miss Elsie Palmer, 1890 | Ada Peldaviciute-Montvydiene, Nude with a Cigarette, 1934

CONTINUED IN PART 3 (SEE IMAGE LINK IN ‘RELATED POSTS’ BELOW)

STEVIE DAVIES – THREE NOVELS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments