Self-Harm: Cutting

SELF-HARM: CUTTING

Between Mother and Daughter: An Endless Tearing Away?

Fanny Dargent

Fanny Dargent, psychoanalyst, teaches at Université Paris VII Denis Diderot. From Fanny Dargent, ‘Entre mère et fille: un arrachement sans fin?’ in Revue française de psychanalyse, 2013/2 Vol. 77 pp. 415-426. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

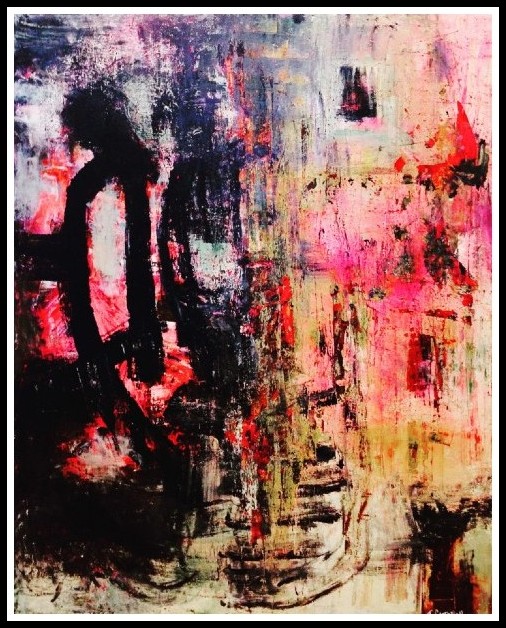

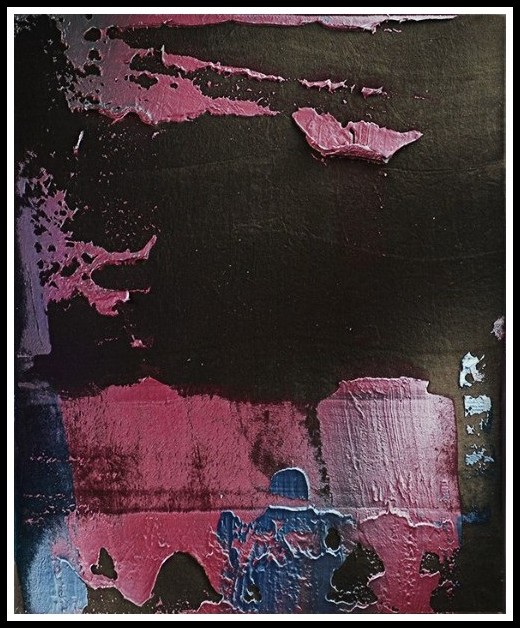

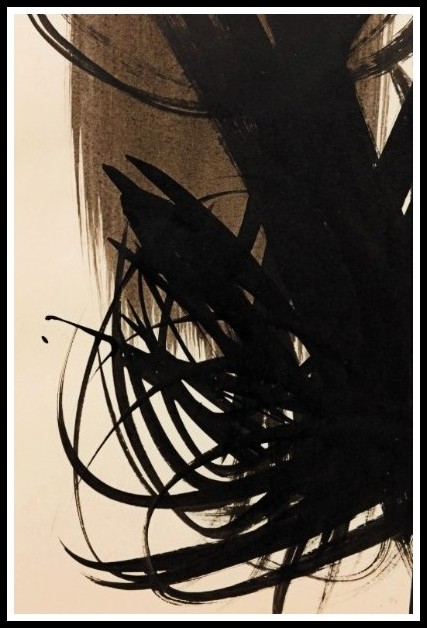

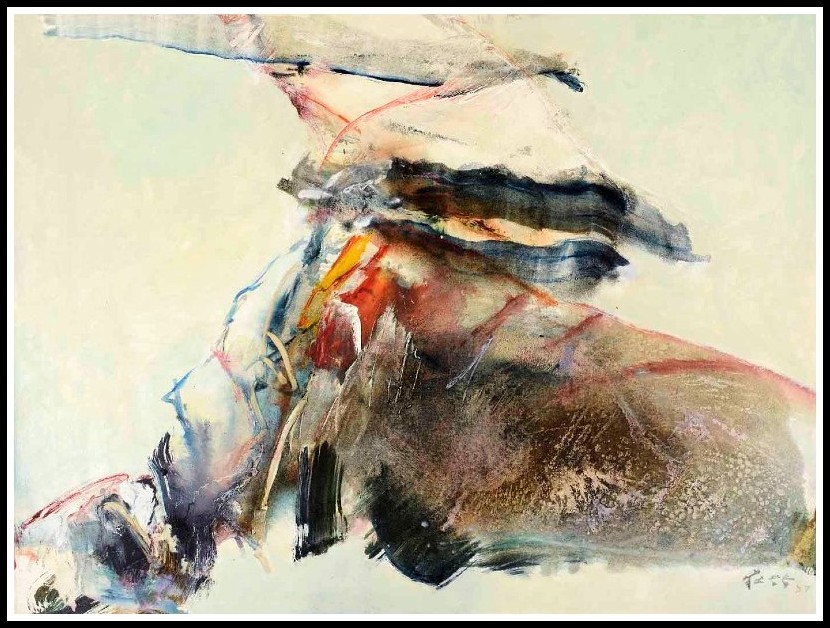

Tommaso Fattovich, Delirio en Carretera, 2021

I. JUSTINE: A DIS-FIGURED BODY

PHOTO: Above a bucket that catches the blood, two hands, fingernails glossed with dark-red polish, cut the wrists with a razor.

PHOTO: A girl in a bathtub writes ‘I love you’ in blood on the wall.

PHOTO: A band of white over the breasts; the rest of the body, naked, splattered with blood.

PHOTO: Breasts in a black bra; on the body, a hand writes with a knife, ‘play with me’.

Tommaso Fattovich, The Fragile, 2019

These photos are accompanied by fragments of poetry focused on suicide. Justine (is it her in the photos?) posted them on her blog. I met her (she was fifteen at the time) during an interview at the hospital where she was being treated. She was also seen by a youth worker, the person to whom she had given the address of her blog. Troubled, the youth worker passed it on to me. And thus it was that I found myself in the position of voyeur, at once disturbed and sorry: disturbed by the mixture of crudeness and distress that the blog expressed; sorry about our inability to create for Justine a space for speech. Indeed, despite the malaise apparent in her blog and during her visits, she refused all dialogue. Whether in a one-on-one interview or when accompanied by her mother (her father has been absent all her life), she remained silent, or spoke only to fall into greater silence afterwards.

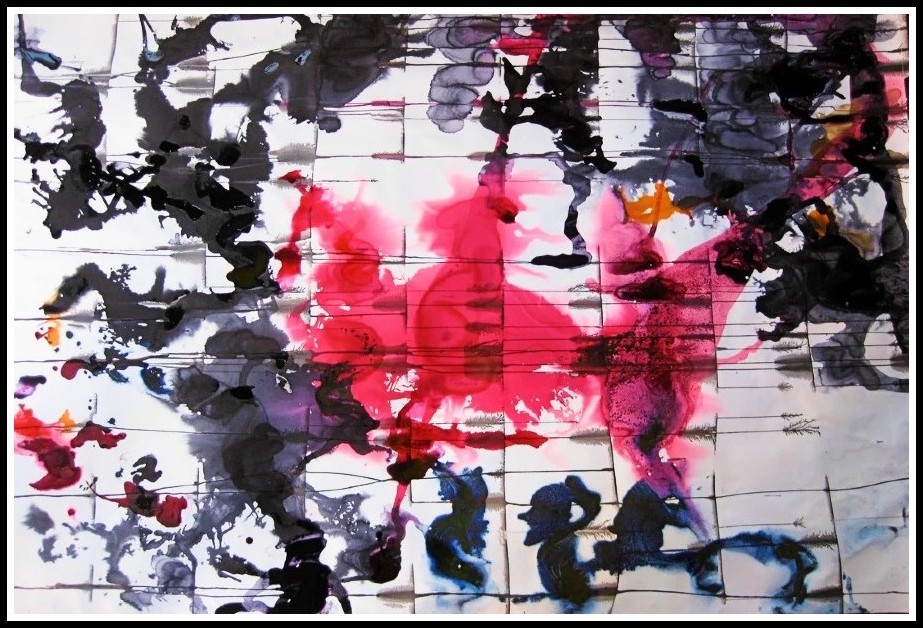

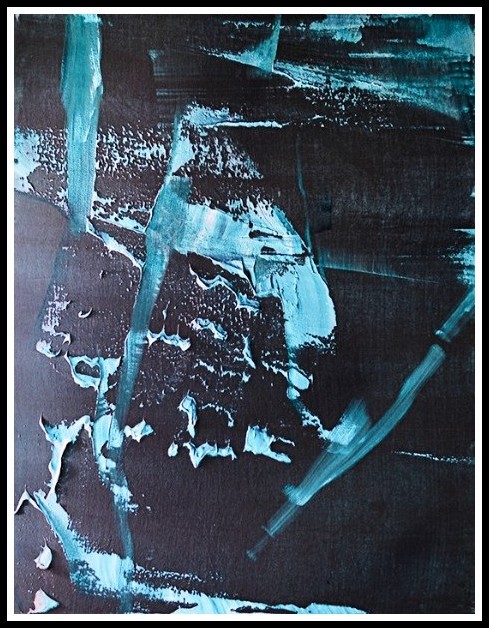

Tommaso Fattovich, Gravity Drops, 2019

Are Justine’s photos a half-perverse, half-tragic instance of acting out underpinned by a call for help? Or are they simply the work of a teenage girl creatively using new technology to express the upheavals of adolescence in all their anguish and exaltation?

Tommaso Fattovich, Goodbye Horses, 2019

In Justine’s mise en scène of a body without a face, we find a condensation of sexuality and cruelty. Her photos give an idea of what she is trying to express as well as what she is trying to escape from. She presents a de-faced, dis-figured body driven by relentless drives, a body in search of identity and recognition. By transmitting these images via her blog, Justine wagers on being found—or not. Indeed, the appeal to the other via the virtual world implies being seen by vast numbers of people—or by no-one. The fact is, between these two extremes, Justine cannot make a place for the other in the reality of a one-on-one encounter. What she does is preserve the anxiety around her while remaining in hiding, a paradox memorably interpreted by Winnicott: ‘It is joy to be hidden but disaster not to be found’. Working with adolescents gives Winnicott’s formulation a singular therapeutic richness. Indeed, to be understood (to be desired, in effect) becomes, in adolescence, as troubling as to be abandoned. To speak of the future is as painful as to speak of the past. To resort to the body, to the act of cutting, is an emergency solution when the intermediation of dream, play, and free association is unavailable.

Tommaso Fattovich, Somewhere, 2015

For two years, Justine’s care would be provided by personnel from school, psychiatric hospital, and state-run social assistance services. Given the prospect of separation of mother and daughter—demanded and feared in equal measure by both—the family situation had become untenable. It was proposed that Justine be sent to a boarding school. Relations between mother and daughter consisted largely in screaming and invective. The mother, between ‘forgetting’ appointments and justifying her behavior by saying she speaks with her daughter at home, proved very difficult to mobilize. After these two years of chaotic care, with the caregivers reduced to speaking more with each other than with Justine and her mother, the mother mentioned she intended to separate from her partner, the father of her ten-year-old son. ‘The two of us will have to move abroad’, she said. The two of us? Mother and daughter. Separate without separating, stick to the familiar and the same, the better to confront a foreign land. A foreign land, for this woman of Spanish origin, could just as well be the Spain of her mother as an unknown country to which she has no ties.

Martin Reyna, Paisaje, 1995

If the tie that binds Justine and her mother—‘not with you, not without you’—is one I frequently come across in my work with teenage girls who cut themselves, how are we to think of the fact that, whenever the compulsion to tear away supersedes the unthinkable separation, the attack on the body appears to take place somewhere between mother and daughter?

Martin Reyna, Untitled, 2009

In girls who cut, the passage through adolescence comes up against the maternal link that impedes the relation to the mother as ‘other’, at once rival and model in fashioning an identity as woman-to-be. Therapy with these girls, as well as with young women who, as teenagers, attacked their body, has enabled me to see that cutting is associated with stumbling blocks in the process of constructing sexual identity. As the continuing strength of the maternal link makes transference onto a sexual object other than herself difficult, the girl displaces the transference onto her own body. This persistence of a predominant emotional investment in her own body is tinged with extreme ambivalence. It takes place instead of, and to the detriment of, the erotic activity of thought. In sum, it constitutes a resistance to the processes working at a solution ‘outside of’ adolescence. The main stumbling block, then, is the refusal of loss, the loss that alone is able to bring about the representation of a body-for-pleasure. [Cutting is an attempt at self-cure, an attempt to bypass the stumbling block encountered in the process of constructing sexual identity. RJ]

Martin Reyna, Untitled, 2012

Often, girls who cut are going through puberty in a family marked by break-ups, with a singular complicity between mother and daughter. The daughter’s puberty creates a shock wave that the mother feels intensely, entailing a regression for the mother that may reach as far back as an infantile position, insufficiently worked through, with her own mother. Daughter and mother then unite in a narcissistic withdrawal that is both protective and devastating, often accompanied by a disqualification not only of the father but of men in general. It is protective thanks to the reassurance of sameness; it is devastating because, confronted with the threat of the incestual, hate alone enables the maintenance of their bond, the bond that is as deadly as it is vital.

Martin Reyna, Terraza, 2011

François Richard has highlighted what is at stake, unconsciously, in this hate between mother and daughter. ‘Though it may be ferocious’, he writes, ‘it assures a strange cohesion. The mother seen as bad by the daughter will always be available for criticism. The daughter does not run much risk of being dragged into an absolute negativity, because the mother is seen precisely as the person one must not take after. Hate here is true hate, not a switching of love into its opposite’. Like a lightning rod, the attack on the body neutralizes excessive excitation while enabling both the counter-cathexis of the violence of the internal world and the preservation of the links to the object in actuality. In this sense, more than expressing hate, cutting dissolves it. The hate in question is cold and desexualized. It aims at preserving a maternal object seen as both vital for the girl’s narcissism and threatening in its intrusive potential.

Martin Reyna, Rouge, 2020

II. MARKING THE DIFFERENCE

Closeness to a single, often fragile mother incurs the risk of dissociation, in that the unconscious regressive desires addressed to the maternal object stand a chance of being fulfilled. ‘A child is being raped’, to borrow Monique Cournut-Janin’s expression, could be the tagline of the phantasy that underlies the bond uniting mother and daughter when the desire for regressive passivity addressed to the pre-Oedipal mother meets the upheaval of puberty, entailing the risk of incestual madness.

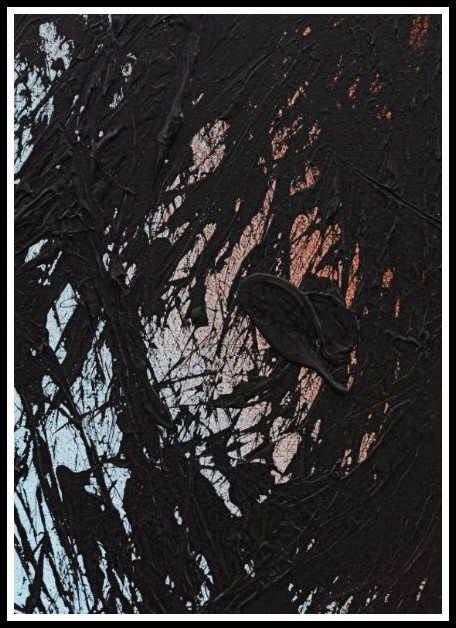

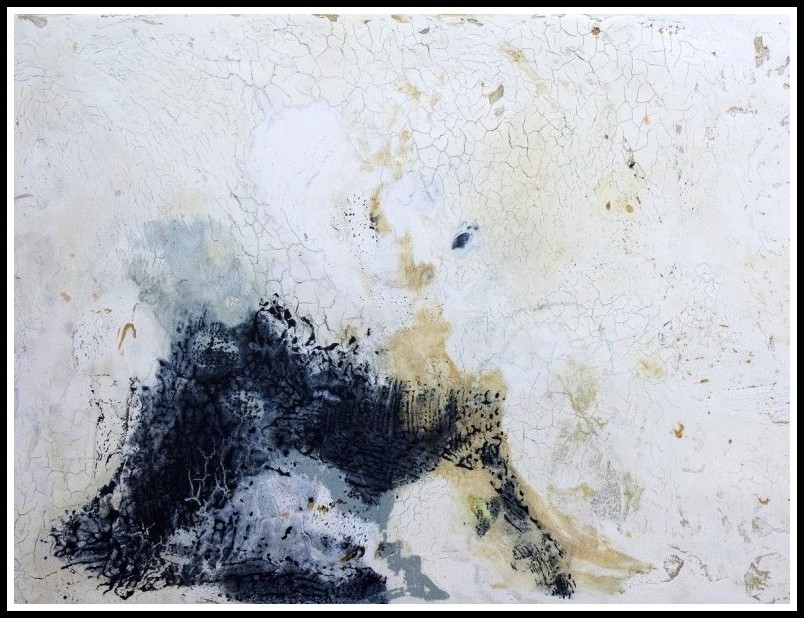

Rémy Hysbergue, A39320, 2020

In this fierce struggle between mother and daughter, we must distinguish between intrusion and penetration. Intrusion evokes the experience of mastery by an ideally omnipotent maternal object, while penetration implies genitality underpinned by incestuous representations associated with the father. The difference resides in the way the intrusion of the maternal object (‘the excess of mother in oneself’, as J.-B. Pontalis puts it) contaminates psychic activity itself. To think, to displace, generates a distance that counters the desire for mastery over/by the object. The phantasy of intrusion is expressed through the feeling of being unable to have a thought of one’s own. It lodges in a cruel, ‘glaringly conscious’ superego that, because the interdiction concerns thinking and feeling, impedes the erotic movement of thought.

Rémy Hysbergue, A40620, 2020

This phantasy, ‘a child is being raped’, paralyzes psychic movement and eclipses its Oedipal version, ‘a child is being beaten’. The sadomasochistic organization regresses to a narcissistic identification. The desire for mastery over the object reverses terms to become a feeling of being dominated, a feeling that is violently intrusive and paralyzing yet necessary to the girl. The body, as the only ‘investable’ form of psychic functioning, becomes the prime locus of a deathly cathexis. This severely restricts the possibility of a ‘talking cure’, since the intense struggle between ego and object crowds out all else in the transference.

Rémy Hysbergue, A40120, 2020

Mother-daughter incest is less representable psychically than father-daughter incest, even though the representation of feminine homosexuality is more socially acceptable. The absence of penetration diminishes the border between tenderness and sensuality, relegating the relation, thanks to repression, to a union akin to the mother-child model. At the cost of anxiety about seduction-penetration, the incestuous phantasy representations concerning the paternal object protect the girl from incestuous mother-daughter conviction. This formulation, no doubt debatable, highlights the difficulty certain girls have in holding a benevolent maternal imago at the same time as a representation of maternal femininity, one that would lead to identification with women. It is always the woman who disappoints and frustrates, not the mother who, for her part, tries to protect the daughter. An idealized, non-sexual mother who, however, is contradicted by the genital sexuality puberty makes the daughter aware of, thus undermining her narcissistic idealization. The mother’s mastery over the daughter will lodge itself at the heart of this conflict.

Remy Hysbergue, A39720, 2020

For Justine, separation became a necessity, given the enormity of the anxiety and the risk of dissociation. The danger lay in the proximity of the maternal object that brought together narcissistic incestuous conviction and perceptible reality: ‘see-touch’ could come to replace ‘talk-do’.

Remy Hysbergue, A40920, 2020

The attack on the body, in this context, is a compulsive reaction, an emergency gesture that paradoxically attacks the borders of the ego as much as it reinforces them. The power of the counter-cathexes (it is always surprising to hear that physical pain is not felt) shows the failure of repression. It is likely that in adolescence all forms of attack on the body serve to neutralize incest in the face of regressive desires induced by contact with the maternal body. Mother-daughter incest (fundamental incest’ according to anthropologist Françoise Héritier), underpinned by ‘the threat of the identical’, demands extreme measures in response: between daughter and mother, attacking the body marks the difference. Disfiguring the body is an attempt to reappropriate it for oneself. Note also in girls who cut the absence of any protective projection: maintaining an idealized image of the maternal object is necessary for the girl’s narcissism, and so that object cannot be designated as responsible.

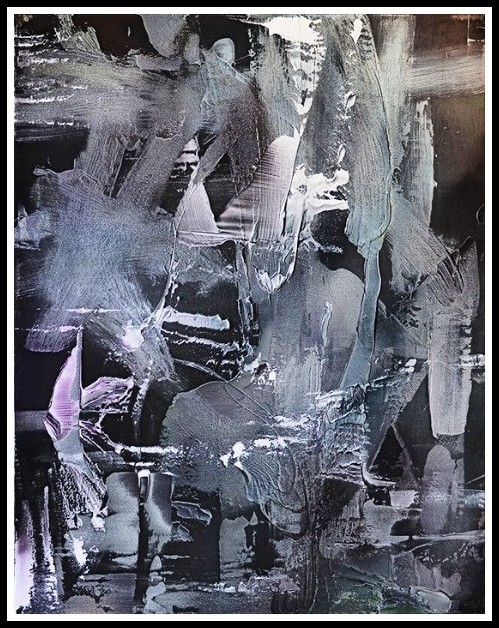

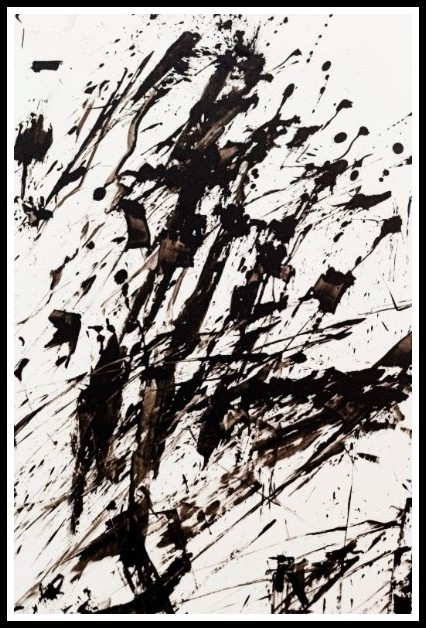

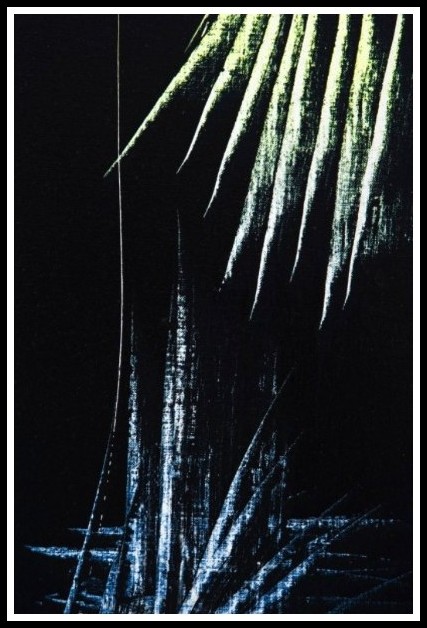

Hans Hartung, Untitled, 1958 (detail)

Only suffering, in its dimension of innocence, is acceptable. Recourse to practices of incorporation (Philippe Gutton, Sexualités), similar to the tendency to excorporation (André Green, On Private Madness), is the only way of protecting against excitation and anxiety when mental working through becomes impossible. This incorporation-excorporation regime is similar to the failure of the evacuation process, an effect of the frustration of the ‘auto’ principle highlighted by René Roussillon. Compulsive behaviours such as bulimia, drug addiction and cutting are the most widespread symptomatic expressions of this. At once rejection and acceptance, they paradoxically try to both tear away from and maintain fusion with the mother.

Hans Hartung, Untitled, 1985 (detail)

Treatment for girls who cut is usually offered on an emergency basis. Hospitalization, sometimes with readmission after discharge, is often necessary, and a multi-pronged approach is generally required. It is quite rare for cutting to continue beyond the period during which the girl is under the sway of the object, or more precisely, under the sway of what she feels she must never lose sight of and must never let be lost to sight. If the act-cum-symptom cedes quickly, its disappearance indicates nothing more than a loosening of the link to the cruel superego or, to put it another way, a resurgence of psychic auto-eroticism. The resumption of dreaming is a common sign of this, as is a change in the nature of discourse during the psychoanalytic session. Even if these two phenomena are evident, however, there is no assurance of psychic change concerning the critical processes of separation and construction of sexual identity. What is at stake in adolescence—to bring about the coexistence of infantile sexuality and the new sexual current—requires, in the case of girls who cut, patience in the therapeutic process, a patience that implies steady, if slow, progress.

Hans Hartung, T1983-E36, 1983 (detail)

III. ONE SEX FOR TWO

Having presented, from the height of adolescent turmoil, this first clinical experience, I will now present a case that illustrates what Freud called Nachträglichkeit, an ‘afterwardsness’ that is still waiting to be dealt with. Putting these two cases in perspective enables us to investigate, through the prism of the mother-daughter bond and the appeal to the body, the avatars of the processes involved in the emergence from adolescence. Therapy with a 23-year-old woman, an ‘extended adolescent’ who engaged in cutting and was hospitalized for it during her teenage years, has lent support to my idea that the processes at work in attacks on the body during the post-puberty period continue well beyond the end of these attacks, crystallizing the refusal to renounce the maternal object.

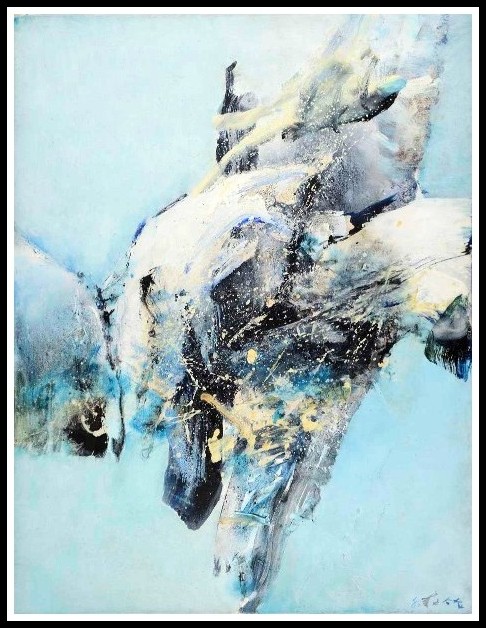

Chuang Che, Untitled, 1986

Indeed, for this young woman as for other women I’ve treated, the end of self-harm and suicide attempts during puberty has not diminished the persistence of a painful attachment to the mother. Beneath the apparent ability to cope emotionally and professionally as an adult, the adolescent passion has remained intact. This young woman, who had compulsively abused her body, continued to maintain with it, now that she was engaged in adult sexuality, a relation characterized by hate, rejection and unease. Thanks to my experience with her, something became clearer in my understanding of attacks on the body that counter-cathect the risk of dissociation, a risk run in the face of the confusion between genital sexuality and the paradoxical pleasure (jouissance) to be had in the struggle with the primary object.

Chuang Che, Untitled, 1987

IV. MARINA: THE ADOLESCENT IN THE ADULT

Marina has a history of hospitalization and psychotherapy. As she was quick to tell me during our first session, she always ends her therapy abruptly—due to the failings of her therapists. That, as I saw it, was a reiteration of a long-standing demand, and it put me on alert for the inevitable frustration of her expectations to come. ‘I want to be happy’, she told me during our first session, ‘a mother who gets on well with her children, not a depressed mother’. Marina has a job and lives with her boyfriend. It is the problems she is having in her sexual life that motivate her return to psychotherapy: ‘Below the waist, it’s just a blank. Everything is in the head.’ Crude images persecute her, pornographic images of penetration, while she forces herself to engage in sexual relations in order to avoid all ambiguity, as she puts is, between her idea of a couple and a mere bond of friendship.

Hans Hartung, T1975-H32, 1975 (detail)

If she no longer cuts herself, Marina invokes the idea whenever she is overcome by anxiety. The representation of an exciting seducer-father was always in the foreground of her seduction fantasy until, one session, the image of her naked mother emerged. It recurred again and again in a series of dreams—obsessive, provocative, penetrating—and contrasted with the image she’d carefully cultivated of a mother devoted to a suffering daughter, complicit in a shared pain. During another session she evoked the link between her first experience of orgasm and the blocking of her sexuality. She was unrecognizable to herself, she said, and then the dream of the night before came back to her, featuring her mother, naked, her breasts—are breasts sexual? she wondered—then declared that in the dream ‘it was my mother’s body and it was me’.

Hermann Nitsch, Splatter, 1986

When the daughter cannot free herself from the sway of maternal seduction, Joyce McDougall’s luminous expression, ‘one body for two’, is more accurately rendered, I believe, as ‘one sex for two’. For many weeks, Marina would dream of her mocking, seducer-mother and her naked, persecuting body, exposed obscenely. Sometimes, however, she would also laugh about it, as when, recounting a dream, she assimilated her mother running naked in a field to a streaker in a stadium. In a darker tone, she then evoked her embarrassment at being the object of men’s sexual gazes. The confusion and blurring of boundaries experienced by Marina has its roots in the persistence of a seductive maternal imago that overwhelms her; she tries to free herself from it by plunging into an adult sexuality that, however, only rekindles the confusion between orgasm and the paradoxical pleasure (jouissance) derived from the fierce struggle with her mother in childhood.

Jutta Naim, Mimesis II, 2017 (detail)

The fascination for the mother’s body, the vividness of the fantasy of seduction, is complicated, for the little girl who’s become an adolescent, by the anxiety of sameness. Indeed, if the daughter has to tear herself away from the seducer-mother, she also has to tear herself away from her alterity. It is when the ‘alterity of the same’ fails that the body is attacked: ‘one body for two’ becomes the threatening ‘one sex for two’, throwing the girl into the incestuous conviction of sameness. Cutting her skin is the teenager’s attempt to tear her body away from her mother’s, yet at the same time it paradoxically maintains fusion with it.

Hermann Nitsch, Untitled, 2012

It took a long time before Marina could accept and be relieved by an interpretation. One such occasion was when she remembered the pleasure she would experience as a child in hearing her mother evoke how little she, Marina, would eat, like a bird; she forced herself to forego a second helping for fear of hearing her mother say, ‘Ah, you see—’. I finished her sentence: ‘you like it!’. For the first time, Marina expressed her relief; we had developed together a construction that shed light on the active part she took in refusing all pleasure (consistent with the top/bottom, above-the-waist/below-the-waist reversal) insofar as pleasure contradicted the idealized representation of the little girl loved and admired by her mother. At the crossroads of narcissism and sexuality loomed the issue of loss.

Hans Hartung, T1964-H1, 1964 (detail)

‘I thought it was only my father, but it’s my mother too’, Marina would bitterly say, much later, when she was able to recognize maternal seduction. The loss of an asexual narcissistic ideal of the mother-daughter bond facilitated that recognition, which in turn opened the way to a recognition of the woman in the mother. What remained repressed was a representation of the parents together, excited by each other, since Marina continued to position herself as a child excited by the father and by the mother. Behind this situation we find, of course, the primal scene that, because it radically excludes the child, is intolerable to her.

Jutta Naim, Mimesis IX, 2017

Marina was able to use her psychotherapy to renew her commitment to the professional ambition she had abandoned: first that of mid-wife and then, in a related domain, the one she would realize. Having decided that she was well, that she now had occupations that interested her, she ended her psychotherapy. I’m convinced that was premature. She did, however, ask me if she could return, if necessary. Note that over the years of therapy, she had made a point of missing each session that preceded my going on vacation, and she had been deaf to anything I might have had to say about that. She continued to protect me from her hate, confining it to the framework of a lateral transference in her professional life. She will probably continue, elsewhere and differently, this slow progress, before finally learning to separate herself from her mother.

Jutta Naim, Inceptions IV, 2013

IV. TO LEAVE ADOLESCENCE OR TO ‘PREFER NOT TO’

The common theme that runs through time, accompanying the little girl through adolescence and into adulthood, is the wounded body itself. Ensuring a paradoxical continuity in the anguished attachment to the forbidden object, it is not the body’s representation in phantasy, not the castrated feminine body of narcissistic-phallic logic, but the body as an object, at once solicited in its dimension of permanence and rejected in its dimension of pleasure.

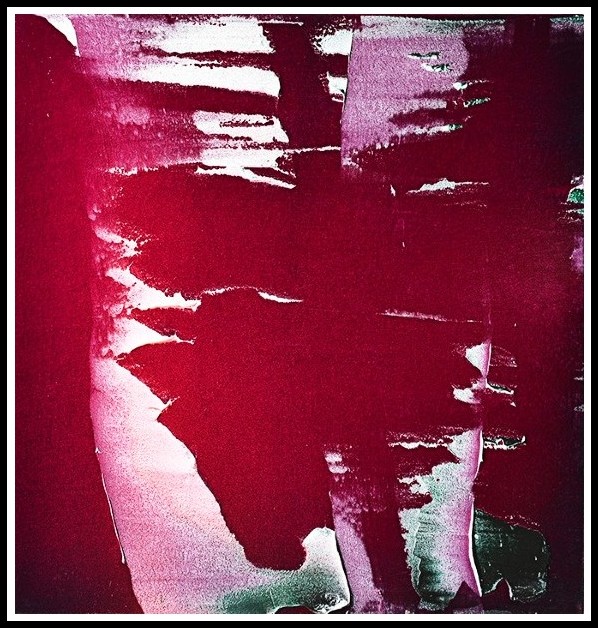

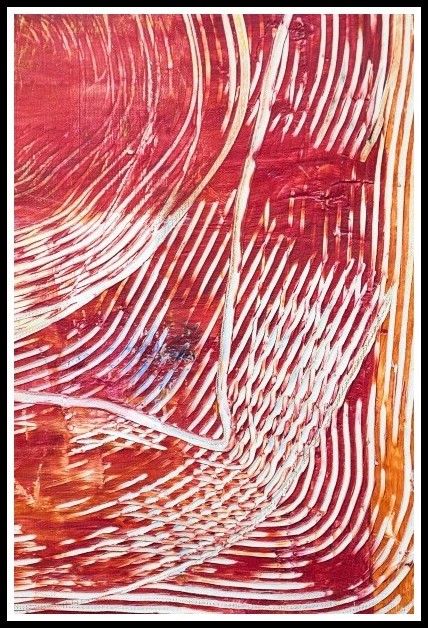

Gerhard Richter, Abstract Painting, 2008

Therapy with girls who cut is a ballet, a tracing of circles from rupture to encounter, from reunion to rupture. If there is repetition at work, each segment enables a shift, a change in the point of view from which the little girl, then the teenager and the young woman, considers herself and others. At a given moment, however, something of what is playing out in the transference is avoided. A tearing away takes place that reinforces the resistance to separation and, with it, the opening to genital sexuality. This something will perhaps await another time and place. The attacked body is as much a foundation stone as a stumbling block, a connecting thread between mother and daughter, a thread that causes pain but guarantees continuity, and so must not be cut.

Gerhard Richter, Abstract Painting, 2006

Hiding behind the attack on the body is the maintenance of the paradoxical pleasure (jouissance) from the fierce struggle with the mother, a pleasure the girl values above all else. What becomes of cutting in the transference? Even though girls who cut are not psychotic, it is the nature of the discourse, the absence of free association, and the difficulty in accepting the terms of psychotherapy that, in this context, best account for the processes involved in the attack on the body. The act of cutting does not substitute for unconscious content, but for the psychic processes themselves. Attacks on the body take the place of what the discontinuity of treatment implies: the shifting from place to place, the girl in one and the same movement tearing herself away from the mother and preserving the bond with her—an endless tearing away that does not stop the girl from living.

Gerhard Richter, Abstract Painting, 2006

Has Marina ‘emerged from adolescence’? This formulation, evoking a purposive idea, is related to two Freudian concepts: the capacity to love and to work, and the convergence of the tender and sensual currents on the same object. As often happens with ‘extended adolescents’, therapy fosters the resumption of subliminatory activity. Sublimation is easier to resort to because, while drawing on the sexual drives, it bypasses the Oedipal conflict that underlies it. This ‘mutation’ or ‘vicissitude’ of the drive finds support in transference love, and in turn supports both the reinforcement of narcissism and the treatment of excess. Children work for the love of their parents; in so doing, they reinforce their self-love via the pleasure they take in their accomplishments.

Gerhard Richter, Abstract Painting, 2006

Excessive corporeal auto-eroticism gives way, in part, to the psychic auto-eroticism of thinking. The intensity of investment in the primary object, for its part, does not give way, though it may shift in line with the narcissistic vicissitudes of sublimation. Emerging from adolescence implies moving towards subjective appropriation of the sexuated body, indissociable from recognition of the other sex. Between mother and daughter, recognition of sexual difference enables recognition of the difference between their respective bodies. To do that, Marina, like Melville’s Bartleby, would ‘prefer not to’. She did, however, recognize that she had chosen her boyfriend precisely because she could treat him as a child, relating to him just as her mother related to her. She found it impossible to imagine she could ever leave him.

Gerhard Richter, Abstract Painting, 2008

Psychoanalyst Jean-Claude Rolland writes: ‘Psychic conflict plays out between the state of infans and a process that is driven by what infans lacks, namely language. Opposed to infans is an adolescens moving towards self-realization, the subject of a psychical movement that reforms the forces and structures which, in the infans state, had remained frozen’. It is at the heart of the sexuated body that that which fails to grasp language and become conflictualized stumbles. The construction of a sexual identity, of the capacity to experience oneself as a desiring man or woman bearing an incarnated language, is closely related to the idea of emergence from adolescence. I say ‘idea’ since nothing allows one to affirm that this process, this ‘emergence from adolescence’, ever has an end. Except, perhaps, the ephemeral illusions that go hand-in-hand with remembering one’s own adolescence.

Gerhard Richter, Abstract Painting, 2008

FANNY DARGENT: THREE BOOKS (IN FRENCH)

FANNY DARGENT

Blessures de l’adolescence

FANNY DARGENT

Les 100 mots de l’adolescent

FANNY DARGENT

La honte: Écouter l’impossible à dire

SELF-HARM: CUTTING IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Four Chapter 4

Low over the bank of earth they ramble, slender, fleshy, needle-like leaves, flashing clusters of tiny crimson buds on dark red bracts. Cracks and fissures run through fragments of fallen bark; from a patch of dry mud, lengths of filament stretch out. Fǣringa! A shock of talons leaps out of the earth, black limbs articulate doom! From coxa to tarsus their movements mesh, until in the grapnel of the spider’s embrace the cicada is clenched. Serrated claws press into the abdomen of the insect; fangs snap out of their groove. Hail! Into the head, between the eyes, fangs sink as venom flows: Into your skin, just below the elbow, you guide the razor blade. Down through dermis and epidermis, down past the capillaries to the dominion of pain, you press the bright steel flake. Around the burning edge a shimmering bead wells up; down the whiteness of your forearm you draw the mesmerizing red. Lifting open a secret trapdoor, the spider enters its burrow; as blood flows in rivulets across your skin, the predator descends with its prey. I stare into the tumult in your eyes; you bring your fingers to my lips. How do we measure the distance between God and man? Twenty-two finger-breadths make the universe: The cubit of your forearm bridges heaven and earth.

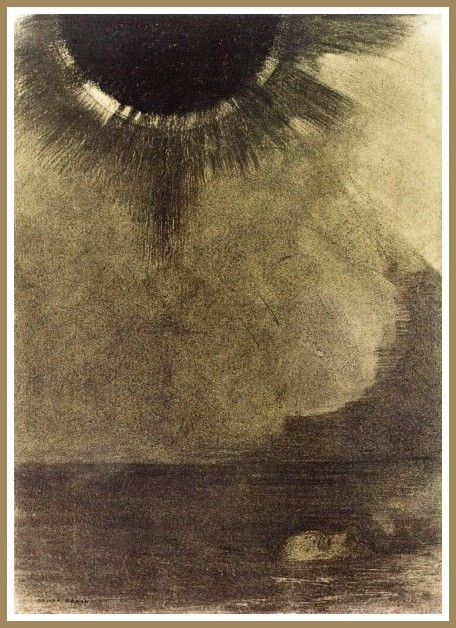

Odilon Redon, Drowned Man, 1887

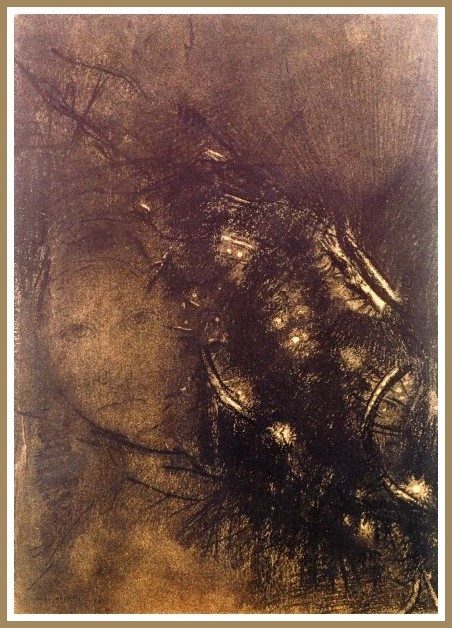

Fǣringa! The capture spiral stretches and retracts: A creature sways in the spider’s web. Sitting at the centre, her legs resting on the radial threads, the spider feels the tremors of her struggling prey. She pulls on the spokes, reading the signals: In the cockcrow hour of the orb, a flickering brightness of flame. The spider approaches the butterfly: Come, into the underworld I will conduct thee. From her spinnerets she pulls a silken shroud and wraps the wandering soul in sleep: Blood from your spleen bangs in your brain for answers that do not come; barren on your tongue, earth dulls your syllables. How can I get it into my head that you’re dead? That your death is irreversible? How can I exist if you don’t? I’d always slept on my stomach in freefall: Now I sleep all curled up and fetal. Fǣringa! The spider vomits digestive juices onto the body of the butterfly: You draw the blade through a wilderness of pain, cutting right to the heartroot. Lush and bright the blood comes, flowing down your forearm. Sharp and focused, the burn of the pain unburdens you of the weight of your feelings.

Odilon Redon, Dream, 1898