ANOREXIA

ANOREXIA: A DESIRE FOR WHOLENESS

Androgyny & Anorexia, or the Desire to Become One Flesh

Patricia Bourcillier

From Patricia Bourcillier, Androgynie et Anorexie, ou le désir de devenir une seule chair (Flying Publisher & Kamps, 2007) pp. 11-13. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Patricia Bourcillier, author and independent scholar, was born in France, studied and worked in Germany, and emigrated to Sardinia. She now divides her time between Beyenburg, Cagliari and Paris. Having read a good deal of the literature on anorexia, I can confidently say that Patricia Bourcillier has written what I consider the finest book on the subject. Her description of the condition is of the same order as Dostoevsky’s depiction of Raskolnikov. Whether derived from a psychoanalytic, historical or mythological perspective, every page of her book scintillates with insights. The following excerpt constitutes the introduction to the book. R.J.

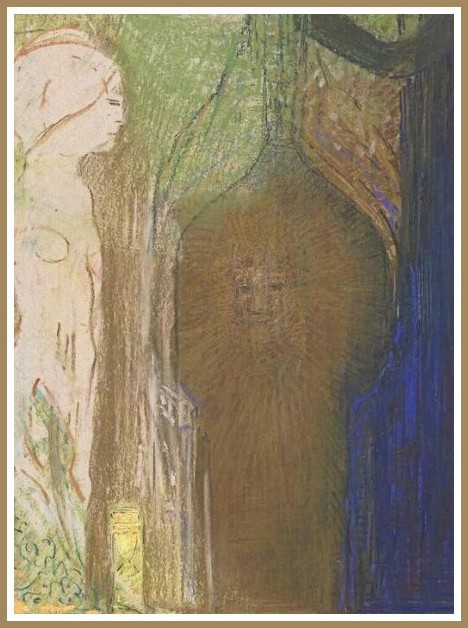

Odilon Redon, Tête de femme, 1875

Much has been written about girls who eat ‘nothing’ because they want to lose weight and become light as a feather, free of all earthly burdens. The meal, however, has always mediated human relations; people eating together is a symbol of communion, sharing and social belonging. Everywhere, throughout history, the shared meal has signified hospitality and conviviality; the sensual delight of eating creates a climate of confidence in which differences can be dissolved. Indeed, as a French saying goes, ‘to eat is to talk with others’. So why do thousands of girls now refuse to eat? Why does the irrepressible desire to ‘be thin’ incite adolescents to a virtual annihilation of the body?

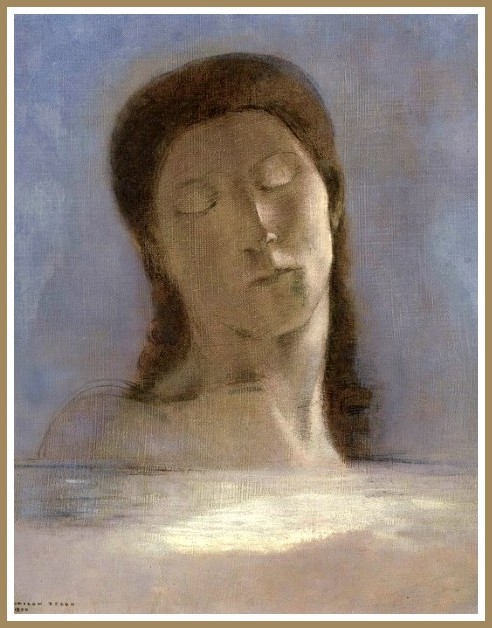

Odilon Redon, Le temps, 1892

‘There is a crisis when it comes to models of womanhood’, says psychoanalyst Eric Bidaud. Girls, lost in their suffering, not knowing what woman to become, go from refusing to eat to compulsive eating. It is not beauty they are pursuing, but identity. There is no doubt that to ‘be oneself’, to ‘return to oneself’, is the issue that recurs again and again, for anorexics believe truth is on the side of the body pure and whole, free from all foreign interference. Hell, not life, is what food evokes for these girls. And thus they return to the source, to the fatal separation that made them creatures of need, in order to be reborn in a body that belongs to themselves alone. So, lying behind the refusal of food we find the inevitable question of origins, with its attendant ideas of death, resurrection and redemption.

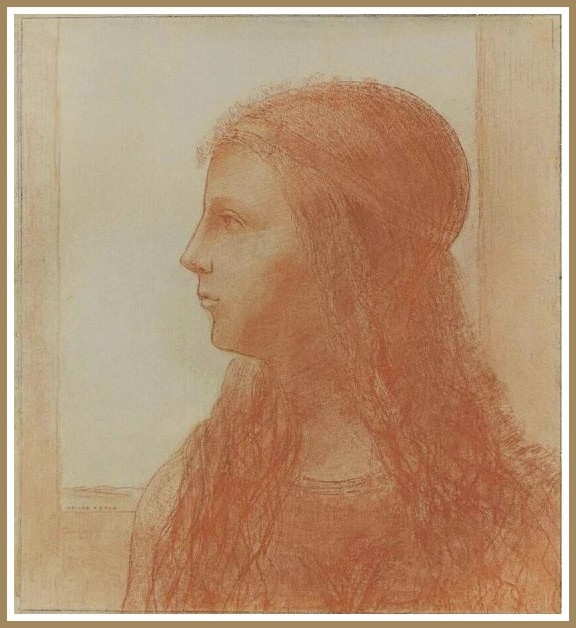

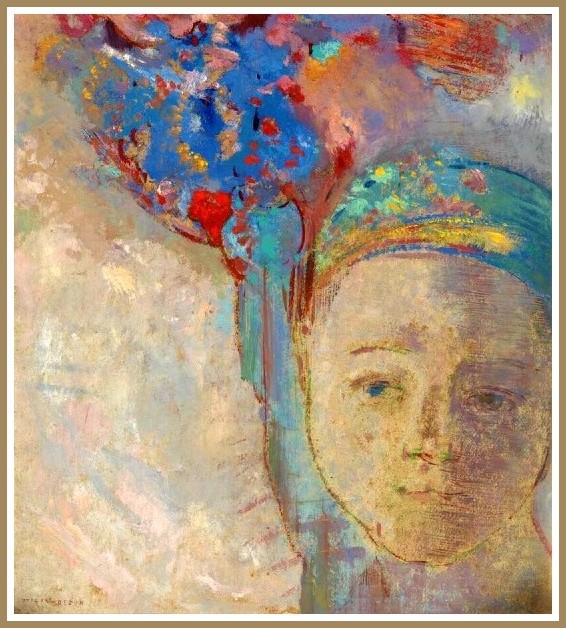

Odilon Redon, Les yeux clos, 1890

In all the monotheistic religions, fasting enables, on a symbolic level, the restoration of a lost unity, the return of spirit and with it, the capacity to overcome death. This need for ‘totality’ engenders the desire to escape annihilation and awaken to a different life, a new phase of development. Thus in anorexia we find, on one hand, an irrepressible desire to stay fixed at a particular phase of development, and on the other hand, a dread of becoming adult, which is really a fear of death. It is not a question of imitating a real or specific ideal of beauty, but rather of expressing, sometimes unto death, a nostalgia for what has been lost: the paradise of asexuality where the sexes have not separated, the place where primitive man is pure, not male but androgyne. A return, then, to a domain outside time where one is eternally young, where no future beckons, where one, in a word, is immortal. This ‘I-alone’—flawless, without otherness—is, as Julia Kristeva puts it, ‘a phallus disguised as a woman’, its phallic law proclaiming the exclusivity of the self and the refusal of any concession, any dependence, any servitude.

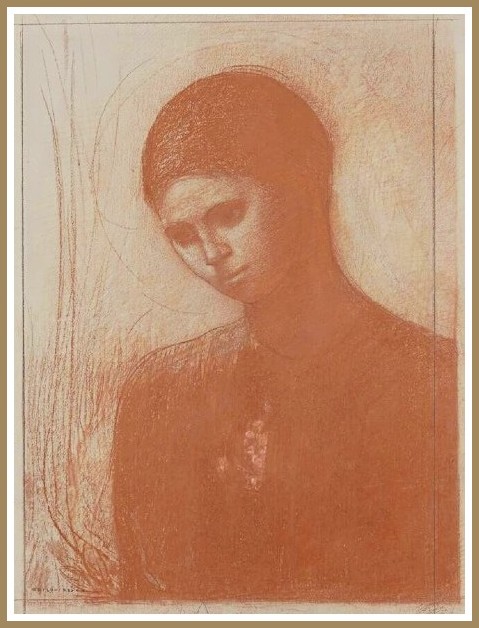

Odilon Redon, Profil de jeune fille, 1890

Today the myth of the Origin, as Bernard-Henri Lévy reminds us, is also the ‘credo of the fundamentalist’, of he who wages war against ‘foreign bodies’ in the name of a ‘will to purity’. As the outcome of this will to purity is, in the worst of cases, death and destruction, women must be made to pay for the crime of having giving birth because, in giving birth, they have destroyed the purity, the perfect ‘totality’, of what remains latent and unrealized.

Odilon Redon, Jeune femme, 1897

Paradoxically, anorexics, like fundamentalists, dream only of ‘union’. Yet in contrast to the fundamentalist who imprisons the other, embodied by women, in a limited social space, thus finding himself invested with sovereign power, the anorexic will erase the other to throw into relief the split body: on one hand, the perfect body—androgynous, idealized, an object of desire, and on the other hand, the real body—sexualized, an object of denial, and what’s more, a ‘foreign body’ in the bubble of the ideal self, the self that must be purified by freeing it of food fecalized from the moment of its ingestion.

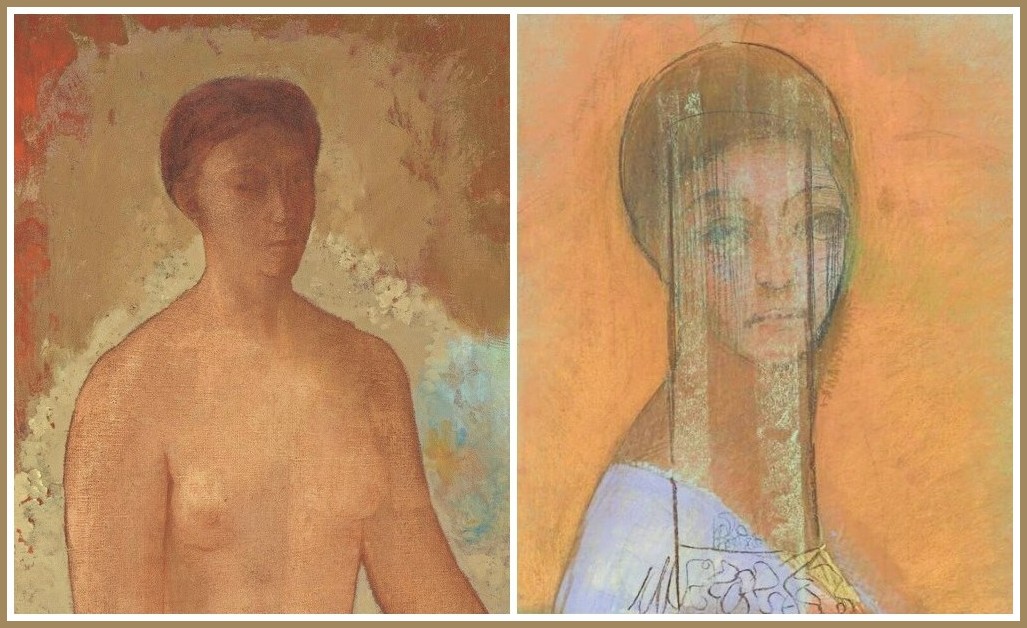

ODILON REDON: Ève, 1904 | Femme voilée, 1897

At the beginning, then, was purity, the imagined purity of the androgyne that Julia Kristeva denounced as ‘the most insidious masquerade of a liquidation of femininity’, separating women from men, excluding alterity, foreclosing the possibility of ‘meeting’ the Other in shared experience.

Odilon Redon, La palme, 1897

Beyond eating disorders, then, the parallel between anorexia and fundamentalism is evident in the shared fantasy of a lost wholeness and the demand that founds that fantasy: an imperious demand for recognition of a ‘true’ identity and ‘equal’ rights, a ‘hymn to truth’ that is in fact a settling of scores, a blind revolt, or a protest against the violence of social relations. And thus arise troubling feelings—not having the same rights as others, being nothing, having no voice, being rejected, forever waiting on the fringes of that ‘blank column’ in which nothing is written, lost in a no-man’s-land where life and death are indistinguishable—feelings that betray an unrecognized quest for grandeur that, inevitably, lead to destruction—of oneself or others—when desperate efforts to conform to the model of the powerful fail.

Odilon Redon, La Cellule d’or, 1893

ANOREXIA IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

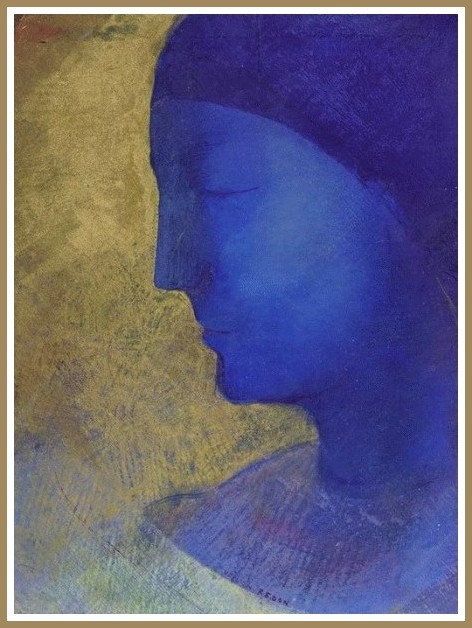

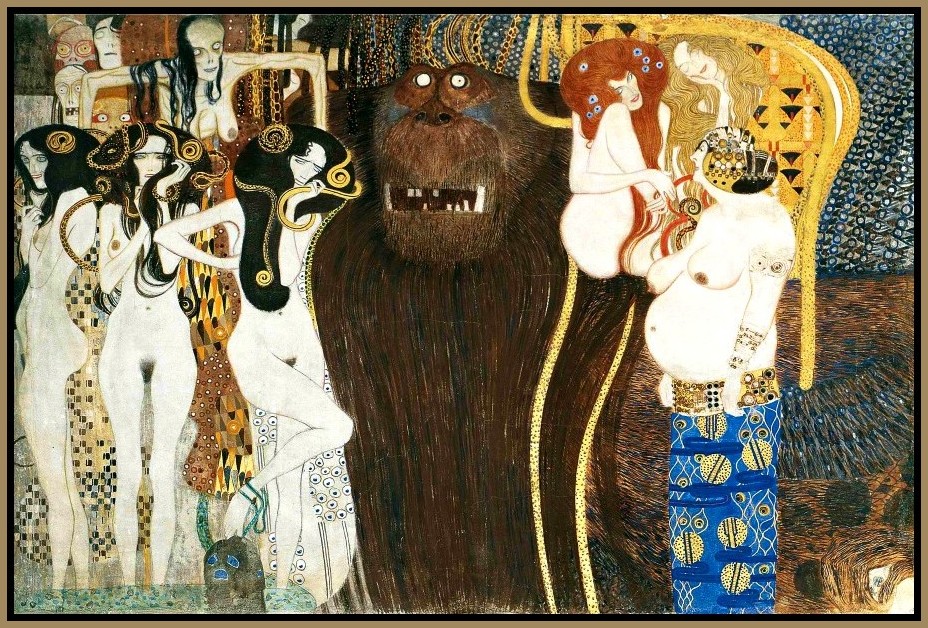

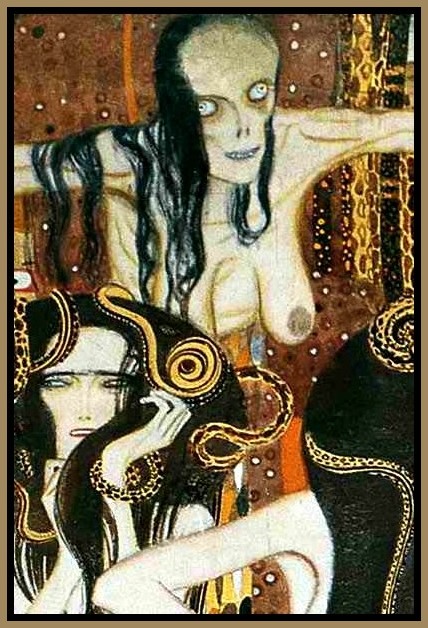

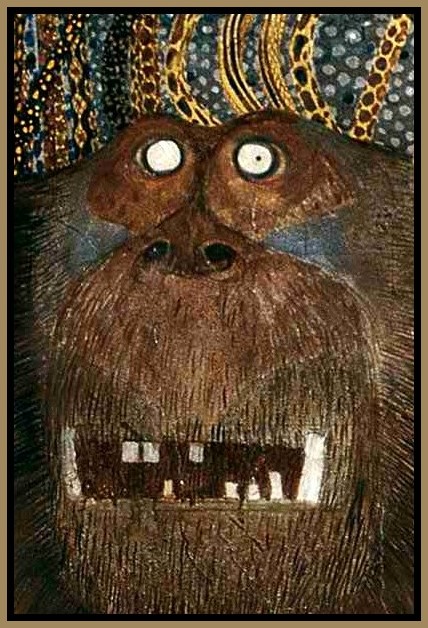

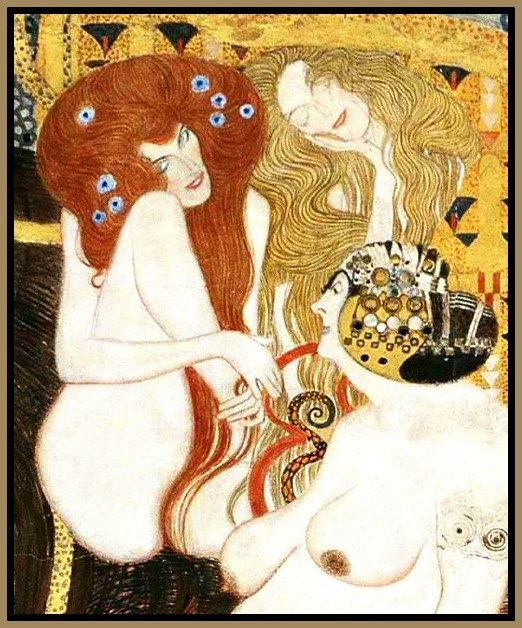

Gustav Klimt, The Beethoven Frieze: The Hostile Powers, 1902

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 1

Gaunt, stark, raw in her nakedness, the girl you once were confronts you. Instantly you recognize her defiant vulnerability and self-subjugation, her vestigial femininity and proud isolation. A wave of tenderness overwhelms you, you feel a kind of homecoming: Never have you forgotten this girl who lives inside you, never has a day gone by without you paying her tribute.

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

The Hostile Powers, 1902 (detail)

Burnt into your face, the embers of your eyes glow with contemptuous sadness. Your hair is falling out, your veins have collapsed; a layer of fine hairs covers your body like a fetus. The spindles of your legs end in swollen ankles; your fingernails are brittle and blue. A skeleton covered in skin, you are a walking corpse, a species of living dead. Jubilant in your decrepitude, you are an affront to the living.

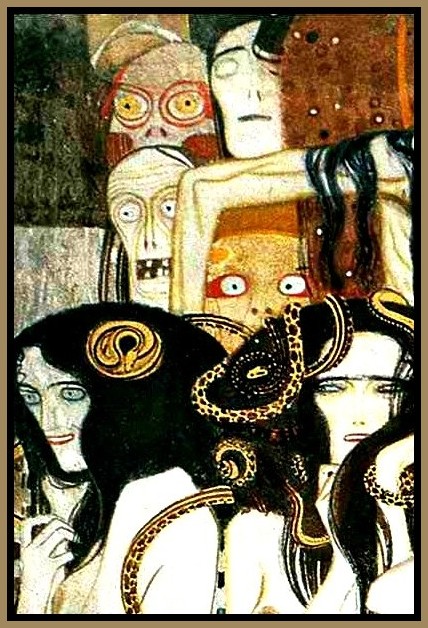

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

The Hostile Powers, 1902 (detail)

Wearing layers and layers of clothes and cradling a cup of tea, you stand by the radiator but can’t get rid of the cold: It lives inside you.

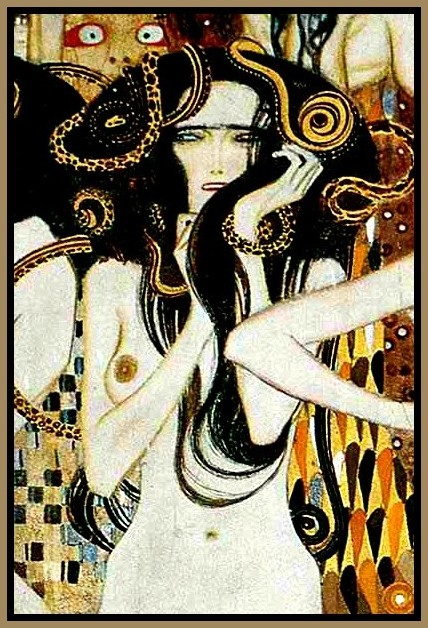

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

The Hostile Powers, 1902 (detail)

Looking at photos of yourself as a little girl, you break down and cry: Was I really like that once? You can’t remember the last time you laughed, you can’t even remember what laughter is like. You’ve lost the feeling of being young, you’re convinced you’ll never recover it: You feel you’ve already lived a lifetime.

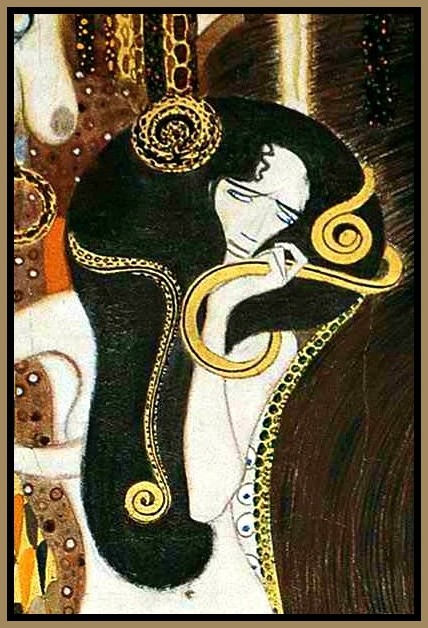

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

The Hostile Powers, 1902 (detail)

A dinner party! For others you make a four-course meal; for yourself you ritually cut a slice of cucumber into sixteen pieces. For others the palate is to be delighted: For you it is to be denied. And so before ingesting any food, you strip it of its potential for reverie by counting every calorie and converting it to grams: Nothing over which you are not master will enter your body.

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

The Hostile Powers, 1902 (detail)

The scales are your touchstone of integrity, you’ve made others understand that, but how can you make your mother understand that you are killing yourself because you can live neither with nor without her?

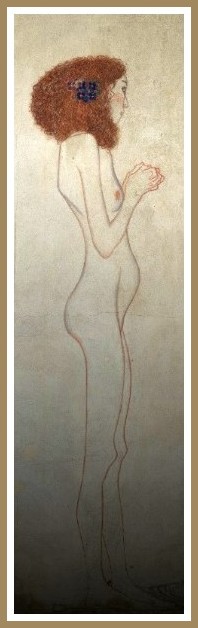

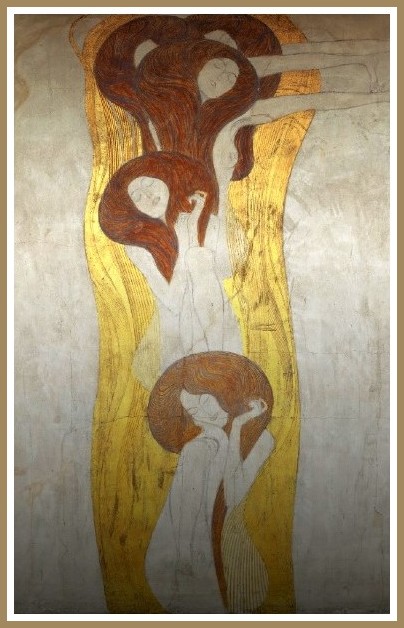

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

The Suffering of Weak Humanity, 1902 (detail)

It never lets up, the force that drives you, it never lets up for even a second: It pushes you to extremes, there’s no in-between. One moment you’re lying unconscious on the bathroom floor, a vein in your eye popped from the violence of vomiting, the next you’re furiously peddling your bike along the lake. One moment you’re crying yourself to sleep, the next you’re devouring Wuthering Heights. And then in the morning you amaze everybody with all you can still do. Up until you were hospitalized, you could do a month’s school work in a week and still be tops in every subject.

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

Appeasement in Poetry, 1902 (detail)

My God, why did I wear white? Your father at the wheel, his new wife beside him and you on the back seat, you make your way home from the Lucerne Festival where, from the turn of the opening trill to the wit of the adagio-presto coda, your performance of Beethoven’s tenth violin sonata had been a triumph: A happiness that would soon belong to another lifetime. Between your legs the stain spreads, dissolving your dream of ambivalence. So red is the colour of reality, so red marks my limits. God, what a cataclysm! Thus you came to understand that the exterminating angel is female; yes, that even for you, the other sex is feminine.

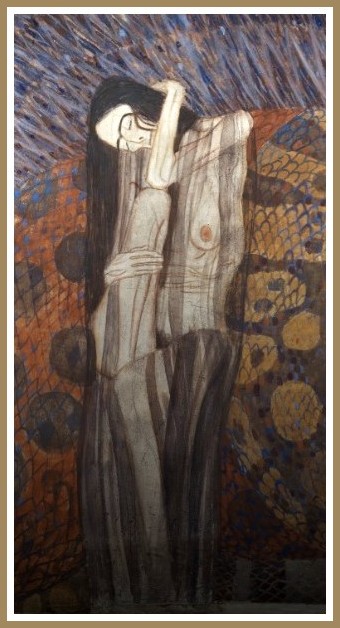

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

The Hostile Powers, 1902 (detail)

Why can’t my body be like a boy’s, profiled for action? Why must it betray me with its loathsome blood and swelling flesh? My body is hollowing out, emptying out, unfolding; my body is scandalous! And all of it aimed at one thing: At making me—my God, never! Never! I don’t want to be a woman: I want to be myself.

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

The Hostile Powers, 1902 (detail)

With this decision you begin your swim to the source, determined to be reborn in a body that belongs to you alone. And so you make yourself immune to others, you remove yourself from everything impure and begin to shed your flesh. Why should you eat? You lack nothing.

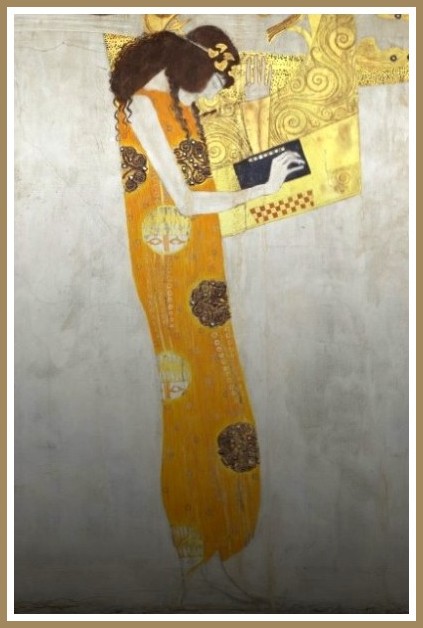

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

Longing for Happiness, 1902

It’s working! What a thrill when the scales testify to your will, what a thrill when your cross a threshold! Before long you’re flirting with death like a matador, convinced that readiness to die allows you to live: In elation you realize that your ideal weight is not thirty-five, thirty or twenty-five kilos; no, your ideal weight is zero!

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

The Arts, 1902

The joy of needing no-one and nothing, why didn’t you think of it before? Accepting neither reasoning nor coercion, neither love nor interest, you declare yourself sole judge of who you are and recognize no link to anyone. You need starvation to live, you’re in complete control—no one will take that away from you! What do they know, thinking you were trying too hard to please the opposite sex? The fools—if they only knew you were putting an end to sex itself! Why can’t they see that in your infinite nostalgia you are hungry for something else? No, it’s all or nothing. You will make no concession, you will not be reduced to servitude! No!

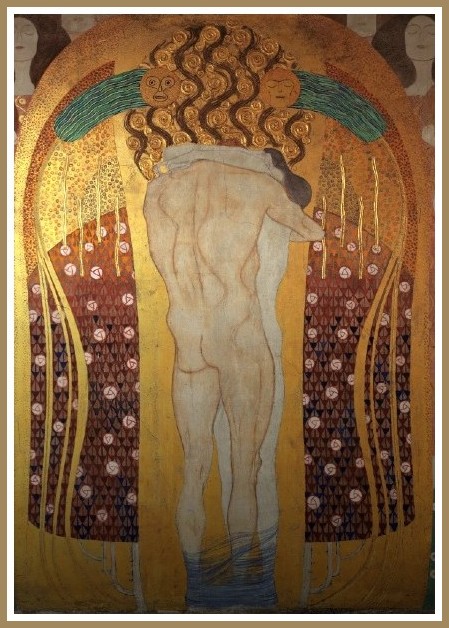

GUSTAV KLIMT, ‘THE BEETHOVEN FRIEZE’

A Kiss to All the World, 1902 (detail)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

Treating an Anorexic – Case Study: Lydia

THE ISOLATION OF THE ANOREXIC: A LIMIT TO OMNIPOTENCE

Brigitte Le Cozannet

Brigitte Le Cozannet, psychoanalyst & family therapist, formerly at Hôpital intercommunal de Villeneuve-St-Georges (France), now in private practice. From La lettre de l’enfance et de l’adolescence, 2002/2 (no 48), pp. 77-81. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

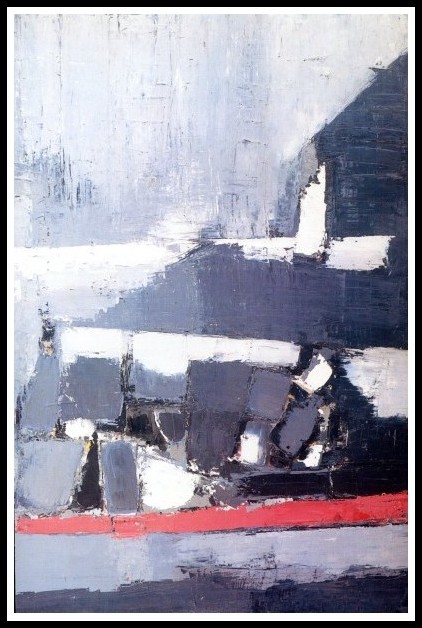

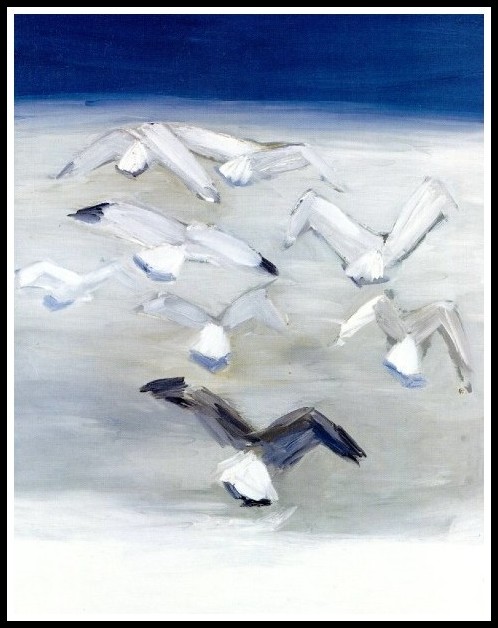

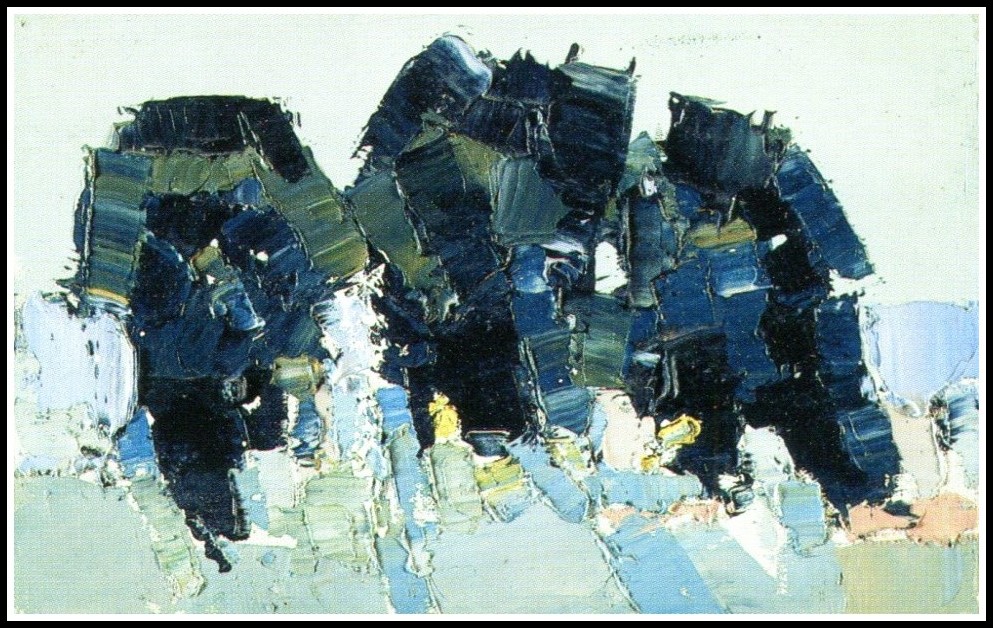

Nicolas de Staël, Ballet, 1953 (detail)

I. ANOREXIA

For the anorexic, the impossible link to the mother and the dependence on the family have foreclosed an independent future and normal adolescent distancing. Anorexia is both an attempt at self-cure and a terrible vengeance in which the body destroys itself. The mother is the enemy that the anorexic can only defeat in a fight to the death. The body, object of maternal power, is slowly killed. From the unconscious hate toward her mother the adolescent girl draws her avowed repugnance toward food and the rejection of her own body. Everything persecutes her—her body, food, her parents, the outside world. The body, essential in the eyes of the mother, becomes the instrument of vengeance: abused, controlled, used with a view to annihilating itself. This body, in a mirror image of an unspeakable violence, reflects to the mother its destructive omnipotence: It’s yours now, it is nothing to me anymore; you can cry, I no longer live in it.

Nicolas de Staël, Les Mouettes, 1955

The father, if he finally arrives, shows up very late. He did not intervene. This wife—this effective, devoted, reassuring mother—always knew how to dry up tears, cook tasty meals, check up on homework, go to parent-teacher meetings—what could her child have lacked? The father did not regulate distance, as his function required; he did not make the symbolic cut between mother and child, two merged beings, so that between them there could be the space that ensures vitality.

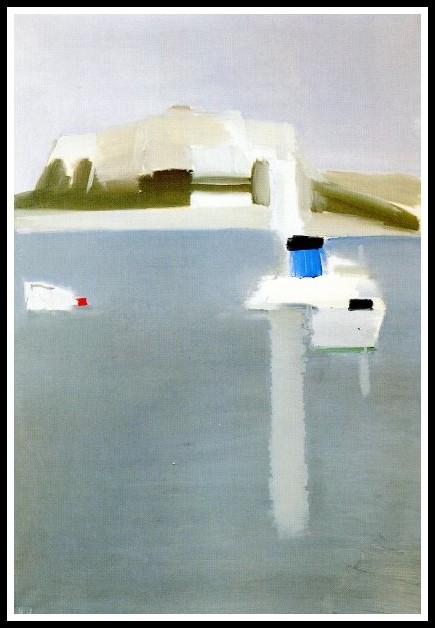

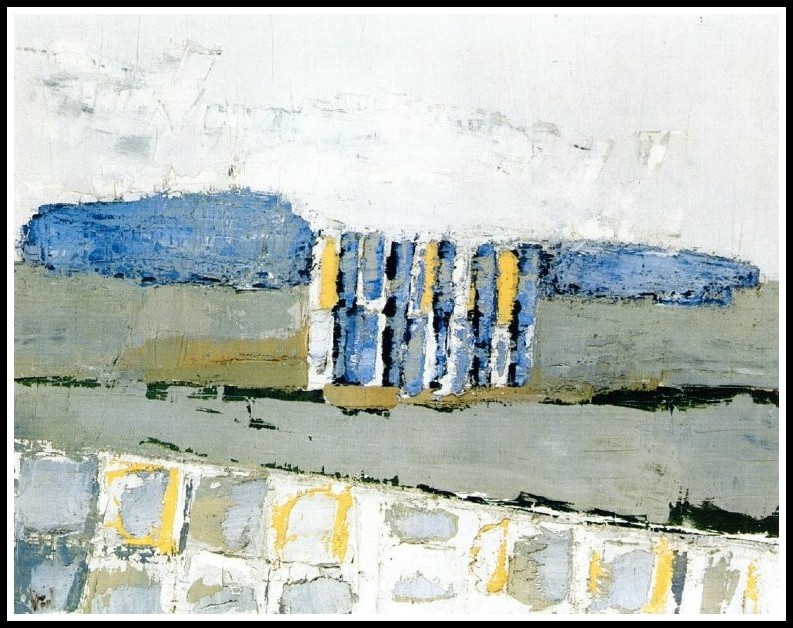

Nicolas de Staël, Le Fort d’Antibes, 1955

The parents do not understand that this girl to whom they have given everything has become resistant to their love. They were not aware that they have smothered the child with kindness. Between paralyzing love and terrifying distance, the food left on the plate and the thin body of the child materialize their anxiety. The girl, for her part, discovers the fascinating power she has over her parents. The symptom, from a simple call for help, becomes an entrenched ritual that no-one can undo anymore.

Nicolas de Staël, Le Fort-Carré d’Antibes, 1955

II. HOSPITALIZATION

Made essential by the state of the child’s body, hospitalization brings the institutional framework into play and leads to the family interviews that will reveal the impasse the relational dynamic is stuck in. The life-threatening crisis offers an opportunity for questioning. The girl, rather than remaining a captive of the other’s omnipotence, allows herself to be confined. Does this make a cure possible?

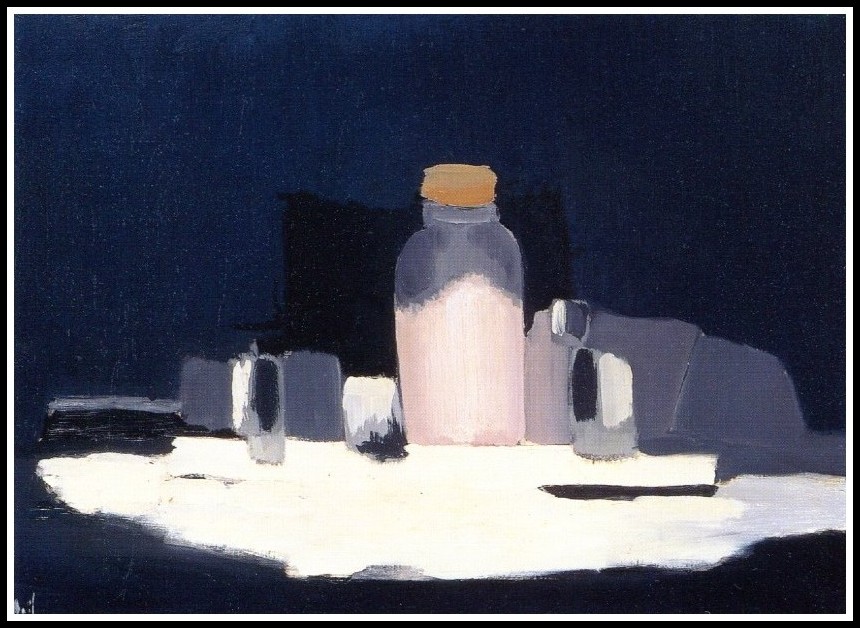

Nicolas de Staël, Le Bocal, 1955

At the hospital, the anorexic replays with the caregivers scenes from her family life, desperate manifestations of her omnipotence: she does not eat or pretends to do so, she vomits, she cheats whenever possible, she does not talk or talks too much, she makes herself unbearable.

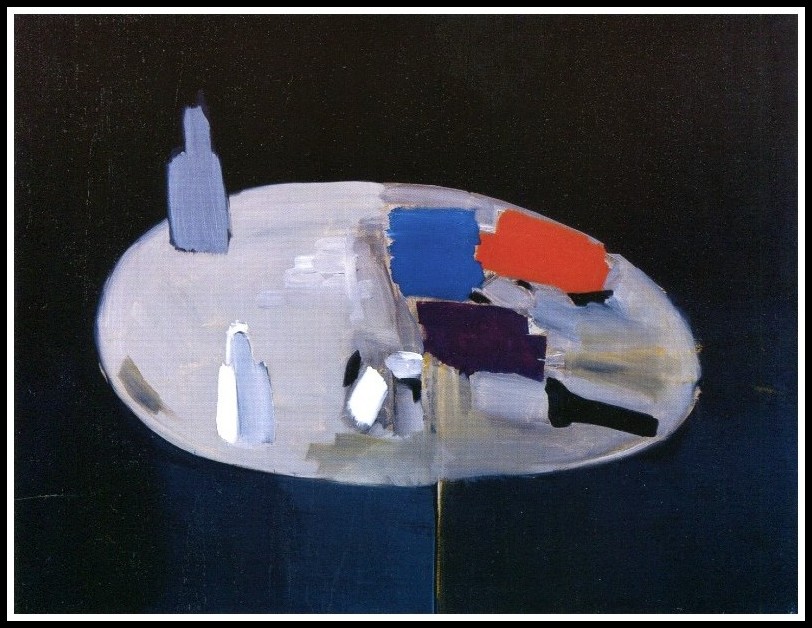

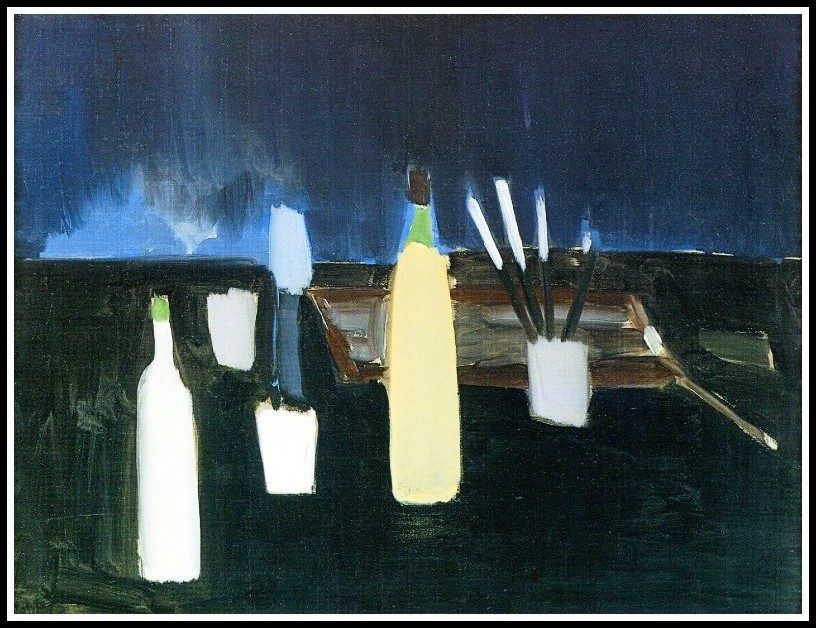

Nicolas de Staël, La Palette, 1954

In our pediatric ward, we do not use weight contracts (whereby a gain in weight is rewarded with a removal of restrictions and prohibitions); however, in the event of weight loss, force feeding is practiced. The pediatrician says: ‘What is important is your overall health; we will not let you die.’ This behaviorist approach—‘You can leave when you reach a given weight’—can indeed rapidly reduce the symptom. The patient will gain weight under duress. We know all too well, however, how much this victory of the therapist over the body of the patient is felt by her to be a betrayal, an alliance with the family: she has not been heard. Losing weight is only a pretext; the heart of the matter lies elsewhere. It is written on the body, but to be cured the anorexic must find the right words, write the narrative of her origins and speak.

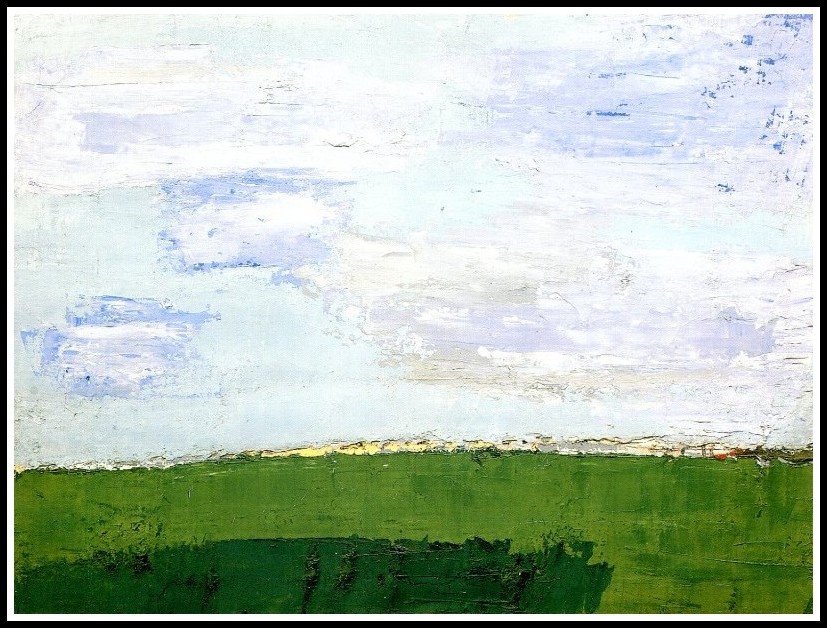

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage, 1952

III. ISOLATION

Our Western culture no longer offers the rituals, alive and widely-accepted in other societies, that mark the delicate passage from childhood to adulthood. A ritual organizes interpersonal relations; it accords everyone a place and redefines the nature of their relations. It suspends time and space. Among rites of passage, the rites of puberty address the end of childhood. Separation from the mother is the first event. For both mother and child, separation represents a death. The change underway opens out onto the unknown, which frightens the adolescent. A common element in all rites of passage is the solitary voyage: the child moves away from the mother and the community. The initiate is subjected to ordeals and is instructed by adults of the same sex as he/she from outside the family. The rite often involves passage through a dark place, compulsory fasting, and taboos on certain foods. It is a symbolic death, a return to the womb, and a promise of rebirth.

Nicolas de Staël, Mantes, 1952

During the hospitalization of the anorexic, isolation, by imposing separation, becomes a therapeutic family rite of passage. The whole triad of father, mother and daughter (and, in addition, any siblings) is confronted with an extreme experience: the brutal rupture of relations, solitude, the anxiety of death, powerlessness to help a loved one, the meeting with a stranger.

Nicolas de Staël, Orchestra, 1953 (detail)

In the contract signed with the anorexic’s family, isolation (of which there are different levels) entails that at a certain time communication between parents and patient will be forbidden: no visits, no phone calls, no letters. During this period, the caregivers provide the parents with any information they may want about the state of the child. I deliberately say ‘child’ in order to emphasize the extent to which the anorexic, be she young girl or woman, occupies an infantile place of dependence, whatever demands for independence she may articulate.

Nicolas de Staël, Orchestra, 1953 (detail)

The anorexic’s family always seeks an external cause of their daughter’s predicament: mixing with the wrong kind of people, understandable disgust toward food, disappointment in love, death of a beloved pet, etc. To consider the possibility that the origin of the disturbance may lie within the family is unthinkable. We observe that memories, events and projects are experienced and expressed via a myth of unity in which no member of the family speaks in his or her own name: ‘We thought…’, ‘We all agreed that…’, ‘She doesn’t realize…’. In the anorexic’s family, ‘I’ is a danger for oneself and others.

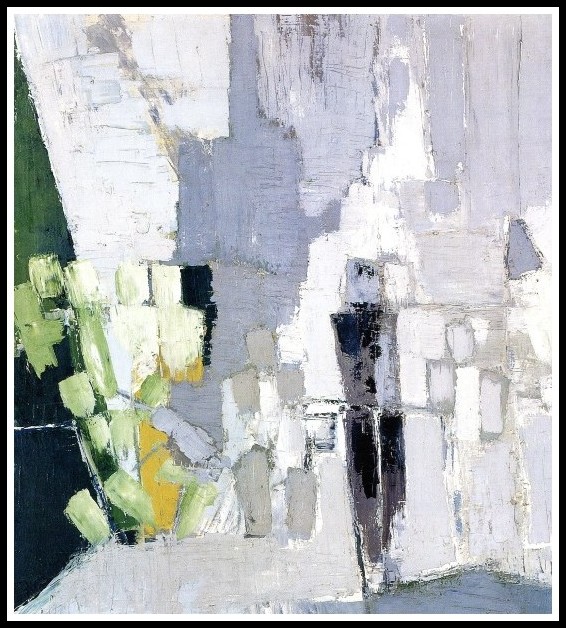

Nicolas de Staël, La Cathédrale, 1955

Isolation sets limits. The goal of prohibiting communication is to put an end to pathological interaction; the rupture will produce effects that we hope will stir to action. The following sequence is an illustration of pathological interaction:

– I eat what I want.

– You don’t eat enough, so I keep an eye on you.

– You keep an eye on me, and that gets on my nerves. (But your concern interests me, so to keep the game going, I don’t eat enough).

Isolation deprives the players of partners, and so puts an end to the game.

Nicolas de Staël, La Table de l’artiste, 1954

What our therapeutic protocol aims at, then, is to get out of the dead end of designating the parents ‘bad’ and the daughter ‘sick’ and ‘anorexic’. At the beginning of the hospital care program our approach is to consider the symptom a sign of a relational dysfunction the family cannot overcome. In these families where one must not talk too much, we can now discover the vulnerabilities and the pain that is kept secret, denied, and suffered in silence. At a later stage, we can suspend the family-therapy approach to address each individual’s particular issues.

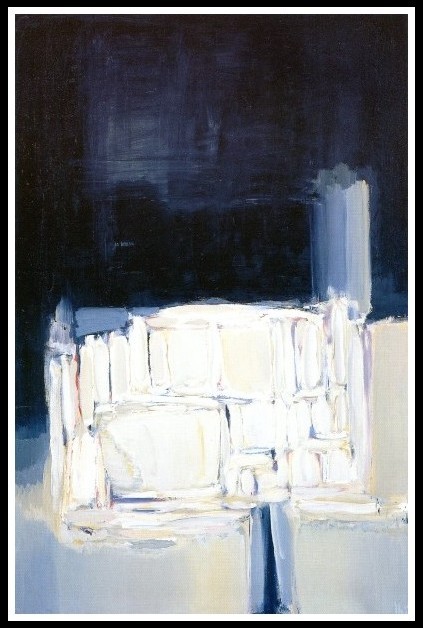

Nicolas de Staël, Mer et nuages, 1953

IV. Lydia

Lydia was hospitalized in our pediatric ward at age fifteen and a half. At first, the prohibition to communicate had the expected beneficial effects, but it quickly gave rise to a fear of death verbalized by the mother, but which we believe was felt by all. This fear went well beyond the usual fear parents have of seeing their daughter die of anorexia.

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage, 1952

Lydia was conceived three months after the crib death of her four-month-old brother. In line with then-current thinking, the second child’s sleep was constantly monitored. In this technical set-up, the mission of the parents was to put the baby on life support in case of serious cardiac slowdown. For Lydia and her parents, the rhythm of her heartbeat, anxious silences and false alarms characterized her first few months of life. Rather than a joyfully welcomed baby daughter, Lydia was a body to be kept alive.

Nicolas de Staël, Ciel à Honfleur, 1952

A second daughter was born three years later, then much later a son. Lydia became anorexic at age fourteen, soon after the birth of that brother. The model girl, excellent student, and contributing homemaker, had done all she could to be loved; now, with this birth of a boy, she no longer knew who she was.

Nicolas de Staël, Le Parc de Sceaux, 1952

Psychoanalysis has taught us that the replacement child occupies the position of substitute, with no existence in their own right. In the parental unconscious, the dead child merges with the living, one is taken for the other. The substitute child tries to identify with the one whose place she occupies, the one ever-present to her parents, while her suicidal behaviour tests her parents’ desire: Do you want me dead or alive?

Nicolas de Staël, Les Mûriers, 1953

Anorexic, Lydia has the silhouette of a boy—no breasts, no buttocks, no hips—and no periods. Her hyperactivity gives her an existence among the living, but her skin-and-bone appearance attests to her attraction for the kingdom of the dead where her predecessor ‘lives’. By the very fact of her survival, she silently interrogates her parents: ‘Who is dead?’, ‘Who is alive?’, ‘Have you made me a place of my own among you?’, ‘What do you desire for me?’.

Nicolas de Staël, Les Cyprès, 1953

In this family that has not mourned the first son, the children do not know what has become of the corpse: Was there a funeral? An autopsy? Was he buried or cremated? Where is he? The two daughters did not dare to ask their questions out loud. The younger one searched everywhere, and finally discovered the urn with the ashes in the father’s night table. That was six years earlier, in grade one, a time when children’s eagerness to learn is applauded. She quickly put the lid back on and kept quiet about her discovery until our interviews (at which all the children, at my request, were present). Lydia, for her part, stopped eating in order to live: ‘What’s the point of living if you don’t know who you are?’, ‘What’s the point of eating if you never have time to be hungry because your mother is always feeding you to keep you alive?’, ‘Who am I, besides this mouth to feed?’. ‘For them, I eat therefore I am, and that’s all’.

Nicolas de Staël, Grignan, 1953

V. WHAT HAPPENS DURING ISOLATION?

In the beginning, despite her complaints, Lydia is content in her isolation: ‘I was fed up with their visits; we had nothing to say to each other’. She is left to face her fantasy: she is lost, disappeared, almost dead to her parents. Without their gaze upon her, however, she is afraid of being lost to herself. She wants to remain alive to see what they will do, what they will say: ‘Will they continue to care only about my eating, my weight, my body—my body which is such a burden to me—or will they finally talk of what is important?’ For her parents, isolation is a disruptive force that throws into relief their original fear, the fear of finding Lydia dead in her crib. The anxiety is ever-present. Shortly before the hospitalization, the mother said to the daughter: ‘I won’t be able to prevent you from killing yourself’.

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage au nuage, 1953

In this family where silence signifies death and absence fatality, we proposed that writing serve as a means to connect the family members to each other. But what kind of writing? Writing as a path to the symbolic, writing that creates meaning there where speech is absent or words mere decoys; writing that keeps isolation from doing violence, contrasting with the anorexic’s omnipotence and the parents’ fear of her death; writing that restores flow to time and focuses attention on the present.

Nicolas de Staël, Face au Havre, 1952

Up to this point letter-writing had been forbidden. We then told parents and daughter that they needed to write to each other. Concretely, we told them to mail their letters rather than to convey them via the clothing bag; we told Lydia to write to her mother and father separately, and we told the parents to write independently, without discussion with each other beforehand. The parents, utterly dismayed, did not know how to respond to the flood of letters they received, letters that were searching, aggressive and ruthless, the inexhaustible vomit of a child nourished all too well. To their daughter who had finally dared to express her anger, the parents, each facing themself alone, had to respond. Dialogue was established. ‘I’m preparing my mother for what I will tell her when I see her’, Lydia told us. In her letters she asked her mother, ‘Who am I for you?’, ‘Why did you make me?’, and her father, ‘Where is he buried?’, ‘Why is it that in our house, mummy is the man?’.

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage, 1953

It was during the first family meeting after this intense period of letter-writing that true words were spoken in the presence of everyone. The younger daughter brought up her search for the missing body. The mother made an admission to Lydia: ‘If he were alive, perhaps you wouldn’t be here’. The father, given to conflict-avoidance and self-effacement, was finally able to stop hiding behind his wife and speak in his own right.

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage, 1952

In the solitude of writing, the imposed separation was no longer experienced as a place of deathly emptiness but had become a productive period, a symbolic act that fostered the creation of an identity for each family member. For Lydia, after this interval of regression in the womb of the hospital and the discovery of hate in both herself and her parents, she began to consider on what grounds she could construct her future, asking herself, ‘Who am I? Their daughter, yes, but no longer a child—who am I?’.

Nicolas de Staël, Grignan, 1953

Lydia’s mother called her daughter ‘Snow’. Knowing neither how nor why to live, Lydia was in suspension, dormant. Underneath the snow, we recall, dormant life awaits its moment of awakening.

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage, 1952