VALÉRIE VALÈRE & ANOREXIA

A Post in Three Parts

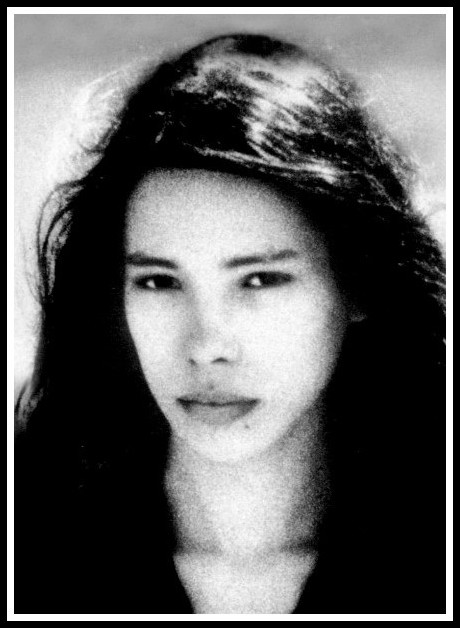

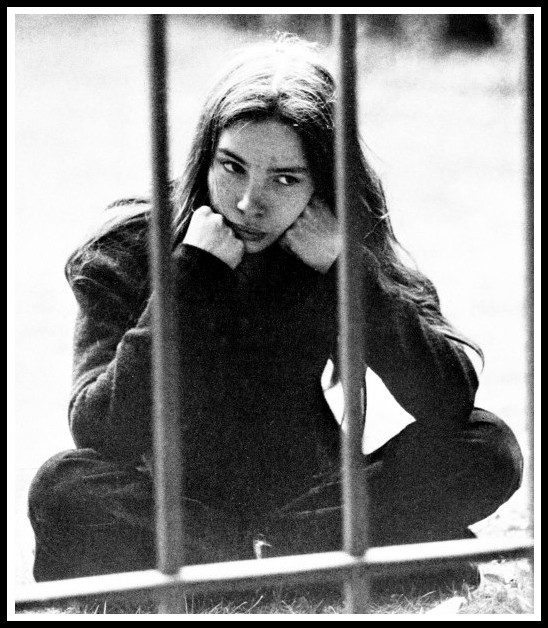

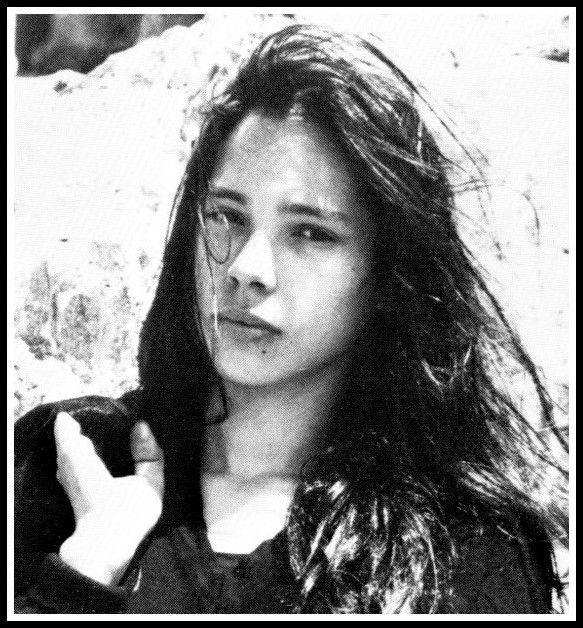

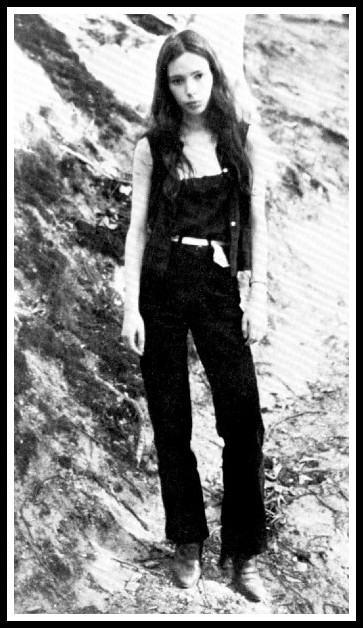

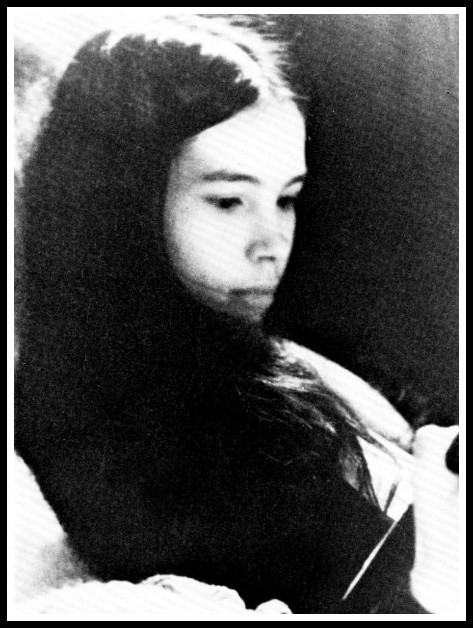

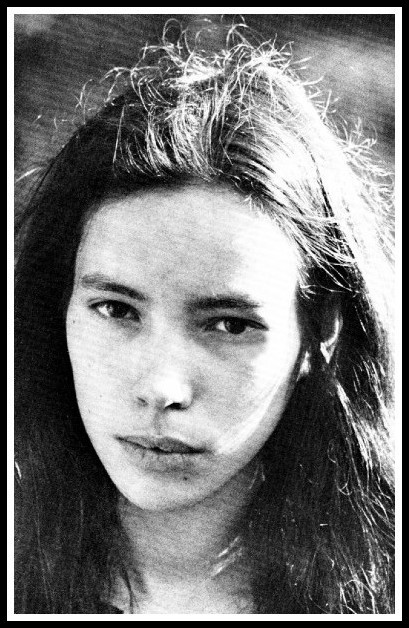

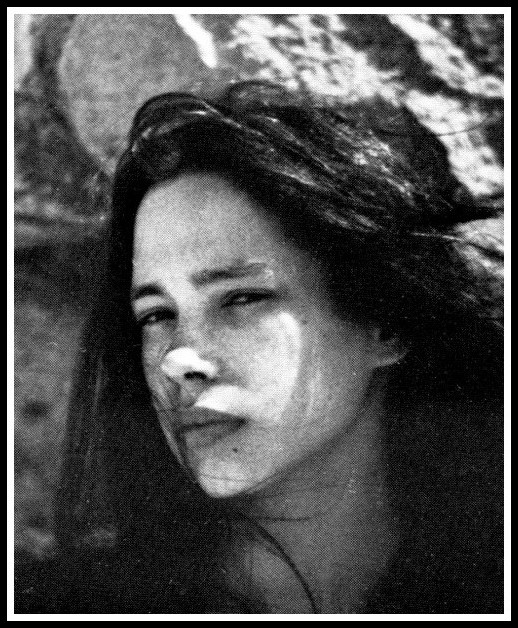

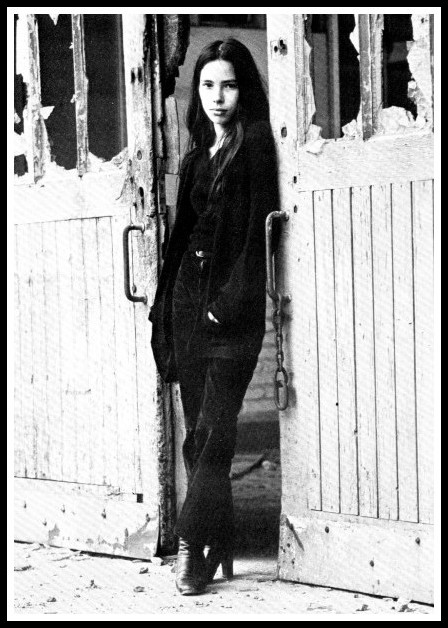

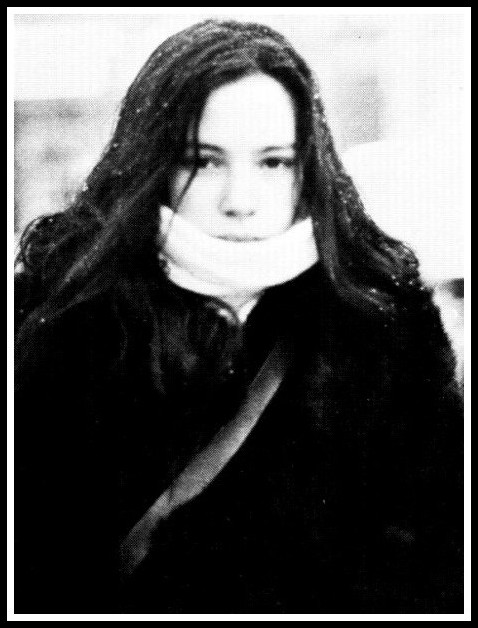

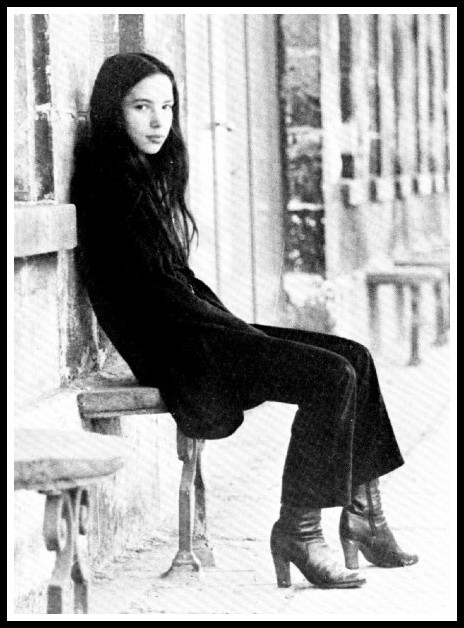

VALÉRIE VALÈRE, 1 NOV 1961 – 18 DEC 1982

Photo: Guy Lenoir

PART I

HOMAGE TO VALÉRIE VALÈRE

Richard Jonathan

PRELIMINARY NOTE TO VISITORS FROM OUTSIDE FRANCE

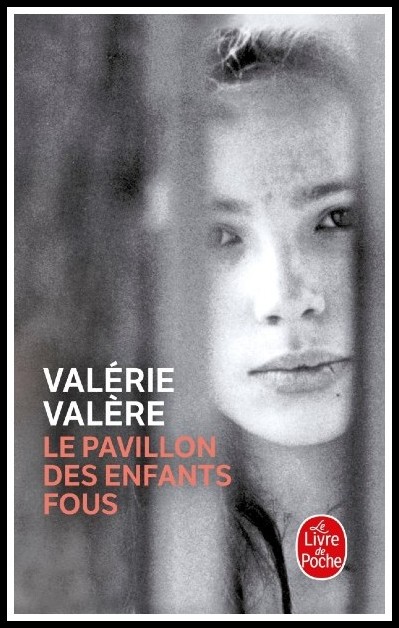

In 1976, aged fifteen, Valérie Valère wrote Le pavillon des enfants fous, a scream of protest against her confinement for anorexia in the ‘mad children’s ward’ of a Parisian psychiatric hospital in 1974, when she was thirteen. She was locked up for four months until, having gained the requisite 10 kilograms, she was freed. Recurring like a refrain throughout the work, ‘They won’t get me!’ is Valérie Valère’s defiant battle cry, hurled against all who would reform her. The book was critically well-received and sold well upon its publication in 1978; daring the reader to be indifferent, for a while it marked the French reading public.

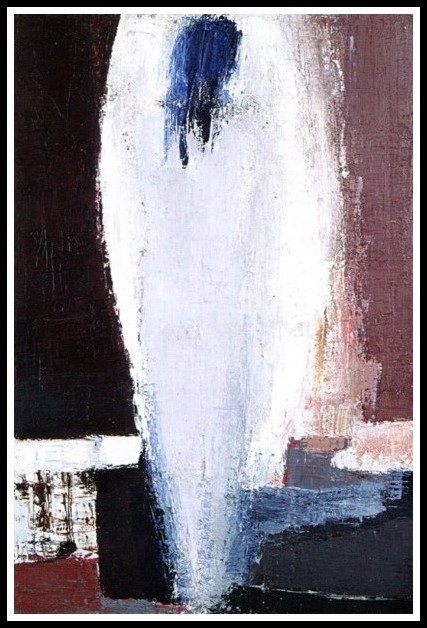

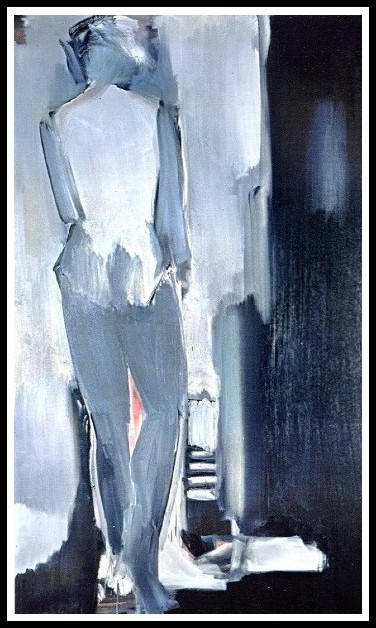

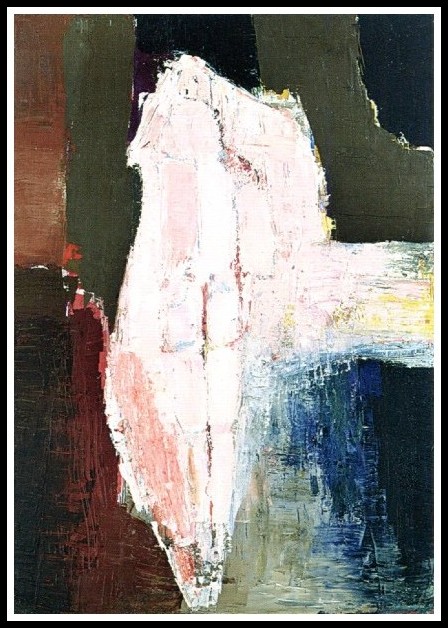

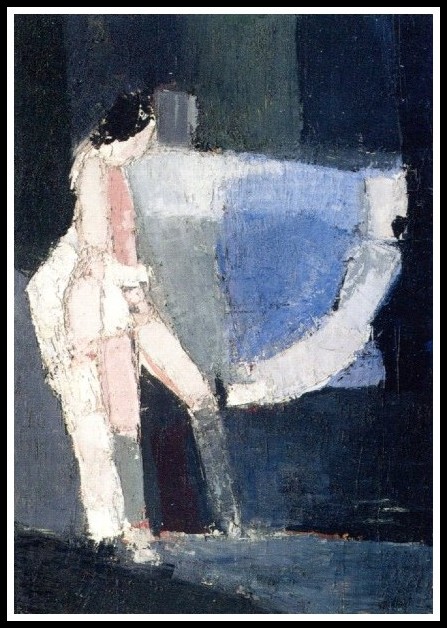

Nicolas de Staël, Nu debout, 1953

Today, while her book continues to sell steadily, Valérie Valère is not a name with wide resonance in France. Even in the community of clinicians she receives barely a passing mention. Not surprising, then, that outside France her name means nothing. Indeed, while the translations of Le pavillon des enfants fous into Spanish (Diario de una Anoréxica) and German (Das Haus der verrückten Kinder: Ein Bericht) are now out of print, the book was never even translated into English. I find it hard to accept that Valérie Valère is so unknown, because for me she is an exemplary figure. This post, then, aims to shine a light on why her life is worth remembering.

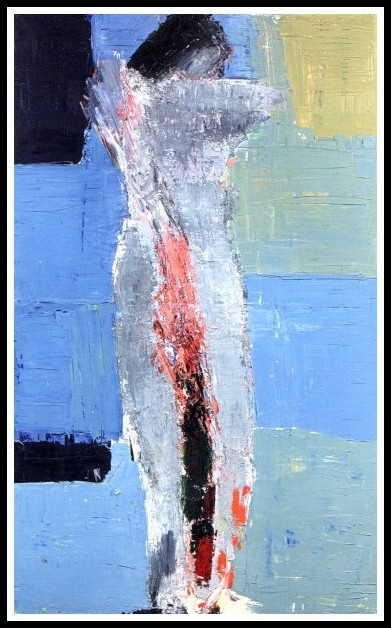

Nicolas de Staël, Nu gris de dos, 1954-55

Had Valérie Valère been born in London instead of Paris, her life might have been saved by rock ’n roll. Had Rimbaud been on her Sorbonne program instead of Victor Hugo, she might have experienced a more productive derangement of the senses. Had she been in dialogue with R.D. Laing instead of under interrogation by a two-bit psychiatrist, she might have kicked off her shoes and gone dancing. As it turned out, desperate for what her deadbeat father and not good-enough mother simply couldn’t give her, she renounced the struggle and pilled her starved body to death. In so doing she procured, along with the nothingness she so desired, her immortality.

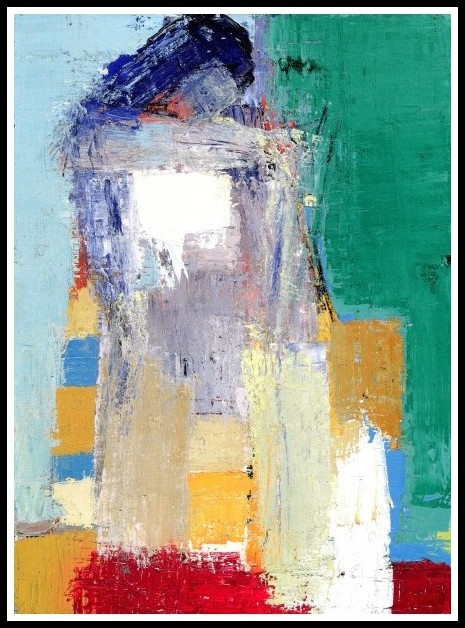

Nicolas de Staël, Nu assis, 1954-55 (detail)

Indeed, Le pavillon des enfants fous, her cry from her season in hell, is irreducible to any discourse, be it psychoanalytic, sociological or existential: It is first and foremost a voice, the voice of a fifteen-year-old girl safeguarding her soul from violation. Yes, Valérie Valère is in the grip of a set of dynamics she cannot understand; yes, she cannot cross the threshold of the open door she is banging on, but no, discursive language cannot negate the silence in her voice, the silence from where she speaks: the sidereal silence of the isolated individual. For having borne witness to that state, Valérie Valère, for as long as silence has a place in the busy world, will be immortal.

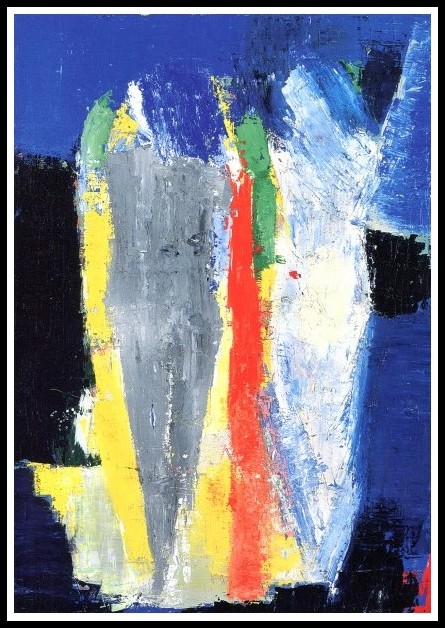

Nicolas de Staël, Les Indes galantes, 1953

Why didn’t she wise up? one may ask. Why did she move back in with her mother when, despite the smoldering cigarette that set her room aflame, she could have continued to live on her own? ‘Wisdom is cold’, as Wittgenstein said (Culture and Value, 53e), ‘you can no more use it for setting your life to rights than you can forge iron when it is cold.’ Valérie Valère never found the heat that could have melted the chains that tied her to her mother; she never found the fire that might have dissolved her fixations.

Nicolas de Staël, Les Indes galantes, 1953

If not rock ’n roll, if not poetry, if not kindness and intelligence (all akin to fecundating fire), what might have enabled Valérie Valère to ‘become who she is’? What might have enabled her to fulfill Nietzsche’s dictum? Laughter. Yes, to avoid being consumed by her hunger for nothing (Lacan, see below), by her petrifying obsessions (Dolto, see below), and to become who she is, she needed an aesthetic model of the self that laughter might have procured her.

Nicolas de Staël, Nu debout, 1953

Yes, loosened by laughter, she might have pursued fatalistic self-creation instead of fatalistic self-destruction; she might, unbeknownst to herself, have echoed the example of Nietzsche’s life. So yes, Valérie Valère needed laughter; laughter as in the slapstick of Waiting for Godot, the grotesque of Watt, the finger given to fate in the mirlitonade that goes, En face le pire, jusqu’à ce qu’il fasse rire: Ahead, the worst, until laughter makes you burst. (All works by Samuel Beckett; the translation of the mirlitonade is mine.)

Nicolas de Staël, Nu couché, 1953

The worms got slim pickings off Valérie Valère’s bones (or, as she was cremated, let’s say her sterile ashes made no difference to the living sea), but Le pavillon des enfants fous is rich soul food. No encounter with rock ’n roll, Rimbaud or R.D. Laing occurred with her; with laughter, too, she missed the rendezvous. If we did not live in a post-tragic world, those missed rendezvous would, as I see it, be the tragedy of Valérie Valère’s life. But, since we do live in a post-tragic world, I, for my part, will do what I can to honor her: I will echo the silence in her voice, I will shelter the flame of individuality.

Nicolas de Staël, Figure debout, 1953

Why? Because I admire people who, to safeguard their soul, adamantly say No. Like Melville’s scrivener, Bartleby; like that Palestinian fanatic, Jesus; like that French thief, Genet, I too say No; like that Czech insurance clerk, Kafka; like that English rock ’n roller, Peter Perrett; like that American poet, Patti Smith, I too say No. Yes, as hyper-consumerism gets ever more invasive, saying No to affirm one’s individuality is ever more necessary.

Nicolas de Staël, Figures, 1953

Valérie Valère said No in a voice rich with silence; may her example serve to make silence speak in the noisy world.

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

PART II

VALÉRIE VALÈRE & ANOREXIA: A LACANIAN INTERPRETATION

Valérie Pera-Guillot

Valérie Pera-Guillot, psychiatrist, hospital practitioner & psychoanalyst, is a member of the École de la Cause freudienne.

From Valérie Pera-Guillot, ‘L’anorexie: de la solution au symptôme. Pas sans angoisse.’ Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

In Le pavillon des enfants fous, a book that reverberates like a scream, the author, Valérie Valère, retraces the experience of her four-month internment in a psychiatric hospital for children. At age thirteen, extremely thin after having refused to eat for weeks, she was hospitalized there. If certain aspects of the book echo the antipsychiatry of the 1970s, in no way can it be reduced to it. Driven by a sense of urgency, Valérie Valère wrote it a few months after her discharge from the hospital in 1976, when she was fifteen years old.

Valérie Valère, Le Pavillon des Enfants Fous, 1978

In it, she gives an account of an intense solitude, that of an anorexic subject locked in a self-destructive autistic jouissance that fuels her refusal of an intrusive Other who penetrates her body and her thoughts on the pretext of knowing what is good for her. Anorexia as a refusal of the Other is absolute here, being the only means this young subject has found to ward off the threat of submission to the omnipotent, malicious Other. The Other is not only the mother, but also the doctors, the caregivers, the psychologists and psychoanalysts that she meets.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

The tone is set right from the evocation of her arrival at the hospital in the opening pages of the book: No, I will not give in to their humiliating blackmail; the thought never even crossed my mind. They won’t get me, that’s all I know how to say now. They dragged me by the hair into this fortress: ‘You’re sick, we’ll take care of you here; you’ll see, you’ll get better.’ No! I’m not sick, I feel very well. You can keep your damned care, I want to remain alone with myself, I won’t go with you! They stared at me with empty eyes, their hands ready to grab me. I don’t need anybody, I don’t give a damn for all these people, I reject them! What does it matter anyway? The only sources of support were the other anorexic or bulimic girls that she came across in the ward, girls with whom she tried to establish a dialogue that the institution, however, did not allow.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

Alongside this refusal of an Other who would gain jouissance through her, there is the impossibility of the subject to inscribe her changing body in her own story; furthermore, for lack of a possible handling of semblances, there is also an impossibility of coping with the real: It annoys me to speak of my childhood. No, I accept without really believing, that it might have been more important than ‘adolescence’. And yet how things then appear to you outrageous in their derision, humiliating in their immodesty, loathsome in their uselessness. You have the impression of being nothing but a horrible brat who spends her time walking the streets without even knowing where she is going. Everything is more intense, everything takes on a second meaning over that of childhood, a meaning so disappointing, so useless.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

Valérie Valère, through writing, will attempt to inscribe this experience in a story: Those four months remained so present in me, so much that I understood that if I did not give an account of my time spent in the mad children’s ward it would do me harm, would stand between me and life. I had to find a way out.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

Despite several novels and a certain success that gave her a place in the Other of the literary world, Valérie Valère would remain addicted to nothing, that nothing that had led her to be hospitalized in a state of cachexia at age thirteen. At twenty-one, after several suicide attempts, she died alone, having taken an overdose of tranquilizers and sleeping pills that, finally, proved fatal.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

PART III

VALÉRIE VALÈRE & ANOREXIA: A FREUDIAN INTERPRETATION

Françoise Dolto

Françoise Dolto, together with Jacques Lacan, founded the ‘French interpretation’ of Freud. From ‘Anorexiques et Timides’ in Françoise Dolto, Solitude (Folio essais, 1994) pp. 284-86.

Translated here by Richard Jonathan. Note that the text is a transcription of an interview, hence the conversational tone. It dates from the late 1970s-early 1980s.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

I read Valérie Valère’s book, Le pavillon des enfants fous. Primary and basic. No distance. We see someone who has never been analyzed and who has it in for Daddy and Mommy. It’s her self-construction during the oral-anal phase. What she said against her mother was pretty vicious. There was a conscious refusal to identify with that mother but, in reality, she identified with her much more profoundly than an adolescent girl who’d grown up normally would have done. She never got beyond her Oedipus complex. What she really wanted was to have her parents argue over her.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

It certainly did Valérie Valère good to write the book. She was in hospital to write. (It’s a little like Fritz Zorn who wrote Mars and who died of cancer.) She really piles fantasy upon fantasy. The reader can believe the author has horrible parents, whereas they have the same neurosis as she does, only with different effects, fusional in the case of the son. It’s another aspect of the same unconscious libidinal dynamic as her parents—it’s mimicry. It’s a family neurosis in which the subject is trapped in a fusional ego with the asexual ego of the two parents. It hurts me to see people remain like that, at such an elementary level of behavior, struggling to separate themselves from each other and, because they are so fusional, not managing to do so. They’re like flies stuck on fly paper—the more they struggle, the more stuck they become.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

Whereas in the case of Valérie Valère it is by an interpretation of her mother’s suffering at the hands of her own mother, the maternal grandmother transferred onto her husband, Valérie Valère’s father, that she could have freed herself from the consequences of her homosexual, Oedipal early childhood expressed in her anorexia, her oral fixation. Why, born of that particular mother, did she take pleasure in her infantile relation? She had trapped herself, when she was a little girl, in the love of her mother, a mother who remained a child. She was trying to extricate herself from her tenacious desire for incest by weaning herself of food, as if to eat were to remain at the breast of this child-mother.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

Thanks to Le pavillon des enfants fous, a book whereby she vomited on her parents, she was able to earn enough money to free herself from her economic dependence on them. I’m not at all surprised that she committed suicide. Her unconscious guilt was much too great : she wrote the book alone in her room, but once it was published and her parents came across as appalling people, she could no longer live, since she had been shaped by them. It was as if she was shaped by shit. At puberty, on must die to one’s childhood, but it is imperative that the fundamentals of what was shaped in childhood remain the foundation of adolescence.

Valérie Valère | Photo: Guy Lenoir

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2021 | All rights reserved

Comments