HOMAGE TO ANNE DUFOURMANTELLE

Richard Jonathan

The high one expects from sex is generally not intellectual, yet an intellectual high is precisely what Anne Dufourmantelle provides in her brilliant book, Blind Date: Sex and Philosophy.

Anne Dufourmantelle – Blind Date

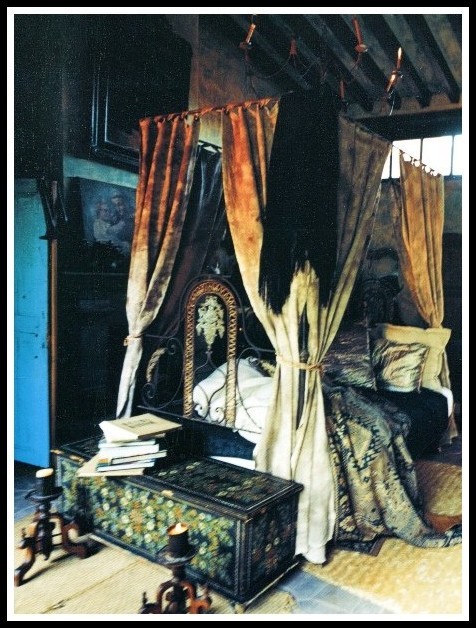

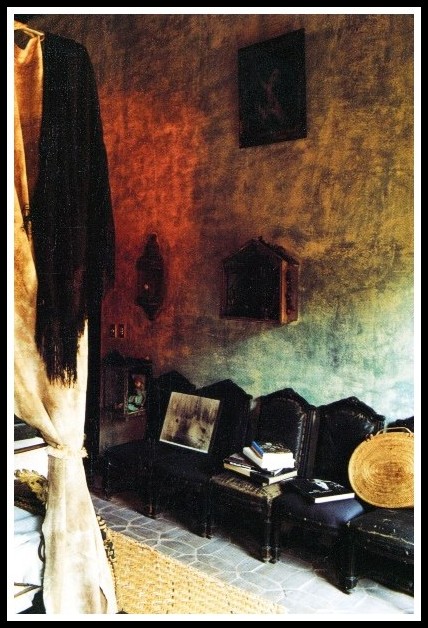

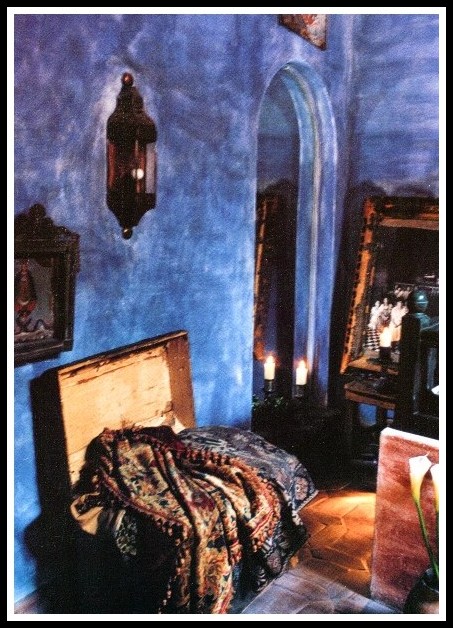

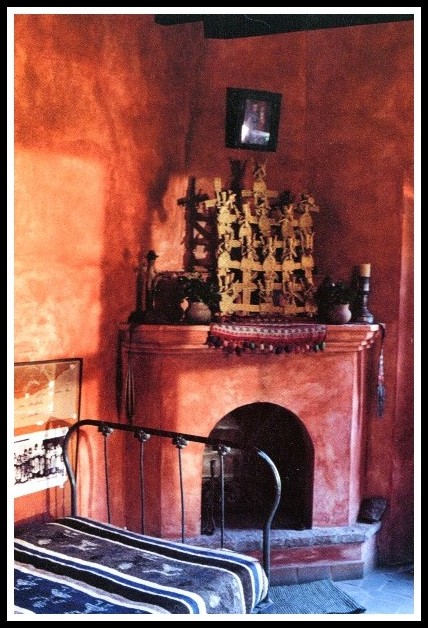

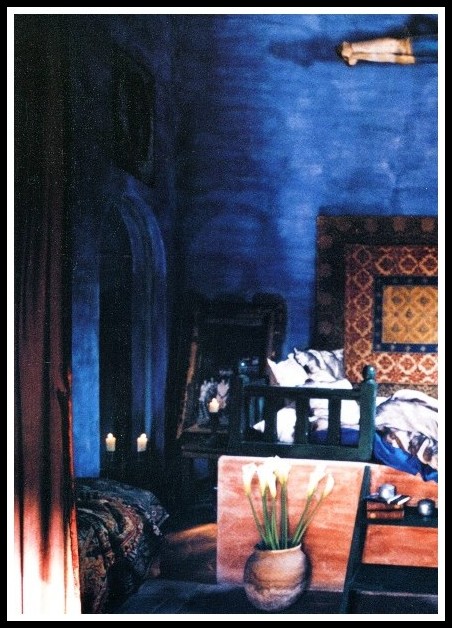

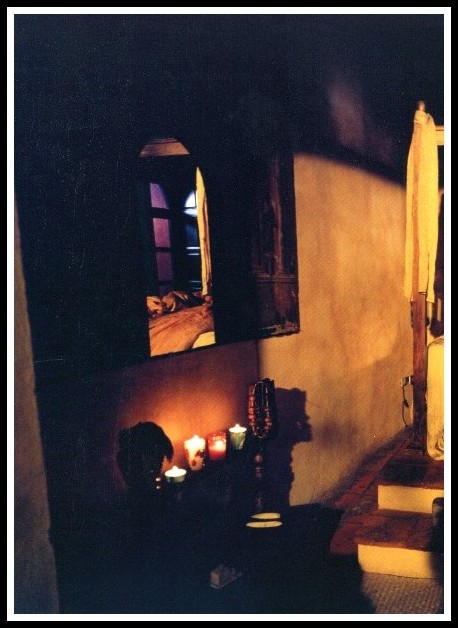

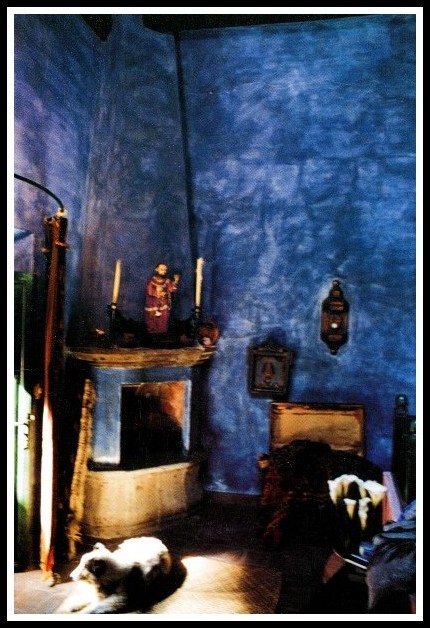

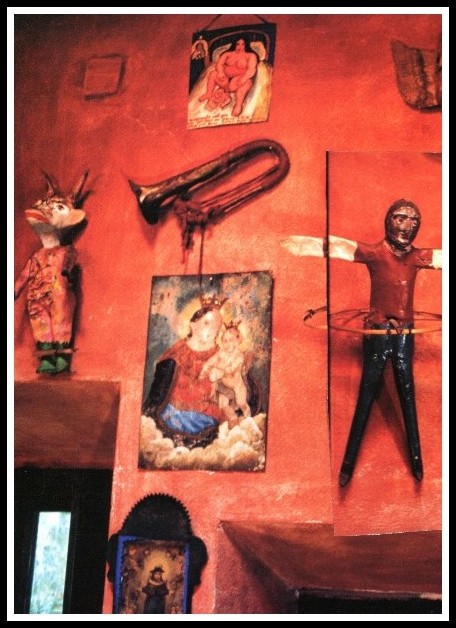

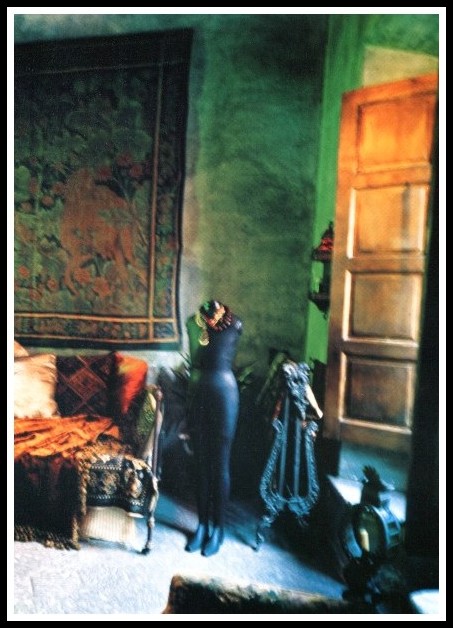

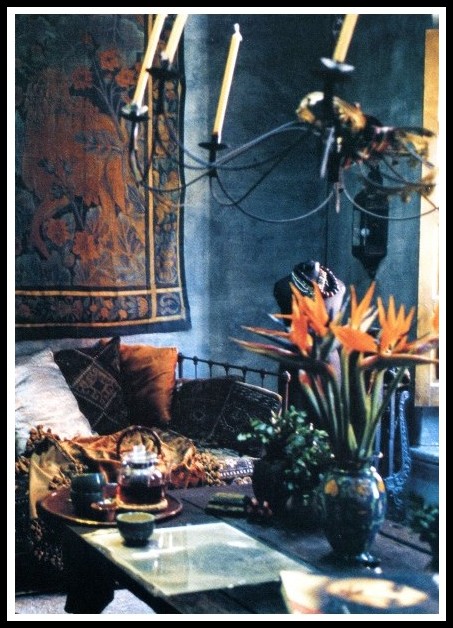

Philosopher, psychoanalyst, novelist, Anne Dufourmantelle left behind a body of work abounding in stimulating ideas when, on 21 July 2017, at age 53, she died while attempting to rescue a child drowning in the sea at Pampelonne, a beach in the South of France. This post, an extract from Blind Date that I have complemented with photographs from Deborah Turbeville’s Casa No Name, is my tiny contribution to honoring her memory. It is also a token of my gratitude for the multiple hours of intellectual high her work has procured me. Elisabeth Roudinesco’s obituary* highlights a dimension of Anne’s work that has been instrumental in my own development, namely her articulation of an ‘aesthetics of living’: ‘To take the risk of loving, to eradicate dependence in the way one lives, constitutes the ground of all ethics’. Roudinesco then goes on to remind us that, in her 2011 book, In Praise of Risk, Dufourmantelle drew out of a line from Hölderlin—‘where danger is, grows the saving power also’—the proposition that ‘daring to risk could be the miraculous opposite of neurosis’. In honor of Anne Dufourmantelle, then, in honor of her aesthetics of living, I offer this post in the hope that it will prompt you to explore her work more widely.

* Le Monde, 24 July 2017 . Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Anne Dufourmantelle | Photo: Roberto Frankenberg

BLIND DATE: SEX AND PHILOSOPHY

Anne Dufourmantelle

From Anne Dufourmantelle, Blind Date: Sex and Philosophy, tr. Catherine Porter (University of Illinois Press, 2007) pages 1-7

Anne Dufourmantelle | Photo: Reporters/Leemage

INTRODUCTION

BLIND DATE is the term for a meeting between two beings who do not know each other, who may be able to love each other—a meeting organized by someone else who knows them both and who will not be present at the encounter.

PHILOSOPHY begins with astonishment (Aristotle), declares itself the science of being, hopes to provide for the soul, finds its etymology in love of wisdom, imagines spiritual education as its vocation, rights itself into a logic of propositions, lingers in schoolbooks, is written in all languages but is thought to think in just one, is quietly dying out.

SEX ends when explanations are required, comments on itself only as it disappears, disrupts any script that seeks to isolate its effects, is present everywhere, all the time, is absent everywhere, all the time.

The meeting was scheduled, they say, three thousand years ago. Officially, at least. Since then, it has been continuously postponed.

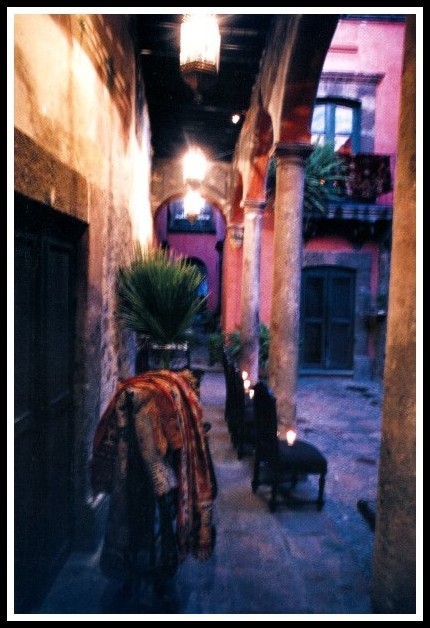

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

RENDEZ-VOUS

From the start, there is astonishment. And hunger. To think, to devour. To be astonished (that the world exists). To be hungry (for the other). Aporias, cannibalism, eroticism, stories. Blind date: an encounter between strangers. Neither protagonist knows the identity of the other. The meeting has been arranged for them. The moment, the occasion, the place will do the rest. Who imagined the meeting? Who benefits from its staging? What agent is behind this encounter? No one, of course, neither a witness nor a third party who might be questioned, since here only disciplines appear. Sex, philosophy, and their more or less legitimate declensions: metaphysics, the biology of passion, rhetoric, logic, the mechanics of desire, ontology, the chemistry of the attraction between bodies, spiritual exercises, the physics of bodies, the phenomenology of perception, epistemology, eros, logos. The witness, then, will be impossible to identify; his or her motivation will not be understood. The witness will be said to be time itself, or else it will be said that the organizing principle of the blind date in place for three thousand years is the result of what is nebulously called ‘technology,’ at the point where science competes with life to invent intelligence, since no aspect of what fascinates us today is foreign to the bios, to the fabrication of life forms.

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

Sex and philosophy have been deliberately avoiding each other forever, who knows why; perhaps because they are of the same nature? Both seek the realization of an essence, that of desire or that of contemplation; both are treated as dangerous when in use—inflammable, corrupting, and socially subversive. Both are deflected toward multiple ends—consumption, sales, exchanges, power—that they both constantly elude. And what if sex and philosophy had always interacted by way of blind dates? No need for a friend to arrange a meeting, nor for a witness to watch its unfolding. The event will take place, has taken place, here, now, tomorrow.

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

PRELIMINARIES

How can one philosophize with sex? How can one sexualize philosophy? A blind date is pointless unless it allows the two separate protagonists to linger, with time for each to note the rough spots dotting a terrain on which there are no signposts. Because there is nothing out of the ordinary about the meeting place, it hardly lends itself to clandestine love affairs, nor does it invite solitary contemplation. Neither a Heideggerian Black Forest nor a rugged Nietzschean Sils Maria nor a Socratic banquet hall, it is a landscape open to the horizon, nothing more. With a sky for height and water for movement, the rest is a matter of the moment.

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

To philosophize about sex is to think of its philosophical preliminaries, its margins, its surroundings, its subterranean periphery, its steep slopes, its white lines. What makes it possible for us to think sex? What is required a priori? How does sex allow itself to be thought? Or rather, no, sex does not allow itself to be thought. One cannot start from two bodies, or several, that give each other orgasmic pleasure, jouissance, in order to construct sex as a concept. The image of sex intervenes. A privilege of conceptual installations that rely on forms to ‘display’ sex while keeping its truths out of sight. And in so doing expose it nonetheless. A vast mirror of images, field against field. Pornography, screens, overexposed sex—about which we still understand nothing at all, can say almost nothing at all, because sex is presumed to be a pure event that takes place, nothing more.

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

How has philosophy conceptualized sex? How has it approached the question a priori? That mingling of bodies, that desire, that hunger? Heraclitus conceptualized combat. Plato, the combat in the soul between the desire for pleasure and the desire for truth. Aristotle, the dynamics of a body moved by passion. Lucretius, the atomization of bodies. Plotinus, lost unity. Epicurus, dependence on pleasure. The cynics liked to be provocative. Augustine conceptualized the path leading out of the sexual wilderness; Giordano Bruno did the same. Nietzsche sought to demystify the power of reason over the body; Schopenhauer was the first to conceptualize the destiny of the drives. All of them forged a morality; none of them spoke about their own sexual lives. But what philosophy has carefully avoided conceptualizing is what could confound it, namely, desire, inasmuch as desire governs thought and sex alike. Not until the dawn of the eighteenth century did philosophy conceptualize itself as an act or an event outside the sphere of contemplation. It expended too much energy trying to compete with science for the right to produce objective knowledge of the world, trying to comprehend the laws that govern the world, trying to determine what animates the human soul, how the soul moves the body, what makes any body move, how evil can exist and be understood, how death already dwells in life from the start, and how the mind, alone, in exile, never stops contemplating these matters.

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

TWO OR THREE THINGS WE KNOW ABOUT THEM

One day, it begins. And one suddenly wonders why philosophy never speaks of sex and yet speaks of nothing else. Why don’t we think about sex when we read Plato, Kant, Heidegger, Pascal, Malebranche, Avicenna? Why should sex have to remain ignorant of philosophy, which in Greek, as everyone knows, means ‘love of wisdom,’ since nothing to do with love is foreign to sex? What is this sort of universal obsession—sex—that is supposed to disappear when we approach the forbidding walls of philosophical discourse? Into what other thing is it supposed to be converted: into pure love of thought? How and why could it be nowhere, or almost, in philosophical language?

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

He who has thought the most deeply loves the most spiritedly, Hölderlin tells us. For obsessions are peculiar in that they can change, can even change their object, but they cannot disappear, precisely because they are conflated with the subject. You obsess me to the extent that I become ‘you,’ I incorporate you, I believe you to be closer to me than I am to myself. If sex is an obsession—a quality that it shares, in a way, with philosophy—this is so in that it does not let go of us, ever. Even when we are not thinking about it, not engaging in it, even when we are sleeping, praying, laughing. Sex is the subterranean fiction that makes us beings pledged to ‘the other,’ without fail. Philosophy, for its part, is a derivative, secondary obsession. Because philosophy requires that the world be a source of astonishment for us, a source of anxiety and pardon. Thus that there be otherness.

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

To wonder, yes, why sex runs through everything, including the most resistant concepts, those that form the armature of metaphysics, like so many little metallic ribs: Time, Truth, Measure, Politics, Appetite, Being, Infinity, Face, Causality, Monad… All these are foreign to the question of sex, but none emerges unaffected from a confrontation with desire. Sex corrodes everything, including the abstract words that define the attributes of substance, mathematical figures, complex syllogisms. And yet… Because we read a philosophical text while forgetting ourselves as subjects of desire, sex must never be mentioned in it. Because we read the pages of a Socratic dialogue the way one ventures off into the distance toward an unknown territory that has been wiped clean of all the old landmarks, we prefer to forget that one enters into words with one’s body. Because we read a treatise on logic the way we would climb a wall barehanded, we expect from the hitherto obscure text a sudden revelation—reading as cannibalism, Nietzsche used to say, or thought as the art of eating raw meat—and the memory of a lasting astonishment. The wise man will reach greater depths by struggling to understand the paradox as such and will not try to explain the paradox by understanding that it does not exist, Kierkegaard suggests ironically. And what if the paradox proposed by the philosophic life were precisely this: that underneath it all there is nothing to think but the body? The body as origin and space of thought, the body that imagines and loves, the body that lives and dies, the body that hopes and desires?

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

But nothing to do with sex… neither voluptuousness nor eroticism nor whispering. No mixtures, few affects. The entrance into metaphysics is an exercise in self-surpassment, an effort to breathe with very little oxygen, in which the rigors of syllogisms tussle over a territory lacking emotions, lacking bodies. The philosophic reading takes place outside of ‘oneself,’ as if we had no personal involvement, as if neither time nor hunger could affect us. We quickly adopt, with Kant, the progressive path of a reason ennobled by critical consciousness, and we stop to rest a little farther on, before starting the chapter on morality. Or else we venture along the more dangerous roads of Husserlian phenomenology, snow-covered in all seasons, to the point where the landscape completely disappears, and along with it our capacity to judge. Sex will never come up. Not once. Friendship, yes, even love, missteps, lies. Sex is the silent other of philosophy—which had nevertheless taken its task to be that of conceptualizing all being, leaving nothing out, at least long ago, when metaphysics still thought it belonged to the world and thought it was nudging that same world in the direction of clarity.

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

So, read a few pages at random. Take Phaedrus, or Book VII of The Republic, the Nicomachean Ethics, Augustine’s Confessions, Descartes’s Discourse on Method, Pascal’s Pensées, Hobbes’s Leviathan, Spinoza’s Ethics, Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals, Heidegger’s Being and Time, Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, Lévinas’s Totality and Infinity, Derrida’s Specters of Marx and taste them on an empty stomach. They will provide arms for revolt, dreaming, friendship and pardon, thinking origins and history, believing and refusing to believe. But no eroticism, except perhaps as a metaphor for lost unity. And yet sex is there, wherever there is astonishment. And hunger.

Deborah Turbeville, Casa No Name

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2021 | All rights reserved

Comments