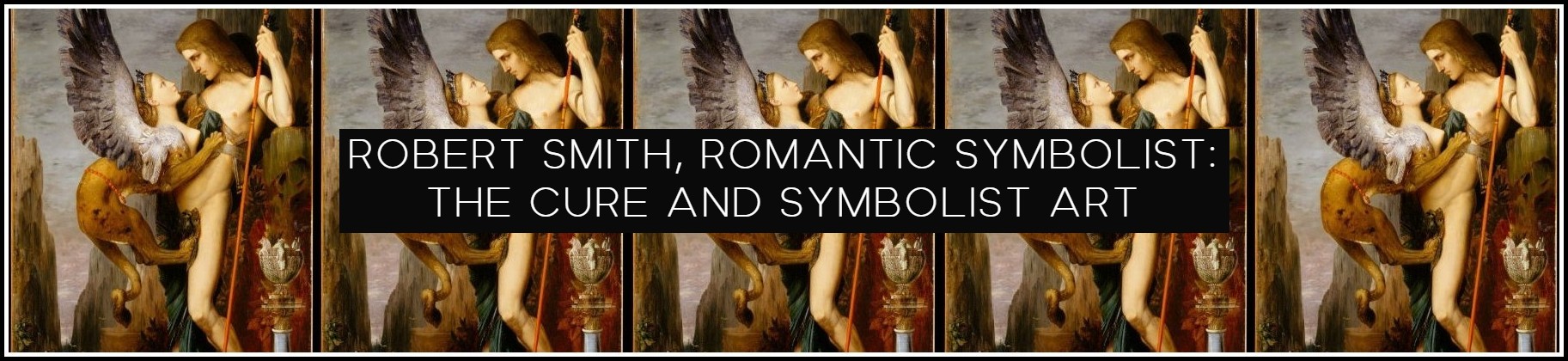

ROBERT SMITH, ROMANTIC SYMBOLIST: THE CURE & SYMBOLIST ART

Richard Jonathan

Gustave Moreau, Oedipus – Sphinx, 1864

‘Underneath the Stars’, ‘A Thousand Hours’, ‘Last Day of Summer’, ‘Out of this World’, ‘Plainsong’: ravishing in its lushness, luminously moody or darkly evocative, many a Cure song has a Symbolist aesthetic, and in particular an affinity with that movement’s Romantic sensibility.

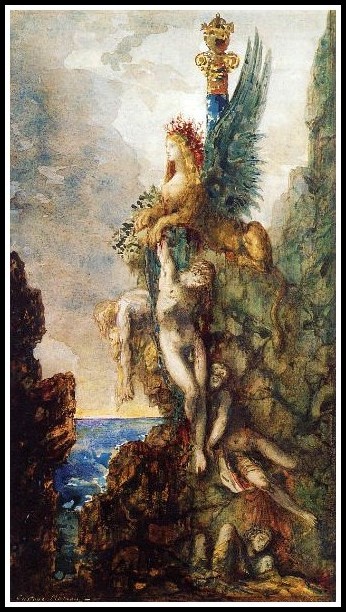

Gustave Moreau, Victorious Sphinx, 1886

Art, like religion, arose out of magic and ritual, and Symbolism (1880–1910) can be seen as a return to these roots—a rebellion, of sorts, against the realism consecrated by the rise of photography. If all art eschews descriptive, conceptual and ideological discourse in favour of the imaginative, if all art fights against alienation (if only, sometimes, by foregrounding it, by fighting poison with poison), Symbolism actively endeavours to restore to a disenchanted world wonder and awe, that dark feeling of our ‘throwness’ in the universe.

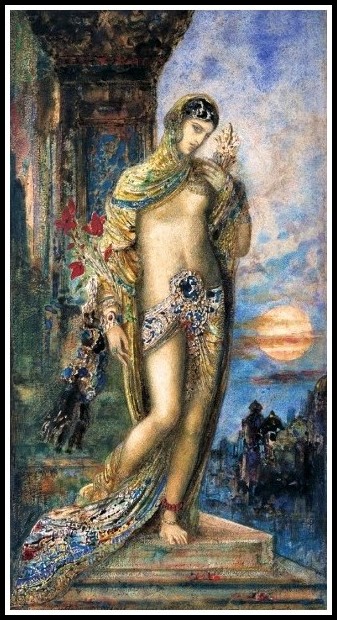

Gustave Moreau, Songs of Songs, 1893

Favouring psychological truth over discursive fact, the spiritual over the rational, it gives form to dreams and visions, rendering the ineffable palpable. Subjective experience, the primacy of emotion, the personal over the social, the artist over the engineer: Symbolism, by giving expression to the morbid and perverse, the esoteric and the erotic, provides the shadow that gives shape: against reason’s flattening light, it gives the soul relief. In a word, its mode is the mytho-poetic, and its means the axis mundi: as in all art, yes, but here the hero is no knight in shining armour, but a wanderer in bloody rags.

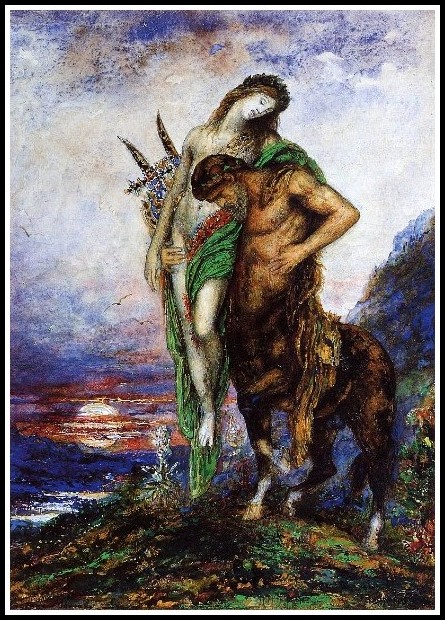

Gustave Moreau, Dead Poet – Centaur, 1890

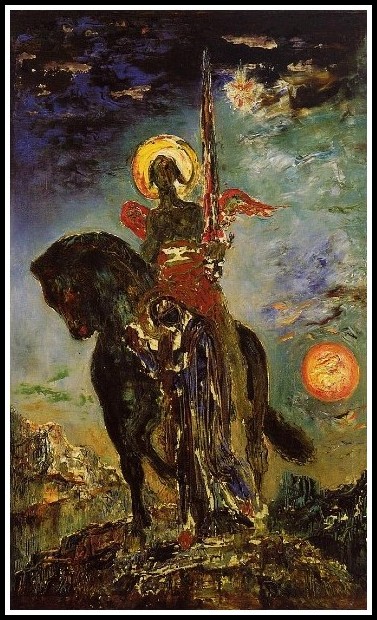

The Cure’s textured soundscapes and atmospheric elegies are Symbolist; Robert Smith’s synesthestic use of words and music to convey feelings in sound would do any Symbolist proud. When it comes to The Cure and Eros, however, we must distinguish between ‘Romantic’ and ‘romantic’: the great trilogy of Pornography, Disintegration and Bloodflowers are the band’s most Romantic albums, partaking of ‘the beauty of the Medusa’ and ‘the metamorphoses of Satan’, of ‘la belle dame sans merci’ and ‘the shadow of the divine Marquis’ (Mario Praz, The Romantic Agony). Outside the great trilogy, we do, of course, find the Romantic aesthetic again (particularly in Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me and Wish), but never in such sustained fashion.

Gustave Moreau, Fate – Death, 1890

As for small ‘r’ romantic, Robert Smith’s obsession with the theme of the couple gives it a prominent place in the Cure’s repertoire. Songs such as ‘Treasure’, ‘Apart’ and ‘Bare’ offer finely-shaded variations on the vicissitudes of the couple.

Gustave Moreau, Samson & Delilah, 1882

An aspect of Robert Smith’s art, then, is that of Romantic Symbolist. With the Cure, he has produced a set of songs that offer a supreme demonstration that ‘music is a tonal analogue of emotive life’ (Suzanne Langer, Feeling and Form). If the same could be said of any great rock song—from ‘Gloria’ to ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’, from ‘Bitch’ to ‘Debaser’—what distinguishes the Cure’s songs from these is that Robert Smith doesn’t only celebrate and purge emotion, he also drinks its poison. In this he is Symbolist, ‘consuming the poisons inside him and keeping only their quintessence’ (Rimbaud) to infuse them into his art.

Gustave Moreau, The Apparition, 1876

Symbolism, however, is but one dimension of Robert Smith’s aesthetic; in subsequent posts (see image-links below), I’ll discuss other dimensions of the Cure’s music.

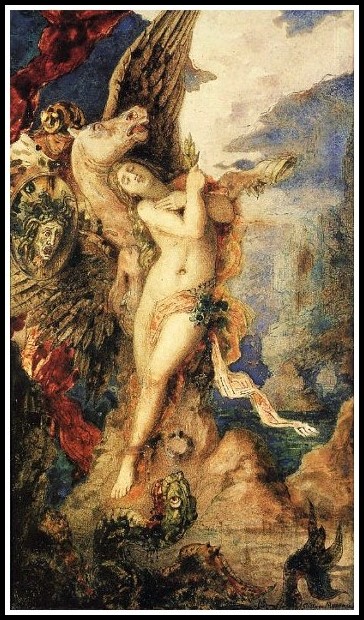

Gustave Moreau, Perseus & Andromeda, 1867-69

ROBERT SMITH & STÉPHANE MALLARMÉ: SYMBOLIST SONGWRITER & POET

Richard Jonathan

INTRODUCTION

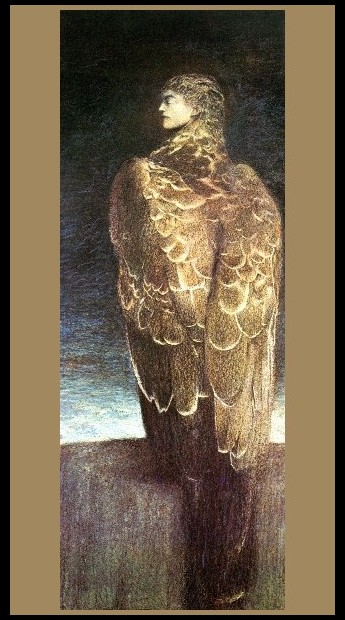

Fernand Khnopff, Medusa Asleep, 1896

More than Verlaine or Rimbaud, more even than Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé was, in the eyes of the writers of his time, the true master of Symbolist poetry, the one who incarnated its ambition and represented its spirit.

Philippe Forest, Le Symbolisme ou Naissance de la poésie moderne (Paris: Éditions Pierre Bordas, 1989) p. 31. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Let’s be clear from the get-go: It is Robert Smith as composer, not as lyricist, that bears comparison with Stéphane Mallarmé. It is Robert Smith’s* music that stands comparison with Mallarmé’s words, it is Robert Smith’s words-made-into-music that can sit beside Mallarmé’s music-in-the-form-of-words. The song and the poem, then, each in their full resonance, are our concern here.

* Wherever relevant, read ‘Robert Smith’ as ‘Robert Smith and the Cure’.

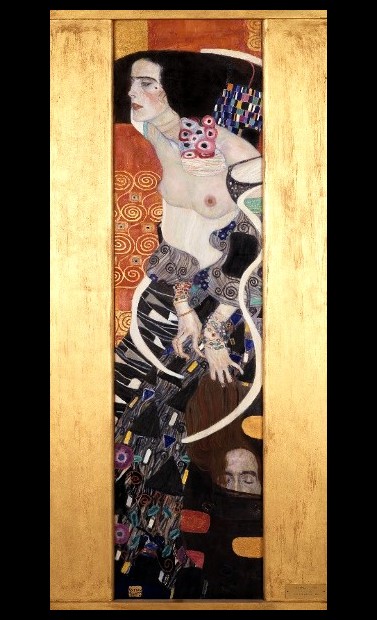

Gustave Klimt, Judith II Salome, 1919

A key tenet of Symbolism, as Mallarmé wrote, is ‘to portray not the thing, but the effect it produces’. Moreover, he asserted, to name an object is to foreclose the pleasure to be had in guessing it: to suggest it, that is the ideal. For Mallarmé, poetry must embody enigma, and only when it trades the expression of exterior reality for the invention of its own, only when it foregoes discursiveness in favor of allusiveness, can it hope to attain the condition of music, the supreme art.

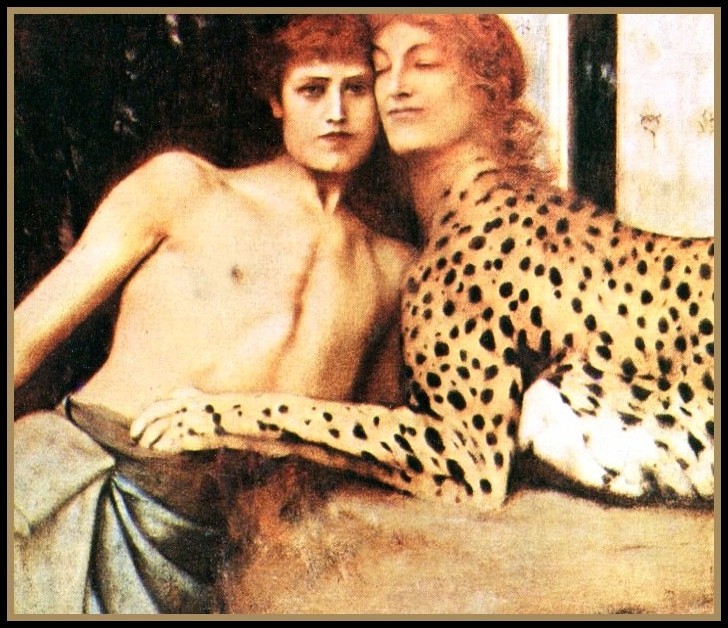

Fernand Khnopff, The Caress, 1896 (detail)

On the page, Robert Smith’s lyrics sometimes come across as sloppy and trite. They don’t ‘read well’, there’s nothing ‘poetic’ in their construction; it seems, sometimes, they are but vehicles for ‘banalities’. And this, paradoxically, is precisely why Robert Smith is an excellent lyricist. To paraphrase Grace Jones, his lyrics are not perfect (on the page), but they are perfect for the Cure’s music; they are not perfect (for the reader rooted in a blind-spot), but they are perfect for the singer who will transform them. All in all, they are not perfect for the classically conditioned eye, but they are perfect for the ear attuned to the sublime.

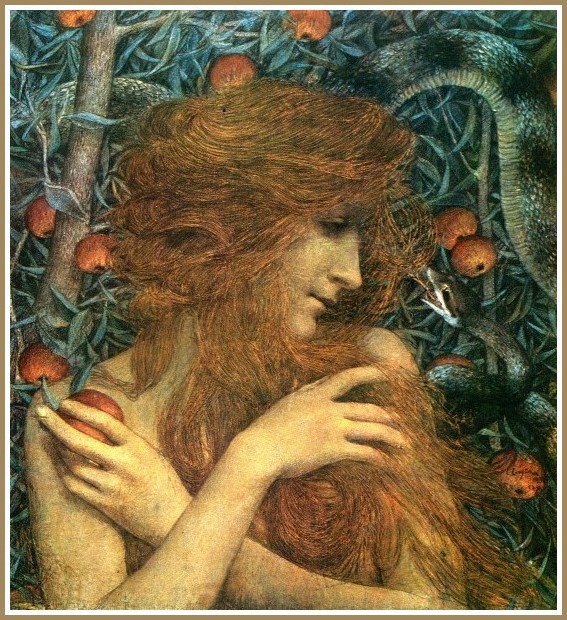

Lucien Levy-Dhurmer, Eve, 1896

Words, in Robert Smith’s lyrics, often denote an exterior reality; often, through dialogue, they sketch a situation (see, for example, ‘Bare’). To denote ‘the thing’ (the object of the song’s concern)—that is all the Cure’s approach requires the lyric to do, for it is the music that portrays the effect the thing produces. Given this, for Robert Smith to write a highly-wrought, stand-alone lyric would not only be counterproductive, but would actually degrade the artistry of the song. Think of his lyrics as base metals for the alchemy of the music; think of his words as the finger pointing at the moon: the holistic experience of music wherein words are subsumed in song.

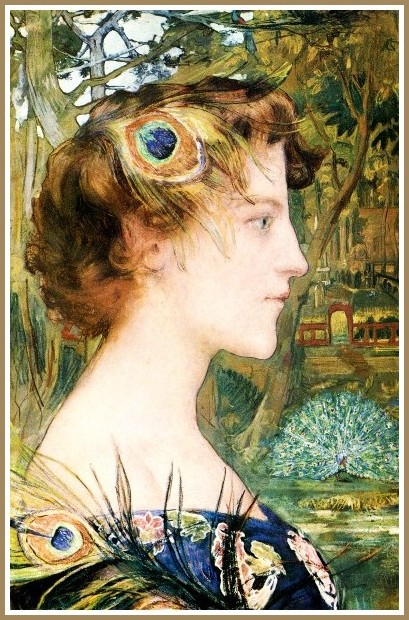

Edgar Maxence, Peacock Profile, 1896

Music, necessarily, is inherently Symbolist: it cannot denote, it cannot be discursive. Still, it is fair to say that Wagner’s music is more Symbolist than Puccini’s, that the Cure’s music is more Symbolist than, say, that of Simple Minds. Why? How does one decide? Besides the obvious predilection of Wagner and the Cure for Symbolist (in addition to Romantic) themes—the beauty of the Medusa and the metamorphoses of Satan, la belle dame sans merci and the shadow of the divine Marquis—and Symbolist tonalities—the morbid and the perverse, the esoteric and the erotic, and a certain self-indulgent world-weariness (brilliantly deconstructed by Sartre in his study of Baudelaire)—there are three key considerations. One: the degree of allusiveness, expressed in what we experience as ‘atmosphere’ or ‘moodiness’. Two: the degree of ambiguity or ambivalence, expressed in what we hear as ‘cross-currents’ or ‘heightened tensions’ in the music and words. Three: the degree of subjectivity, what we experience as a foregrounding of a narrative ‘I’.

Fernand Khnopff, Who Shall Deliver Me? 1890

All these elements, making for a heightened appreciation of the Symbolist aesthetic, I leave you now to discover in the three pairs of Cure songs and Mallarmé poems below. I trust you will find the affinities and parallels between the songs and the poems; I trust both the Symbolist songwriter and the Symbolist poet will enchant you: all you need is memory and imagination, artistic intelligence, and openness to the sublime.

Jean Delville, Medusa, 1893

BLOODFLOWERS

Robert Smith, Bloodflowers, 2000

‘This dream never ends’, you said

‘This feeling never goes

The time will never come to slip away’

‘This wave never breaks’, you said

‘This sun never sets again

These flowers will never fade, never fade’

‘This world never stops’, you said

‘This wonder never leaves

The time will never come to say goodbye’

‘This tide never turns’, you said

‘This night never falls again

These flowers will never die, never die, never die

These flowers will never die, never die’

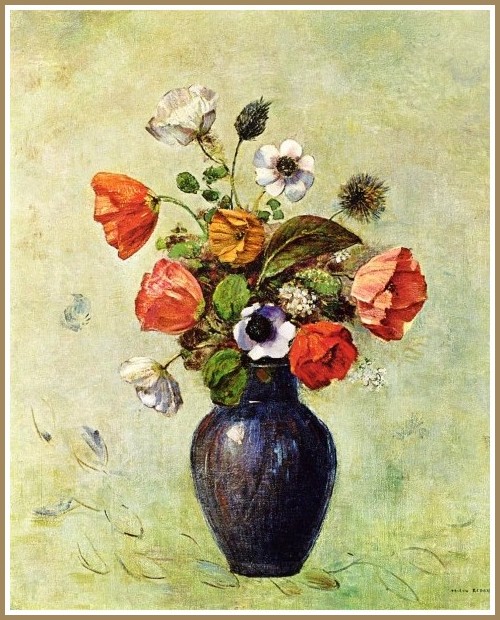

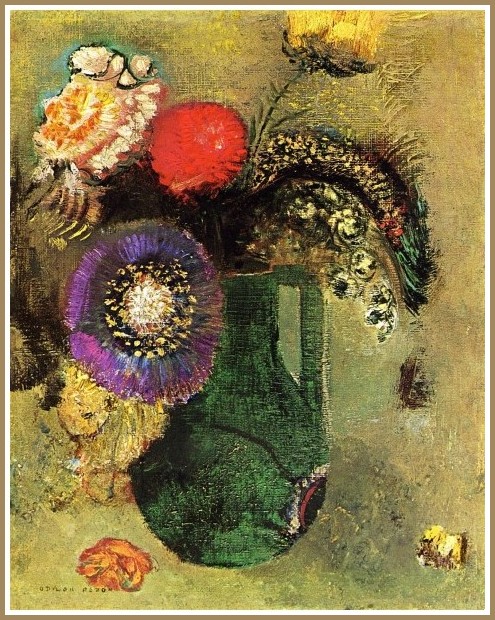

Odilon Redon, Poppies and Anemones in a Vase, 1914

‘This dream always ends’, I said

‘This feeling always goes

The time always comes to slip away’

This wave always breaks’, I said

‘This sun always sets again

These flowers will always fade’

‘This world always stops’, I said

‘This wonder always leaves

The time always comes to say goodbye’

‘This tide always turns’, I said

‘This night always falls again

And these flowers will always die, always die, always die

These flowers will always die’

Odilon Redon, Flowers in a Green Vase, 1905

Between you and me it’s hard to ever really know

Who to trust, how to think, what to believe

Between me and you it’s hard to ever really know

Who to choose, how to feel, what to do

Never fade, never die

You give me flowers of love

Always fade, always die

I let fall flowers of blood

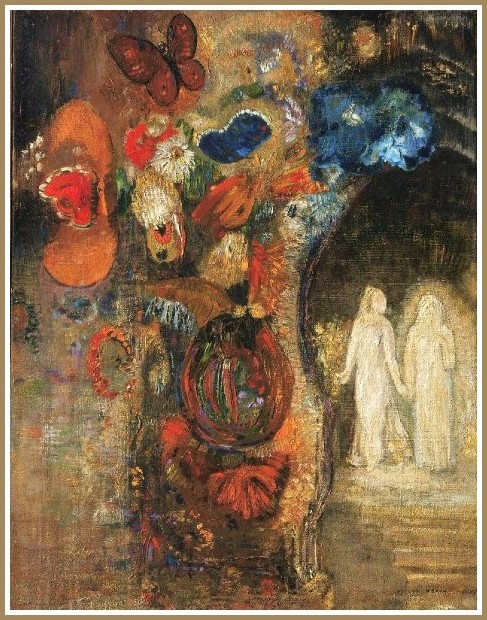

Odilon Redon, Flowers, 1903

THE FLOWERS

Stéphane Mallarmé, 1864 | Translated by Daisy Aldan

From the golden avalanches of the ancient azure,

On the primal day, and from the eternal snow of the stars

Once you released the great calyxes for

The still youthful earth, virgin of disasters,

The fauve gladiolus, with the slender throated swans,

And the divine laurel of exiled souls

Vermilion like the pristine toe of a Seraph

Which the modesty of trampled dawns crimsons,

The hyacinth, the myrtle with its heavenly flash

And, like the flesh of woman, the cruel

Rose, flowering Herodias of the limpid garden,

She who is bedewed with savage and lustrous blood!

Odilon Redon, Apparition, 1905–10

And you fashioned the sobbing white of the lily

Which rolling over the seas of sighs that it brushes,

Across blue incense of pale horizons

Dreamily ascends toward the weeping moon!

Hosannah on the cithem and in the censers,

Our Lady, Hosannah from the garden of our limbos!

And may the echo cease during the celestial evenings

Ecstasy of glances, nimbus scintillations!

O Mother who created in your mighty and righteous bosom,

Calyxes balancing the future phial,

Majestic flowers with balsamic Death

For the weary poet, wasted by life.

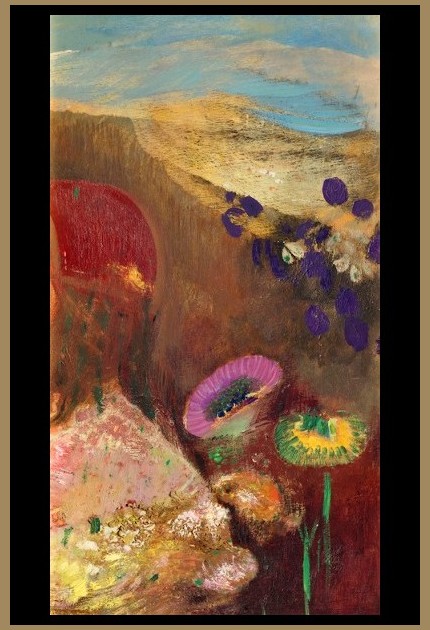

Odilon Redon, Strange Flowers, 1910

‘THE FLOWERS’: INTERPRETATION BY DAISY ALDAN

‘Les Fleurs’ is one of Mallarmé’s exquisite lyrics, which one experiences as music. It is addressed to the Great Mother of Creation (Isis-Sophia-Maria). Stanza one evokes the purity of primal creation, time of golden avalanches and the original rich flora. Stanza two unfolds fauve gladioli with their swans’ throats (swans symbolizing spiritual beings), the divine laurel (plant of Grecian Heroes) and the vermilion of dawn whose skies evoke the Seraphim. Stanza three introduces the Fall, time of metamorphosis: The hyacinth, the myrtle, associated with death, and the ‘cruel rose’ (personification of Herodias, who plotted the beheading of John the Baptist). Stanza four presents her juxtaposition—the lily (who is associated with the weeping and suffering Maria). The gold and vermilion have transformed to seas of sighs, blue incense and pale horizons and a weeping moon—an evocation of the Crucifixion. Stanza five takes a new direction: The poet praises the cithern and the censers, associated with religious ritual. In spite of being bound in the limbos of our ‘ennui,’ we send up ‘Hosannahs’ in recognition of such celestial beauty, says the poet. Stanza six presents us with a sudden shock: The exquisite creations of the Great Mother also contain poison which the despairing poet may imbibe to kill himself.

From Stéphane Mallarmé, To Purify the Words of the Tribe: The Major Verse Poems of Stéphane Mallarmé, with ‘Un Coup de dès jamais n’abolira le hasard’. Translation from the French and expositions by Daisy Aldan (USA: Sky Blue Press, 1999)

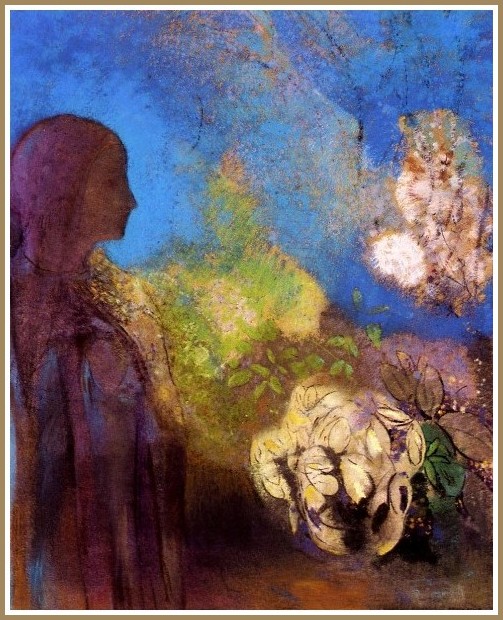

Odilon Redon, Girl with Chrysanthemums, 1905

THE SAME DEEP WATER AS YOU

Robert Smith, Disintegration, 1989

Kiss me goodbye

Pushing out before I sleep

Can’t you see I try?

Swimming the same deep water as you is hard

The shallow drowned lose less than we

The strangest twist upon your lips

And we shall be together, and we shall be together

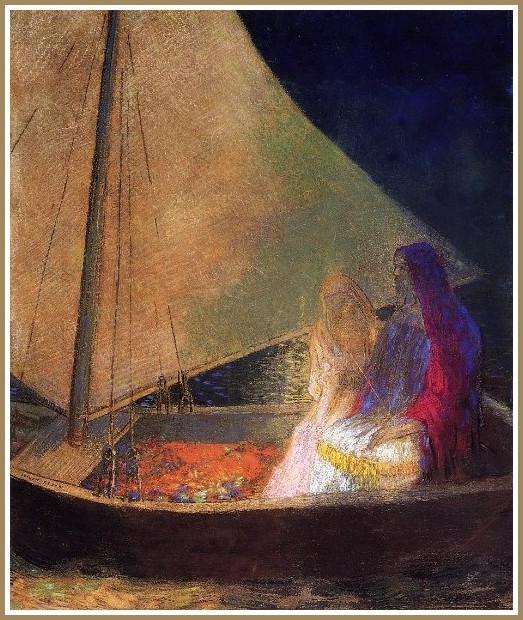

Odilon Redon, Boat with Figures

Kiss me goodbye

Bow your head and join with me

And face pushed deep, reflections meet

The strangest twist upon your lips

And disappear, the ripples clear

And laughing break against your feet

And laughing break the mirror sweet

So we shall be together, so we shall be together

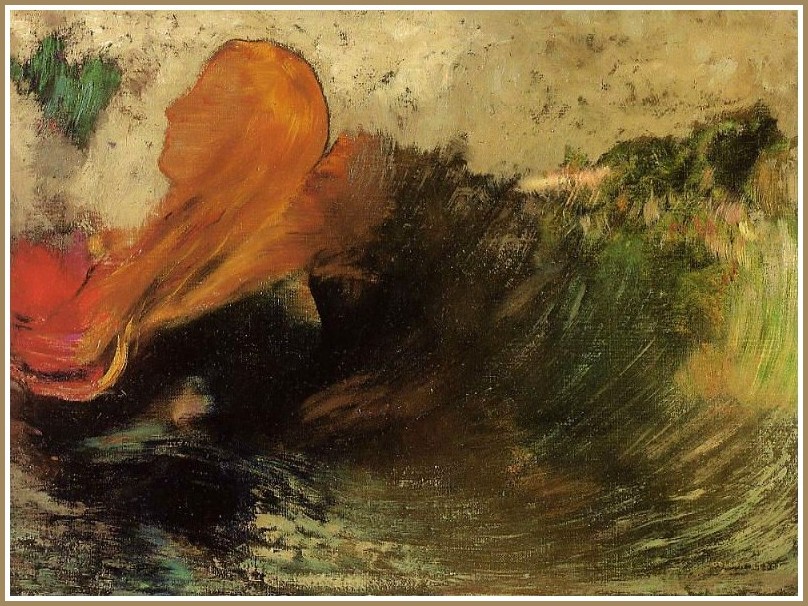

Odilon Redon, The Death of Ophelia

Kiss me goodbye

Pushing out before I sleep

It’s lower now, and slower now

The strangest twist upon your lips

But I don’t see, and I don’t feel

But tightly hold up silently

My hands before my fading eyes

And in my eyes your smile

Odilon Redon, Boat – Grey

The very last thing before I go

The very last thing before I go

The very last thing before I go

I will kiss you, I will kiss you

I will kiss you forever on nights like this

I will kiss you, I will kiss you

And we shall be together

Odilon Redon, Ophelia, n.d.

SUMMER SADNESS

Stéphane Mallarmé, 1864 | Translated by Daisy Aldan

O sleeping wrestler, on the sand, the sunlight

Heats a languorous bath in the gold of your hair

And, inhaling the incense on your hostile cheek,

It mingles an amorous potion with your tears.

The immutable calm of this white blaze

(O my timid kisses) made you sadly declare,

‘We will never be a single mummy

Beneath the ancient desert and the happy palms!’

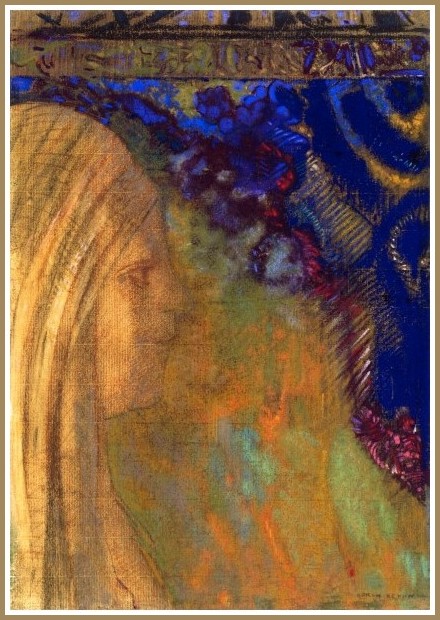

Odilon Redon, Profile with Tapestry

But your tresses are a tepid river

Wherein our soul obsessed may drown without trembling

And find the Void which you do not fathom!

I will taste the kohl wept by your tears,

To see if it can bestow on this heart you have wounded

The indifference of the azure, and stones.

Odilon Redon, Red Thorns

‘SUMMER SADNESS’: INTERPRETATION BY DAISY ALDAN

This sonnet was addressed to Mallarmé’s wife. On a summer afternoon, they have been lying on the sand, making love. There has been no consummation, and the woman lies asleep while the hot sun in her loosened blond hair and on her cheek causes them to emit a heady fragrance. His kisses were not passionate, and tearfully she declared that she and he would never be as one. We note again Mallarmé’s obsession with golden tresses. He says that it is enough for him to drown his obsessed soul in her hair, that he is able to appreciate a reality in a way which she is unable to understand. Perhaps the mascara mingling with her tears, which he will ‘taste,’ will help him achieve the indifference of the distant dispassionate azure and the insensitive stones.

From Stéphane Mallarmé, To Purify the Words of the Tribe: The Major Verse Poems of Stéphane Mallarmé, with ‘Un Coup de dès jamais n’abolira le hasard’. Translation from the French and expositions by Daisy Aldan (USA: Sky Blue Press, 1999)

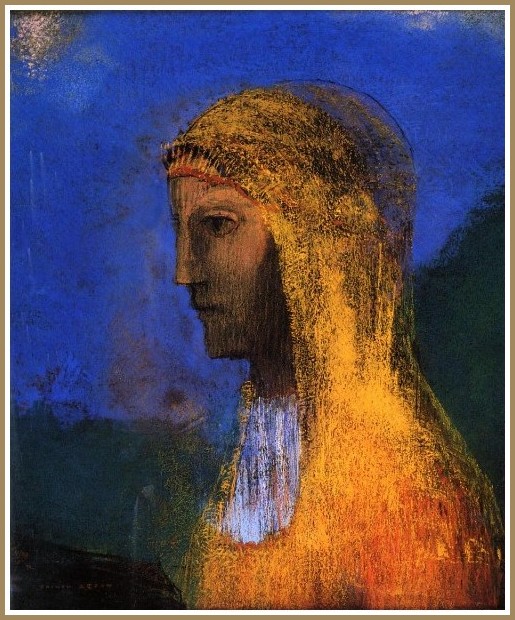

Odilon Redon, Druidess

SINKING

Robert Smith, The Head on the Door, 1985

I am slowing down

As the years go by

I am sinking

So I trick myself

Like everybody else

The secrets I hide

Twist me inside

They make me weaker

So I trick myself

Like everybody else

I crouch in fear and wait

I’ll never feel again

If only I could, if only I could

If only I could remember

Anything at all

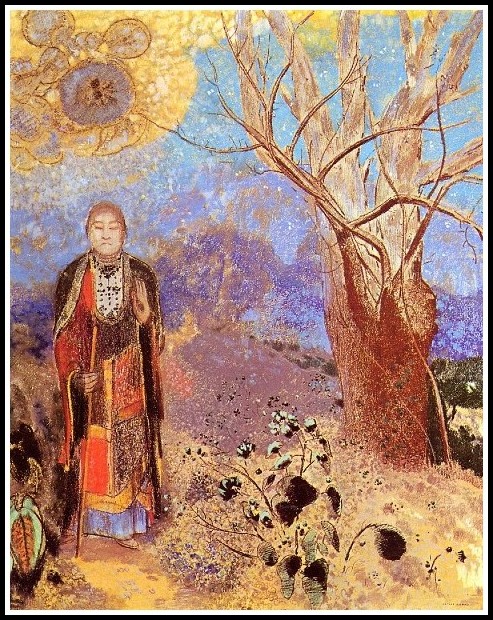

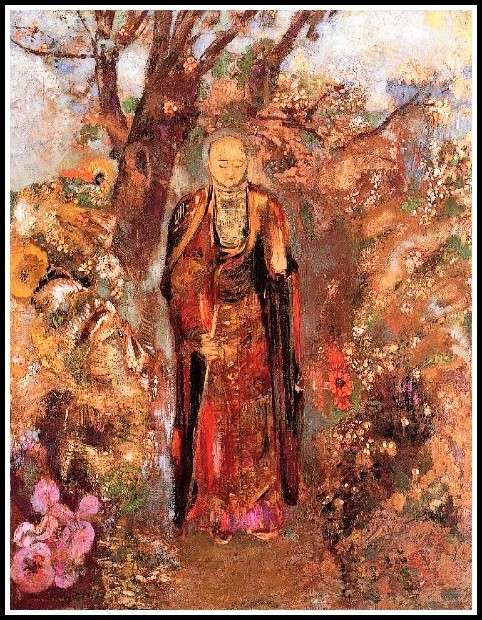

Odilon Redon, Buddha, 1906

WEARY OF THE BITTER REPOSE

Stéphane Mallarmé, 1864 | Translated by Daisy Aldan

Weary of the bitter repose where my indolence offends

A glory for which once I fled adorable

Childhood of rose-filled groves beneath the azure

Of Nature, and more than seven times weary of the onerous pact

Of digging, sleepless nights, a new groove

In the miserly and frozen terrain of my brain,

Sexton without pity for sterility,

—Visited by roses, what shall I say to this Dawn,

O Dreams, when, fearful of its own livid roses,

The vast cemetery will unite the empty graves?—

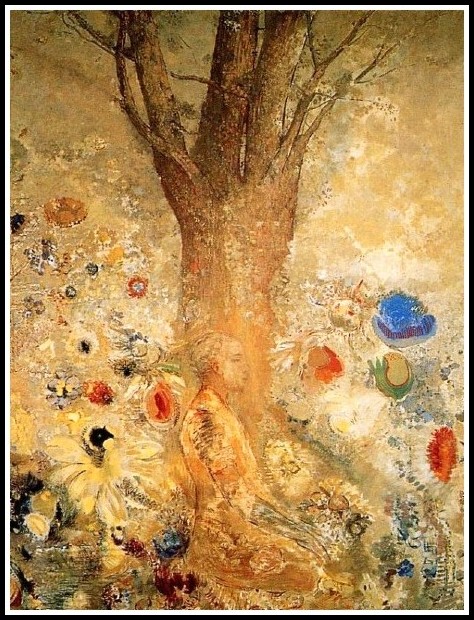

Odilon Redon, Buddha Among the Flowers, 1907

I would leave voracious Art of a cruel

Country, and scorning the outworn reproaches

Of my friends, the past, genius,

And my lamp which knows of my anguish,

Imitate the Chinese of limpid and delicate heart

Whose unsullied ecstasy lies in painting

On his cup, white as moon-ravished snow

The death of a bizarre flower which perfumes his life

Transparent, the flower he felt as a child

Incised on the blue filigrane of his soul.

And with a death like the sole dream of the Sage,

Serenely, I’ll choose a youthful landscape

Which I’d paint again on the cups, with an absent air.

A line of blue, thin and pale would be

A lake, amid the sky of virgin porcelain,

A clear crescent moon lost in a white cloud

Dips its tranquil horn in the ice of the waters,

Not far from three great emerald eyelashes, reeds.

Odilon Redon, Buddha in His Youth, 1907

‘WEARY OF THE BITTER REPOSE’: INTERPRETATION BY DAISY ALDAN

In a mood of depression, invaded by indolence, the poet feels unworthy of his former ideals and of the task which he once set for himself, one requiring giant effort and renunciation of usual pleasures; and weary of his painful struggle to overcome this sterility, he still dreams of flowering poems, but experiences only the abyss where (without sunlight) only livid ghost-like flowers (creations) bloom. He longs to escape from the cruel world of the present where he has been maligned and rejected by his contemporaries, and also from the futile vigil at his ‘lamp’ where he spent sleepless nights attempting to create. He longs to return to a previous exotic era when Chinese painters did not portray subjective passionate experiences, but comprehended essence, objectivity, silence, white spaces, and the emptiness which permits the spirit to enter; they used delicate evocative sparse imagery which achieved a transparency through which the spirit might be experienced. This ‘unsullied ecstasy’ was like the unsullied dream of childhood. This way, in his poems, he would, as on a porcelain cup with suggestive spare color and line, evoke universal essence beyond the physical image.

From Stéphane Mallarmé, To Purify the Words of the Tribe: The Major Verse Poems of Stéphane Mallarmé, with ‘Un Coup de dès jamais n’abolira le hasard’. Translation from the French and expositions by Daisy Aldan (USA: Sky Blue Press, 1999)

Yuan Yunfu, Untitled, Xiamen (China)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2021 | All rights reserved

Comments