Signs and Non-Signs: Changing Strategies of Representation

DEGAS’ DEPICTION OF WOMEN: FROM DESCRIPTION TO EVOCATION

Richard Kendall

Richard Kendall (1946-2021), graduate of the Central School of Art and Design and the Courtauld Institute of Art, was a renowned Degas scholar.

From Richard Kendall, “Signs and Non-Signs: Degas’ Changing Strategies of Representation”

in Richard Kendall & Griselda Pollock, editors, Dealing with Degas: Representations of Women and the Politics of Vision (London: Pandora Press, 1992) pages 186-201

Degas, Self-Portrait in Library, 1895 (detail) | Degas, Woman Seated beside a Vase of Flowers, 1865 | Degas, Self-Portrait with Zoé Closier, 1895 (detail)

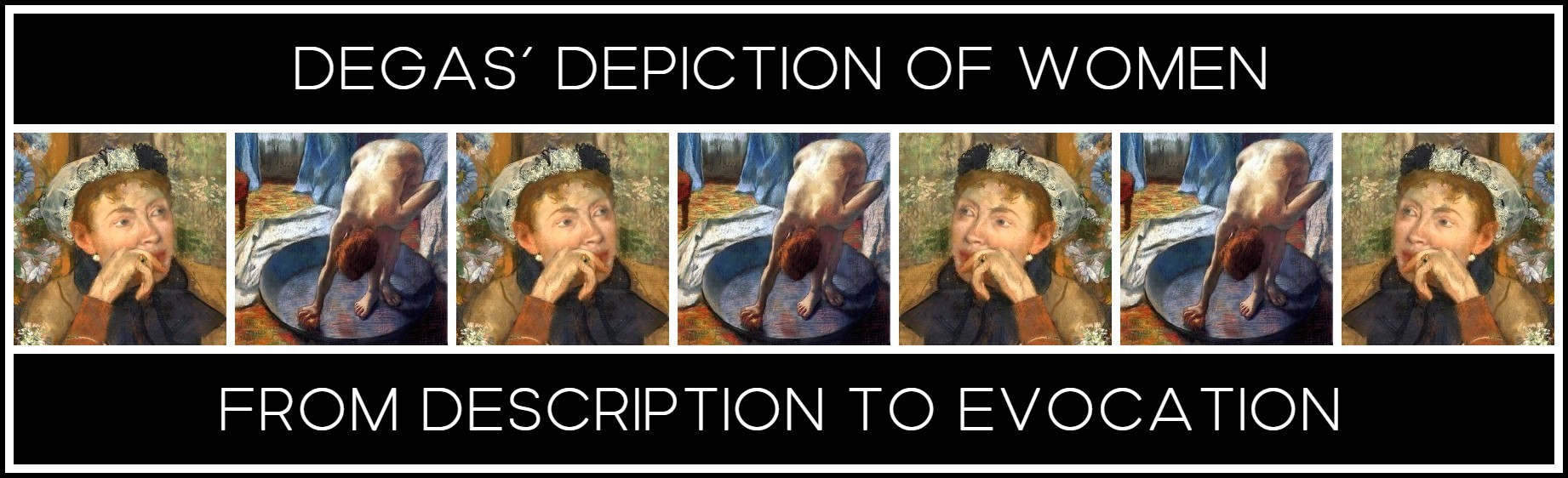

Amongst the many debates surrounding Degas’ images of women, surprisingly few have been concerned with the visual structures of the pictures themselves and the ways in which they constrain or direct the viewer’s response to the subject. Whilst the analysis of pictorial language is still a contested and ill-defined procedure, there is every reason to believe that it should be part of any approach to Degas’ imagery. His own contemporaries repeatedly singled out the mechanisms of Degas’ pictures for comment, hinting that the asymmetrical compositions, discontinuous spaces, curiosities of focus and oddities of pose were signs of a new sensibility, or of a changing dialogue between subject and spectator. There is also evidence that the artist himself had an unusually deliberate approach to such matters and that some of these signs and structures were adopted, and subsequently discarded, as part of a self-conscious strategy of representation. Though we are not entitled to assume that these structures had uncomplicated meanings for either the artist or his contemporaries, or that such an analysis will grant a privileged access to a modern audience, there remains an urgent need to identify, scrutinize and evaluate them. The tendency to discuss subject-matter without reference to pictorial organization; to gather Degas’ work into undifferentiated groupings, such as the brothel monotypes or pastels of the female nude, regardless of their discontinuities; to shy away from contact with original works of art and to neglect considerations of scale, composition and technique; and to disregard the developmental nature of Degas’ pictorial syntax, can all vitiate what might otherwise be productive speculation.

Degas, Dans un café (L’Absinthe) [The Absinthe Drinker], 1876

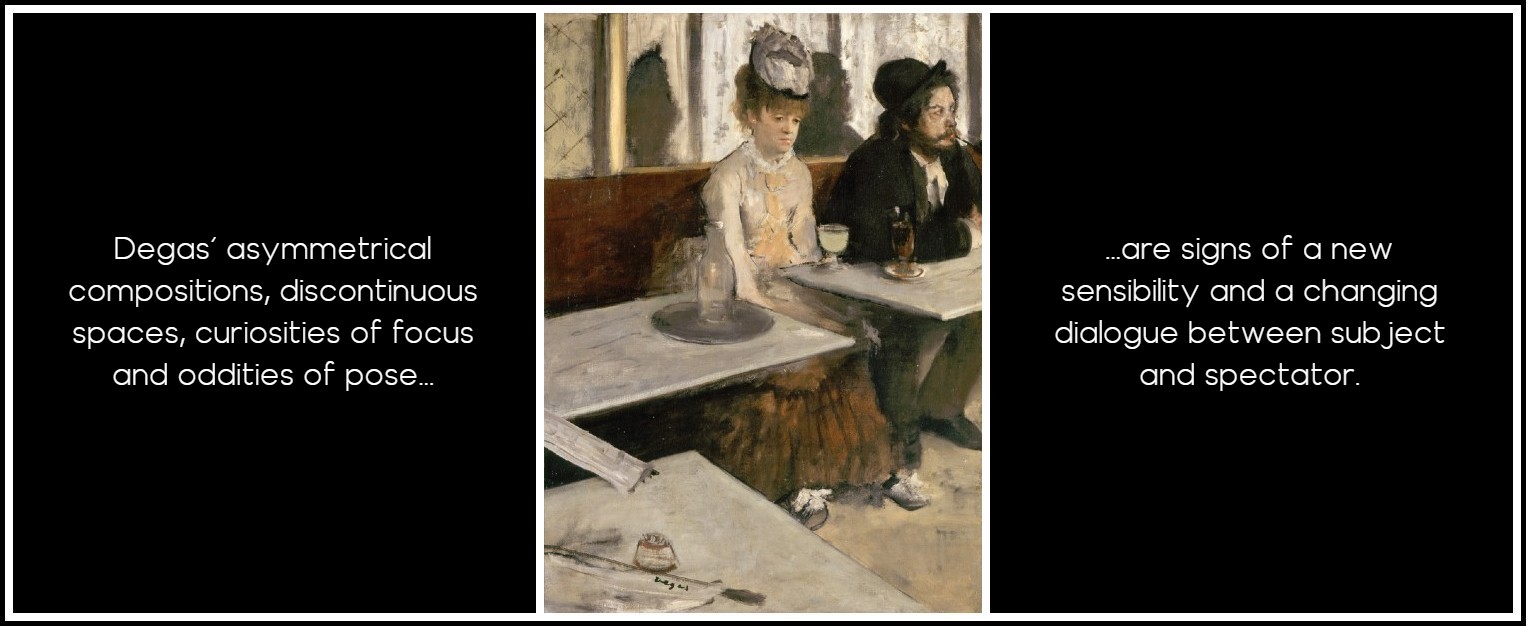

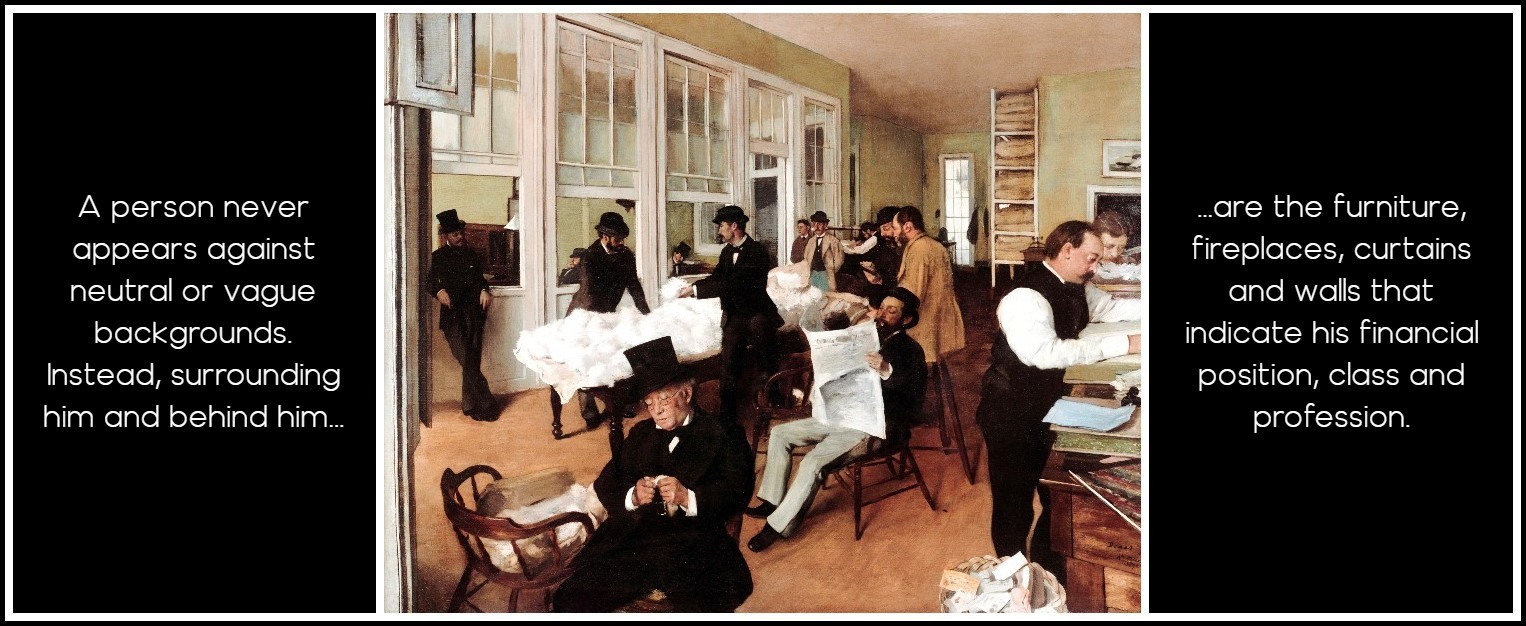

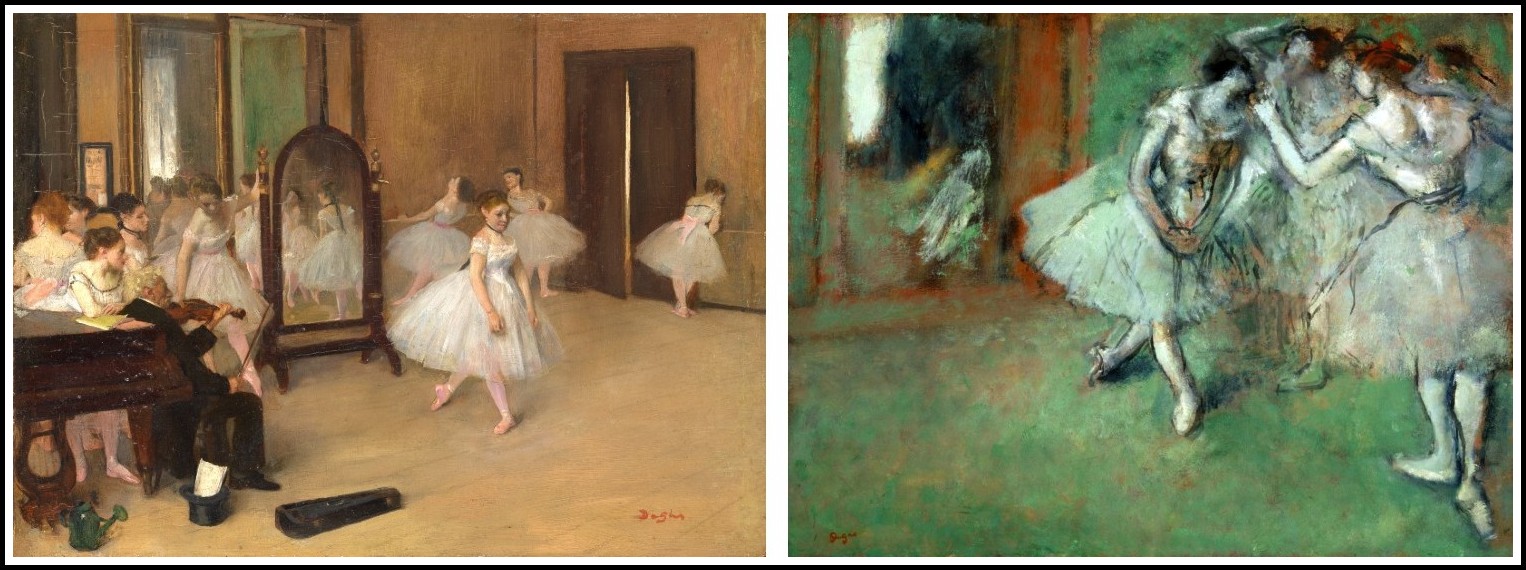

An analysis of a group of Degas’ images of women from the 1870s helps to establish some of the visual procedures which characterized his work at the beginning of his public career. The Dance Class, one of the artist’s pioneering ballet pictures, was executed in 1871 and exhibited at the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874. The space depicted is both broad and deep, with a clear demarcation between foreground, middle distance and background. The room itself is precisely described, from its high doors and tall mirrors to the bare expanse of its rehearsal floor and unadorned walls. Within this spacious and articulate arena, the artist has introduced a number of relatively small figures and a generous array of properties. Nine ballet-dancers (and their attendant reflections) are carefully differentiated from each other in pose, costume and hair-colouring, whilst an elderly musician presides over a sombre still-life of piano, watering-can, top hat and violin case. Throughout this unusually small painting, detail is sharply focused, as if the artist aimed to concentrate the maximum amount of visual information into its modest confines.

Degas, The Dance Class, 1871

A few days before the Dance Class was put on show in 1874, Degas wrote to his friend James Tissot to persuade him to participate in the forthcoming exhibition. Though Degas and his colleagues had yet to decide on a name for themselves or their exhibition, the letter to Tissot makes Degas’ perception of the event very clear. He wrote; ‘The Realist movement no longer needs to fight with the others, it already is, it exists, it must show itself as something distinct, there must be a salon of realists’. While Degas never defined what ‘realism’ meant to him, the Dance Class and the nine other pictures he exhibited in 1874 provide a number of clues. Each of the subjects chosen (four scenes of the ballet, three of the race-track, two of laundresses and one aprés le bain) is conspicuously urban and contemporary, and each stresses the informal nature of the action depicted. Most of the pictures show wide, panoramic vistas and, like the Dance Class, incorporate a number of small figures in a deep and minutely described space. Visual definition is sharp and continuous, with costumes, furnishings and paraphernalia carefully documented and rooms or landscape settings crisply focused. So insistent was the visual documentation that some critics noted it adversely; even Emile Zola, the champion of descriptive Realism in the novel, suggested that Degas spoiled his pictures by an excessive attention to detail.

Degas, At the Races in the Countryside, 1869

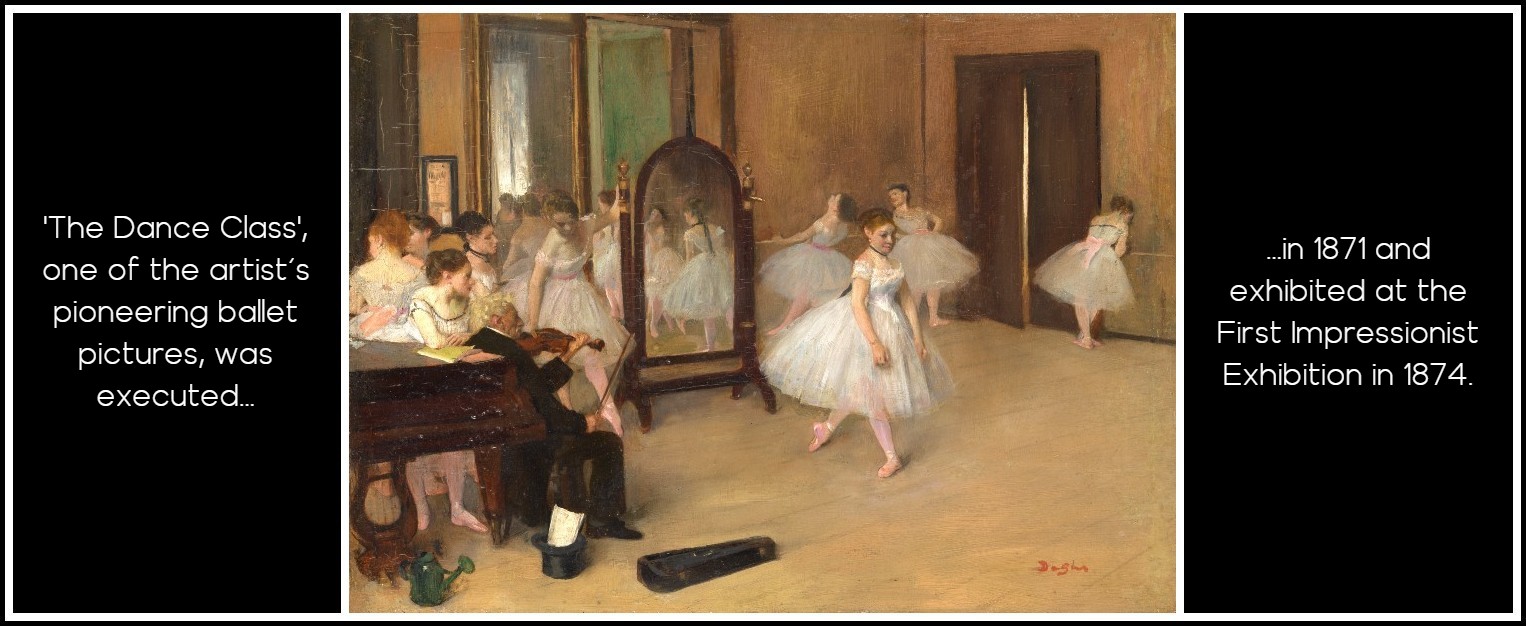

By the time of the Second Impressionist Exhibition of 1876, Degas had met and befriended one of Zola’s admirers, the novelist and critic Edmond Duranty. In his essay La Nouvelle Peinture, published in 1876 soon after the opening of the exhibition, Duranty quoted with approval Zola’s claim that ‘Science requires solid foundations, and it has returned to the precise observation of facts. And this thrust occurs not only in the scientific realm but in all fields of knowledge’. In the field of the visual arts, this ‘precise observation of facts’ had a number of important implications. Duranty himself wrote that: ‘We will no longer separate the figure from the background of an apartment or street. In actuality, a person never appears against neutral or vague backgrounds. Instead, surrounding him and behind him are the furniture, fireplaces, curtains and walls that indicate his financial position, class and profession. The individual will be at a piano, examining a sample of cotton in an office, or waiting in the wings for the moment to go onstage, or ironing on a makeshift table.’

Degas, Cotton Office in New Orleans, 1874

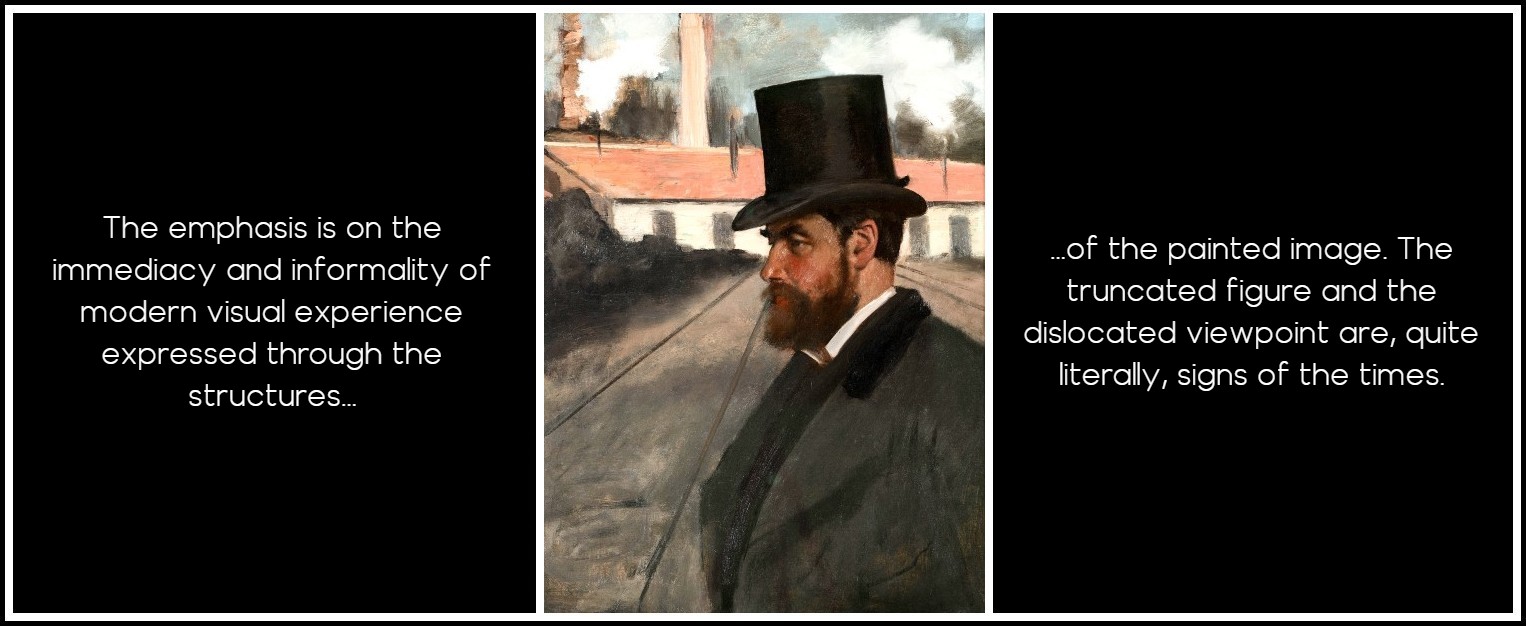

It is clear that Duranty had Degas’ own pictures in mind, both in this passage and in the wider argument of his essay. For both writer and artist, the description of ‘backgrounds’ helped to define the narrative and identify its protagonists. Deep space, clear lighting and a high degree of detail encouraged the ‘precise observation of facts’ and enabled the artist to characterize his subject through gesture, physiognomy and costume. Duranty went on to describe the other pictorial strategies appropriate to the New Painting, again echoing known pictures by Degas, ‘the large expanse of ground or floor in the immediate foreground’, the viewpoint that ‘is sometimes very high, sometimes very low’ and the figure that ‘is not shown whole, but often appears cut off at the knee or mid-torso, or cropped lengthwise’. Here the emphasis is on the immediacy and informality of modern visual experience expressed through the structures of the painted image; the truncated figure and the dislocated viewpoint are, quite literally, signs of the times.

Degas, Henri Rouart in front of his Factory, 1875

The significance of Degas’ imagery in the 1870s becomes even more evident when it is compared with his work from subsequent decades. His Group of Dancers was painted more than twenty-five years after the Dance Class, but its principal subject is effectively the same. The central ballerina is a direct descendant of the corresponding figure in the 1871 painting, while the lateral group of dancers, the asymmetrical composition and the mirror or doorway all recall the earlier work. As visual structures, however, the two images differ radically. In the Group of Dancers, as so often in his later work, Degas has moved closer to his subject, allowing the figures to fill the frame and confining them to a shallow foreground space. As a direct consequence, the room itself is largely excluded from the picture rectangle, along with the furniture, accessories and supporting cast so much in evidence in the Dance Class. Not only have such crucial indicators been removed, but the little that remains is so lacking in definition that its significance is far from clear. The depicted dancers might be engaged in exercise, in relaxation or even in dancing, but they lack facial features and all other signs of individuality; even the ominous void to their right is only recognizable as a mirror by comparison with earlier versions of the scene. In place of the ‘precise observation of facts’ we have ambiguity and inference, set against one of those ‘neutral and vague backgrounds’ that Duranty had earlier deplored.

Degas, The Dance Class, 1871 | Degas, Group of Dancers, 1898

The tendency for Degas’ images of dancers to become less informative and less historically specific is paralleled in many of his other female subjects. While Degas’ art is not entirely consistent in its development, and important exceptions to this tendency can be found, other themes show a similar progression from the inclusion of signs of narrative and identity towards their exclusion. Beach Scene, shown by Degas in the Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877, has the deep space, panoramic sweep and sharp focus already identified in the slightly earlier Dance Class. Like that picture, background and accessories are used to define the protagonists, though in Beach Scene the figures themselves are both more prominent and more informative. Not only are their costumes, limbs and deportment more expressive of their roles, but their faces are particularized and suggestive. The maid’s weather-beaten complexion contrasts with the paleness of the child’s, while the older woman’s heavy features, which reflect a stereotypical view of working-class appearance, accentuate the delicacy and refinement of her protégée. Such attention to physiognomy is conspicuous in Degas’ work during the 1870s and early 1880s, but becomes noticeably less common in subsequent years.

Degas, Beach Scene, 1877

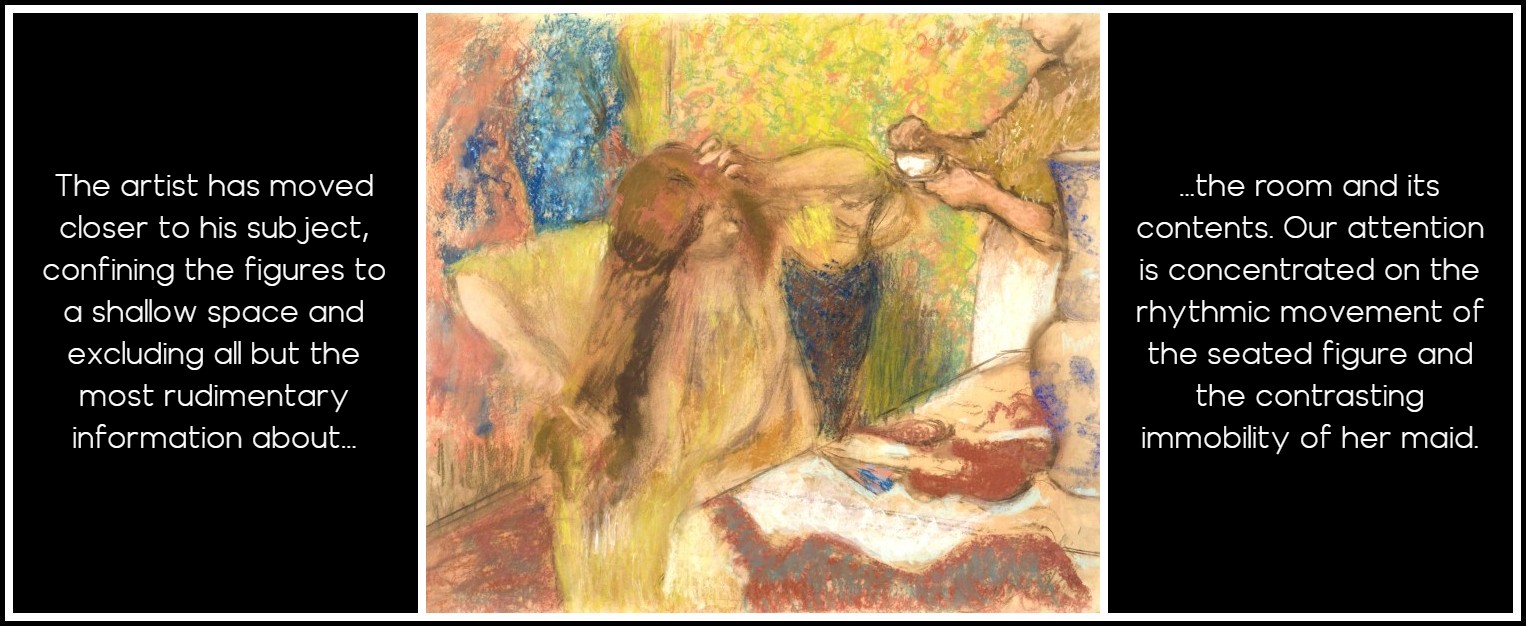

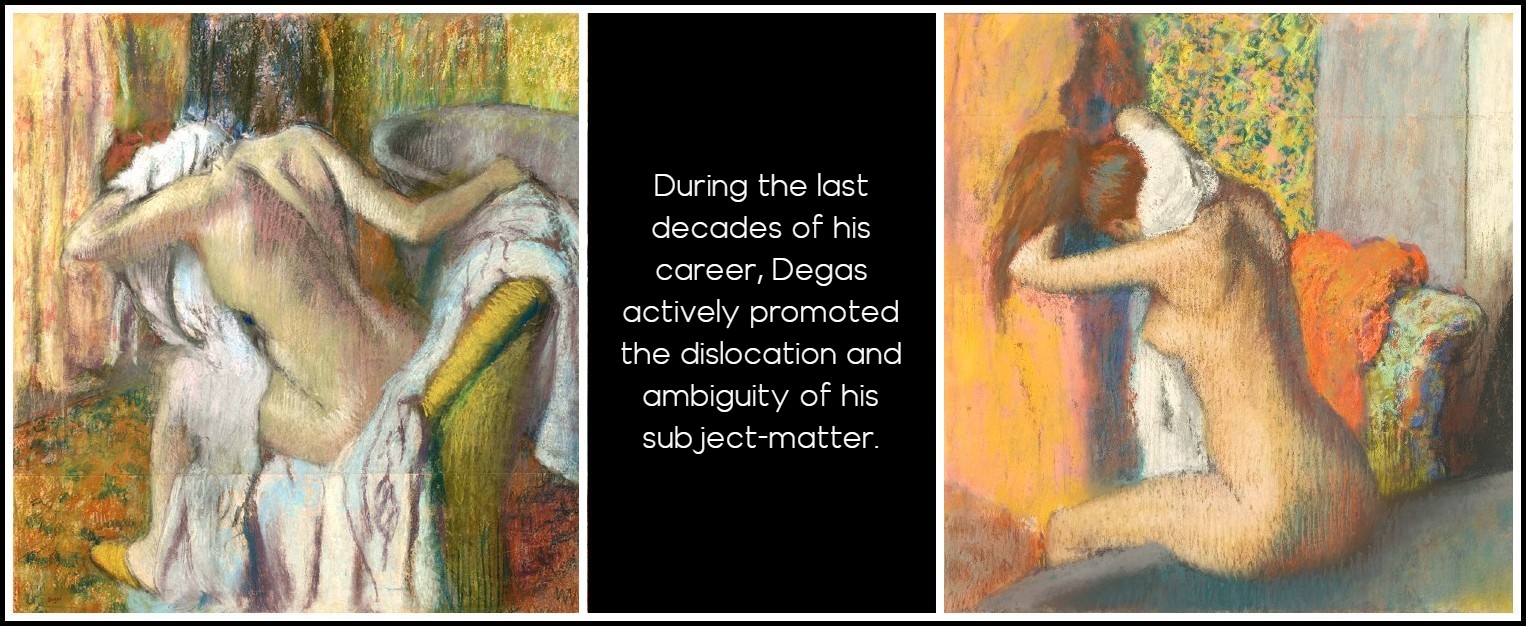

A comparable scene from the 1890s, Woman at her Toilette, shows a later variant of the hair-combing motif. Once again, the artist has moved closer to his subject, confining the figures to a shallow space and excluding all but the most rudimentary information about the room and its contents. While the picture is at least as complex in its implications as the earlier Beach Scene, our attention is here concentrated on the rhythmic movement of the seated figure and the contrasting immobility of her maid. More remarkably, both women are effectively featureless, the maid’s head cropped by the edge of the picture and the face of her mistress averted and lost in a blur of pastel. Though their class identities are still mutely signalled through costume and posture, these two women, like the figures in Group of Dancers and many of the artist’s later works, have been rendered anonymous. By removing the definitive sign of their individuality, Degas has turned his models into representatives of their sex rather than particular idiosyncratic human beings.

Degas, Woman at her Toilette, 1894

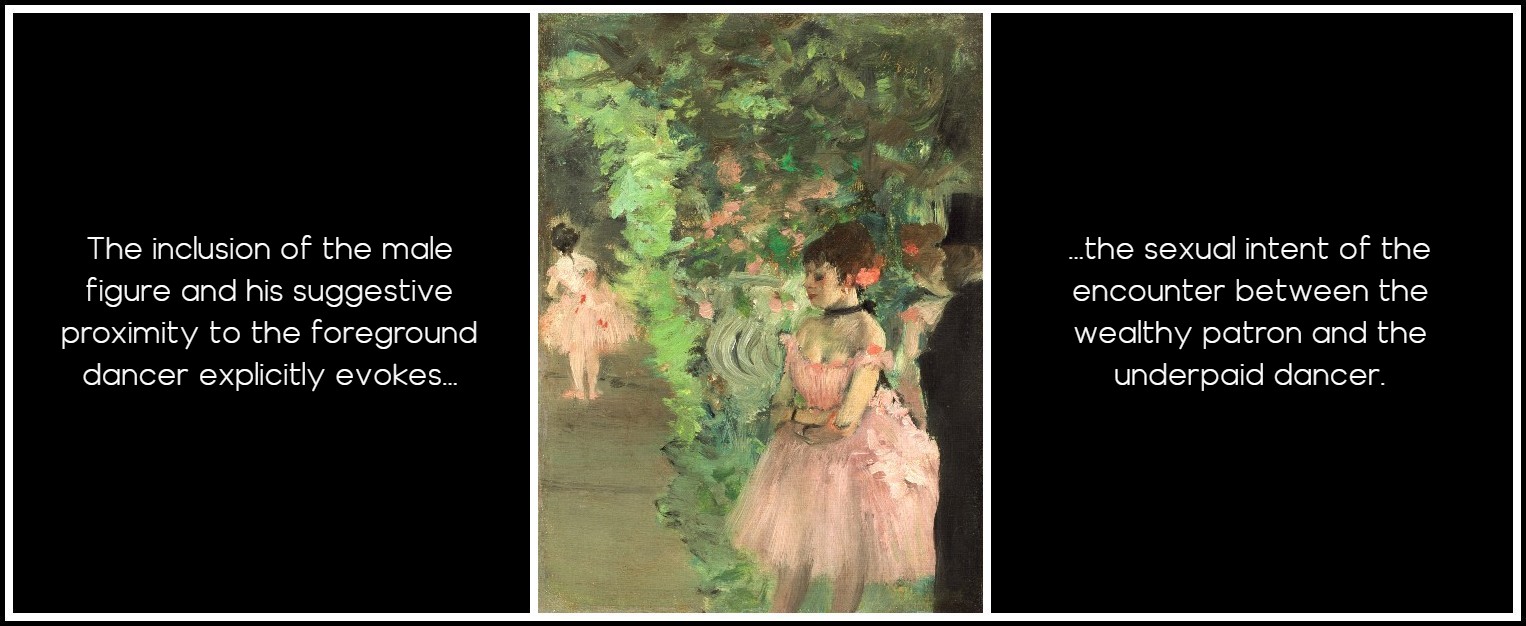

A third picture from Degas’ early years introduces another of his standard female subjects and a further example of his pictorial sign-language at work. Dancers Backstage shows two ballerinas dressed in their finery, standing in the wings at the theatre and waiting for the performance to begin. The delicate pinks of their tutus harmonize with the complementary greens of the scenery, while the soft lighting might suggest a relaxed and innocent moment before the rigours of the dance. Crucial to the meaning of the picture, however, is the dark vertical form at the right-hand edge, a virtual silhouette that can just be identified as a male figure in top-hat and evening dress. This figure would have been instantly recognizable to Degas’ contemporaries as an abonné, or regular subscriber to the theatre, who could go behind the stage and watch the proceedings from the wings, and could also mingle with the dancers before and after performances. It was widely known that such encounters were more sexual than cultural in intention, and that these backstage areas had become a virtual market-place for transactions between wealthy abonnés and underpaid dancers. The inclusion of the male figure in Dancers Backstage and his suggestive proximity to the foreground dancer, explicitly places the scene in such a context. This same dark-suited figure appears frequently in Degas’ ballet pictures of the period, sometimes alone and sometimes in predatory flocks, but its emblematic role as a sexual indicator is never in doubt. In contrast to the colourful and diaphanous dancers, the male figure is often rendered as a black vertical smudge, as if to reduce it to an anonymous and abstract sign of masculinity.

Degas, Dancers Backstage, 1877

The figure of the lurking abonné, with all its connotations of sexual commerce, is conspicuous by its absence in Degas’ later work. Though the subject of dancers posed in the wings remained amongst Degas’ favourites, the dark-suited male spectator effectively disappears after the mid-1880s. A pastel such as The Red Ballet Skirts executed in the late 1890s, is characteristic of many hundreds of such studies, ostensibly showing a moment of respite off-stage during or after a performance. Attention is centred on the figures of the dancers as they lean against the scenery, stretch their tired limbs and adjust their clothing, and on the brilliant colours of their costumes. Not only have the accessories and incidentals of backstage life been excluded but there are no references of any kind to male figures, whether predatory or otherwise. While it can be argued that the furtive male observer is still present in the person of the artist, Degas’ elimination of the abonné figure inevitably redefines the sexual climate of his late work. It has not often been noticed that these works are also free of the male musicians, répétiteurs and sundry theatrical dignitaries who populate such pictures as the early Dance Class.

Degas, Dancers in Red Ballet Skirts, 1900

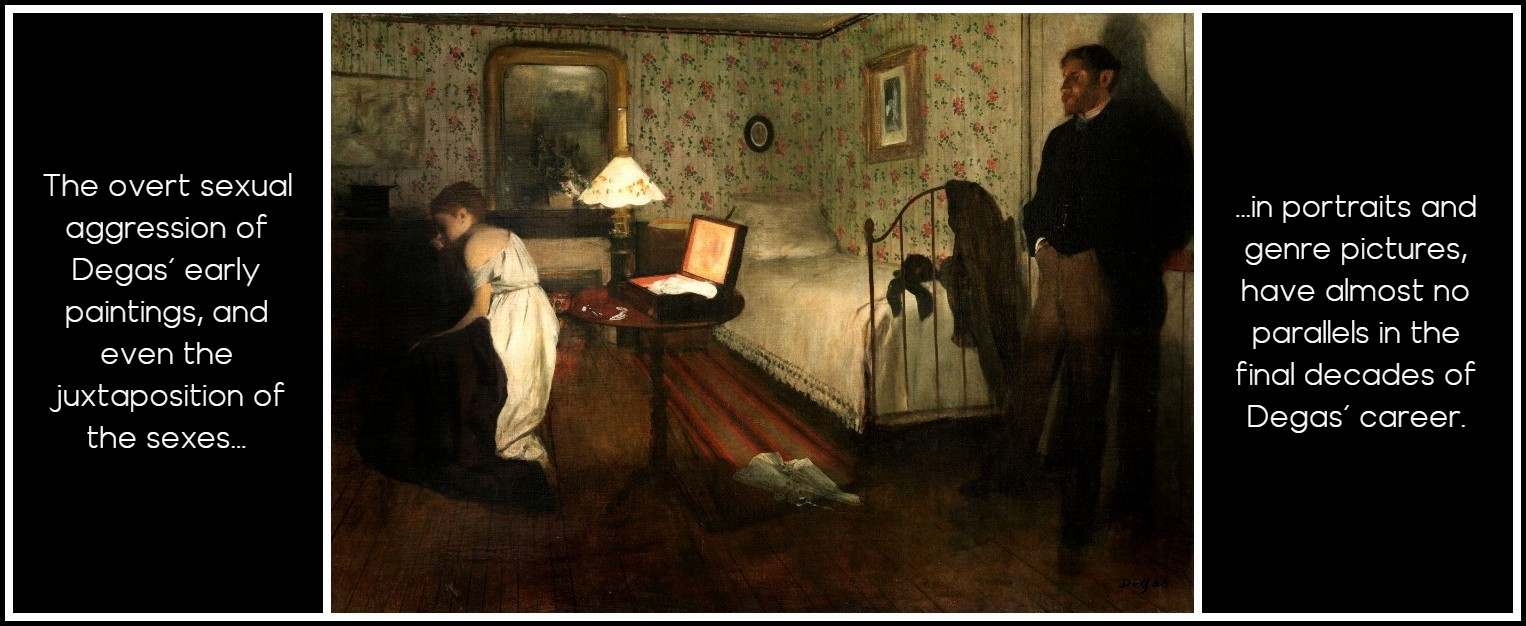

While the significance of the male figures may range from the rapacious to the bland, the artist’s decision to banish them from his pictorial repertoire is part of a wider rejection of images of sexual confrontation and an inclination towards gender-specific subjects. The overt sexual aggression of Degas’ early history paintings, and even the juxtaposition of the sexes in portraits and genre pictures such as Interior, have almost no parallels in the final decades of Degas’ career.

Degas, Interior, 1869

The Red Ballet Skirts may be seen as a vivid summary of many of Degas’ pictorial strategies in his later images of women. The virtual absence of a visible background reduces the specificity of the scene, while the broad handling of the pastel precludes ‘the precise description of facts’ advocated by Zola and Duranty. The faces of the dancers are powerfully modelled, but include few details or evidence of individuality. Throughout the picture, signs of identity, context and narrative have been stripped away, leaving only the figures and costumes of the women and the expressive structure of the composition to animate the subject. A number of commentators have seen such images as a progression towards ‘abstraction’, though the works themselves and the circumstances of their production hardly support such a view. It is known, for example, that amongst his many and varied working practices, Degas continued to pose models for his drawings and sculptures until the last years of his career. While the two principal dancers in The Red Ballet Skirts may both have been based on a single model, each suggests the gravity and particularity of a human figure carefully scrutinized. The muscular shoulders of the foreground dancer and the awkward but finely studied pose of her companion are the product of a continuing dialogue with observed reality. Though the physiognomy of his models is often generalized or concealed, it can be argued that Degas’ responsiveness to the nuances and brute facts of the human body increased with its own advancing age.

Degas, Waiting, 1882

The marked tendency towards the elimination of precise visual indicators in his later work has other consequences for Degas’ images of women. By suppressing the background and reducing the incidental detail of a picture, Degas consistently heightens the role of the figures themselves and draws our attention to the articulation of their bodies, the gestures of their limbs and the colours and textures of hair, skin and fabric. In effect, the depicted female figure is called upon to define its own identity. While this identity may be highly specific as far as physique and deportment are concerned, the woman’s activity is often allowed to remain unclear. There is evidence that this lack of clarity, or even a wilful pursuit of obscurity, became part of Degas’ later artistic programme. In a number of late works, calculated ambiguity results in poses that are tantalizing but inscrutable, proportions and spatial relationships that are contradictory, and even distinctions between subjects that have become blurred.

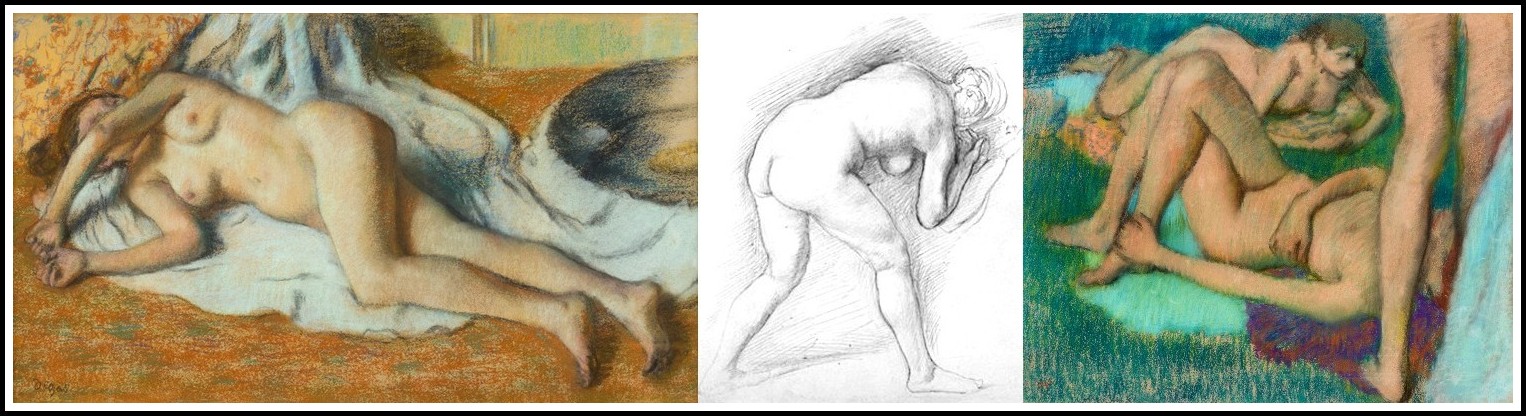

Degas, Baigneuse allongée sur le sol, 1885 | Degas, Femme nue, de dos, penchée en avant, vers la droite, 1865 | Degas, Baigneuses, 1895

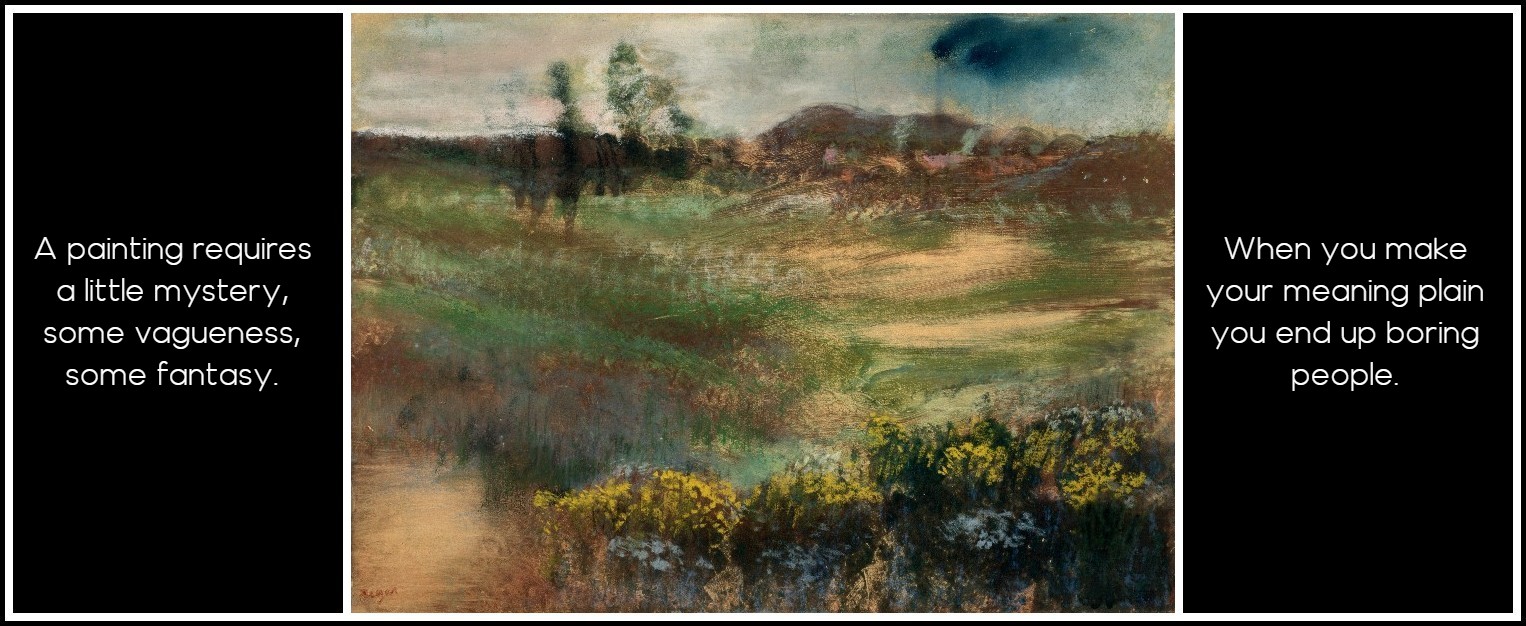

The deliberate construction of ambiguity in much of Degas’ later work may be related to a wide variety of factors, ranging from his changing technical concerns to the shifts in his social and political attitudes. In common with many of his former Impressionist colleagues, Degas had gradually moved away from the documentation of urban life towards an art that was more studio-based, tradition-conscious and self-referential. Socially-specific themes, such as the Milliner’s Shop, the Cafe-Concert, the Circus and the Laundry, were effectively abandoned after the mid-1880s and the subject of the female figure, posed either as a nude or as a dancer, dominated Degas’ later imagery. Along with many artists in their maturity, Degas also evolved a broader, less descriptive handling of line and colour, sometimes dissolving the detail of his pictures in a haze of pastel or oil-paint.1 Degas’ relationship to the Symbolist movement is another little understood aspect of these years, but his recorded admiration for artists such as Gauguin, Redon and Carrière may indicate a shared interest in veiled subject-matter and suggestive form. Most tellingly of all, the artist who had once urged his friend Tissot to join the ‘Salon of Realists’ now openly criticized his own former position. On a number of occasions in later life Degas mocked the naturalism of Zola’s novels and distanced himself from pedantic realism in painting. He told the artist Georges Jeanniot: ‘At the moment, it is fashionable to paint pictures where you can see what time it is, like on a sundial. I don’t like that at all. A painting requires a little mystery, some vagueness, some fantasy. When you always make your meaning perfectly plain you end up by boring people.’

1 – While the documented decline of his eyesight may have contributed to this and other features of the artist’s late work, there has been a tendency to use this explanation inexactly or uncritically.

Degas, Landscape with Smokestacks, 1890

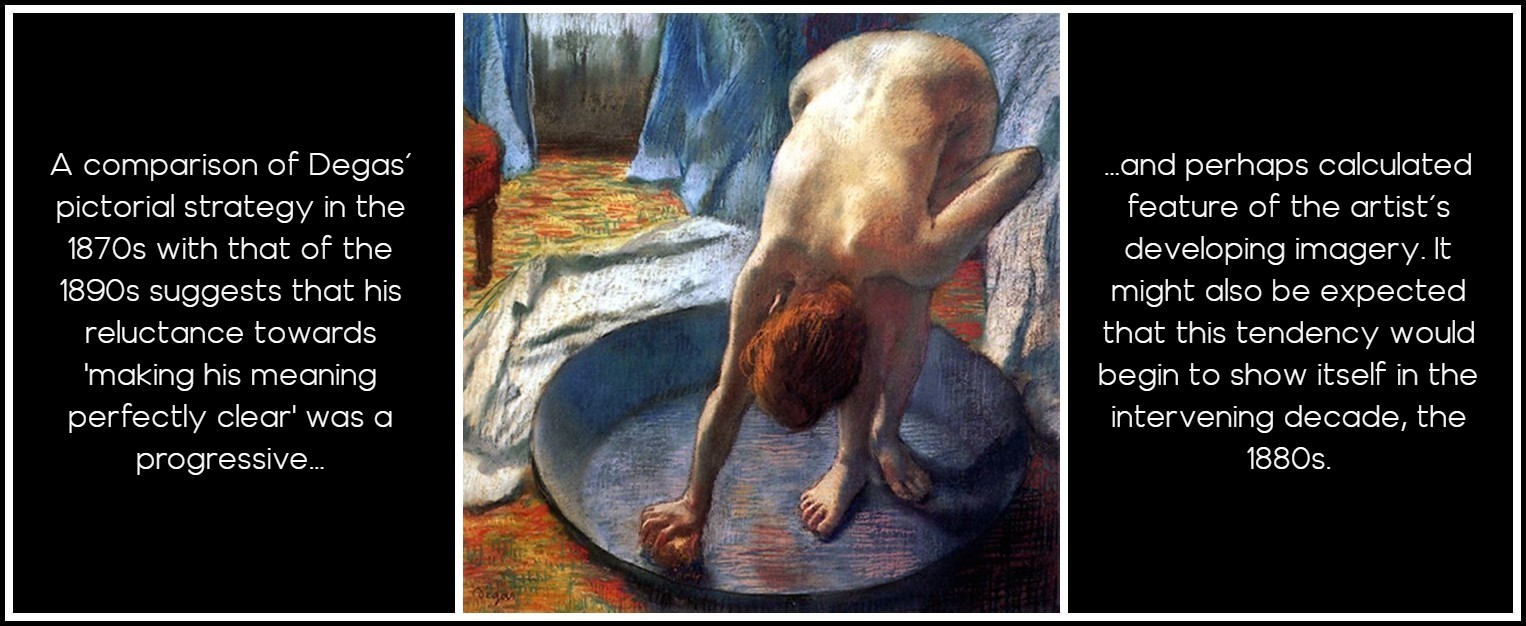

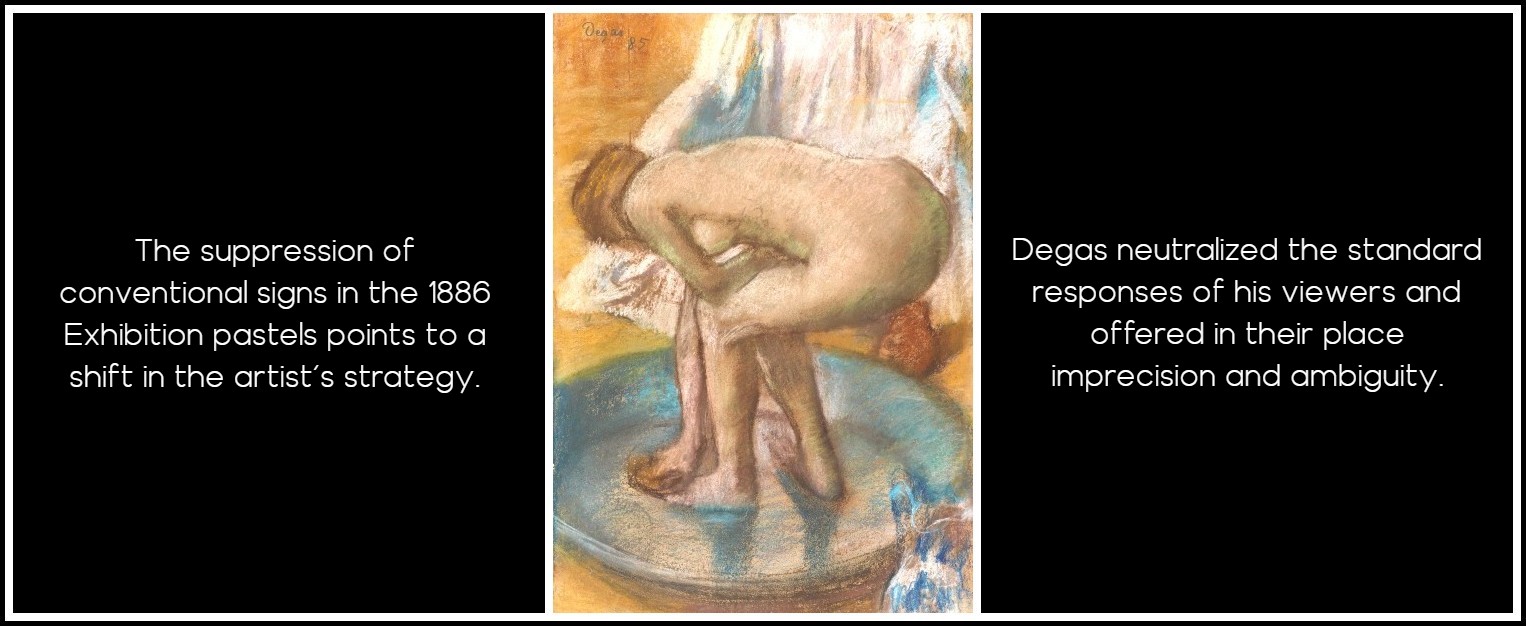

A comparison of Degas’ pictorial strategy in the 1870s with that of the 1890s has suggested that this reluctance towards ‘making his meaning perfectly clear’ was a progressive and perhaps calculated feature of the artist’s developing imagery. It might also be expected that this tendency would begin to show itself in the intervening decade, the 1880s, when Degas’ work passed through a number of transitional phases, perhaps even crises. In this decade, one of the most public manifestations of Degas’ art was the group of pastels of the female nude shown at the final Impressionist Exhibition in 1886. Since their first appearance, these pastels have provoked widespread debate, much of it centred on their subject-matter and the identities of the women depicted. Degas himself listed them in the 1886 catalogue as ‘Women bathing, washing themselves, drying themselves, wiping themselves, combing their hair or having it combed’, but it has subsequently been argued that the artist specifically intended these women to be seen as prostitutes. A number of contemporary critical responses to the pastels have been analyzed, but there have been few attempts to understand the pictures in terms of Degas’ own established visual syntax.

Degas, Woman Bathing in a Tub, 1886

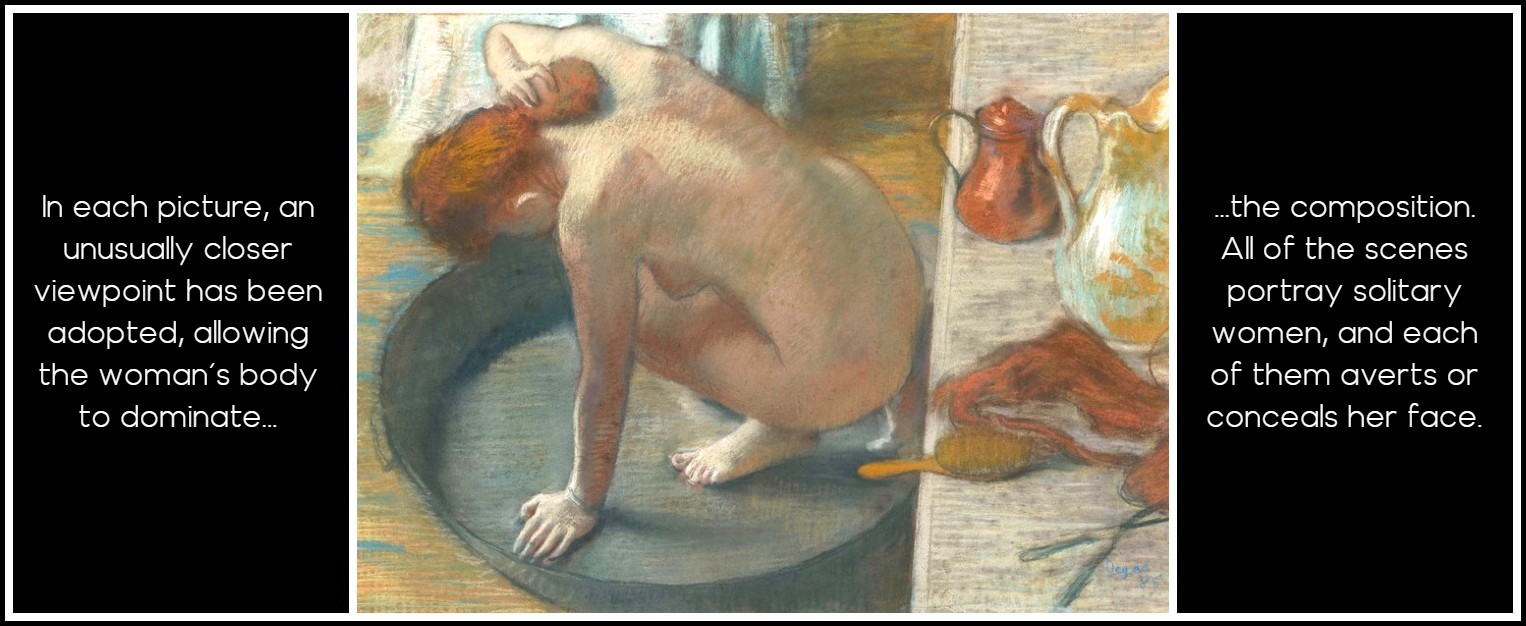

Recent research into the 1886 Impressionist Exhibition pastels has suggested that the pictures in this sequence were among the six or seven originally shown. While there are important differences of size, format and technique within the group of pastels, there are also a number of pictorial strategies that are common to them all. In each picture, an unusually closer viewpoint has been adopted, allowing the woman’s body to dominate the composition and even to project beyond the picture rectangle. The room itself, as a consequence, is largely excluded from our view, and we see little beyond a patch of carpet or an area of wall, with one or two glimpses of furniture or generalized accessories. Though the poses of the women vary remarkably, each of them averts or conceals her face, while their state of undress necessarily excludes some of the standard indicators of class and social identity. All of the scenes portray solitary women and none of them incorporates a reference to another human presence, either male or female.

Degas, The Tub, 1886

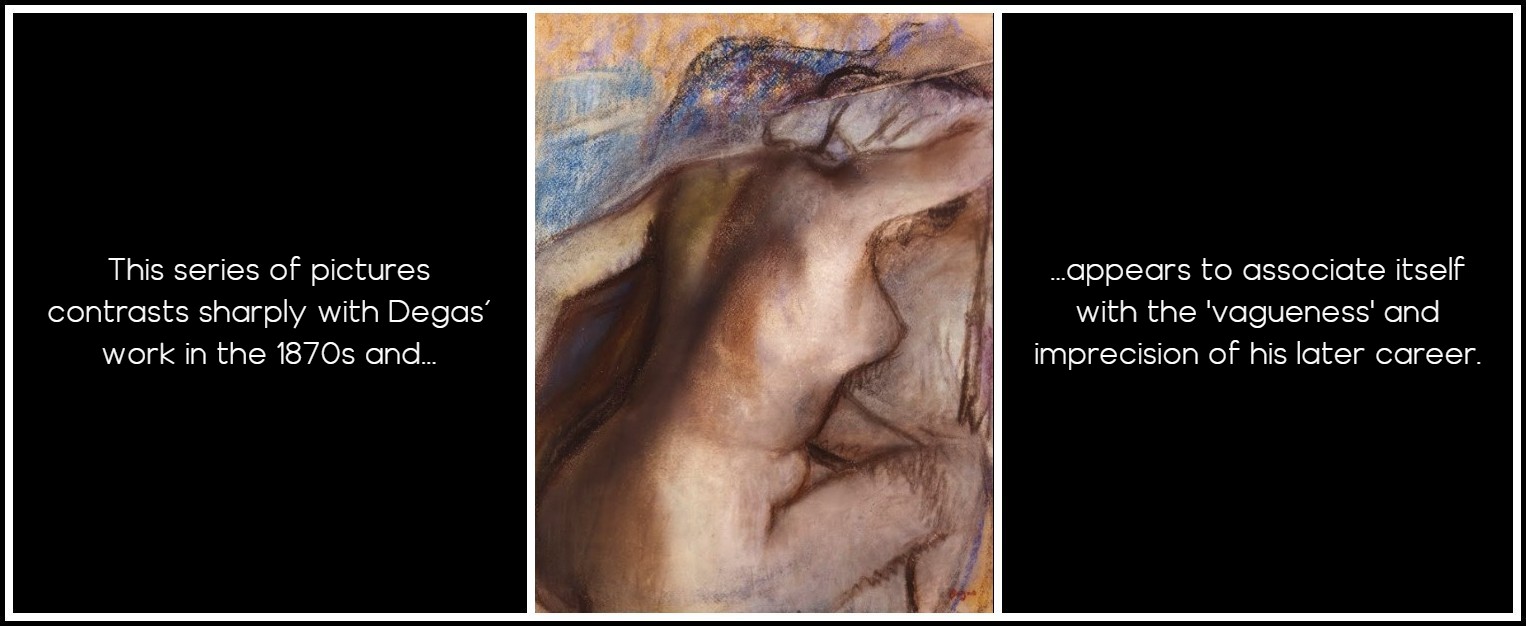

Within the terms that Duranty had laid down a decade earlier, the 1886 pastels are remarkable for their lack of socially specific or pictorially informative detail. After the Bath, for example, excludes the ‘background’ entirely and we are provided with no indication of the woman’s location, status or identity. Other pastels in the group are almost as reticent, offering only ill-defined spaces and a minimal inventory of props and accessories. In this sense, the pictures contrast sharply with Degas’ work in the 1870s and appear to associate themselves with the ‘vagueness’ and imprecision of his later career. This absence of clear and consistent visual indicators has encouraged a wide variety of contradictory readings of the works, not least amongst the critics who first reviewed them in 1886. While one writer found a ‘delicious harmony’ in the pastels, another described them as ‘a distressing poem of the flesh’; some critics remarked on the ‘ugliness’ and the ‘frog-like aspects’ of the women depicted, while Octave Mirbeau found in them ‘the loveliness and power of a gothic statue’; two or three commentators implied that the figures were prostitutes, in contrast to one who identified a model as a ‘fat bourgeoise’, another who saw a ‘ poor working woman, deformed by the toil of modern days’ and a third who decided that they were all ‘decidedly chaste’. As if to summarize their confusion, Maurice Hermel responded to claims that Degas was a misogynist by suggesting that, on the contrary, ‘he is a feminist’.

Degas, After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, 1885

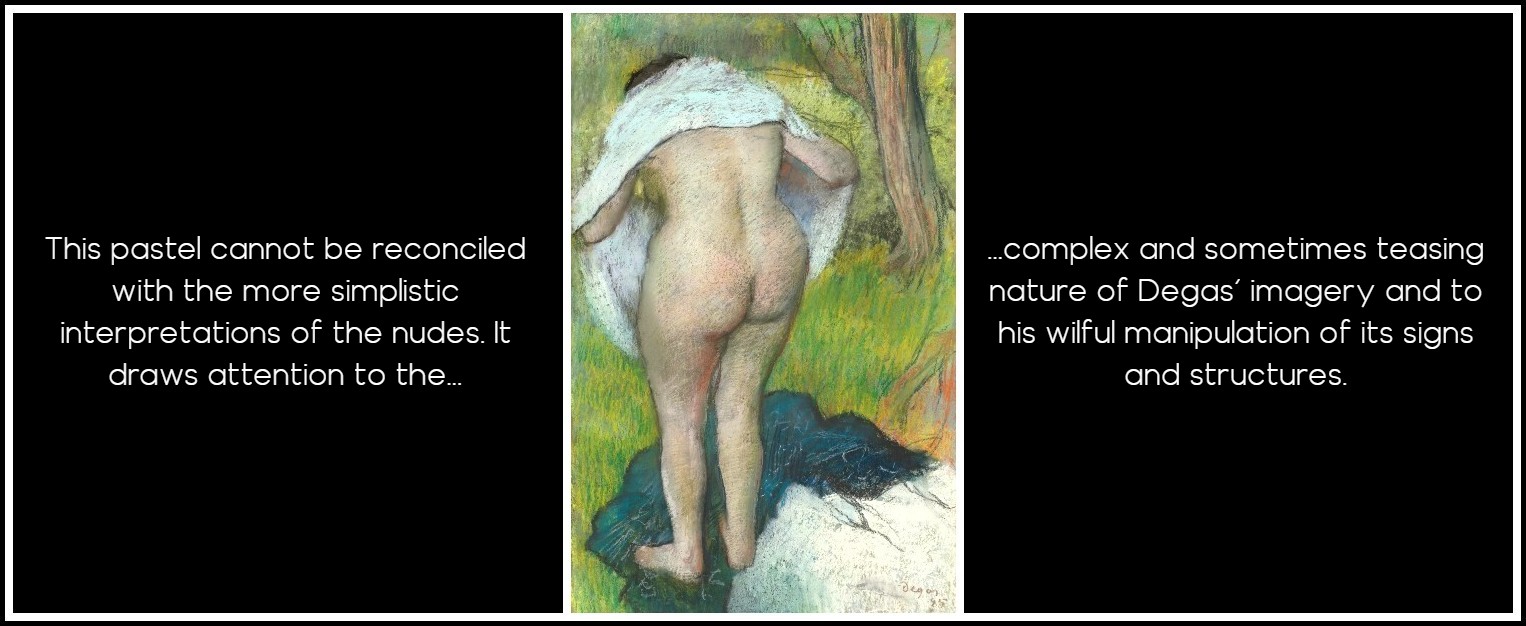

These extraordinary contradictions go well beyond the range of reactions to be expected in such circumstances and point to a fundamental disruption in the process of looking at, and writing about, Degas’ images of women. A number of other features in the critics’ responses are also significant. First, in the absence of informative ‘backgrounds’, the writers were obliged to identify the subject-matter of these pictures largely through a study of the figures themselves. The assumption by some critics that these models belonged to the lower orders tells us a great deal about the confusion of contemporary class attitudes, but raises as many questions as it answers. Secondly, the exhibited pastel which most explicitly refuted the identification with prostitution was (and has remained) the least discussed by Degas’ critics. In Young Woman Dressing Herself, the model is posed against grass and trees, in a rural setting at the opposite extreme to the ‘ambiguous bedrooms’ mentioned by one of the 1886 critics. This pastel cannot be reconciled with the more simplistic interpretations of the nudes and has, perhaps, been overlooked for that reason. It also draws attention to the complex and sometimes teasing nature of Degas’ imagery and to his wilful manipulation of its signs and structures. By introducing a tree trunk, which is little more than a city-dweller’s hieroglyph for the countryside, Degas transformed the possible readings of this picture; similarly, by excluding all such devices, the artist could opt for the unmapped and uncertain pictorial territory that has so confounded his critics.

Degas, Baigneuse s’essuyant [Woman Drying Herself], 1885

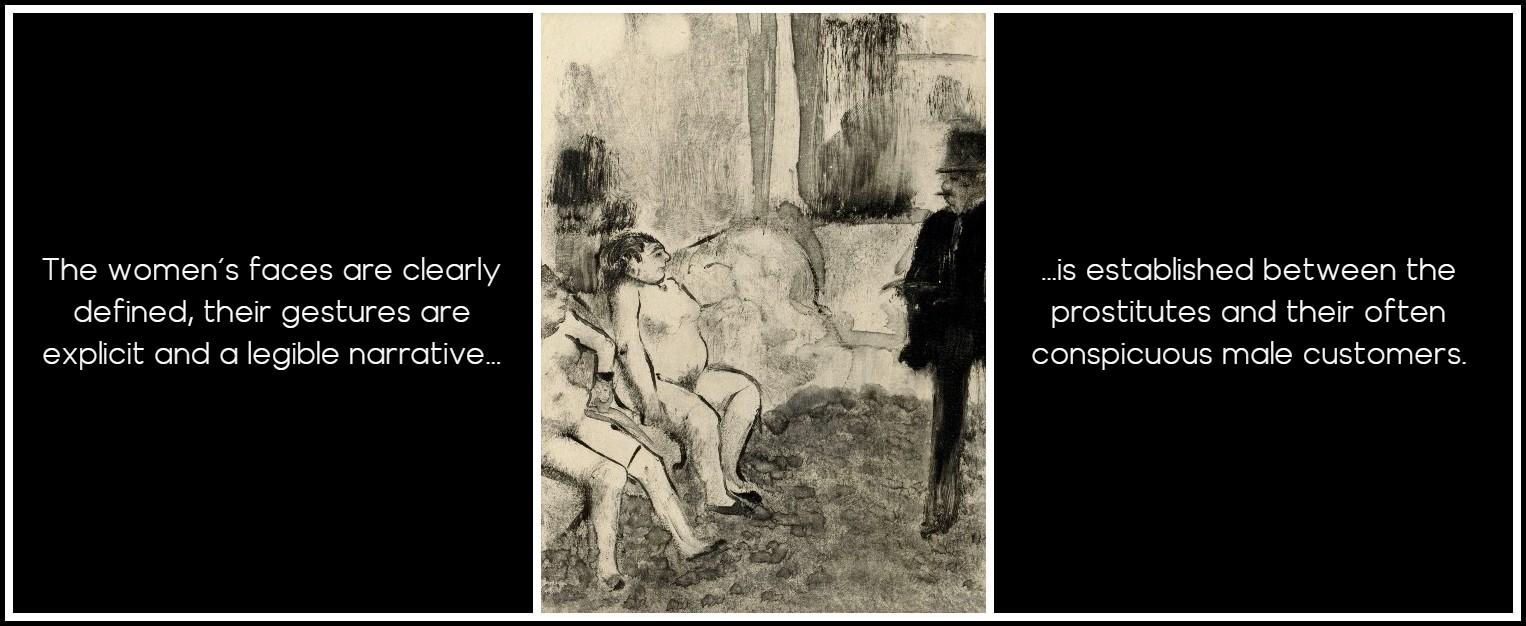

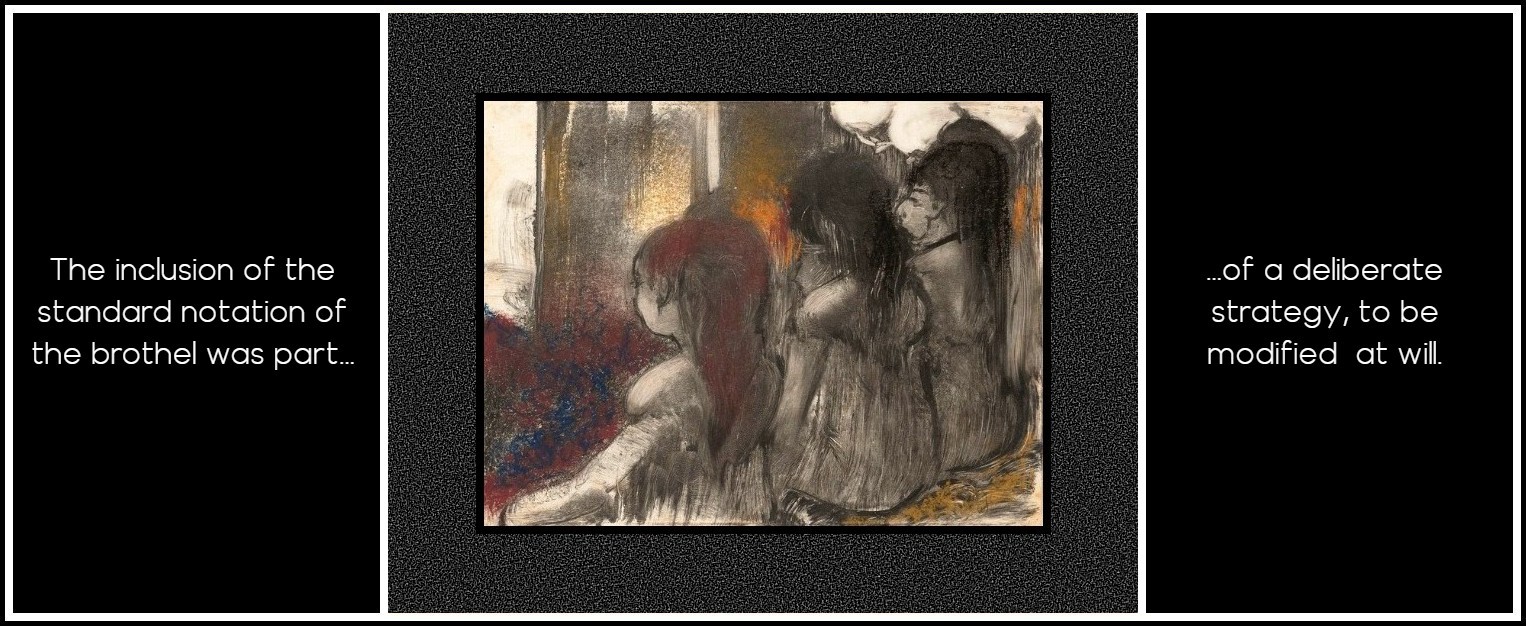

It has been argued recently that the 1886 pastels were the outcome of an evolution in Degas’ work that began with the monotypes of the late 1870s. Technically, thematically and visually, the pastels developed certain features of these prints, while emphatically rejecting others. The monotypes include specific scenes of brothel life and studies of individual prostitutes, most of them represented in the kind of descriptive detail that characterized Degas’ work in this earlier decade.

Degas, Three Women in a Brothel, 1877

In these scenes, the women’s faces are clearly defined, their gestures are explicit and a legible narrative is established between the prostitutes and their often conspicuous male customers. Even on the small scale of the monotype, the mirrors, gas-lights and banquettes of the salle d’attente, and the more modest furnishings of the bedrooms, are clearly described, while the prostitutes are identified by their striped stockings, elaborate coiffures and scanty negligées.

Degas, The Client, 1879

In this context, Degas was evidently content to use the standard notation of the brothel, and to define the identities of his characters and the nature of their commerce. While these monotypes refer to a specific category of brothel and were intended for a selective and private audience, it is clear that the inclusion of such conventional signs was part of a deliberate strategy, to be modified or manipulated at will.

Degas, Trois filles assises, de dos, 1879

By the same token, the suppression of these conventional signs in a later group of monotypes, and their omission from the 1886 pastels, points to a shift in the artist’s strategy. In rejecting the stereotypical signs and structures of prostitution, Degas neutralized the standard responses of his audience and offered in their place imprecision and ambiguity. In this sense, the panic of Degas’ contemporaries and the confusion of later generations have been the controlled outcome of his pictorial manoeuvering. The critic who discovered a ‘fat bourgeoise’ was neither nearer or further from the image than the one who saw the ‘streetwalker’s pasty flesh.’; both of these allusions, as well as those to ‘a young cat’ or even ‘a kneeling Venus’, are made possible and perhaps encouraged by the 1886 pastels, while none of them is allowed to become definitive.

Degas, Woman Bathing in a Shallow Tub, 1885

It is this capacity for the knowing manipulation of visual language, and for the modification of that language in the context of differing subject-matter, that has so often been overlooked and misunderstood in the study of Degas’ female imagery. The orchestration of spaces, settings and physiognomy was often calculated for specific ends, just as the suppression or elimination of these factors might be preferred in other circumstances. As writers like Duranty understood well, the character of an image could be established both by inclusion and by exclusion, by radical intervention or by the subtlest of visual inflections. In his earlier female subjects, Degas’ commitment to social documentation was reflected in a number of pictorial devices that accentuate detail, identity and social behaviour. In the 1880s, his pictures began to be less descriptive and more broadly executed, often using pastel to create an image that was both dense and richly allusive. During the last decades of his career, Degas virtually eliminated the deep spaces, ‘backgrounds’ and tokens of direct sexual confrontation found in his earlier work, actively promoting the dislocation and ambiguity of his subject-matter. These late drawings, pastels and paintings of women are, by intention and design, highly resistant to description and it is no coincidence that they remain amongst the least discussed of Degas’ works. By confronting these pictures, however, and by considering them alongside Degas’ earlier and more celebrated female imagery, it is possible to identify some of the patterns and significances within his visual syntax. While none of these patterns is unproblematic and while all of them have their inconsistencies, together they offer the possibility of a more informed and particularized, if perhaps less convenient, characterization of Degas’ images of women.

Degas, After the Bath, 1898 | Degas, Woman Drying Herself, 1899

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments