I. INTRODUCTION | II. CONTEMPORARY ART IN CONTEXT | III. BRIEF PHILOSOPHICAL REFLECTION | IV. DIGNITY OF THE HAND | V. MATERIALITY OF PAINT | VI. AURA OF THE INDIVIDUAL | VII. CONCLUSION | VIII: CODA

THE JOY OF PAINTING

TOMMASO FATTOVICH

THE DEFIANCE OF CONTEMPORARY ART

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

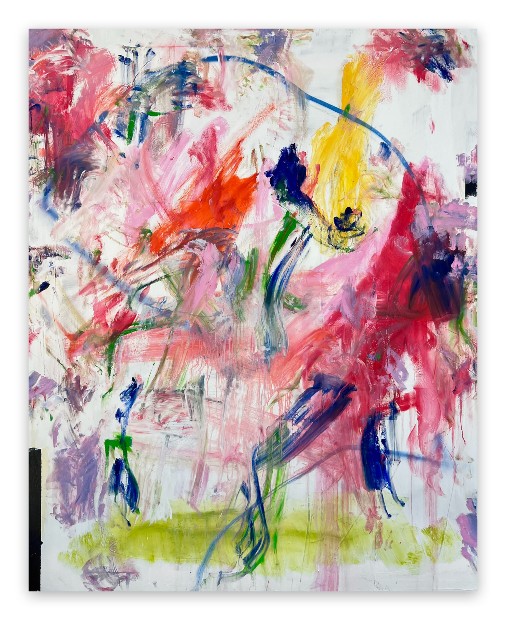

Tommaso Fattovich, Shoots and Ladders, 2023

I. INTRODUCTION

The ‘joy of painting’ may not excite you like the ‘joy of sex’; nevertheless, dear reader, my aim in this essay is to demonstrate that in Tommaso Fattovich’s work the joy of painting, amply evident, is a source of real excitement. Yes, via a set of reflections that situate Fattovich in a defiant relation to contemporary art, I will endeavour to show how his paintings can restore to our fragmented lives a sense of wholeness, however fleeting. A bold claim, I admit, but one which I will rigorously support. How? First, I will zoom out to examine the contemporary art context in which visual artists work today (part 2). Next, I will zoom out further to offer a philosophical reflection on art (part 3). I will then zoom in to focus on Fattovich’s paintings and artistic practice (parts 4, 5, 6). Finally, I will offer a brief conclusion (part 7) and a coda (Part 8). My thesis can be stated simply: Fattovich paints in a way that places his work beyond the reach of the long shadow of conceptualism, a shadow cast by contemporary art visible even in painting today. My argument will be structured in concentric ‘spirals’, centered, successively, on three themes: the dignity of the hand, the materiality of paint, and the aura of the individual. You may find too grand the case I make for Fattovich’s paintings: I hope to win you around to it through an analysis that only you can validate by your viewing of the work. What Fattovich’s art offers, if not the joy of sex, is the joy of painting: the high of wholeness, the turn-on of authenticity, the thrill of being-in-the-moment. The aim of this essay is simply to ‘clear the path’ as you make your way towards the work.

Tommaso Fattovich, Waves, 2023

II. CONTEMPORARY ART IN CONTEXT

A. WHAT IS CONTEMPORARY ART?

For decades discussions of contemporary art have degenerated into sterile quarrels, generating more heat than light. Defining the term more rigorously than is customary offers a way out of this impasse. To this end, French sociologist Nathalie Heinich proposes to consider contemporary art as a distinct artistic genre and a new paradigm of art.1 In her schema, contemporary art is not considered chronologically, as a certain period in art history, but as a generic category, defined by a specific practice of art. So, if classical art is a genre that implements the academic canons of figurative representation, more or less idealized, and if modern art is a genre that challenges the rules of figuration and demands the expression of the artist’s subjectivity, then contemporary art is a genre that plays on the ontological borders of art, challenging the very notion of a work of art as it is commonly understood. While recognition of a plurality of genres (and consequently of a plurality of principles of appreciation) has the advantage of defusing the explosive confrontations between the advocates and adversaries of contemporary art, the generic approach, because it is largely limited to the aesthetic dimension, fails to adequately capture, Heinich argues, the status of contemporary art. Indeed, she asserts, the specificity of contemporary art is apparent at many levels other than that of the works themselves. More than a genre, then, contemporary art is a new artistic paradigm.

1 – Nathalie Heinich, Le paradigme de l’art contemporain : Structures d’une révolution artistique (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2014) ; Le Triple jeu de l’art contemporain (Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1998) ; Pour en finir avec la querelle de l’art contemporain (Paris: L’Échoppe, 1999). In English, Martha Buskirk in her book The Contingent Object of Contemporary Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005) covers much the same ground as Nathalie Heinrich.

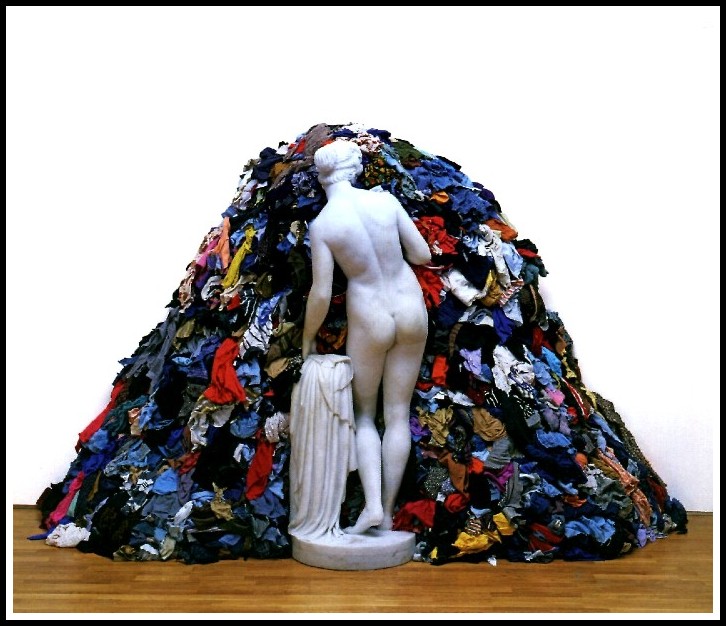

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venus of the Rags, 1967

Nathalie Heinich explains that, as an unconscious model that formats the sense of what is normal in art, an artistic paradigm1 is operative not only in the creation but also in the perception of artworks. Contemporary art, insofar as it entails a redefinition of art, represents a radical paradigm shift in Western art. Indeed, its ontological rupturing of the borders of the generally accepted understanding of art has, as Kuhn’s theory posits, relegated perennial artistic problems—to do, for example, with easel painting and pedestal-mounted sculpture—to a small band of ‘rearguard’ artists, while bringing to the fore previously peripheral problems such as the limits of what can be accepted as an ‘artistic proposition’. Where classicism and modernism offered beauty and aesthetic emotion, contemporary art offers sensation. Where the earlier paradigms valued closeness and authenticity, the current one swears by distance and irony. The new paradigm radicalizes the ‘regime of singularity’, favoring novelty and originality, while the ‘regime of community’, with its attention to traditions and standards, reigned in the old paradigms.

1 – Cf. Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (University of Chicago Press, 1962)

Cristina Iglesias, Pavilion Suspended in a Room I, 2005

Viewers enter the structure and piece together letters to form a text

In this new paradigm, as Nathalie Heinich explains, the four types of contemporary art—the readymade, conceptual, performance, and installation art—share many of the following traits.

1. The work of art does not reside in the object the artist proposes. Why? Either because there is no object, or because the object has no value or even existence without the textual discourse that accompanies it.

2. The ‘artistic proposition’ is dematerialized and formless, consisting, for example, in light, air, or a simple conversation.

3. Ideas are considered works of art and proclaimed as such by the artists. The object is but a pretext for the idea.

4. ‘Fake’ and ‘authentic’ become meaningless terms to the extent that the work is no longer linked to its origin.

5. Hybridity: The art in an assemblage of material elements such as one finds in an installation, for example, lies in their selection, juxtaposition, and the context in which they are placed.

6. Ephemeralization: The artist’s body, for example, is the only object; the work resides in the experience of the body performing before a participating (even if only passively) audience.

7. Documentation: The documentation associated with the work is at least as important, if not more so, than the work itself. This applies to both ephemeral and conceptual art.

8. Attitude: The artist’s attitude replaces the art object. Attitude can only exist as a work of art in an institutional framework that provides it with a full set of mediations.

Finally, Nathalie Heinich points out that today the contemporary art paradigm has won the resolute adherence of art specialists and state institutions, as well as of the most influential market players and the richest and most educated members of the public.

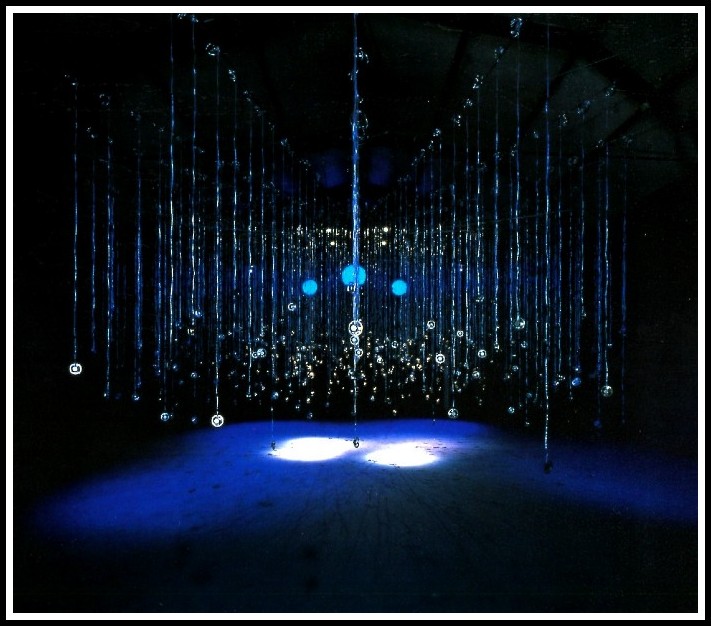

Susan Hiller, Witness, 2000

Suspended loudspeakers play eyewitness accounts of UFO sightings

B. THE AESTHETICIZATION OF THE WORLD: THE SOCIETAL CONTEXT IN WHICH ART OPERATES NOW

After the ages of art-for-the-gods, art-for-the-princes, and art-for-art’s sake, we are now in the age of art-for-the-market, asserts French essayist Gilles Lipovetsky.1

1. At the very moment when contemporary art is ‘de-defining’ art, daily life is being ‘artified’.

2. Businesses have generalized aesthetic strategies in order to get their hands deeper into consumers’ pockets.

3. Design is everywhere. It differentiates not only hotels, restaurants and urban scenes, for example, but the least everyday objects too.

4. Everybody is an artist: gardeners, barbers, cooks; business people, professors, crooks.

5. Everything is art: one’s lifestyle, for example, one’s body, one’s outlook on the world.

6. Individuals construct their identity via the aesthetic dimension of their consumer choices.

7. Consumers meet the aestheticization of the economic sphere with the aestheticization of their ego ideal. Living and sacrificing oneself for principles or other people is out; inventing oneself, establishing one’s own rules in the quest for a beautiful life, is in.

1 – Gilles Lipovetsky & Jean Serroy, L’esthétisation du monde : Vivre à l’âge du capitalisme artiste (Paris : Éditions Gallimard, 2013). Freely translated here by Richard Jonathan.

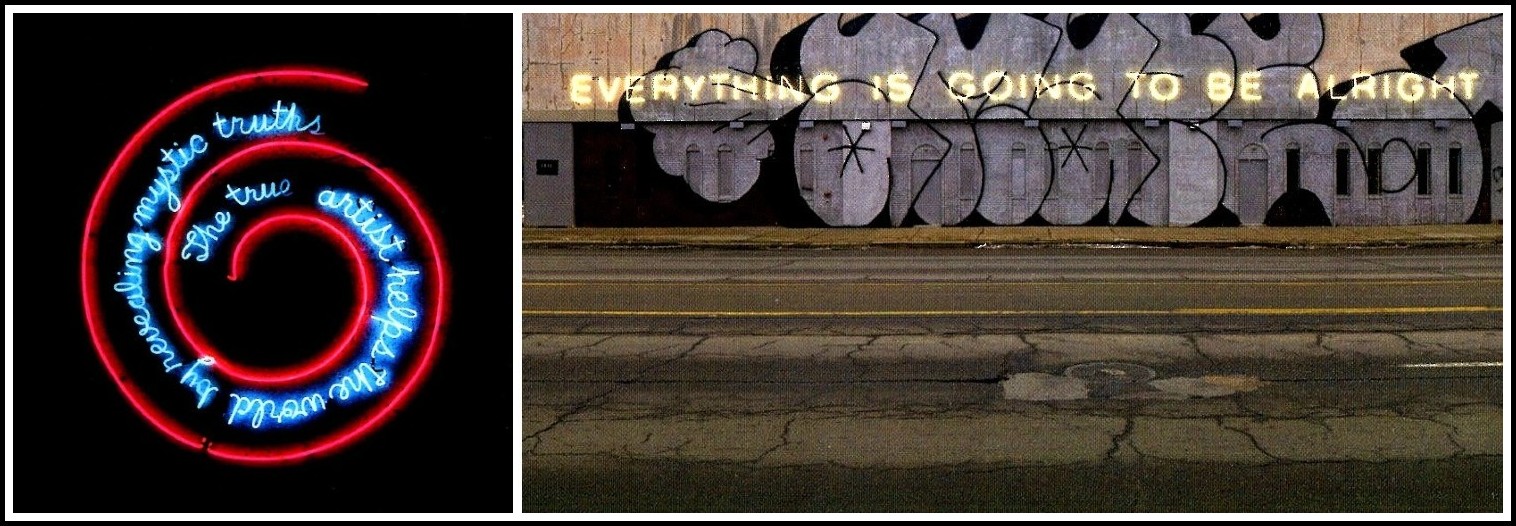

Bruce Nauman, The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths, 1967 | Martin Creed, Everything is Going to Be Alright, 2007

C. FOUR CONTEMPORARY ART REALITIES

1: CONTEMPORARY ART GALLERIES

Traditionally, the model for dealers has been to bet on raw talents, and support these artists until work by some of them sells well enough to cover the bets made on all the others. Under the mega-gallery model that Gagosian pioneered, the top dealers don’t even bother with nascent artists. Ellie Rines, who runs 56 Henry, a small gallery on the Lower East Side, told me, ‘What I can do that the big galleries can’t is that I spot someone who has potential’. Gagosian is content to let people like Rines do the wildcatting. Once they’ve discovered an unknown and nurtured her into a valuable commodity, he can lure the artist away with promises of more money, more support, and a bigger platform. Patrick Radden Keefe, The New Yorker, 24 July 2023

The polarization between big international galleries and small local ones is intensifying. Mid-market galleries are being squeezed, with some closing down and others changing their business model. Georgina Adam, Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the Twenty-First Century (London: Lund Humphries, 2017)

Larry Gagosian, with nineteen galleries that bear his name, from New York to London to Athens to Hong Kong, generating more than a billion dollars in annual revenue, may well be the biggest art dealer in the history of the world. He represents more than a hundred artists, living and dead, including many of the most celebrated and lucrative. All told, Gagosian has more exhibition space than most museums. In 2012, he opened a gallery on the grounds of Le Bourget airport, outside Paris, where his clients can buy art upon landing in their private jets. Patrick Radden Keefe, The New Yorker, 24 July 2023

Good Mother Gallery, Los Angeles | Underdogs Gallery, Lisbon | Perrotin Gallery New York | Nino Mier Gallery 3, Los Angeles

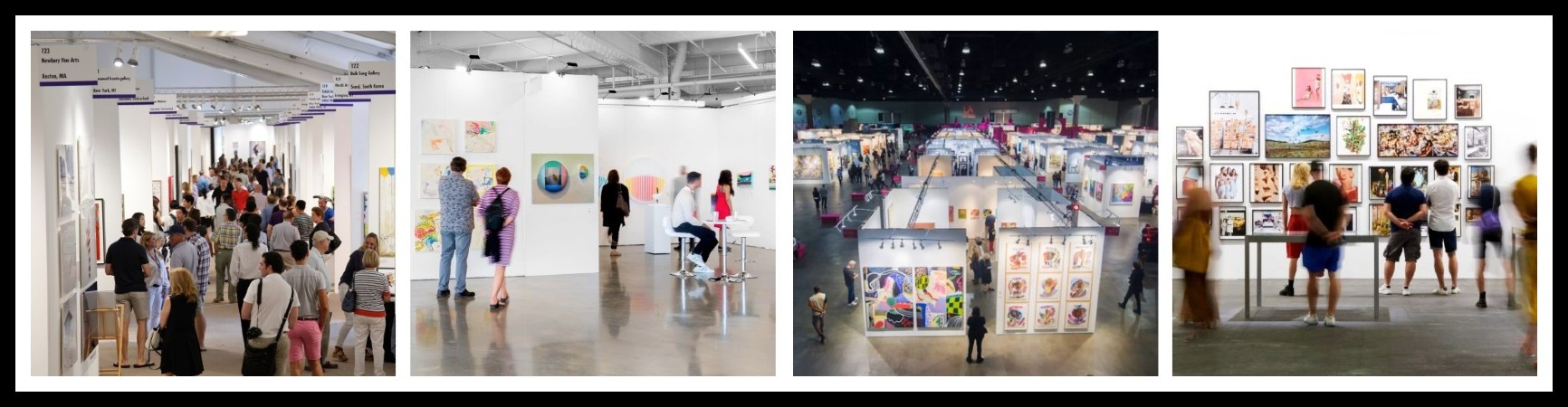

2: CONTEMPORARY ART FAIRS

Art fairs grew at breakneck speed from the turn of the millennium and reached unmanageable levels in the years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. With each success came increased dominance and the industry seemed out of touch with the galleries it purported to support. Art fairs were expensive exercises. For dealers with art priced at the lower end of the spectrum, it all stopped adding up. Melanie Gerlis, The Art Fair Story: A Rollercoaster Ride (London: Lund Humphries, 2021)

Where collectors were previously viewed as clients of the galleries, increasingly they had become clients of the fairs. The relationship had shifted. Other factors leading to the shifting loyalties include the sheer number of galleries that exist now and the shorthand that has evolved in determining where a gallery stands in the overall pecking order based on which fairs they do and where their booth is located in them. The fair has become the brand that collectors trust, the brand that sells the art, displacing the gallery to a large degree. The power that the fairs have over a gallery’s financial well-being has become starkly obvious. Viewing the fair as ‘the brand they trust’ makes collectors less reliant—in the middle and emerging sectors of the market—on developing a personal relationship with the dealers they meet there. Edward Winkleman, Selling Contemporary Art: How to Navigate the Evolving Market (New York: Allworth Press–Skyhorse Publishing, 2015)

Artists prefer having their work presented in a gallery context over an art fair. The top metric for the ‘success’ of any artwork at fairs is whether it sold or not. Having artwork not sell at a fair puts stress on the artist’s relationship with the dealer and risks influencing what the artist decides to create moving forward. Edward Winkleman, op. cit.

Hamptons Fine Art Fair | Plural Contemporary Art Fair Montreal | Los Angeles Art Fair | Art Basel

3: CONTEMPORARY ABSTRACTION: THE MEDIOCRITY OF ART-SCHOOL PAINTING

Jerry Saltz

Jerry Saltz, ‘Zombies on the Walls: Why Does So Much New Abstraction Look the Same?

In Jerry Saltz, Art is Life: Icons & Iconoclasts, Visionaries & Vigilantes, & Flashes of Hope in the Night

(UK: Octopus Publishing, 2022; article originally published in 2014) pp. 135-138

In today’s greatly expanded art world—and art market—it’s the artists making diluted art who have the upper hand. A large swath of the art being made today is driven by the market, and specifically by not very sophisticated speculator-collectors who prey on their wealthy friends and their friends’ wealthy friends, getting them to buy the same look-alike art. Galleries everywhere are awash in these brand-name reductivist canvases, all more or less handsome, harmless, supposedly metacritical, and just ‘new’ or ‘dangerous-looking’ enough not to violate anyone’s sense of what ‘new’ or ‘dangerous’ really is. All of it is impersonal, mimicking a set of preapproved influences. It’s also a global presence.

This work is decorator-friendly, especially in a contemporary apartment or house. It feels ‘cerebral’ and looks hip in ways that flatter collectors, even as it offers no insight into anything at all. It’s all done in haggard shades of pale, deployed in uninventive arrangements that ape digital media, or something homespun or dilapidated. Replete with self-conscious comments on art, recycling, sustainability, appropriation, processes of abstraction, or nature, this array of painting styles shares a common vocabulary of smudges, stains, spray paint, flecks, spills, splotches, almost-monochromatic fields, silk-screening, or stenciling. It is visual Muzak, blending in. Collectors needn’t see shows of this work, since it offers so little visual or material resistance.

Almost everyone who paints like this has come through art school. Thus the work harks back to the period these artists were taught to lionize: the supposedly purer days of the sixties and seventies, when their teachers’ views were being formed. The saddest part of this trend is that even better artists who paint this way are getting lost in the onslaught of copycat mediocrity and mechanical art. Going to galleries is becoming less like venturing into individual arks, and more like going to chain stores where everything looks distantly familiar.

Art School

4: THE BIG GUYS: TASTE, COMMODIFICATION, & CORPORATIZATION IN CONTEMPORARY ART

The art market is a ‘winner-takes-all’ market.1 In 2017, just 25 artists account for nearly 50% of global auction revenue from contemporary art. J. Halperin & E. Kinsella, ‘The “Winner Takes All” Art Market’, 20 Sep 2017 (Artnet).

Gagosian says he prefers collectors who trust their own taste. But it has long been suggested that many of his collectors simply ape his taste. In 1984, the cantankerous art critic Robert Hughes bemoaned the new generation of collectors: ‘Most of the time, they buy what other people buy. They move in great schools, like bluefish, all identical.’ Indeed, many prominent collections now reflect the sensibility of Gagosian. Patrick Radden Keefe, The New Yorker, 24 July 2023

Robert Scull was a rainmaker. People that respected him decided that if he liked something, it was worth liking. We’re lemmings! In the art world there’s a lot of followers; a few leaders and a lot of followers. Which is okay if you follow the right leader. Collector Stefan Edlis, The Price of Everything, dir. Nathaniel Kahn, HBO DVD 2018

Some major collectors now buy and sell art so frequently, and in such enormous quantity, that little of it gets displayed at all. The Geneva Freeport—a tax-free zone in Switzerland where art is stored in climate-controlled, highly secure facilities—is thought to contain more than fifty billion dollars’ worth of art and antiquities, including works by van Gogh, Picasso, and Leonardo da Vinci. It would be one of the biggest museums in the world if it were open to the public. More and more art disappears into loading bays in Switzerland. One perverse outcome of the hysterical inflation of art prices in the past half century is that great works end up reduced to stock lists. Patrick Radden Keefe, The New Yorker, 24 July 2023

1 – For an excellent scientific explanation of how the winner-takes-all-market in art works, see the section, ‘How Collectors Influence the Global Art Market’ by Alessia Zorloni & Antonella Ardizzone in Art Wealth Management: Managing Private Art Collections, ed. Alessia Zorloni (Springer International, 2016) pp. 69-71.

Depiction of an Art Trading Center | Portrait of a Contemporary Artist | Depiction of a Collector

III. A BRIEF PHILOSOPHICAL REFLECTION ON ART

B. — I speak of an art turning from the plane of the feasible in disgust, weary of its puny exploits, weary of pretending to be able, of being able, of doing a little better the same old thing, of going a little further along a dreary road.

D. — And preferring what?

B. — The expression that there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express.

To be an artist is to fail, as no other dare fail, that failure is his world and the shrink from it desertion, art and craft, good housekeeping, living. All that is required now is to make of this submission, this admission, this fidelity to failure, a new occasion, a new term of relation, and of the act which, unable to act, obliged to act, he makes, an expressive act, even if only of itself, of its impossibility, of its obligation.

I trust, dear reader, you’ve recognized the voice of he who wrote Waiting for Godot. Yes, he who also wrote: ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’1 If I’ve chosen to open this reflection on art with these words of Samuel Beckett,2 it is because discourse on ‘the re-enchantment of the world through art’3 is often trite and I, for my part, wish to oppose that triteness by taking a different tack.4

1 – Samuel Beckett, ‘Worstward Ho’, in Nohow On, Company, Ill Seen Ill Said, Worstward Ho (New York: Grove Press, 1996) p. 89

2 – The first two citations are from ‘Three Dialogues with George Duthuit’, first published in Transition in 1949; reprinted in Samuel Beckett, Disjecta, ed. Ruby Cohn (New York: Grove Press, 1984) pages 139 & 145.

3 – This notion will run, implicitly, throughout my discussion of Tommaso Fattovich’s paintings, below.

4 – Triteness is ripe in the art world. Just listen to the interviewees in Nathaniel Kahn’s art world documentary, The Price of Everything,* for example: the mediocrity of the discourse, the glibness with which inanities are uttered, bears out the truth of this observation.

* The Price of Everything, dir. Nathaniel Kahn, HBO DVD 2018

John Minihan, Samuel Beckett, 1985

The Hermitage didn’t stop the Holodomor, Angkor Wat didn’t stop the Khmer Rouge, Mozart didn’t stop Mauthausen. So let us be humble. Let us be content with art as an encounter between a work and an individual. Let it suffice that the astonishment that may arise from that encounter make, however momentarily, one less zombie seeking distraction before sinking into the big sleep.

When wind and hawk encounter,

What remains to keep?

So you and I encounter,

Then turn, then fall to sleep.1

So wrote Leonard Cohen in ‘As the Mist Leaves No Scar’.

True love leaves no traces

If you and I are one

It’s lost in our embraces

Like stars against the sun2

So he wrote in the song version of the poem. Do you see what I’m getting at, dear reader? Do you see that art has to do with being, not having? ‘Only art lets be’, wrote Martin Heidegger, ‘in unconcealment dwells hiddenness and safekeeping’.3 Reader, put that in your pipe and smoke it.

1 – Leonard Cohen, ‘As the Mist Leaves No Scar,’ The Spice-Box of Earth, 1961. Also in Leonard Cohen, Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs (New York: Vintage Books, 1994) p. 15

2 – Leonard Cohen, ‘True Love Leaves No Traces’, Death of a Ladies’ Man (Warner Bros. Records, 1977). Also in Leonard Cohen, Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs (New York: Vintage Books, 1994) p. 216

3 – Quoted in George Steiner, Heidegger, Second edition (New York: Fontana Press, 1992) pp. 133-34

As the Mist Leaves No Scar | 1963, Leonard Cohen & Marianne Ihlen, 1965 | True Love Leaves No Traces

Lois Oppenheim: Beckett’s phenomenology of painting bears a resemblance to Heidegger’s. Both in form and content his metacritical essays on painting are highly reminiscent of ‘The Origin of the Work of Art,’ where the art ‘object’ is similarly located outside the aesthetic domain—in the totalizing movement of the concealment and disclosure of Being—and the problem of art is rethought in such a way that the finish is the return to the start. Heidegger’s focus is the work at work, the unveiling of a thing in truth. For him art transcends the aesthetic valorization precisely in the revelation (as opposed to representation) through which it speaks. So, too, Beckett situates art on the level of the primordial (visual) apprehension of the real. And it is this that accounts for the incongruity at hand: Art fails for the impossibility of expression; yet—as the creative counterpart of the existential ‘I can’t go on, I’ll go on’ at the crux of every Beckett work—its failure is not its end. Rather, art originates precisely therein. This is to say that, to the extent that it is the pre-rational or ante-predicative seizure of the elemental, art, by its very failure to represent, is authentically innovative and retains its potential to be.1

1 – Lois Oppenheim, The Painted Word: Samuel Beckett’s Dialogue with Art (University of Michigan Press, 2000) pp. 77-78

John Minihan, Samuel Beckett, 1985

Three remarks:

1. Like Heidegger’s philosophy (and Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology), Beckett’s thesis is rooted in ontology. Being, then, will be central to my interpretation of Fattovich’s painting, but only implicitly: I leave you to connect the dots.

2. For Beckett, every creative effort is interrogative, meaning it is irreducible to any one meaning. Exploration and openness, then, will be the watchwords of my approach. Dogmatism is the enemy of art.

3. Beckett is painfully aware of ‘the difficulty of uttering the experience of looking at art’1. In his homage to the painter Jack B. Yeats, for example, he writes, ‘In images of such breathless immediacy as these there is no occasion, no time given, no room left, for the lenitive2 of comment. No. Merely bow in wonder.’3 Be forewarned: a Fattovich painting can leave you dumbstruck; bowing in wonder before it testifies to a state of grace.

1 – Lois Oppenheim, The Painted Word: Samuel Beckett’s Dialogue with Art (University of Michigan Press, 2000) p. 67

2 – lenitive: that which soothes or alleviates pain or distress

3 – Samuel Beckett, ‘Homage to Jack B. Yeats’, in Samuel Beckett, Disjecta, ed. Ruby Cohn (New York: Grove Press, 1984) p.149

John Minihan, Samuel Beckett, 1985

TOMMASO FATTOVICH — PAINTINGS 2022-2023

IV. THE DIGNITY OF THE HAND

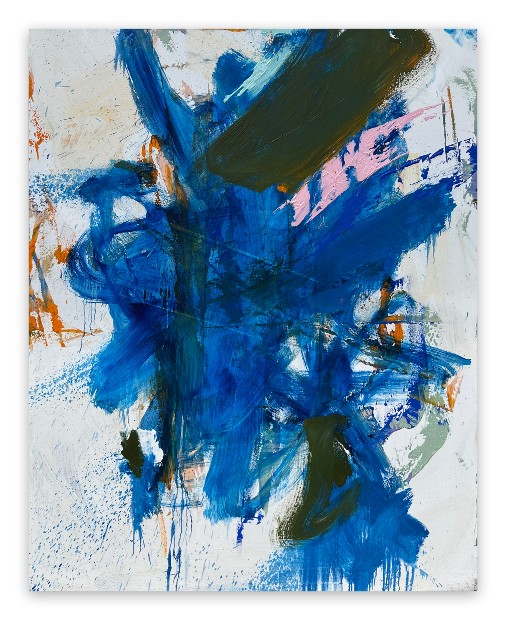

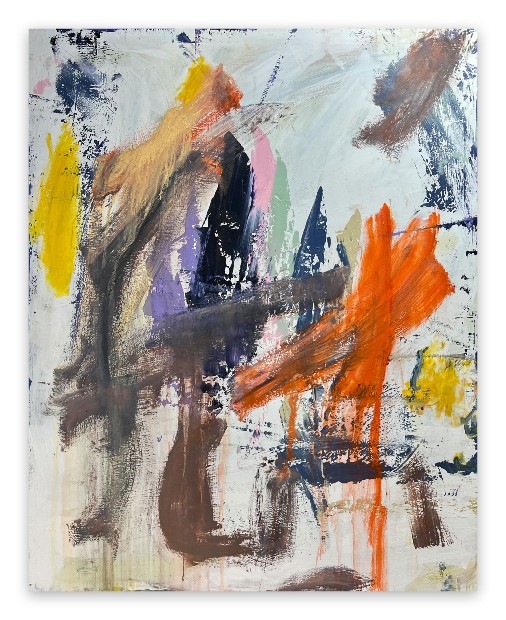

Put simply, Tommaso Fattovich’s defiance of contemporary art can be expressed thus: Where they prefer the readymade, he prefers the handmade. The readymade, as we’ve seen, is but an occasion to express a concept. It is a vehicle for an idea. Ideas are a dime a dozen. For the most part, they are free-floating and anonymous, as disposable and recyclable as your baby’s Pampers—just like the objects-in-context that serve as vectors for them. The ‘facture’ of these objects—be they a taxidermized horse on a wall or a shark in a tank of formaldehyde—is a matter of complete indifference. On that score, Maurizzio Cattelan and Damien Hirst are perfectly interchangeable. Not so for the ‘facture’ of Ingres’ line and that of Schiele, de Kooning’s brushstroke and that of O’Keeffe—in no way are these artists, their works and workmanship, interchangeable. Apples and oranges, you might be thinking: one can’t compare readymades to paintings. You would be right, dear reader, if I were using the term ‘readymade’ in its strict sense: I am not. By ‘readymade’, here, I mean two things: minimal spontaneity in the execution of the painting and minimal trace of the hand in the finished work. By this definition, grid-based and op art paintings are readymades, as are stencil-and-spray paintings and paintings patterned like wallpaper. They are conceptual in that they are preconceived, a visual idea transferred ‘readymade’ to a surface. In them, the brain has relegated the hand to mere executant: inert, it has no say in the making of the painting. Tommaso Fattovich, for his part, restores to the hand its dignity—its capacity to go where its curiosity takes it, its ability to explore and investigate. How do we know that? Just take a look at his paintings, and feel the freedom blowing through them.

Tommaso Fattovich, Dame Mas, 2023

Fattovich’s paintings are animated by an energy that gives them a kinetic quality, at once dynamic and daring. Not the daring of ‘What the fuck’, but the daring of a hand that has used its freedom to create a pictorial space that is in the world but not of it. If that sounds like gobbledygook to you, dear reader, get off your high horse and go directly to Tommaso Fattovich: Abstraction and the Painterly Spark.

Matthew Crawford: For Heidegger, ‘handiness’ is the mode in which things in the world show up for us most originally: The nearest kind of association is not mere perceptual cognition, but, rather, a handling, using, and taking care of things which has its own kind of knowledge. The problem of technology is almost the opposite of how it is usually posed: the problem is not instrumental rationality, it is rather that we have come to live in a world that precisely does not elicit our instrumentality, the embodied kind that is original to us.1

Matthew Crawford: Meaningful work and self-reliance are ideals tied to a struggle for individual agency, which I find to be at the very center of modern life. We worry that we are becoming stupider, and begin to wonder if getting an adequate grasp on the world, intellectually, depends on getting a handle on it in some literal and active sense.2

Gilles Deleuze: ‘The opposite of stupidity is not intelligence, but humility’.3

1 – Matthew Crawford, The Case for Working with Your Hands: Or Why Office Work is Bad for Us and Fixing Things Feels Good (London: Penguin Books 2009) pp. 67-68

2 – Ibid., p. 7

3 –Raphaël Enthoven, ‘Deleuze contre la bêtise’. Macadam philo. France Culture Radio. Paris, 5 May 2006. Translated here by Richard Jonathan

Tommaso Fattovich, Iridescent Armor, 2022

Fattovich brings his paintings into being through sensuous, not cerebral, knowledge. Palette knife, brush, bare hand, scraper: in intimate contact with the canvas, his hand discovers at it discloses, reveals as it conceals, emits silence as it speaks. ‘But where there is danger, there also grows the strength’1: from the unknown into which he allows his hand to lead him, Fattovich brings forth the vibrancy that characterizes his paintings, that painterly spark that flashes when promise and peril encounter. And what remains to keep? The scintillating marks on the canvas, of course, their particular gestural quality, but also the sensuous knowledge that derives from risk assumed. Situated and embodied, Fattovich’s skill, we see, has nothing to do with schooling:2 it comes from the way he affirms the hand’s dignity. The hand, in turn, affirms him in his agency.3 Far from the cerebralism of conceptualism’s ‘artistic propositions’—most of them about as robust as a balloon after a party—Fattovich’s paintings, in their physicality, engage us holistically. The dignity of the hand is evident in them, and as that hand, via the marks it has made, touches us, moves us, our fragmented lives may, however fleetingly, be made whole.

1 – Friedrich Hölderlin, from ‘Patmos’, translated here by George Steiner in his Heidegger, Second edition (New York: Fontana Press, 1992) p. 141

2 – He never went to art school.

3 – Note that there is an ethical dimension to this relation, in that it brings freedom and responsibility into play: it is the hand that makes us human.

Tommaso Fattovich, Surf Solar, 2022

V. THE MATERIALITY OF PAINT

Subject matter—the what—is easy to talk about. But more to the heart of the work, the thing that reveals its nature and quality, is the how, the specific inflection and touch that go into its making. To take a work’s psychic temperature, look at its surface energy. Like syntax and rhythm in poetry, it’s the mechanics that reveal an artist’s character. They determine the way that art will get under our skin, or fail to.

David Salle, How to See: Looking, Talking, and Thinking about Art (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016) p. 15

The narrow intention of what brings an artist to the canvas does not control meaning nearly as much as does the material existence of the picture itself. The experiential dimensions of abstract art—its scale, materials, method of fabrication, social context, and tradition—are crucially important to our understanding of it.

Kirk Varnedoe, Pictures of Nothing: Abstract Art since Pollock, (Princeton University Press, 2006) pp. 251-52

It’s a plastic thing. If intellectual at all, it is fluid, emotional intellect, not analytical. Critics tend to pick things from artists’ work to fit a theory. That’s not how art is made. The artist works from something more direct. It is a visual medium. We don’t need literal interpretation of visual things. Enjoy it for visual, sensual reasons, not literal, interpretive reasons.

Cy Twombly quoted in Paul Winkler, ‘Just About Perfect’. In Cy Twombly Gallery: The Menil Collection, Houston, edited by Julie Sylvester & Nicola Del Roscio, 13–30. (New York: Cy Twombly Foundation/Menil Foundation, 2013)

Tommaso Fattovich, Doors and Distance, 2022

Like all artists, the abstract painter is called upon to create a work that ‘presents at once, with complete authority, the primary illusion of a perfectly visible and intelligible space that is self-contained and independent’ (Susanne Langer; see Tommaso Fattovich: Abstraction and the Painterly Spark). If he or she has difficulty doing this, they may be tempted by the seductions of three common tarts. The first is decorative pattern-making (dolled up in the trappings of postmodernism); the second is ‘special effects’ painting (propped up on the crutches of conceptualism); the last is a funhouse-mirror reflection of the artist emoting (indulged as decadent lyricism). However red their lips, these tarts, one soon discovers, are all bloodless: they’re so anemic they can’t even stand on their own two feet. Nothing surprising in that: a tart’s working position is on her back. For an artwork, however, to be unable to stand on its own two feet is fatal. So, after the dignity of the hand, let us now consider the second factor that makes Fattovich’s paintings so vital: the use he makes of the materiality of paint.

Tommaso Fattovich, Root Down, 2022

Where others are content with the gin-soaked emoting of undisciplined lyricism, Fattovich offers a lyricism that is all the more powerful for being ordered. Francis Bacon:

I think that great art is deeply ordered. Even if within the order there may be enormously instinctive and accidental things, nevertheless I think that they come out of a desire for ordering and for returning fact onto the nervous system in a more violent way.1

Most impressively in his 2022-2023 paintings, this is exactly what Fattovich achieves. The most recent, in particular, ‘return fact onto the nervous system’ with such beauty and fervor that they could serve to demonstrate André Breton’s dictum: ‘Beauty will be convulsive or will not be at all’.2 How does he achieve this? Largely through the way he makes use of the materiality of paint.3 This term, as I’m using it here, embraces three components. The first is the textural effects of the paint on the canvas, all the varieties of mark-making evident on the surface. The second is the traces embodied in the paint of the artist’s engagement in the process of painting—of his arbitration of the fight between chance and reflection, accident and criticism. The third is the evidence in the paint of the movements and sensations of the artist’s body. As Paul Valéry points out, in the act of painting the artist’s body becomes an accessory to their eyes, and the traces of the moving body are the painterly gestures on the canvas.4 Valéry goes so far as to declare that ‘gestural motility—and by extension that of the whole body—are inseparable and indeed indistinct from the mode of existence of the work’.5 The third component, then, of the ‘materiality of paint’ in a work of art is the physicality of the body. Now, dear reader, let me say it again: Fattovich’s use of the materiality of paint is nothing short of breathtaking. As you behold the paintings, may you do so in a state of grace: that was the artist’s state when he painted them.

1 – Francis Bacon in David Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon (London: Thames & Hudson, 1987) p. 59

2 – André Breton, Nadja, tr. Richard Howard (London: Penguin Books, 1999 [Paris: Gallimard, 1928]) p. 160

3 – A word to the wise: To experience just how breathtaking in Fattovich’s paintings is the materiality of paint, you need to behold them directly, unmediated by a screen.

4 – Paul Ryan, « «État en acte». L’esthétique poïétique dans l’art visuel chez Valéry », Studi Francesi [En ligne], 160 (LIV | I) | 2010 (Open Edition Journals)

5 – Ibid. p. 75. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Tommaso Fattovich, The Clouds Will Drop Ladders, 2022

Where others are content with the ‘postmodern’ pattern-making of decorative abstraction, Fattovich offers paintings of tactile presence that maintain a tension between the lushness of color and the rawness of form, and this to scintillating effect. Whether savage or sensual, his brush demonstrates a relish in the physical properties of paint. However spontaneous, his compositions have a tensile strength; however improvised, his marks have an inevitability. On the tightrope of this tension Fattovich is so sure-footed that, to borrow a phrase from Beckett cited above, I can only ‘bow in wonder’. How does he do it? Maurice Merleau-Ponty:

We cannot imagine how a mind could paint. It is by lending his body to the world that the artist changes the world into paintings. To understand these transubstantiations we must go back to the working, actual body—not the body as a piece of space or a bundle of functions but the body as an intertwining of vision and movement.1

To reiterate: It is Fattovich’s embrace of the materiality of paint, in all its ramifications, that accounts in large measure for the wonder of his work.

1 – Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Eye and Mind [L’Œil et l’esprit, Paris: Gallimard, 1961] trans. By Carleton Dallery in The Primacy of Perception, ed. By James Edie (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1964) p. 162 (translation slightly modified)

Tommaso Fattovich, Tippa My Tongue, 2022

Where others are content with the conceptualism of ‘special effects’ painting, Fattovich offers paintings that give the mind a rest from ratiocination. Francis Bacon:

I think that most people enter a painting by the theory that has been formed about it and not by what it is. Fashion suggests that you should be moved by certain things and should not by others. This is the reason that even successful artists—and especially successful artists, you may say—have no idea whatever whether their work is any good or not, and will never know.1

A conceptualist work is dead without an idea to animate it. Fattovich’s work, in contrast, appeals directly to the ‘intelligence of the flesh’. Cathryn Vasseleu paraphrasing Merleau-Ponty:

In painting, vision is not expressive of an object or idea; vision is expressive of itself—its flesh. The dimensions in which we see color, line, contour, and illumination become visible in their own right. It is only by going into the visible, or inhabiting the painting through a dimensionality which is sustained by the visible, that the visibility of painting can be experienced. Painting actually destroys the illusion of disembodied spectatorship by basing visibility in its own carnality, that is by demonstrating that, even as it is his or her own, the seer’s vision is the flesh of the seen.2

And there you have it: The carnality of Fattovich’s painting, manifest in what he makes of the materiality of paint, restores the viewer to an embodied state: it is as a whole person—heart, mind, body and soul—that we take in his painting. ‘The seer’s vision is the flesh of the seen’: ‘When wind and hawk encounter, what remains to keep?’3 That, dear reader, captures the experience of beholding a Fattovich painting.

1 – Francis Bacon in David Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon (London: Thames & Hudson, 1987) pp. 60-61

2 – Cathryn Vasseleu, Textures of Light: Vision and Touch in Irigaray, Levinas and Merleau-Ponty (London: Routledge, 1998) p. 28

3 – Leonard Cohen, ‘As the Mist Leaves No Scar,’ The Spice-Box of Earth, 1961. In Leonard Cohen, Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs (New York: Vintage Books, 1994) p. 15

Tommaso Fattovich, Bodhisattva Vow, 2023

VI. THE AURA OF THE INDIVIDUAL

Cy Twombly: To paint involves a certain crisis, or at least a crucial moment of sensation or release; and by crisis it should by no means be limited to a morbid state, but could just as well be one ecstatic impulse, or in the process of a painting, run a gamut of states. One must desire the ultimate essence even if it is ‘contaminated’. Each line now is the actual experience with its own innate history. It does not illustrate—it is the sensation of its own realization. The imagery is one of the private or separate indulgences rather than an abstract totality of visual perception. This is very difficult to describe, but it is an involvement in essence (no matter how private) into a synthesis of feeling, intellect etc. occurring without separation in the impulse of action.1

Kirk Varnedoe: Twombly’s originality is being himself. He seems to be born out of our time, rather than into it.2

Walter Benjamin’s notion of ‘aura’3 has come in for much criticism,4 but ‘his “mistakes” remain creative, precisely because of the unresolved ambiguities of the “aura” that have yet to be explored’.5 What does Benjamin mean by ‘aura’? In a nutshell, the ‘halo’ of uniqueness and authenticity emanating from an artwork in its original cultural context, before the ‘age of mechanical reproduction’ shattered tradition and brought about a depreciation in the quality of the work’s presence. As I use the term here, ‘aura’ will refer to the ‘halo’ of the artist in the artwork, the evidence of what Cy Twombly calls the artist’s ‘crisis or crucial moment of sensation or release’, his/her ‘ecstatic impulse’ and ‘synthesis of feeling and intellect’.

1 – Cy Twombly, in Nicola Del Roscio et al., editors, The Essential Cy Twombly (London: Thames & Hudson, 2014) p. 67. Originally published as part of ‘Documenti di una nuova figurazione: Toti Scialoja, Gastone Novelli, Pierre Alechinsky, Achille Perilli, Cy Twombly’ in the Italian journal L’Esperienza moderna, no. 2 (August–September 1957) p. 32.

2 – Cited in Joshua Rivkin, Chalk (New York: Melville House, 2018) p. 300. In fact, Varnedoe himself is citing someone else; I haven’t been able to track down the person who made this observation.

3 – Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ in Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, tr. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969)

4 – See, for example, Antoine Hennion & Bruno Latour, ‘How to Make Mistakes on So Many Things at Once—And Become Famous for It’ in Mapping Benjamin: The Work of Art in the Digital Age, ed. Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht & Michael Marrinan (Stanford University Press, 2003) pp. 91-97

5 – Alex Coles, Andrzej Klimowski & Howard Caygill, Introducing Walter Benjamin: A Graphic Guide (London: Icon Books, 2012) p. 140

Tommaso Fattovich, Under the Bridge, 2022

I conceive the artist, here, as an individual, with ‘individual’ defined as ‘idiosyncrasy, embracing the true grandeur of one’s eccentricity; singularity, becoming who one is, the realizing of one’s personal vision’.1 The individual is one who realizes that ‘there is something within us that exceeds the world that we find, and to which we must pay our most serious attention because it is driving us, one way or another, into what we are and will be’.2 All Fattovich’s paintings give evidence of his hand: that hand is the personal hand of an individual, as defined here.

1 – Adapted from Adam Phillips, Going Sane: Maps of Happiness (London: Hamish Hamilton-Penguin Books, 2005) p. 14

2 – Ibid.

Tommaso Fattovich, Poppy, 2022

As his recent work shows, Fattovich has become both a superb colorist and a master of sustaining tension in his compositions. To my eyes, his paintings radiate individuality—a particular sensibility grounded in an affirmed character. The aura of the individual is perceptible in them in the way they at once seduce the viewer and accost him/her—first the kiss and then the confrontation (or the other way around), first the throwing down of the gauntlet and then the sweeping off the feet (or the other way around). In no other paintings, figurative or abstract, do I find the same dynamic: it is the painting that looks the viewer in the eye and dares him/her to be indifferent; it is the painting that extends its hand in welcome and then immediately issues a challenge. This dynamic, as I see it, is the translation of graffiti implicit on the canvas: ‘I was here’. This is the aura of Fattovich the individual. As was said of Twombly, his originality lies in being himself. If you too are an individual, or on your way to becoming one, I invite you to get better acquainted with Fattovich’s work: it will affirm you in your individuality (as all true art does).

Tommaso Fattovich, Galice, 2023

Now, turning from the individuality of the artist to the individuality of the artwork, I offer this exposition by Brian John Martine.1

A good painting is active, it bodies forth a certain mode of being, not in referring to something outside itself, but rather in turning back upon itself to refer to and sustain its own ontological reality. In other words, we can say that the painting is actively engaged in individuating itself. The self-individuating character of the work cannot be penetrated by means of a discursive account. Nevertheless, this facet of the work of art is certainly an undeniable feature of our experience of it. It is precisely this character which is the seat of the power or the life, if you like, which we experience when we are confronted by a painting that works. A thoroughly insistent self-identity lies at the very center of it, and it is translated into our experience as the exhilaration and even perhaps the threat which we know when we stand before it. It is that in the work of art which we experience as ineluctably other. Every good work of art, in exhibiting this facet of its being, declares itself to be independent of external determination. We encounter it as something capable of grounding itself. It supports and sustains itself as a world richly textured, related only coincidentally to what we can call the world.

1 – Brian John Martine, Individuals and Individuality (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1984) pp. 77-85. I have edited these extracts for relevance and readability in this particular context.

Tommaso Fattovich, Superpang, 2023

We recognize that the elements of a painting, however general they may be, take on a peculiar aspect when they are seen as parts of a particular painting. They participate in a universal structure of an intersubjective world, and yet, as a part of the painting, they participate in the mode of individuality which we recognize in the painting as a whole. They remain universal while coming to be at the same time individuated. In other words, these elements, as something integrated into this particular whole, come to be something more than they were before such an integration: more in that they are not only instances of universal elements, but also participants in a relation unavailable to universals as universals. They stand, in a sense, over against themselves. While they might be elements which one could meet elsewhere, they become rich and meaningful as a result of their integral place in the construction of this particular picture. The mode of individuality is made available to them only insofar as they participate in the painting.

Tommaso Fattovich, Making Plans for Nigel, 2022

In presenting a mode of access to the immediate, art offers a kind of expression which can take account of individuality without reducing it to the universal categories of philosophical reflection. It is to this character of the work of art that I meant to point earlier in referring to it as a self-contained ‘whole’ or ‘world’. While we can know and describe works of art in terms of their general characteristics, our experience of them always seems much richer than the general descriptions we construct. The work of art stands in both universal and individual relation to its audience, and can only be fully understood when it is understood as an individual.

Tommaso Fattovich, Fiesta Forever, 2022

When a painter like Tommaso Fattovich makes a painting that works, the ‘aura of the individual’ is intensified manifold. From ‘person’ to ‘individual’ to ‘subject’, the journey deepens as intersubjectivity and humanity deepen. The dignity of the hand humanizes, the materiality of paint embodies, and the aura of the individual makes intersubjectivity (relationship) and humanity (freedom and responsibility) possible. Yes, dear reader, Fattovich’s paintings can not only decorate a dwelling, they can also heighten the humanity of its inhabitants.

Tommaso Fattovich, Playing with a Stick of Dynamite, 2023

VII. CONCLUSION

Contemporary art has, perhaps, had its heyday. The quarrel about it seems to have died down. Its founder, Marcel Duchamp, had the honesty to abandon art when he had said all he had to say. Very few of those who walk in his wake have had the integrity to do likewise. The comeback of painting continues as the conceptualists become less strident. Their ‘transgressions’, whether adult or juvenile—religious and philosophical or sexual and excremental—now barely cause a stir. And yet it remains a fact that contemporary art’s impact has been massive. For better of for worse? Each of us has their opinion. For my part, what concerns me in the current environment is the fate of artists who have found a voice but not an audience. The alliance of contemporary art and hyperconsumerism has, I’m convinced, intensified the ‘winner-takes-all’ phenomenon. ‘When the poets are forgotten the mathematicians will still be remembered’: My ideal is to live in a world where both Hilbert and Shakespeare, Euclid and Aeschylus, Gauss and Goethe have pride of place. The fact is, however, that while engagement with art as a consumer is booming, engagement with art as an individual seems to be in terminal decline. Which is why, when I look at Fattovich’s work, I get excited. This, for me, is art that can grab a consumer and turn him/her into an individual, or at least set them on that path. My task in this essay has been to clear a path for you to Fattovich’s work.

Tommaso Fattovich, Wimbledon, 2023

So, have I convinced you, dear reader, that Fattovich’s ‘joy of painting’ is as exciting as the ‘joy of sex’? The ‘struggle mouth-to-mouth and limb-to-limb’,1 the luxuriousness of leisurely love-making? If contemporary art is fuck-and-run, Fattovich’s painting is a coup de foudre: a lightning strike, love at first sight, long-lasting and far-reaching. Of course, if won’t be so for everyone. But I do hope it will be for you.

1 – Leonard Cohen, ‘Paper-Thin Hotel’, Death of a Ladies’s Man (Warner Bros. Records, 1977)

Tommaso Fattovich, Giraffe, 2023

VIII. CODA – A SHORT INTERVIEW WITH TOMMASO FATTOVICH

Excerpts from an interview with Tommaso Fattovich conducted by Richard Jonathan in July 2023

How often do you paint?

I paint every couple of months, and I do several pieces over the course of a week-long binge. I do it this way for several reasons. One, the time away from painting makes me want to paint even more, but it’s also necessary in order to regroup mentally and recharge, and ultimately to find new ways of developing the work. Two, I work intensely on multiple pieces and never leave the studio until they are done. It’s very draining, physically and emotionally. Lastly, there’s a financial reason: oils, paints, brushes, canvases and all the material used is costly, so I need to make some pieces, sell some pieces, then paint again. Each painting session is ritually planned in advance. That entails making music playlists, buying new materials and getting into the correct mental space to be fully engaged with what I am doing. Once I am in the studio, no distractions allowed! I must be alone, alone with my thoughts and feelings.

Brick, 2023 | Tommaso Fattovich | Clay Pigeons, 2023

You used the term ‘emotionally draining’. Could you describe the emotions you experience during the course of making a painting?

‘Emotionally draining’ refers especially to the challenges of creating a painting and knowing when it’s done. The emotion is anxiety wrapped up in joy. Basically, I start off in a panic, almost as if I have run out of ideas or forgot how to paint (that’s the anxiety part). The anxiety at times is compounded by knowing that if I don’t produce something good I have wasted time and money, and my galleries will be disappointed (all real conversations in my head).

However, the anxiety is wrapped in a blanket of joy, because when I am painting I am alone and the possibilities are endless—that gives me comfort. The decisions are mine to make. The joy also comes, of course, from the pleasure of creating, and rising to the challenge.

Is there a typical ‘emotional trajectory’ from start to finish?

Yes. It begins with excitement. Then the panic starts, leading to anxiety. Then, as the work progresses, it becomes a pleasure. But there’s violence—making a painting is like breaking in a horse! When it works, it’s pure joy—peace, because the battle is over, then joy.

And if you had to single out one overriding emotion in the course of your making a painting, what would it be?

Free. Feeling free.

Mad Beef, 2022 | Tommaso Fattovich | Soy un guerrero y busco peligro, 2022

RELATED POST IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

FATTOVICH WORKS | IDEELART

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments