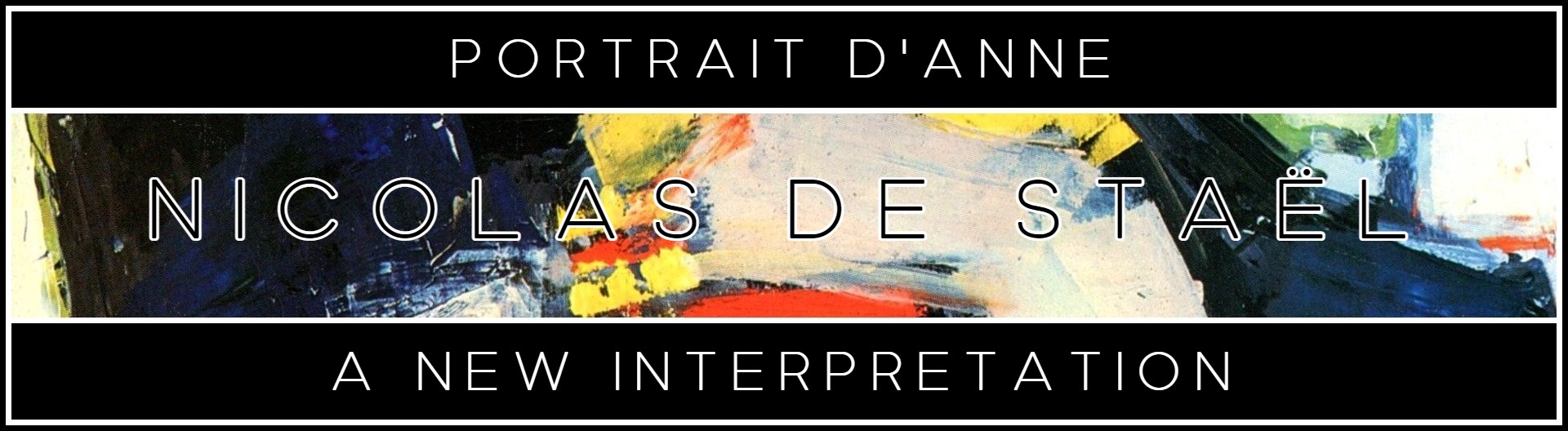

PART I: RICHARD JONATHAN: NICOLAS DE STAËL, PORTRAIT D’ANNE – A NEW INTERPRETATION | PART II – JOHN RICHARDSON ON NICOLAS DE STAËL

ART OF THE PORTRAIT II

PART I – NICOLAS DE STAËL, PORTRAIT D’ANNE: A NEW INTERPRETATION

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

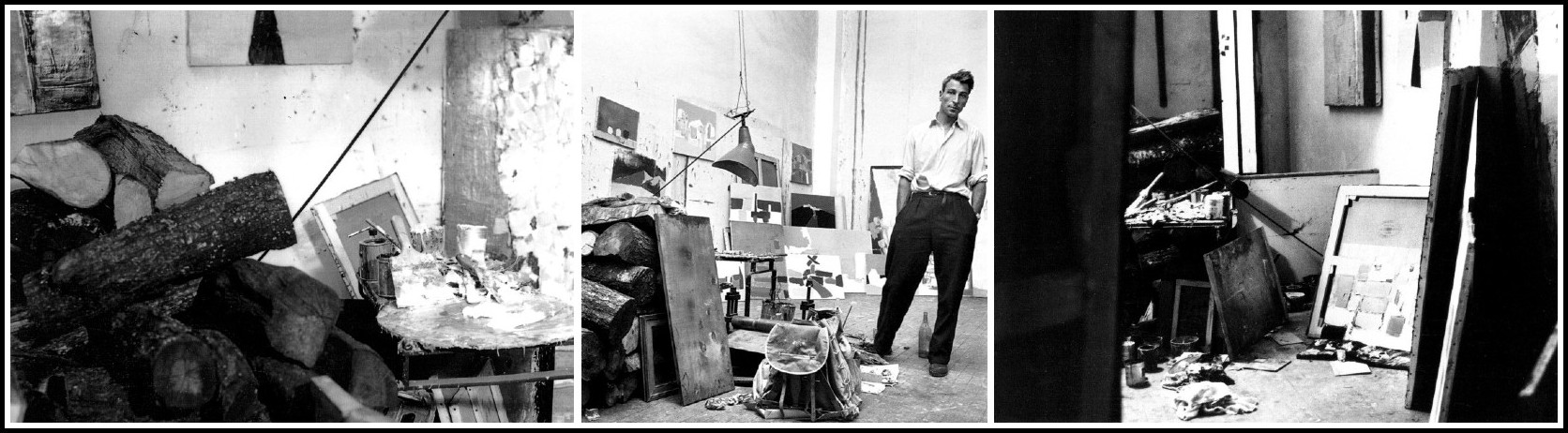

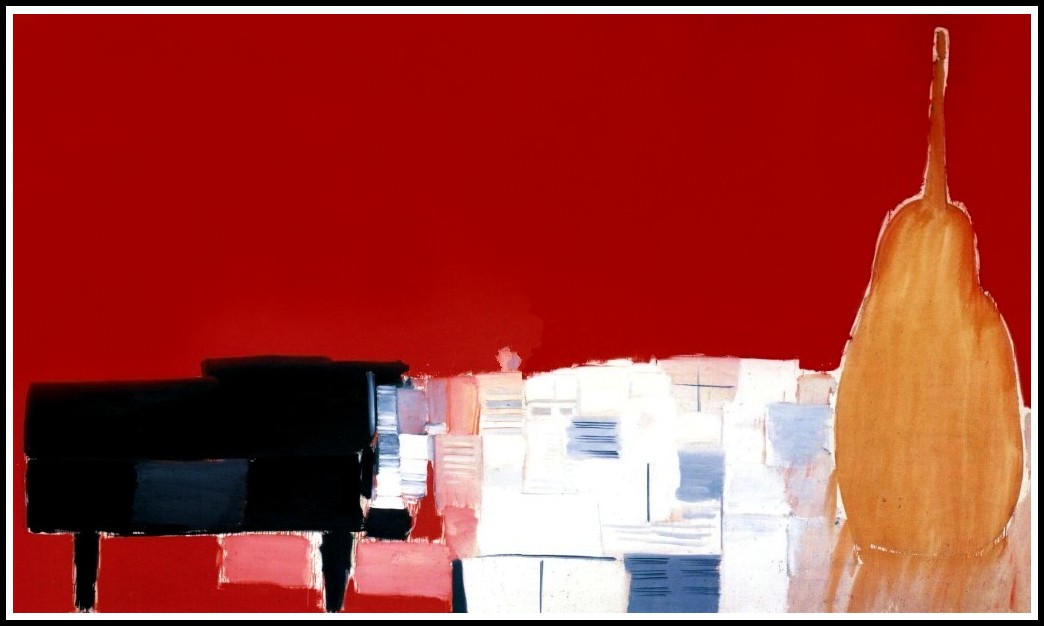

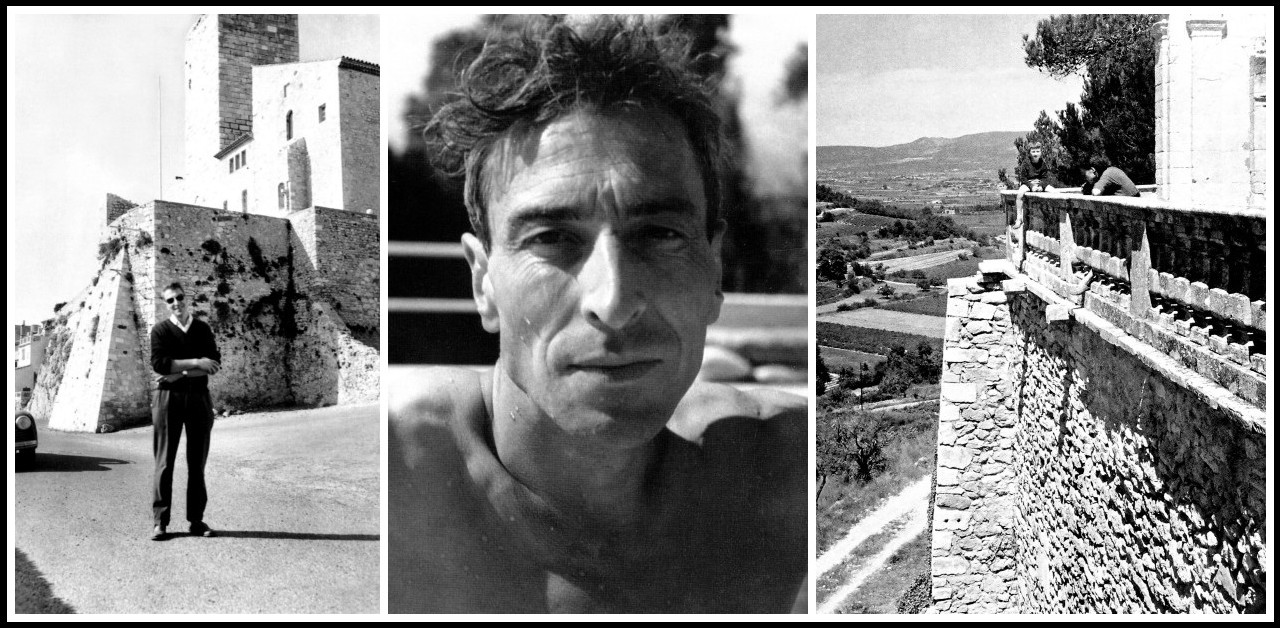

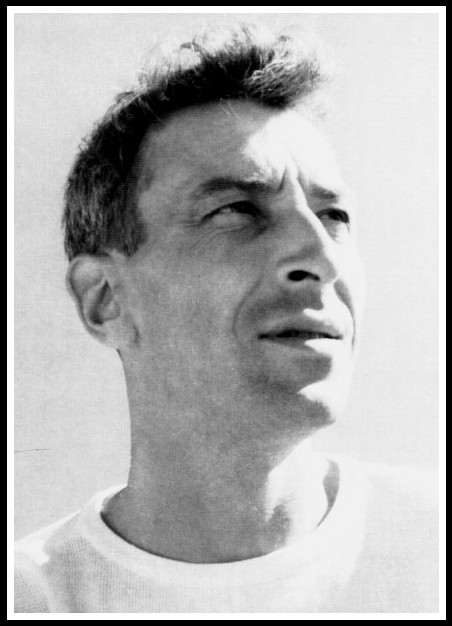

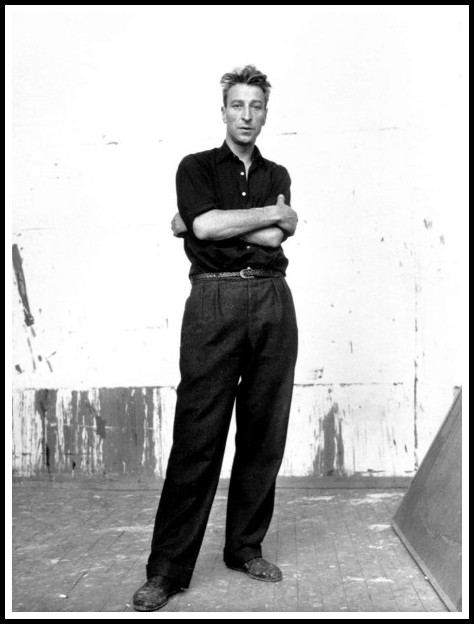

L’atelier rue Gauguet, 1953 | Nicolas de Staël, 1954 | Photos: Denise Colomb

I. INTRODUCTION

There is a certain sleight-of-hand in slipping Nicolas de Staël into a series on ‘the art of the portrait’, for in fact, while he drew a few portraits early in his career…

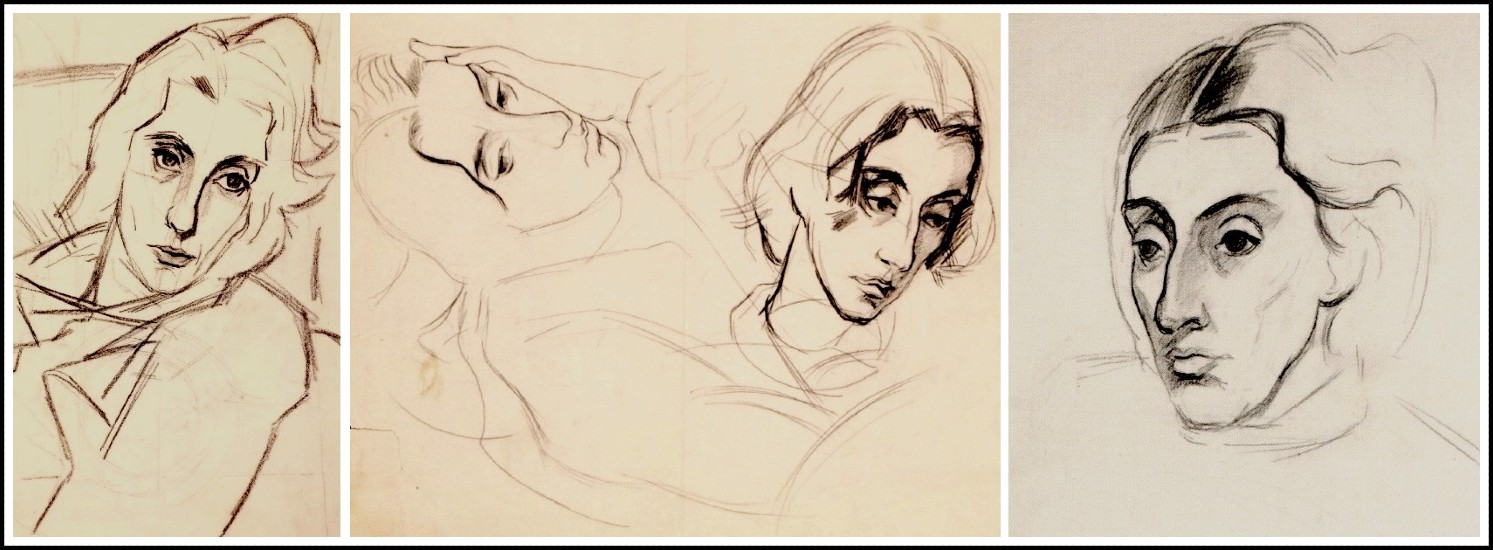

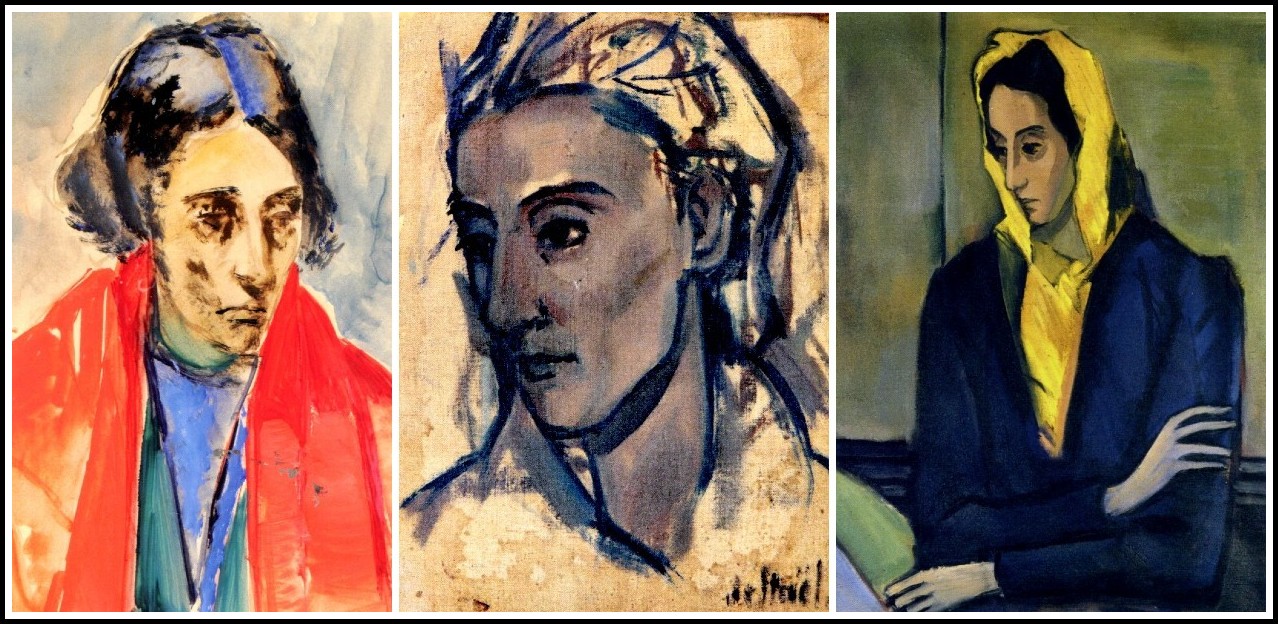

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait de Jeannine, 1939

… he painted hardly any. The only extant ones, according to the Catalogue raisonné (1997), are the Portrait de jeune Arabe (1937) and the three Portrait de Jeannine (1939, 1941, 1941-42).

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait de Jeannine, 1939, 1941, 1941-42

As for Portrait d’Anne (1953), to classify it as a portrait is to stretch the restricted definition of the term I am using in this series on the art of the portrait: a portrait must show the face, with ‘face’ understood as Emmanuel Levinas defines it:

‘A face is that which in the other regards me, reminding me, from behind the countenance he puts on in his portrait, of his abandonment, his defenselessness, and his mortality, and his appeal to my ancient responsibility, as if he were unique in the world, beloved.’1

And as John Berger describes it:

‘Drawing a face is one way of noting down a biography. Good portraits are both prophetic and retrospective. Every trait on a face is in a state of suspension between memory and expectation. Nothing else in the world quivers with such complexity as the living human face, and its quivers are like waves crossing the sea of a lifetime, so that the person drawing becomes an observer, at the water’s edge, on all the shores of the life of that face. And the more the waves enter the drawing, the less the face will remain a mask.’2

1 – Emmanuel Levinas in Jill Robbins, ed., Is It Righteous to Be? Interviews with Emmanuel Levinas (2001, Stanford University Press) p. 204

2 – John Berger, Portraits: John Berger on Artists (2021, Verso Books, Kindle Edition) p. 606

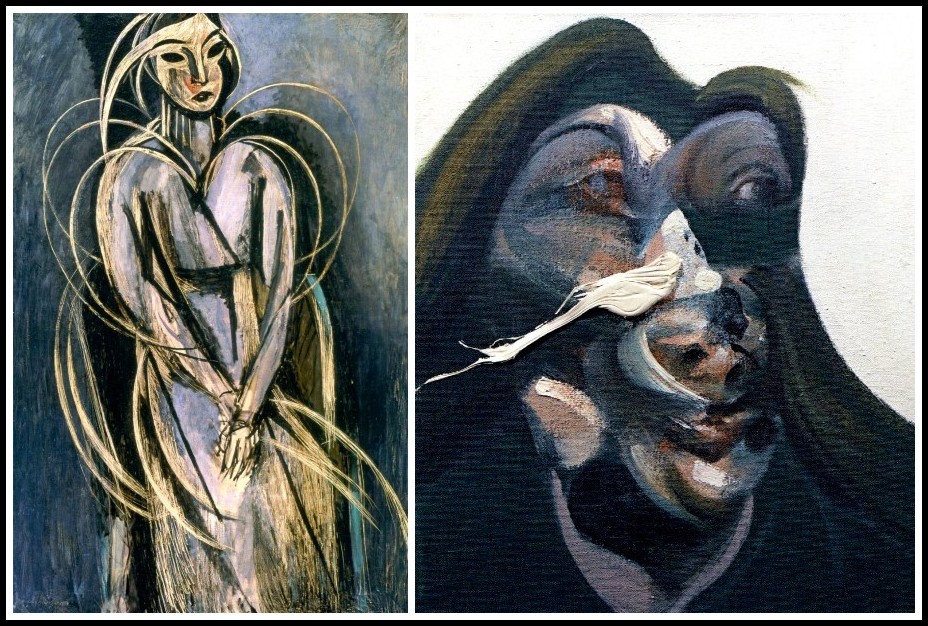

Henri Matisse, Yvonne Landsberg, 1914 | Francis Bacon, Study for the Head of Isabel Rawsthorne, 1967

My interpretation of Portrait d’Anne can be expressed in two theses.

THESIS 1: Portrait d’Anne is both a portrait and a self-portrait.

THESIS 2: Portrait d’Anne functions as a face as defined by both Emmanuel Levinas and John Berger, despite the fact that no face is shown in it.

I will not proceed in linear fashion, developing one thesis and then the other; instead, I will argue the two theses simultaneously, or, as in cinema, cut between the two. As my interpretation of the painting has much to do with time, I will also employ flashbacks and flash-forwards. All this, dear reader, in an effort to reach you more effectively. Are you ready? Let’s go!

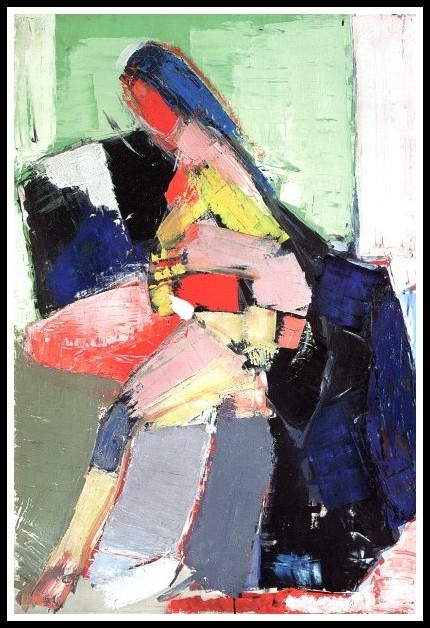

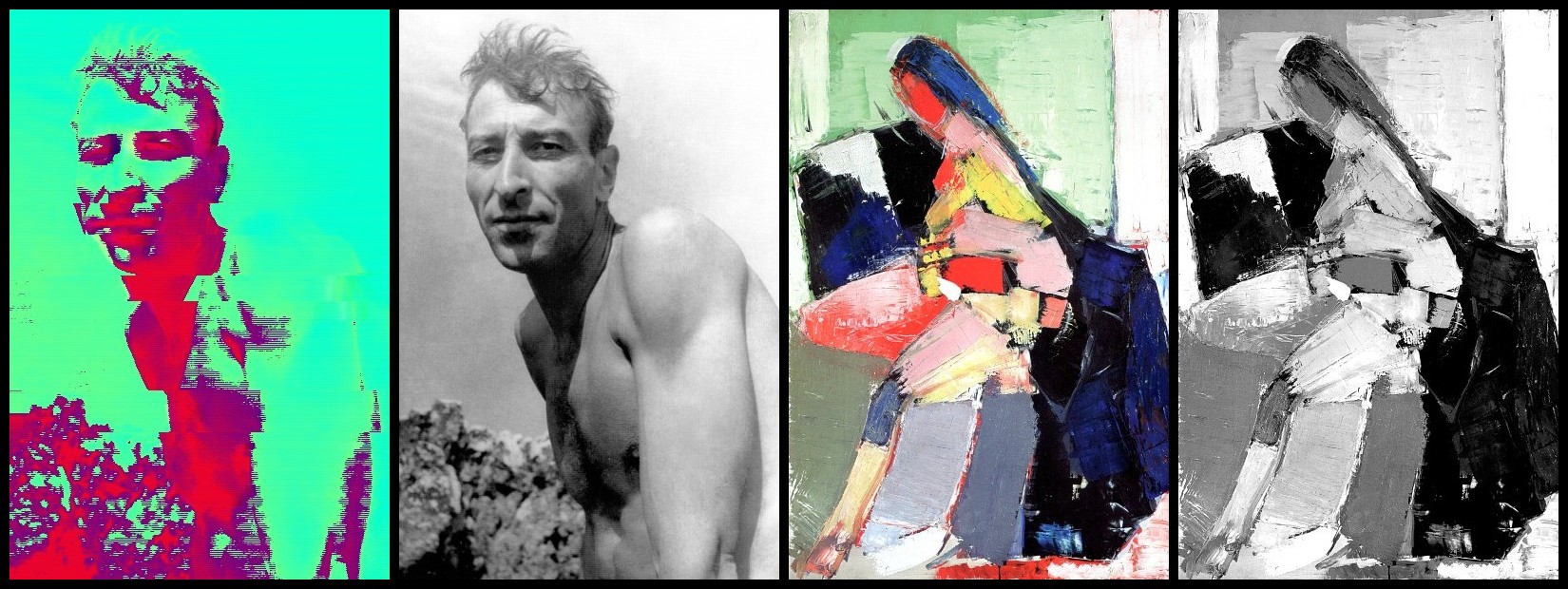

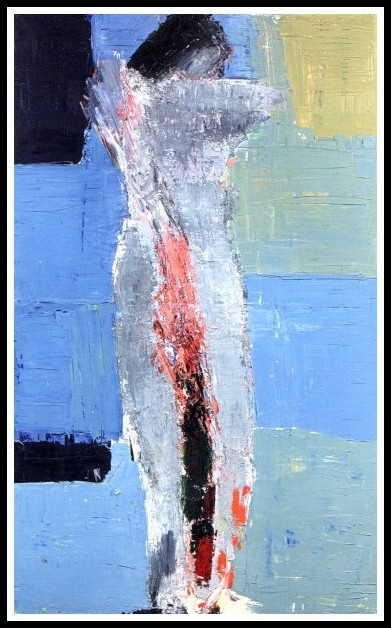

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953

II. BIOGRAPHICAL FACTS THAT INFORM THE INTERPRETATION

I will now provide, in this paragraph and the following six, a series of biographical facts*—mostly in the words of both Nicolas and Anne de Staël—that will inform the discussion to follow. Anne de Staël was born in Nice on 24 February 1942. Her father, Nicolas, was then 28, while her mother, Jeannine Guillou, a painter, was approaching 33. The parents had met in Marrakesh in August 1937. Jeannine had been married to the Polish painter Olek Teslar since 1928; they had a six-year-old son, Antek. Jeannine left Olek for Nicolas, taking Antek with her. On 27 February 1946 (three days after Anne’s fourth birthday), her mother, then 37 years old, died of heart failure while undergoing a therapeutic abortion (very frail, she’d been chronically ill, and had had a severe case of pneumonia just weeks before). Nicolas was devastated (Radio France: ‘Jeannine Guillou et Nicolas de Staël: la rencontre’.) Three months later (22 May 1946), Nicolas married 21-year old Françoise Chapouton (at 19, she’d been tutor to Antek; then, when Jeannine was too weak to look after the children, she took care of Anne and Antek). The couple would go on to have three children: Laurence (b. 6 April 1947), Jérôme (b. 13 April 1948), and Gustave (b. 3 April 1954). Five years older than her nearest sibling, and with her mother dead, Anne was very much her father’s daughter.

* My main sources, the citations from which I have translated (and sometimes edited for clarity and concision), are:

1 – The letters of Nicolas de Staël: Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955. Édition présentée, commentée et annotée par Germain Viatte (Gouville-sur-mer: Le Bruit du Temps, 2016)

2 – Anne de Staël’s biography of her father in Françoise de Staël, Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint (Neuchâtel: Éditions Ides et Calendes, 1997) pp. 59-171

3 – Anne de Staël’s memoir of the family’s time in Provence, ‘Je suis plus byzantin que latin’ in Nicolas de Staël en Provence, (Paris: Éditions Hazan – Culture Espaces, 2018) p. 105-112

4 – Anne de Staël’s study of Nicolas de Staël’s paintings and drawings, Du trait à la couleur (Paris: Imprimerie nationale Éditions, 2001)

5 – Laurent Greilsamer’s biography of Staël, Le Prince foudroyé: La Vie de Nicolas de Staël (Paris: Fayard, 1998)

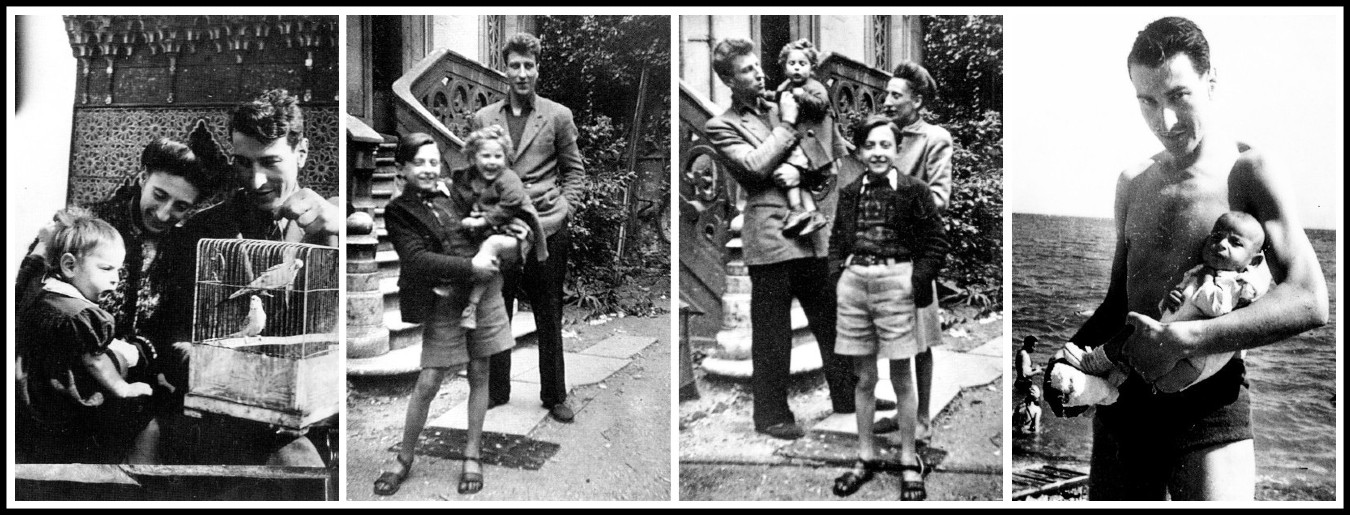

Nicolas de Staël, Anne de Staël, Jeannine Guillou, Antek Teslar, 1942-43

In mid-July 1953, Nicolas de Staël, at the suggestion of his friend, the poet René Char, rented a house in the village of Lagnes (Vaucluse, Provence). Anne de Staël: ‘René Char put him in touch with his friends of long-standing, the Mathieu, who owned a country house and a large parcel of farmland, ‘Les Camphoux’, just outside Lagnes. Staël met all the family, which included a married daughter, Jeanne Polge.’1 Nicolas de Staël: ‘Jeanne came towards us with such vigorous qualities of harmony that we are still dazzled by them. What a girl, the earth itself is moved; what a singular cadence in the sovereign order.’2 (For a fancy prose style, you can always count not only on a murderer3, but also on a man in love.) The editor of Staël’s letters, Germain Viatte, is more direct: ‘Staël immediately fell under the spell of Jeanne’s beauty and enigmatic personality; she soon became his model, and then his lover’4. A month later, Staël embarked Jeanne together with his wife Françoise, their three children, and a painter friend, Ciska Grillet, in his newly acquired Citroën van and set out for a month-long tour of Italy. Germain Viatte: ‘This bizarre travelling party was motivated, it would seem, by the distraught artist’s dream of reconciliation between his family life (Anne de Staël remembers Françoise’s happiness when she told her husband that she was pregnant) and his emerging passion (Anne also remembers her father’s air of strange absence whenever he returned from a visit to Les Camphoux)’5. Upon their return from Italy, Staël decided, after a brief stay with his family in Paris, to move to Lagnes alone. Anne de Staël: ‘Staël was still looking for a house in Provence. He saw the Matthieu often. An affair developed between Nicolas and Jeanne. She became his model and inspired great paintings: Nu debout, Figure debout, Nu couché, Nu-Jeanne’.6

1 – Anne de Staël in Françoise de Staël, Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, p. 139

2 – Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955, p. 457

3 – Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita (Penguin Books, 1981 [1955]) p. 9

4 – Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955, p. 458

5 – Ibid, p. 465

6 – Anne de Staël in Françoise de Staël, Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, p. 143

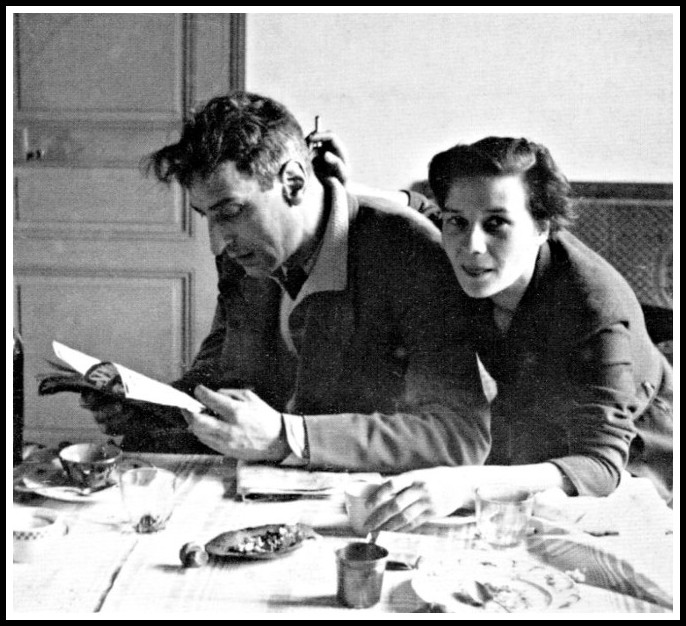

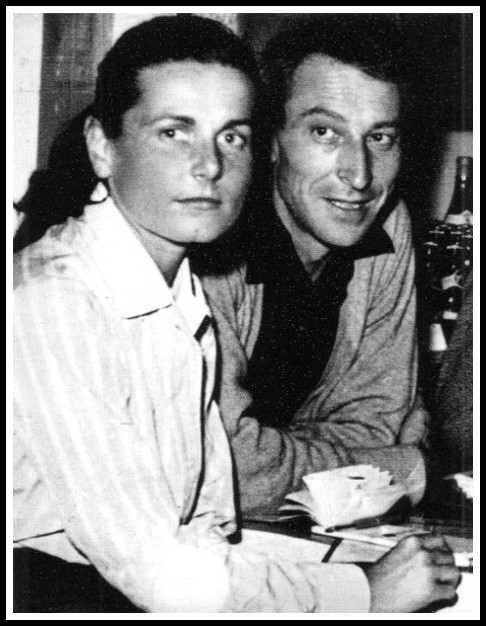

Nicolas & Françoise de Staël, 1951 | Photo: Poune Ratel

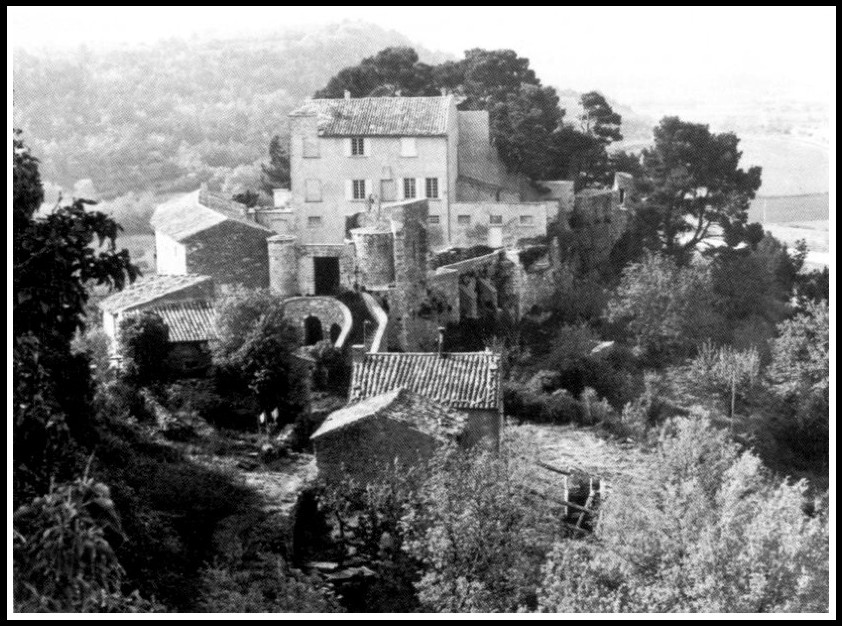

In November 1953, Nicolas de Staël bought le Castelet in Ménerbes, which had been the country house of the Mathieus’ dentist.

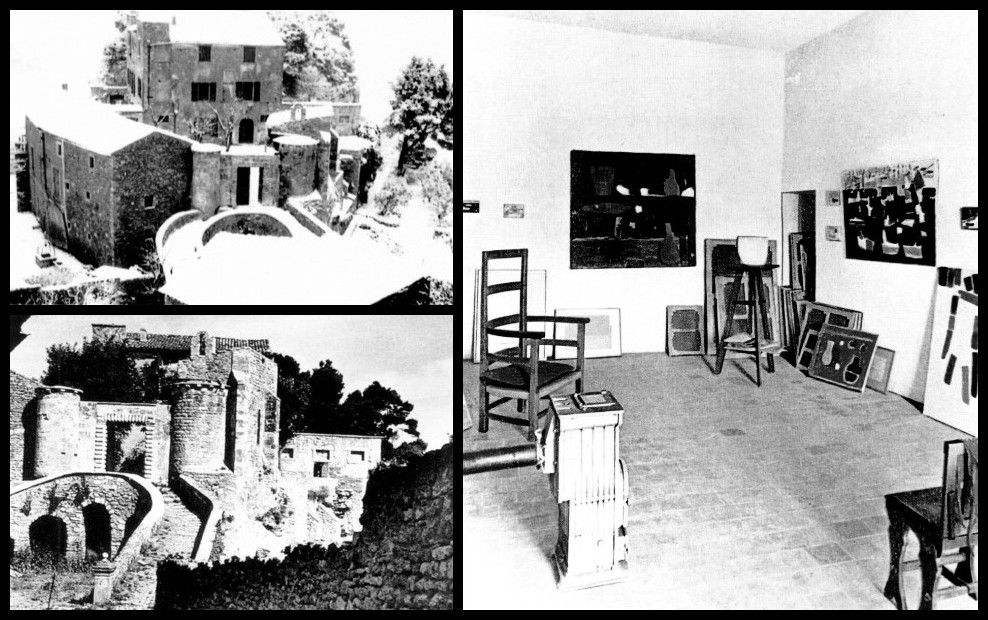

Ménerbes, Le Castelet, 1953

Six months later, in May 1954, he wrote to Françoise (who’d given birth to their son, Gustave, in April): ‘Lots of tenderness for you with the children and the way things are going without me.’1

1 – Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955, p. 562

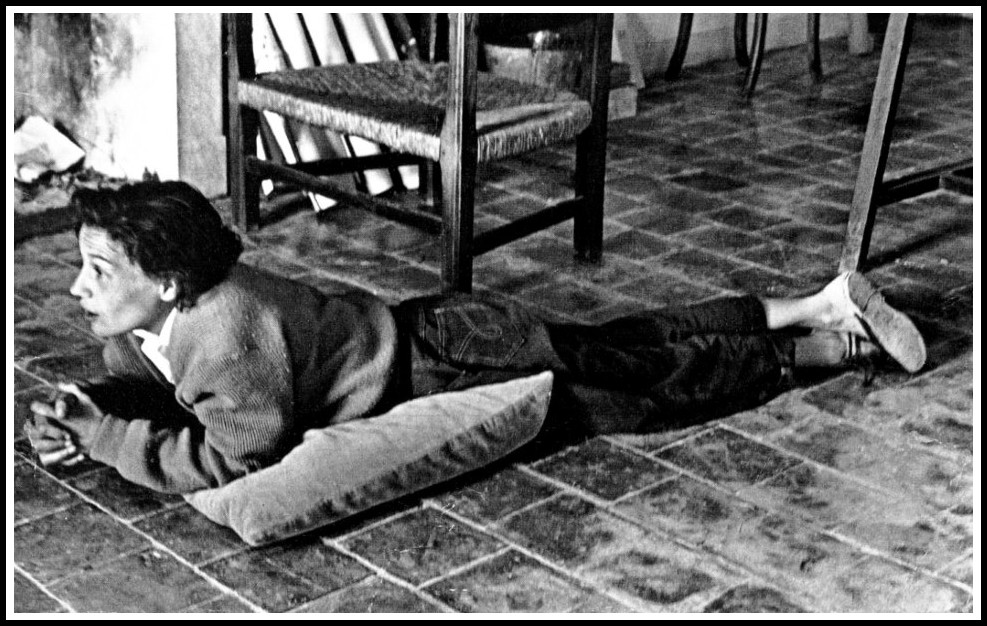

Françoise de Staël, the studio in le Castelet, Ménerbes, 1956 | Photo: Lynn Chadwick

For him and Jeanne, however, things were not going well: Jeanne, married with two sons aged ten and eight, refused (unlike Jeannine in Marrakesh) to leave her husband and children for him. Laurent Greilsamer: ‘He wanted to reconcile the irreconcilable and live with both Françoise and Jeanne. Françoise refused. Jeanne for a time seemed to believe it possible: “Let me be godmother to your children”, she asked Françoise.’1 From that moment on, in the grip of a passion he couldn’t overcome, his life became (as he himself was wont to say) a living hell. Anne de Staël, in what seems like a premonition of the end, recounts an incident in Sicily when—after a violent argument between Nicolas de Staël and the temple-ruins caretaker in Selinunte (who had refused, it being past closing time, to let the Staël party into the grounds)—they went swimming: ‘The sea at the end of the day was like leaden air. I saw my father swimming out into the velvet, the oil and the lead of the sea, swimming out alone, very far. The night was closing in on the sea. For me, no return was possible, and in fact he never came back.’2

1 – Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé: La Vie de Nicolas de Staël (Paris: Fayard, 1998) p. 253

2 – Anne de Staël, Du trait à la couleur (Paris: Imprimerie nationale Éditions, 2001) p. 257

Jeanne Polge & Nicolas de Staël, Vaucluse, 1953-54

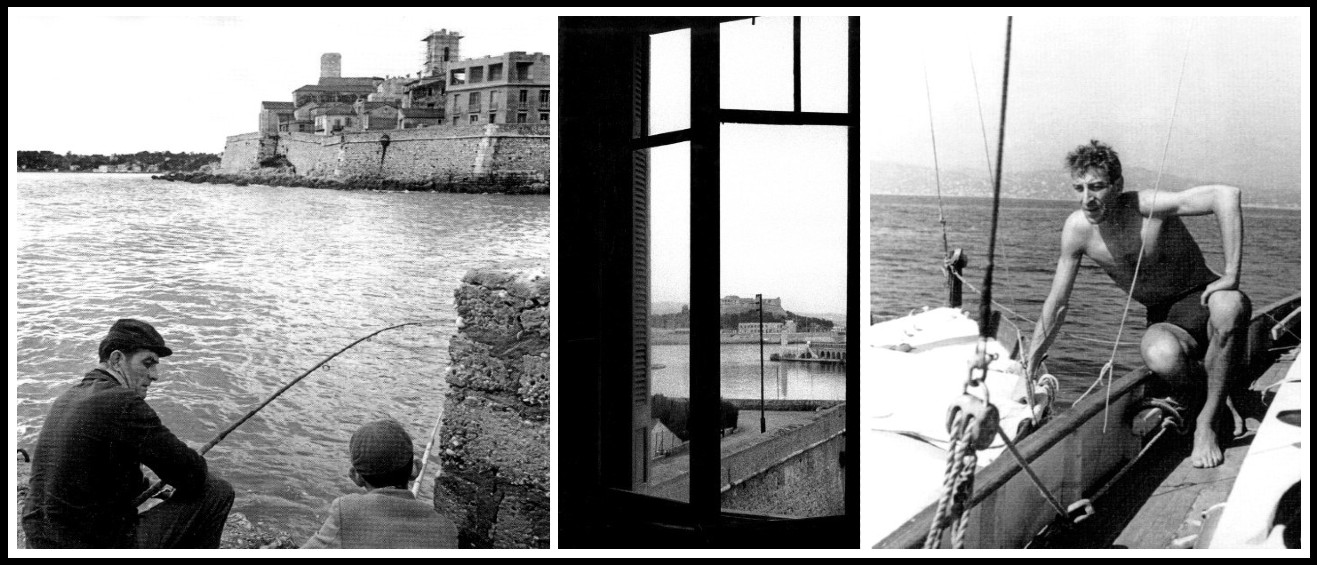

To get away from Nicolas, Jeanne and her husband, Urbain, left the village of Lagnes to go and live in the town of Grasse. Staël followed them, looking for a studio for himself in the vicinity of Grasse, Cannes or Mougins, and finally settling for one in Antibes. Nicolas de Staël to René Char: ‘I have become, body and soul, a ghost who paints Greek temples and a nude from no model so adorably haunting that it ends up obscured by a veil of tears.’1 And again: ‘There are women who only show themselves the way stars do, alone in the intimate firmament. I love her to death.’2 Nicolas de Staël to Pierre Lecuire: ‘I can no longer sleep. The heart is off-kilter’3. And again: ‘Don’t tell me you know what women are. At our deaths we will be none the wiser about them. Waiting for God and Saint George to help us.’4 Nicolas de Staël to Jeanne Polge: ‘I sense you have unconsciously understood since childhood how much disturbance, lies, and perversity enhance your femininity. I think you are afraid to live with me because you know the armature of your sensibility becomes immovable in the face of a prospective change in the order of things, and you dream. I think you feel very intensely that the complications of your married life give you a form of femininity that puts me in a state of hopeless love, and that you don’t want me to be free of this hopelessness because it belongs to you like a book, a book you cherish all the more because you know the ending.’5 In wanting to be loved by Jeanne, Nicolas does everything to make himself unlovable: the paradox of every spurned lover since the dawn of Romanticism.

1 – Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955, p. 474

2 – Ibid, p. 487

3 – Ibid,, p. 510

4 – Ibid, p. 537

5 – Ibid, p. 559-60

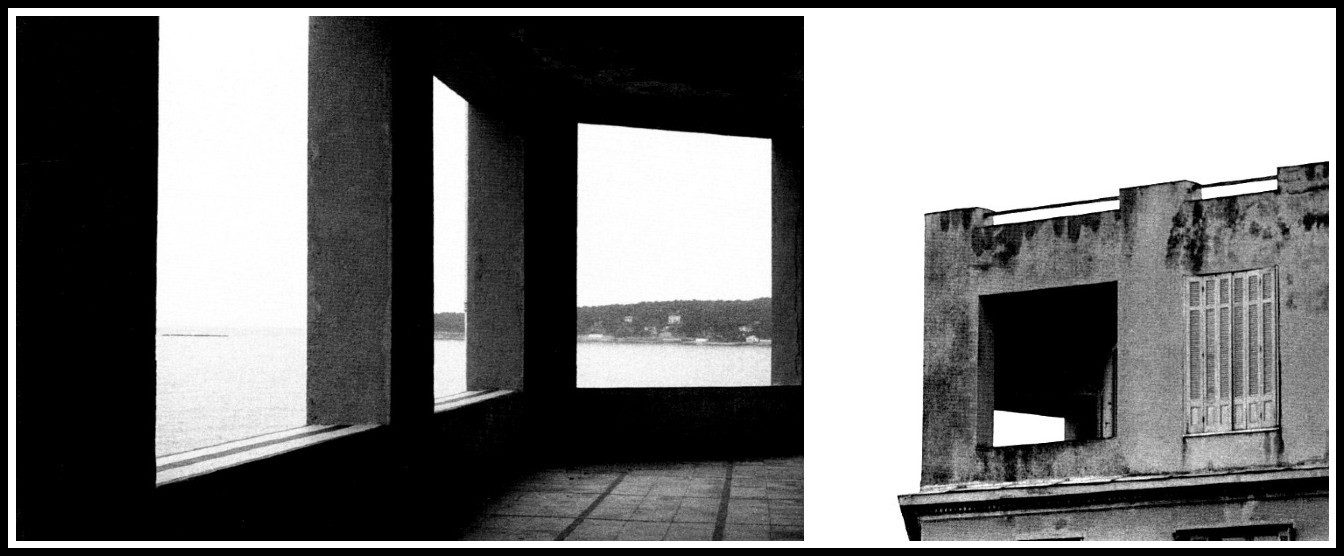

The ramparts, Antibes, Staël’s studio, 2nd floor, Maison Ardouin | View from studio interior | Nicolas de Staël, 1954-55

Nicolas de Staël to his wife Françoise: ‘At the bottom of it all I am trying to prove something to myself. Is that natural? Is it monstrous? How to know how far my passion will go? How to reduce the intensity of you missing me? How not to become a ghost to the children? How to live where I feel alive?’1 To Pierre Lecuire: ‘I cannot look at Françoise and the children while thinking all the time of Jeanne because that’s impossible for me.’2 And to Jeanne: ‘You’re in my blood, you flow in every vein.’3 And again: ‘Pardon me for not being dead. There is no sky in which you are not absent. I’m going to try to rid myself of every trace of you. Help me if you can.’4 Addressing the dead painter directly, John Berger, in his homage to Nicolas de Staël, wrote: ‘Many of the later paintings represent absence. Like the blue reclining nude painted without a model in 1955. A woman on the other side of the mountains and you before the glacier.’5 That captures the kernel of this doomed love affair.

1 – Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955, p. 582

2 – Ibid, p. 595

3 – Ibid, p. 579

4 – Ibid, p. 605

5 – John Berger, Portraits: John Berger on Artists (London: Verso Books, Kindle Edition, 2021) p. 522 (my italics)

Nicolas de Staël, Nu couché bleu, 1955 | ‘A woman on the other side of the mountains and you before the glacier.’

Nicolas de Staël to Herta Hausmann, early November 1954: ‘My wife is digging in her heels, forbids me to write to the children and asks me to stop seeing them. Jeanne joyfully fucks Urbain and sends me tender words of fidelity that I respond to in the hope of seeing her one day. I can’t get that bitch out of my blood; still, I keep working.’1 Nicolas de Staël to Pierre Lecuire, 27 November 1954: ‘Don’t fret about me, one rebounds from the undertow if the swell permits it. I’ll remain here because I’m going to go, without hope, to the depths of my heartbreak, to the tenderness in it depths.’2 Nicolas de Staël to Jeanne Polge, December 1954: ‘Jeanne my love, I am risking a prestigious name, a prestigious family, my talent as a painter, and my life for you. You, for your part, are trying to cut everything that exceeds you down to your size, to enable you to continue to love yourself. Dearest, you are an idiot. I don’t know what you call “making giant strides”. You haven’t moved an inch since I met you. I love you.’3 On Friday, 4 March 1955, Nicolas de Staël drove from Antibes to Paris to attend two Webern and Schoenberg concerts as well as a talk by Pierre Boulez. Thrilled by the new music, he took care of some business in Paris then returned to Antibes and began making preparatory drawings for what would be his last painting, Le Concert.

1 – Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955, p. 619

2 – Ibid, p. 631

3 – Ibid, p. 648-49

Nicolas de Staël, Le Concert, 1955

Germain Viatte: ‘Nicolas de Staël knew that despite many hesitations and regrets, Jeanne, however fragile her will, had made an irrevocable decision. After months of passionate reproaches, he knew deep down that she was not held back by social convention alone, but by something more serious As for himself, he found that his decision to break with his family weighed on his conscience.’1 On 15 March 1955, Nicolas de Staël took an overdose of sleeping pills but failed to kill himself. The next night, after leaving a note for Anne informing her of the inheritance she was entitled to (she was born out of wedlock), as well as one for his dealer that declared, ‘I don’t have the strength to finish my paintings’2, he threw himself off the terrace of his studio. At age forty-one, having produced over a thousand paintings in ten years, Nicolas de Staël was dead.

1 – Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955, p. 684

2 – Ibid, p. 685

Nicolas de Staël, studio & rooftop terrace, Antibes | Photo: Denise Colomb, 1955

III. INTERPRETATION

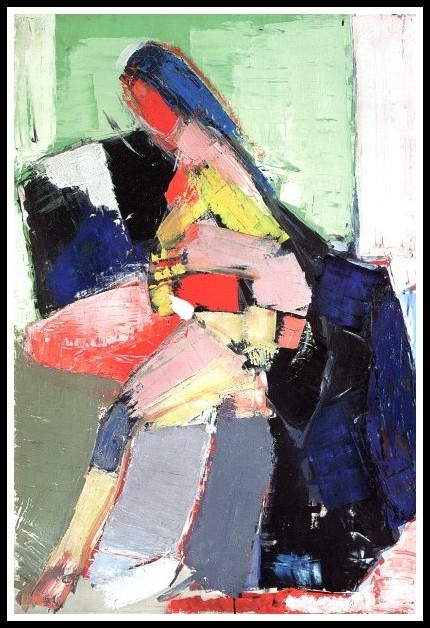

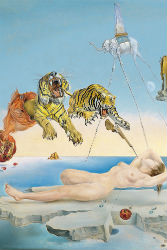

Now take another look at Portrait d’Anne. What do you see? For my part, things go like this: Immediately my eyes configure the forms into the shape of a girl. She radiates a virile femininity, moving forward with determined stride. She’s tall, thin, in the midst of a mission to get somewhere. If you’re looking for an assassin, she might fit the bill; if you’re looking to get laid, look elsewhere: on the man of her secret fancy, solely, will she bestow her submission. Then again, bum on a bench, she could simply be half-seated, waiting to confront the interrogator between her and the torture chamber: in a game of chess, she’d beat the bastard. She can’t be riding a horse, for she’d never ride side-saddle: a horse between her legs is more what she goes for. Now what’s that black and Prussian blue she seems to be emerging from? Could it be a man’s jacket? It’s in her past, but in her future too. Is it just me who can project the features of a face—chiseled cheekbones, finely-cut lips, oracular arch of the eye—into the red oval of her face? If the milky verdigris sets off her beauty, the other colors say the lily needs no raiment. There’s something vampiric in the red, but the blue says you’re barking up the wrong tree: if blood is her element, it’s for its pulse, not its substance. See how she disrupts the play of diagonals, refusing to be confined in line? And there’s something Zen about her: quietude in turmoil, refusal of closure. There’s still some clutter, but it seems to be coalescing—into what? A thoroughbred beauty? A thief at a crucifixion? A ghost of a man in the guise of a girl?

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953

Nicolas de Staël was seven when his father died, eight when his mother died. Anne de Staël, as we have seen, was four when her mother died. The parallelism is significant, I suggest, only to the extent that it intensified the relation between father and daughter. Staël painted Portrait d’Anne in July 1953 (his daughter was not yet twelve), shortly after Jeanne Polge first swept him off his feet.1 In Le choc amoureux2 Francesco Alberoni writes that one falls in love when one wants to change one’s life. If that is true, then in July 1953 Nicolas de Staël was already in a state of turmoil: he wanted to change his life.3 This, I suggest, accounts for his seeing himself in his daughter: wilful, headstrong, refusing to be held back; proud, dignified, unafraid of the fire to come. Appearing to be in her late teens, Anne is portrayed as the dynamic young woman Staël hoped his eleven-year-old girl would become. Look at the painting again. Do you see how, in its entirety, it vibrates with the tension between past, present and future? So if, as John Berger argues, ‘in a good portrait, every trait on a face is in a state of suspension between memory and expectation’, then Portrait d’Anne, despite showing no face, functions, in its mingling of past, present, and future, as a face. Henri Bergson: ‘It is not from the present to the past, not from perception to recollection, but in the other direction we move’.4 In Portrait d’Anne, Nicolas de Staël replaces ‘recollection’ with ‘expectation’, and in so doing, trades memory for desire.

1 – Anne de Staël, ‘Je suis plus byzantin que latin’ in Nicolas de Staël en Provence, (Paris: Éditions Hazan – Culture Espaces, 2018) p. 109

2 – Francesco Alberoni, Le choc amoureux: Recherches sur l’état naissant de l’amour (Paris: Éditons Ramsay, 1981)

3 – A variation on Alberoni’s formulation is the following: ‘Many people “enter passion” during a major disruption in their life: at certain age-related crises, for example, or when a period of intense personal investment in a project comes to an end.’ Marie-José Grihom & Pascal-Henri Keller, ‘La passion: entre aliénation et création’ (Revue française de psychanalyse 2010/4 Vol. 74) pages 1161-1175. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

4 – Henri Bergson in Gilles Deleuze, Bergsonism, tr. Hugh Tomlinson & Barbara Haberjam (NY: Zone Books, 1991) p. 63

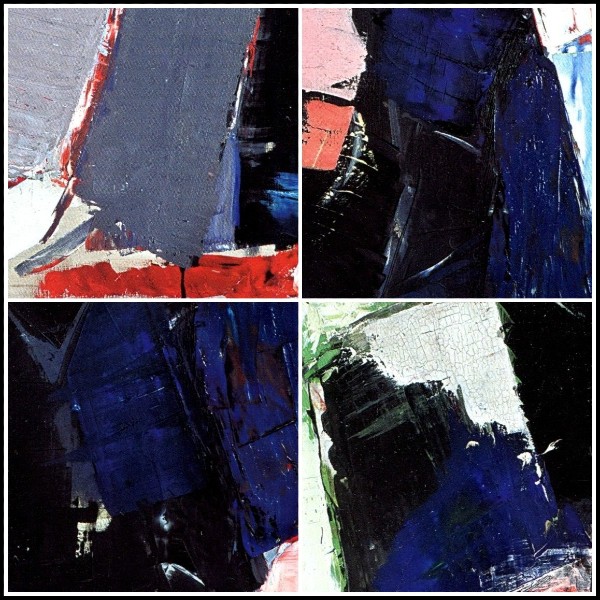

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (4 details)

Anne de Staël: ‘It was at this time [July 1953] that he painted my portrait. I posed in the studio seated on a bar stool. (‘Then again, bum on a bench, she could simply be half-seated’—the right hypothesis! Does it make the others wrong?) At that time I was like a bamboo stem, tall and skinny. He made a sketch that covered the entire surface of the canvas. I noticed that my little life needed a large format (130cm x 90 cm). I did not pose long, I was breathing in shallow breaths. Over the following days he continued to work on the painting, and the more it developed the more I saw he was projecting me into the future. What is a portrait? At that time I didn’t know. By making me look as he imagined me in the future, he had to discern with precision my present being. Once the painting was settled in its metaphor, I could become who I was again: a bamboo stem, tall and skinny. In reality it would take me a very long time to catch up with the painting. Did that mean it did not wait for me? It doesn’t matter. My father saw me as I would never be and as I never was. Cutting corners, it was impatience that made me. Now, I wonder, did I look at the painting often enough while growing up to take inspiration from it?’

And there you have it, dear reader, from Anne de Staël herself.

1 – Anne de Staël, ‘Je suis plus byzantin que latin’ in Nicolas de Staël en Provence, (Paris: Éditions Hazan – Culture Espaces, 2018) p. 109-110

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (4 details)

In April 1954, nine months after painting the portrait and six weeks after Anne’s thirteenth birthday, Nicolas wrote to Jeanne: ‘Anne superb. Startling in her rare beauty. Bearing of a filly not used to its long legs.’1 The poetic intensity of Staël’s apprehension of reality is not given to all fathers, but all fathers of adolescent daughters will be touched by their child’s vulnerability when her body’s development starts outpacing her mind’s. In projecting his filly-like child into a future wherein her resolution endows her with style and vigour, he is expressing, perhaps, a wish that she become a woman in control of her destiny: precisely the capacity he denies Jeanne.* Anne might have been his anchor to a livable reality: his passion was unlivable. Might being together with her on a more sustained basis have helped him? I think it might have. If Nicolas de Staël in his passion was like a dog chasing after its own tail, the adolescent Anne, in the magic of her metamorphosis, might have been able to throw him a bone: a bone that might have been a spanner in the works of passion’s infernal machine.

* Inevitably, of course, for passion admits no obstacle (which is why, in the Romantic tradition, death is its only outcome). Regarding Jeanne Polge, apart from the fact that she died in 20142 and that she was a good friend of Albert Camus3 and his wife Francine4, public information about her is extremely rare5. There is, however, an excellent interview with her son, Jacques Polge6, and also an extract from a letter she wrote to Herta Haussmann: ‘I believed I was going mad. For two weeks I sought relief, but found none in drugs. And then depression came—the big, the enormous hole. We have to react, Herta, following the example of he who suffered so much for me. When I see you I will tell you the whole dreadful story.’7

1 – Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955, p. 554

2 – La Croix (journal, Paris), 11 mai 2014

3 – Olivier Todd, Albert Camus: A Life (NY: Vintage, 1998)

4 – Jacques Polge, interview with Marie du Bouchet in Jérôme Gille, Nicolas de Staël en Provence, (Paris: Éditions Hazan – Culture Espaces, 2018) p. 149-153

5 – For good reason. Jacques Polge, Jeanne’s son: ‘My parents always refused every request to talk about this period. They entrusted me with Nicolas de Staël’s letters to my mother, and it was only after the death of my parents and of Françoise de Staël that they were published. Similarly, it was at that time that a photo of my mother and Nicolas together appeared for the first time. That photo was taken in what we called at the time a ‘dancing’ [dance hall] near Pernes-les-Fontaines [Vaucluse]. (Jacques Polge, interview with Marie du Bouchet)

6 – Ibid

7 – Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955, p. 684

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (4 details)

Anne de Staël today is a poet. A poet, not a versifier, not one who hoodwinks sleepwalkers into believing the abbreviation of prose lines, the sprinkling of ‘picturesque’ words, the use and abuse of rhyme, constitute poetry. Only the illiterate believe that. Instead, Anne’s perception of experience is poetic—she sees through the sediments of culture that obscure reality—and, from the standpoint of a singular consciousness, she conveys that perception verbally. Do you see where I’m leading, dear reader? Do you see that I’m suggesting Anne de Staël does in words exactly what Nicolas de Staël did in paint? Portrait d’Anne, from the perspective of today, is a record of the painter’s past (memory) and the poet’s future (expectation). Anne de Staël : ‘This is not a memory, but an engraving situated at the intersection of poetry and painting, of life and creation, revealed by the color of words and the accents of a palette.’1

1 – Anne de Staël, ‘Je suis plus byzantin que latin’ in Nicolas de Staël en Provence, (Paris: Éditions Hazan – Culture Espaces, 2018) p. 105. This sentence is the opening of her reflections on the family’s time in Provence.

A POEM BY ANNE DE STAËL

Allumer éteint une nuit

La vue coiffe la vision

Le champ profond pivote

Dans une pelle de paupière

Anne de Staël, Le cahier océanique (Brussels: La lettre volée, 2015) p. 122

A TRANSLATION OF THE POEM BY RICHARD JONATHAN

Turning on a light extinguishes a night

Sight obscures vision

The deep field pivots

In the scoop of an eyelid

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (4 details)

Consider this oral account by Anne de Staël of an incident in her childhood:

‘Travelling at night in a van—he had put some paintings in the back—we left Paris, my father, my brothers, my sister and I. In the morning we arrived at Ménerbes. We must have all gone straight to bed. Then, early in the afternoon, my father said to me, ‘Come, you’re going to help me carry the paintings up to the studio’. We went back down to the van, where he passed me a huge painting, bigger than I was, and said: ‘It’s easy to hold because there’s a canvas stretcher behind it; you just have to get a good grip on the stretcher’. It was a day the mistral was blowing. The mistral is a fearsome wind, it can blow you off course—you won’t turn right if it doesn’t want you to turn right. I said to my father: ‘Okay, I’ll carry it up the path’. He walked ahead of me, other paintings in his hands, but as he was very tall and strong, the paintings didn’t seem to be battling the wind. I was just a little girl, however, I had never carried a painting before. The one in my hands seemed a strange object. I said to myself, ‘What a fierce wind!’, but a moment later I was wondering whether the ferocity was the effect of the wind or of the painting itself. I felt the painting was fighting back, that it didn’t want to stay in my hands. I held on tight to the stretcher, I was afraid I would be swept up and blown away. My father, seeing me struggling, shouted out, ‘What the heck are you doing with that painting—it’s not dry!’. I feared that I wouldn’t be able to hold on to it, that it would fly off and end up glued against a wall. So the fact that it wasn’t dry was one more thing I had to contend with… Today, looking back, I can see this experience enabled me to grow up. I can now transpose it into other situations. For example, every time I set out to write a poem, I ask myself what is the wind that’s going to tear it out of my hands? What will make it soar on its own? And that’s how, when I pick up my pen, I know the elements of language I must seek out.’1

1 – Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (transcribed, edited for clarity and concision, and translated from the French by Richard Jonathan)

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (detail)

While the mistral is not blowing through Portrait d’Anne, there is nevertheless a sense of a girl advancing in the face of headwinds (even if she is half-seated). If the mistral incident occurred before the painter set to work on the portrait, there is every chance he had it in mind as he worked. Anne, as we’ve seen, was explicit about the repercussions of the incident for her: ‘Every time I set out to write a poem, I ask myself what is the wind that’s going to tear it out of my hands? What will make it soar on its own?’ That is a lesson she learnt from her father: that the immediacy of perception demands a rendering which respects the integrity of the revelation. That is what Staël meant when he used the expression ‘descendre un tableau’: to bring a vision—landscape, still life, figure—down from the uncorrupted heights, as it were, without corrupting it during the process of expressing it. Portrait d’Anne is ‘un tableau descendu’ that attests to the intermingling of past, present and future in a synoptic portrayal of father and daughter. Here is another poem by Anne de Staël. It says in poetry exactly what I’ve just said in prose.

A POEM BY ANNE DE STAËL

Visage

La face d’une figure

N’est qu’empreinte

Le mordant lâche prise

La morsure prend figure

Elle n’est pas du présent de la dent

Anne de Staël, Le cahier océanique, p. 121

A TRANSLATION OF THE POEM BY RICHARD JONATHAN

Countenance

The face of a figure

Is but an imprint

The jaw lets go

The bite figures a form

It’s time is not that of the tooth

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (detail)

Now consider Anne de Staël’s written account of the ‘mistral incident’.

‘Ménerbes, on a day the mistral was blowing, a mistral so violent that it might not relent for days and days. More than once, once it had abated, a peasant caught up in it will have been found hanged, for want of breath, on the rope of the wind. That day I had to carry a freshly-painted canvas from the van to the studio. I had got a grip on it—it was huge!—thanks to the crossbars of the stretcher. The wind was blowing furiously against the canvas; to take even a single step forward was a struggle. I felt my weight as a child was insufficient to keep the painting from flying away. My father shouted out, ‘Be careful, it’s not dry yet!’. Those words were mostly swept up in the wind, but ‘not dry’ were the ones that had resisted. As I experienced it, I was grappling with the fire of a painting. I was clinging to its back, to the invisible side around which the wind rushed with such force that I feared for the visible side. As children, facing a painting, we would never touch it: the painting kept us at a distance. The depth of the colors active on the surface opened up for us immense fields that allowed us to measure the time it would take to cross them, to retain them, to approach them: a lifetime. We first had to get through the colorless plain to reach the field of color.’1

1 – Anne de Staël, Le cahier océanique, p. 129.

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (detail)

Again, we see how Anne de Staël insists on the dimension of time: ‘The depth of the colors active on the surface opened up for us immense fields that allowed us to measure the time it would take to cross them, to retain them, to approach them: a lifetime.’ In Portrait d’Anne, too, space serves time as portrait and self-portrait take turns coming to the surface (of the painting, of consciousness), as youth and adulthood are overlaid one upon the other. Yves Bonnefoy: ‘Painting contains time in several ways. First, through the process by which a painting impinges on us, or rather recreates itself within us. Our awareness of a work of art evolves in time. In order to coincide utterly with the act of vision, the mind needs time—as it encounters obstacles, interprets, rejects, then repudiates or transcends its rejection; a certain lapse of time is necessary if the painter’s essential proposition is to be resurrected in us, as a way of being to which we eventually give our assent. As Plotinus says of a higher object in his treatise On the Intelligible Beauty, our self-awareness must be surrendered if we are truly to possess the object we wish to see; yet it also must be maintained so that our vision itself can reach fruition. Accordingly, in our apprenticeship to the work we go back and forth endlessly between separation and union, passivity and attentiveness, or waking and dreaming, until we achieve that improbably total experience which would be the fruit of a synthesis of the nocturnal path of dreams and the lucidity of waking life.’1 This is precisely the kind of reading I am proposing for Portrait d’Anne.

1 – Yves Bonnefoy, The Lure and the Truth of Painting: Selected Essays on Art, ed. Richard Stamelman (University of Chicago Press, 1995) p. 44. This excerpt is from chapter 5, ‘Time and the Timeless in Quattrocento Painting’, translated by Michael Sheringham.

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (detail)

Anne de Staël: ‘As I experienced it, I was grappling with the fire of a painting. I was clinging to its back, to the invisible side around which the wind rushed with such force that I feared for the visible side.’ This means exactly what it says. But, since my theme is the father-daughter relation, I’d be remiss if I did not at least mention that it would not go amiss (fancy prose = danger zone!) if I point out that it can also be interpreted as a ripple from the subconscious on the surface of consciousness: Oedipal dynamics are at work, all the more so as the father is in the ‘mid-life crisis’ zone (what the French call ‘le démon de midi’) and the daughter is on the cusp of puberty. The only relevance of this for our discussion is the suggestion that Oedipal dynamics contributed to the tensions in the painting—beyond the play of line, color and shape—that give Portrait d’Anne its alertness, its energy and fluidity, in time and space.

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (detail)

Now what about suicide? There is an abundance of both personal and professional accounts of children traumatized by the suicide of a parent. That Anne de Staël does not fit this mould is, I would argue, yet another example of her affinity with her father, and another argument in favor of interpreting Portrait d’Anne as both a portrait and a self-portrait. ‘Affinity’ does not mean ‘symmetry’, of course. Neither of Nicolas de Staël’s parents committed suicide, though they died when he was but a child. As for his foster parents, when, in defiance of them, he chose art over engineering, they, in effect, ‘died to him’. Despite that, and despite his displacement from Russia to Poland to Belgium to France, despite his demotion from titled aristocrat to stateless person, in the 700 pages of his collected letters you will not find a single word of self-pity. Neither will you find such a word in any of Anne de Staël’s writings. Yet don’t go thinking that Anne de Staël did not undergo a process of losing: had that been the case, she’d never have become the person she is today, that composed person who radiates a vibrant interiority, that adventurous person who cultivates her humanity. Here, for example, is something she wrote in this regard: ‘The distance at which my father kept us since his move to Antibes forced us to develop our ability to interpret, in the dark, the tonality of a sentence in a letter, a word in a phone call, and even the echo of a friend who’d dropped in after a visit with our father. One thing was clear: Either he would come back, or we would take the train and go and see him. But, between the studio and the station, it was as dark as between Antibes and Paris. Growing up became urgent. It was not like a book where you can just skip pages. It was not like when you’re walking and you can break into a run. This imperative—‘fast!’—was a stone dropping to the bottom of a lake while making the surface ring out in alarm,’1

1 – Anne de Staël, ‘Antibes’, in Nicolas de Staël: Un automne, un hiver, Musée Picasso Antibes-Hazan, 2005, p. 49

Nicolas de Staël, château Grimaldi, Antibes, 15 March 1955 (Photo: Dor de la Souchère | Nicolas de Staël, Antibes, 1954-55 (Photo: Georgette Chadourne)

Jérôme & Françoise de Staël, le Castelet, Ménerbes, 1956 (Photo: Lynn Chadwick)

Regarding Nicolas de Staël’s suicide itself, Anne de Staël has always written or spoken about it dispassionately. She refuses to dispossess her father, posthumously, of his freedom and responsibility by, for example, invoking fatal internal or external pressures. Rather than seeing the act as an aberration, she inscribes it into the continuity of his life. Recall John Berger’s statement cited earlier: ‘Good portraits are both prophetic and retrospective’. How does this apply to Portrait d’Anne? Anne de Staël: ‘We took his death not as an abandonment, but, on the contrary, as an invitation, an invaluable ‘presence’ that urged us to find our way, a way along which Wordsworth’s line, “the child is father to the man” echoed in our ears.’1 From adolescence to adulthood, from adulthood to adolescence, Portrait d’Anne moves, and in so doing, it reveals its duality as portrait and self-portrait. ‘Midway on our life’s journey, I found myself / In dark woods, the right road lost. To tell / About those woods is hard—so tangled and rough / And savage that thinking of it now, I feel / The old fear stirring: death is hardly more bitter.’2 Nicolas de Staël ‘entered passion’ in order to get out of the ‘dark woods’, and in so doing he took a detour through adolescence: he fell in love in an adolescent (absolutist) way. Anne speaks of his death as ‘an invaluable presence that urged us to find our way’ (my emphasis), while Nicolas—‘in dark woods, the right road lost’—had lost his way. Yes, Portrait d’Anne is a portrait of an adolescent: the adolescent, however, is not only Anne.

1 – Anne de Staël, ‘Antibes’, in Nicolas de Staël: Un automne, un hiver, Musée Picasso Antibes-Hazan, 2005, p. 50

2 – The Inferno of Dante: A New Verse Translation by Robert Pinsky (NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1997) Canto I page 4

Nicolas de Staël, Antibes, 1954-55 | Photo: Georgette Chadourne

In Portrait d’Anne I see Nicolas de Staël walking, with stoic determination, to encounter his ‘self-willed fate’. Anne de Staël: ‘Nicolas de Staël never stopped painting from the moment he started. He never took a rest. There’s a letter in which he writes that he can’t take it anymore. That, it seems to me, is sufficient argument to understand his suicide.’ And: ‘In a frenzy of creation Staël took his own life. When Jeannine died in 1946, he wrote to her mother: “For my part, I’d be well-content to die in the density of a life such as she lived.” And that, as I see it, is exactly what he did: he died in the intensity of living.’1

1 – Anne de Staël, interview in FloriLettres n°117, Fondation La Poste, septembre 2010

Nicolas de Staël, Antibes, 1954-55 (Photo: Georgette Chadourne) | Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953

What is a face? Levinas, we recall, defined it thus: ‘A face is that which in the other regards me, reminding me, from behind the countenance he puts on in his portrait, of his abandonment, his defenselessness, and his mortality…’ In Portrait d’Anne, in both its portrait and self-portrait aspects, the figure’s forthright attitude conveys a proud solitude: that is ‘the countenance he puts on in his portrait’, that is the phenomenological aspect of both Anne’s and Nicolas’ being-in-the-world: keep calm and carry on; don’t complain, don’t explain. And yet, like a ghost in the machine of resolution, the figure’s ‘abandonment, defenselessness and mortality’ is also apparent, but only in its self-portrait aspect: that is Nicolas de Staël’s vulnerability, that is what primes him for the epiphanies he will translate into paint through the process he called ‘descendre un tableau’. Levinas continues: ‘…and his appeal to my ancient responsibility, as if he were unique in the world, beloved’. That characterizes not only the reciprocal relation between painter and sitter but also that between the viewer and the two of them. Painting, like all forms of art, is an appeal to our ‘ancient responsibility’ to respond to the call of what our senses perceive, to discern the singular (‘unique in the world’) and cherish (‘beloved’) the individual. Once again, we see that Portrait d’Anne, despite not showing a face, functions as one.

Nicolas de Staël, Antibes, 1954-55 (Photo: Georgette Chadourne) | Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953

IV. CONCLUSION

CQFD, as the French say: While in the domain of art nothing can ever be as cut-and-dried as it can be in the realm of science, I believe I have solidly argued my two theses: Portrait d’Anne is both a portrait and a self-portrait; it functions as a face (as defined by Emmanuel Levinas and John Berger) despite the fact that no face is shown in it. Have I convinced you, dear reader? Whether I have or not, if I have stimulated you to look more closely at the magnificent work of Nicolas de Staël, I am content. I welcome your comments via the Comment Box below.*

* Écrivez en français si vous estimez qu’en anglais votre propos serait moins efficace; j’en assurerai la traduction.

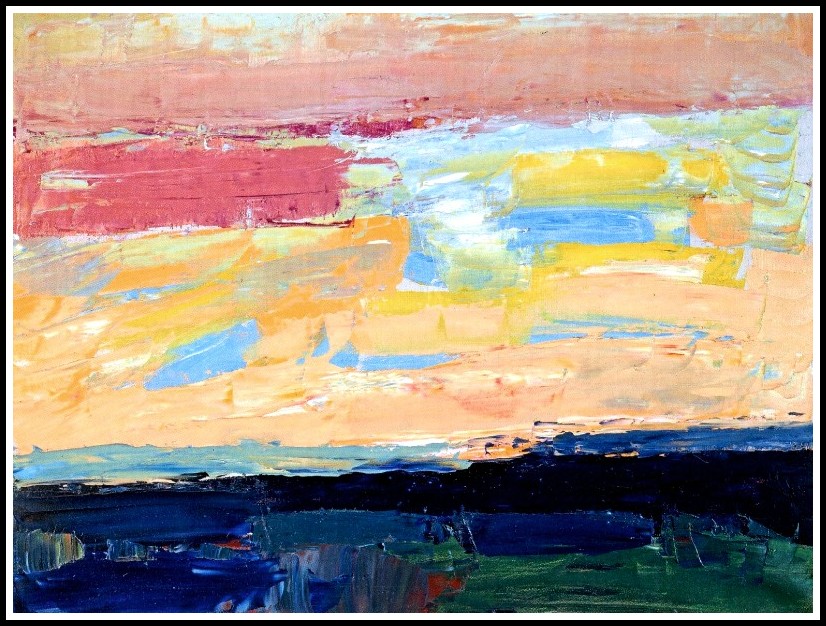

Nicolas de Staël, Marine, 1954

V. CODA

If a touchstone of a true artist is that any one of their works is instantly recognizable as theirs, then Nicolas de Staël, from the moment he found his voice, passes that test. Yet, in the English-speaking world, not a single monograph of his oeuvre has ever been published1, nor has any biography. In French, in contrast, many excellent monographs and exhibition catalogues are available, in addition to a fine biography, various forms of reflective studies, and even an excellent literary novel2. As for English-language histories of twentieth-century art, Nicolas de Staël, if he is mentioned at all, gets, at best, a single paragraph. Why such critical neglect? David Hopkins argues that ‘histories of post-war art have, possibly correctly, disparaged much French abstraction, such as that of the tachiste Georges Mathieu, or Nicolas de Staël, for appearing fussy or “tasteful” alongside, say, Pollock or Rothko’.3 Taste, in the land that vaunts ‘bad taste’, is a liability. As a ravaged Europe submitted to an ascendant America, what chance in the critical stakes did a Chateau d’Yquem Sauternes stand against a steel tank of Coca-Cola syrup? In David Hopkins’ history, a volume in the Oxford History of Art series, Staël is never mentioned again.

1 – Only in 2021 did an English version of the Catalogue raisonné come out, while in the used-book market, two sleepy exhibition catalogues from the 1950s slowly circulate.

2 – Nathalie Chaix, Grand nu orange (Orbe : Bernard Campiche Éditeur, 2012). The novel focuses on the Nicolas de Staël-Jeanne Polge relationship.

3 – David Hopkins, After Modern Art: 1945-2017 (Oxford University Press, 2018) p. 29

Nicolas de Staël, Ciel de Vaucluse, 1953

In the 1989 Phaidon volume, The Story of Modern Art, Norbert Lynton astutely observes that Nicolas de Staël ‘captured for figurative painting qualities of matter and texture and weight that had belonged to abstract painting’ (he also felicitously describes Staël’s paint as ‘at once solemn and luscious’)1. Michael Peppiatt, in his 1988 Art International tribute to Staël, writes: ‘It should be self-evident that no stylistic tags can be applied to an artist as solitary and individualistic as Nicolas de Staël, and also, that one of the glories of his art lies precisely in the way it subverts this kind of classification. But the significance of Staël’s painting as one of the pivots of the mid-century, the point on which essential stylistic decisions were made, still needs to be adequately demonstrated and recognised’.2 In the English-speaking world, that ‘adequate demonstration and recognition’ still has not arrived, as attested to by the strictly French provenance of exhibitions and publications devoted to Staël in recent decades. ‘Money doesn’t talk, it swears’: Auction prices for Staël’s paintings are, however, on the up: In 2018, the New York branch of Christie’s sold Nu debout (1953) for $12,125,000…

1 – Norbert Lynton, The Story of Modern Art, 2nd edition (London: Phaidon, 1989) p.272 & p. 275

2 – Michael Peppiatt, ‘Nicolas de Staël’, Art International 4 (new edition) Autumn 1988. Republished as ‘The Mid-Century Dilemma of Nicolas de Staël’ in Michael Peppiatt, The Making of Modern Art: Selected Writings (Yale University Press, 2020) pp. 173-74.

Nicolas de Staël, Nu debout, 1953

… while in 2019 Christie’s Paris branch sold Parc des Princes (Les grands footballeurs) (1952) for €20,000,000.

Nicolas de Staël, Parc des Princes (Les grands footballeurs), 2ème état, 1952

In an earlier post I put forth the proposition that Nicolas de Staël’s painting shares an affinity with Anton Webern’s music. Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel also shares an affinity with, in particular, the later Staël (1952-1955), as does the moderato cantabile movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 31 in A-flat major, Op. 110. What might be the thread that links the music and the painting?

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage, 1954

Silence. The common thread is silence. So, if Nicolas de Staël, ever since his death in 1955, has been largely ignored in the English-speaking world, might it not be because the silence, the stillness, and the sense of the sacred that characterize his work (in particular the later work) are antithetical to the noise, the busy-ness and the prevalence of the profane that reign in the core of that world? Staël’s (later) paintings are instantanés (as the French say for ‘snapshots’) of things perceived when the veil of the world falls, illuminations glimpsed when a moment of grace offers a vision of reality untainted by ideology. Staël could never be ‘made in America’1: wherever hyperconsumerism reigns, vulgarity rules. Ceci explique cela. Stéphane Lambert, in his book Nicolas de Staël: Le vertige et la foi,2 offers an interesting discussion of what he calls the ‘unwitting complicity’ between Nicolas de Staël and Mark Rothko. And indeed, the quietude and dignity of Rothko’s painting are the polar opposite of the noise and vulgarity that characterize consumerism. An exception that proves the rule?

1 – Nicolas de Staël, New York 1953, to Denys Sutton: ‘Am not made for this country, coming back double-quick to our dear old Europe. Kiss every stone of London for me, I’ll do the same thing in Paris myself.’ (Nicolas de Staël, Lettres 1926–1955, p. 401)

2 –Stéphane Lambert, Nicolas de Staël: Le vertige et la foi (Paris: Arléa, 2015) pp. 141-150.

Nicolas de Staël, Coin d’atelier fond bleu, 1955 | Mark Rothko, No. 61 (Rust and Blue), 1953

I close this essay with a quote from John Berger, a man whose politics I find too dogmatic, but whose sensitivity to the vibrancy of being in every individual has my enduring admiration:

‘Nicolas de Staël was a painter who never stopped searching for the sky. Today he encourages us who are in the circle, the ever renewable circle, of those struggling to find a way out of the present darkness, and who, despite everything, will do so. He encourages us by his courage, and by the unique maps he left behind about crawling towards the light.’1

1 – John Berger, Portraits: John Berger on Artists (London: Verso Books, Kindle Edition, 2021) p. 528. Berger’s essay is compiled from text drawn from two sources: his novel, A Painter of Our Time (1958), pp. 126–27 and his article, ‘The Secret Life of the Painted Sky’, Le Monde Diplomatique, June 2003.

Nicolas de Staël, Ciel de Vaucluse, 1953

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

PART II – JOHN RICHARDSON ON NICOLAS DE STAËL

From John Richardson, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice: Picasso, Provence and Douglas Cooper (UK: Jonathan Cape, 1999) 92-96

Douglas Cooper disliked most of the young recruits to the School of Paris, but there was one exception, a Russian giant who drove a large camper up to our gates one November afternoon in 1953 and sounded his horn. ‘I am Nicolas de Staël’, he announced, ‘and I have an introduction from Denys Sutton [an English critic].’ I let him in, a bit nervously. Although Douglas knew little about Staël, he was apt to dismiss him as just another of ‘those tedious nouvelle vague abstractionists.’ How would the two of them get on? I need not have worried. Staël had been elected to the Czar’s College of Pages at the age of two, and his courtesy was more than a match for Douglas’s truculence. What is more, Staël’s charm turned out to be on the same scale as his frame—manic eagerness tempered with Russian melancholy.

Nicolas de Staël, 1954 | Photo: Denise Colomb

Staël showed such understanding of the paintings on our walls, above all the Braques, that he won Douglas over in a matter of minutes. And then, far from being a hardline abstractionist, Staël turned out to be in the process of making his way back to the figurative path. This ensured an instant entry into Douglas’s good books. For his part, Staël, whose work had just begun to sell, was delighted to have found a new, famously discriminating fan. Over the next two and a half years he would give Douglas and me a fine, small group of his paintings and drawings. Pride of place went to a smashing landscape of Agrigento (1953)—vermilion roofs against a purple sky—which the artist had picked out specially for the ‘château des cubistes’. Hung at the foot of the stairs, it vied with the Léger mural on the landing above.

Nicolas de Staël, Agrigente, 1953

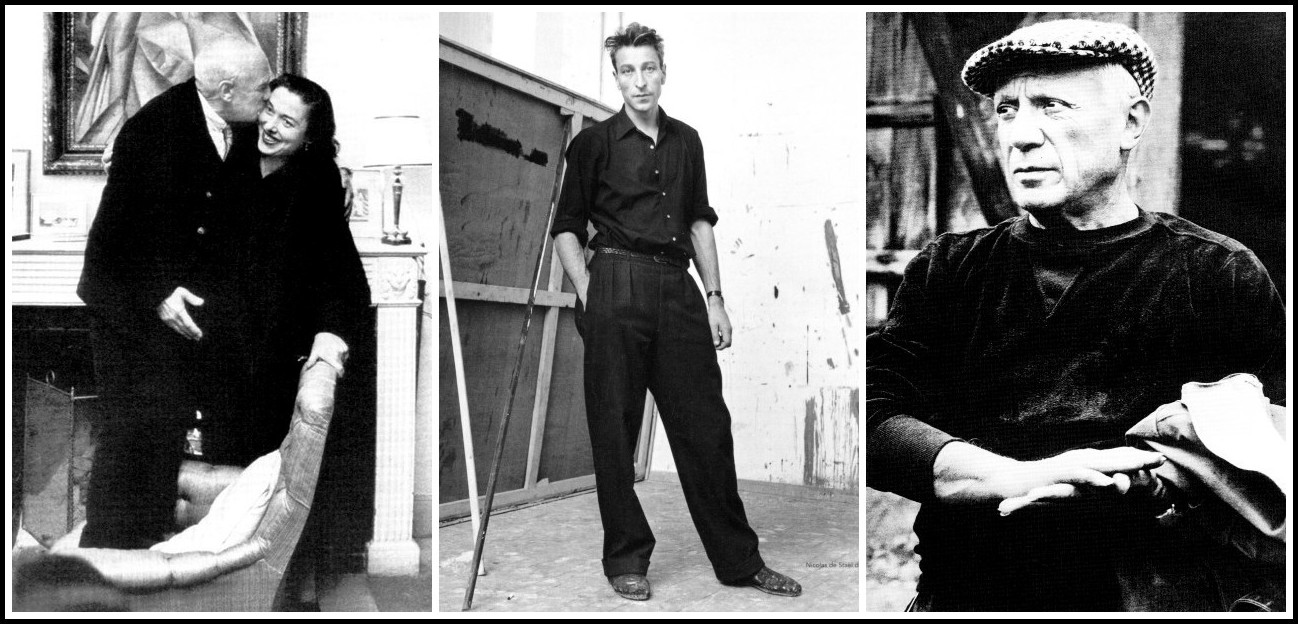

Nicolas became a regular visitor. Douglas and I relished the prodigious way this giant ate and drank and laughed and groaned. He was extremely articulate, not only about painting but also about literature—Henry James in particular—and turned out to have a number of poet friends, among them the celebrated René Char. But Staël’s principal passion was Braque. He regarded himself as Braque’s disciple and had taken a studio around the corner from Braque’s house on the rue du Douanier, so that he could have constant access to him. Just as well he did: one day Nicolas went up to Braque’s top-floor studio and found the frail old painter in the throes of an emphysema attack. He summoned help and saved his life. The affection and respect were reciprocated. To my knowledge, Nicolas was the only young artist Braque spoke of with unqualified enthusiasm: he accepted him as a follower and occasionally subsidized him when money ran out. As for Picasso, Nicolas knew him and greatly admired him—but from afar. He liked to describe their first meeting at a Paris gallery toward the end of the war. Looking up at this giant towering over him, Picasso had felt like a baby. ‘Take me in your arms’, he had said.

PICASSO STANDING ON A CHAIR TO KISS LAURETTA HUGO | NICOLAS DE STAËL, 1954 | PICASSO, 1953

Photos: 1 & 3, John Richardson Collection | 2: Denise Colomb

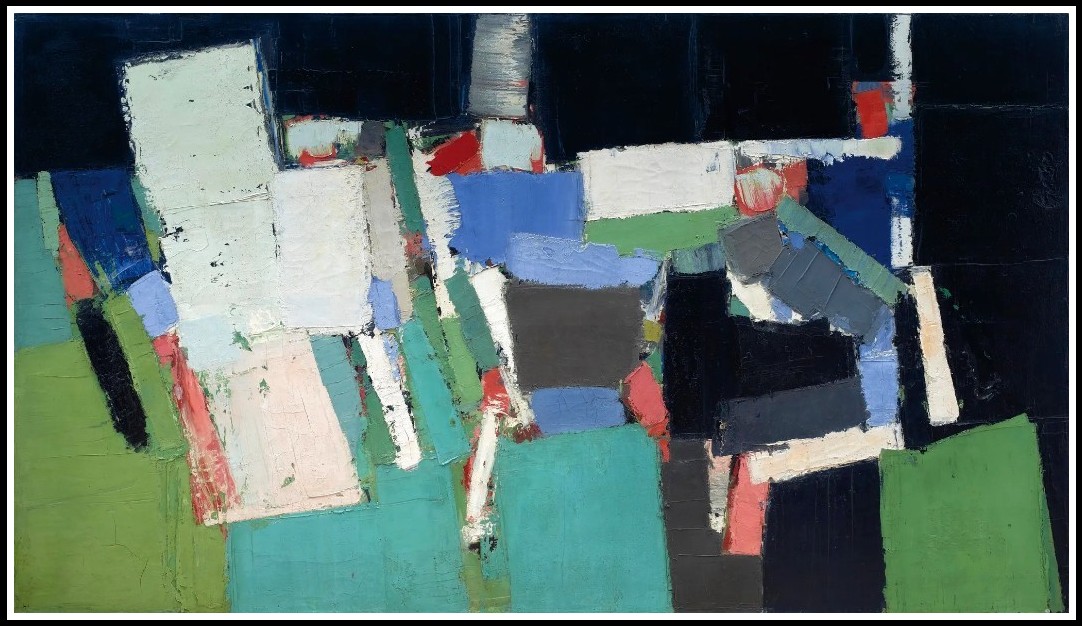

When Nicolas began frequenting Castille, I was writing the first of two books on Braque, and I profited greatly from his practical experience of Braque’s theories of ‘tactile space’ and the interrelationship of color and texture. Nicolas’s exploitation of impasto derived from Braque; so, less obviously, did the flat washes of color and infinite gamut of grays and blacks in his later work. More of a surprise was his obsession with the etchings of that rare and mysterious seventeenth-century Dutch artist, Hercules Seghers, whose prints were the inspiration for some marvelous drawings of boats that he gave us. After dinners at Castille, Nicolas would drive off into the night in the by-now-familiar camper, a kind of traveling studio, which he had filled up earlier that summer with his family and canvases and driven to Sicily—hence our Agrigento painting. On the way back to Ménerbes, he would stop by the roadside and make notes by moonlight. His attention had been caught by ‘the nothingness’ of a particular stretch about two miles down the road from Castille. This was the inspiration for his minimal Road to Uzès landscapes: six irregular segments of thinnish paint in dullish blacks, greens, and grays is all they are, but these segments combine to form a vanishing point, toward which Nicolas, a maniacal driver, seems in my imagination to be forever heading.

Nicolas de Staël, La Route d’Uzès, 1954

In the winter of 1953-54, Douglas and I became regular visitors to Le Castellet, the fortified seventeenth-century house Nicolas had recently acquired at Ménerbes. It crowned one extremity of this hilltop village like the prow of a man-of-war, and in its imposing, fortress-like way it was eminently suited to this scion of the chivalrous Staël von Holsteins. Nicolas had done away with his predecessor’s fustian décor and laid bare the medieval masonry of Le Castellet’s vaulted rooms, which he furnished with a few bits of austere, Escorial-like furniture. ‘The only aristocrat since Delacroix who knows how to paint,’ Douglas said after visiting Le Castellet for the first time. And, true, the fastidiousness and cool Baudelairean dandyism of his style and the panache with which he attacked a canvas did have something aristocratic about it. Thank God for the Revolution, Douglas said. If Nicolas had inherited the family palace on the Nevski Prospect, he would never have been such a great painter.

Le Castelet, Ménerbes, 1954 | Nicolas de Staël’s studio, Le Castelet, Ménerbes (Photo: Art de France, no 1, 1961)

Nicolas was one of the very few modern masters who had actually starved, not so much during his childhood as an orphaned refugee, but during the war, when he was in his late twenties and lived on next to nothing in Nice with a wife who was dying of tuberculosis. Like many another White Russian, Nicolas was too proud and fatalistic to hold his misfortunes against the world. Nevertheless, the scars went deep. As Douglas wrote, ‘He was a complex and in many ways contradictory character: autocratic, exacting, exuberant, morose, charming, witty and uncompromising. He lived out his life between a series of violent extremes. Pride would suddenly be replaced by humility, self-indulgence by asceticism, exaltation by gloom, uproarious laughter by withering scorn, supreme confidence by serious doubts, excessive work by deliberate idleness, great poverty by riches’.

Paris 1944: Nicolas de Staël with daughter Anne & stepson Antek Teslar | 54 rue Nollet, 17ème | Anne, Jeannine & Nicolas

Marcelle Braque put Nicolas’s dilemma in a nutshell: ‘Watch out,’ she told him, ‘you staved off poverty all right, but do you have the strength to stave off riches?’ He did not. This Tolstoyan hero had always been beset by Dostoyevskyan demons, but after his sudden, huge success in America—a sharp-eyed friend of ours, Ed Bragaline, had been so impressed by his first New York show that he had bought several works for himself and persuaded his collector friends to follow suit—the demons got the upper hand. Money enabled Nicolas to indulge his Russian largesse to the full, but there was a certain desperation to his extravagance. One winter evening when he was on his own at Ménerbes, he invited Douglas and me to dinner. To start with, there was a great slab of foie gras. Then came a large turkey, which Nicolas had stuffed with a kilo of truffles. The three of us washed this down with most of a case of Cheval Blanc.

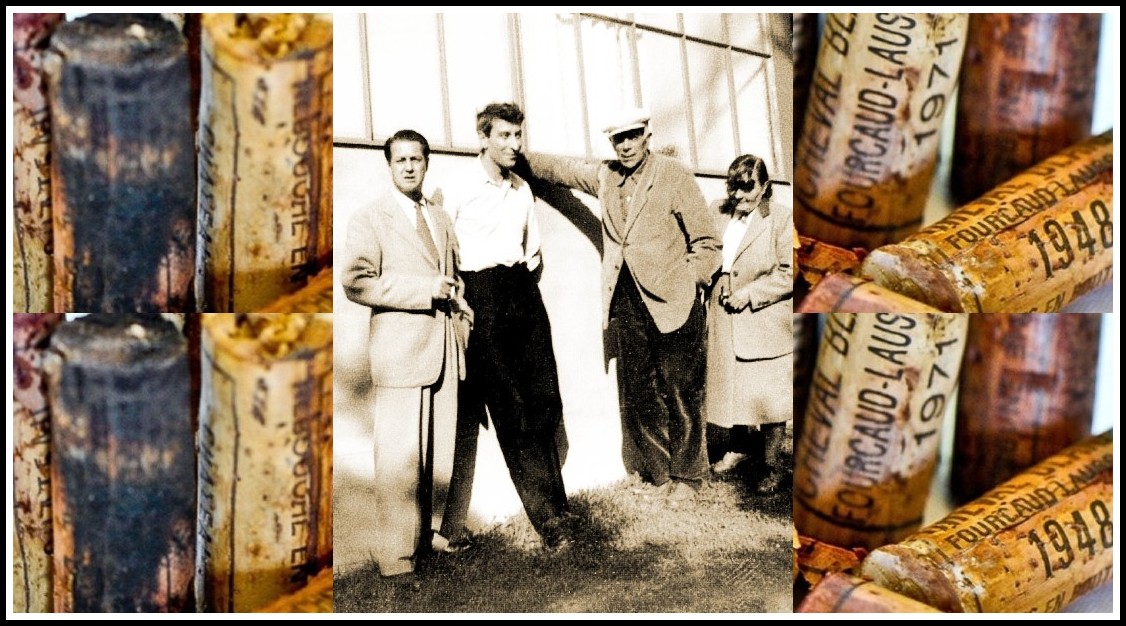

Theodore Schempp, Nicolas de Staël, Georges & Marcelle Braque, 1949 | Cheval Blanc corks

In the fall of 1954, Nicolas left Ménerbes. He had become infatuated with a young married woman called Jeanne—a protégée of the poet René Char. According to Nicolas, Jeanne was prepared to have an affair with him, but was not ready to leave her husband or show her lover much in the way of affection. When Nicolas dined with us on New Year’s Eve, he described the hellishness of his situation. He adored his wife and family, but could not live with them; he resented his recalcitrant mistress, but could not live without her. Meanwhile, he had taken an apartment on the ramparts at Antibes, and was experimenting with a fresh, more figurative approach to a whole new range of subjects. Besides being tormented by chagrin d’amour, he was tormented by doubts about the new direction his work was taking.

Nicolas & Jérôme, 1949 | Nicolas de Staël, Nude Study, 1952-53 | With wife Françoise & son Jérôme, 1950

Toward the end of February 1955, Douglas and I drove over to Antibes for lunch. Nicolas was in the depths of despair, and no wonder. The apartment looked across at Vauban’s sullen-looking fort, which reminded him of the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul that his father had governed. It might have had a certain charm in summer, but on this dismal winter day the gray waves crashing onto gray rocks under a gray sky intensified the melancholy. ‘The noise of the waves is driving me mad,’ Nicolas groaned.

Nicolas de Staël, Le Fort carré d’Antibes, 1955

And yet he had come up with some of the most exhilarating work of his career. Never had he laid on his color more luxuriantly and sensuously than in that mysterious paean to painting, The Blue Studio, which I would come to see as Nicolas’s farewell to art and life. Subject and medium seem to fuse into each other, as in Braque’s work. Douglas could not adapt himself to this sudden leap ahead, and this made him cross and critical. ‘It’s all gone so soft,’ he said, evidently blind to the beauty and originality of the new paintings. Nicolas, who was in desperate need of reassurance, remonstrated with Douglas for his severity. I did my best to lower the tension by praising their symphonic sweep and orchestral color, but Douglas would not desist.

Nicolas de Staël: Atelier fond orangé, 1955 | Coin d’atelier fond bleu, 1955 | Coin d’atelier à Antibes, 1954

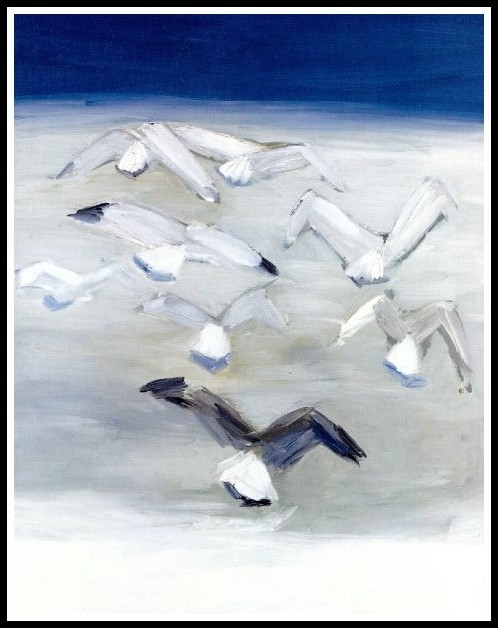

I left them at it and went over to study a canvas that seemed the very essence of anguish: a vast, fearsome painting of seagulls flapping over tossing waves. On the same wall a window gave out onto an identical scene of gulls, grayness, and gloom.

Nicolas de Staël, Mouettes, 1955

Just like the crows in van Gogh’s ominous cornfield, I remember thinking. In retrospect, it is easy to see that this painting was a cry for help. Why didn’t we respond to it?

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield with Crows, 1890

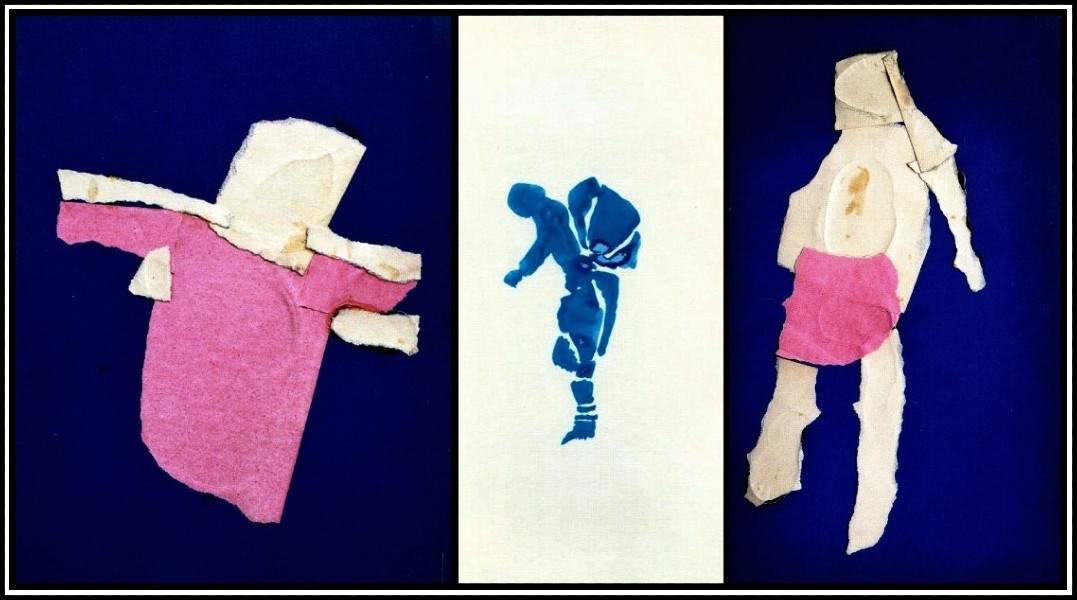

Three weeks later, on the evening of March 16, Nicolas threw himself headfirst off his terrace, and landed just short of the rocks below. He died instantly. He was forty-two, and had barely begun to exploit his new-found lyricism. A few months before his suicide, he had sent me a bundle of collages to choose from: figures, still lifes, and a bullfight made of torn-up colored paper. I had not decided which ones to keep. Now that Nicolas was dead, Douglas suggested I hand all of them over to him ‘for safe keeping.’ Safekeeping indeed! I never got them back. After I left Castille, he used them to make swaps with dealers.

Nicolas de Staël: Personnage, 1954 | Un Porteur, 1953 | Figure, 1954

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

PAINTING IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

CLICK ON AN IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments

1 thought on “Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne: Interpretation”

Bonjour, votre analyse est tout à fait intéressante et avec de nombreuses références à des auteurs anglo-saxons que nous connaissons peu en France. Alors peut-être serez vous intéressé par notre livre “Jeanne ou le réel” qui, si il est un essai sur la peinture de Nicolas de Staël, apporte de nombreuses informations documentées sur Jeanne Polge et son influence fondamentale sur l’évolution de la peinture de Nicolas de Staël durant les dix-huit derniers mois de sa vie. Réf: Philippe Rassat et Pierre Truchot, “Jeanne ou le réel, essai sur Nicolas de Staël” (Edition l’Harmattan, Paris, 2023)