The Promises of a Face

EDOUARD MANET & BERTHE MORISOT: THE FAMILY ROMANCE – PART 1

Nancy Locke

Nancy Locke is Professor of Art History & Director of Graduate Studies in Art History, Penn State University.

From Nancy Locke, Manet and the Family Romance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996) pp. 147-160

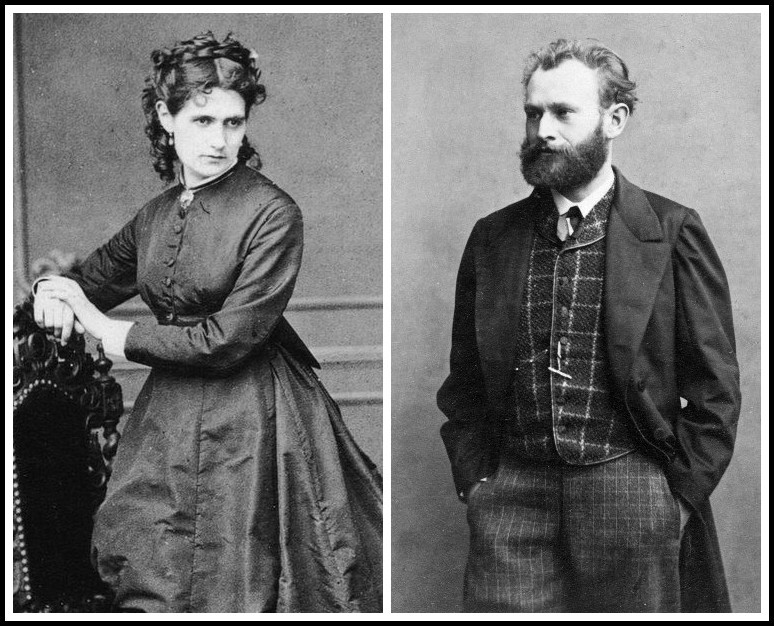

Berthe Morisot | Édouard Manet

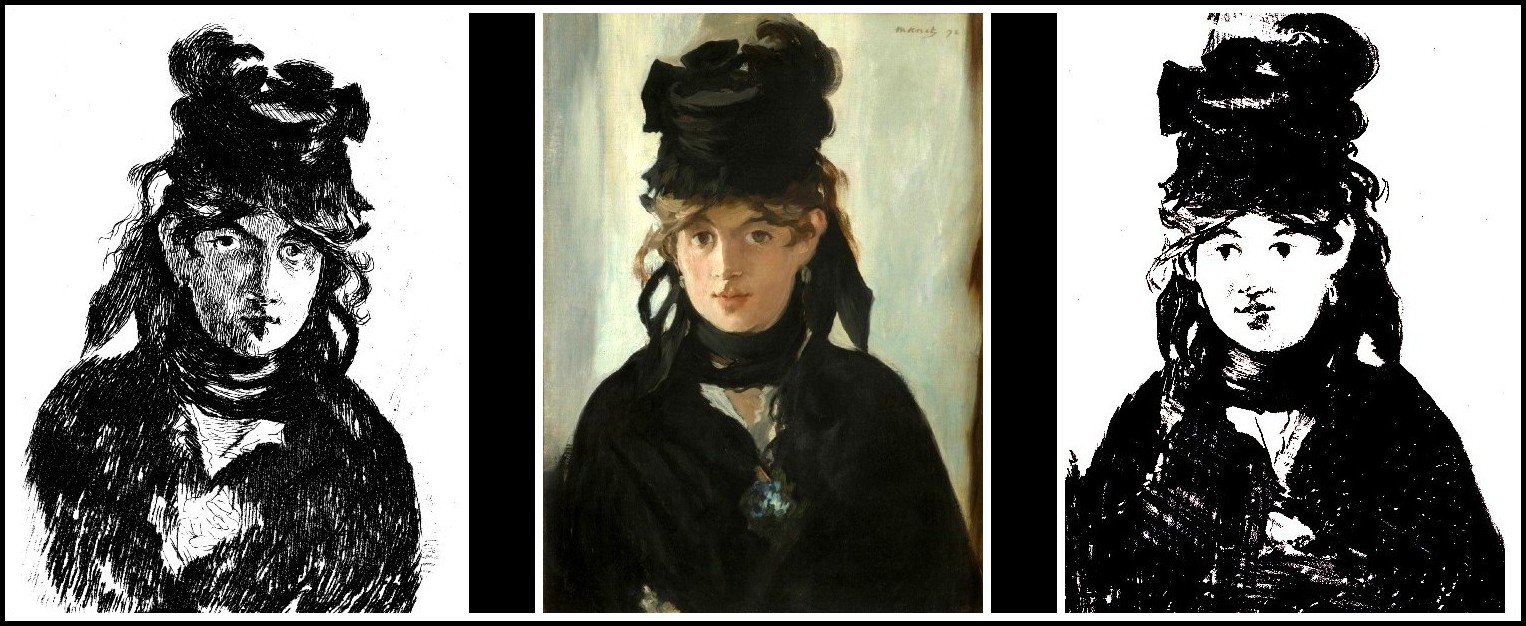

Manet executed an etching and a lithograph of the artist Berthe Morisot, both apparently after the oil on canvas portrait with violets of 1872. While a friend and I were looking at examples of the prints, she made a provocative suggestion—somewhat casually but also in seriousness. She ventured that Manet’s etching portrayed Morisot with a look reminiscent of a self-portrait. What she meant, as she drew on her art-school background to explain, was that during the painting of a self-portrait, as one looks in the mirror, it finally becomes necessary to contrive the symmetry of the eyes, as it is nearly impossible to fix one’s gaze on both eyes. Manet’s Morisot, she said, has that look.

Etching, 1872 | Manet, Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, 1872 | Lithograph (1872-74)

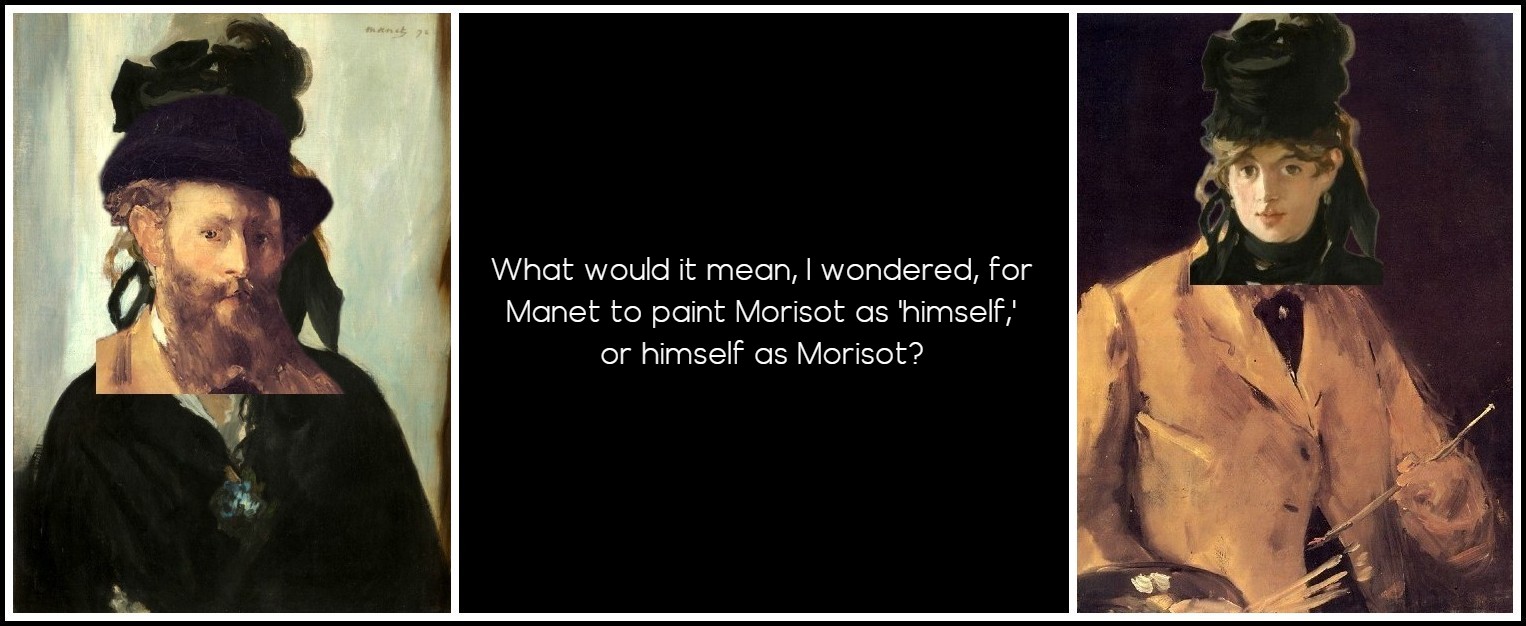

What would it mean, I wondered, for Manet to paint Morisot as ‘himself,’ or himself as Morisot? How and why would a (male) painter in Manet’s position at that point in his career even think of investing portrayals of her with a degree of ‘self’? The idea fascinated me insofar as it appeared to go against some assumptions underlying more recent scholarly re-examinations of Morisot’s life and relationship with Manet. These reappraisals have variously hailed Manet’s portraits of Morisot as ‘entirely generated by her presence,’ ‘entirely devoted to her—her person, her moods, her eyes, her hair, her clothing.’ In other words, they try (too hard) to activate Morisot’s role in creating Manet’s portrayals of her; that is, when they have not castigated Manet’s choice to present her ‘as a well-brought-up young woman sitting inactively, not engaged in work,’ or his attempt to ‘eroticize’ Morisot; that is, when they have not overplayed the idea that Manet was the ‘active’ male painter and Morisot the passive female object, never represented as a working artist in Manet’s canvases.

MORISOT AS MANET | MANET AS MORISOT

Manet, Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, 1872 | Manet, Portrait of the Artist (Manet with Palette), 1879

Several things can be said, first off, about Manet’s portraits of Morisot as a group. They cluster during a period of work that was surely the most uneven in Manet’s oeuvre in terms of sheer output, the years from 1868 to 1874, punctuated as those years were by the Siege of Paris, the Franco-Prussian War, and the aftermath of the Commune. Of the dozen or so pictures of Morisot, only two are Salon-sized: The Balcony and Le Repos; the others scarcely exceed two feet on a side. The titles of the others sound more as if they have been clipped from the newspaper society pages: Berthe Morisot with a Muff, Berthe Morisot in a Veil, Berthe Morisot in Pink Slippers; the list continues like a chronicle of fashion. It seems surprising that these pictures actually outnumber the representations of Victorine Meurent; yet unlike those breakthrough paintings of the early 1860s, (and in fact, unlike the society pages), their appeal as a series derives from their private character.

MANET

Berthe Morisot in a Veil, 1872 | Berthe Morisot in Pink Slippers, 1872 | Berthe Morisot with a Muff, 1868-69

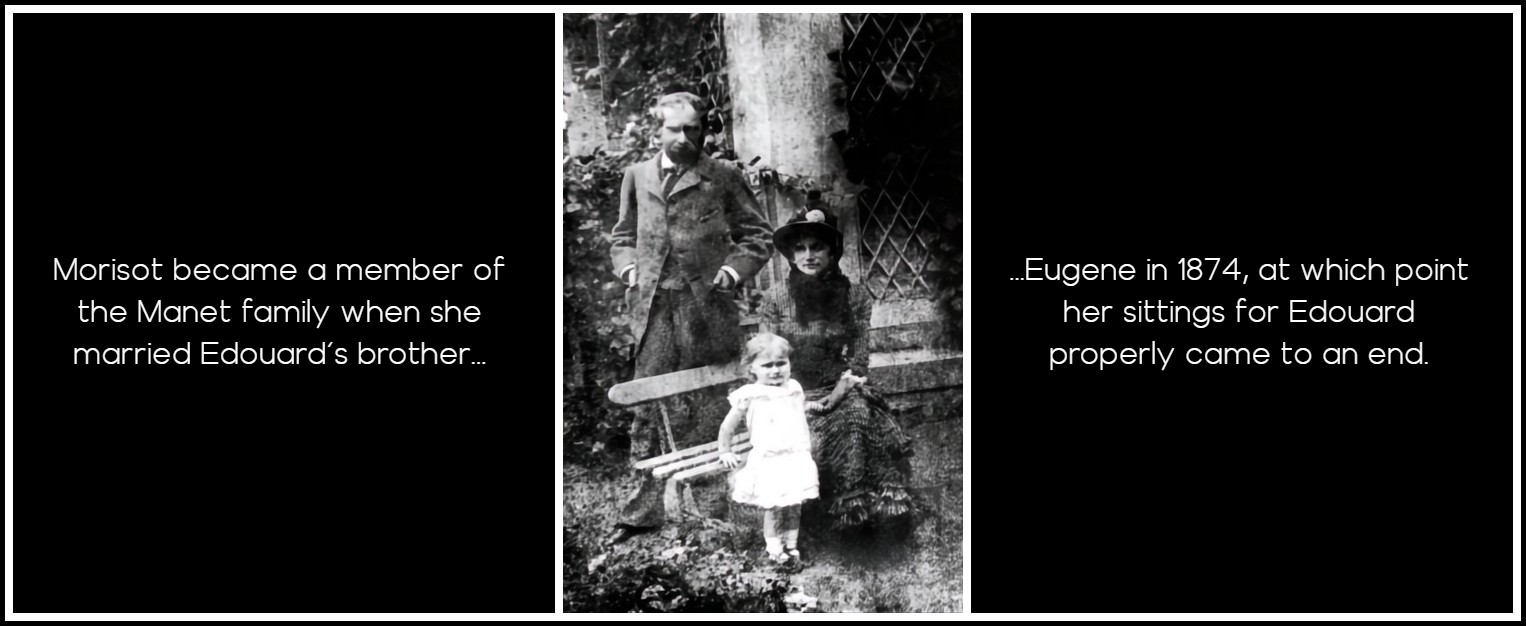

The series of Morisot pictures poses questions unlike Manet’s series of Meurent canvases and his portrayals of Leon Leenhoff. Whereas Leenhoff’s familial identity was deliberately ambiguous, and Victorine Meurent usually wore a costume or acted a role, Morisot always appeared as herself. Although Manet apparently painted only one portrait of Victorine Meurent, and although all eighteen or so Leenhoff pictures are properly understood as genre or modern-life paintings, all the paintings of Morisot—even The Balcony and Le Repos—can be seen as portraits. And the question of ‘familial’ identity must be posed somewhat differently, since Morisot became a member of the Manet family when she married Édouard’s brother Eugène in 1874, at which point her sittings for Édouard properly came to an end.

Eugène Manet, Berthe Morisot, & daughter Julie at Bourgival (Île-de-France), 1880

Manet met Berthe Morisot, so it appears, through Henri Fantin-Latour in 1868. Just as Manet dove into a campaign of paintings of Victorine Meurent in 1862, so too did the artist pursue a series of at least four paintings of Morisot, including the two large ones, in that year and into the next. Commentators have remarked on the renewed vigor that spurred Manet to work after Morisot became a friend and model, and Eva Gonzales a pupil at the same moment, a situation that sometimes irritated Morisot.

Manet, Eva Gonzalèz, 1870 | Eva Gonzalèz, BnF | Berthe Morisot, Self-Portrait, 1885

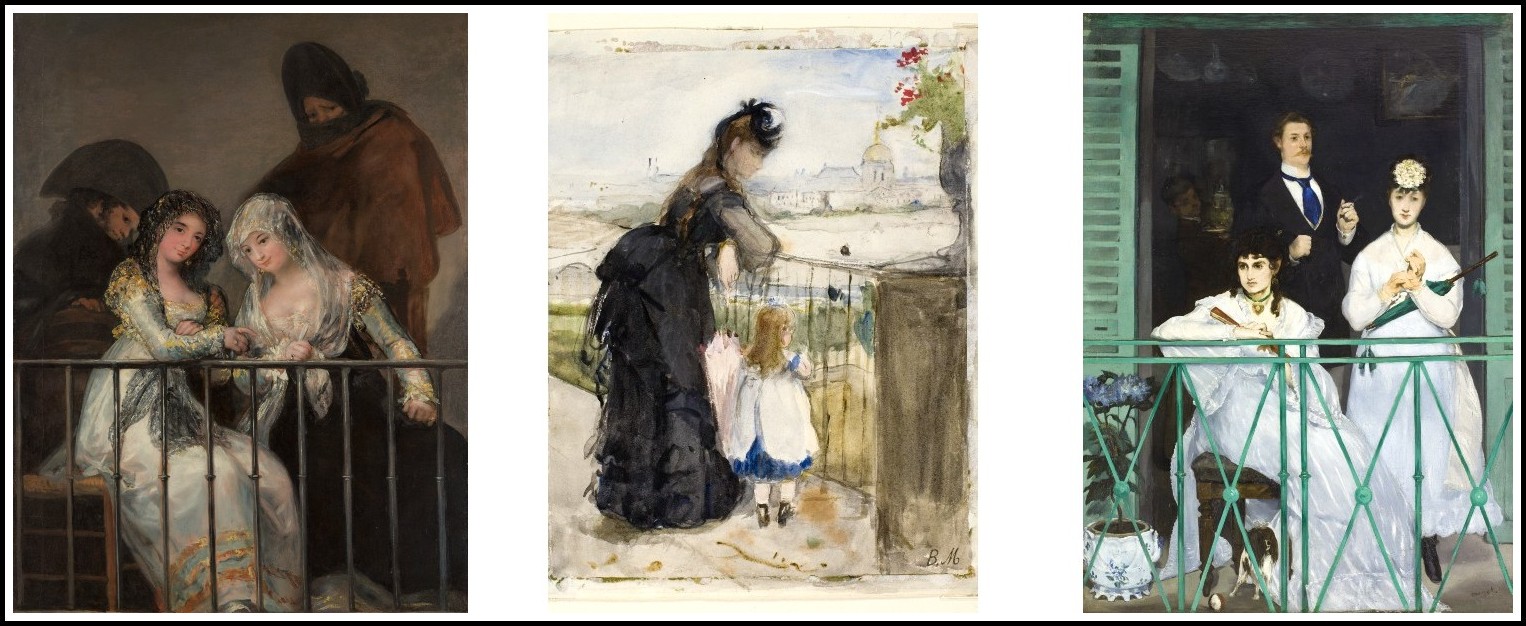

Like his early conceit for Victorine Meurent, Manet’s first plan to represent Berthe Morisot featured her in another ‘party of four’—this one not on the grass but in a more urban setting. According to Tabarant, Manet sought her opinion on his compositional idea before securing her as a model, and her mother chaperoned her sittings in Manet’s studio. In The Balcony, three friends—the painter Antoine Guillemet, Morisot, and musician Fanny Claus—pose in the main area of a shuttered, railed balcony, while Leon Leenhoff appears with a serving tray in the dark interior. As has been well established, the picture is in part a reworking of Goya’s Majas on a Balcony, known firsthand or through an engraving in Charles Yriarte’s 1867 monograph. Yet the use of shutters, doorways, ledges, and windows is more prevalent in Manet’s work than this one reference to Goya would suggest.

Manet, The Balcony, 1869 (detail) | Goya, Majas on a Balcony, 1810 (detail)

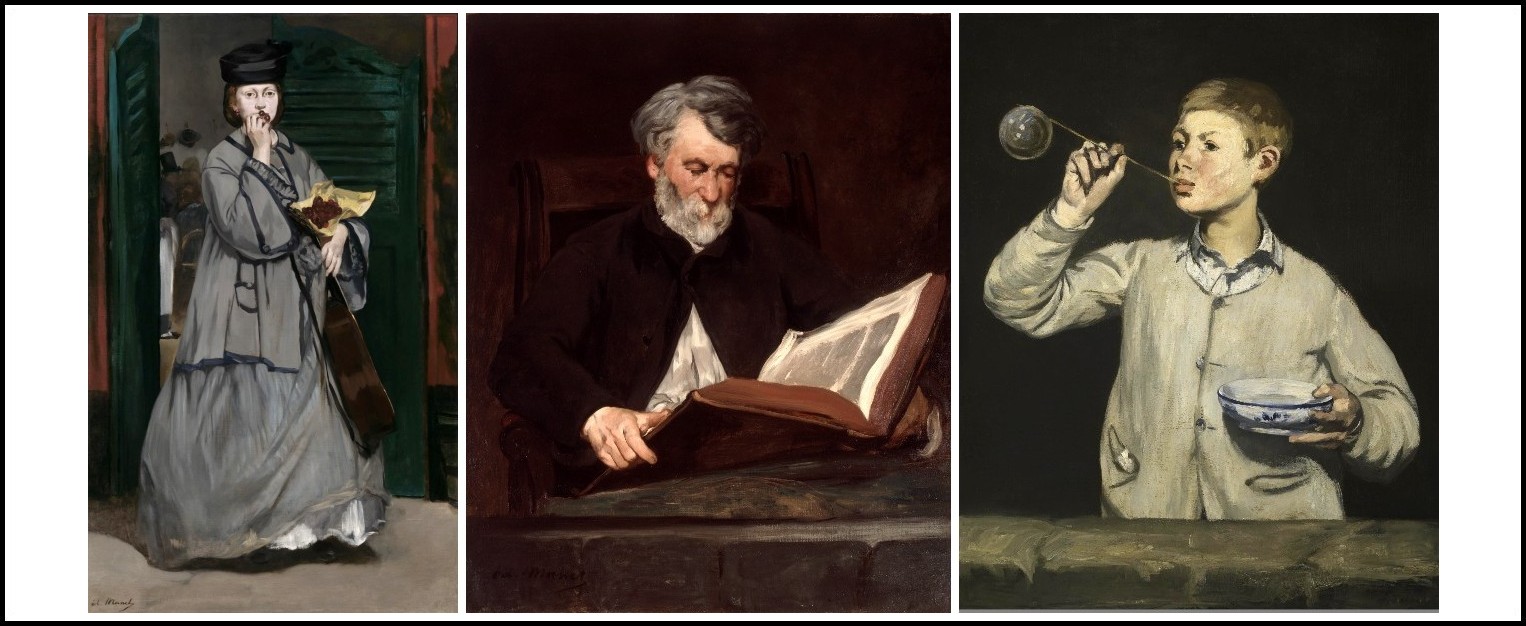

The Absinthe Drinker stands in front of and leans on a ledge which is discontinuous from one side to the other, and which is ambiguously placed in space. Boy with Cherries, as if in a rather crude imitation of Jean Siméon Chardin’s Soap Bubbles, leans over a ledge.

Jean Siméon Chardin, Soap Bubbles, 1734 | Manet, The Absinthe Drinker, 1859 | Manet, Boy with Cherries, 1858

The Reader likewise appears as if seen through a street-level window, with the cracked horizontal band of stone ledge deliberately obstructing a view of the reader’s desk or table. The Street Singer moves through a pair of green shutter-doors, possibly based on those of Manet’s own studio on the rue Guyot. In another picture based on Chardin, Leon Leenhoff appears behind a ledge in Boy Blowing Soap Bubbles. These pictures all attempt to position the viewer vis-à-vis the model in the picture. They evoke the Paris street, the glimpse of a figure in a window or doorway. As modern reworkings of older genre scenes, the compositions also respond to the rectangular shape of the canvas. The slightly askew ledge in the Soap Bubbles picture, for instance, both adds a sense of depth and establishes a slight tension with the rectangularity of the canvas support.

MANET

The Street Singer, 1862 | The Reader, 1861 | Boy Blowing Bubbles, 1867

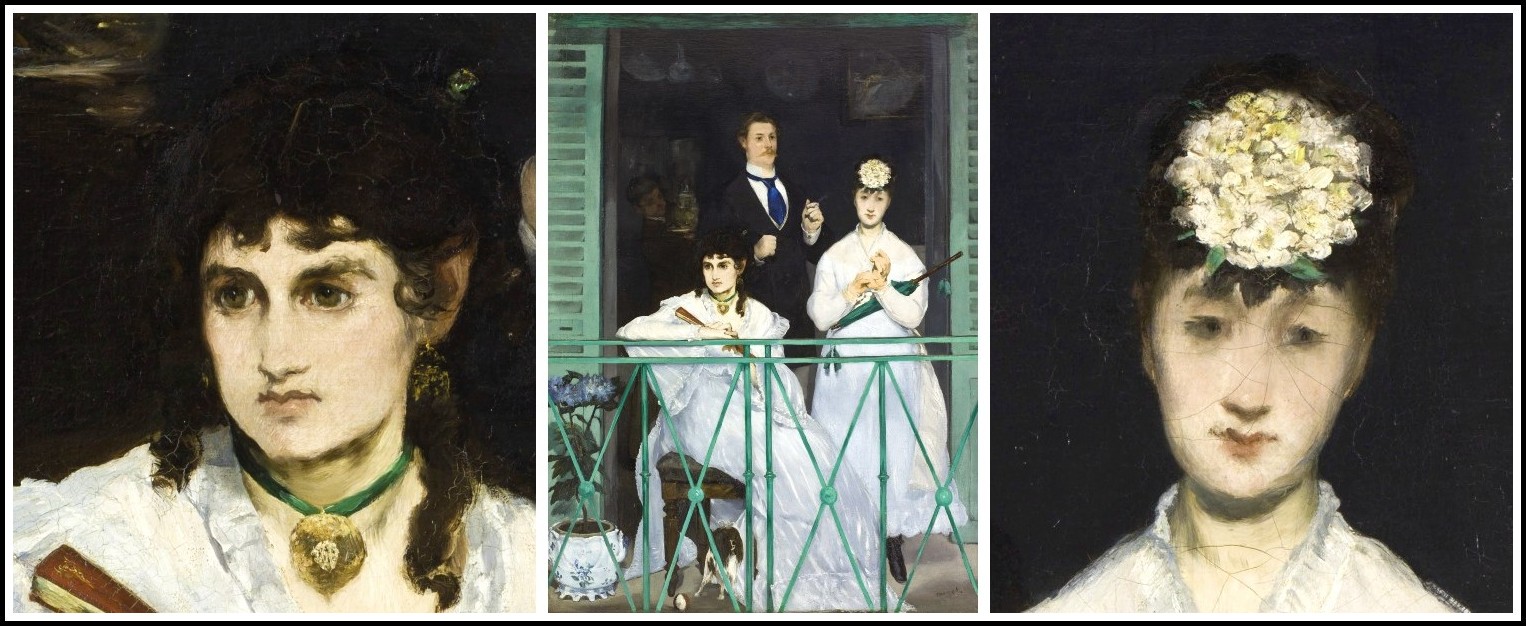

The Balcony, like all these pictures, is a view into a window or doorway, this time into Manet’s summer studio in Boulogne-sur-Mer. Moreau-Nélaton notes that it was the first picture conceived in Boulogne after Manet’s return from London. It draws on the importance of the window as a framing device in the other pictures; yet it is also fundamentally different. There is certainly an aspect of the painting that asks the viewer to see the three friends of Manet as ‘gens du monde a la fenêtre,’ with their fashionable clothing and accessories, and I have pointed out the significance of the fact that Leon Leenhoff does not appear with them on the balcony. Yet there is a sense in which, once again, the individual gazes of the threesome remain separate and discrete; they may be gens du monde but they do not come together to constitute a subset of le monde. And the most overpowering gaze of all, the look that acts as the picture’s fulcrum, is Berthe Morisot’s. It is evident from even a cursory examination of the physical canvas that Manet heavily reworked the head of Morisot. It is her gaze that takes in the view that includes the spectator—whether standing in a street, near the ocean, or on some neighboring balcony. Of course, Fanny Claus also gazes in the general direction of the spectator. Yet her gaze projects almost no concentration; she seems absentminded rather than rapt in thought. Morisot’s gaze, by contrast, is so concentrated as to lose itself, to lose the self-consciousness that absorbs nearly all of Manet’s figures. It is the gaze of an artist rather than a model, a subject rather than an object. The perpendicular lines of the balcony railing and shutters, rather than framing Morisot for the viewer, seem to allow Morisot to frame the world at which she gazes.

Manet, The Balcony, 1869

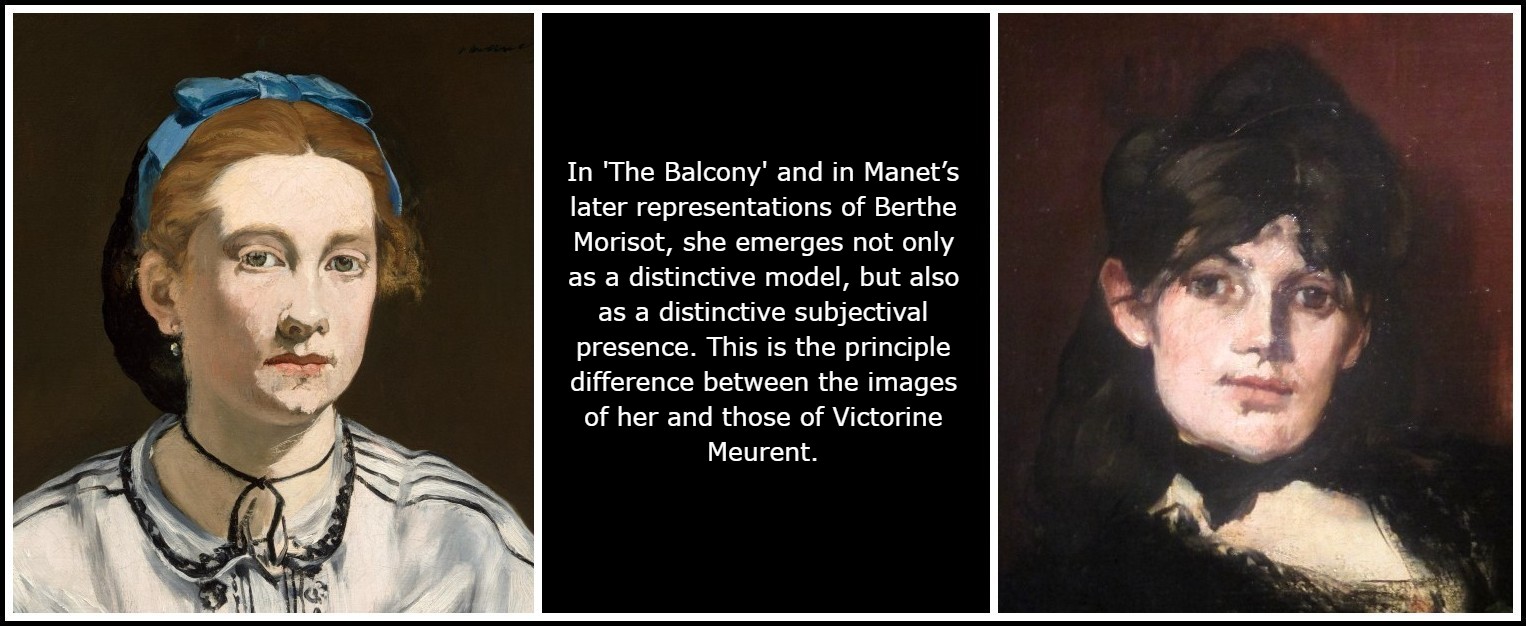

This last point may strike some readers as spurious. After all, is Antoine Guillemet not also standing poised with a cigarette, as if surveying his own canvas in progress? And Fanny Claus tucks her umbrella in the crook of her arm just the way the violist (as she was) holds the instrument during a pause in practice. I am not trying to claim that all three artist friends somehow emblematize their arts while being fashionable gens du monde at the same time. What interests me, rather, is that even in an oeuvre filled with as many memorable gazes as Manet’s, the gaze of Morisot in this picture stands out as particular, and distinct. In The Balcony and in Manet’s later representations of Berthe Morisot, she emerges not only as a distinctive model, but also as a distinctive subjectival presence. This is the principle difference between the images of her and those of Victorine Meurent. I would like to argue that in representing Morisot, Manet explored the very nature of subject-hood, of what might constitute ‘self’ and ‘other.’

Manet, Portrait of Victorine Meurent, 1862 | Manet, Berthe Morisot Reclining, 1873 (detail)

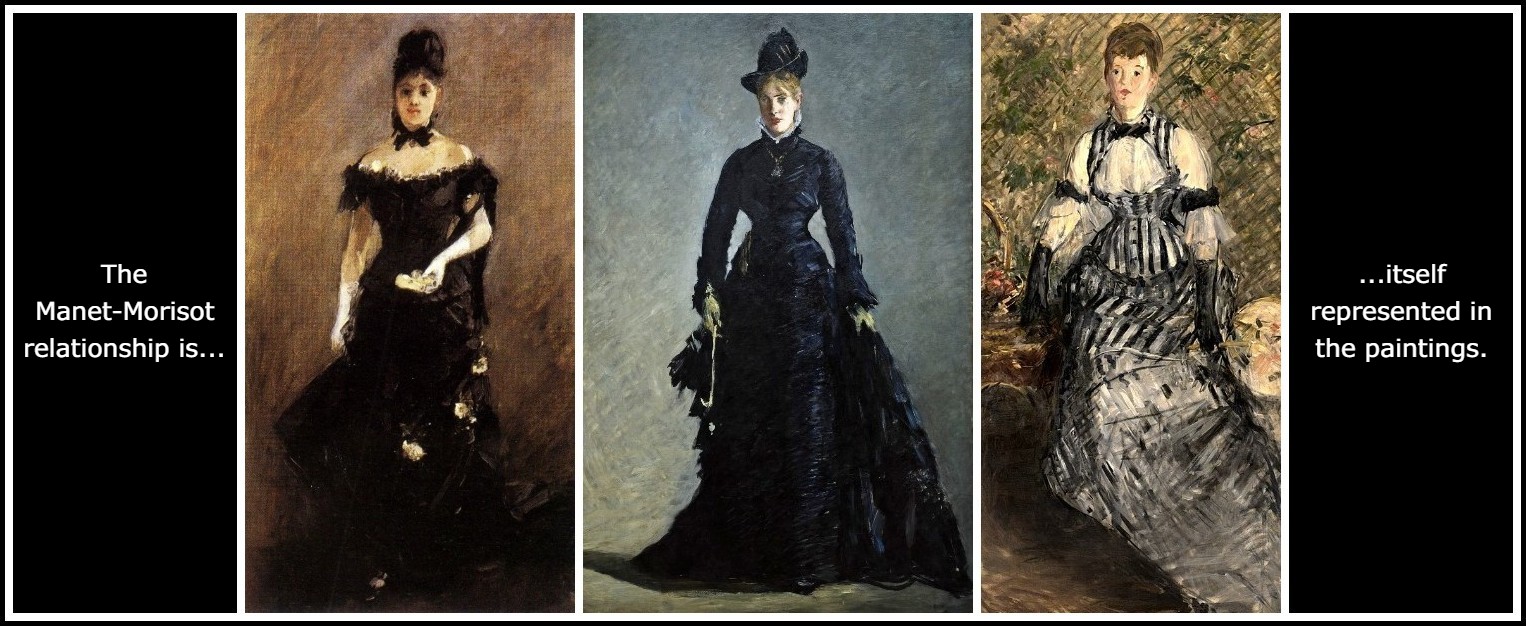

Several writers have commented upon the gulf that separates the series of paintings of Victorine Meurent, paid model and lower-class woman, from those of Berthe Morisot, who was basically Manet’s social equal. Most have noted that since Morisot neither commissioned a portrait nor would have dreamt of receiving payment for modeling services, certain restrictions circumscribed the paintings of her (Mme Morisot’s presence as chaperone being just one). It is true that by paying Victorine Meurent, Manet also had license to ask her to pose in the nude, in male costume, and in whatever else he fancied (his mother’s jewelry); by contrast, by not being able to treat Berthe Morisot as a paid model, he would have been limited to the poses, costumes, and accessories deemed acceptable for a proper woman of her social standing. The actual social and marital status of both Morisot and Manet, then, remain imprinted on the portraits of her; they remain inescapable circumstances of production—something that cannot be said of Manet’s other models and series. Many writers have recognized this and have veered onto the biographical track in writing about how the Manet-Morisot relationship was somehow itself represented in the paintings.

Morisot, Before the Theater, 1875-76 | Manet, Parisienne (Ellen Andrée), 1875 | Manet, Woman in an Evening Dress, 1878

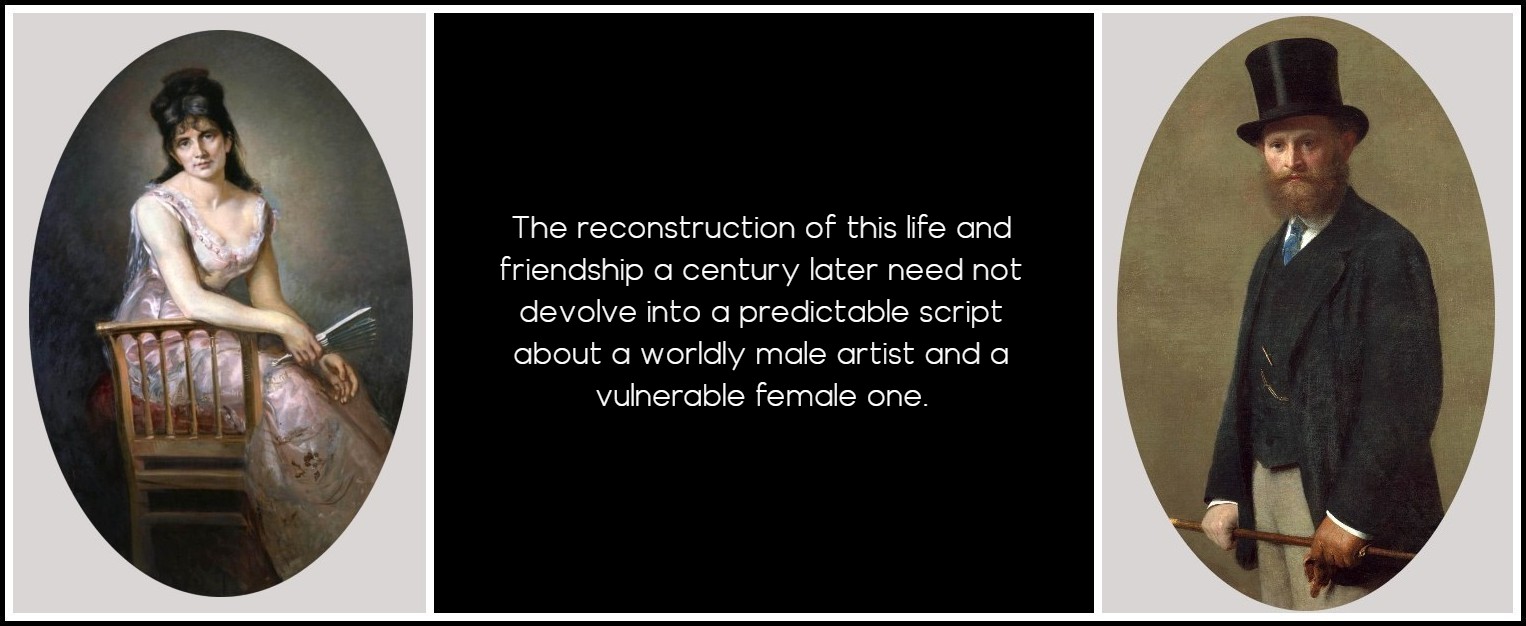

In examining the portraits, then, the historian enjoys at least some license to look to biography but must also, of course, turn to the history of etiquette and to the history of women in the nineteenth century. Fashions in fans and veils, and dictates about the proper attire for mourning, will certainly have a place in any historical account of these paintings. As today’s viewer looks back at nineteenth-century women and men, however, it is perhaps worth pointing out certain things. There is no doubt that as an upper-class woman in the nineteenth century, Berthe Morisot faced restrictions on her comportment and obstacles in the way of her artistic ambitions. Her accomplishments are all the more remarkable in this context. Yet the reconstruction of this life and friendship a century later need not devolve into a predictable script about a worldly male artist and a vulnerable female one.

Marcello, Portrait of Berthe Morisot, 1875 | Henri Fantin-Latour, Portrait of Édouard Manet, 1867

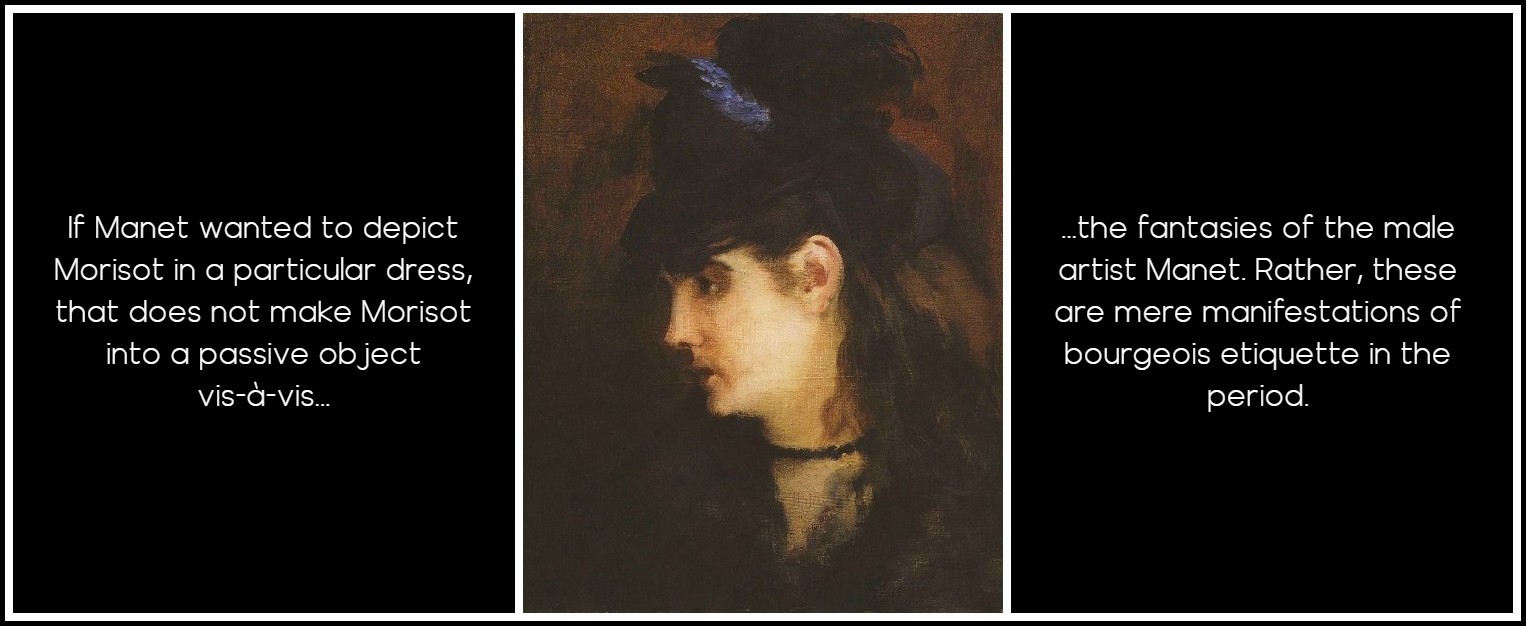

As we approach Manet’s representations of Morisot and his friendship with her, I think it important to remember that a nineteenth-century woman’s imagination did not face the same restrictions as her career or movements. An analogy might help illustrate my point. Many married persons today, female or male, might choose to hold marriage vows above fleeting attractions. The fact of being married might prevent them from acting on some interest or desire, but it in no way keeps their imaginations from being fired by that attraction. The strictures surrounding the proper nineteenth-century woman’s behavior might be manifold, but the principle is the same. If Manet wanted to depict Morisot in a particular dress, or if her mother supervised her sittings in the artist’s studio, that does not make Morisot into a passive object vis-a-vis the fantasies of the male artist Manet; rather, these are mere manifestations of bourgeois etiquette in the period. Morisot’s intelligence and desires remained her own. It is essential that the modern historian not lose sight of that and unwittingly handicap Morisot in hindsight by not granting her the imaginative autonomy that properly belongs to all persons, and certainly to artists.

Manet, Portrait of Berthe Morisot, 1869

Recent biographies of Manet and of Morisot have not been able to deduce much more about the actual relationship of the two artists than had long been known to readers of the little surviving correspondence and to viewers of Manet’s paintings. No evidence of whether their relationship went beyond great mutual admiration, real friendship, and obvious romantic if not erotic interest has emerged. Yet as the relationship has been examined more closely, not only by the biographers but by scholars of the paintings, it has only become more apparent that the aforementioned qualities of admiration, friendship, and interest were truly intense in spite of Manet’s marital status. In 1869, for instance, we find Berthe Morisot anxiously contemplating Manet’s every gesture in her direction; bouts of melancholia, difficulties in painting, and a period of eating disorders all seem clearly connected to her keen interest in Manet and the frustrations of what she called her ‘impossible’ situation. When Morisot married Manet’s brother Eugene in 1874, she described her choice as a kind of compromise, ending the years of living by ‘chimeras’ with a reasonable, practical decision. It is quite evident that the decision to marry Eugene came with the realization that her feelings for Édouard had no future.

Berthe Morisot, Eugene Manet on the Isle of Wight, 1875

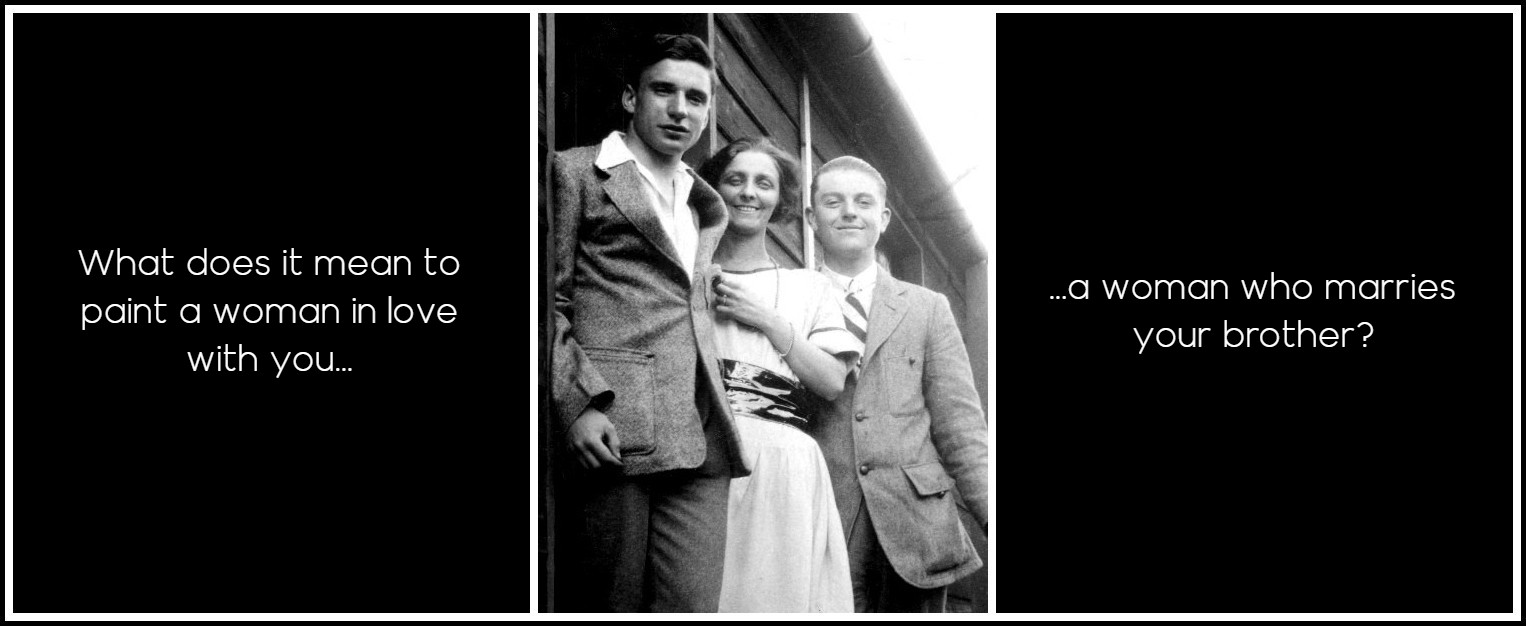

In a sense, then, some of the best contextual material we have in which to situate Manet’s paintings of Morisot has to do with Morisot’s real feelings for Manet. It follows that the historian might attempt to produce an analytical method not out of what might be read of the artist’s intentions, but rather, out of a reverse-intentionality hypothesis of sorts: the impact of the sitter’s intensity of feeling. Instead of asking: what does it mean to paint certain family members again and again, one might ask, what does it mean to paint a woman in love with you, a woman who marries your brother?

Photo: Brett Jordan, Unsplash

The Balcony was exhibited at the Salon of 1869 bearing the title Le Balcon. The title recalls a poem from Les Fleurs du mal, although the tone of the painting is no longer as Baudelairean as that of the paintings from the early part of the decade. The theme not only recalls Goya’s foursome, but also one of Manet’s memories from his trip to Rio: For the somewhat artistically minded European, Rio de Janeiro offers a cachet all its own; in the street one meets only blacks; the Brazilian men go out little and the Brazilian women even less; one only sees them going to mass or in the evening after dinner; the women are seated at their windows; it is then permitted to look at them more at your ease, for in the daytime if by chance they are at their windows and catch you looking at them they withdraw quickly. Manet was seventeen when he described the discretion of white Brazilian women, who did not support a culture of others’ pleasure in gazing (or perhaps did, but in a more rarified way than Manet imagined the women of his own culture). Regardless of whether The Balcony was actually painted entirely in Boulogne or meant to comment on Haussmannian balconies in Paris, the models present themselves without the secrecy, veiling, and modesty suggested by Goya in his Spanish painting, or by Manet in his account of Brazil.

Goya, Majas on a Balcony, 1805 | Berthe Morisot, On the Balcony, 1871-72 | Manet, The Balcony, 1869

As she leans forward and looks intently out the window, Berthe Morisot holds the consummate object for concealing the face—the fan—but she keeps it folded here. Whereas Goya’s female figures lean toward each other and their veils as well as the masks of the male figures behind them create an air of quiet communication and discretion, Manet’s figures do not appear interested in sharing secrets. No flirtatious games are being played at the moment; Morisot’s fan is at the ready, casually clasped by fingers improbably lengthened to curl around each other and the wrought-iron railing of the balcony. Manet paints the full intensity of the face, a visage that virtually beams its gaze out of the picture.

Manet, The Balcony, 1869 (detail)

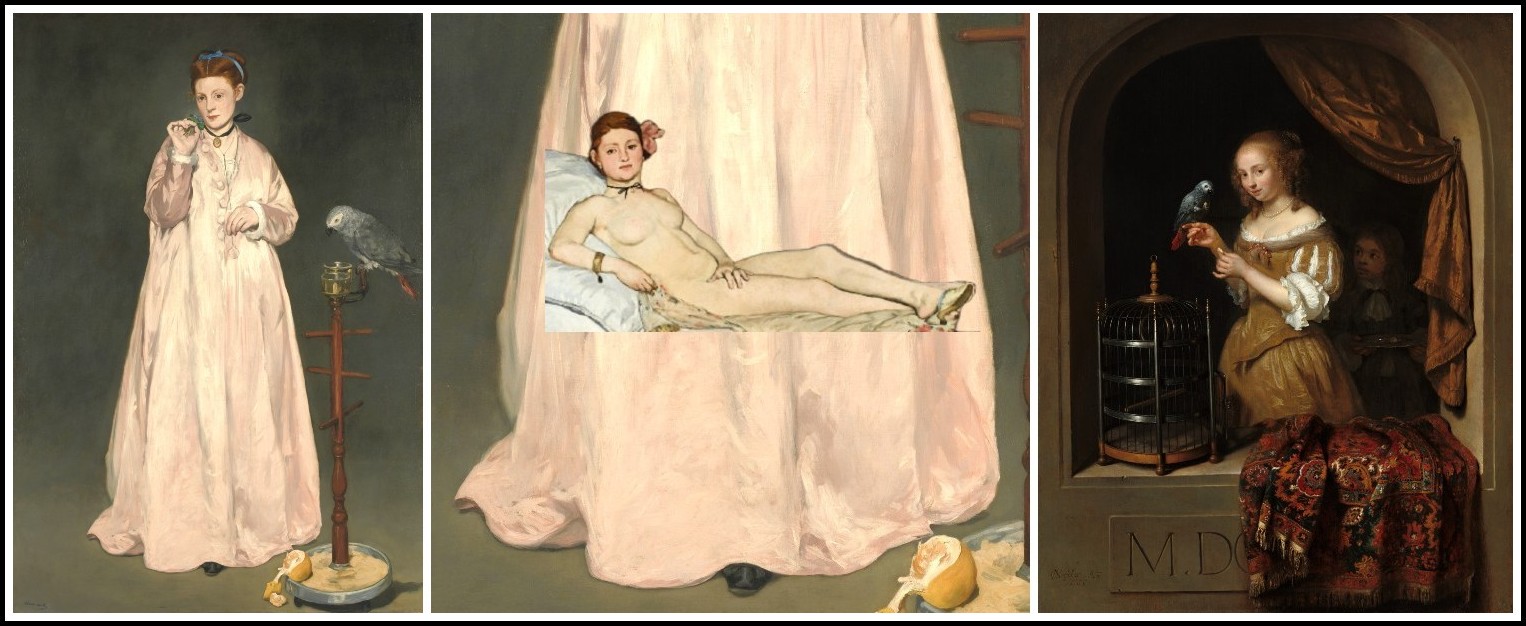

Given Manet’s own musings on balconies as places where women in particular could station themselves or retreat from public view, I think it is not overstating matters to stress Morisot’s bold presence here. The artist-model does not impart anything of the self-consciousness of being the object of the spectator’s gaze that is characteristic of so many Manet images of women, certainly those of Victorine Meurent. Take, for instance, the example of Meurent in Woman with a Parrot. In that painting, the model toys with an object directly associated with the activity of looking: a monocle. In her other hand, Victorine holds a bouquet of violets, flowers that would later figure in several images of Berthe Morisot. With Victorine outfitted in a dressing gown, the picture suggests a context of intimacy. All these points make it an ideal comparison with the images of Morisot.

Manet, Woman with a Parrot (Young Lady in 1866), 1866

Woman with a Parrot was painted in 1866 but exhibited at Manet’s one-person show in 1867 and at the Salon of 1868. Like the Woman with Guitar, it signals an interest in seventeenth-century Dutch genre pictures.

Vermeer, The Guitar Player, 1672 | Manet, The Guitar Player, 1866

Like so many of Manet’s large single-figure paintings and unlike most genre pictures, however, the accessories seem to be mere props for a genre scene somehow stripped of its contextual or narrative purpose. Neither parrot, nor monocle, nor dressing gown, nor violets can make the picture cohere as a genre painting. Manet does imply the presence, or recent visit, of a fashionable man, via the tiny bouquet of violets (seemingly a gift) and the monocle—a man’s accessory, as women of the time wore lorgnettes. These items, however, command far less visual interest than the pink peignoir. As Carol Armstrong has observed, the peignoir is the visual and conceptual pièce de résistance of the painting; it serves to cover up a body last seen naked at the Salon of 1865 even while it paradoxically shows Meurent en deshabillé; it plays flesh tone against a painterly display of fabric that nevertheless remains a flourish of pure paint.

Manet, Woman with a Parrot, 1866 | Manet, Olympia, 1863 (detail) | Caspar Netscher, A Woman Feeding a Parrot, with a Page, 1666

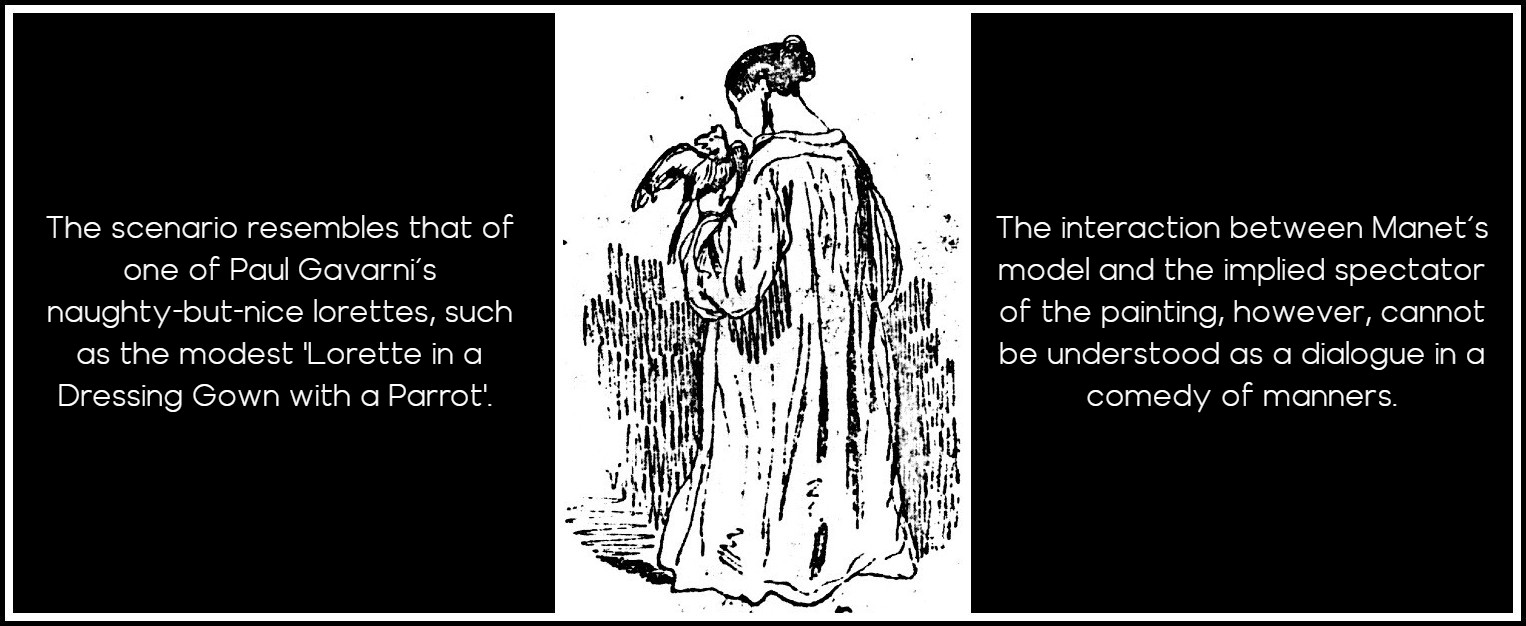

The scenario resembles that of one of Paul Gavarni’s naughty-but-nice lorettes, such as the modest Lorette in a Dressing Gown with a Parrot from the Physiologie de la femme, or one of Labiche’s comic plays, in which a prim young woman earnestly tries not to appear to be flattered by a suitor’s gift of violets (she does not allow herself to get too close to them), and is embarrassed by the vulgar utterances of her parrot. These contemporary vignettes, however, will not do as contextual frames of reference; the interaction between Manet’s model and the implied spectator of the painting finally cannot be understood as a dialogue in a comedy of manners. The model toys with the monocle: her left hand, drawn as if to appear almost pawlike in its crudity, clasps the fine chain or string on which it hangs as a pendant. If the monocle indeed belongs to a man, say a man standing in the spectator’s space, then perhaps she toys with him as much as the monocle, since presumably he cannot take leave of her without reclaiming it.

Paul Gavarni, Lorette in a Dressing Gown with a Parrot, 1841

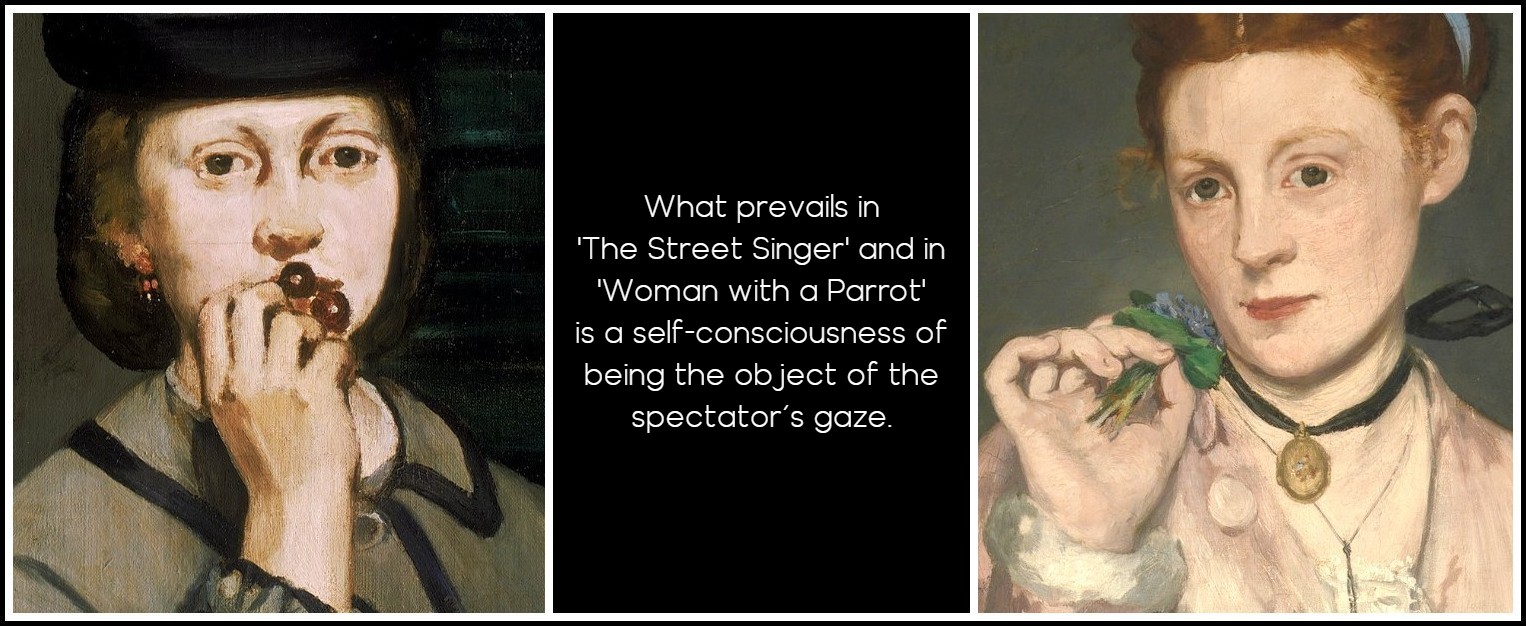

The Woman with a Parrot is not the first image of Victorine Meurent that suggests an exchange of some sort with an implied spectator; The Street Singer, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, and Olympia all deployed it powerfully. Yet the scenic elements in Woman with a Parrot have been pared down: there is no decor to speak of, and only the bird and a few items accompany her. It follows that Manet was tightening his focus on the figure, and on the viewer’s relationship with the figure. With Victorine holding a monocle and bouquet, and appearing in a peignoir, that relationship is certainly intimate, and perhaps even flirtatious. Meurent holds the tiny bouquet of violets as high as her face. Violets can connote many things, but here, considering her dressing gown, a good possibility is an après-theater scene. Perhaps the violets were bought just outside the opera, and now another kind of performance is unfolding between a woman in a dressing gown and the viewer, as the woman holds the (man’s) monocle and the flowers given hours earlier. The situation itself is sensuously rich and extremely suggestive. Is she about to brush the violets against her cheek? Or about to sniff their fragrance? The marvelous openness of her hand invites the spectator to look closely at violets, cheek, and hand. Like Cinderella’s coach at the stroke of midnight, however, the violets turn out to be mere pigment, brushed in next to strokes of flesh-toned cheek in such a way that the viewer cannot confirm their placement in space. The Cinderella story aptly emblematizes Carol Armstrong’s rich formal analysis of the painting’s self-reflexivity: that which most solicits the enjoyments of the senses of sight and smell and touch just as powerfully turns back into paint.

MANET

Olympia, 1863 (detail) | Woman with a Parrot, 1866 (detail) | Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863 (detail)

Yet the painting unravels not only as an illusion but also as a situation. Ultimately it is Meurent’s facial expression that ought to confirm coyness or flirtation, and here is where the painting refuses to play the game of genre or narrative. Just as The Street Singer’s gesture of holding cherries to her lips suggests—but falls short of confirming—the furtive signals of the fleeting encounter, so too the expression of Woman with a Parrot fails to secure the easily readable countenance that is the keystone of nineteenth-century genre pictures. What prevails in Woman with a Parrot, then, as with the other pictures of Victorine Meurent, is a self-consciousness of being the object of the spectator’s gaze. The context of intimate dress/undress here becomes just another role for which Victorine Meurent poses or auditions. It would be a mistake, however, to associate being the object of the gaze with passivity. The Lacanian notion of the object of desire as a kind of mirage holds that, more aura than substance, the object of desire eludes possession. It would likewise be a mistake to compare the activity of looking or gazing upon the object of desire to a vector emanating from the empowered to the powerless. For Lacan, the gaze transfixes or suspends the one doing the gazing. Lacan’s rejection of the active/passive dyad around the gaze would not be foreign to Baudelaire, for whom the flâneur was often paralyzed by his own overwhelming sensation. Even the nineteenth-century man could consider the spectator to be mastered, overpowered by the gaze itself. To say that in Manet’s art, Victorine Meurent was the supreme object of the spectator’s gaze, then, is not to say that she was a passive object. By contrast, it is to say that for Manet, she so completely embodies the role of being the object of the gaze that his representations of her hold or suspend the spectator in the very act of looking.

Manet, The Street Singer, 1862 (detail) | Manet, Woman with a Parrot, 1866 (detail)

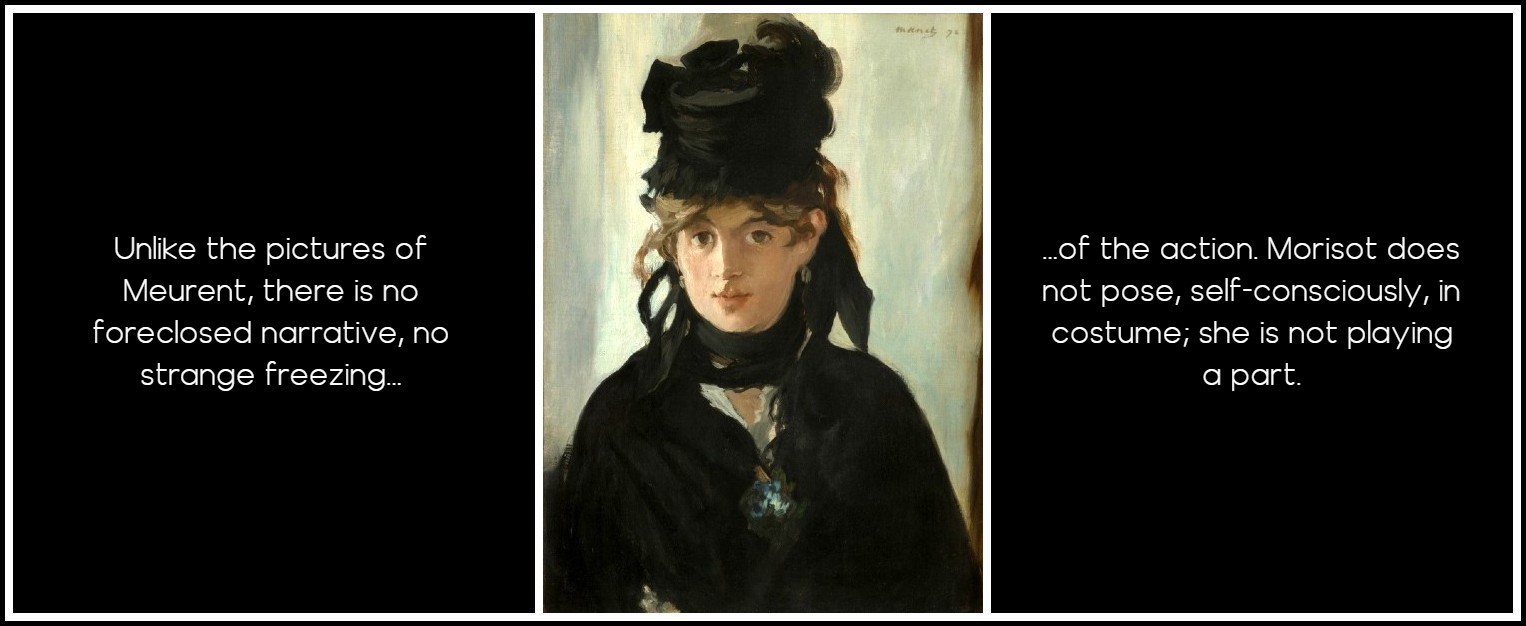

Manet’s paintings of Berthe Morisot are another story. Let us take, for example, the picture her nephew Paul Valery most admired, Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets. When we look upon this portrait, we are far removed indeed from the costumes and props of the Meurent pictures. This is a parisienne; this is one of the gens du monde. Manet might characteristically deploy one of his subtle bits of painterly sleight-of-hand in the inclusion of the tiny bouquet, hardly perceptible against her black dress, or in the framing of her face with ribbons, hair, hat, and scarf encircling her throat. Yet unlike the pictures of Meurent, there is no foreclosed narrative, no strange freezing of the action. Morisot does not pose, self-consciously, in costume; she is not playing a part. By contrast, she very much is the part of the parisienne who knows how to tie a scarf, how to flatter her face with a beribboned hat.

Manet, Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, 1872

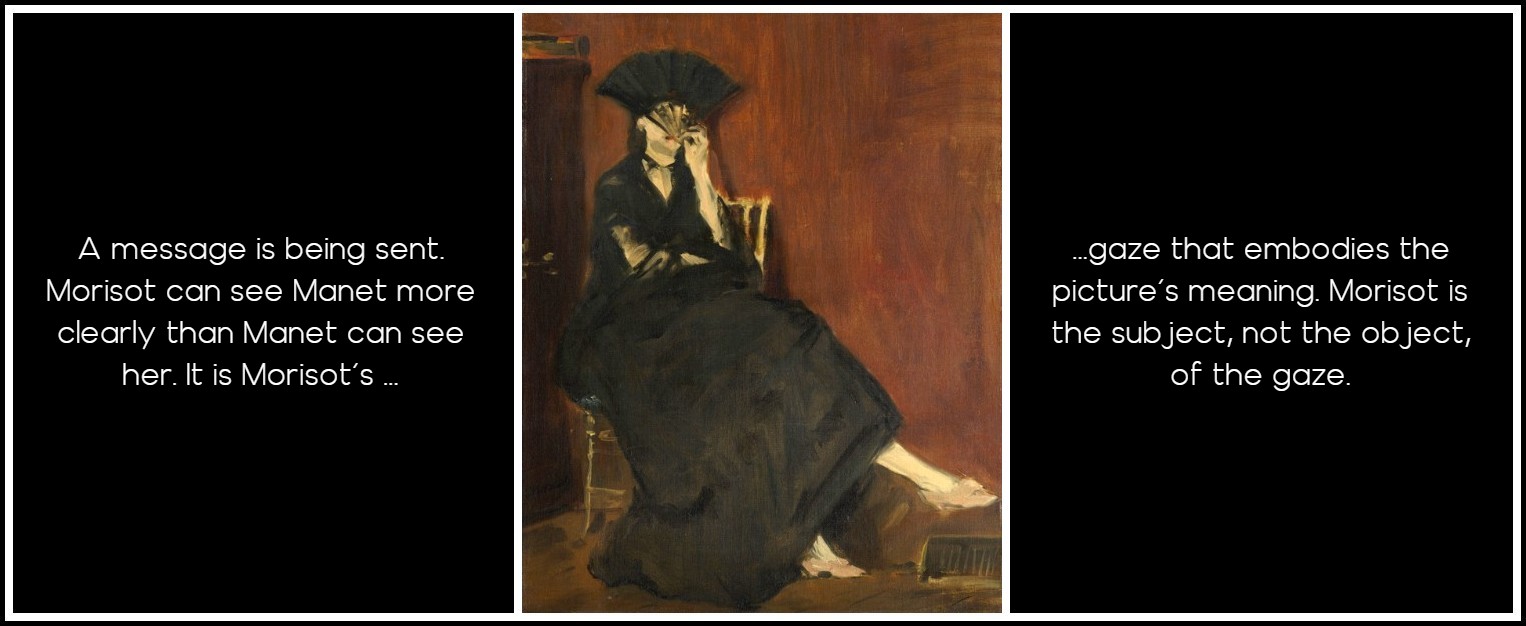

The Morisot pictures are closely involved with details of fashion. In Berthe Morisot with a Fan of 1872, for instance, Morisot also appears in a black dress, with black ribboned choker and sheer sleeves partially revealing her arms. She is seated, legs crossed; she purposely extends one foot in such a way that the hem of her dress audaciously rides up her leg. These bits of revealed ankle and arm, however, merely underline the principle effect of the picture: Berthe Morisot concealing most of her face with a semitransparent fan. She holds the stem of the fan just above her chin; the sides of the fan parallel her revealed jawline; the opaque black portion of the fan projects above her head like some hat out of a Domenico Tiepolo Venetian carnival. Through the fan we can still make out Morisot’s features, but just barely. In her indispensable guide to the proper deployment of fashion accessories, the Baronne Staffe described the fan as an accessory easily adaptable to the needs and situations of individual women. Its communicative versatility enabled the holder to send messages discreetly in the most complicated social situations: one could say ‘I love you’ or ‘I’m mad at you’ to a lover, even with one’s brother watching. It would appear that painter/viewer Manet and model Morisot are alone here. A message is being sent, certainly. Given the fact that we can glimpse an eye through the fan, however, it appears that Morisot can see Manet more clearly than Manet can see her. It is Morisot’s gaze that embodies the picture’s meaning; Morisot is the subject, not the object, of the gaze.

Manet, Berthe Morisot with a Fan, 1872

CONTINUED IN PART 2 (SEE ‘RELATED POSTS’ BELOW)

NANCY LOCKE: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments