The Promises of a Face

EDOUARD MANET & BERTHE MORISOT: THE FAMILY ROMANCE – PART 2

Nancy Locke

Nancy Locke is Professor of Art History & Director of Graduate Studies in Art History, Penn State University.

From Nancy Locke, Manet and the Family Romance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996) pp. 160-171

THIS IS PART 2 OF THE ESSAY. READ PART 1 FIRST.

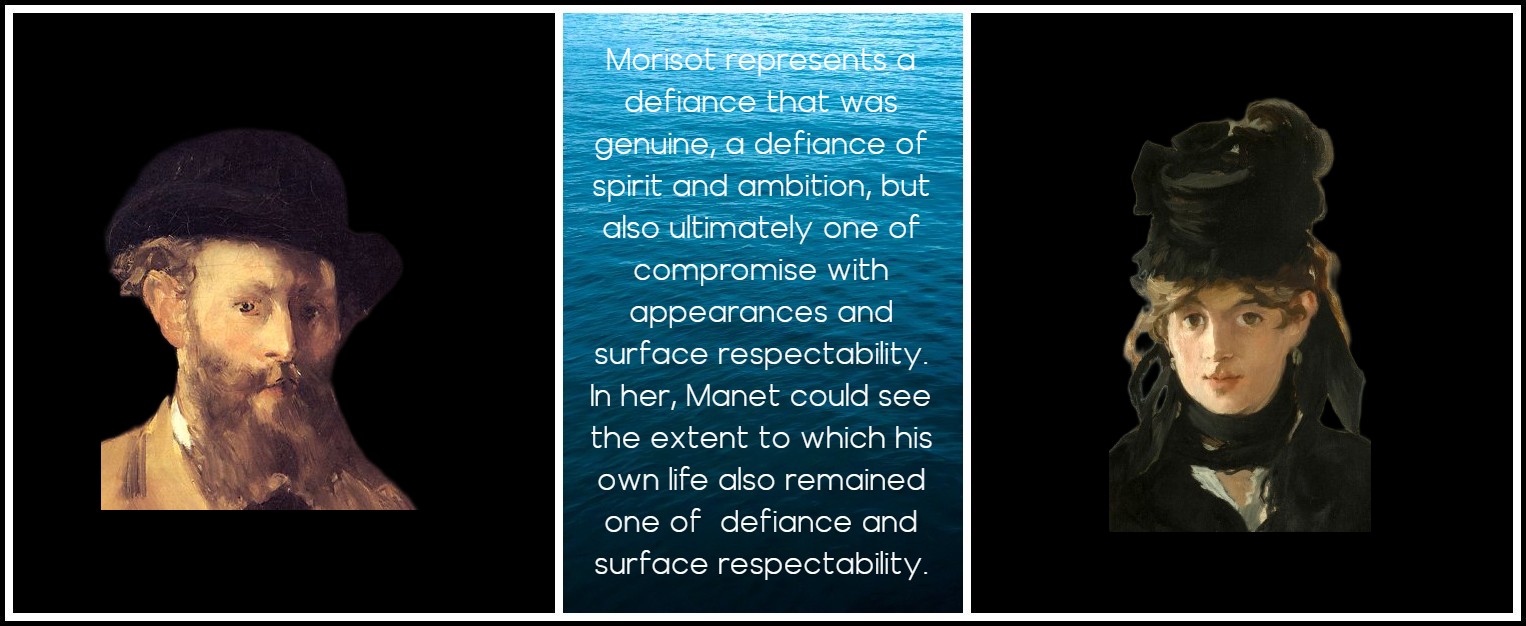

Édouard Manet, Self-Portrait, 1879 | Berthe Morisot, Self-Portrait, 1885

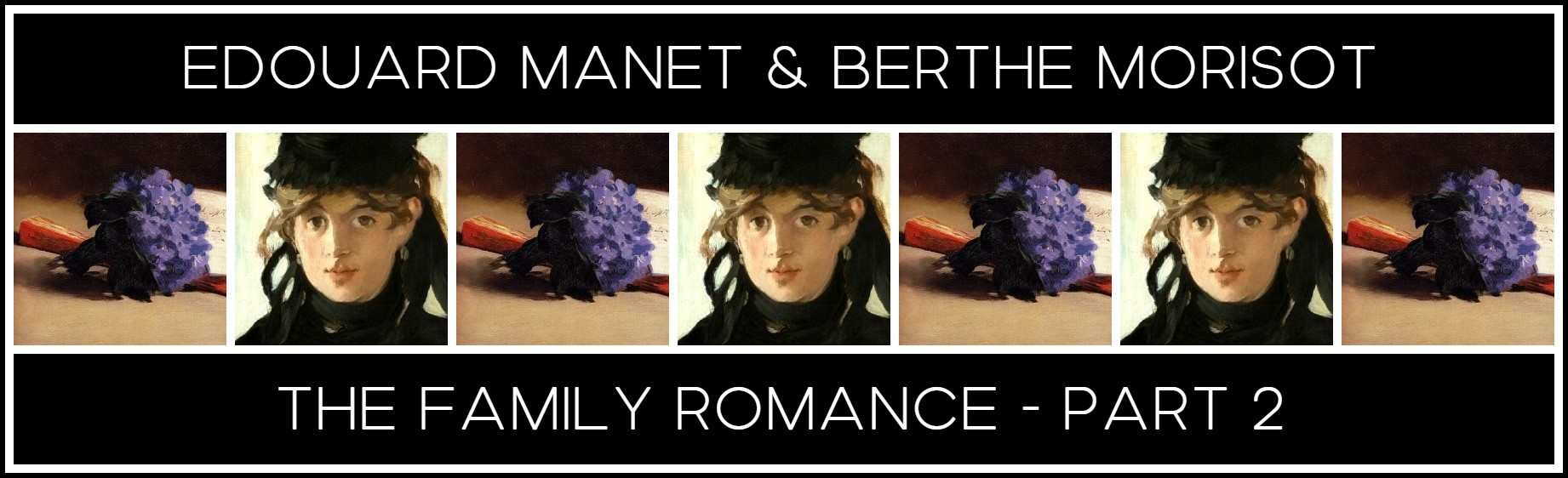

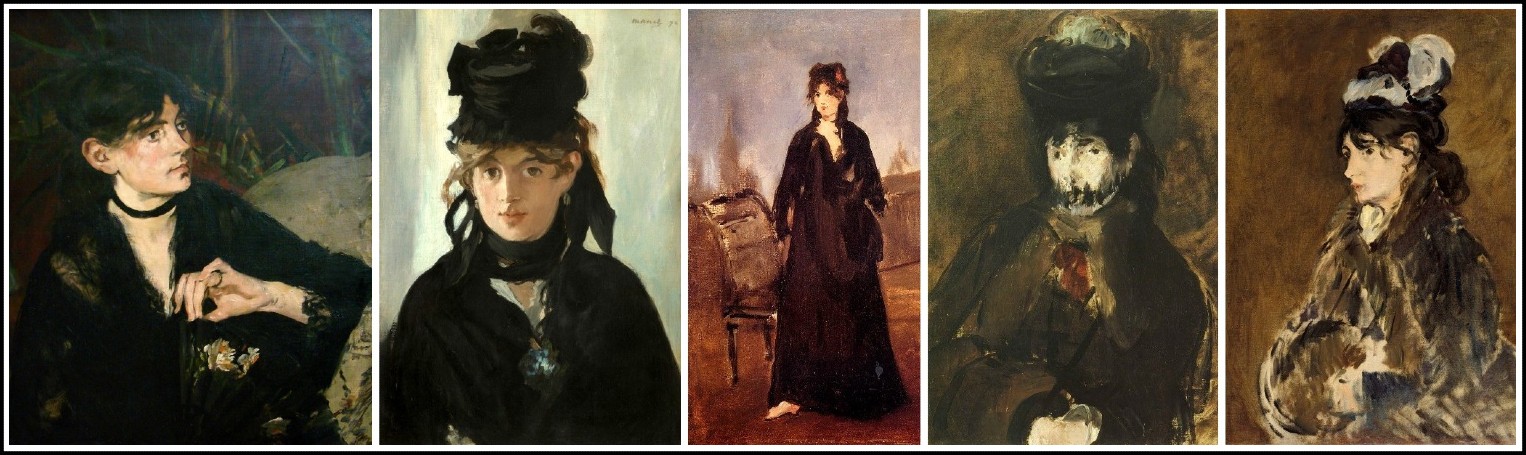

My reading of the Morisot pictures goes against several prevailing views in its emphasis on Morisot as subject. Beatrice Farwell judiciously describes the way the paintings (Le Repos in particular) ‘render formal and decorous portraiture into something informal and intimate’; the paintings conjure images of the reclining woman-as-libertine sort, but precariously balance that reference with a measure of propriety. Anne Higonnet sees a ‘dialogue’ of ‘two intelligences’ in these works and explores the notion that Morisot’s responses to Manet’s art make their way into his paintings of her. In contrast to Higonnet’s emphasis that Morisot’s intelligence influences Manet’s representations of her, Marni Reva Kessler finds that it is Manet as master manipulator who is behind what she sees as the masking, veiling, and ultimately the effacement of Morisot. She reasons that the ‘crucial significance of Manet’s depictions of Morisot lies in this continual shifting of her identity—she looks different from canvas to canvas.’ Where Higonnet sees dialogue, Kessler sees competition: rivalry with Morisot as painter, and rivalry with Eugène for her affection, both of which contribute to the gradual painterly transformation and ‘obliteration’ of Morisot’s identity.

Manet, Le Repos, 1871

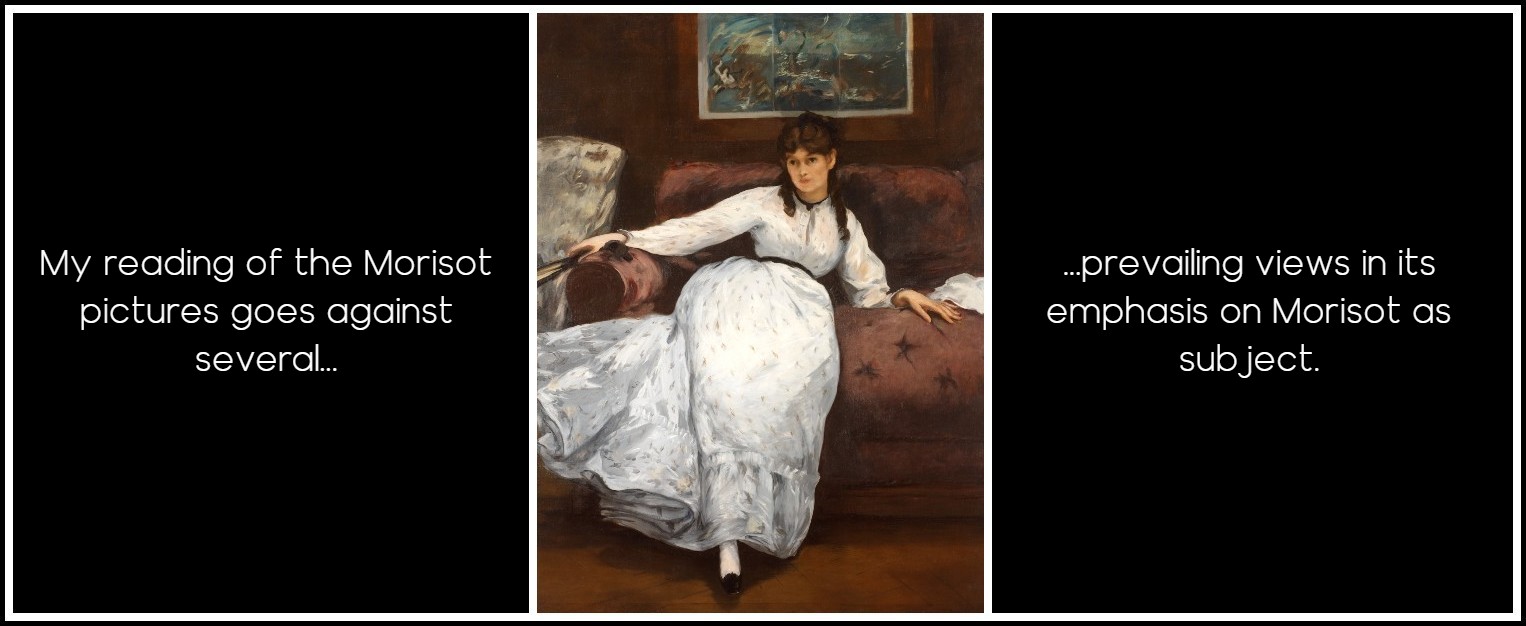

All three authors draw connections between the Morisot-Manet relationship and the pictures’ meaning, whether drawing on biography to illuminate the paintings or relying on the pictures to understand the relationship. In this sense, Kessler’s analysis becomes the most problematic of the three, as she suggests that Manet apparently ‘had to continue to assert his control over Morisot, even if not consciously, while his brother gradually won her affections’. Morisot’s daughter, no less, recalled that it had been ‘oncle Édouard’ who spoke at length to Morisot about the advantages of the marriage to Eugène. Although Morisot was an accomplished artist and no longer a student by the time her friendship with Manet intensified, there is little evidence from paintings and correspondence to support the idea that Manet would have felt very threatened by Morisot as a painter. My thesis does agree with one biographer’s, however. Anne Higonnet’s biography of Morisot also proposes that Manet’s paintings of Morisot ‘are about how she looks, not just in the sense of her appearance but also in the sense of how she gazes at him.’ Higonnet wants to underline the importance of Morisot as painter herself—Morisot as one who possesses a powerful gaze of her own. I have already alluded to Morisot’s gaze as a key point of difference between Manet’s myriad transformations of the model Victorine Meurent when compared with the distinctive emergence of Morisot as subject in the series of paintings of her.

Manet, Berthe Morisot Reclining, 1873 (detail) | Manet, Le Repos, 1871 (detail)

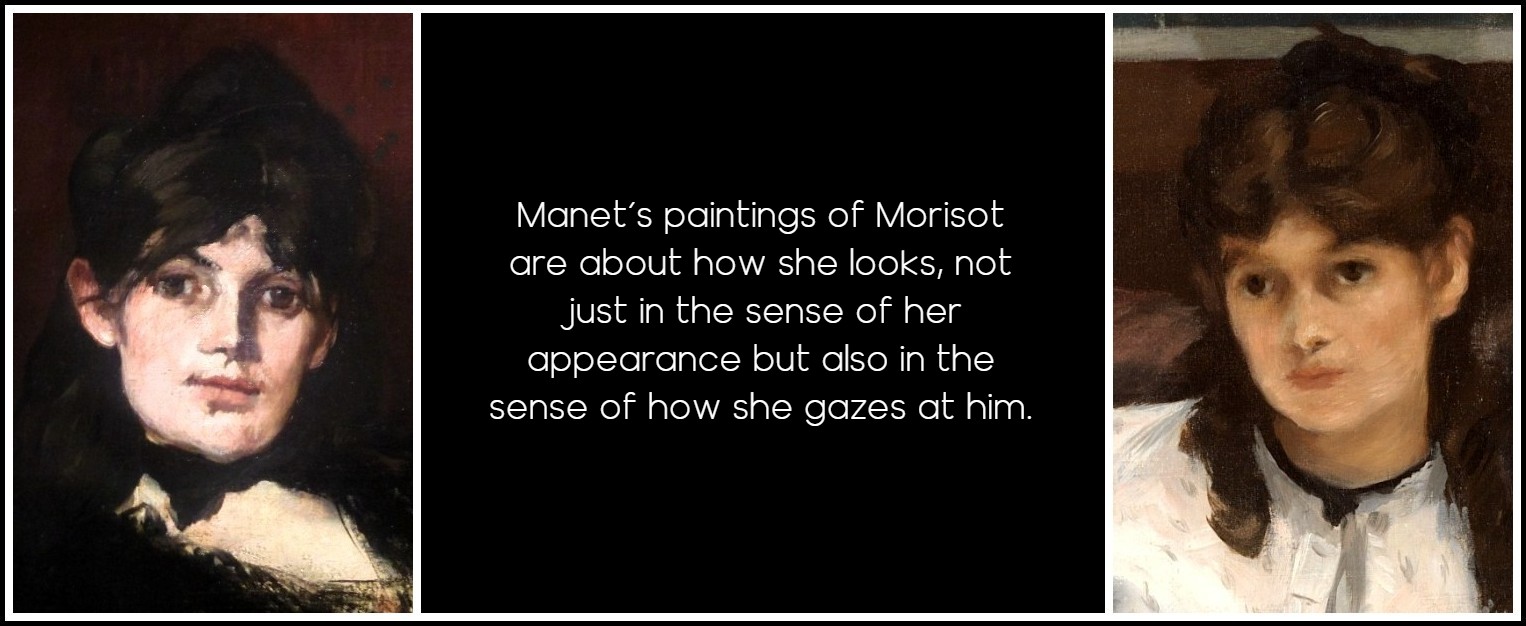

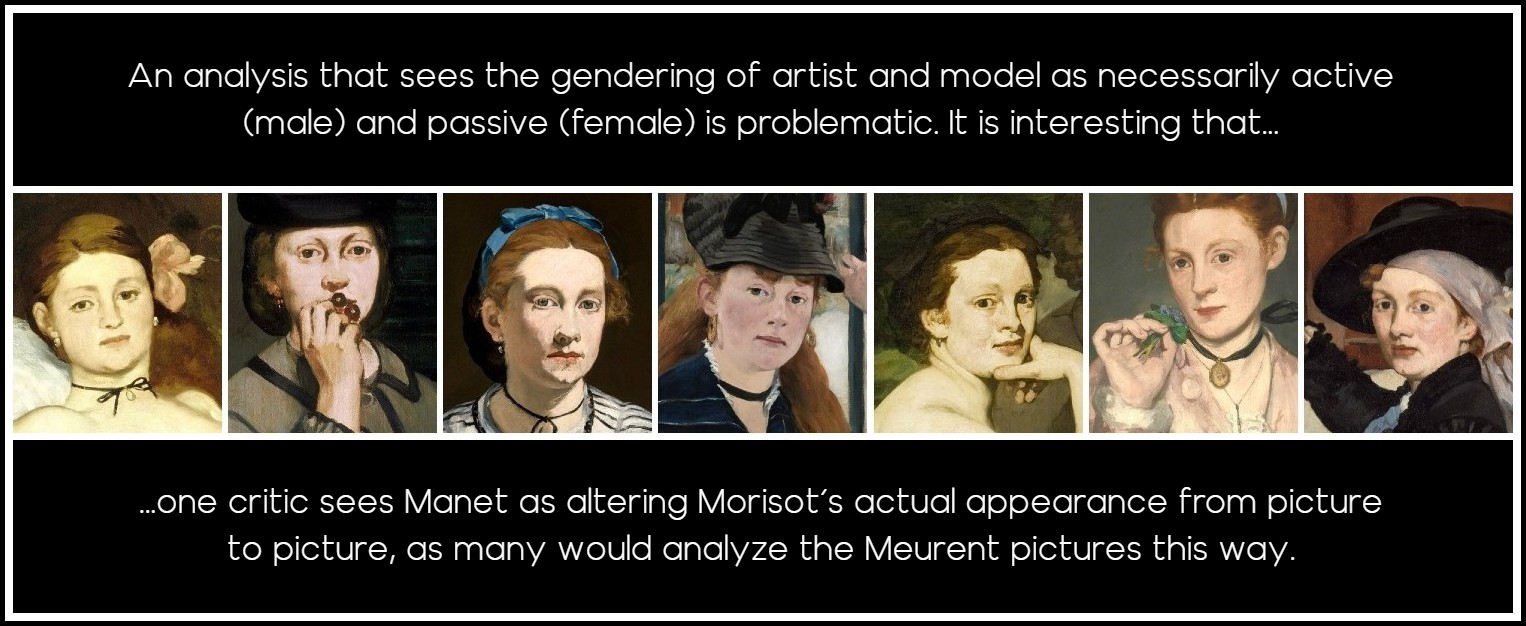

An account of Manet’s series paintings of women necessarily encounters the terms of ‘to-be-looked-at-ness,’ a discourse inaugurated by Laura Mulvey’s essay, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.’ Although this landmark essay was concerned with spectatorial identification and voyeurism on a cinematic scale, for feminist analysis in its wake, it became something of an assumption—not to say a cliché—to rail against the ‘male gaze,’ and hence to consider feminine ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’ as something of an undesirable phenomenon that feminism would eventually transcend. Kessler’s analysis, for example, which has considerable strengths where it concerns the cultural material of fashion, becomes somewhat problematic in its gendering of artist and model as necessarily active (male) and passive (female). It is interesting that Kessler sees Manet as altering Morisot’s actual appearance from picture to picture, as many would analyze the Meurent pictures this way. Perhaps the first account of Manet’s discovery and representation of such endless malleability in a model comes in Baudelaire’s 1864 prose poem ‘La Corde’: the model there, however, was not a woman but a young boy.

ÉDOUARD MANET – VICTORINE MEURENT

Olympia | The Street Singer | Portrait | The Railway (Gare Saint-Lazare) | Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe | Woman with a Parrot | Mademoiselle V. In the Costume of an Espada

In much art-historical writing since the mid-1970s, the oft-encountered equation between the active gaze and the scopophilic drive has remade the viewer into a voyeur where images of women are concerned. Lacan’s analysis of voyeurism is useful in questioning the gendering of the gaze of pleasure. ‘What occurs in voyeurism?’ asks Lacan. ‘At the moment of the act of the voyeur, where is the subject, where is the object?’ ‘Is the activity/passivity relation identical with the sexual relation?’ Lacan queries. His complex musings on voyeurism come out of his reading of Freud’s renowned case study of the Wolf Man. Lacan proclaims that the active/passive binary relation is merely a covering metaphor for ‘that which remains unfathomable in sexual difference.’ The masculine/feminine relation, says Lacan, ‘is never attained’ in Freud’s text. For Lacan, metaphors of activity and passivity in the Wolf Man case denote sadomasochism, not gender. To look for masculine and feminine ideals at work in the psyche, he says, look to Joan Riviere’s notion of the masquerade: a performance of ‘femininity’ in the realm of culture that conceals and encodes unconscious anxieties, usually having to do with the father.

Getty Images, Unsplash | Kateryna Hliznitsova, Unsplash

If one were interested in an analysis of Morisot and the masquerade, Manet’s paintings would offer no shortage of material. Berthe Morisot wears, in various pictures, a muff, a feathered hat, a black hat, a speckled veil, pink shoes, and a fan. Compare the strange deliberation of Victorine Meurent’s pose in Woman with a Parrot to the graceful self-assurance with which Berthe Morisot clutches her throat and extends her light shoe out from under her dress in Berthe Morisot with Pink Slippers. She enigmatically rests chin in hand in Berthe Morisot in a Veil. A scarf or choker adorns her neck in all but one of the pictures. If Morisot did not also project such intelligence in these pictures, one might be tempted to describe her as either a slave to fashion or as someone overly concerned with femininity in her appearance—as someone performing or masquerading womanliness as compensation for her masculine activity as a painter.

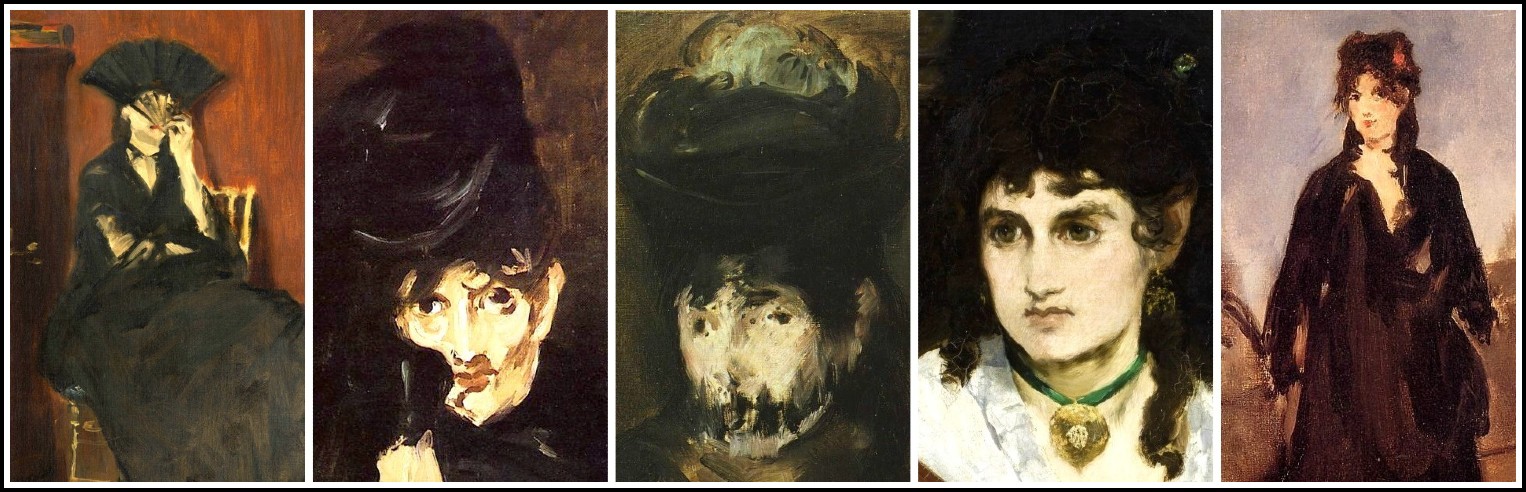

ÉDOUARD MANET – BERTHE MORISOT

With a Fan | With a Bouquet of Violets | With Pink Slippers | With a Veil | With a Muff

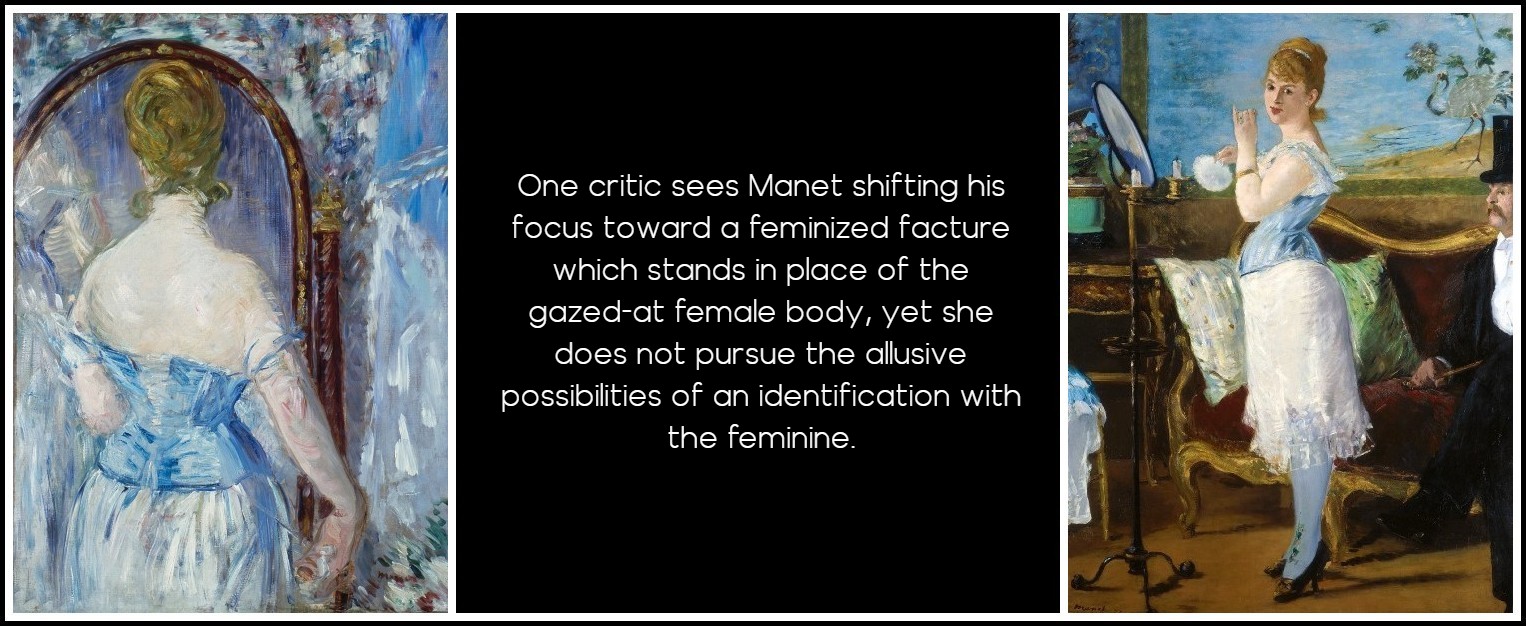

Yet my analysis here is not of Morisot’s possible psychic disposition, but of Manet’s paintings, and here some comments by Carol Armstrong are extremely revealing. Armstrong suggests that Manet’s late work, notably Before the Mirror of 1875-76, is deliberately Morisotian in facture and signals a kind of identification with the feminine. She sees Manet shifting his focus in his late work toward a ‘feminized facture which stands in place of the gazed-at female body.’ Manet’s lighter palette and more feathery, sketch-like style from the mid-1870s on suggests, for Armstrong, an identification ‘of the painter’s process of production with the commodity of femininity: with the feminine process of producing femininity rather than with the ‘male gaze’ onto it.’ This argument adds refinement and precision to one made by Jean Clay, who took up Mallarmé’s suggestion that Manet’s was an art of colored ointments, of makeup, of pigmented powders. Mallarmé’s language in turn evokes Baudelaire’s celebration of the artifice of women’s makeup, surely not lost on the painter of Olympia and Nana. Yet here as elsewhere in Armstrong’s work on Manet, the accent falls not on the identification with the feminine itself but on the notion that Manet’s painting is fundamentally about painting. Thus, despite her sophisticated expansion of Greenbergian modernism, the allusive possibilities of an ‘identification with the feminine’ are left behind in favor of a renewed claim to painting’s self-reflexivity.

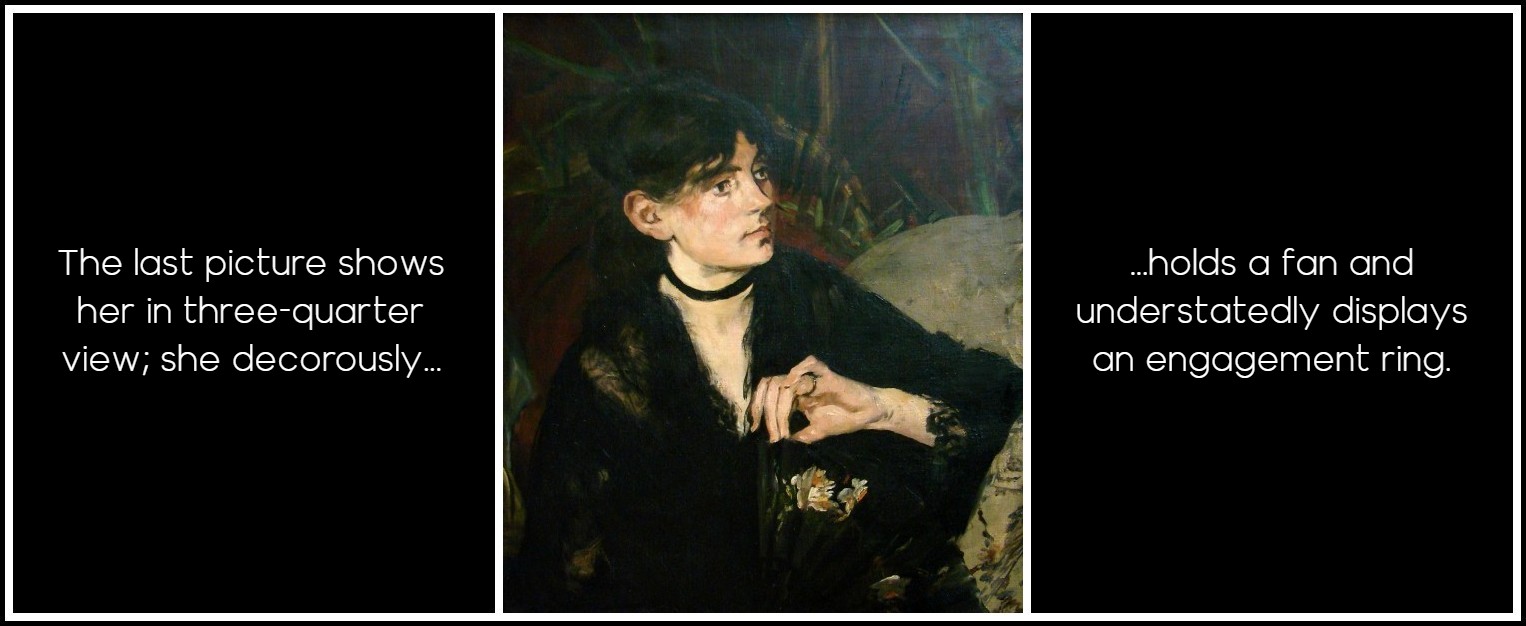

Manet, Before the Mirror, 1876 | Manet, Nana, 1877

Armstrong is surely right to pursue Manet’s exploration, in his late work, of ‘painterly illusionism, femininity, and commodity culture,’ and to substantiate the suggestion of Manet’s painterly debt to Morisot at the level of facture. What she sees as his Morisotian facture, however, comes into being as a response to Morisot’s own artistic innovations, and hence typifies his art after the series of portraits of Morisot had concluded in 1874. It remains to be seen whether an ‘identification with the feminine’ or with Morisot herself might be enacted by the works from 1868 until her last sitting for him (Berthe Morisot with a Fan, 1874). That last picture shows her in three-quarter view; she decorously holds a fan and understatedly displays an engagement ring.

Manet, Portrait of Berthe Morisot with a Fan, 1874

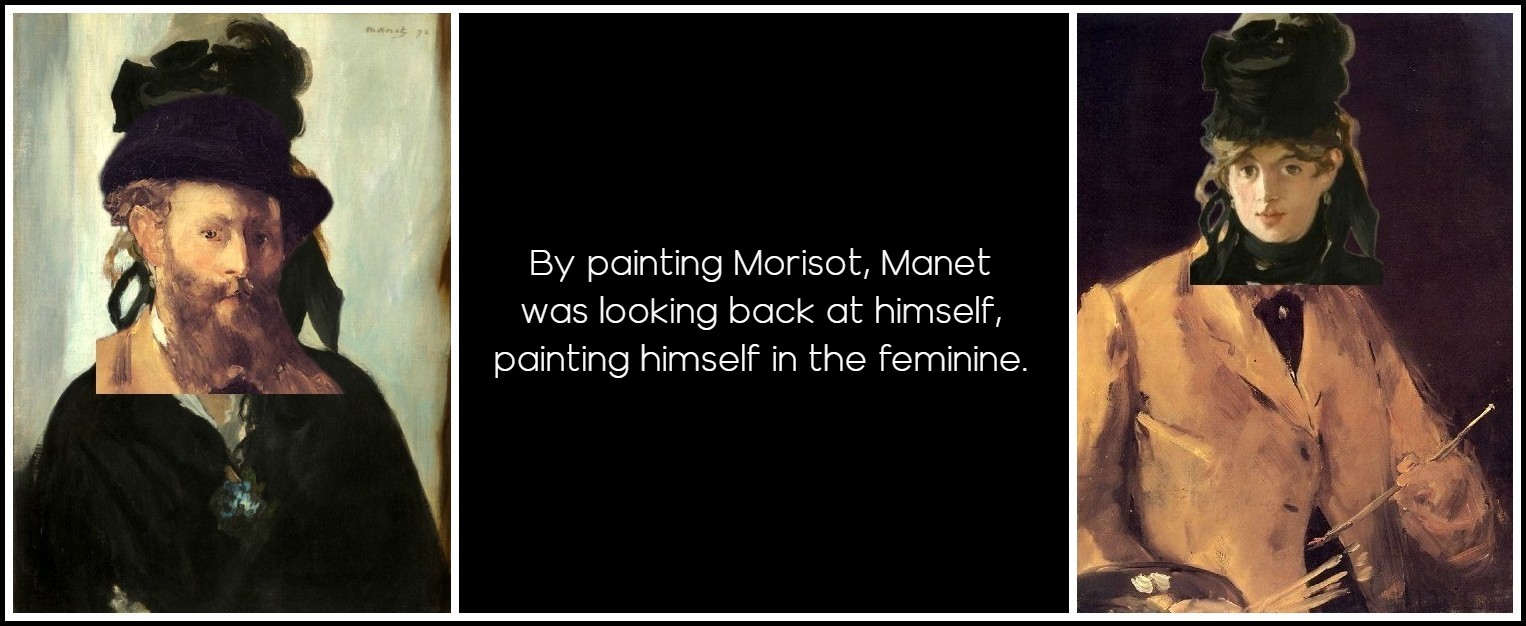

On the surface, Édouard Manet seems like an unlikely candidate for anything like ‘identification with the feminine.’ To him we cannot attribute anything comparable to Mallarmé’s fashion articles and elaborate menus in La Dernière Mode, written under feminine pseudonyms such as ‘Miss Satin’ and ‘Olympe, Negresse.’ But let us return, for a moment, to the scene of painting. Berthe Morisot poses in Manet’s studio. Manet is looking at her looking at him. Let us say—for purposes of the argument here—that Morisot’s look embodies feelings of love for him, love that exists in an ‘impossible’ situation, obstructed by Manet’s status as a married man, his potential interests in other women, the surveillance of Morisot’s mother chaperoning the sittings. (These are not unreasonable readings of Morisot’s preoccupations as gleaned from her correspondence.) Manet begins to try to paint that look. It is a look that positions Manet as the (love) object. In entering into a dialogue of gazes with Morisot, Manet paints a subject gazing at an object (himself ); Manet paints a reflection of sorts: a return of his own gaze that mirrors it, flatters it, enlarges it. By painting Morisot, Manet was looking back at himself, painting himself in the feminine.

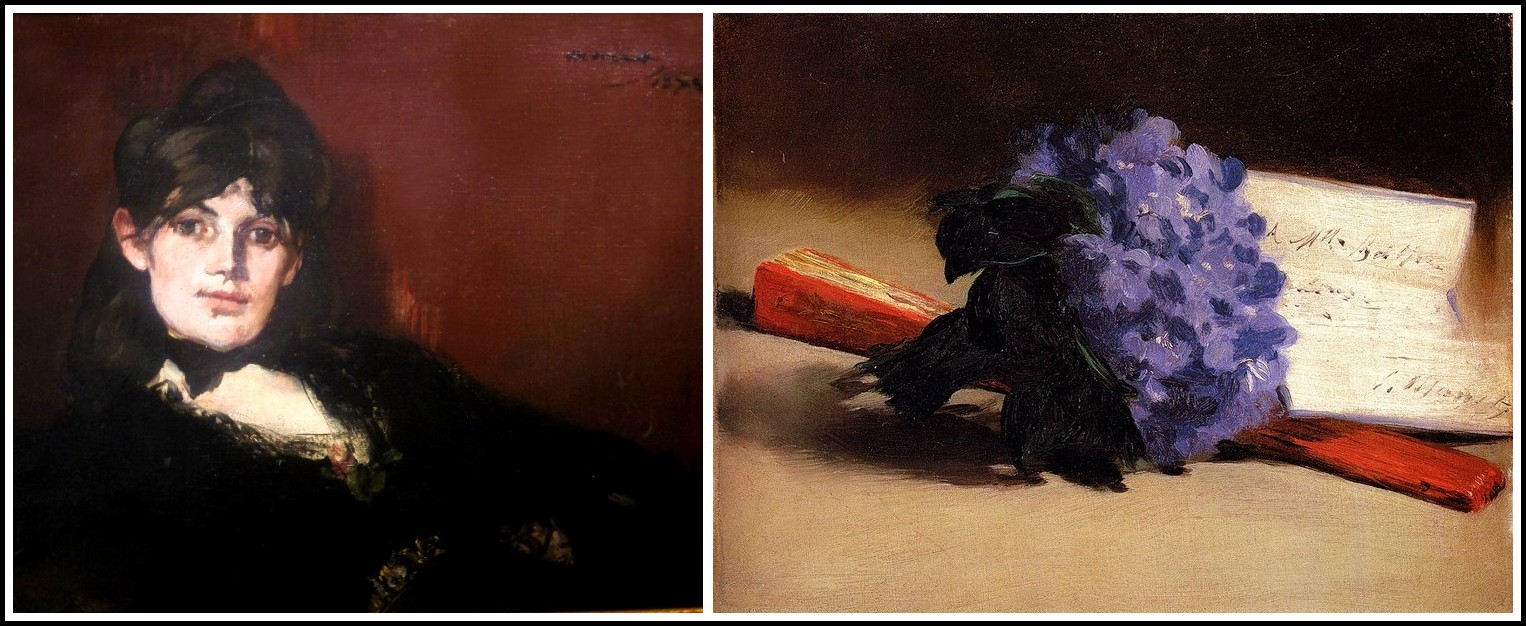

MORISOT AS MANET | MANET AS MORISOT

Manet, Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, 1872 | Manet, Portrait of the Artist (Manet with Palette), 1879

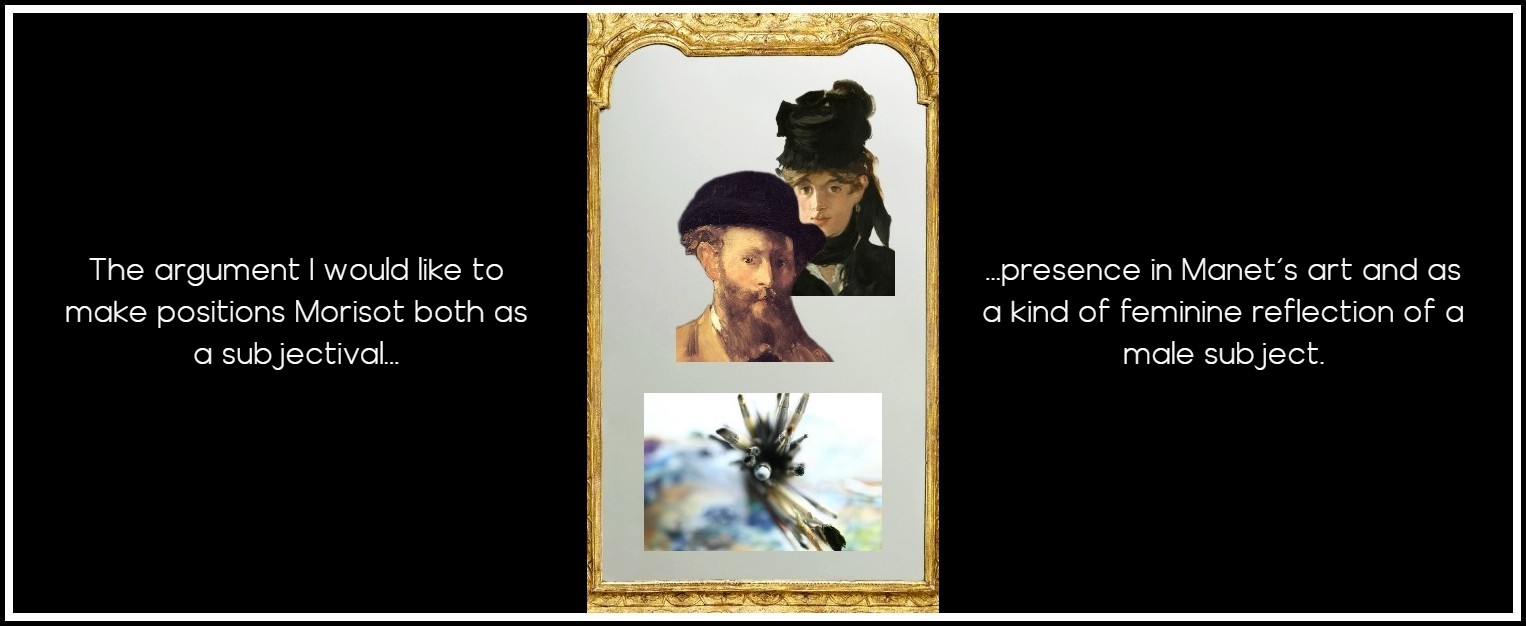

The argument I would like to make here positions Morisot both as a subjectival presence in Manet’s art and as a kind of feminine reflection of a male subject. Morisot’s image, of course, would not represent anything like a literal self-portrait or mirror image, but rather, the projection of an ideal, or what Freud called an ego ideal. Narcissism in Freudian terms involves a damming-up of the libido within the self, in place of what would be a desire ‘to attach the libido to objects.’ Yet narcissism, in a way, is not the same thing as love of the self. It is a love of the self in the other; it is a projection of an ideal onto that image of the self-in-the-Other. As Freud wrote: This ideal ego is now the target of the self-love which was enjoyed in childhood by the actual ego. The subject’s narcissism makes its appearance displaced on to this new ideal ego, which, like the infantile ego, finds itself possessed of every perfection that is of value. As always where the libido is concerned, man has here again shown himself incapable of giving up a satisfaction he had once enjoyed. He is not willing to forgo the narcissistic perfection of his childhood; and when, as he grows up, he is disturbed by the admonitions of others and by the awakening of his own critical judgment, so that he can no longer retain that perfection, he seeks to recover it in the new form of an ego ideal. What he projects before him as his ideal is the substitute for the lost narcissism of his childhood in which he was his own ideal.

Édouard Manet & Berthe Morisot

According to Freud, in narcissism, there is an attempt to recover—in the process of setting up an ideal ego in an Other—an infantile state in which the subject was his own ideal. Narcissism, in Freud’s own text, is less a state of recognition of the self in the Other, and more a state of projection of something the self has not been or cannot be (although it may imagine it has been or could be). The act of seeing the self, or the ideal ego, in the Other or in the image, becomes an act of foreshadowing, wishing, projecting; it is anything but a regressed or static fixation on the self. One could say that in Manet’s paintings of Berthe Morisot, there is a projection of the self onto a portrayal of the Other’s gaze at that self, and that projection becomes legible in the act of viewing. The viewer comes to stand in the place of the self who sees himself/herself in the Other. The sitter’s look out of the picture and at the viewer becomes a transcription of the painter’s look in the mirror, and at that armature of the self which always remains somewhat foreign, somewhat Other. The representation of the model’s gaze is, in fact, the gaze of the self as Other inviting the viewer to assume its otherness.

Édouard Manet & Berthe Morisot | Background photo: Pierre Bamin, Unsplash | Composite: RJ

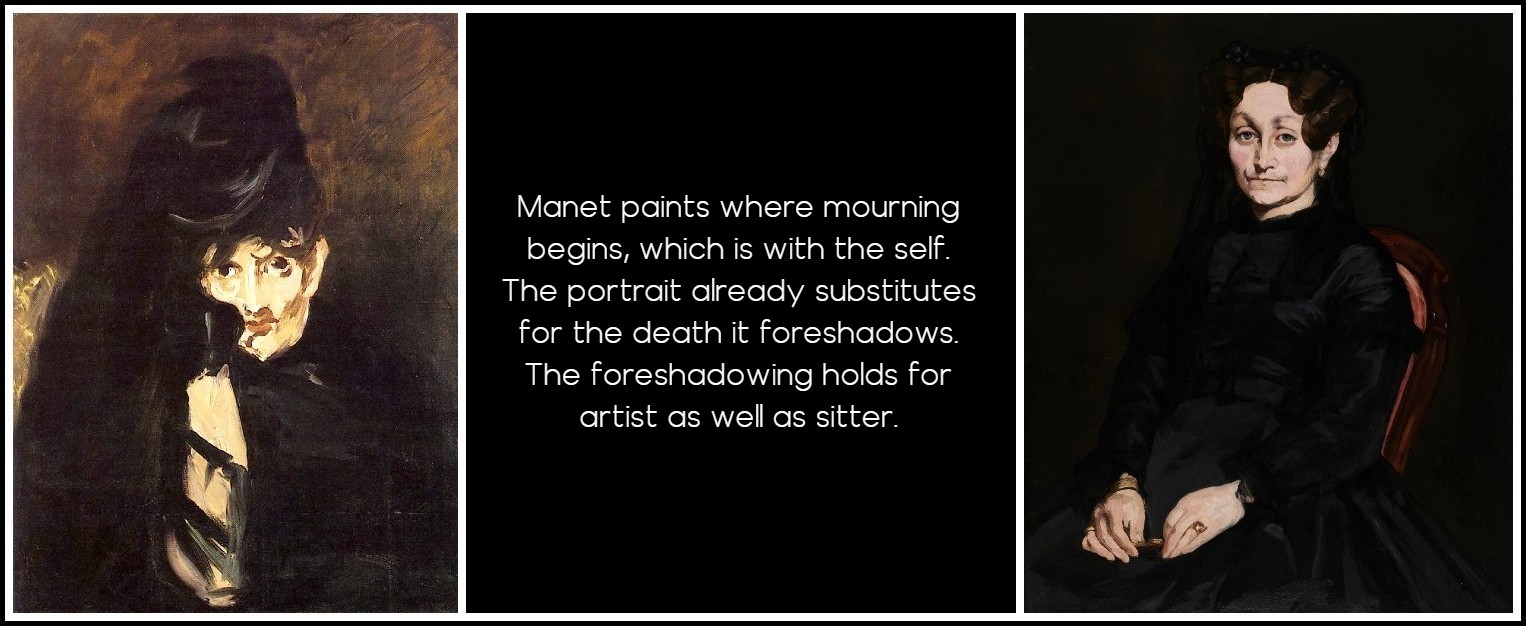

An act in which the self confronts its own otherness is, in this case, not only tied into narcissism, but also to an encounter with death. Jean Clay has a memorable description of Manet’s Portrait of Berthe Morisot with Hat, in Mourning of 1874, a highly unfinished painting that depicts her in mourning after her father’s death: ‘something like a portrait from death—already substituted for the death it foreshadows. An image in the future perfect tense, where mourning begins: I paint while knowing that this portrait will survive you; I paint what you will have been.’ In the act of painting a portrait, Clay seems to be saying, the artist imagines the portrait surviving the sitter; the painting becomes a memorial even as its subject is the sitter’s own mourning of her father. I would extend this idea a bit to include the artist’s self-reflection in a portrait. Because the portrait is not only a likeness of the sitter, but also the artist’s conception of a spectator—not necessarily himself—who looks at the sitter looking at the artist-spectator, the portrait involves both the artist’s self-reflection and his projection of a spectator who will take his place in front of the picture, viewing the sitter looking out. The portrait of Morisot in mourning, then, is not only Manet’s attempt to depict her contemplating her father’s death, but also an evocation of the spectator’s contemplation of death, whether that means the painter-as-spectator or the spectator who will stand in his place.

Manet, Berthe Morisot with Hat, in Mourning, 1874 | Manet, Portrait of the Artist (Manet with Palette), 1879

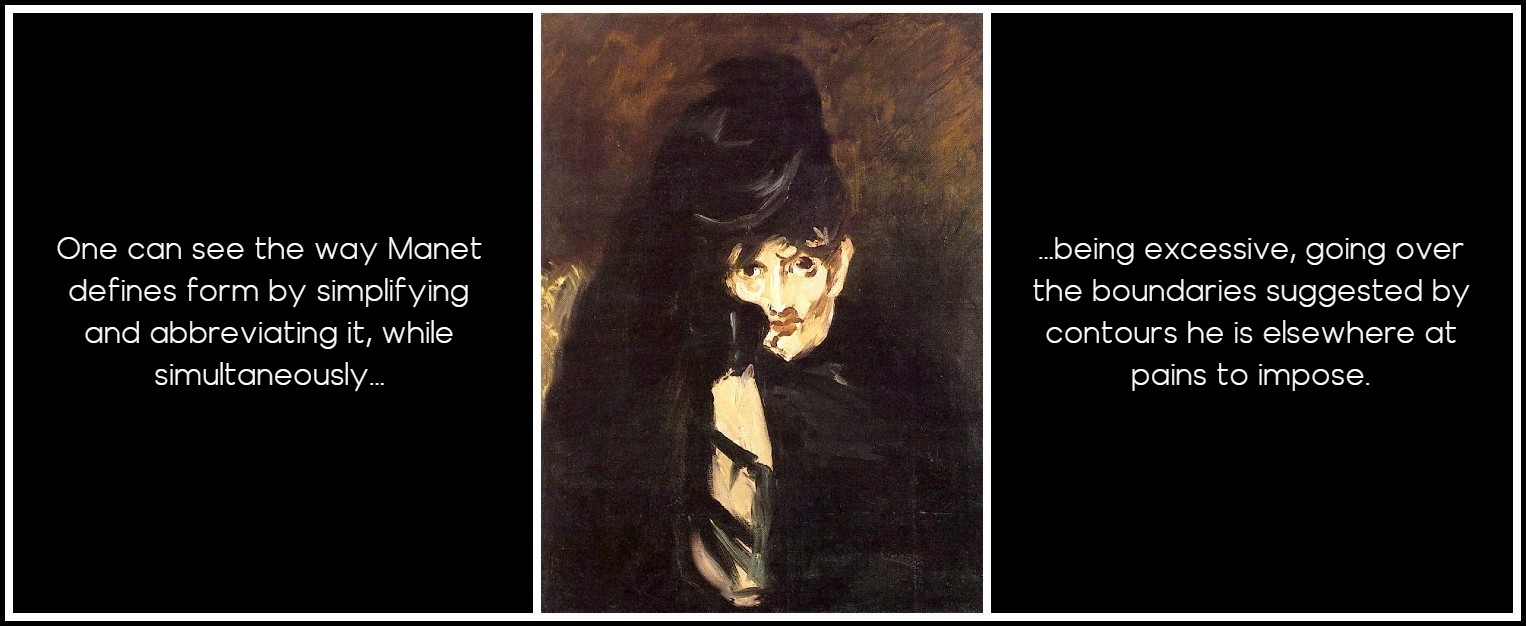

Because of the unfinished state of the portrait, one can see aspects of Manet’s technique that are not always apparent in other canvases. One can see with an astonishing degree of clarity, for instance, the way Manet is always defining form by simplifying and abbreviating it, while he is simultaneously being excessive, going over the boundaries suggested by contours he is elsewhere at pains to impose. In the unfinished portrait, a few strokes of light flesh tones, with a maximum of white, define the nose and the plane of the left cheekbone. Recessed areas below the nostrils and mouth are suggested by unblended strokes of a warm burnt sienna. Manet has begun the process of blending the right cheek: above the cheekbone, there is a blended flesh tone which keeps to the definition probably made originally with more white, as on the left side; there is also, below the cheekbone, the beginnings of blending in which the shadow below the bone itself eventually meets the more illuminated area of the chin. Looking at the left cheek—sharply captured by two almost-white strokes, one C-curve and one S-curve—one could say that these strokes, this kind of drawing, come almost from the realm of caricature. The right side of Morisot’s face is clearly different, in part because Manet has begun the process of blending light and dark. Morisot’s chin is still a diamond shape, as Manet has not yet fashioned it into a more organic form. This angular form suggests a line that would form her jawline; it is more or less a continuation of the line of her chin. Yet below the suggestion of this jawline, which is the jawline of a slender, youthful woman, are strokes of paint that blur its definition. Shadows from below the cheekbone are blended in such a way that they merge with what must be her neck. Manet paints a kind of Cézannian passage in which a few strokes of paint come to stand for jawline, neck, and the shadow below the cheekbone in such a way that the contour of the face has been completely blunted. The exaggerated, hyper-definition of the left side of the face manages to coexist with what seems to be the impossibility of definition at right.

Manet, Berthe Morisot with Hat, in Mourning, 1874

The painting was one that remained in Manet’s studio. We can only speculate about the reasons for its remaining unfinished. Most of the portraits of Morisot—seven, in fact—remained in Manet’s inventory, and two were gifts to Morisot. Even the ones sold went to friends and collectors who were practically handpicked. These facts attest to the personal importance of the paintings for both artist and sitter, and perhaps the extent to which Manet cared deeply about the paintings’ future. Portraits, as Jean Clay implies, are very much about the memorial act: at some level they attempt to evoke the sitter for posterity. Considering the uniqueness in Manet’s oeuvre of such an ambitious and experimental range of portraits as those of Berthe Morisot—all of which are, above all, portraits as opposed to modern-life genre scenes or histories—one can hardly dismiss Clay’s suggestion that the mourning-portrait might have been painted with a view toward its survival of the sitter. Yet the portrait is a record not so much of the way Morisot revealed to Manet an aspect of herself, but a record of Manet’s revealing what he saw Morisot revealing to him as if she were herself revealing it to the spectator. In an act of painting that simultaneously brings Morisot into focus in a highly exaggerated way, even while it suspends the possibility of resolution of its portrayal, the portrait, it seems, wants to highlight not just its sitter, but also some exchange between the artist and his sitter. And in light of what I see as Manet’s imparting of subjectivity, and even selfhood, to the portraits of Morisot, the portrait represents more than the projection of a memorial of Morisot. It is also a memorial of Manet.

Photo: Rémi Jacquaint, Unsplash

To return to Jean Clay’s remarks: Manet paints ‘where mourning begins,’ which is with the self. For Clay, the portrait ‘already substitutes for the death it foreshadows’. I would add that the foreshadowing holds for artist as well as sitter. We might thus quote Clay again with another substitution: ‘I paint while knowing that this portrait will survive us both.’ The portraits of Morisot are, of course, not the first portraits of a woman in mourning in Manet’s art. One might compare Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets to the painting that must be regarded as Manet’s foundational mourning-portrait, that of his mother. The asymmetry between the two halves of the face results in one half projecting a particular engagement with the spectator even as the other half registers a self-conscious awareness of the spectator’s gaze. There is a similar asymmetry in the Morisot portrait, though in my view there is not the same kind of self-consciousness in the Morisot pictures. Both faces, however—Mme Manet’s and Morisot’s—are encircled by black. Unlike the modish entanglement of ribbons and scarves around Morisot’s face, there is a sea of black engulfing the face and hands of Manet’s mother. It appears that at least one of Manet’s preoccupations in the maternal portrait is an exploration of subtle distinctions among the various blacks that make up the painting: the dress, background, veil, ribbon, trim, belt, buckle. The mother’s face and hands become even more imposing as the flesh tones project forward against the black ground. Comparing the two paintings, the flesh of Mme Manet has a weight—the weight of age, perhaps—which that of Mlle Morisot lacks; there is a tremendous contrast between the thin, narrow lips and thick facial hair of the older woman and the beautiful, full lips and light, supple skin of the younger. What remains the dominant tone in both paintings, however, is the way the woman’s face practically floats out of the painting, encircled by black. The uncanny visual effect of decapitation achieved in the Morisot picture is first accomplished in the portrait of Manet’s mother.

Manet, Berthe Morisot with Hat, in Mourning, 1874 | Manet, Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, 1863

In Manet’s other paintings of Morisot, one notices a pattern of accessories and poses that have a similar visual effect of severing or isolating the face. Look at the emphatically thicker layer of pigment tracing Morisot’s hair, hat, and green choker, encircling her face, in The Balcony; look at the unusual placement of her hand covering her throat in Berthe Morisot in a Veil and Berthe Morisot with Pink Slippers. As we have seen, the face is almost completely concealed in Berthe Morisot with a Fan and never quite revealed in the unfinished mourning-portrait. Manet’s interest in the face of Berthe Morisot is clearly something quite distinct from the costume fantasies of Meurent. It surely goes beyond the simple sexual metaphors of Baudelaire’s ‘Les Promesses d’un visage,’ in which details of eyes and head of hair tell of flesh and hair elsewhere on the body, yet to be uncovered. Kessler is right to deconstruct the function of the veil in the visual culture of Manet’s time, as the veiling effects in the Morisot pictures eroticize even as they decorously drape the female model. To plumb the depths of decapitation fantasies, we have to move forward decades in time to Surrealist photography and Documents, to the musings of Michel Leiris on the full-face leather mask as reminiscent of the decapitated queen, her body revealed by the complete covering of her face: the masked woman as the caput mortuum, the death’s head.

ÉDOUARD MANET | BERTHE MORISOT

With a Fan | With a Hat, in Mourning | With a Veil |The Balcony | With Pink Slippers

Although there is undeniably an interest in the culture of mourning and death to be felt in some of the Morisot pictures, it is not a leitmotif for them all. The carefully represented instances of mourning attire or muffs or veiled hats do tell us, however, that even if these works are portraits, they also function as paintings of modern life. To the extent that the painting of modern life in general is bound by the ideologies of family and class, it becomes in a sense a fiction: a representation meant to dream, to imagine transgressions of societal or familial sanctions. Think of the Morisot pictures, with their experimental range and playful intimacy, somehow stacked alongside a portrayal of the decorum of bourgeois marriage. Manet images an intelligent, cultivated, beautiful woman of means who can be seen to represent a freedom not unlike that of Isabelle Archer in the first half of Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady. And even as Morisot is a figure of the upper-class educated woman, she is also, in pictures like Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, an upper-class woman in mourning, a figure reminiscent of Manet’s mother after his father’s death. Somehow Morisot becomes all of these things: available and desirable while proper (not like Meurent), the woman in mourning after the death of the father (Manet’s or Morisot’s), and the woman who can represent Manet himself—charming and an artist (too bad she’s not a man).1

1 – I agree with you, the young Morisot girls charming. It’s a pity they’re not men. Édouard Manet to Henri Fantin-Latour

Édouard Manet & Berthe Morisot | Background photo: Pierre Bamin, Unsplash | Composite: RJ

To dream of transgressions of societal and familial sanctions is almost certainly part of the brief of the Morisot pictures, yet the dream is only nurtured and kept alive by its own impossibility. Evidence of an oscillating response to the potentially compromising appearance of the situation can be found throughout the pictures. The association of Morisot with invitations and violets exchanged by lovers, as in Bouquet of Violets and Fan, connotes a flirtation kept within the boundaries of the proper. Manet’s decision to alter Morisot’s position from a sideways recline to a slight leaning in Le Repos spells out a concern with propriety, as does his cropping of Berthe Morisot Reclining so that it is little more than a bust-length portrait. These are surely not simple matters of pictorial exigencies. They are real instances of the intrusion of the gaze of Others. Manet acts to avoid the appearance of exposing Morisot. In painting her, he becomes the object of the gaze of others—of the Morisot and Manet families, and of society itself. In some sense, the gaze that matters most of all in determining the shape and form of these pictures is neither the gaze of Morisot as subjectival presence nor of Manet as artist, but instead the gaze of others who made the situation ‘impossible.’

Manet, Berthe Morisot Reclining, 1873 | Manet, Bouquet of Violets and Fan, 1872

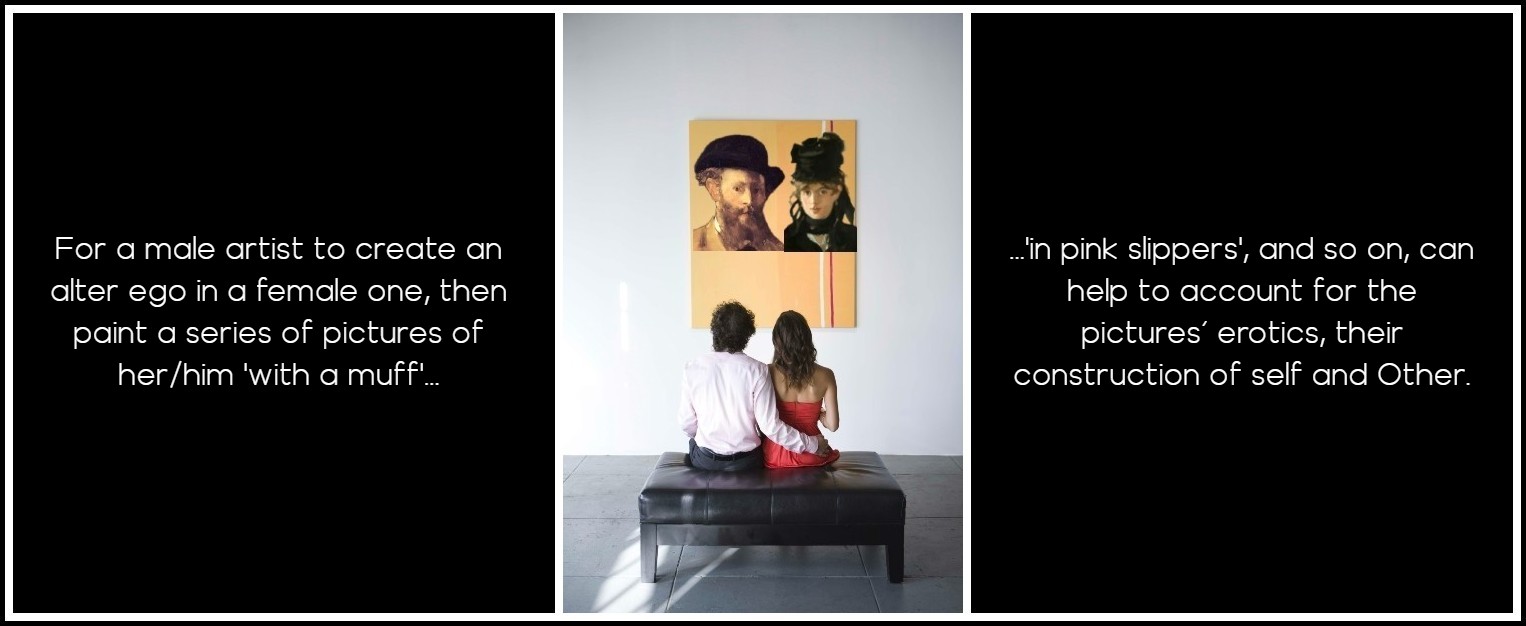

My contention that Manet painted himself as Morisot could be taken as an outrageous one, in need of the most deft practitioner of queer theory to elaborate. After all, it is one thing for Rosa Bonheur to paint in trousers; another for a male artist to create an alter ego in a female one, then paint a series of pictures of her/him ‘with a muff,’ ‘in pink slippers,’ and so on. The stories about Manet’s overdetermined relationship to clothing, although they are traditionally ‘masculine,’ would lend support to his (self-) interest in Morisot’s fashions. This from Morisot herself: ‘Manet spent his time during the siege changing uniforms.’ And Proust reported that Manet, after challenging Duranty to a duel (over the latter’s terse review of Manet’s paintings on exhibition), recounted: ‘I can’t tell you what trouble I went to, the day before the duel, to find a pair of really broad, roomy shoes in which I would feel quite comfortable. In the end, I found a pair in the Passage Jouffroy. After the duel, I was going to give them to Duranty but he refused them because his feet were larger than mine.’ Manet’s behavior can be seen as typical of the nineteenth-century male dandy, although that too is open to analysis as to gender ambiguities. I would not be doing queer theory any justice, however, if I pressed this line very far: I neither mean the claim literally, nor would I like to use it alone to account for the pictures’ erotics, their construction of self and Other.

Photo: Getty Images, Unsplash | Composite: RJ

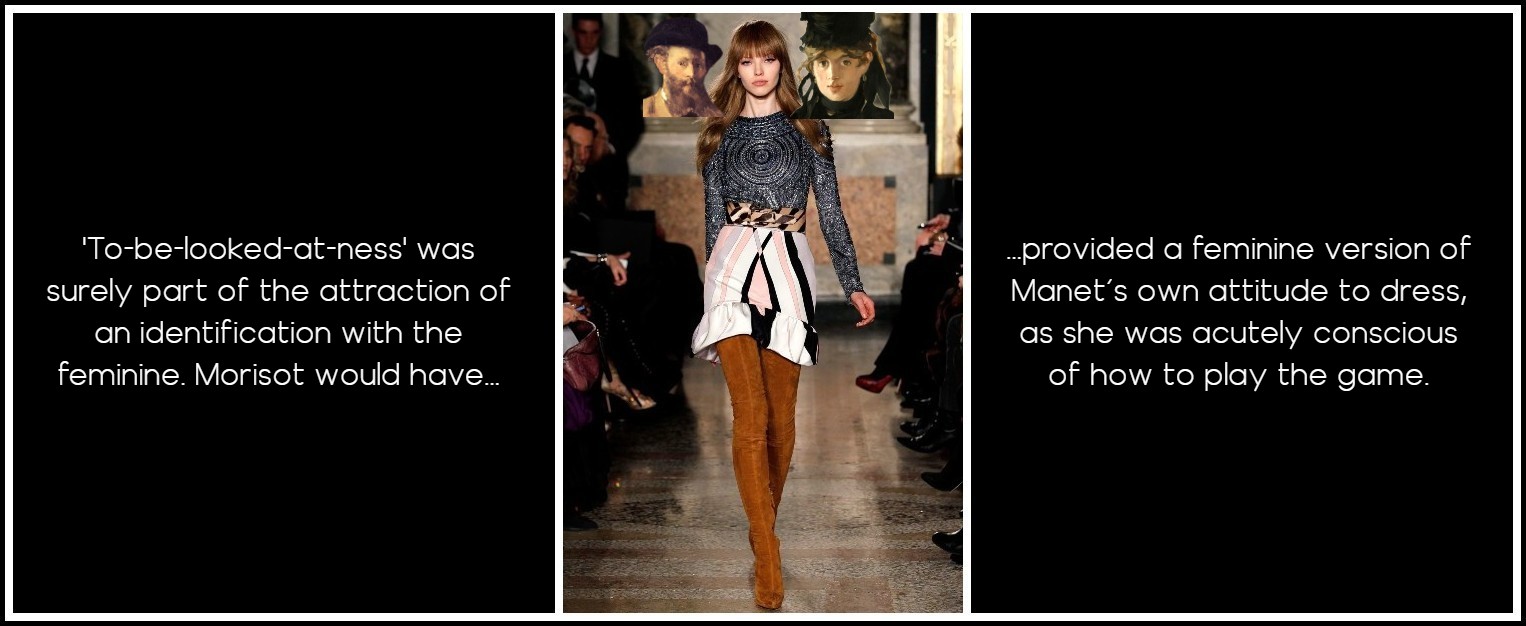

If to paint oneself as another is not in this case wholly to be understood as a gender reversal, what then would be involved in the look by the male artist into the eyes of the female one as part of a search of ‘self,’ for identity? Out of the vast territory that might be thought of as women’s experience, and the specific one that was the experience of a woman who traversed into the territory of the (male) art world, what was selected, what would have constituted that identification? For one, ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’ was surely part of the attraction of an identification with the feminine. The culture of commodified femininity Carol Armstrong explores in Manet’s late work is ample evidence that Manet was attuned to this world. It can be said to be such an integral part of the social construction of ‘woman’ that most women took it for granted. Even a woman who did serious creative work and wanted it seen on its own terms, like Berthe Morisot, accepted the culture of to-be-looked-at-ness as a given. Witness what happened when she found herself in a culture somewhat foreign to her own: among the Franco-Spaniards in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, she felt virtually invisible: Heaven knows here I don’t have to protect myself or be afraid of admirers. I am surprised at being as unnoticed as I am; it is the first time in my life that I am so completely ignored. The advantage of it is that since no one ever looks at me, I find it unnecessary to dress up. Morisot expected to be looked at, and dressed up in anticipation of it. Unlike the model who was paid to undress or wear a costume, a woman like Morisot would have provided a feminine version of Manet’s own attitude to dress, as she was acutely conscious of how to play the game.

Sasha Luss, Emilio Pucci 2013 | Composite: RJ

Yet the fashions and plays of looking, the lifting of hems and the peeking through fans had its limits in the sittings. No matter how subtle the language of fans, corsages, and jewels decoded by the Baronne Staffe and her ilk, the book was only open in the drawing room, with others present; the language runs out when private doors are closed. In that sense, the woman of social standing like Berthe Morisot could practically symbolize, or represent, the constraints that surrounded Manet’s own life. Her very self-presentation as a society woman made those constraints palpable. It is the nature of a concern with social appearances to defer to the judgments of others. Indeed, behind a concern with appearances is a perpetual voice-over of the opinions and judgments of society. To look for oneself in the eyes of another is sometimes to find only the self in others’ eyes—that is, only what others think. The nineteenth-century woman, whether she acknowledged it or not, was expert on the subject; that was perhaps part of the appeal of particular women as models for Manet. Morisot was unconventional in that she was an artist; she represents not the deliberate flouting of mores that a model or prostitute would stand for, but rather a defiance that lurked deeper, under the surface of the cosmetics, the beribboned hats, the fashions. She could stand for a defiance that was genuine, one of spirit and ambition, but also ultimately one of compromise with appearances and surface respectability. In her, Manet could see the extent to which his own life also remained one of deep defiance and surface respectability.

Manet, Portrait of the Artist (Manet with Palette), 1879 (detail) | Manet, Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, 1872

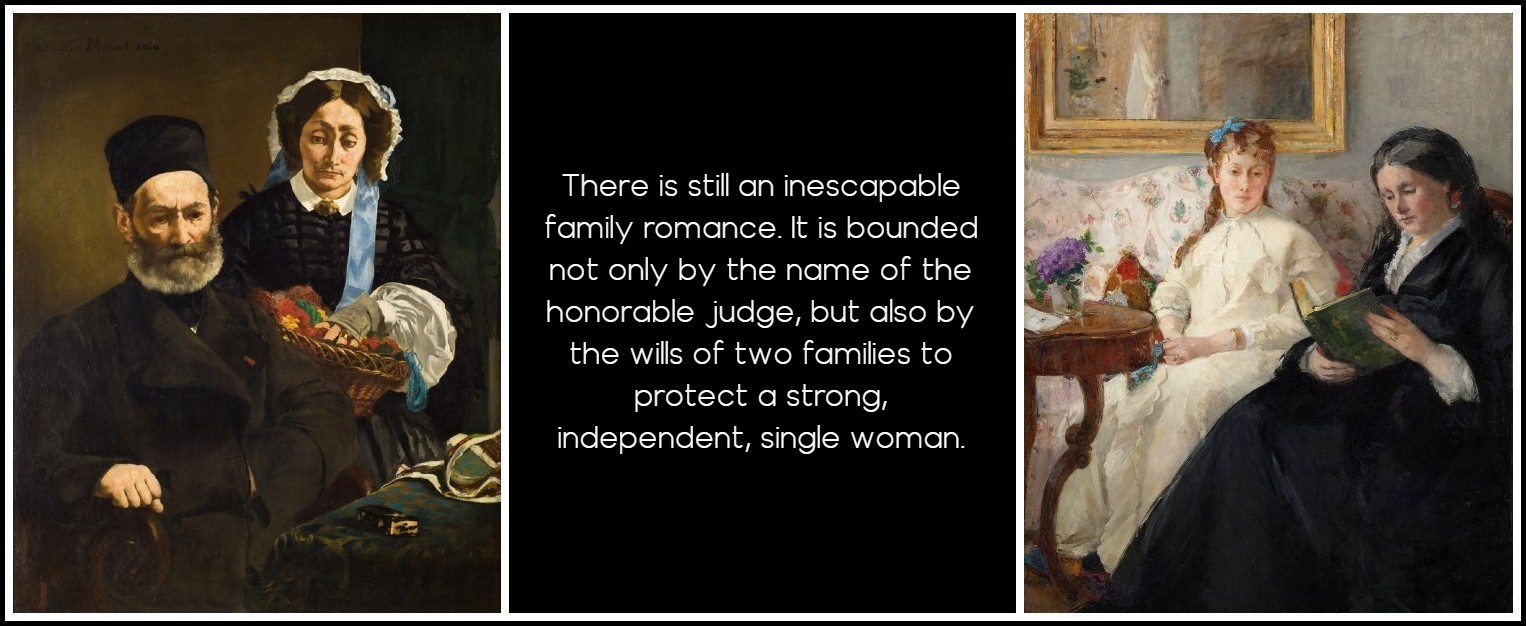

Every act of painting is at some level an attempt to constitute the self. It is an act of facing countless points of resistance, from the pressure of prior masters to that of peers, rivals, friends, family. It is an encounter with these influences and anxieties even while one attempts to make a mark, to paint a face or a street or a flower. For Manet, every act of painting was grounded in resistance to everything for which his family name stood: there was the authority of the judge, the property, the income, the receptions, tradition, the family honor. Manet took on all this in many ways. It is an obvious affront to align oneself with Baudelaire and paint the chiffonniers and the street singers, or to take on Raphael and Giorgione in cheeky parody. But it is also flirting with disaster to paint Berthe Morisot allowing the hem of her skirt to ride up her leg. For every picture of Morisot that toys with such conventions of morality, there is another like Le Repos that is utterly constrained by them. The sartorial freedom Morisot alternately demonstrates and censors (or encourages Manet to censor) emblematizes the process by which the gaze of Others—of society—objectifies the subject (Morisot or Manet). There is still an inescapable family romance; it is bounded not only by the name of the honorable judge, but also by the wills of two families to protect a strong, independent, single woman.

Édouard Manet, Monsieur et Madame Auguste Manet, 1860 | Berthe Morisot, The Mother and Sister of the Artist, 1870

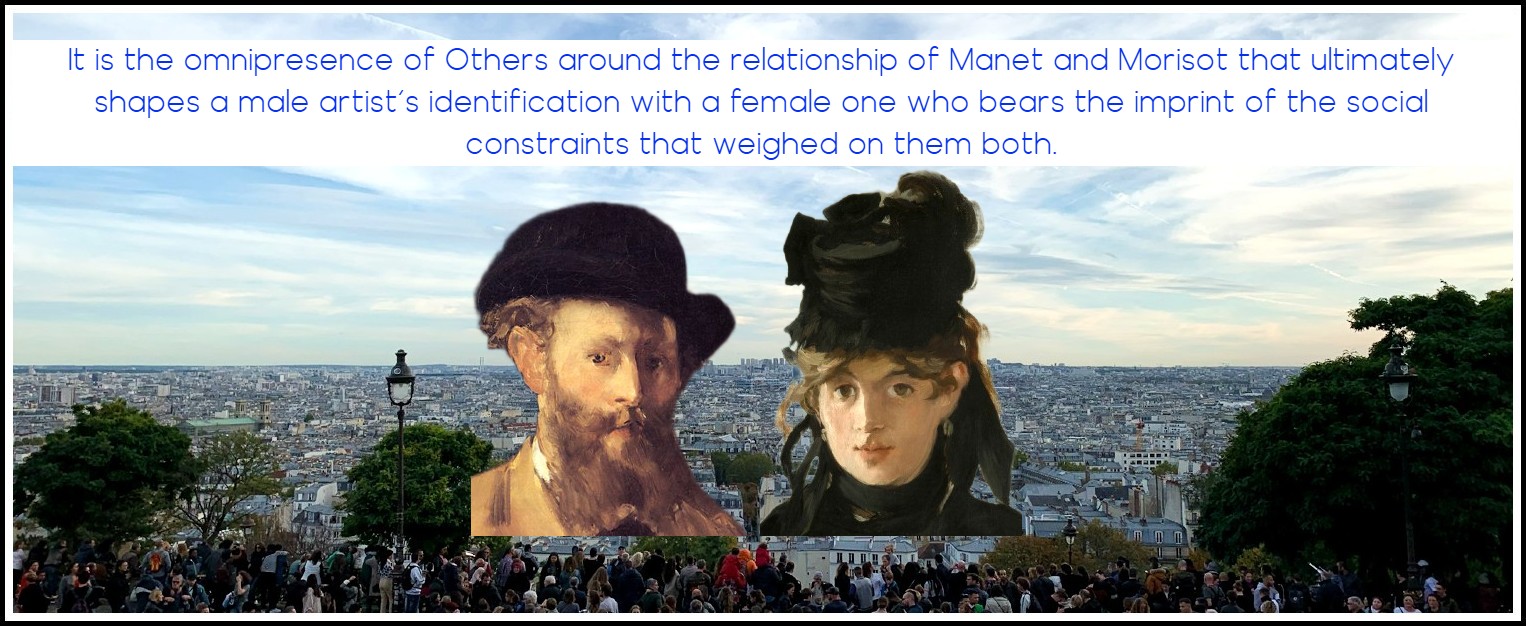

It comes down to what happens in the act of looking. The (male) artist looks at the (female) model: in the example of Manet’s paintings of Morisot, two haut-bourgeois artists look at one another. Any way one puts it, the dice are loaded: looking is not neutral. In this instance, however, one cannot speak of a conventional case of power residing on the side of the upper-class male artist; what takes priority instead is the gaze of Others looking in on the artist, a gaze that thrusts the artist into the position of object. As Sartre put it: ‘By the mere appearance of the Other, I am put in the position of passing judgment on myself as on an object, for it is as an object that I appear to the Other.’ It is the omnipresence of Others around the relationship of Manet and Morisot that ultimately shapes a male artist’s identification with a female one who bears the imprint of the social constraints that weighed on them both.

Photo: Mathieu Viet, Unsplash | Composite: RJ

It would be all too easy to try to suggest that Manet’s portraits of Berthe Morisot are about desire. But to do so would also be to maintain that in that desire—Manet’s or Morisot’s, fulfilled or unfulfilled—lies the truth of the works, their claim as representations of a world. The world they represent is the private domain of two artists with the leisure to pursue poses with fans and pink slippers, and the confidence to make innovative and compelling pictures out of them. It is also a world in which desire was entertained and probably kept at bay. Desire has a way of fixing identity, as Michel Foucault observed, whereas pleasure has ways of blurring it. Foucault maintained that the liberation of desires would not lead to more freedoms; the exploration of more pleasures, however, would. Sometimes a loss of identity is desired, as is an avoidance of desire. The extent to which Morisot and Manet created a domain of pleasures made of reimaginings of identities via the aesthetic materials of clothing, makeup, and paint may be as radical, and as free, as their art ever got.

Photo: Laark Boshoff, Unsplash | Composite: RJ

NANCY LOCKE: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments