The Primitive of Everyone Else’s Way

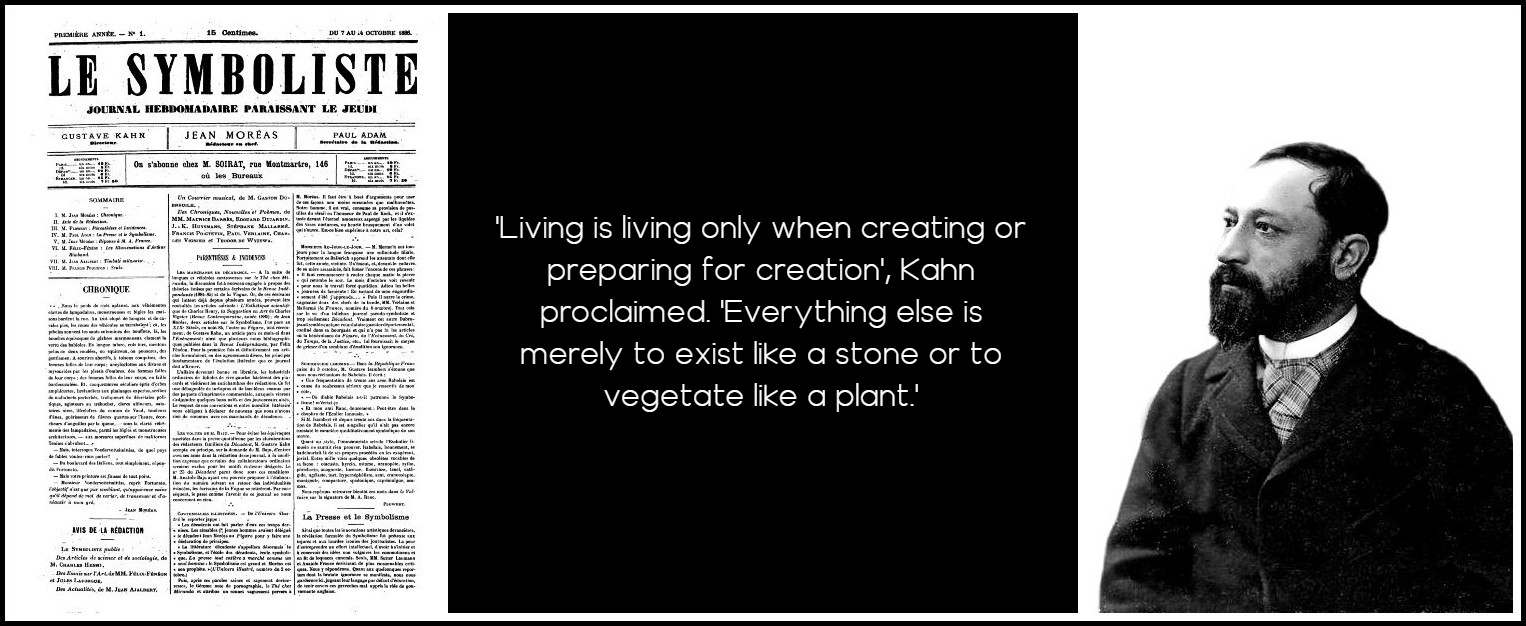

GAUGUIN, CÉZANNE, THE PRIMITIVE AND SYMBOLISM – PART 2

Richard Shiff

Posted by kind permission of Richard Shiff, Effie Marie Cain Regents Chair in Art at The University of Texas at Austin; Director of the Center for the Study of Modernism.

From Richard Shiff, ‘The primitive of everyone else’s way’ in Gauguin and the Origins of Symbolism, editor Guillermo Solana

(London: Philip Wilson Publishers in association with Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza and Fundación Caja Madrid, 2004) 71-79

THIS IS PART 2 OF THE ESSAY. READ PART 1 FIRST.

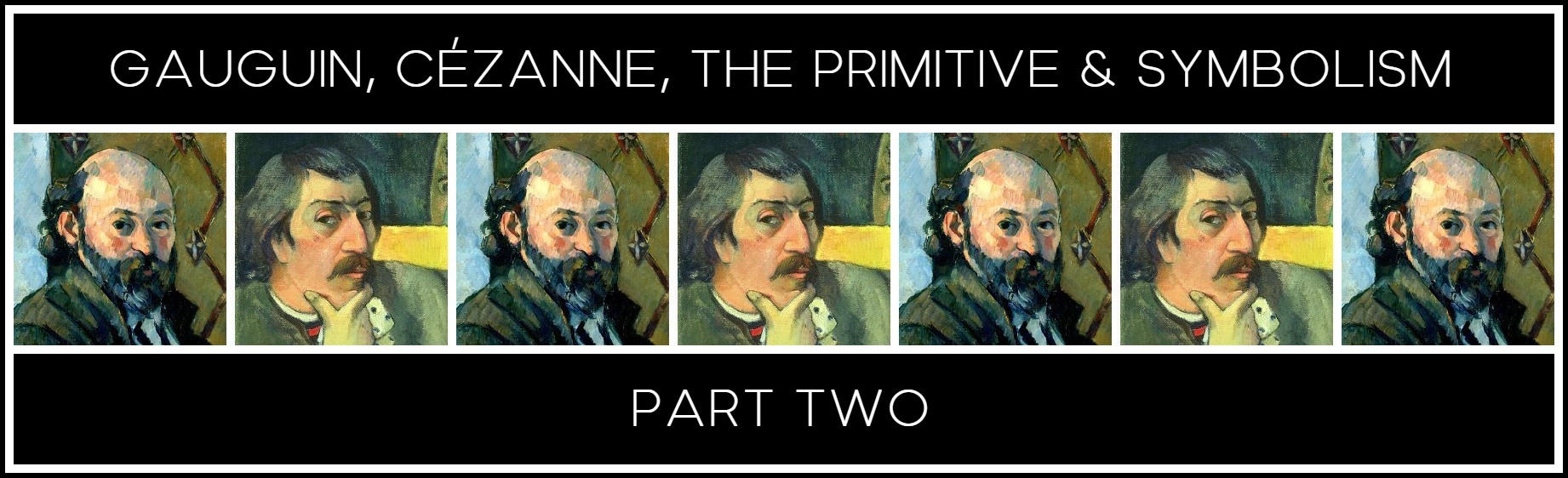

Gauguin was no Pissarro. Although sympathetic to the class that socialists knew as ‘the people’—agricultural labourers, fishermen, machine workers, washerwomen—Gauguin never identified with them. He was an artist: a poet, yet not a literary man. Pragmatic and often engaged with social causes, he nevertheless entertained a rather romanticised view of the plight of the modern artist within an unaccepting bourgeois society. Resistance from the likes of Pissarro and Mirbeau—both socialist-anarchists who on occasion supported him—only reinforced Gauguin’s beleaguered attitude. He was at odds with the world, often rejected by the very people who should have understood him, the sophisticated, free-thinking painters and writers. He knew that his life would be hard, for creativity was not his society’s reigning quality. Like Vincent van Gogh, Gauguin saw himself as an outsider, even an outcast, isolated—but isolated by willful choice and temperament, un isolé (as Aurier referred to both van Gogh and Gauguin).

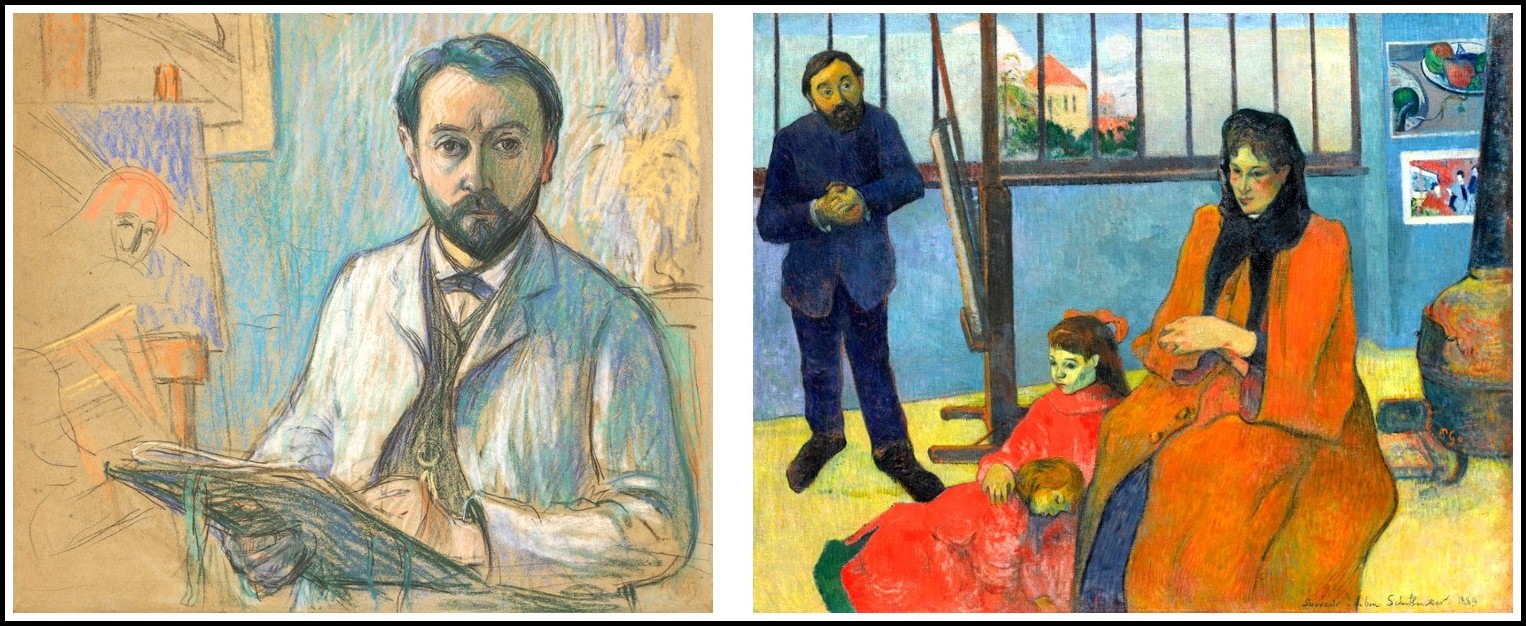

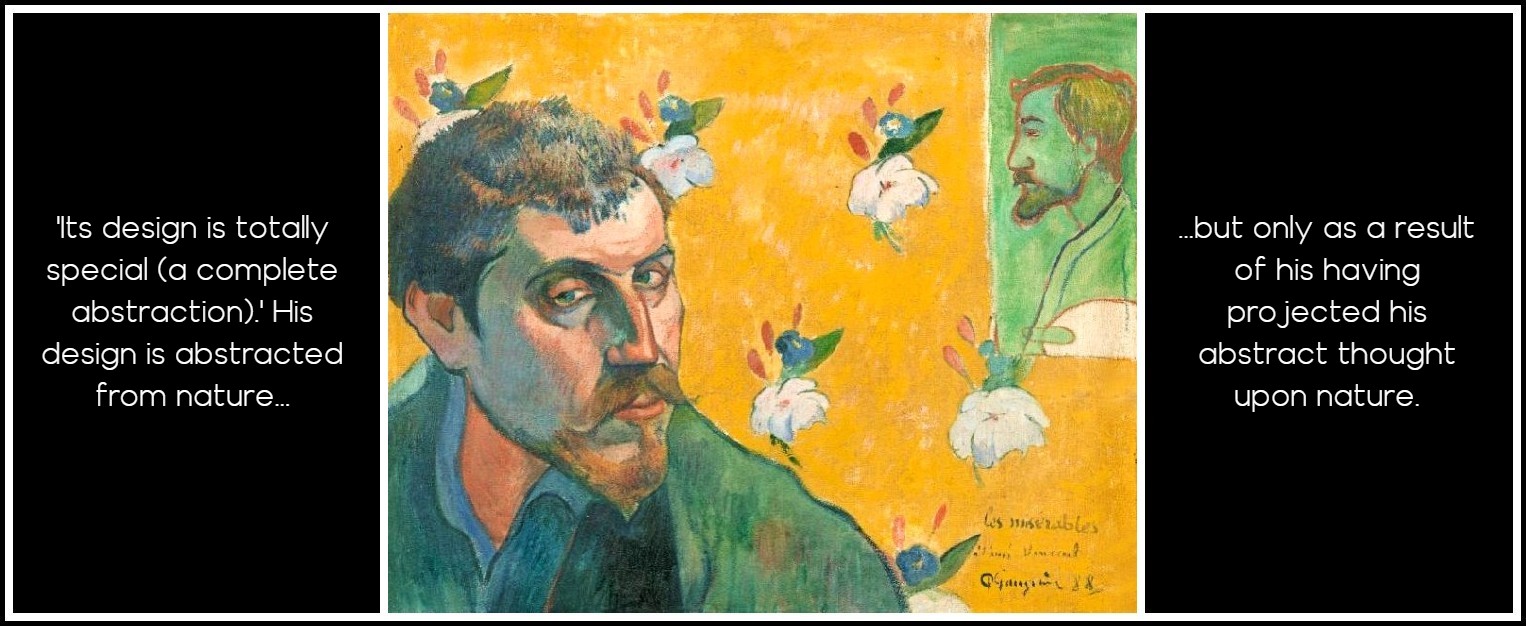

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait (for Paul Gauguin), 1888 | Gauguin, Self-Portrait with Portrait of Emile Bernard (Les misérables, for Vincent), 1888

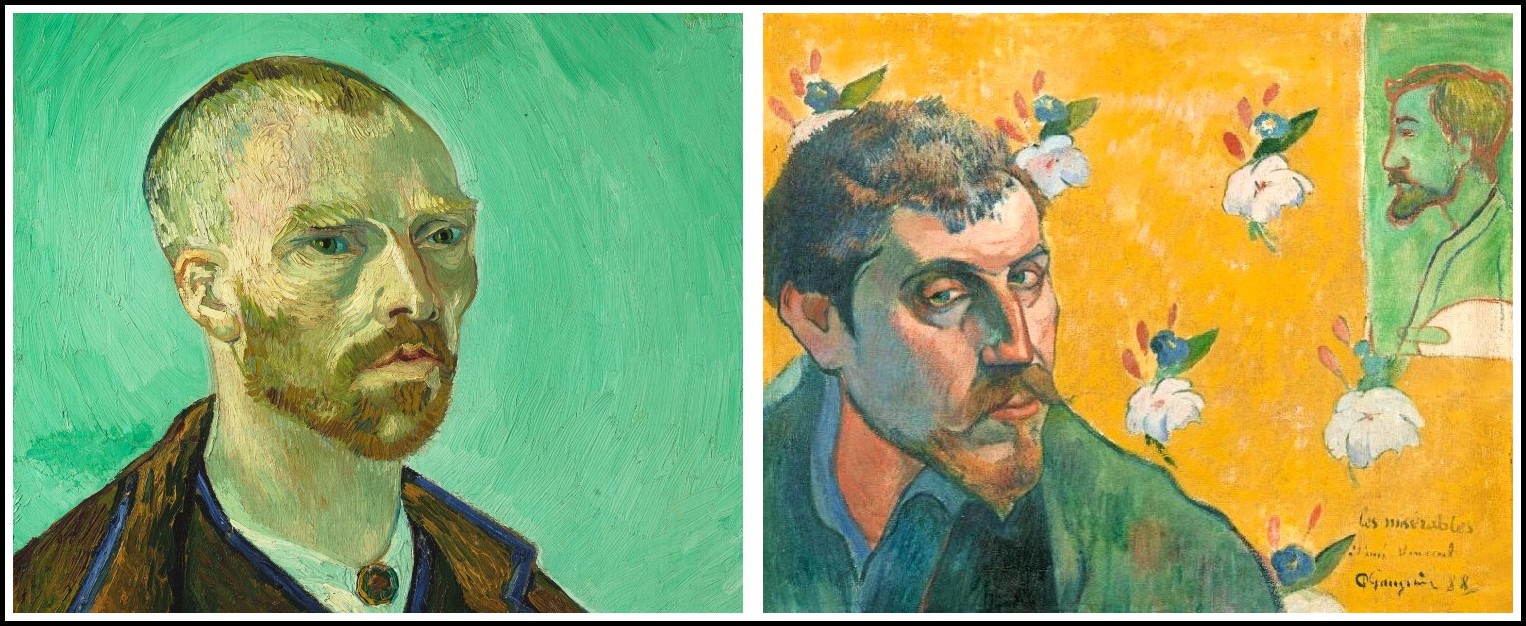

Circumstances nevertheless may have turned out even worse than Gauguin expected. During his final years in relative neglect in Oceania—‘overcome by misery and beset by premature aging’ (his own description)—he had little hope of gaining general recognition or comprehension. ‘With a few words I can explain my painting to you’, he told Morice in 1901, acknowledging the writer’s refined intelligence, ‘but, with regard to the public, why should my brush, otherwise free of all restraint, be obligated to open everyone’s eyes?’. Gauguin’s art required its viewers to be willing to experience ‘emotion first; understanding afterward.’ It was indeed hard to go on living, at least for those like him, wild primitives among the pacified urbanites and colonials who believed that they understood everything already, and therefore resisted all new feeling. In 1891 Aurier referred to such a world as ‘our imbecilic society of bankers and engineers’. When he made this complaint, it was already a cliché; and in 1901, when Gauguin wrote to Morice from Tahiti, it was still more so.

Eugène Carrière, Portrait of Charles Morice, 1893 | Gauguin, Self-Portrait, 1896

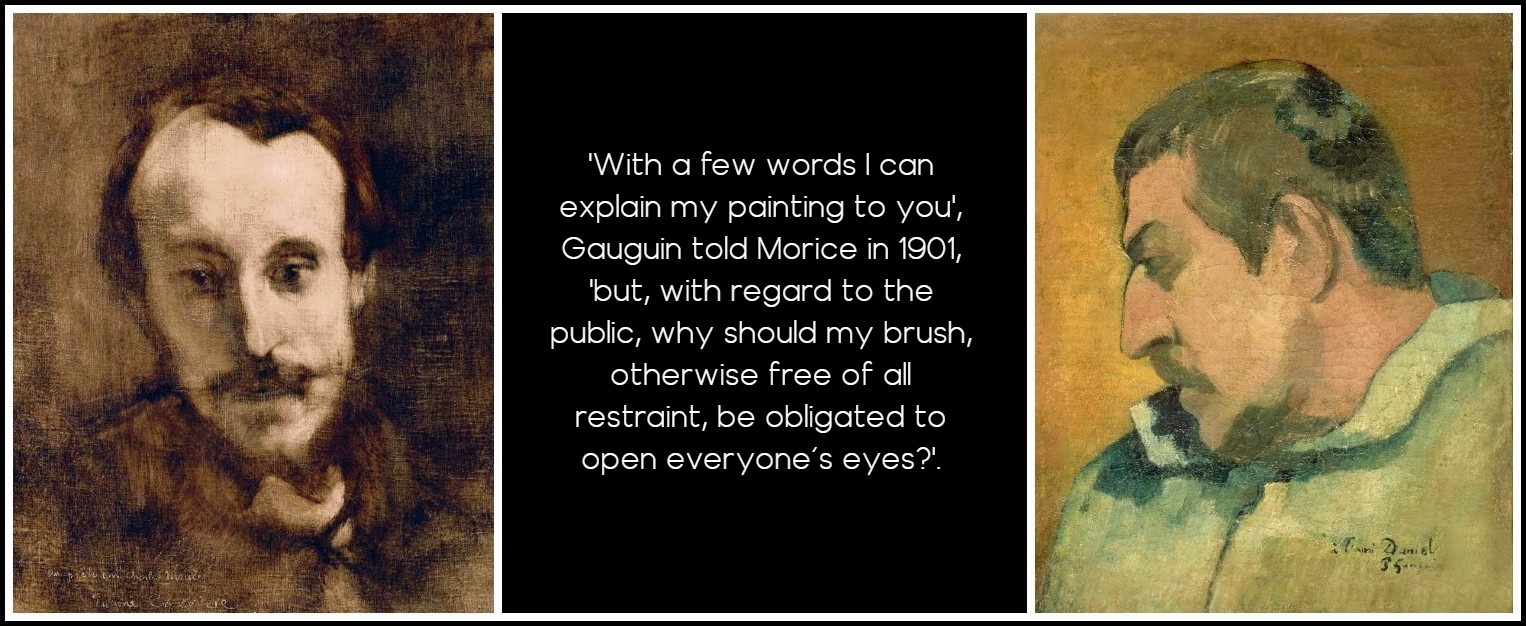

Gustave Kahn, a literary acquaintance of Gauguin (but not one of his advocates), used ‘Difficulty of Living’ as the title of an essay for the second issue of Le Symboliste, the journal he directed. What caused the presumed ‘difficulty’? ‘Living is living only when creating or preparing for creation’, Kahn proclaimed. ‘Everything else is merely to exist like a stone or to vegetate like a plant.’ The organisation of modern society, the writer suggested, offered a plan for surviving rather than for living; it produced the passivity and monotony of a stupefied, stone-like existence. Neither the science of the Academy, nor the economics of the State, nor the religion of the Church, but only art would remedy the urban ills brought by bourgeois society. ‘The aristocracies are gone’, Kahn noted, ‘and their descendants have only their arms, the hunt, horsemanship, mere pastimes.’ An ascendant bourgeoisie ‘imposes its sense of tactful conduct and good taste. Its triumph is stagnation.’ ‘With ‘financial matters’ as the single topic taken seriously, bourgeois conversation became ‘a steady flow of anodyne pleasantries’. As for the working class, it was suffering from ‘a diet of intoxicants and the depression resulting from the monotony and degradation of mechanised labor.’ Kahn published this barrage in October 1886, the month in which Gauguin completed his first campaign of painting in Brittany. There he had been seeking his ‘primitive’ way, stimulated by lingering thoughts of Cézanne and the customs and artifacts of the rude Breton culture, so different from what he experienced in Paris.

Front page of Le Symboliste, 7-14 October 1886 | Gustave Kahn (Photo: Henri Manuel)

III. TO ABSTRACT, TO ISOLATE

Statements by French artists and critics active during the last quarter of the nineteenth century make frequent use of the words abstraire (to abstract), abstrait (abstract), and abstraction (abstraction), as well as, occasionally, s’abstraire (to become mentally abstracted, or to withdraw or isolate oneself). These terms convey the sense of a circumscribed reduction—the isolation, but also intensification and concentration, of a form or a feeling. Writing from Brittany in August 1888, Gauguin advised fellow painter Emile Schuffenecker: ‘Art is an abstraction; draw it out from nature in dreaming before nature, and think more of this act of creation than of what will result.’ With his reference to dreaming, Gauguin alludes to a kind of wakeful, but abstracted, projection of his thoughts upon the surrounding environment. As he told Morice in 1890: ‘Primitive art originates in the mind and puts nature to its use.’ Projective dreaming allowed Gauguin to ‘see’ his world poetically, taking from it—drawing from it, extracting—the core of its suggestiveness. A particular colour might evoke the emotionality (Aurier’s émotivité) associated with a particular object; but such colour would not derive exclusively from the object, for it would exist as well in the eye and mind of the artist. When Gauguin viewed his model in nature, he projected its image, which was his dream.

Emile Schuffenecker, Self-Portrait in the Studio, 1889 | Paul Gauguin, Schuffenecker’s Studio, 1889

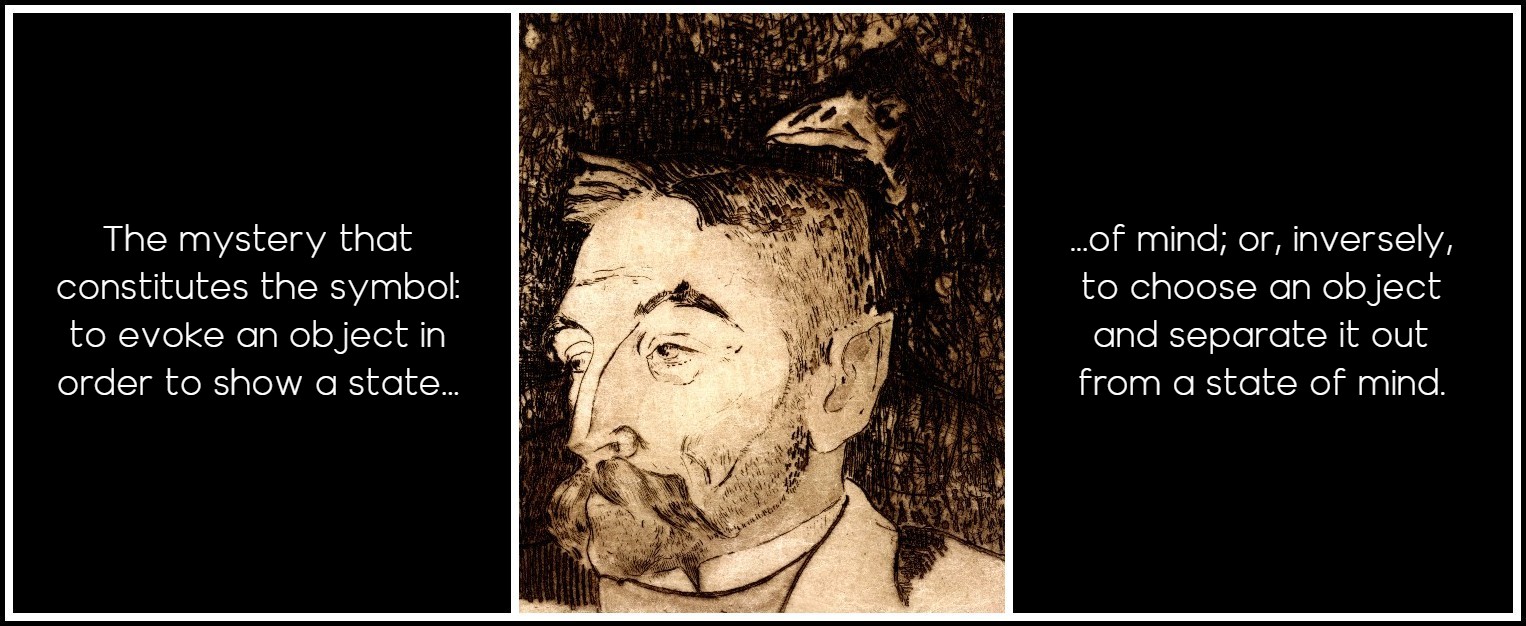

As a theorist, Morice wrote about the power of this kind of ‘suggestiveness’. He was no doubt inspired by his mentor Stéphane Mallarmé who, despite accusations of obscurity, spoke of the reciprocity of the symbol with remarkable clarity. Here are Mallarmé’s words from an interview of 1891: ‘To suggest (the object), there you have the dream. This is the perfect use of the mystery that constitutes the symbol: gradually to evoke an object in order to show a state of mind, or, inversely, to choose an object and, by a series of decipherments, to abstract (release, separate out) from it a state of mind.’

Gauguin, Stéphane Mallarmé, 1918

By this process of projection and extraction, an artistic image became what Gauguin called ‘an abstraction’. As a drawing-away or drawing-from, abstraction isolates the points of contact between a subject (the artist) and an object (nature). When Aurier referred to ‘the symbolism of the abstract elements of design’, his word abstrait indicated that the expressive factor in visual art could be drawn or separated out, isolated and hence intensified to create a specific emotional and ideational effect. To use a colour without concern for its naturalism (whatever in nature it might resemble) would abstract from the general experience of that colour its specifically expressive, symbolic quality. Gauguin’s kind of abstraction—as opposed to the rule-bound, academic abstraction of ‘official’ art—touched on emotions that lay beyond the intellectual comprehension of ordinary referential language. This is why he told Morice that his viewers needed to experience ‘emotion first; understanding afterward.’ In 1888 Gauguin described the self-portrait he was sending to van Gogh in anticipation of their planned painting campaign in Arles: ‘Its design is totally special (a complete abstraction).’ Here the descriptive term ‘special’ indicates that the form is specific to Gauguin’s thinking, his dreaming. His design is abstracted from nature, but only as a result of his having projected his abstract thought upon nature. His approach to writing was analogous: ‘I wish to write the way I make my paintings, that is, by my fantasy, according to the moon [emotion], and to find the title [understanding] long afterward.’

Gauguin, Self-Portrait with Portrait of Emile Bernard (Les misérables, for Vincent), 1888

Commenting on Gauguin’s art after his return from Tahiti in 1893, Morice gave a de facto description of the process of abstraction, the act of creation of which Gauguin had advised Schuffenecker from Brittany, five years previously: ‘With incredible rapidity, a painter’s brain projects its thought upon the view—whether a person’s face or a landscape—and to reclaim this thought, to extract it from the spectacle, painters cut away, simplify, synthesise, eliminating everything that would interfere with a plain vision of the object. Try to recognize in an objective view of nature the landscape where Gauguin saw only his thought!’ Morice’s commentary corresponds not only with Gauguin’s beliefs but with the writer’s earlier account of Symbolist literature, for which he used examples from painting: ‘If Corot and Cazin “copy” the same landscape, neither will their landscapes resemble each other, nor will one “copied” with the aid of a photographic lens resemble either of the other two—only vaguely. Strictly speaking, no exact description is ever possible. Art is essentially subjective. The appearance of things is only a symbol; the artist’s mission is to interpret it. Things acquire truth only in him, they have only an internal truth.’ We comprehend external reality only as it is abstracted, isolated as an ‘internal truth’ that the activity of an artist creates. Performing the abstraction ourselves, we become artists.

Jean-Charles Cazin, Normandy Village, 1875 | Camille Corot, Souvenir of Coubron, 1872

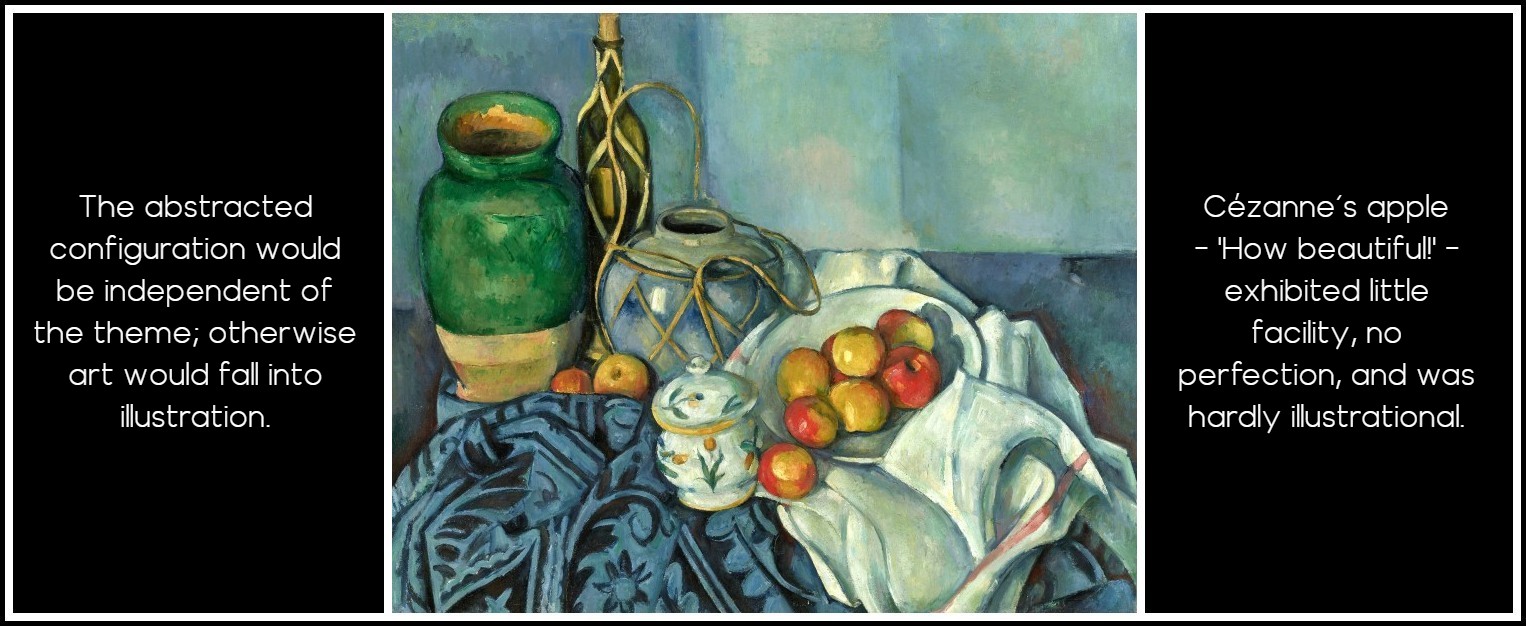

Early in the evolution of his thinking, but already affected by Gauguin, Sérusier stressed the element of personality in his exposition of a Symbolist aesthetic. This factor was usually called ‘temperament’ by naturalists, but they too sometimes referred to personality. Regardless of which word was used, both naturalists and Symbolists shifted the sense of personality from a limited array of human types to an unlimited set of individuals. Given Morice’s account, personality or temperament would explain the difference between landscapes by Corot and Cazin; each necessarily expressed something of his individuality, even when dealing with a general truth. In October 1889, Sérusier wrote to Denis: ‘Personality in art is an abstract thing.’ With his phrase une chose abstraite, he implied that every personality escaped concrete definition. Personality could not be developed in a professional atelier, as if it were an effect to be cultivated by the flourishes of a brush. In fact, the more an artist neglected manual facility, the more evident the element of personality might become, even as maladroitness increased. ‘Given a certain amount of lines and colours that form a harmony,’ Sérusier reasoned, ‘there is an infinity of ways of arranging them.’ Personality would determine which configuration out of the many harmonious ones—which specific form abstracted from the general field of aesthetically satisfying forms—would appear as the artist’s projection of the scene or theme. Yet the abstracted configuration would be independent of the theme; otherwise, Sérusier warned, art would ‘fall into illustration’. Cézanne’s apple—‘How beautiful!’—exhibited little facility, no perfection, and was hardly illustrational.

Cézanne, Still Life with Apples, 1894

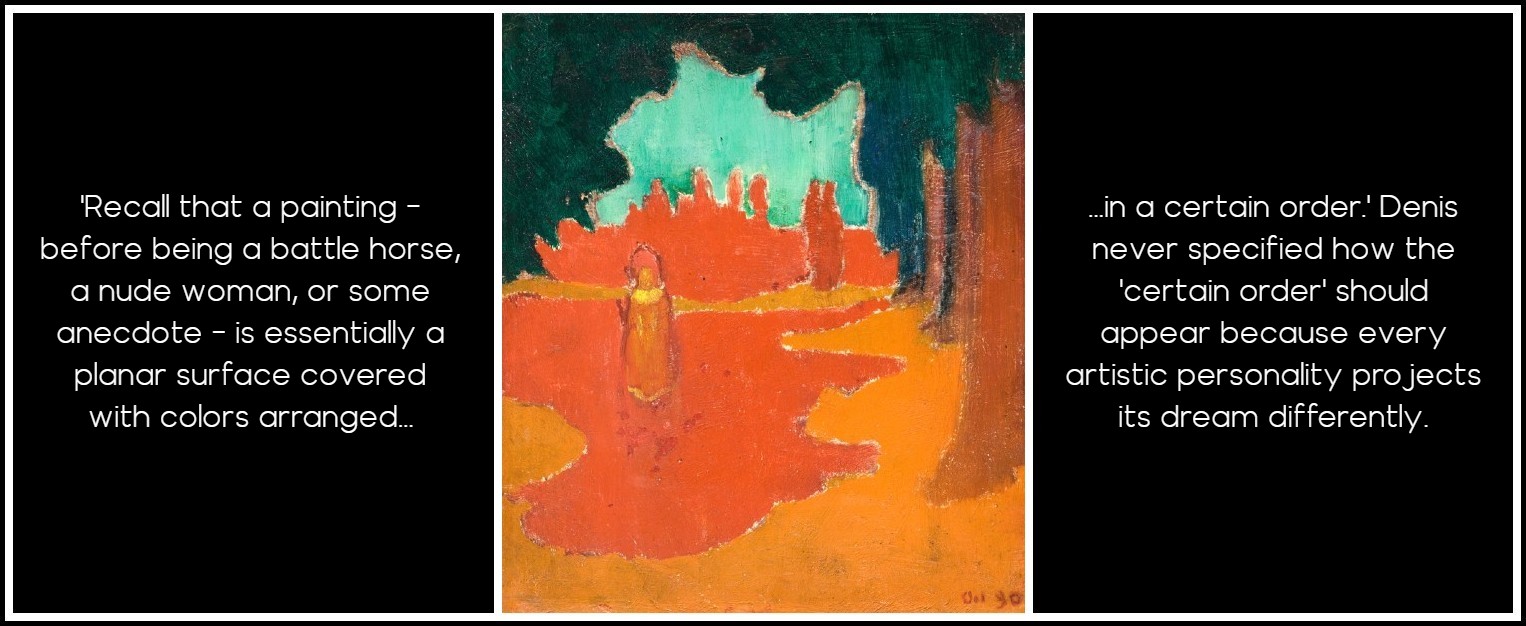

Less than a year after Sérusier formulated his thoughts, Denis published his own Gauguinesque definition of painting, which has often been regarded as a theory—fifteen years before the fact—of twentieth-century formalist and abstract art (see Denis, Patches of Sun on the Terrace (1890). With his simple qualifier ‘certain’, Denis incorporated Sérusier’s notion of infinitely varied personality: ‘Recall that a painting—before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote—is essentially a planar surface covered with colors arranged in a certain order.’ Denis never specified how the ‘certain order’ should appear because every artistic personality projects its dream differently. An artist’s colours (the abstracted material factor) express the artist’s thought and vision (the abstracted psychological factor). The result might prove to be either universalising or isolating.

Maurice Denis, Patches of Sun on the Terrace, 1890

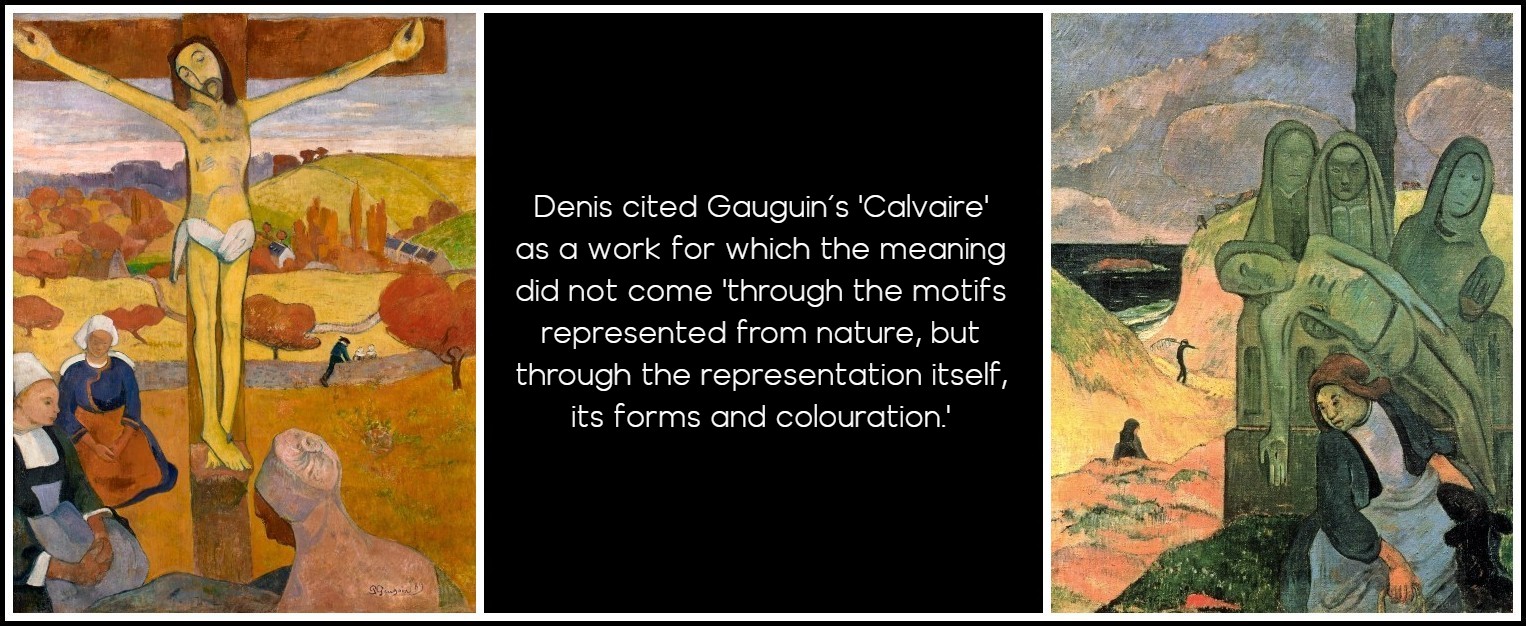

In his essay of 1890, Denis cited Gauguin’s Calvaire as a work for which the meaning did not come ‘through the motifs represented from nature, but through the representation itself, its forms and colouration.’ This is what many critics were calling Symbolisme; on this occasion, Denis named it Néo-traditionnisme.

Gauguin, The Yellow Christ, 1889 | Gauguin, The Green Christ (Le calvaire breton), 1889

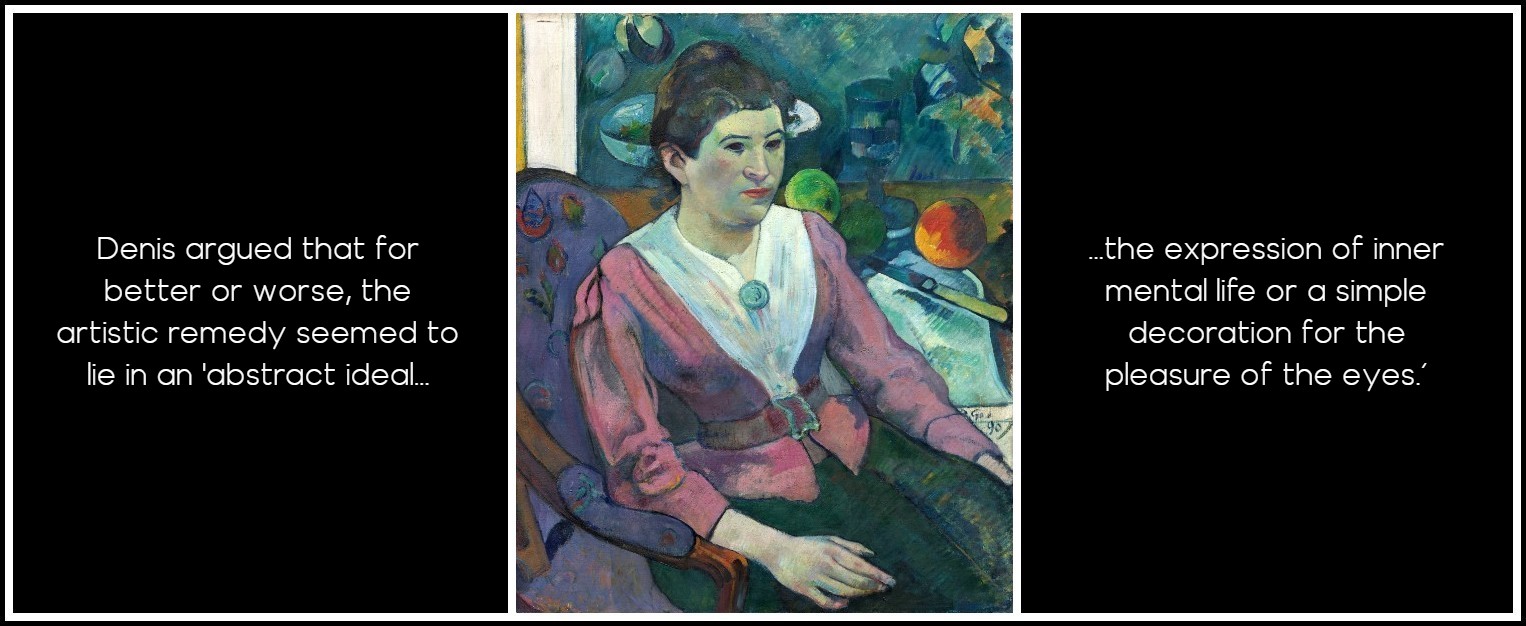

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Denis (like Kahn and Gauguin before him) observed that his society was being dehumanised by the leveling effects of modern urban life—mechanisation, standardization and social regulation—all leading to impoverishment of both intellectual and spiritual experience. Because life was hard, sensitive souls turned to art: ‘We live in the museums, the theatres, the concert halls, amidst the sensations of art: there we gradually lose the sense of real life; our sensibility increasingly requires purely aesthetic feelings.’ Denis argued that for better or worse, the artistic remedy seemed to lie in an ‘abstract ideal, the expression of inner mental life or a simple decoration for the pleasure of the eyes.’ This ‘ideal’ would assume many material forms, the many different instances of ‘a certain order.’ Cézanne was exemplary because his marks appeared independent of mimetic function and were also aggressively physical, as Gauguin had emphasised in his appropriation of his elder’s primitive way. Cézanne created an emotionally engaged, material abstraction of the painting process. His materialism was aestheticised and humanised, intense in both sensation and spirit; and its energy countered the vegetative character of bourgeois life, its stone-like existence.

Gauguin, Woman in Front of a Still Life by Cézanne, 1890

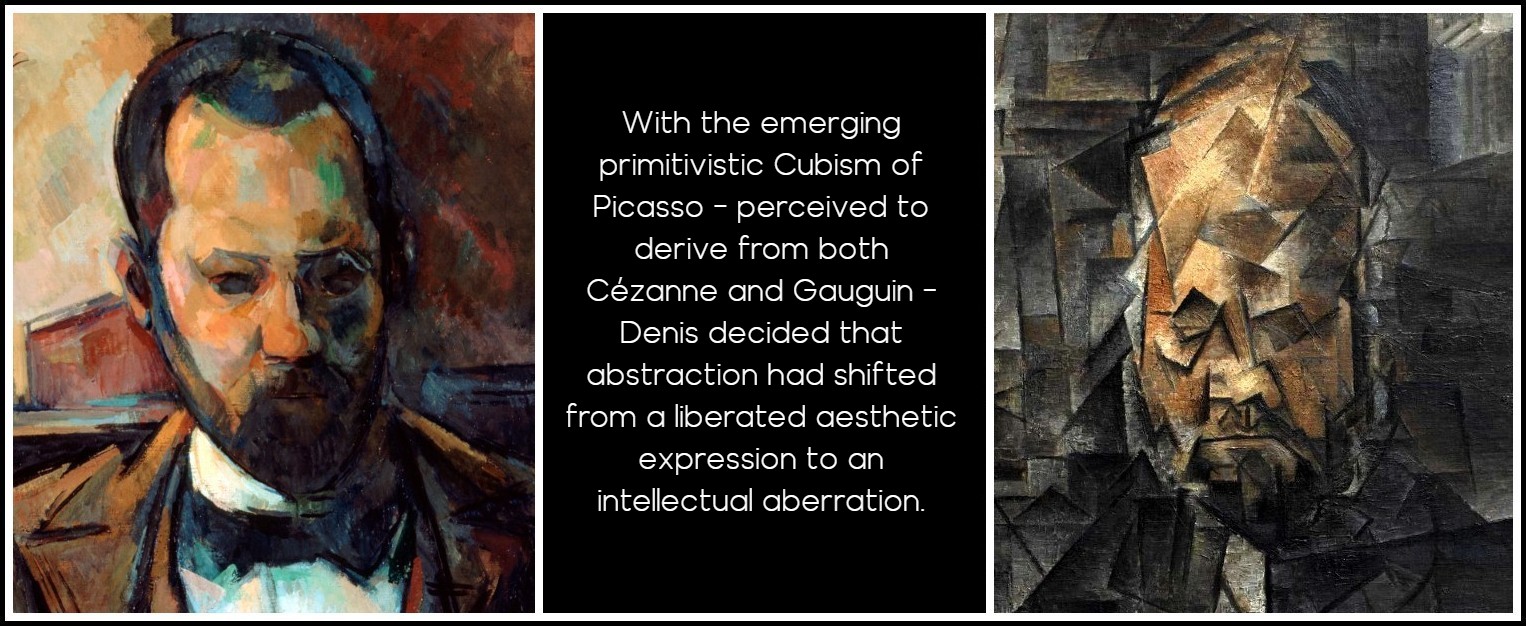

Once manifested as a technique and articulated as a critical principle, material abstraction of Cézanne’s kind had no clear limit, whether physical or conceptual. With the advent of Henri Matisse’s Fauvism and the emerging primitivistic Cubism of Pablo Picasso—styles perceived to derive from both Cézanne and Gauguin—Denis decided that ‘abstraction’ had shifted from a liberated aesthetic expression to an intellectual aberration.

Cézanne, Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, 1899 (detail) | Picasso, Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, 1910 (detail)

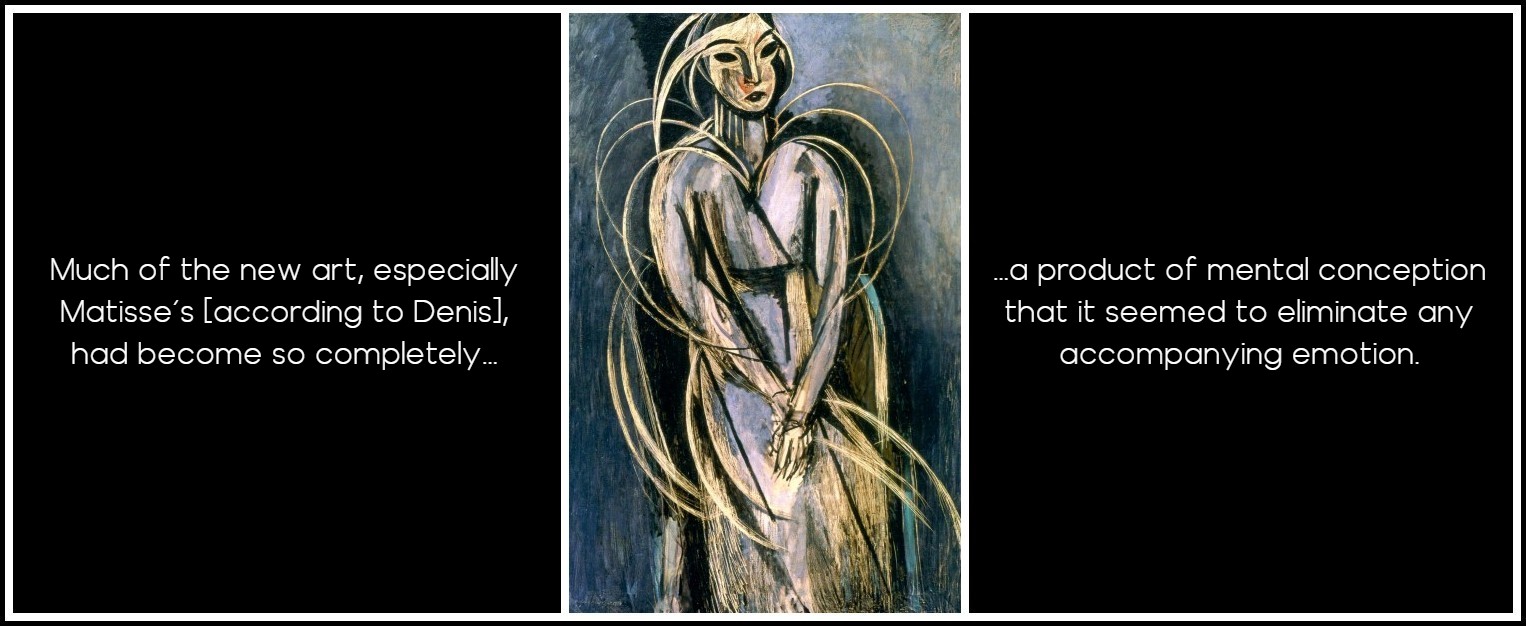

Much of the new art, especially Matisse’s, had become so completely a product of mental conception that it seemed to eliminate any accompanying emotion: ‘Painting apart from any contingency, painting in itself, the pure act of painting, lacking our instinct for nature.’ ‘Abstraction’ and ‘form’ had been pushed so far that neither sensible reason nor human feeling, but only misguided theories, could justify the new practices.

Matisse, Portrait of Yvonne Landsberg, 1914

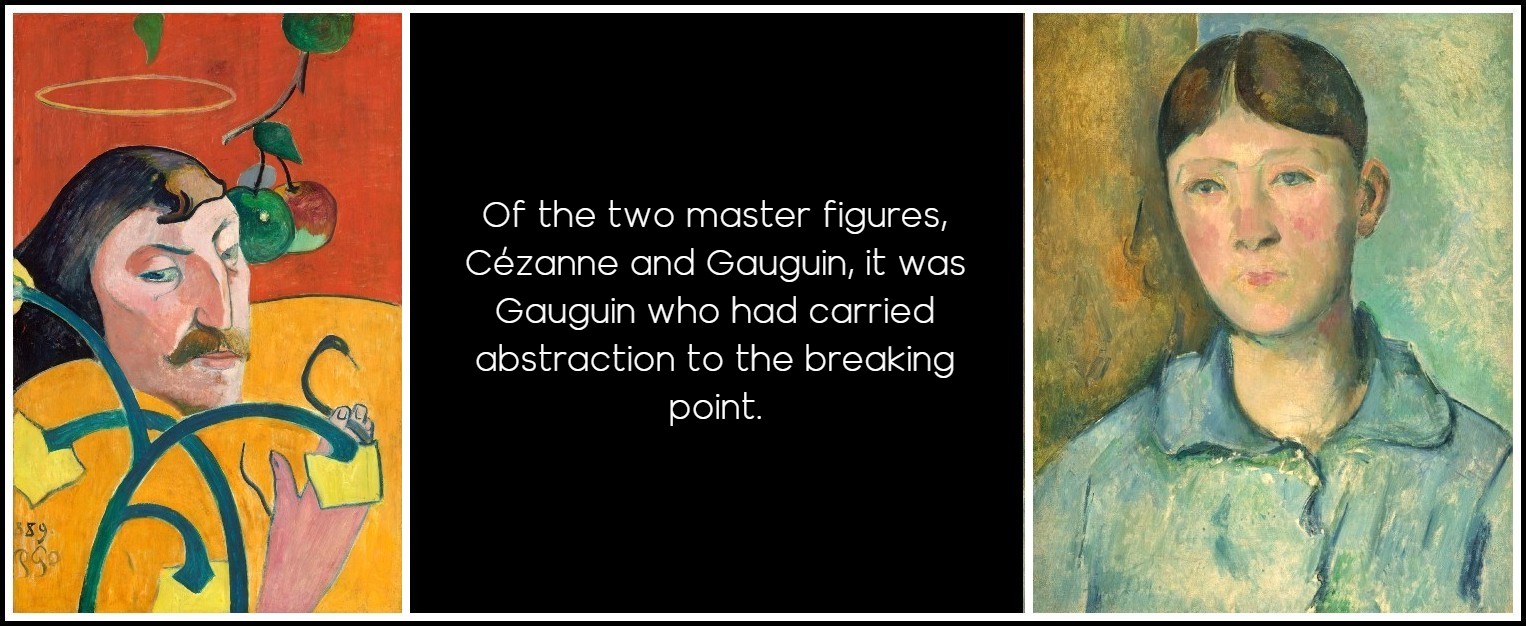

Denis excluded Cézanne from these accusations, explaining that he had never ‘compromised’ his pictorial synthesis with any ‘conceptualised abstraction’; despite its abstraction of the means, Cézanne’s art redeemed itself by remaining rooted in nature. (Recall Pissarro’s complaint about Aurier, that he would induce painting to lose all physicality.) Of the two master figures, Cézanne and Gauguin, it was the latter who had carried abstraction to the breaking point: ‘He rendered Cézanne’s models flat. The reconstruction of art that Cézanne had begun with the materials of impressionism, Gauguin continued with less feeling but more theoretical rigor.’

Gauguin, Self-Portrait, 1889 | Cézanne, Portrait of Madame Cézanne, 1885-1890

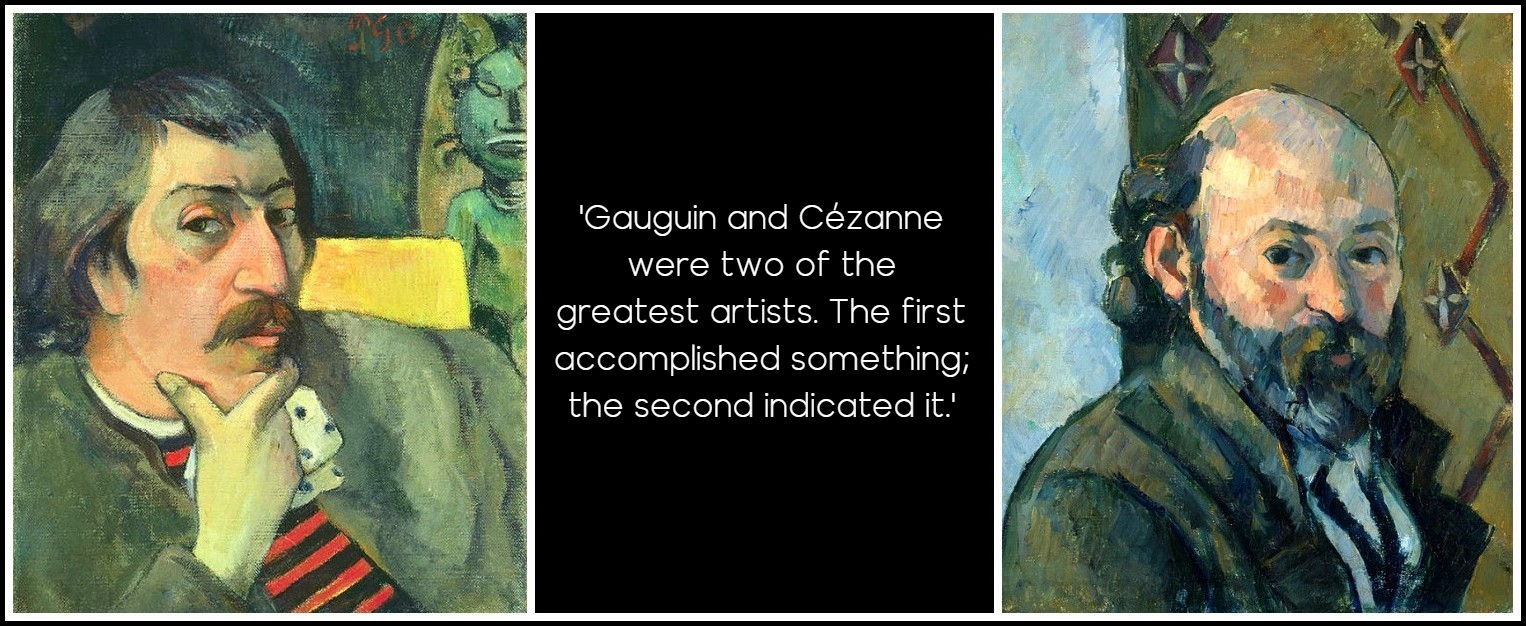

Under Gauguin’s leadership, the art properly called ‘abstract’ had been reduced to a product of theory; it was no longer emotional projection, no longer a liberating dream. Gauguin’s old collaborator Morice was sensitive to this realignment of authority, which critics cited while pitting one modernist hero against the other. Morice urged his colleagues to avoid such partisan division: ‘Gauguin and Cézanne were two of the greatest artists. The first accomplished something; the second [Cézanne] indicated it.’ Against the obstacles that bourgeois society set in the way, Cézanne and Gauguin equally furthered the cause of living.

Gauguin, Self-Portrait with Idol, 1893 | Cézanne, Self-Portrait, 1881

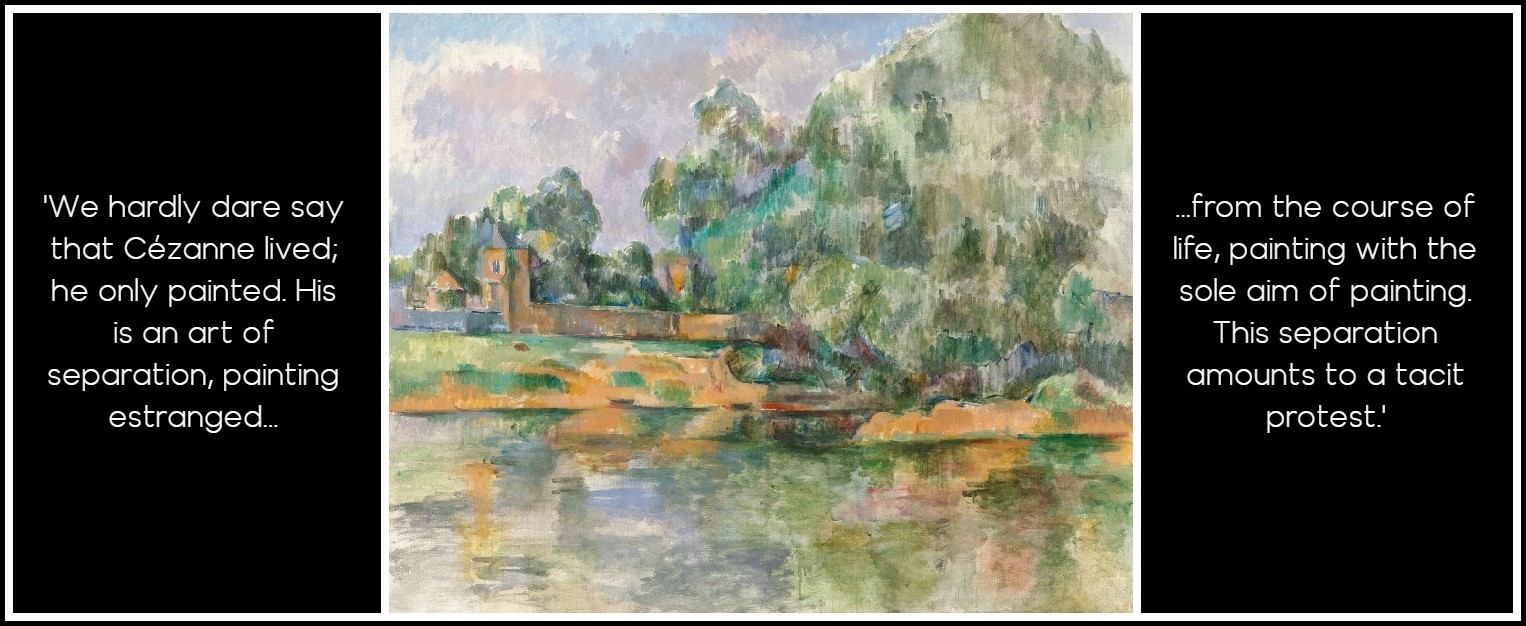

But they were not always such equals, even for Morice who admired them both. If Denis favoured Cézanne over Gauguin, it could be argued that Morice favored Gauguin over Cézanne. He expressed a certain ambivalence toward Cézanne’s cultural and psychological difficulties, not unrelated to the type of reservation Denis felt when he regarded Matisse. Several months after Cézanne’s death, Morice wrote: ‘We hardly dare say that Cézanne lived; he only painted. His is an art of separation, painting estranged from the course of life, painting with the sole aim of painting. This separation amounts to a tacit protest.’ Like Denis, like Kahn, like Gauguin, Morice believed that scientism, materialism and technocratic efficiency were deadening all spiritual life. The situation tempted artists to abandon the decaying remains of humanistic principle and withdraw into pure sensory experience. Cézanne purged his life—a life that amounted to painting, because he had no other life—of all social and ‘moral values’, for which he substituted ‘colour values’.

Cezanne, Banks of the Seine at Médan, 1885-1890

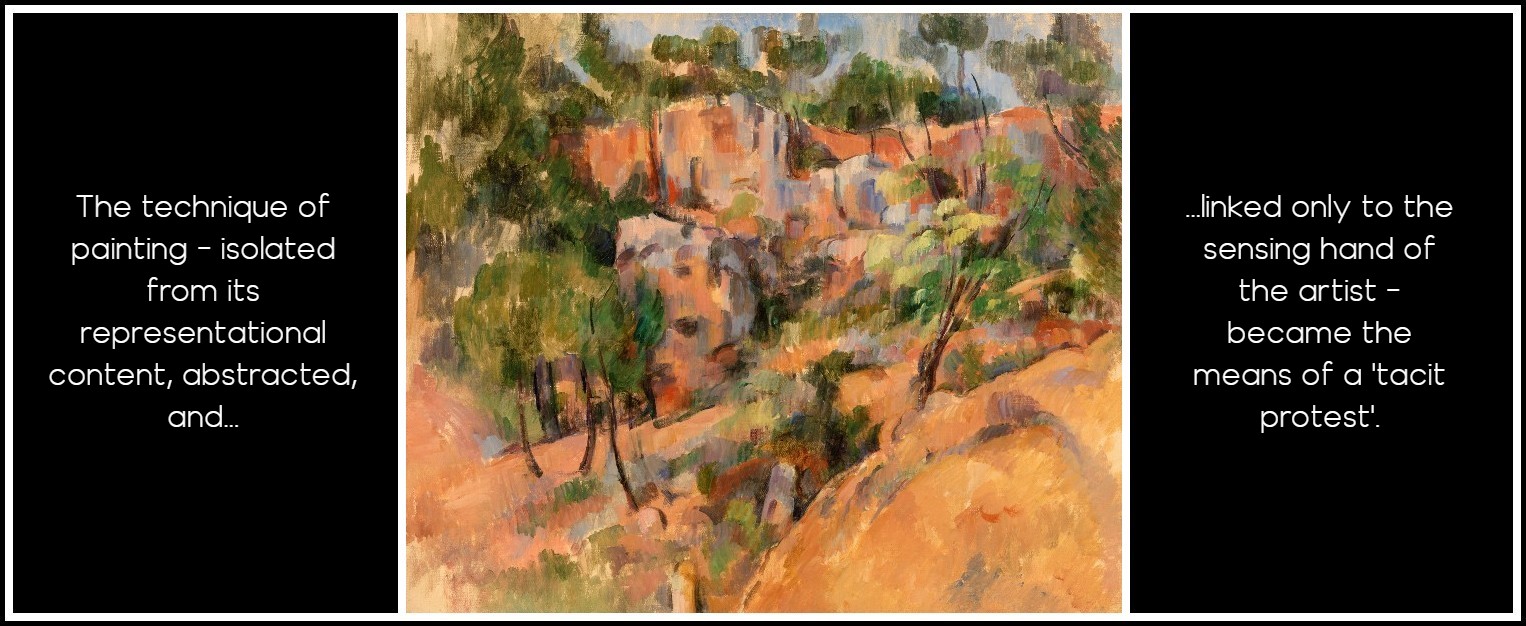

In lieu of intellectual and ethical abstractions, the painter produced colour abstractions. Cézanne did not lack political, religious or philosophical beliefs, but he appeared resigned to the fact that theoretical and ideological concerns could no longer guide his or any other artistic practice. The technique of painting—isolated from its representational content, abstracted, and linked only to the sensing hand of the artist—became the means of a ‘tacit protest’. To the sensitive critic, it signalled the corruption of the intellectual and moral bases of modern society. Acknowledging Cézanne’s impenetrable mystery, Morice added parenthetically: ‘Was his protest fully conscious? I don’t know.’

Cézanne, Bibémus, 1895

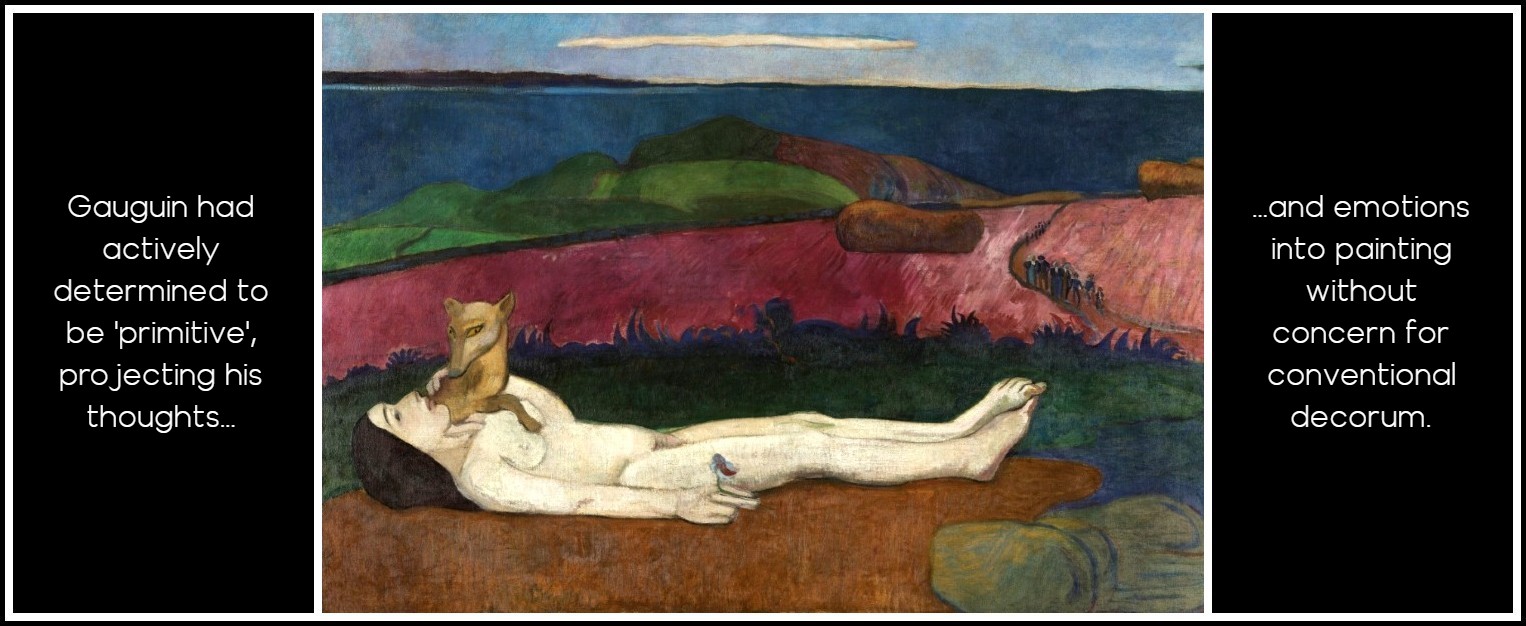

In the case of Gauguin, however, we do know: he understood what he was doing. Morice noted Gauguin’s ability to reproduce an alien style with precision, controlling the influence of his own personality; referring to a related capacity to manipulate, Pissarro called Gauguin a ‘schemer’. With his refined intelligence and precise but intentionally unrefined language, Gauguin could articulate a ‘Symbolist’ position as clearly as Morice, Aurier, Sérusier or Denis. He had actively determined to be ‘primitive’, projecting his thoughts and emotions into painting without concern for conventional decorum.

Gauguin, The Loss of Virginity, 1891

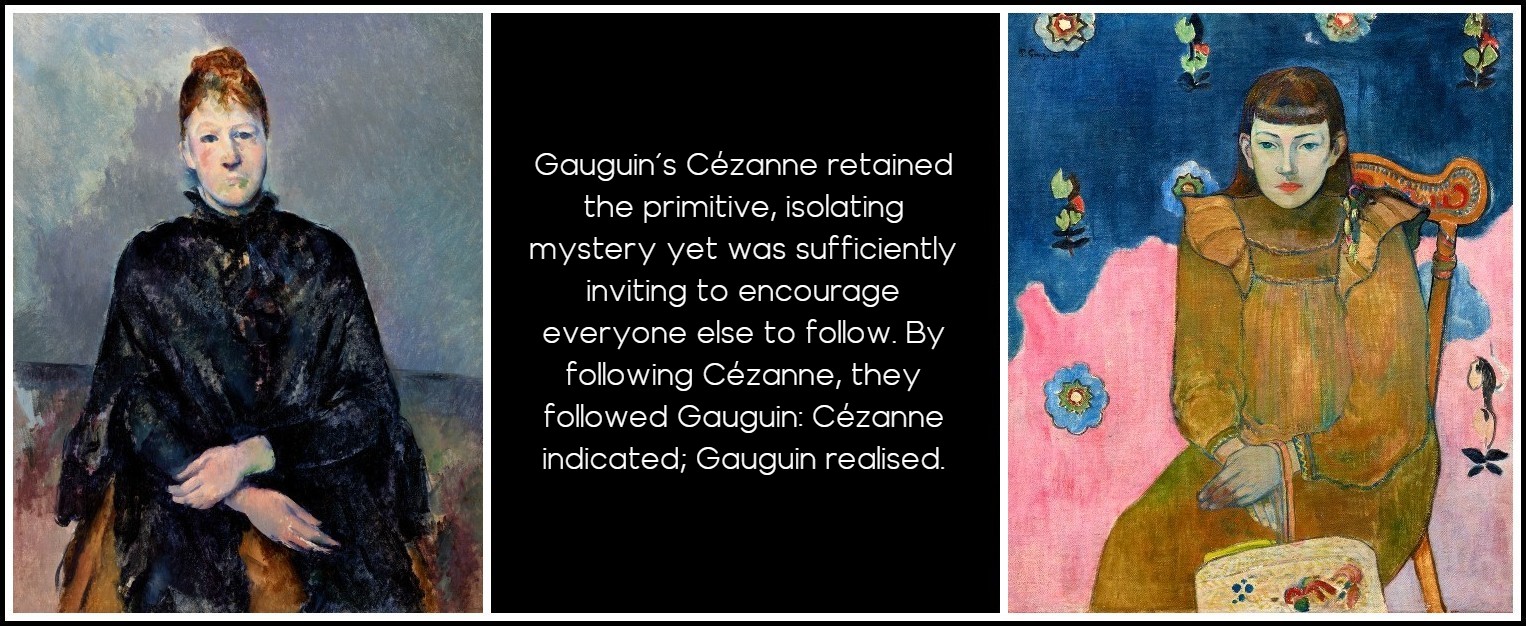

Neither his hard life (self-imposed?) nor his psychological self-isolation prevented him from recognising Cézanne’s radical inventiveness. He abstracted from Cézanne’s way its most meaningful and productive elements. Gauguin’s Cézanne retained the primitive, isolating mystery yet was sufficiently inviting to encourage everyone else to follow. By following Cézanne, they followed Gauguin. In this Morice was correct: Cézanne indicated; Gauguin realised.

Cézanne, Portrait of Madame Cézanne, 1888-1890 | Gauguin, Portrait of a Young Woman (Vaïte/Jeanne Goupil), 1896

RICHARD SHIFF: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments