Orpheus & Eurydice

PART 1: ORPHEUS & ANCIENT ORPHISM | PART II: ORPHEUS & EURYDICE IN ‘MARA; MARIETTA’ | PART III: RILKE: ‘ORPHEUS. EURYDICE. HERMES’

PART I

ORPHEUS AND ANCIENT ORPHISM

Judith Eleanor Bernstock

Posted by kind permission of Judith Eleanor Bernstock, Associate Professor Emerita, History of Art and Visual Studies, Cornell University

From Judith Bernstock, Under the Spell of Orpheus: The Persistence of Myth in Twentieth-Century Art (Southern Illinois University Press, 1991) pp. xvii-xxiii

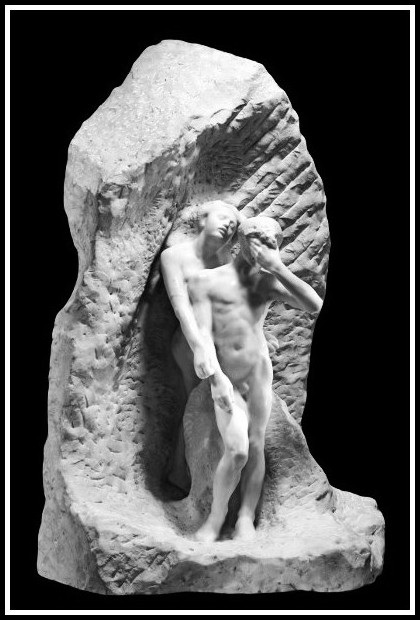

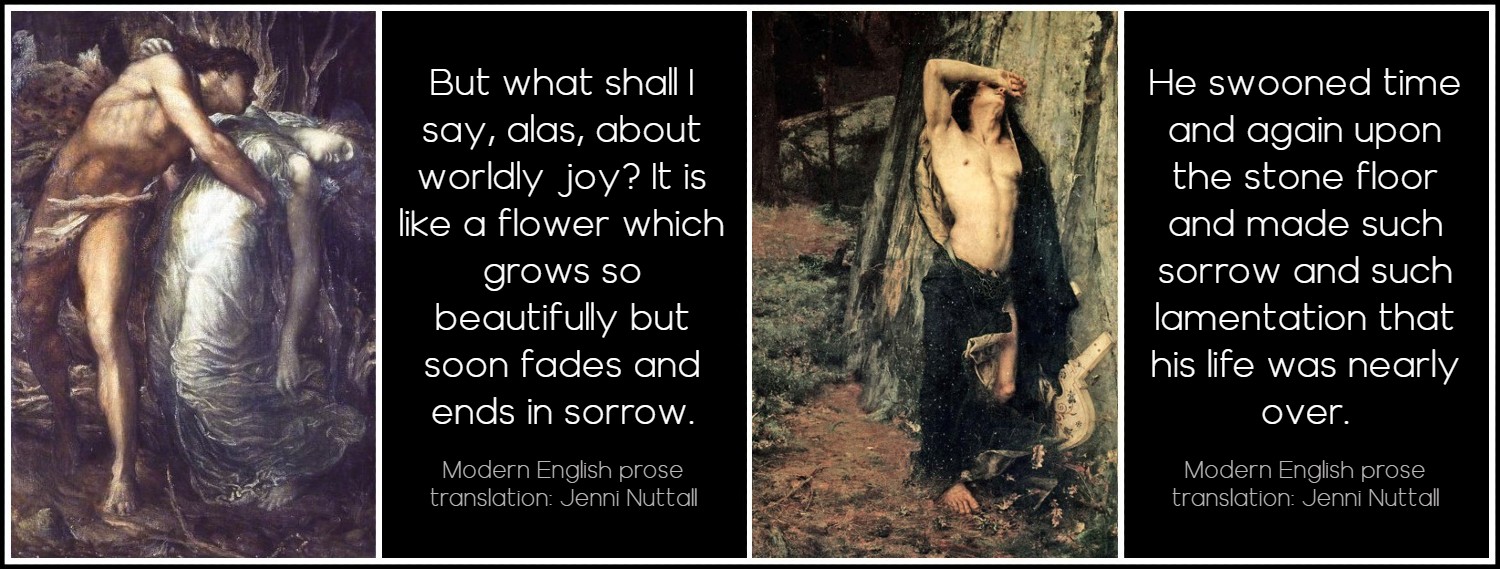

Rodin, Orpheus & Eurydice, 1887

For the Greeks, Orpheus dates from one generation before the Trojan War. He was the son of a Muse, presumably Calliope; according to some, his father was Apollo, but to most it was the Thracian river god Oiagros. Orpheus could sing and play the lyre so sweetly that he could tame violent beasts and attract all of nature. He possessed the secrets of the underworld, where he went in quest of his wife, Eurydice, who had died prematurely of a snakebite. Although he succeeded with his song in persuading the infernal gods to allow him to lead his wife up to the open air, he failed to follow the divine injunction (the law of Persephone) against looking back at her. After the second loss of his wife, he shunned women and even became the originator of homosexual love, at least among the Thracians. The most established tradition makes him the fatal victim of the Thracian women, who in a Bacchic frenzy murdered him either for rejecting them or for enticing away their husbands; alternatively, Dionysos may have sent his savage maenads to punish Orpheus for worshipping Apollo. According to the most widely accepted version of the sacrificial murder, the body of Orpheus was completely dismembered, and his head and lyre were thrown into the river Hebros; his head miraculously continued to sing and the lyre to play as they floated to Lesbos. There the head was buried in the shrine of Dionysos, and the lyre was enshrined in the temple of Apollo. The head achieved renown as a giver of oracles until a jealous Apollo suppressed it.

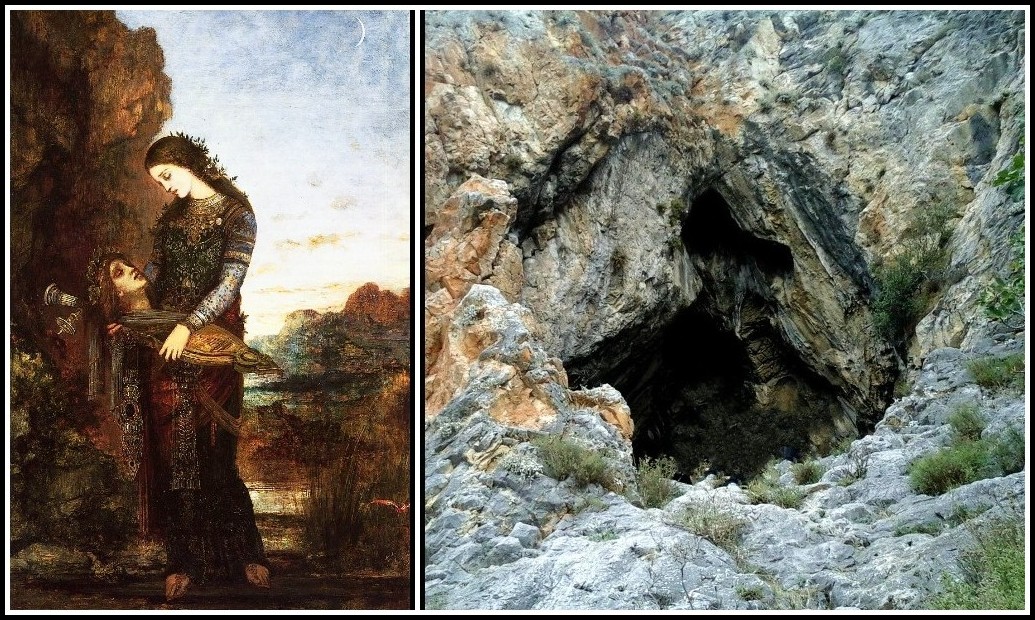

Gustave Moreau, Young Thracian Woman Carrying the Head of Orpheus, 1875 | Stratisav, The Oracle of Orpheus, Lesbos

According to another early Greek version of the myth, Orpheus was victorious in retrieving his wife from the underworld; this successful resolution was later perpetuated in medieval interpretations of the myth. Since the Renaissance, however, the Roman version of the myth has tended to dominate literary and artistic images of it. The Romans combined what had been two separate Greek legends—one of Orpheus’s magical powers as a musician, the other of his descent into the underworld to fetch his wife. They also enriched the myth with the new theme of romantic love: Virgil introduced ‘the unhappy ending’ (Georgics 4.453-527) and Ovid further sentimentalized the story (Metamorphoses 10.1-85, 11.1-66).

Virgil | Guido Reni, Orpheus & Eurydice, 1597 | Ovid

Because of the association between Greek music and poetry (invariably sung), the ancient Greeks thought of Orpheus as a poet as well as a musician and a singer, and even as the inventor of writing and all the arts. He was a theologos, who sang of the gods and the origins of all things. The magical and mystical powers of his music caused people to regard him as the founder of all the mysteries and as the introducer of religious rites and writings into Greece.

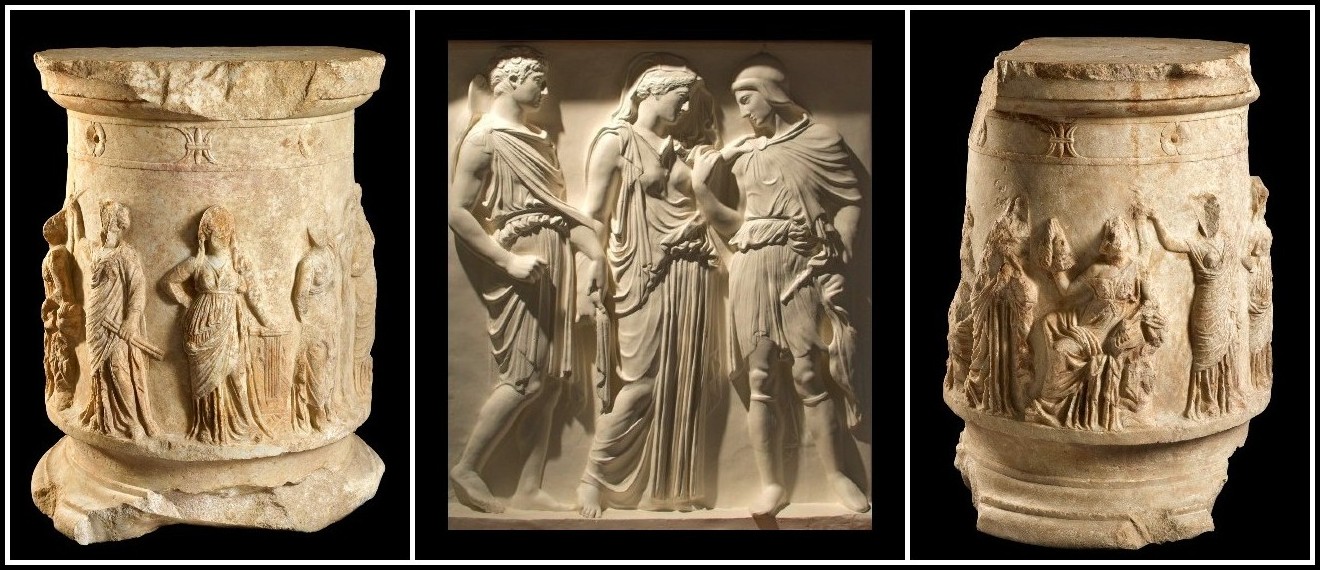

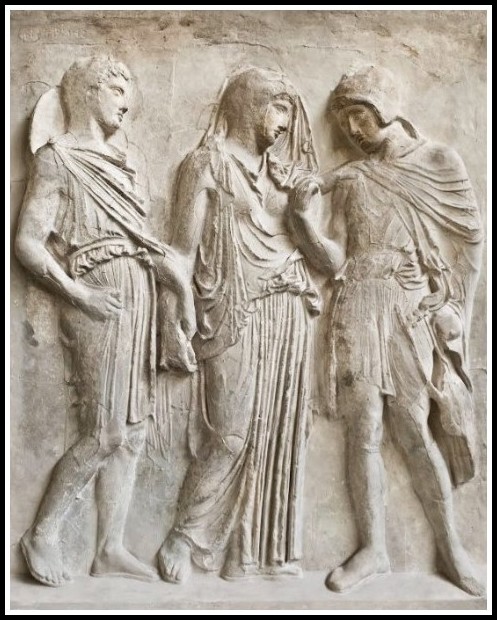

The nine Muses: relief on a marble altar, 100 BC (BritMus) | Hermes, Eurydice, Orpheus: copy of original from 100 BC-100 CE (Wilcox Classical Museum)

Central to Orphic myth is the story of the slaying of Dionysos, the young child of Zeus and Persephone, by the Titans. These not only tore to pieces, but also boiled, roasted, and then ate him. From the soot of the Titans, who were burned in retribution by Zeus’s thunderbolt, man emerged, and from the collected remains of the child, Dionysos rose again. Only lifelong purity could eradicate man’s guilt for the crime of his Titan ancestors. Abstinence from everything in which there was soul and sexual abstinence were demanded of the Orphics. Orpheus evidently preached a strict way of life regulated by prohibitions through which purification could be achieved. Plato (Cratylus 400c) attributed to Orpheus and his followers a doctrine that explains their renunciations: the soul must ‘suffer punishment’ and be enclosed in the body, which both imprisons and protects the soul until it ‘has paid what is due.’

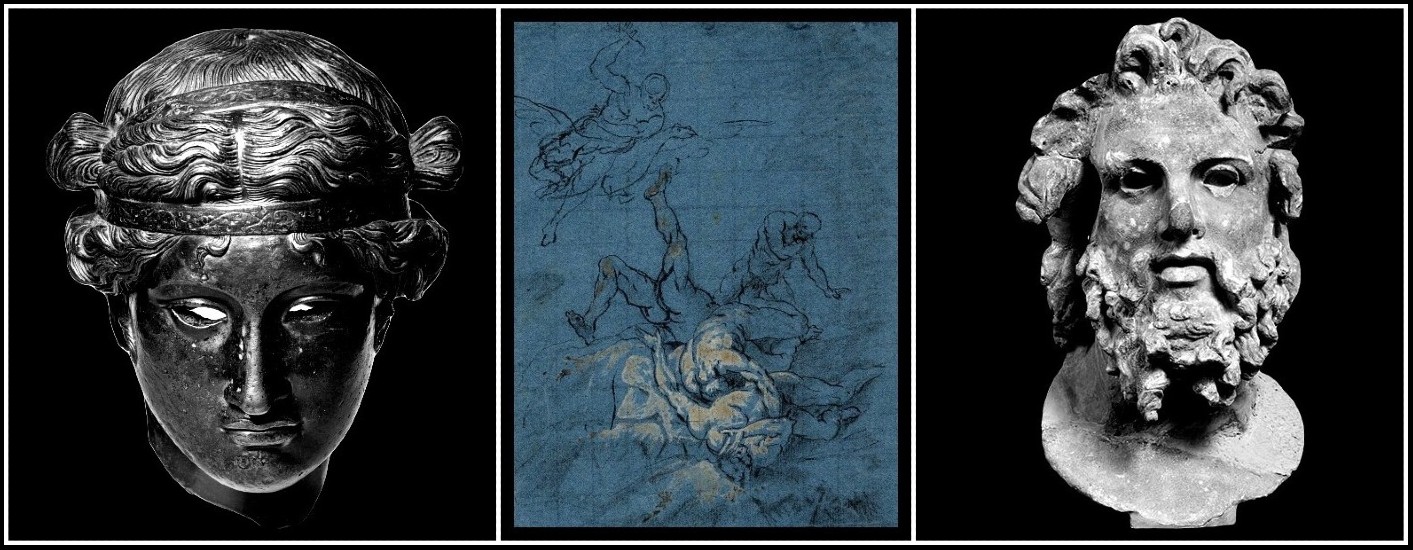

Bronze head of Dionysus, 30 BC (BritMus) | Januarius Zick, Fall of the Titans, 1756 (BritMus) | Marble head of the Titan Anytos, 185 BC (NAM Athens)

Controversies about Orphism concern the extent to which it was a unified spiritual cult or sect based on the Dionysos myth and the doctrines of immortality and transmigration of the soul later developed by Plato. The doctrine of transmigration of souls appeared in Greece toward the end of the sixth century BC and was associated with both Orpheus and Pythagoras. This tenet assumes that a soul exists in every man and animal and preserves its own identity independently of the body that passes away. Herodotus states that the soul must wander through the cosmos and be drawn in with the breath of a newly born creature; Plato tells us that the doctrine of transmigration was presented in the mysteries, where it had strong believers. Aristotle relates that ‘in the so-called Orphic poems’ a soul, borne upon the winds from out of the universe (‘the whole’), enters a living creature with its first breath; he also clearly knew Pythagorean myths indicating that ‘any soul can enter any body.’ A satirical poem by Xenophanes attributes to Pythagoras the belief that a human soul can exist in a dog.

Greek philosophers (detail): BritMus | Dog: Charles Deluvio | Xenophanes: A. M. Miller, Greek Lyric (Hackett Publishing, 1996) p. 109

Although their explanations of the world differ, many Orphic and Pythagorean ideas and practices are too close to be disentangled. Orphic and Pythagorean doctrines of metempsychosis coincided, as did their emphases on abstinence and purification. A moral dualism underlies both Pythagoreanism and Orphism: the good part of the world is represented by such principles as form, limit, light, and the universe, which reveals the harmony and order that when contemplated become implanted in the human soul. Pre-Platonic legends even have Pythagoras prove his doctrine of immortality by a descent into the underworld; Pythagoras regarded Orpheus as his chief patron, because experiments in music underlay Pythagoras’s understanding of numerical ratios and he presumably had learned his number theology from Orpheus. Music’s position of primacy in Pythagoreanism is clear in the conception of the universe as a harmonia.

Salvator Rosa, Pythagoras Emerging from the Underworld, 1662 | Corot, Orpheus Leading Eurydice from the Underworld, 1861

Most Pythagoreans adhered to a vegetarian diet as a form of renunciation of the cannibalism of the city-state. Renunciation of the world by the Orphics in their diet, another rejection of the city-state’s values and practices, was based on one of Orpheus’s most important teachings: ‘to abstain from murders’, that is, to reject the tradition of blood sacrifice and a meat diet. Like the Pythagoreans, the Orphics viewed as cannibals those who consumed meat and did not practice the Orphic life, neglecting to purify the divine element imprisoned in man by the Titans and to bridge the gap between man and the gods opened up by the bloody sacrifice of Dionysos.

Consulting the Oracular Head of Orpheus, Attic red-figured hydria, 450 CE (detail) | Dionysus, Rome, 150 CE (detail)

Because of his civilized character, his soothing music on the lyre and his homosexuality, many have emphasized the closeness of Orpheus to Apollo. The Orphic concept of music was based on the instrument of Apollo, as well as on the voice and a concern with enchantment and calm. Considering the Orphic interest in the purification of the soul and its reliance on asceticism, the natural concomitant in music was a harmonic science, more soothing than rapturous Dionysiac music and dance.

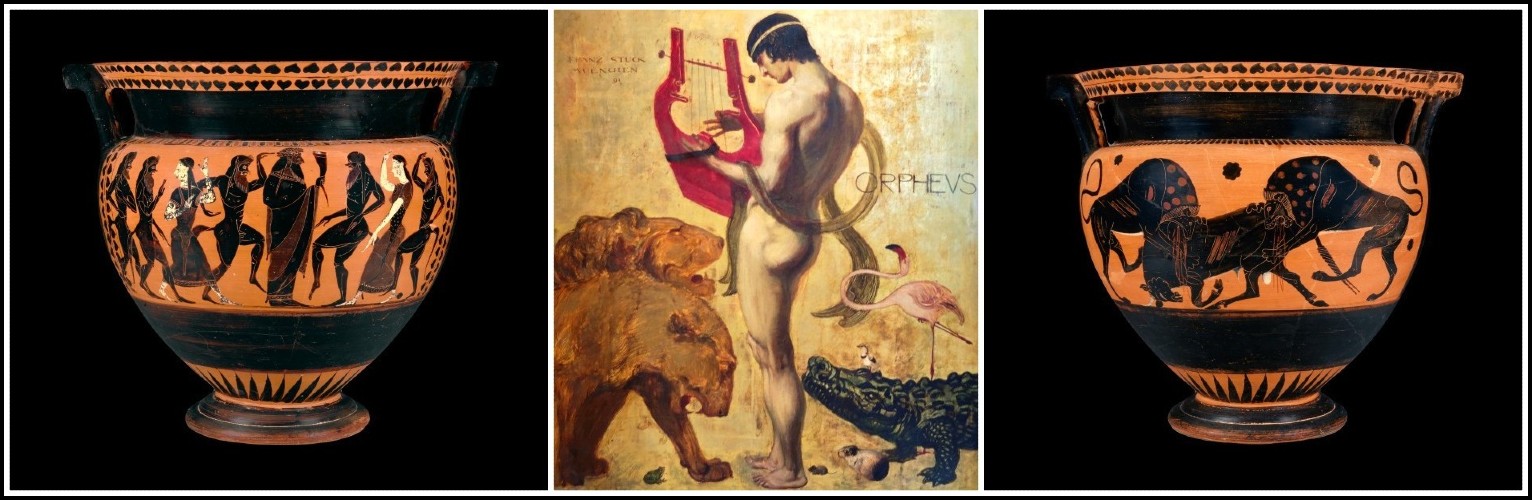

‘Rapturous Dionysiac music & dance’: Attic black-figure krater, 520 BC | ‘Soothing harmonic science’: Franz von Stuck, Orpheus, 1891

The prominence of the Dionysos myth in Orpheus’s teachings, however, his own descent into the underworld and return from it, and his death by dismemberment have linked Orpheus with Dionysos. The name Orpheus, which means ‘obscure’ in Greek, is related to the ‘nocturnal’ Dionysos, and is appropriate for a hero known for his journey into the underworld. Nevertheless, Orpheus was murdered by followers of Dionysos, and his oracle was suppressed by Apollo. He therefore remains an ambiguous figure, similar to both gods but separate from them. He has been considered variously a Bronze-Age Mycenaean shaman, a Thracian priest of Apollo who founded a Bacchic religion reformed with certain Apolline features, and a fictional figure.

Pierre-Amédée Marcel-Beronneau (1869-1937), Orpheus & Eurydice

The Greek religion makes a basic contrast between the Olympian religion of the heavens, represented by Apollo, and the chthonic religion of the earth, represented by Dionysos. The interest of the Orphics in Apollo and Dionysos was dramatized by Aeschylus in a lost play, the Bassarae, in which Orpheus is portrayed as a devotee of the sun (Apollo), angering Dionysos, who sends his maenads to murder Orpheus.

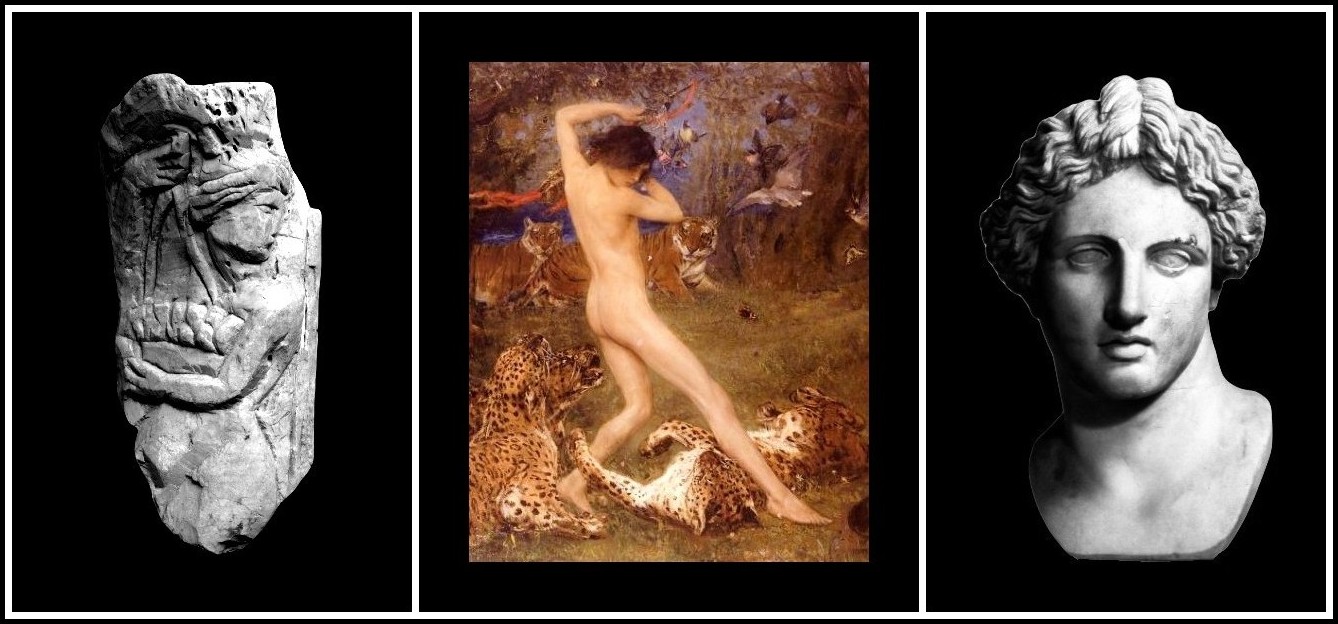

Plaque with Maenad, 400-640 CE (Met) | John Macallan Swan, Orpheus, 1896 (detail) | Head of Apollo, 100 CE (BritMus)

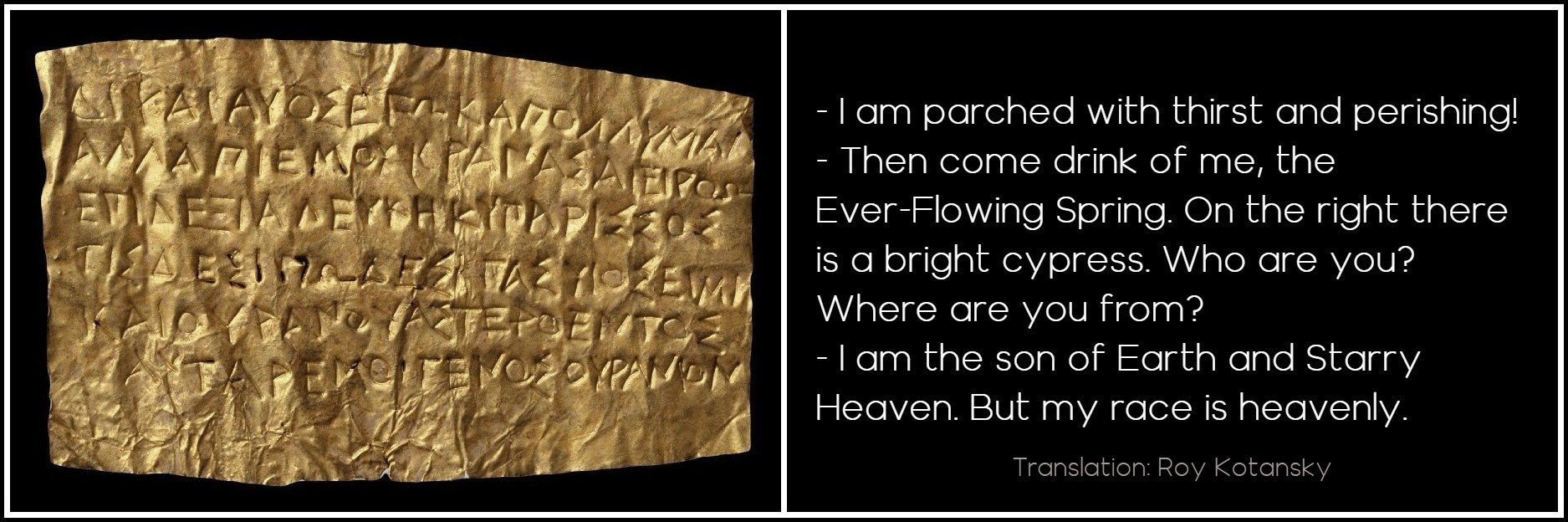

Like Orpheus’s relationship with Dionysos, the interrelationship of the Bacchic mysteries and the Orphic movement is much debated. Starting in the time of Herodotus, the Orphic religion was identified with the Dionysiac. In the Phaedrus, Plato has Dionysos preside over mysteries that effect liberation from ancient guilt and better hopes for the next world and are performed according to the poems of Orpheus. Euripides mentions people who are vegetarians, celebrate Bacchic rites, and consider Orpheus their master. The Orphic hymns are now regarded as part of the Dionysiac mysteries; the Hipponion lamella identifies the famous gold plates generally called Orphic as Bacchic; Orphic and Bacchic are alike in their concern for burial and the afterlife and the myth of Dionysos Zagreus. Dionysiac omophagy may be seen as the homologue of Orphic vegetarianism in that both rejected the system of values wedded to blood sacrifice. Yet as a savage god who ate human flesh and, consequently, identifiable with bloodshed, Dionysos is markedly opposed to the pure Orphic life. Dionysos is a complex figure, a magician capable of taking diverse forms, and when reborn was considered to have inaugurated the reign of refound unity. Orphism makes a strong distinction between the golden age Dionysos, sovereign of refound unity, and the bestial deity of omophagy.

Lamella Orphica, 350 BC (Getty Museum)

Vestiges of the late antique conception of Orphism remain in much later thought, especially the insistence on the unity and singleness of the cosmos, which the ancients considered to be an Orphic concept. Evidently, in Orphic thought, men appeared in an originally perfect world, but then were condemned to individual existence. The dismemberment of Dionysos became part of Platonic metaphysics with Plato’s Timaeus, according to which the world soul results from mixing an undivided and a divided principle with intermediate being. Among later Neoplatonists, Dionysos represents the divine principle divided up into the real bodies in this world to be reassembled and restored to the primordial unity.

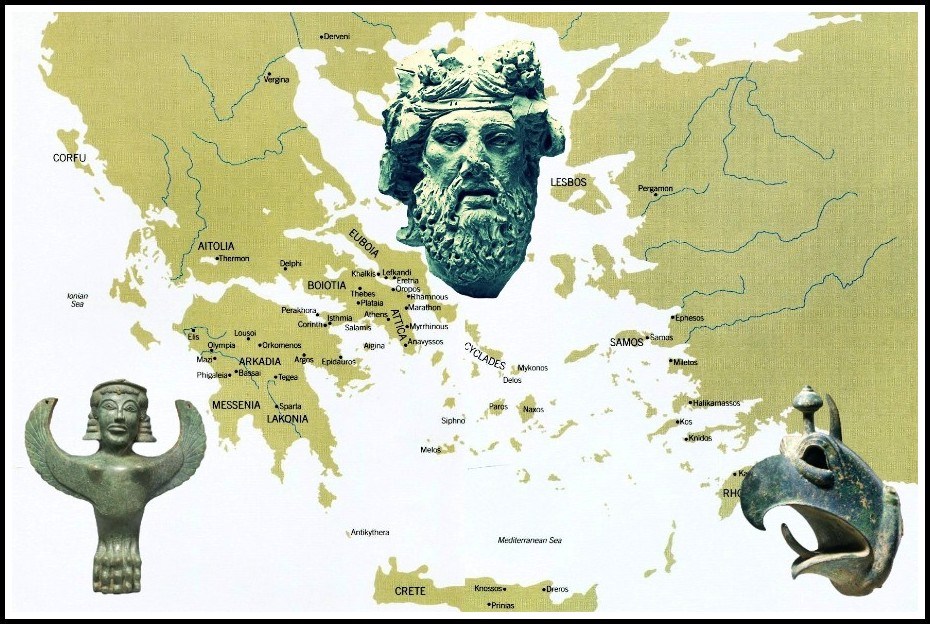

MAINLAND GREECE & AEGEAN: ARCHAIC & CLASSICAL SITES

Bronze foot-sphinx, 600 BC | Head of Dionysos, 50 BC | Bronze head-griffin, 650 BC | Composite: RJ

According to a story dating from the third century BC, Orpheus was a monotheist and, hence, could be used by Hellenistic Jews and early Christians to advance their respective causes. The Testament of Orpheus, an Alexandrian poem, was attributed to Orpheus, who was regarded as the son of Moses and as a theologian. Of the Christian apologists, Clement of Alexandria was the most intrigued with Orpheus. Orpheus served as the model for the Good Shepherd in late antique art and soon was identified with Christ on a more profound level. Medieval allegorists, following the lead of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, revived an interest in Eurydice by including her in their commentaries as reason, the complement to passion (Orpheus) in man’s soul. By the late Middle Ages, the myth had evolved into a courtly romance extant in two versions, Sir Orfeo and Robert Henryson’s narrative poem Orpheus and Eurydice.

G. F. Watts, Orpheus & Eurydice, 1869 | Sir Orfeo | Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, The Lament of Orpheus, 1876 | Orpheus & Eurydice, Henryson

Marsilio Ficino provides the key to an understanding of the early Renaissance conception of Orpheus. In 1462 he translated the so-called Orphic hymns from Greek into Latin. Ficino based his Neoplatonic theology and musical cosmology on the persona of Orpheus, who represented to him man striving to comprehend the order of the universe; Orpheus was an extraordinary poet possessing all four furores—poetic, religious, prophetic, and amorous. Because Platonic love manifested unity with God, Ficino downplayed Orpheus’s amorous failure. Angelo Poliziano’s Orfeo (1480), a pastoral devoid of polemical or allegorical content, was unusual in its time but influential later in the sixteenth century. Orpheus makes his last appearance as a Platonic ideal in Francesco Patrizi’s treatise Della Poetica, which refuted Aristotle’s mimetic theory and viewed the singer as possessed with divine inspiration and symbolic of the unity of art and religion. By the late sixteenth century, when the concept of tragedy had been explored and love was detached from Platonic idealism, Orpheus was regarded as both a great artist and a tragic figure, and his experience with Eurydice had acquired positive connotations.

Alexandre Séon, Orpheus Laments, 1896 (detail) | Michel Richard-Putz (1866-1934), Orpheus & Eurydice | Rodin, Orpheus, 1908

From his role in the Renaissance as civilizer and symbol of the bonds linking man’s achievements and institutions and man with nature, Orpheus evolved into an emblem of harmonious order in the universe—as well as of the ‘impatience of philosophy’—for seventeenth-century rationalists such as Francis Bacon. From the eighteenth through the early twentieth century, Orpheus maintained a prominent position in esoteric writings. The Romantic quest for reunification of the cosmos was evident in the strong attraction of several writers to a magical Orpheus with marked gnostic flavor; to the literary symbolists and their twentieth-century descendants (most notably Rainer Maria Rilke), Orpheus represented both the suffering artist and the poet able to rediscover unity through a dialectical scheme in which opposites coincide.

Pierre Marcel-Beronneau, Orpheus in Hades, 1897 | Rilke, ‘Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes’ | Gustave Moreau, Orpheus at the Tomb of Eurydice, 1891

The traditional blend of Apollonian and Dionysian elements in the character of Orpheus continues in representations of him by twentieth-century artists, who may suggest his resemblance to one god or the other or a fusion of them. Several artists reflect the impact of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy, stating a dichotomy between Apollonian harmony and restraint and Dionysian drunken frenzy and arguing that a fusion of the Apollonian and Dionysian characterized the best Greek tragedy. The ancient Greek contrast between Olympian and chthonian is extended by Nietzsche and appears in the light and dark symbolism that characterizes many twentieth-century representations of Orpheus, evoking Apollonian and Dionysian associations, respectively. Nietzsche later defined ‘the mystery doctrine of tragedy’ as ‘the fundamental knowledge of the oneness of everything existent, the conception of individuation as the primal cause of evil, and of art as the joyous hope that the spell of individuation may be broken in augury of a restored oneness’. The basis of this doctrine is ‘the problem of the one and the many,’ of great concern to the Greeks of the sixth century BC, as demonstrated by the Orphic myth of the dismemberment and rebirth of Dionysos.

Jean Delville, The Death of Orpheus, 1893

JUDITH ELEANOR BERNSTOCK

Under the Spell of Orpheus: The Persistence of Myth in Twentieth-Century Art

Click or tap the image to go to a description of the book

JUDITH ELEANOR BERNSTOCK

Under the Spell of Orpheus

PART II

ORPHEUS & EURYDICE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Richard Jonathan

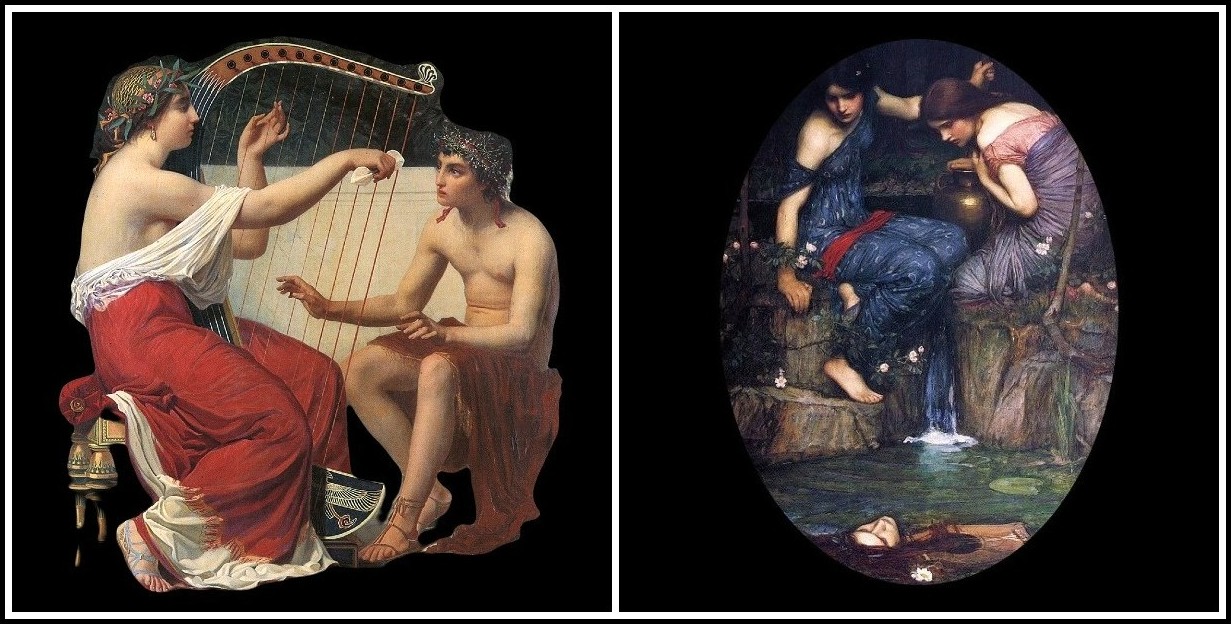

Auguste Hirsch, Calliope Teaching Music to the Young Orpheus, 1863 | John William Waterhouse, Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus, 1900

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 14

̶ Are you afraid to look back, Sprague? Do you think you’re going to lose your Eurydice like Orpheus did?

There’s a steely edge to the blue of her eyes, echoed by the blue of the jacket and pants she’s wearing. White T-shirt and tennis shoes: Cool.

̶ To tell the truth, I’ve never understood that mysterious moment when Orpheus looks back. All that effort to reach Eurydice in the Underworld, and then—just before reaching the light—he looks back and loses her. I confess, I just don’t get it.

̶ It’s about faith, Simona says.

̶ Faith?

̶ Yeah. Rumour has it that love can’t survive without it.

The scalloped hem of her voile skirt falls to just above her knees: I won’t fall that far. She continues:

̶ He didn’t have the faith to believe she’d still be there. He didn’t love her enough.

She loves me, she loves me not: White daisies pattern the navy skirt, white as the white of her sweater.

Odilon Redon (1840-1916), Head of Orpheus I

Riva comes in:

̶ Then again, it could be the opposite. Maybe he loved her too much. Maybe it was excess of love that made him look back.

Beneath her plush burgundy blazer, the black of her silk-chiffon top is transparent. As transparent as she is?

̶ Either way, she continues, we all know what happened to him!

̶ Remind me, I say. I’ve forgotten.

I like her red lips and long hair. I like the light in her eyes.

̶ A lost soul, Sprague. That’s what he became. Ended up getting ripped apart by the Maenads.

̶ Who were jealous of his love, Héloïse specifies.

̶ Legend has it only his head survived, Nicole adds. Fell into a river, drifted down to the sea.

Odilon Redon (1840-1916), Head of Orpheus II

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

PART III

ORPHEUS & EURYDICE

KAJA SILVERMAN ON ORPHEUS & EURYDICE IN RAINER MARIA RILKE

Posted by kind permission of Kaja Silverman, Professor Emerita of Art History, University of Pennsylvania

From Kaja Silverman, Flesh of My Flesh (Stanford University Press, 2009) pp. 68-70.

The complete text of ‘Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes’, presented here before the excerpt from Kaja Silverman’s essay,

is from Galway Kinnell & Hannah Liebmann (translators), The Essential Rilke (The Ecco Press, 2000) pp. 18-25.

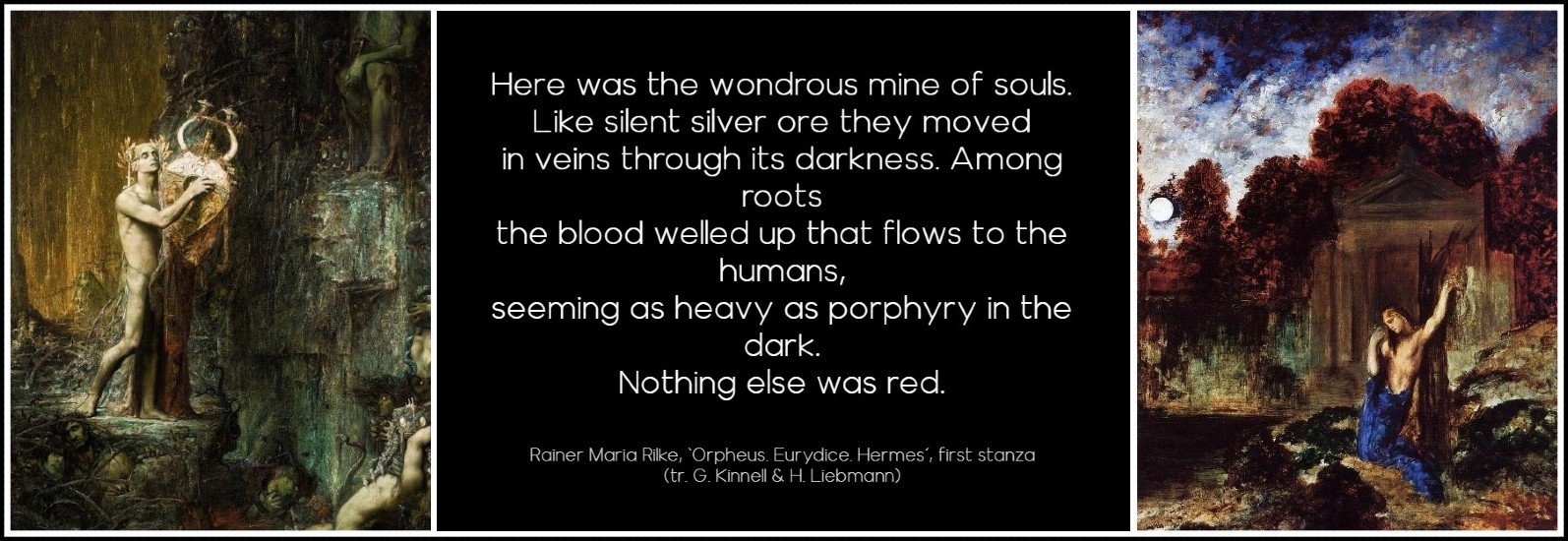

Plaster copy, Hermes, Eurydice & Orpheus, ancient Greek original

ORPHEUS. EURYDIKE. HERMES

Rainer Maria Rilke

Das war der Seelen wunderliches Bergwerk.

Wie stille Silbererze gingen sie

als Adern durch sein Dunkel. Zwischen Wurzeln

entsprang das Blut, das fortgeht zu den Menschen,

und schwer wie Porphyr sah es aus im Dunkel.

Sonst war nichts Rotes.

Felsen waren da

und wesenlose Wälder. Brücken über Leeres

und jener große graue blinde Teich,

der über seinem fernen Grunde hing

wie Regenhimmel über einer Landschaft.

Und zwischen Wiesen, sanft und voller Langmut,

erschien des einen Weges blasser Streifen,

wie eine lange Bleiche hingelegt.

Und dieses einen Weges kamen sie.

ORPHEUS. EURYDICE. HERMES

Rilke | G. Kinnell & H. Liebmann

Here was the wondrous mine of souls.

Like silent silver ore they moved

in veins through its darkness. Among roots

the blood welled up that flows to the humans,

seeming as heavy as porphyry in the dark.

Nothing else was red.

There were rocks

and spectral forests. Bridges across emptiness

and that broad gray blind pond

suspended above its distant bottom

like a rainy sky above a landscape.

And between gentle, forbearing meadows,

appeared the pale strip of the single path,

laid out like a long bleaching place.

And up this one path they came.

John Ruskin, Moss and Wild Strawberry, 1873

Voran der schlanke Mann im blauen Mantel,

der stumm und ungeduldig vor sich aussah.

Ohne zu kauen fraß sein Schritt den Weg

in großen Bissen; seine Hände hingen

schwer und verschlossen aus dem Fall der Falten

und wussten nicht mehr von der leichten Leier,

die in die Linke eingewachsen war

wie Rosenranken in den Ast des Ölbaums.

Und seine Sinne waren wie entzweit:

indes der Blick ihm wie ein Hund vorauslief,

umkehrte, kam und immer wieder weit

und wartend an der nächsten Wendung stand, –

blieb sein Gehör wie ein Geruch zurück.

Manchmal erschien es ihm als reichte es

bis an das Gehen jener beiden andern,

die folgen sollten diesen ganzen Aufstieg.

Dann wieder wars nur seines Steigens Nachklang

und seines Mantels Wind was hinter ihm war.

Er aber sagte sich, sie kämen doch;

sagte es laut und hörte sich verhallen.

Sie kämen doch, nur wärens zwei

die furchtbar leise gingen. Dürfte er

sich einmal wenden (wäre das Zurückschaun

nicht die Zersetzung dieses ganzen Werkes,

das erst vollbracht wird), müsste er sie sehen,

die beiden Leisen, die ihm schweigend nachgehn:

In front, the slender man in the blue cloak,

who gazed out ahead, silent, impatient.

His steps devoured the path in giant bites,

not bothering to chew, from the folds of his cloak,

his hands hung down heavy and locked shut,

oblivious to the now weightless lyre

which had grown into his left arm

as tendrils of a rosebush into an olive bough.

His senses were as if split in two:

while his gaze, like a dog, ran out ahead,

turned, came back, and again and again, far

and waiting, stood at the next bend,—

his hearing lagged behind like a smell.

At times it seemed to him to reach

back to the sounds of walking of the two others

supposed to be following him this whole ascent.

And then again, it was only his own steps’ echoes

and the wind stirring his cloak that were behind him.

But he told himself they were still coming;

said it aloud and heard his tones die away.

They were still coming, it was just that they

walked so terribly quietly. If only he

could turn around just once (if looking back

wouldn’t subvert the whole undertaking,

not yet completed), he would have to see them,

those two soft walkers following without a word:

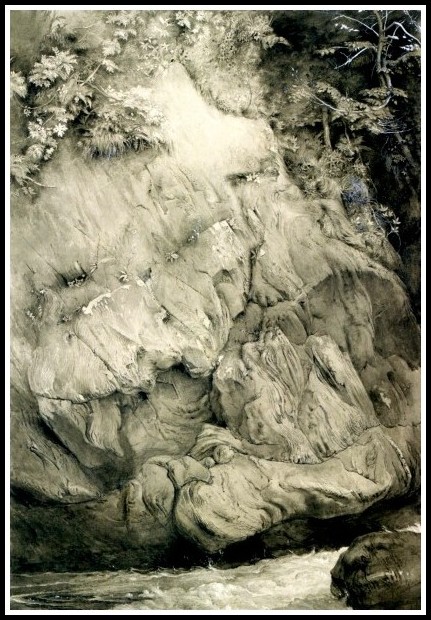

John Ruskin, Study of Gneiss Rock (Glenfinlas), 1853

Den Gott des Ganges und der weiten Botschaft,

die Reisehaube über hellen Augen,

den schlanken Stab hertragend vor dem Leibe

und flügelschlagend an den Fußgelenken;

und seiner linken Hand gegeben: sie.

Die So-geliebte, dass aus einer Leier

mehr Klage kam als je aus Klagefrauen;

dass eine Welt aus Klage ward, in der

alles noch einmal da war: Wald und Tal

und Weg und Ortschaft, Feld und Fluss und Tier;

und dass um diese Klage-Welt, ganz so

wie um die andre Erde, eine Sonne

und ein gestirnter stiller Himmel ging,

ein Klage-Himmel mit entstellten Sternen – :

Diese So-geliebte.

Sie aber ging an jenes Gottes Hand,

den Schrittbeschränkt von langen Leichenbändern,

unsicher, sanft und ohne Ungeduld.

Sie war in sich, wie Eine hoher Hoffnung,

und dachte nicht des Mannes, der voranging,

und nicht des Weges, der ins Leben aufstieg.

Sie war in sich. Und ihr Gestorbensein

erfüllte sie wie Fülle.

Wie eine Frucht von Süßigkeit und Dunkel,

so war sie voll von ihrem großen Tode,

der also neu war, dass sie nichts begriff.

The god of the way and of tidings from afar,

a wide brim above his bright eyes,

his slender wand held out in front,

beating wings at his ankles;

and, entrusted to his left hand: she.

The one so loved that a single lyre

raised more lament than lamenting women ever did;

and that from the lament a world arose in which

everything was there again: woods and valley

and path and village, field and river and animal;

and around this lament-world, just as

around the other earth, a sun

and a starry silent heaven turned,

a lament-heaven of disordered stars—:

This one so loved.

But now she walked at this god’s hand,

her steps impeded by long winding-sheets,

unsure, slowly, without impatience.

She was within herself, great with expectation,

and gave no thought to the man going on ahead

or to the path leading up to life.

She was within herself. And her being dead

filled her like great plenitude.

Like a fruit, with its sweetness and darkness,

was she full with her great death,

so new to her she understood nothing.

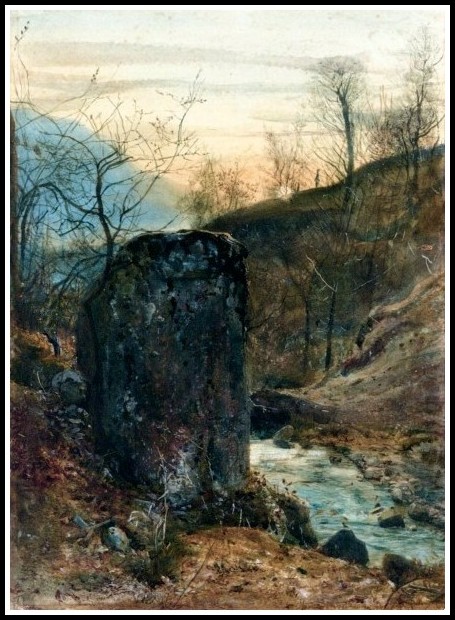

John William Inchbold, Stream with Standing Stone, 1870

Sie war in einem neuen Mädchentum

und unberührbar; ihr Geschlecht war zu

wie eine junge Blume gegen Abend,

und ihre Hände waren der Vermählung

so sehr entwöhnt, dass selbst des leichten Gottes

unendlich leise, leitende Berührung

sie kränkte wie zu sehr Vertraulichkeit.

Sie war schon nicht mehr diese blonde Frau,

die in des Dichters Liedern manchmal anklang,

nicht mehr des breiten Bettes Duft und Eiland

und jenes Mannes Eigentum nicht mehr.

Sie war schon aufgelöst wie langes Haar

und hingegeben wie gefallner Regen

und ausgeteilt wie hundertfacher Vorrat.

Sie war schon Wurzel.

Und als plötzlich jäh

der Gott sie anhielt und mit Schmerz im Ausruf

die Worte sprach: Er hat sich umgewendet -,

begriff sie nichts und sagte leise: Wer?

Fern aber, dunkel vor dem klaren Ausgang,

stand irgend jemand, dessen Angesicht

nicht zu erkennen war. Er stand und sah,

wie auf dem Streifen eines Wiesenpfades

mit trauervollem Blick der Gott der Botschaft

sich schweigend wandte, der Gestalt zu folgen,

die schon zurückging dieses selben Weges,

den Schritt beschränkt von langen Leichenbändern,

unsicher, sanft und ohne Ungeduld.

She had come into another virginity

and wasn’t to be touched; her sex was closed

like a young flower toward evening,

and her hands were by now so unused

to being wed that even the gentle god’s

infinitely soft, light, guiding touch

offended her as too intimate.

She was no more the woman of flaxen hair

who sometimes resonated in the poet’s songs,

no more the odor and island of the wide bed,

and that man’s possession no more.

She was already loosened like long hair

and surrendered like fallen rain

and meted out like a hundred-fold supply.

Already she was root.

And when suddenly, abruptly,

the god stopped her and in a pained voice

said: ‘He’s turned around’,

she did not understand and quietly answered: ‘Who?’

In the distance, dark before the bright exit,

stood someone whose face

could not be recognized. He stood and saw

how on a strip of the meadow path

with mournful look the god of tidings

silently turned to follow the figure

who already had started back down,

her steps impeded by long winding-sheets,

unsure, slowly, without impatience.

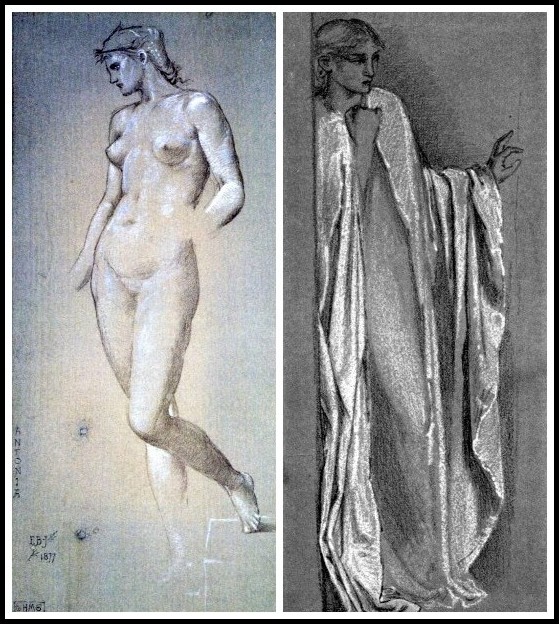

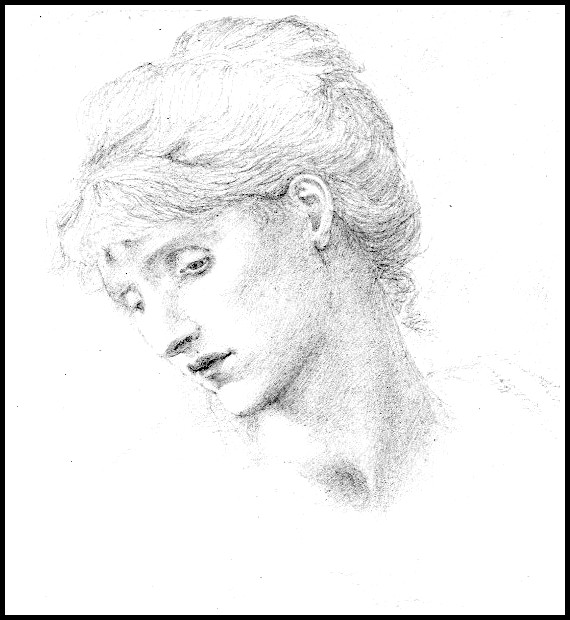

Edward Burne-Jones: Study for ‘Danaë’, 1885 | Antonia, 1877

Rilke’s work is full of figures who have been struck down prematurely, and almost all of them are also female. So was their biographical prototype. The poet had a baby sister who died before he was born, and his grief-stricken mother tried to resurrect her through him by naming him René Maria and dressing him like a girl. This rendered Rilke exquisitely sensitive to all things feminine, but since his sister could live again only if he took her place in the coffin, it also instilled in him a paralyzing fear of death. When he was a child, he suffered from a recurrent nightmare whose central image continued to haunt him: he dreamt that ‘he lay near an open grave, before a tall gravestone that threatened to topple into the grave at the slightest movement… [He saw his name] engraved on the precipitous stone, so that it could he mistaken for him, if it disappeared forever into the grave beneath him.’ There was only one way to remove his name from the gravestone, and that was to replace it with his sister’s.

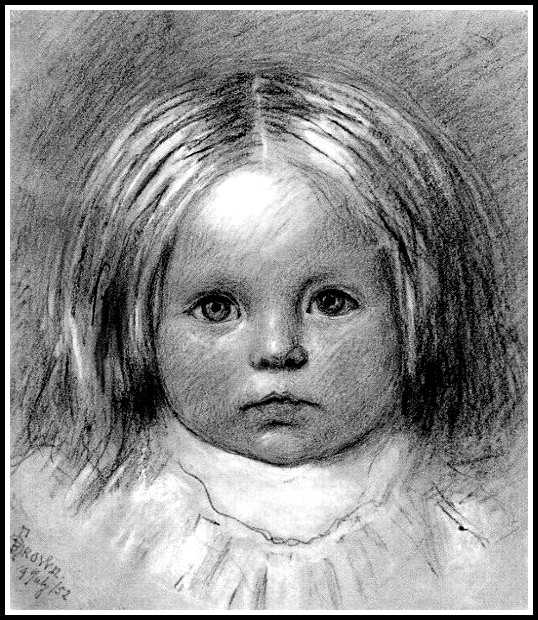

Ford Madox Brown, Catherine Madox Brown, 1852

Consequently, although most of Rilke’s close friendships were with women, he was emphatically masculine when it came to mortality; death was something that happened on the other side of the gender divide. He found support for this claim in a time-honored place: the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Rilke organized two early poems around this myth: ‘Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes’ (1904) and Requiem for a Friend (1908). He also came back to it later, through the Sonnets to Orpheus (1922) and a poem initially intended for the Duino Elegies. Rilke gravitated to this story because Eurydice dies and returns to life but then leaves again, just as he wanted his sister to do. But Eurydice stands for a number of other women as well, and each time the poet restaged the story, he altered it in important ways.

Edward Burne-Jones, Violet Manners, later Duchess of Rutland, 1883

In ‘Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes’, Rilke adds the ‘god of speed and distant messages’ to the cast of characters, but reduces the story to the movement of these three figures through a mysterious cavern. He also isolates each of them from the others. Eurydice walks beside Hermes, and behind Orpheus. but she doesn’t notice either of them; Orpheus is uncertain whether he is hearing her footsteps or his own; and Hermes is unable to bridge the distance between the two of them. Orpheus has also forgotten that he is a musician: ‘his hands hang at his sides, / tight and heavy, out of the falling folds, / no longer conscious of the delicate lyre / which has grown into his left arm.’

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Portrait of Fanny Cornforth, 1860

The fifth stanza ends with the word ‘she’, and this pronoun ushers in an extended celebration of Eurydice, first as ‘a woman so loved that from one lyre there came / more lament than from all lamenting women’, and then as someone who is no longer ‘that man’s property’. Since most of the rest of the poem is also localized through her, Orpheus drops out of the picture until the very end, when Hermes draws him to her attention, and even then he remains a small figure on the horizon. ‘And when, abruptly, / the god put out his hand to stop her’. Rilke writes, ‘saying / with sorrow in his voice: He has turned around—, / she could not understand, and softly answered / ‘Who?’ / Far away, / dark before the shining exit-gates, / someone or other stood, whose features were unrecognizable’.

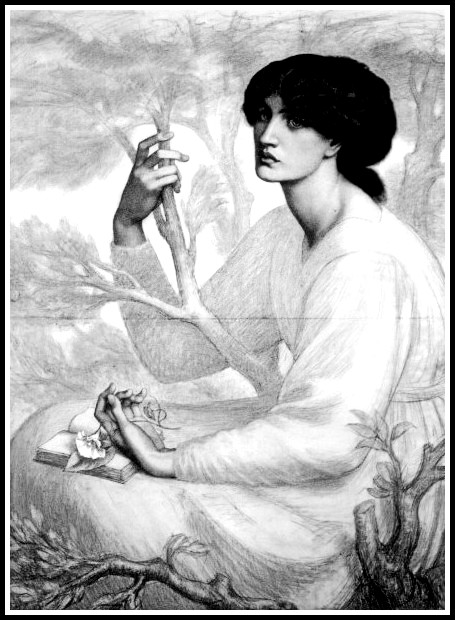

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Day Dream, 1872-78

Since ‘Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes’ reorganizes the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice around Eurydice, liberates her from the category of a possession, and transforms the forlorn but acquiescent ‘farewell’ she utters in The Metamorphoses into an annihilating ‘who?’ it feels like a feminist poem. Rilke clearly meant it to be read that way, because in a letter from the same year he presents his ideas about heterosexuality as a kind of feminist manifesto. ‘We are only just now beginning to consider the relation of one individual to a second individual objectively and without prejudice, and our attempts to live such relationships have no model before them,’ he wrote to Franz Xaver Kappus. ‘This humanity of woman will come to light when she has stripped off the conventions of mere femaleness in the transformations of her outward status.’ When this transformation is complete, man and woman will be ‘two solitudes’, who ‘protect and border and greet each other’.

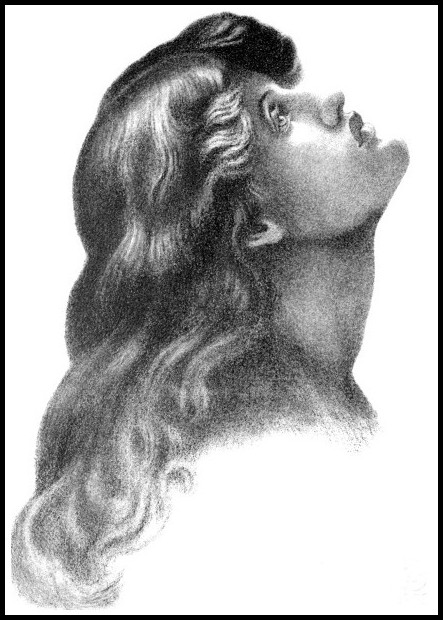

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Head of a Woman, 1875

But Rilke’s 1904 version of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth builds to the usual climax: Orpheus turns around to look at Eurydice, and she sinks back to Hades. He also makes no attempt to restore her to the world, or even establish contact with her, and it is not hard to see why: her presence disables his music. Finally, Eurydice escapes ‘patriarchy’ not through work or a more satisfying kind of relationship, but rather by dying—and since ‘being dead / fills her beyond fulfillment,’ Orpheus can no longer be blamed for what happens to her. Although Rilke makes no overt references to his life in ‘Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes,’ the poem seems an attempt to pastoralize his sister’s death. By returning her to the underworld, he has given her exactly what she wants, and since she is now ‘filled with her vast death’, like a fruit ‘suffused with its own mystery and sweetness’, she will not reach up from the open grave to seize him.

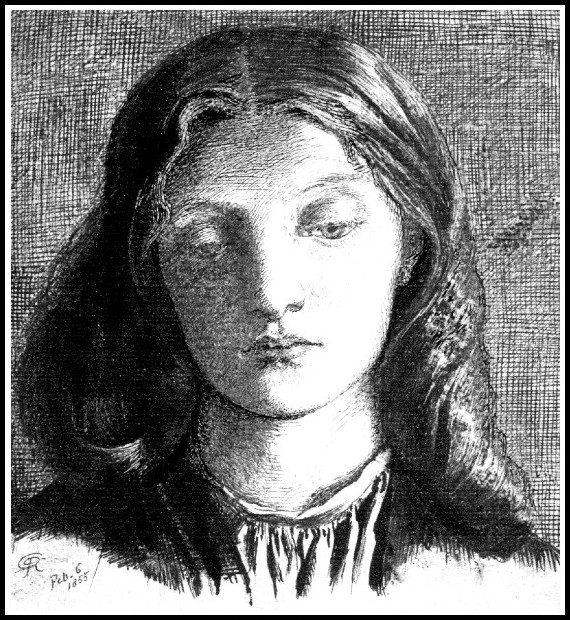

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Elizabeth Siddal, 1855

The poet was also working through issues that emerged in his relationship with his wife, Clara. At the beginning of their marriage, he insisted that they live a secluded life, far from their social circle. When Clara’s friends protested this arrangement, Rilke responded ‘for’ her, by imputing his wish for solitude to her. He used the same argument with Clara herself later, in order to justify living apart from her, and shortly after completing ‘Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes’, he wrote her brother that the two of them had ‘come to an understanding in the very fact that all companionship can consist only in the strengthening of two neighboring solitudes, whereas everything that one is wont to call giving oneself is by nature harmful to companionship’.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Reverie, 1868

Since wanting to live apart from one’s wife is a far cry from engineering her death, it might not be immediately apparent what ‘Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes’ has to do with Rilke’s marriage to Clara. However, the poet doesn’t just claim that Eurydice was fulfilled by death; he also ventriloquizes his horror of relationality through her, just as he did through Clara. She has ‘come into a new virginity / and is now untouchable; her sex has closed / like a young flower at nightfall, and her hands / have grown so unused to marriage that the god’s / infinitely gentle touch of guidance / hurts her, like an undesired kiss’. It was also because of Rilke’s need to establish death as something that happens on the other side of the gender divide that he was unable to remain physically proximate to the women he loved.

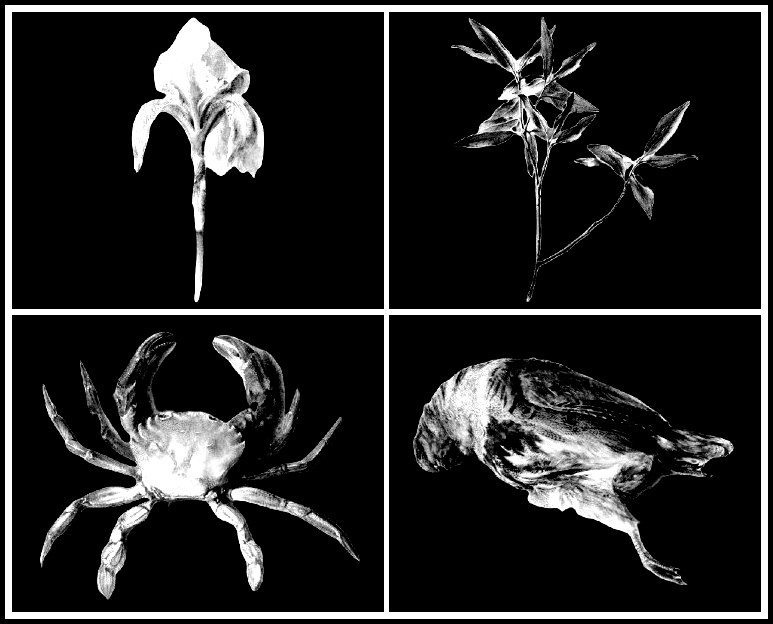

John Ruskin, Fleur-de-Lys, Spray of Olive, Plumage of Partridge, Velvet Crab, 1867-71

KAJA SILVERMAN: THREE BOOKS

Click or tap the image to go to a description of the book

KAJA SILVERMAN

The Three-Personed Picture

KAJA SILVERMAN

Flesh of My Flesh